MÉTRO STOP NO. II, Saint-Paul, is the only station to serve the seventeenth-century quarter of the Marais, the most popular stalking ground in town. Jules Michelet, who was born here in 1798, loved it: its dark alleys and stove-bellied, pale yellow stone walls coloured his whole account of the French Révolution. Walking in some of its streets today you can still pick up something of the atmosphere he evoked. The station stands on the site where, in the early morning of 10 August 1792, crowds of armed artisans—"from the Bastille up to the church of Saint-Paul in this wide and open part of the Rue Saint-Antoine"—converged to the beat of drums and the tocsin bell of the Section Quatre-Vingts; onwards they marched to the Tuileries Palace, where, in a pitched battle, they overthrew the Bourbon monarchy The high ornate Jesuit façade of the Église Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis, on the south side of the street, towered over them—a reminder that, before the crowds in Paris were atheist revolutionaries, they were Catholics of the most radical, fervent kind.

The Jesuits had been introduced into the Marais by the widow of the Constable of France, killed in battle in November 1569 defending Catholic Paris against the Protestant warriors who surrounded the city At the time there seemed nothing inconsistent about inviting the Jesuits into Paris; indeed Ignatius Loyola, with Francois Xavier and three Spanish priests, had founded the Society of Jesus in the crypt of the Sanctum Martyrium near the summit of Montmartre in 1534. No city in France was more Catholic than Paris in the sixteenth century.

There exist a few remnants of that late Renaissance Catholic Paris in the area around here. To the west of Saint-Paul, on a black-and-white Louis Philippe wooden facade, is a sign, "The Auld Alliance, Scottish Pub," and it sells the best Scottish beers and the largest selection of whiskies in Paris, including the Dallas Dhu. On the walls hang old maps of Scotland and several historical documents, going back to the Treaty of Corbeil of 1326 between the King of France and Robert, by the Grace of God, King of the Scots. The documents prove, as the singing in the pub still demonstrates, that the ties between Scotland and France run deep— deep and religious.

The singing leads back to a sixteenth-century ballad about a soldier called Montgomery. It is one of the saddest ballads I

know.

Moy très bien les congonois

Qui naguères estois

De Montgommery comte.

Montgomery's ancestors were counts, starts the song in old French. In fact Gabriel de Montgomery's ancestors can be traced to Norman retainers of William the Bastard, who followed the Duke to England after the Battle of Hastings in 1066. The older branch established themselves as seigneurs in Normandy, while the younger branch had to carve out their fortune as warlords in Scotland, attachéd to King David I (1124-53). ft w a s poor Scottish lords like the Montgomeries who furnished the spearhead of the French royal armies that would eventually throw the English out of France. In recognition of their service Charles VII created the Hundred Archers of the Scottish Guard in 1422; a little over a century later, in 1543, Francis I promoted Gabriel's father, Jacques, to be their captain. It was one of the most powerful positions in the kingdom and was the reason why the Montgomeries, as the song goes, became counts.

Gabriel, born on the family properties in Normandy or in the Beauce, either in 1526 or in 1530, was groomed to be a count.

But fate decided otherwise.

La France m'a cogneu,

Chevalier bien reçeu

Monté en fort bon ordre.

As Lieutenant of the Scottish Archers the young Montgomery cut a dashing figure in court. Then, on a sweltering Friday, in

the "wide and open part" of the Rue Saint-Antoine—not far from where the métro stop now stands—King Henri II of France challenged

Gabriel de Montgomery to a joust. What occurred next was one of the most tragic riding accidents in history; the whole of

Western Europe would be plunged into a generation of religious war and strife as a result of it.

Par un fatal destin

Le Roy voulant s'ébattre

Me dist par un matin

Qu'à moi voulait combattre.

Not even the most talented playwright could pull together all the strands that fatal destiny suddenly combined on that day. Europe was at a turning point. The religious wars in what we today call Germany were over, the old Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, sworn enemy of France, had abdicated. In April 1559 Spanish and French envoys had met in Cateau-Cambrésis, on the French border with the Spanish Netherlands, to sign a treaty which ended sixty years of war in Italy. The great dynastic tensions that had dominated the first half of the century ended at Cateau-Cambrésis. The year 1559 should have ushered in peace for all of Western Europe, were it not for Montgomery's jousting lance.

Two royal marriages had been negotiated at Cateau to seal the treaty Philip II, a widower since the death of Mary Tudor, Queen of England, the previous November, was to marry Henri IPs eldest daughter, Elisabeth; and the French king's thirty-six-year-old spinster sister, Marguerite, was to marry Philip's ally, Emmanuel-Philibert, Duke of Savoy Henri II arranged a fabulous show in Paris, where the two marriages were to be celebrated in late June, the central event being a five-day jousting tournament held on the "wide and open part" of Rue Saint-Antoine, at that time the only open space in Paris, a favourite spot forpromeneurs that stretched from what is now Rue de Sévigné to the Bastille and northwards up to today's Place des Vosges, which was then occupied by the royal Château des Tournelles. Stands higher than many of the houses were built around the periphery of the space, decorated in the colours of France, Spain and Savoy; the paving stones were torn up and replaced by sand; and the open city sewer—today Rue de Turenne—was hidden from sight by a huge wooden cross. Elisabeth married Philip II, who had sent the haughty Duke of Alba as his proxy, on Thursday, 22 June, and on Wednesday, 28 June, the jousting began. The weather got hot and sultry.

The heat had made the crowds uncomfortable and nervous on Friday afternoon—not morning as in the ballad—when King Henri was

due to joust. At the centre of the royal box, dressed in bejewelled garments, sat his queen, Catherine de Medici; to her right

was her eldest son, the future Francis II, with his recent wife, a tall lanky adolescent, Mary, Queen of Scots. Queen Catherine

had passed a difficult night in the Château des Tournelles; she had dreamt of her husband lying on the ground in agony, his

face covered in blood. Medieval superstition, magic and prophecy was never far from the surface in this late Renaissance world.

The accumulating signs of the approaching catastrophe had a Shakespearean tone: Nostradamus, the King's seer, had written

in 1555 in quatrain XXXV of his Centuries that

The young lion will surmount the old

In battle field in single duel,

In a golden cage, his eyes shall be holed,

Two wounds in one, then a death most cruel.

The stars foretold a violent death by iron or by fire at the age of forty— Henri II was in his fortieth year; Bishop Luc Gauric, famous in Italy for his accurate predictions, had warned Henri to avoid all combat at the age of forty because he could suffer a wound in his head that might render him blind. It was the Habsburg emperor, Charles V, who had told Admiral de Coligny that the young Gabriel de Montgomery, to whom he had just been introduced, had a mark between his eyes that signified the death of a prince of the fleurdelis. Catherine, like her husband, was aware of all these tales, and would rather have been with the King on the banks of the Loire.

But not King Henri, who carried the black-and-white colours of his mistress from Anet, Diane de Poitiers, when he rode out on to the field of contest. "Squeeze tight at your knees!" he shouted out at his first challenger, his future brother-in-law, Emmanuel-Philibert, "For I shall give you a good shaking, whatever our alliance and fraternity!" Henri wanted to show who was King. The two chargers raced towards each other, there was a crash, Emmanuel-Philibert tottered awhile — but remained in his saddle. Then it was the turn of Francois, Due de Guise, one of the most powerful men in the kingdom. The chargers sped across the sanded course; another shock: neither man showed a sign of trembling. Henri was bitterly disappointed in his own performance. Against whom could he prove his royal virility?

His eye alighted on the Lieutenant of the Scottish Archers, blond, athletic and ten years his junior. Trumpets and bugles brayed and they charged; the sound of the collision echoed around the square—but both men held fast to their mounts. By the rules of the game, the King's jousting for that day should have ended there. But his Valois blood was up. He demanded his challenger to play again. Montgomery refused, invoking the heat and the late hour of the day. "It is an order!" shouted the King. Queen Catherine sent a messenger begging him to stop. The Chief Marshal was called in to place the golden-coloured helmet on the King's head; as he lowered the visor, the Marshal said, "Sire, I swear by living God that for the last three days I have been dreaming that something terrible will happen to you, that this last day will be for you Fatal."

Montgomery prepared himself. For some inexplicable reason his team forgot to replace his lance, as the rules required; he went into the field with the lance that had been cracked by the last rude encounter. As the King entered the course one report writes of a young boy running out screaming, "Sire, don't go!" The trumpets, strangely, did not play. Instead, there was a hush. A rumour spread like a menacing wave through the crowd. The horsemen faced each other, then set off at a gallop; there was a loud report as Montgomery's shaft shattered.

The King swayed to left and right. Grabbing his horse's neck he managed to hold himself in his saddle. He slumped forward. The Queen, at her tribune, stood up; the crowd gasped. The Constable of France, Montmorency and Marshal de Tavannes rushed out and allowed their sovereign to slip into their arms. On the ground, they carefully removed the helmet; blood poured into the sand.

What happened next is the subject of 450 years of debate. Some witnesses claim to have seen Montgomery beat a way through the throng that had gathered around the prostrate King and, beside himself with grief, ask for a pardon—which the King granted. Other contemporaries claim the King was already unconscious, which seems likely. What probably happened is that Montgomery was among the men who carried the King to the Château des Tournelles. At the entrance, despite the splinter in his right eye emerging from his temple, the King had regained consciousness sufficiently to mount the steps himself, with aid. Montgomery was at his bedside that evening and it was perhaps there that the King said to him: "Do not concern yourself, you have no need of a pardon. You obeyed your King and acted as a good knight and valiant man of arms."

For a sixteenth-century chevalier like Montgomery that verbal acquittal was the equivalent of the voice of God. But the tension in the court, particularly in the vindictive sobbing of the women, was unbearable. Catherine de Medici never would forgive him—he was a regicide, an outcast. Montgomery fled Paris that night. The King died in agony on 9 July.

A strong monarch like Henri may have held the kingdom together, though it would have been a repressive age for the Protestants because Henri had never been tolerant of the reformed faith. Catherine de Medici, on the other hand, though the niece of a pope, as Queen Dowager initially showed a surprising degree of indulgence. But the ultra-Catholic family, the Guises, managed to seize control of the government. Protestant circles spoke of a coup d'état. Their leaders, in February 1561, met at the port of Hugues, near Nantes, to discuss what to do. They decided that the best course of action was to capture the main members of the royal family and set up a regency in their favour. The plan went seriously wrong and fifty-two of the ringleaders, singing psalms as they queued up for the block, were beheaded in front of the royal family at Amboise in March. For France it was the beginning of civil war. In fanatical Catholic Paris it gave rise to a new derisive term for these treasonous heretics: the conspirators of Hugues became the "Huguenots"—a name soon applied to all Protestants in France.

The regicide Montgomery had been on the run. First he had fled to his estate at Ducey in Lower Normandy, by the Baie de Saint-Michel. Obviously he was not safe there, so he set sail for that haven of liberty and latter-day adulterers, the island of Jersey, recently annexed to the diocese of Winchester, though there was nothing very English about the place in those days—its inhabitants spoke a Norman dialect that made Montgomery feel at home. Diplomatic correspondence proves he was in Venice in December 1559. By the following spring he was in London at the court of Queen Elizabeth I.

There he acquired a fine command of English; befriended Sir William Cecil, the brilliant humanist and now the Queen's Secretary of State; established an excellent rapport with Sir Nicholas Throckmorton, shortly to be named ambassador to the Valois court; and earned the respect of the Queen herself. He also converted to the reformed religion, though exactly how this happened is not known. Montgomery became a Calvinist, the radical branch of Protestantism which was hardly in the spirit of Cranmer's Book of Common Prayer that guided Elizabeth's resplendent court. But it was the strain that was spreading fast through his native lands of Lower Normandy Most likely, what prompted the conversion was an appeal he received in November 1561 from François de Bricqueville, Baron de Colombières, "to come to the assistance of the Protestants [les réformés] of Lower Normandy, who are persecuted and envisage taking up arms."

Montgomery landed in Lower Normandy in December 1561 and began his career as a liberator of the Protestants; his new seigniorial arms were proudly emblazoned with a helmet pierced by a lance. Montgomery seized Avranches, in Lower Normandy, killed all the local nuns and priests and shipped the cathedral's gold and silver off to the island of Tombelaine, by Mont-Saint-Michel. He then marched his little army into the Loire Country, up the course of the river, to the cathedral town of Bourges, which he took without a fight. By late spring of 1562, the Huguenot armies—the soldiers dressed in white surcoats and chanting psalms as they went into battle—controlled the Loire, Saintonge, Poitou, Lyon, Dauphiné and the valley of the Rhône. But in June and July plague broke out in the towns and the Due de Guise's Catholic armies began to make progress. Montgomery conducted a brave defence of the Norman city, Rouen; Queen Catherine, knowing this, participated in the battle. The city was taken, the inhabitants slaughtered—but Montgomery made his escape by boat down the river.

An English fleet arrived in Le Havre on 29 October subjecting the town to such a vigorous occupation under the Earl of Warwick—many inhabitants were forced to leave their homes, Frenchmen were excluded from government, the English pound sterling was the only acceptable currency—that even the Protestants were shocked. At Amboise, in March 1563, a peace between Protestants and Catholics was patched together and they joined forces to throw the English out of Le Havre on 30 June.

Protestantism in France was still winning hordes of converts, many through contact with the Spanish Netherlands. In August 1567 Antwerp rose in rebellion, and from there the violence spread through the country, spilling over into France. In the Netherlands, King Philip II, not a tolerant Christian, used the vilest means of repression. In France, religious civil war broke out once more. Montgomery participated in the siege of Paris at which Montmorency, the Constable of France, was killed. Another peace was cobbled together at Longjumeau in March 1568, but as Throckmorton noted gloomily in a dispatch to Queen Elizabeth later that year, "there are more Protestants who have perished during this peace than during the preceding war."

There began, in the summer of 1568, a huge exodus of Protestants from all parts of the country to the fortified port town of La Rochelle, on the Atlantic coast. It was known at the time as the "Flight from Egypt." The fulcrum of French Huguenot power in France thus shifted south-west. The Protestant spirit was further galvanized by the arrival ar La Rochelle on 28 September of Jeanne d'Albret. Her mother had been the elder sister of Francis I; her late husband, Antoine de Bourbon, was head of the Bourbon family, direct descendants of Louis XI, and thus heirs to the French throne should Catherine's unhealthy Valois children have no issue. Jeanne was Queen of the small Protestant kingdom of Navarre, in the Pyrenees, which was at that moment overrun by Catholic forces. She was accompanied by her fifteen-year-old son, Henri—the future Henri IV Every Huguenot saw in this athletic figure their true sovereign, while his widowed mother acted as an excellent counter to the black-gowned Catholic dowager queen, Catherine.

Catherine de Medici was becoming increasingly intolerant of heretics. In April 1569 the Spanish ambassador came to her chamber after learning that she had fallen ill. He told her that the time had come for la sonoria, the "death knell." This delightful image of la sonoria— annihilating all her main Protestant opponents with one ring of the bell—brought new life to the Queen Mother; she was soon on her feet again. The ambassador's sweet words of mass murder also encouraged her already pronounced tendency for the occult, her irrational "medievalism" one could justly call it. Catherine collaborated with an Italian sorcerer who kept his shop, Vallée de Misere, on the Quai de la Megisserie in Paris. His spells seemed to work particularly well when poison was added to the menu. Several Protestant leaders died of spasms in the month of May 1569. On 11 June Prince Wolfgang of Bavaria, who was bringing across France an army of German Reiters and lansquenets to the aid of the Huguenots, dropped dead after quaffing a goblet of wine.

That was the month Jeanne d'Albret summoned the saviour of the Protestants, Gabriel de Montgomery, to La Rochelle. She named him Lieutenant General of the Kingdom of Navarre and ordered him to bring her subjects back "under the obedience of Her Majesty [herself] and punish the rebels, who had revolted and pillaged the reformed churches and imprisoned their ministers." It was the sort of job for which the merciless Montgomery was ideally suited.

Montgomery, dressed entirely in black with a glacial look in his mournful blue eyes, led an army into the little kingdom of Navarre, covering over 150 leagues in ten days. By August he had restored the lands to their Protestant sovereigns. It had been a brutal campaign. Montgomery's handling of the Carmelite monastery at Trie was typical: all the monks were slaughtered and their bodies chucked into the wells. The prior claimed to be a distant relative of Montgomery's. "Very well then," replied the regicide; "I shall render you the honours due to your birth and you shall be hanged from the main gate." The sentence was executed without further delay.

In Henri de Navarre, the Huguenots now had at their head a powerful contender for the French throne, while the future looked increasingly bleak for Catherine's sickly litter of children. The reign of Francis II had lasted barely a year. It was no secret that Charles IX, aged nineteen when Montgomery recovered Navarre, lay at death's door. He cut a poor figure for a warrior king.

By the following spring, 1570, Henri de Navarre was advancing on Paris, with Montgomery at his side. In Paris, a mood of nervous foreboding developed. Catherine dispatched her top diplomats to La Rochelle and another peace was finally signed at Saint-Germain-en-Laye on 29 July 1570. Both sides were exhausted by war. The terms were much the same as the Peace of Amboise several years earlier. But there was a secret clause which created some novelty: Henri de Navarre was to marry Catherine's only healthy offspring, Marguerite, who would be remembered in history, fiction and film as the tragic Queen Margot.

There was, in fact, around 1570, a spate of dynastic marriage proposals throughout Western Europe. Though no guarantee, it remained in a world that was still in many ways medieval the surest route to peace: marry the leading opponent and, in the good feelings generated by the feast and the princely honeymoon, old rivalries could be buried. In 1570 the Spanish and German Habsburgs were busy arranging marriages into French, English and Scottish royalty. The Guises hoped Margot would marry Henri, the young duke—who was caught in her bedroom one morning in spring. The most hopeless project of the time was between Elizabeth of England and Catherine's youngest son, the Due d'Alencon. When negotiations began in 1572, the Queen was entering her fortieth year while the mad, pockmarked duke was exactly half her age. The Montgomery family enjoyed greater success. Shortly after the Peace of Saint-Germain was signed his wife, Isabelle, travelled to England and negotiated the marriage of their daughter, Roberte, to the Vice Admiral of the English Fleet, Sir Arthur Champernowne, who also happened to be Governor of Jersey. The wedding was celebrated on 15 December 1571 in the Royal Chapel of Greenwich before the Virgin Queen.

The marriage in December 1570 of King Charles IX to the exquisitely beautiful Elisabeth of Austria, daughter of the Emperor, enchanted the crowds in Paris and guaranteed the peace between the houses of Habsburg and Valois. But the critical marriage between Catholic and Huguenot, Margot and Henri de Navarre, did not look at all promising. Margot was revolted by the idea. She had been severely beaten up by her elder brothers, the King and the Due d'Anjou, for her flirtation with the Due de Guise. Henri de Navarre may have looked athletic but Margot had scented that, unwashed, he smelled of the southern sun and garlic.

The events leading to the marriage did not augur well either. Jeanne d'Albret died in Paris on 4 June 1572 after exhausting herself in the preparations. There was talk in Paris of poisonings and murder; and thoughts of la sonoria were not far from the minds of those who governed. Others were worried. Paris, with its narrow unlit streets, its dead-end alleys, its walls and moats, along with its fanatically Catholic population seemed a perfect trap.

The Huguenots rode straight into it. Henri, whose mother's death would make him King of Navarre, left his seat at Pau on 23 May 1572. On his way north he gathered around him all the major Protestant leaders of France. News of Jeanne's death did not delay the procession's progress. Montgomery left his estate of Ducey around 20 June and joined Henri at Blois from where a retinue of nine hundred Huguenot gentlemen, all dressed in black, headed directly for Paris. At the Porte Saint-Jacques the entire corps of the city's militia were there to greet them. They rode up a street called Hell to join Catherine's court at the Louvre. For the Catholic denizens this black procession must have been an awesome sight. For Montgomery, who rode immediately behind Navarre, the stifling summer's heat must have carried a few memories.

There can be no doubt about Catherine's plans to murder the Huguenots, though just how extreme was her first intention will never be known. Her most recent biographer, Leonie Frieda, attempts to shift the blame for what followed to the bellicose Huguenot leader, Admiral de Coligny, who not only encouraged King Charles to invade the Spanish Netherlands but sent in a preliminary force of 5,000 on 17 July. The Spanish trapped and slaughtered most of them at Mons; only a few hundred escaped to tell their tale. In Catherine's view, a war with Spain would have destroyed her kingdom and delivered what remained to the Protestants. Blame a warmongering victim for the atrocities committed by the murderer: historically, this has never been a good argument— every modern tyrant has used it.

An emergency meeting of the Royal Council on 10 August voted against an invasion of the Netherlands. Coligny's was the only dissenting vote. That is what sealed his fate. The next day Catherine and her soldier son, the Due d'Anjou, were plotting his assassination. The Huguenots rode straight into it. Henri, whose mother's death would make him King of Navarre, left his seat at Pau on 23 May 1572.

Catherine's original project seems to have been simple: first the marriage and celebrations, which were to last until Thursday night, 21 August; then the murder, Friday morning, as Coligny stepped out of the first Council meeting after political business had been resumed. The Guises selected for the job their favourite murderer, a Gascon captain named Charles Louvier de Maurevert, who had shot his own tutor in the back. Anne d'Este, Duchesse de Nemours, whose first husband had been the assassinated Due de Guise, selected the house from where the shots would be fired: a nice quiet little place just north of the Église Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois, overlooking Rue des Pouillies, which Coligny would take to get back to his palatial lodging on the corner of Rue Béthisy (today at the level of No. 144, Rue de Rivoli). The Guise family tutor lived there. According to the memoirs of the Due d'Anjou this simple plot had been hatched several days before the marriage. But history is never simple.

The rituals of marriage were pushed through with great haste. Margot became the King of Navarre's fiancee in a betrothal ceremony held at the Louvre on Saturday afternoon, 16 August. On Monday morning she was his queen.

Montgomery had been refused the right to be present at court, so he took up residence on the left bank in the Faubourg Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Site of the greatest fair in Paris, Saint-Germain had become the quartier of the Huguenots, many of whom were recruited from the commercial classes. Indeed, this was where Calvinism had been invented before its master, Jean Calvin, took flight for Switzerland. Heretics lived here (it was not perhaps a pure accident that, four hundred years later, this would be the birthplace of Existentialism). It was the one part of town where Huguenots felt safe.

Temperatures soared during that third week of August. The atmosphere was oppressive, muggy In the churches Catholic priests denounced the royal wedding and the presence of the anti-Christs within the city walls. There were fights in the streets, duels in the alleys. Montgomery, forbidden to attend court festivities, reported to Coligny all that he heard and saw in the streets: this was no town for gentlemen in black to go walking. Coligny thanked the Lieutenant General, replying that his presence in the city was required to avert another civil war. But as a precaution he did ask Montgomery, on Thursday night, to accompany him to the King's Council the next morning. The alleys around the Louvre were very narrow.

Coligny was still intent on pursuing his war in the Netherlands, but he got no support in the Council; the King, his only potential ally, was attending mass. The session ended a little before 11 a.m. Montgomery, with other attendants, was there at the exit. On their way across the courtyard they met the King on his way to a match of tennis; there was a bowing and a swirling of caps. Then they proceeded along Rue d'Autriche, down Rue des Pouillies to where it turned into Rue des Fossés-Saint-Germain. Maurevert was waiting with his twin-barrelled harquebus. He squeezed on one trigger—at that very instant Coligny bent down to tighten a leather lace that had loosened on one of his boots. Then he squeezed at the other—the second bullet nearly severed Coligny's left index finger and ran up his arm to lodge in his elbow. "You see how one treats decent men in France!" screamed the Admiral. "The shot came from that window. There's the smoke!"

Montgomery and his men, after checking that the wound was not fatal, raced over to the house. They found the gun, still smoking, and two servants; but the culprit had made a quick getaway out the back by horse. They returned to their master and carried him to his home on Rue Bethisy At his bedside Montgomery proclaimed that he would put every Guise in town to death—he had little doubt who was responsible. Coligny calmed him down.

The Spanish ambassador Diego de Zuñiga was present at the meal which Catherine had just begun when the news was brought of the attempted assassination. She remained expressionless, though secretly she must have realized that she and her whole family were now in mortal danger; she calmly got up and retired to her chamber. King Charles, unaware of his mother's intrigue, was still playing tennis. On hearing the news he squealed, 'Am I never to be left in peace? More trouble! More trouble!" He decided to go and see Coligny himself. When Catherine heard this, she hypocritically suggested that all the senior members of the court go over to Rue Béthisy that afternoon.

Huguenots were already on the rampage. All the Guise properties were stoned. There was skirmishing in the streets and a murder or two. The court arrived at Rue Béthisy shortly after the royal surgeon Ambroise Pare—the same surgeon who had attended to Henri IPs fatal wounds-had succeeded in cutting off Coligny's finger, with scissors that "were not well sharpened," and retrieving the bullet from his elbow. Montgomery diplomatically took leave and Coligny stoically received his royal visitors. "You, Admiral, must support the pain while I, I have to support the shame," said a distraught King Charles bending over the bed. The King returned to the Louvre and ordered an immediate enquiry into the affair; by Saturday the complicity of the Guises was evident. The Queen Mother meanwhile determined, in the words of Anjou, to "finish the Admiral by whatever means we could"; on Saturday afternoon a "war council" of plotters met in the Tuileries Garden and determined to put an end to all the Huguenot leaders, so conveniently gathered in Paris. That evening the gates of the city were closed, chains were laid in the river to prevent boats from crossing the Seine and the Prévôt des Marchands ordered the city rnllitia to collect at the Hôtel de Ville to prevent pillaging should the mobs run amok that night.

King Charles could not be kept out of the picture forever. Catherine asked the Comte de Retz to go to his study to explain. The King's dismay was great. He burst into tears, protesting that the Admiral loved him as he would his own son, but after Retz had noted that the lives of him and his family were in peril, he cried out, "Then kill them all! Kill them all!" The number of Huguenots to be murdered increased with every hour.

Assassins were selected for specific victims. The young Due de Guise was responsible for putting Coligny to death. Captain Claude Marcel of the bourgeois militia had the task of killing Montgomery. The slaughter was to begin at 3 a.m. with Coligny's death and the sound of the grand bell at the Palais de Justice, the death knell, la sonoria. Sunday was 24 August, the day dedicated to the memory of Saint Bartholomew, one of the twelve apostles, the one flayed alive by the Armenians.

On Saturday evening Montgomery, having supped in Saint-Germain, crossed the river to visit Coligny at Rue Bethisy. The Admiral was cheerful and seemed to be recuperating well from his wounds. Montgomery suggested that he and some of his soldier friends guard the building that night, for the assassins were still at large. One of the Huguenot captains assured him that there were already enough guards in the house. So Montgomery returned to Saint-Germain. He took his time. It was a beautiful summer's night when one could stare in wonder at the stars of heaven and down through the empty, quiet streets. A few of the Paris militia were on patrol; Montgomery noticed for the first time that they had white scarves tied around their left arms—no doubt to identify themselves, he thought. At Saint-Germain he paid a short visit to the English ambassador Sir Francis Walsingham, who lived in the neighbourhood. Walsingham was pleased with the rapid progress being made by the King's enquiry and was sure the guilty men would soon be rounded up. Montgomery got back to his own lodgings by the Tour de Nesle at around midnight. He was anxious and had difficulty sleeping.

He was wakened at three or four in the morning by a stranger in his room. He reached for his sabre. "The whole town is in commotion," came a haggard reply; "they're Protestant bashing, I only escaped by diving into the river." The man ran to the window: "Sound the alarm! Sound the alarm!" Montgomery heard a bell tolling—it was actually Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois—the screams of men and women and the pattering bursts of harquebus shot. His first thought was to get to his colleagues on the other side of the river. He and a few friends managed to find a small dinghy and get out to mid-river where they were turned back by a rain of gunfire. Many of his colleagues, he realized, must already be dead. It was a question of saving his own skin.

Coligny had died bravely. Hearing the commotion below as Guise's men forced their way into the house, Coligny knew his time had come. He told the men about him, "For a long time now I have been preparing for death, save yourselves for you cannot save me." And pausing, "I will commend my soul to God's mercy "The door, blocked by a chest of drawers, was forced open; a rough Swiss guardsman thrust his sword into Coligny's breast, beat him on the head and then threw him through the window. Coligny's fingers were seen grabbing at a ledge before he fell two storeys at the feet of the Due de Guise, who kicked the corpse with delight. The Duke then galloped about the Louvre—where Huguenots were dragged into the courtyard and impaled on Swiss pikes—until he heard the bad news: Montgomery had got away Guise joined the pursuit.

Montgomery and his companions had charged through a line of irulitia blocking the road at Vaugirard and continued west through the countryside, passing Issy-les-Mouilneaux, Saint-Cloud and the Versailles Forest. Guise and his men gave up the chase at Montfort-l'Amaury Montgomery and company were hiding among the trees. At the forest crossroads of Bel-air they separated; country ramblers today will find a stone monument there, known as "Montgomery's Cross."

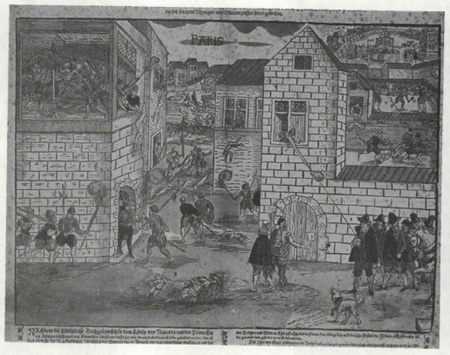

In Paris the slaughter continued for at least three days. As many as three thousand perished, many of them not even Huguenots. Mass murder spread into the provinces, finally petering out in Provence in October. How many died in those three months will always be one of the mysteries of history; estimates vary from ten thousand to thirty thousand. "But yet the King to destroy and utterly root out of his Realm all those of that Religion that we profess," grieved Queen Elizabeth of England, "and to desire us in marriage for his brother, must needs seem unto us at the first a thing very repugnant." All the senior officers of the Huguenot forces had been wiped out, save one, Sieur Gabriel de Montgomery.

Just as he had done after the jousting accident, he fled to Jersey But this time he did not get the support of Elizabeth. The Queen, despite the "thing very repugnant," not only maintained relations with Catherine's court but, incredibly, continued to negotiate a marriage with Catherine's revolting youngest son, the Due d'Alencon. At home she had started to move against Puritanism and "prophesyings." Abroad she had to deal with the consequences of Catholic terrorism, not in France but in the Netherlands, which the Spanish were subjecting to a regime of mass starvation and slaughter. An unexpected offshoot of this was a rapid rise in Protestant piracy in the Channel and the Atlantic; William the Silent's "Sea Beggars" were using fifty- or sixty-ton man-o'-wars to rob boats of their cargo and murder their crews—and unfortunately many of their victims were English. Elizabeth closed all English ports to the Dutch privateers and threatened to form an alliance against them with Philip of Spain, the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian, and the German princes. So the pirates had to go elsewhere for support. And it was obvious where: the French Huguenot ports. And who would be their principal collaborator? Sieur de Montgomery at his base in Jersey.

There was another "Flight from Egypt" on to La Rochelle. Charles IX declared war on the port on 5 November 1572 and sent his brother, the Due d'Anjou, with an army of 5,000 to introduce its inhabitants to a little Spanish treatment. After five months of siege the town showed no sign of yielding so Anjou attempted a frontal assault, which cost his army many lives. Then, in April 1573, Montgomery and a fleet of international pirates appeared on the horizon; they took on Anjou's naval force and nearly lost their flagship, the Primrose, in the process— Montgomery did not make a very talented buccaneer. But he did manage to seize the offshore islands of Belle-Île and Îie d'Yeu, which made it impossible for the French royal fleet to supply their army: it was Anjou's army that was starved out of action, not La Rochelle, which, thanks to Montgomery, received ample food and booty estimated at two million gold écus. Catherine sued for another peace, granting the same religious liberties as all the previous ones. Montgomery set sail for the Isle of Wight, where he anchored on 26 May.

But in England he was now persona non grata. Montgomery spent several weeks negotiating with the French ambassador the right to live in Normandy. Then he returned to Jersey, where, with the help of his pirates, he amassed enough money and arms to seize Normandy. In early spring 1574 he almost succeeded. "We hold the whole country in subjection," he boasted on 24 March to his old friend Lord Burghley as Sir William Cecil was now known.

Catherine sent reinforcements to Montgomery's erstwhile foe, the Comte de Matignon, who began a huge pincer movement into the bocages, or bosky country, of rebellious western Normandy. By a series of zig-zag manoeuvres Montgomery managed to get away each time Matignon thought he had cornered his prey He got away until he reached the medieval fortress of Domfront, where, because of an argument he had with the Huguenot captain who held it, Ambroise Le Hérice, the "Scarface," he was delayed a fatal twenty-four hours.

TRAVELLER OF THE Paris métro, if you have the chance, take an excursion to Domfront in "Norman Switzerland." It is one of the most impressive medieval citadels in France, though the fort itself was blown up by gunpowder in 1610 on the orders of Henri IV's minister, the Due de Sully. The town was the site of Allied aerial bombing during Hitler's Mortain offensive in August 1944, but the medieval quarter survived. The cafés serve poiré, the local pear cider; the remaining walls and turrets, often shrouded in mist, inspire thoughts of medieval legend and terror— the parapets were designed for pouring burning oil on the attackers; you get a grand view across the Norman bocages; and a stroll along the surrounding defences and the steep cliffs will give you an idea of the drama of Sieur de Montgomery's last stand.

Matignon's first troops arrived early on a Sunday, 9 May 1574. Within hours they controlled all roads of access and by afternoon his pioneers were felling the trees on the south side of the fort, in preparation for a massive bombardment. Montgomery attempted a sortie the following morning at dawn, but Captain Mouy de Riberprey's royal cavaliers put an end to that within yards of the portcullis.

The largest cannon available in Normandy were dragged in by horse and hauled up the surrounding heights—a feat worthy of the Pharaohs. From the artillery park of Caen, Matignon had transported a five-yard long, thirty-three-inch calibre monster called "Mad Marguerite," possibly after Henri de Navarre's Queen. It was placed on the summit of Le Tertre Grisiere. On the hills of La Rouge Mothe there were six culverins, each one of them over fifty hundredweight and ready to fire after mass was sung on Sunday, 23 May. At seven o'clock that morning Mad Marguerite crashed out at the curtained fortifications of the main castle; the cannon of La Rouge Mothe strafed the battlements. Matignon had under his command six thousand infantry and two thousand cavalry. There were just seventy Huguenots inside Domfront; they sang psalms as they went into action.

In the old castle fortress of Vincennes, just outside Paris on the east side of the Bastille, King Charles IX was dying. He was not yet twenty-four. "I can give death, but you can give immortality," he had whispered to the court poet Pierre de Ronsard. Tormented by his role in the Saint Bartholomew massacre, torn between loyalty to his mother and a will to be free, he lay sweating and coughing in blood-stained sheets. Catherine could be heard singing in a nearby chamber—for she had heard that the regicide had been cornered. When the news was announced to Charles he replied, "Human things no longer mean anything to me." Yet he revived to sit up and announce, "My cure will come with the capture of Domfront and the surrender of Montgomery."

The steep river valleys around Domfront echoed to the sounds of bombardment and crumbling walls that Sunday, 23 May. Around midday two gaping holes had been blasted out of the curtain defences on the south side of the citadel and in the wall of the castle itself. Matignon's infantry clambered up the southern bluffs only to be met by Huguenots wielding their swords and sabres; Montgomery himself appeared in a white doublet braided in silver, as if dressed for a banquet, except for the axe in his right hand. His foe of yesterday, "Scar-face," fought by his side. With the sun disappearing over the horizon, Matignon ordered a retreat. He had lost over two hundred men. Montgomery had won a brief respite.

Monday and Tuesday were limited to further bombardment. On Wednesday night Matignon sent in a messenger, the Baron de Vassé— one of Montgomery's own relatives—but he was peremptorily dismissed. Yet only fifteen men were left in the castle; they had no water, no food, no powder. De Vassé returned three times on Thursday. The situation was clearly hopeless. Between one and two o'clock Friday morning, 28 May, Matignon himself accompanied de Vassé to summon the surrender. Montgomery appeared in the reception hall, this time dressed "in a high hat and a short leather doublet." He received all the honours of his rank; he kept his sword and his dagger. He was even promised his life.

King Charles IX lived just long enough to receive news of the capture; it arrived at Vincennes on Saturday. On Sunday, 30 May, he lost consciousness. Queen Catherine sat at his side, holding his hand. Then suddenly he exclaimed, in a voice so clear that it could be heard by all in the room, "Adieu ma mère! Eh, ma mère!"—and died.

Montgomery was escorted to Paris where he arrived on 16 June. He was imprisoned in the Conciergerie. On 26June the Paris Parlement

sentenced him to "be decapitated and his body to be cut into fourteen quarters." The sentence was carried out on the Place

de Grève the same afternoon. "Quandsongerey à moi" concludes the ballad, — do not ever, even in play, set yourself against your master.

jugez, seriez vous vrai

qui vous donne à cognoistre

qu'il ne faut point vouer

encore moins se jouer

jamais contre son maitre

In his lovely essay Homo Ludens, "Man the Player," written on the eve of the Second World War, the medievalist Johan Huizinga argued that there had always been a play element in war. "Young dogs and small boys 'fight' for fun, with rules limiting the degree of violence," he commented, and then noted that the level of acceptable violence in war games did not necessarily stop at the spilling of blood or even killing; he gave the example of jousting. Sieur de Montgomery of Normandy was a player to the end.