NO MOVIE DIRECTOR has yet been tempted to make a film of Zola's Ventre de Paris, which is surprising; it is one of the founding legends of Parisian identity and the novel easily passes David Lean's minimum test of twenty good scenes. The dreamlike colours and shades created by Baltard's glass and ironwork pavilions have, nevertheless, been the scene of many works for the cinema, the most memorable perhaps being Marcel EHerbier's haunting wartime film, La Nuitfantastique. After they pulled down the butcher's pavilion in 1973, Marco Ferreri used the heaps of dirt left in le Trou as a setting for his Touchepas lafemme blanche, a film about Custer's last stand. Cameras and crews descended into the controversial "hole," Marcello Mastroianni was given the role of General Custer, while Michel Piccoli, Alain Cuny and Serge Reggiani played the role of the Indians. The film was a great success: Parisians love Westerns—many drive down to the Camargue, near Marseille, to play at cowboys and Indians; the richer ones will spend a season in Wyoming riding the range. The metrostopper fortunately doesn't have to go this far. Just take Line 7 out to Porte de la Villette, where the most extraordinary Parisian cowboy story awaits him.

Where did all that meat, piled so grotesquely high in Les Halles, come from? The slaughterhouses of La Villette. In the nineteenth century the cattle were brought here in droves and the men who slaughtered them were as cruel and tough as any cowhand in the Far West. Their greatest hero had been, before he turned up in their pavilions, "the most celebrated and most shot-at man in the history of Dakota Territory," as his American biographer has put it; in the U.S. press of the 1880s he was known as the "Emperor of the Bad Lands." But he was also a Parisian, an aristocrat of royal lineage at that—and he would end his life as an uncompromising racist. When the Marquis de Morés came back to Paris he dressed up those rough butchers of La Villette in purple shirts and ten-gallon hats: " Morés and Friends" were, for a brief and disquieting moment in French history, a political force that mattered.

When they knocked down the old slaughterhouses in the 1960s President Charles de Gaulle ordered the creation of new ones; they would be the largest, the cleanest and the most efficient abattoirs in the world, the pride of la Grande Nation, something to compare with the passenger liner Le France or the supersonic passenger jet La Concorde. But the project got lost in a jungle of big deals and corruption and, instead, the powers-that-be decided—as they frequently do when confronted with a large hole in an urban space—to create a "cultural centre." Amazingly it works. It is one of the most popular corners of Paris. It was late in June 1896, when news spread through the pavilions that the Marquis de Morés had been killed; he had been felled by a bullet in the side and another in the neck after facing off, with his Colt .45, fifty desert bandits of the Tuareg and Chambaa tribes in southern Algeria. One Sunday, the following July, the Friends of Morés in cowboy outfits marched down from La Villette to the Gare de Lyon, where they were joined by the coach drivers of Grenelle, Paul Déroulède 's League of Patriots, the Napoleonic Imperialist Committee, the Union of Socialist and Revisionist Patriots and a host of other small-time employees and workers of the eastern faubourgs in a procession to Notre Dame Cathedral, draped for the occasion in black cloth. Representatives of the Republican government were also present at the funeral ceremony Beethoven's Sanctus and Fauré 's Piejesu were sung by a large chorus to the accompaniment of the cathedral's grand organ. Then the coffin was carried across the Pont Saint-Martin to the Montmartre Cemetery, where a crowd of over 100,000 had gathered—one of the largest funerals of the nineteenth century Many in the crowd wore the blue carnations of the Royalists; it was the butcher Friends who formed the long guard of honour. "One word sums up this life: Devotion. One word explains this death: the need for Sacrifice," said Édouard Drumont, editor of La Libre Parole. "His love of France, his elan—the highest of French virtues—and his chivalry were the qualities of de Morés, for which we loved him," said Maurice Barrès of the Académie Française. Devotion, sacrifice, élan and chivalry neatly summed up the values espoused by this thirty-eight-year-old Parisian cowboy, gunned down in the Algerian desert.

Just as at Les Halles, it is extraordinary how much of the Marquis de Morés 's nineteenth-century world one can uncover at La Villette. That octagonal stone building to your right, as you emerge from the metro, is where the slaughterhouses' veterinarians used to have their office in the 1890s. The scientific-musical park is scattered with "madnesses" or folies—folies du theatre, folie café, folie du canal, even an éclat defolie. The first you will notice is the folie horloge, an ugly contemporary red iron structure on top of which is a nineteenth-century stone clock: that clock used to chime out the opening and closing hours of Paris's slaughterhouses. In the concrete wall opposite you will find the list of over a hundred butchers mortspour la France in 1914-18; and a long list of those tortured and who died for France under the Nazis. Stop for a while on the Boulevard Macdonald—named after one of Napoleon's generals, not the fast food chain—and look at the line of eating palaces on the opposite side of the street: the beef restaurants were there in de Morés 's day. To the north you can see the périphérique on stilts: the cars rush by today where, in the 1890s, the steam trains for Strasbourg shunted out. Just to the north were the fortifications—and you can get a very good idea of what they looked like in the nearby Fort d'Aubervil-liers. Aubervilliers, beyond thepériph', is another Communist fiefdom, which, like Saint-Denis, Saint-Ouen, Clichy and Courbevoie, houses people from the Third and Fourth Worlds: you lock car doors when you pass through here.

Yet pass through you must. There is something special about neighbouring Aubervilliers which points to the cause of violence in the cowboy slaughterhouses of La Villette a hundred years ago. Between Avenue Victor Hugo and Rue de la Haie-Coq, on the west side of the suburb, are rows and rows of what look like warehouses selling wholesale textiles, clocks, toys, shoes, underwear, jewellery—anything you can think of. They are the solderies of France, an industry which developed in the 1970s and turned this part of Aubervilliers into what may justly be described as the dustbin of the world. The products of virtually every failed industry in Western Europe and beyond, of every unwanted surplus, end up here. The principal dealers, known as soldeurs, buy up these rejected goods—if today it is leather boots, tomorrow it could be computers—at something less than ten per cent of the wholesale price and flog them off to whatever big buyer they can find. The soldeurs never commit themselves to a written contract; all their deals are made by word of mouth and a handshake.

In the 1970s the majority of soldeurs were Jewish immigrants from North Africa; today they are being replaced by the Chinese. As always in Paris, an old historical continuity is working its way through here, in this violent little suburban corner; though the solderies may be a new industry, they did not spring from nothing. This was the site of the Entrepôts Généraux de Paris, which, at the head of the Canal de l'Ourcq, used to buy up as cheaply as they could the factory produce of Paris and the provinces and then sell it off as expensively as they could to the big department stores in the capital. Good fast deals could be made with the neighbouring slaughterers, who began to resent the low prices that the commissionnaires, or middle men, of Aubervilliers paid. Those deals were always struck by word of mouth and a handshake; no contract was ever signed. De Morés became the hero of the meat slaughterers of La Villette by promising to undercut the undercutters, the commissionnaires, the vast majority of whom were Jews.

It was a whole theory, a whole programme, that had evolved out of de Morés 's short but extraordinary life. Nothing had ever been typical about it. He was not even a typical French aristocrat. His Spanish ancestors, knights of the realm, had participated in the conquest of Sardinia in 1322 and, in return for their gallantry, received the Sardinian marquisates of Montemaggiore and Morés. In the 1820s de Morés 's grandfather had participated in a failed Sardinian coup d'etat and lost all his properties, so he left for France, where he married a descendant of the first French Bourbon king, Henri IV Their son made another brilliant marriage, with a family that had conquered Algeria for France, and it was from this noble union that there was born, on 14 June 1858 in the exclusive faubourg de Saint-Germain, the boy who could claim to have royalty in his blood in addition to a very long name: Antoine Amedee Marie Vincent Manca de Villombrosa, the Marquis de Morés et de Mon-temaggiore. His friends called him Antoine. A childhood photograph shows him with a gun in his hand.

A turbulent child, his parents entrusted him to one of the toughest tutors of the French Riviera, where they had taken up residence in the 1860s. The Abbé Raquin had Antoine speaking English, German and Italian before he was ten, and infused him at the same time with a love of the main tenets of Catholic Christianity. At the College Stanislas in Cannes he defended the weak and was the terror of the strong, over whom he towered. He graduated from the officer training school of Saint-Cyr when twenty-one—a handsome man of six foot with curly black hair, dark eyes and slightly hooded, Asiatic eyes. He already wore what would be his signature in the Far West and the pavilions of La Villette, a black moustache with upward turning, needle-point waxed tips.

Saint-Cyr's class of 1879 included Philippe Petain, the future hero of Verdun, the future anti-hero of Nazi-occupied France—but at the time too poor to be the Marquis' intimate friend. That friend was Charles de Foucauld, a bit of a dandy at the time. It was not an image that stuck. De Foucauld would become one of France's uncanonized saints, a master theologian, who took his vows as a Trappist monk in Syria in 1891 to become "the hermit of the Sahara"; for twenty years he lived among the Bedouin Arabs of southern Morocco, who murdered him in 1917. One may justly speculate as to whether or not there was some element in de Morés 's complex personality—which led him to the same terrible end as his friend—that, in different circumstances, would have taken him along a similarly devout route. "You know me, you know my affection for you," wrote de Foucauld to de Morés the day before he made his vows. "Poor monk, I pray from afar for all those I love. I ptay for you." After the years at Saint-Cyr de Morés, like his Christian friend, he would on many an occasion face the sun and his God alone.

Life in the barracks of the French Army, following its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, was anything but an adventure. To satisfy the ancient cravings for honour and chivalry aristocratic officers used to resort to hunting with horses and duelling with swords. It was not enough for an elegant, royal marquis. Having slain two men with his sabre, de Morés resigned his commission in 1881 and turned his talents to the world of high finance.

Many of the big capitalists of the nineteenth century were men of blue blood; the door that opened on these two worlds was marriage. De Morés 's eye fell on a small German-American lady with a huge fortune, Medora von Hoffmann, whom he married in the Church of the Stained Glass Windows, Notre Dame de l'Espérance, in Cannes in February 1882. After a few idyllic months in Provence, the young couple took a steamer for New York and the banking enterprise of Louis von Hoffmann, de Morés 's new father-in-law. Von Hoffmann had built up an empire of international trading, buying and selling currencies and securities in the foreign exchanges at the right time; he pioneered the system of arbitrage, as it came to be known. For de Morés it provided a practical lesson on how wealth could be generated from narrow margins on a large capital base—watch those margins and cut out the waste. It would become a moral imperative for this Catholic French businessman: "My birth confers no privileges on me," he used to repeat; "it gives me great responsibilities." Cutting the waste was soon translated into a battle to rid the market of the army of middlemen de Morés saw growing around him—rich bourgeois parasites who added nothing to the production process save their commissions and obstruction of trading forces. De Morés spent the rest of his life attempting to put the poor, honest producer directly in contact with the poor, honest consumer: it was the economics of Billy the Kid.

This is a point worth emphasizing. De Morés 's initial struggle in business was with the middleman. Nothing in his behaviour or in the many interviews he granted in America gave a hint of the rabid anti-Semitism he later came to espouse. De Morés 's particular interest in the cattle business began when he met Commander Henry Gorringe, a land promoter, who had brought one of Cleopatra's needles to New York during his service in the U.S. Navy. After passing through the Bad Lands of Dakota Territory one summer Gorringe had set up the Little Missouri Land and Cattle Company with a tough local Scotsman, Gregor Lang, settling a small herd of cattle on a plot of land to prove his ownership. De Morés bought an option in Gorringe's property. Little did he know that the only property to which Gorringe's title laid claim was a set of cantonment buildings the U.S. Army had used during the Indian wars. Nor did he know that Gregor Lang was a spokesman for commercial hunters of buffalo, bear and deer—the natural enemies of cattle herdsmen.

In March 1883, de Morés set out in one of the Northern Pacific Railway's 4-4-0 steam express trains for Dakota. As soon as he discovered the fraudulent nature of the title, he informed Gorringe's agents that he was not going to exercise his option and, instead, founded a new town on the far side of the Little Missouri, naming it after his wife, Medora. Through the U.S. government he purchased around 4,000 acres of land and within a month he was building a huge brick slaughterhouse, corrals for the cattle, a railway spur that connected to the Northern Pacific and, high on a riverside bluff, a wooden chateau for himself and his wife. In May 1883 he registered the Northern Pacific Refrigerator Car Company in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and then committed the unforgivable sin of fencing in his land. With his refrigerator cars, de Morés aimed at cutting out the middlemen: "From the ranch to the table" was the Frenchman's appealing slogan.

There is evidence of a link between the commercial buffalo hunters of Little Missouri and the middlemen in New York, who took exception to the red painted storefronts of de Morés 's new meat shops in the city. The shops were organized as cooperatives, whose stockholders were to be the common people of New York. De Morés, thanks in large measure to his father-in-law, had mustered considerable support, including that of New York's mayor W R. Grace, New York bankers such as Eugene Kelly, and the famous labour economist Henry George. All of them were seduced by the Frenchman's message: cut out those parasitic middlemen.

But trouble developed in the Bad Lands. Gregor Lang's son, Lincoln, spoke up for the hunters' "inalienable rights" to roam the territory—without barbed-wire fences. Frank O'Donnell, a hunter, told the elder Lang he would shoot de Morés on sight. Less than one year after the gunfight of OK Corral in Tombstone, Arizona, the gunplay began on the banks of the Little Missouri. Nearly every night shooting broke out at the chateau. O'Donnell had organized a gang of vigilantes; in the daytime they shot up the town. The Marquis called in a sheriff's posse from Médan, 130 miles away. The O'Donnell gang disarmed them as they stepped off the train. But the outlaws did not know that Morés and friends, equipped with lever-action Winchester rifles, were waiting for them in the gully. In the gunfight that followed, one of O'Donnell's men was killed: "His horse was shot from under him, and it was really a sight to see him fight. He was very nervy," reported de Morés to the New York press. O'Donnell and another man were taken into custody. De Morés was indicted three times for murder, but on each occasion the charges were dismissed, despite the howling mob of buffalo hunters in the courts as well as outside his log-house gaol.

But the meat-packers of Chicago and New York—Armour, Swift, Hammond, Nelson Morris and Schwarzchild & Sulzberger—were associated in a price-fixing trust that was getting its support from a very bitter Commander Henry Gorringe in New York and his men on the ground in Little Missouri, the "Lang crowd" as they were known. They organized a nationalist press campaign. In the American Nonconformist of Tabor, Iowa, a columnist wrote: "Counts, marquises, dukes and any other foreign aristocrats shall not establish ranches in Dakota or in any other part of this country The soil of America belongs to American citizens only" De Morés was finished; he and von Hoffmann lost several million dollars in their Dakota enterprise.

Back in France, de Morés was quoted as saying in 1886, "I am twenty-eight years old. I am strong as a horse. I want to play a real part. I am ready to start again." He left for Indochina in pursuit of a railway scheme designed, once more, to cut out the predatory middlemen.

De Morés wanted to build his rail as a link between the landlocked Chinese province of Yunnan and the Gulf of Tonkin, thereby destroying a trade that had for the last thirty years been controlled by the Black Flag Pirates. The Pirates manipulated the local governments of Tonkin, as North Vietnam was then known, and terrorized the population. They came from southern China, which they had poached for decades. And they were the main enemy of the French Army, which viewed itself as a liberation force that had lost, since the 1870s, thirty thousand men in the borderland jungles of Tonkin and China. Vicious debate over these losses in 1885 had brought down the last government of Jules Ferry, a Moderate Republican and educational reformer, whom the metrostopper in Paris will recognize because so many streets and schools are named after him. The elections of that year brought in a number of Royalists, whose avowed purpose was to destroy the Republic, and also a number of deputies of the extreme left, who called themselves new men. They were nothing of the kind; they were the old men of the barricades, many of whom had returned from exile following the suppression of the Commune of 1871. As the Marquis de Morés prepared the next stage in his business career, the French Republic moved in the direction of the two extremes, left and right.

There was still nothing in de Morés 's language to suggest he was a racist, though his experience in the Bad Lands had certainly increased his passionate aristocratic sense of mission for France. He had learnt directly of the terrible conditions in Tonkin when returning to France from a tiger hunt in India on a French ship that happened to be transporting several of his old classmates from Saint-Cyr back home from service in Indochina. The scheme to build a railway from Lang Son, on the Chinese border, to the Gulf of Tonkin was born at that moment, in spring 1888. By summer he had gathered enough capital to fund the project, which he presented to the new Radical government in Paris in August. "I don't share your political views," he told the Foreign Minister, "but politics stop at the frontier. Therefore, you can use me or not." The Foreign Minister was convinced of his use and gave him the go-ahead— but not without fierce opposition from a certain Ernest Con-stans, then an obscure Under-Secretary of the Navy, who had, however, been for six months Governor General of French Indochina.

In December 1888 de Morés was in Haiphong to discuss his project with the new Governor General, Etienne Richaud. Richaud was attracted to this polite but ruthless marquis who had stood up to the outlaws of the Far West; Richaud revealed what a scoundrel his predecessor, Constans, had been—huge sums of government money had been diverted to his private use while he had left the administration in chaos. De Morés set off on his long march north to Lang Son satisfied that he had found a very useful ally. Day and night he and his column of coolies trudged by foot through a tepid jungle drizzle until they eventually arrived at the Chinese border where de Morés was astonished to discover how eager the Chinese were to trade with them. He noted in his diary: "The colonization of Tonkin will not be accomplished with rifles, but with public works. We must take the position of being associates of the people of Tonkin." It was the same old economic philosophy again of building direct links between producers and consumers through an efficient transportation system, and cutting out those piratical middlemen.

From Lang Son, de Morés 's columns set out south along what is now Route 4 in North Vietnam. They crossed a heavily wooded country, peppered with emerald pools, climbed the mountain pass of Deo Co and then descended into a stifling valley where the villages lay devastated—the Black Flag Pirates had just passed through. On n January 1889, after four days of marching across 120 miles of jungle, they entered Tien Yen on the Gulf of Tonkin. With Richaud's authorization, de Morés immediately began work on docks for this sea port. But events in Paris caught up with him.

One of the last acts of the Ferry government had been to revise the voting system so that a single candidate could run for several constituencies. Ferry's purpose had been to encourage the development of parliamentary parties—which did not yet exist in France. But he had not counted on the rising popularity of General Georges Boulanger, a new Napoleon on horseback, who ran for all political extremes and in constituencies stretching across the country. In the provinces he was supported by the Royalists. In Paris he had the support of the old revolutionaries and Communards—where he won with a landslide. France was on the point of being taken over by a Boulanger dictatorship when, through a dainty piece of parliamentary manoeuvring, a new Republican government was established—with its new Minister of the Interior, Ernest Constans. Constans had no qualms about legality. He threw many of Boulanger's supporters in gaol. In April 1889 Boulanger, realizing he was next on the list, fled to Brussels, where, in 1891, he shot himself on his mistress's grave.

De Morés was back in Paris in March 1889, for what reason one cannot be sure. It seems that the government had tempted him back with the promise of a grant; he also appears to have been attracted by the virile new politics of the Boulangist cause. At any rate, he immediately launched an attack on Constans for his corruption in Indochina, using Richaud's dossier as evidence. Richaud was ordered back to France. But he never got there: the Governor General and his cabin boy were found dead in their cabin and were buried at sea.

De Morés 's denunciations of the Minister of the Interior ended when he drew a gun on Constans's gang of thugs during a by-election in Toulouse. De Morés thought it a good time to withdraw for a few months in England, where he read Édouard Drumont's popular book La France juive. He suddenly saw the light, the reason for all his losses: his meat cooperatives in New York had been scuttled by Jewish butchers; the Tonkin project had been blocked by a Jewish engineer to whom he had refused to pay a commission; the Toulouse campaign had turned into a farce because the department prefect was a Jew. He returned to Paris in the New Year, 1890, and arranged a meeting with this Édouard Drumont, editor-in-chief of La Libre Parole. Drumont invited him to a political rally in Neuilly for a Boulangist deputy who had gained a following with the slogan: "War on the Jews!"

France was entering a new age of vehement protest, and de Morés found himself at the head of it. At Neuilly the Marquis, dressed in a dark suit and a gardenia in his buttonhole, was the star of the show. The rally was held in a popular dance hall. Disgruntled workers, shopkeepers and small-time merchants drawn from the outskirts of Paris—along with the proud butchers of La Villette—provided the applause and the cheers. But there were also the elegant of Tout Paris: Prince Poniatowski, the Prince de Tarente, the Comte de Dion, the Marquis de Breteuil, the Marquis de Peyronnet and the Due d'Uzès. "The rich, the aristocrats, are ready for all the necessary sacrifices," intoned the Marquis de Morés. 'As for myself, I am ready to sacrifice my life in the struggle against the financial feudalism that is supported by the government forces." It was a call for revolution.

In Paris's municipal elections that spring he ran for the down-and-out district of Les Épinettes, in the Seventeenth, with Gaston Vallée, a locksmith from La Villette. "I am above all a socialist," he told the electors; he attacked the middlemen, the bourgeois parasites. "The producer should have the maximum possible return for his work," he said; his revolution was against the accapareurs, the monopolists—the Jews.

De Morés lost the election to a former Communard. His next campaign was to gather support for his "socialist" cause at the "Festival of Labour" on i May. "I invite you all," he told his disappointed supporters at Les Épinettes, "to come and lunch with me on the Champ de Mars. Each of you will receive a cudgel, and at the end of this cudgel there will be a basket containing a loaf, a sausage, a litre of wine and a whistle." The cudgel and whistle were enough for Constans to have de Morés arrested on the charge of "provocation of crowds, provocation of murder, pillage, fire." The Marquis spent the next three months in gaol. De Morés was getting a lot of coverage in both the French and the American press, which continued to be fascinated by the "French cowboy" When he got out of prison he turned to his old skills as a duellist. The Jewish reporter Camille Dreyfus—no relation of Alfred Dreyfus of the famous affair—met with the Marquis in the Belgian town of Corn-mines with pistols at dawn. Dreyfus received a bullet in the elbow. He was lucky. In France's Gay Nineties you did not sue an opponent for libel in the press; you killed him. De Morés 's cool and elegant manner of dispatching an enemy engrossed newspaper readers in Paris and New York. Some of the Jews who were challenged by de Morés refused to be provoked, like the great Joseph Reinach of La République Française. But Captain Armand Mayer taught fencing at the École Polytechnique. He seconded Captain Crémieu-Foa in a set piece of swashbuckling with Drumont, who was seconded by de Morés. A wretched little squabble at the end of the duel led to the seconds challenging each other with "ordinary swords of combat." A duel was arranged in a covered arena on the Îie de la Grande Jatte at 10 a.m., 23 June 1892. Mayer came charging in, flailing his weapon in every direction. The Marquis, a white glove concealing his mighty right wrist, simply held his sword out: it pierced Mayer in his armpit, ran through the upper part of a lung and came to a halt on his spinal column. Mayer dropped his sword and said, astonished, "I am hit." He calmly walked over to the seconds, the wound under his arm barely bleeding. De Morés seemed equally astonished. He came over to the wounded man and politely asked, "Captain Mayer, will you let me shake your hand?" They shook hands and Mayer promptly collapsed, never to regain consciousness.

Mayer's death did the anti-Semitic cause in Paris no good. As far as the Marquis was concerned, it ended all chances of him being elected to office. That only made the Boulangists more violent. Yet, somehow, the Marquis de Morés seemed more enchanting than ever. In his memoirs, Marie-Francois Goron, Chef de Surete, has left a record of the Marquis' arrest following Mayer's death. The Marquis was found in a hiding place on Boulevard Pereire. "Great heavens, Monsieur, you have come to arrest me? And you bring no police?" "I come without ceremony," Goron replied. "I am alone with my secretary." They descended the staircase together. De Morés comforted the despairing concierges "with the airs of a prince and caresses in his baritone voice." They mounted Goron's open carriage and "off we went, chatting away, as if we had just had dinner together at the cabaret."

After six weeks in prison the Marquis was acquitted of all charges. He turned to the butchers of La Villette for help. Gaston Vallée had established the first contacts. The butchers loved the cowboy stories and admired the man's physical stamina. There was ample material here for an anti-Semite to exploit: the Jews of Aubervilliers would buy up the cattle of La Villette for a pittance; they were the detested middlemen who earned their commissions at the honest producers' expense. In the spring of 1891 de Morés 's political office on Rue Sainte-Anne—just across the road from the old Bibliothéque Nationale—was tipped off that Jews were selhng unhealthy meat to the brave French soldiers guarding the fort of Verdun. De Morés and Jules Guèrin, the most blackhearted anti-Semite in town, disguised themselves as cattle merchants and, in the early hours of the morning, headed off for La Villette. Out of the 3,200 cattle marketed that day, around forty head had been separated for health reasons. They were purchased, noted the investigators, by Messieurs Wormser and Salomon. De Morés, in the company of two butchers, followed the sick beasts out to the Porte de Pantin, where they were loaded onto a train bound for Verdun. De Morés boarded a very fast stagecoach and, so he claimed, managed to watch the same train come into Verdun, where the beasts were taken by wagon to the city's slaughter-houses; two of the beasts collapsed before they arrived there. When the Journal des Debats reproduced the de Morés report, the Ministry of War ordered the establishment of a new military slaughterhouse at Verdun. De Morés was now the hero of the butchers of La Villette, a much needed battalion for his cause: he dressed them in cowboy clothes and called them " Morés and Friends."

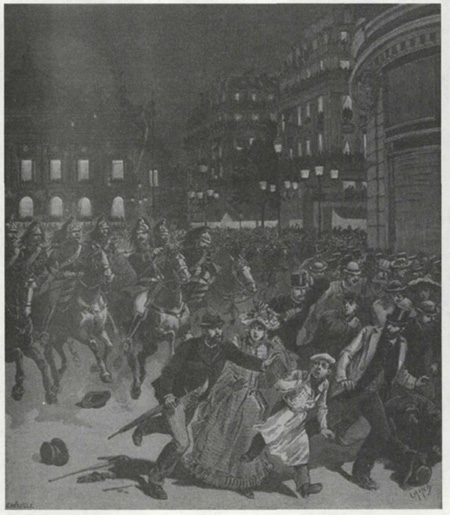

In the winter and spring of 1892-93, no Jew could sleep tranquilly when Morés and Friends were in the neighbourhood. No political enemy of the Marquis could hold a political meeting in town without it ending in a brawl. De Morés had brought the terror of the Far West to Paris. But it all came to a sudden end when the Marquis took on a man who proved his match: Georges Clemenceau, leader of the Radicals, the Tiger of France.

Clemenceau had been, perhaps unjustly, implicated in the biggest financial scandal of the century, the bribing of politicians and other public officials by the Panama Canal Company, which would face a spectacular bankruptcy before as much as a dozen miles had been dug across the mosquito-infested American isthmus. There is some evidence that Clemenceau was receiving money through Gustave Eiffel, the man who built the tower; but this was unknown at the time. At any rate, Paul Déroulède, a Boulangist deputy, possessed no evidence at all when he denounced Clemenceau as head of the circle of bribery and corruption within the Chamber. "There is only one response to be made," replied Clemenceau: "Monsieur Paul Déroulède, you have lied!" The two men fought it out with pistols on the Saint-Ouen racecourse before three hundred spectators. The only damage done was the spoiling of both men's political reputations. Morés and Friends went on the rampage over the next months, screaming insults at Clemenceau and hallowing the name of Déroulède. Clemenceau took the Marquis to court for libel and won after proving that it was he, the Marquis, who had been paid off by the canal company, not Clemenceau.

That August, 1893, Clemenceau attempted to renew his parliamentary seat for the department of the Var. Morés and Friends descended in hordes to disrupt the political meetings. They managed to oust Clemenceau from office, but only temporarily; they did irreparable damage to their own political reputations. The Tiger returned to public life as the defender of Captain Alfred Dreyfus in 1898 —anti-Semitism remained alive and well in French public life for several years to come. But Morés and Friends had long disappeared from sight and sound.

In late 1893 the Marquis left France in pursuit of a mad project designed to divide the British Empire in two. The plan was to incite the tribes of southern Algeria to march on Ghadames and Ghat, where they were to join the Mahdi on the Upper Nile and drive the British out of Sudan. The result was the opposite: the Algerian tribes turned on him. The Marquis died alone on 9 June 1896, after a long and bloody gunfight, under a cactus at El Ouatia. "Remember," he wrote in his last letter to his son, Louis, "in striving, against every obstacle, for justice and truth, you bring yourself nearer to God."

As you walk around the Cité des Sciences and the Cité de la Musique, you will notice the graffiti crying out for God and justice where others have scrawled the signs of racial hatred. It is remarkable how much remains of the old district of La Villette.