Before it became the world center for the production of entertainment and art, Los Angeles was just the end of the line. When you got there, you had gone as far as you could go.

It was an exotic place, and for a very long time it was also a bit unreal. Maybe it still is; I’ve been here so long—more than seventy-five years—that it just seems normal to me. But if you go back to the beginning, it was a place of open spaces and dreams that took a long, long time to come to fruition.

Before the movies, people came to Hollywood for the same reason they went to Florida: the weather. And before smog created temperature inversion, the weather was indeed glorious—seldom over 85 degrees in the hottest summer, rarely below 40 degrees in the coldest winter.

Hollywood was founded in the 1880s by Methodists from the Midwest who saw it as a place where temperance could flourish. First they banned liquor. A few years later, they banned movies.

Neither ban succeeded, thank God.

But everybody who came to Southern California then came to Los Angeles, not Hollywood. The population of Los Angeles skyrocketed from eleven thousand people in 1880 to fifty thousand ten years later, making it the fastest-growing city in the country. All that land west of Los Angeles was bound to become desirable, but when?

Developers appeared early. One of them was Horace Wilcox, who arrived from Kansas in 1883. Wilcox was a devout Methodist who had made a fortune in real estate and helped make Kansas safe for Prohibition.

Wilcox built a gabled Queen Anne house on a dirt road that he modestly named Wilcox Avenue, in a town that his wife named “Hollywood” after the name of a friend’s estate in Ohio that she thought would work well for an entire town. Daeida Wilcox wanted Hollywood to be at the leading edge of the Temperance movement, a model of virtue that would set Christian soldiers marching as to war.

Wilcox offered free land to anybody who wanted to build a church. There were no saloons or liquor stores, no red-light district, and, above all, no theater people. The sign that was most frequently displayed read “No Jews, actors or dogs allowed.”

I don’t know about the dogs, but the Jews and actors were not easily discouraged. They bided their time.

As a temperance venture, Hollywood has to be considered a huge failure; as a real estate venture, an equally huge success.

Horace Wilcox died in 1890, and Hollywood was incorporated in 1903. In between those years, not a lot happened, aside, perhaps, from the construction of the Hollywood Hotel in 1903. Built along a Hollywood Boulevard that was then still a dirt road, the hotel was an old frame barn, part Moorish, part Spanish. It cost twenty-five thousand dollars, had thirty-three rooms, a bathroom on every floor, and a garden on the roof.

Sometime during World War II, I walked onto the veranda of the Hollywood Hotel and saw D. W. Griffith sitting in one of its rocking chairs, quietly surveying the town that he had done so much to build. Just a few years later, both Griffith and the hotel were gone.

The development of the modern Hollywood was an incremental process. A few highlights from its early history:

1904: Sunset Boulevard is completed from downtown Los Angeles to Laurel Canyon.

1905: Hollywood Cash Grocery, the very first store, opens on Cahuenga and Sunset.

1905: A trolley car begins running between Los Angeles and Hollywood every fifteen minutes.

A few places still survive from that era, although they’re not in Hollywood proper but in Los Angeles. There’s Olvera Street, which dates from the founding of the town. Then there’s a restaurant with the delightful name Philippe the Original, which opened in 1908 on North Alameda Street and became famous for its French dip sandwiches served in a rustic atmosphere. It’s still offering them, among other dishes. And the Pantry Café, which opened a little later, in 1924, on South Figueroa, is also still in business.

One of the early landmarks from that period was a mansion built by the artist Paul de Longpré in 1902 on three and a half acres on the corner of Hollywood and Cahuenga Boulevards. De Longpré was a mostly unsuccessful artist in France and New York who got that prime plot of real estate by bartering three original oil paintings for it. He proceeded to build a Moorish-style mansion and surround it with a spectacular Monet-style garden: five hundred rose bushes, a thousand tulip bulbs, jonquils, and fifty blooming trees. His skills as an artist paled next to his skills as a promoter; the public was invited to saunter through his home and garden. If they bought a painting or two en route, so much the better.

De Longpré’s house was the first famous Hollywood mansion, and you might say that he also invented the modern American tourist attraction, which also functions as a glorified souvenir stand.

And while de Longpré’s home is not among them, there are a number of hardy early-twentieth-century Hollywood survivors. (I’m partial to hardy survivors.) The Magic Castle, a Franklin Avenue landmark for decades as a place where magicians go to amuse other magicians, was built as a private home for a man named Rollin B. Lane in 1909. Yamashiro, a Japanese restaurant in the Hollywood Hills, was originally built in 1914 as a home by the Bernheimer family, leading New York importers of East Asian goods. They probably figured the house would be on the decorative leading edge, although the style never quite caught on, at least not in LA. After the stock market crash of 1929, the house passed through several hands until it was resurrected as a restaurant in 1949. All told, the buildings and the beautifully landscaped grounds have been Hollywood landmarks for a hundred years.

By 1911 Hollywood had banned anything that might lower the tone of the town: slaughterhouses were forbidden, as were gasworks, textile mills, and cotton fields. Why cotton fields? Because they required people—usually migrants—to pick the cotton; in addition to Jews, actors, and dogs, migrants were also unwelcome.

What flourished in Hollywood was not tolerance, but nature. Franklin Avenue was wreathed in pepper trees; Vine Street was covered in peppers and palms. Snaking through the hills but stopping far short of the ocean, Sunset Boulevard had a bridle path that ran right down its center. This made perfect sense, because a lot more people were getting around via horseback than via automobiles.

Between 1903 and 1910, Hollywood’s population gradually increased—from seven hundred in 1903 to four thousand in 1910—but the character of its people remained the same. They were middle-class families who wanted to get away from cold weather and alcohol. Among the things that the board of trustees banned were the sale of liquor, gambling, and “disorderly houses”—i.e., whorehouses. As for pool halls and bowling alleys, they had to be closed by eleven p.m. on weekdays and all day on Sunday.

Other laws prohibited driving herds of more than two hundred horses, cattle, or mules, or more than two thousand sheep, through the streets. All that was official; still unofficially prohibited were actors, who couldn’t find rooms to rent.

Things finally began to change when Cecil B. DeMille set up shop in December 1913 at a barn on the southeast corner of Selma and Vine in the heart of Hollywood. He was representing a consortium in New York that included Jesse L. Lasky and Samuel Goldwyn.

The Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company was not the first movie company to have offices in Southern California, but it was the first to establish year-round headquarters; the others were seasonal operations sent out by East Coast studios that were trying to maintain production during the impossible New York winters.

DeMille hadn’t intended to end up in Hollywood; his original destination had been Flagstaff, but finding that he hated the light and the flat terrain in Arizona, he went on to the end of the line. Scanning the horizon for a likely place to set up a motion picture studio, he ended up at a barn owned by a man named Jacob Stern. A deal was struck, and DeMille erected a sign over the barn: JESSE L. LASKY FEATURE PLAY COMPANY. DeMille started shooting his first picture, The Squaw Man.

Members of the Famous Players–Lasky Corporation, which eventually became Paramount. From left to right: Jesse L. Lasky, Adolph Zukor, Samuel Goldwyn, Cecil B. DeMille, and Al Kaufman. In the end these men created more than Paramount—they created Hollywood.

Mary Evans Picture Library/Everett Collection

It was a western, and it was a smash hit. DeMille had lucked into something big. As he ramped up production, he found that the area could serve as background for almost every kind of movie, from desert—about eighty miles outside of Los Angeles—to mountains—fifteen minutes from DeMille’s studio door.

Other studios noted the variety of locations. The gold rush was on.

I have a holster that was used in The Squaw Man, given to me by a wonderful man in the Fox still department who had worked on the picture. When I got into the movie industry in 1949, The Squaw Man was only thirty-five years old, or about as old as The Deer Hunter is now—lots of people who had been there with DeMille were still working, as was DeMille himself. The holster is one of those six-degrees-of-separation objects—a perfectly ordinary piece of leather that is also a piece of Hollywood history.

For the first few years of the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company, Lasky himself commuted from New York and basically left production matters in the hands of his partner DeMille. But in 1917 Lasky bought a Spanish mansion at 7209 Hillside, right where La Brea dead-ends into the Hollywood Hills. The Lasky house’s most exotic feature was a screening room—one of the first private screening rooms in Hollywood—along with the already standard tennis court and swimming pool. Lasky wouldn’t have needed more than five minutes to get to the studio.

By 1915, the annual payroll of the studios in Hollywood totaled about twenty million dollars. By 1920 the population had grown to thirty-six thousand, and the new settlers were no longer teetotaling Midwesterners, but young men and women lured by the siren call of the movies.

There were still very few mansions in Hollywood, and hardly anything at all west of the town. Most of the aspiring actors and actresses, not to mention the writers and directors, rented hotel rooms or modest frame houses, if only because everyone was uncertain how long this movie thing was going to last and they didn’t want to overextend themselves only to be brought up short by the sudden death of the fad.

In those early years, people seemed to want to stay close to the studios, if only to keep the commute short. There were exceptions; around World War I, the most fashionable address in Los Angeles—at least between Western Avenue and South Figueroa Street—wasn’t in Hollywood at all, but on West Adams Boulevard. Theda Bara lived there for a while, just around the corner from the extremely rich oilman Edward Doheny.

After a time Theda Bara moved out, and Fatty Arbuckle moved in. This was even worse. Bara was at least an actress, but Arbuckle had worked for the lowly Keystone company. He was . . . a comedian! He was making five thousand dollars a week, but he was still—a comedian!

Arbuckle was living at his West Adams home in 1921 when the scandal erupted that destroyed his career and his life. He had thrown a party in San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel, after which a girl named Virginia Rappe died. Arbuckle was accused of manslaughter; there were allegations of rape as well, although nobody who knew Arbuckle thought he was capable of committing rape. After a few trials resulted in hung juries, he was acquitted, but he was banned from the screen by newly hired morality czar Will Hays anyway. Arbuckle sold the house to his boss—and later my boss—Joe Schenck.

Agnes de Mille would describe Hollywood at that point in its history as “very lovely and romantic and attractive. . . . The streets ran right into the foothills and the foothills went straight up into sage brush and you were in the wild, wild hills. Sage brush and rattlesnakes and coyotes and the little wild deer that came down every night. And all of it was just enchanting.”

Los Angeles didn’t have traditions of its own, so it borrowed the older traditions of California, a place of Spanish haciendas and missions and a sense of leisure. In good times and bad, one thing stayed constant in California: a feeling for light and the ways in which the land could be made a part of the interior of the homes. The houses were Andalusian or Moorish, Italian or Spanish, but almost all of them were in some way romantic—the basis for Los Angeles, as well as for the movies.

In those early days, Beverly Hills landscaping was in the hands of the Englishman John J. Reeves, who wanted a different kind of tree for each street, all trimmed to uniform heights and widths. Reeves specified pepper trees for Crescent Drive, just south of the future site of the Beverly Hills Hotel. J. Stanley Anderson, whose grandmother managed the Beverly Hills Hotel, told me that some of the developers thought that maybe pepper trees weren’t such a great idea, but Reeves insisted. He planted saplings, and they all blew down in the first storm, whereupon he was told to plant something sturdier.

“You are going to have peppers,” replied the stubborn Mr. Reeves. So the pepper trees were replanted and stood for decades, until they died off and were replaced with Southern magnolias. By that time, Mr. Reeves was dead and could no longer bulldoze his way through obstacles.

All this care and planning yielded . . . nothing much.

But they still kept planning, confident that if they just kept building, sooner or later the world would come. Los Angeles was the fastest-growing city in America, so some of that had to benefit Hollywood and Beverly Hills, which was right next door. In the early part of February 1911, Margaret Anderson and her son Stanley Anderson were invited to own and operate a luxury hotel. Margaret had another grandson named Robert, but years later I became very good friends with J. Stanley Anderson, who told me many stories of early Hollywood.

Everything exploded outward in the 1920s.

The first fortunes of Southern California were created by oil, agriculture, railroads, and real estate. In Beverly Hills, real estate and natural resources were closely intertwined. (Real estate is still a driver of the local economy.) About this time, 80-by-165-foot lots were going for $1,100—the rough equivalent of $26,000 today, which just goes to show you that scarcity and location have more to do with the value of a piece of land than inflation.

The Depression affected Hollywood in a different way and at a different speed than it did the rest of the country. While most other cities were already in terrible shape by 1930, Hollywood didn’t experience the full extent of the Depression until 1932 or so. Paramount went into receivership, RKO teetered, and Warner Bros. lost most of the money it had made in the early days of sound.

But by 1937, the year my family moved to Bel Air, the tide had turned. The town was once again beginning to hum, not just because of the quality of the movies being made, but because the studios manufactured one of the few means of escape for a world that was still struggling with the effects of the crash. And so Hollywood created an alternate reality—a collective fantasy, if you will—for a world where reality itself was ugly and unmanageable.

In 1937 MGM made forty-seven pictures, nearly one per week, while Universal came close to that, with forty-four movies—both amazing numbers. Yet Warner Bros. went far past them both, with sixty-six pictures. Hollywood was truly a factory, churning out movies the same way Ford churned out Model A’s. A lot of these movies were low-budget B’s, produced to fill the bottom of the double features that the studios had devised as a means of combating the economic downturn: two pictures for the price of one, with a dish giveaway in between them.

I first started going to the movies at the Carthay Circle in the Wilshire district almost from the day we started unpacking. I distinctly remember seeing Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs there—the grassy divider in the middle of San Vicente Boulevard, which ran in front of the theater, featured three- and four-foot-high figures of all the dwarfs.

In those days LA was a movie town to an extent that’s hard to imagine today. There was a big shipping business down by the docks in San Pedro and Long Beach—the second-largest port in the United States—but the driver of the local economy was primarily the movie business. In a few years World War II would change all that by propelling the airplane industry into prominence and broadening the economic base. Very quickly 750,000 people were working in the airplane business.

In 1937 I was seven years old, a kid from the Midwest—Detroit, to be specific. I was just beginning my love affair with the movies, which I was lucky enough to parlay into a career.

My father was a brilliant businessman. He made a great deal of money in the 1920s selling the lacquer that was used on the dashboards of Fords, then lost it all in the stock market crash and the Depression, when nobody had any money to buy new cars.

But by the latter part of the thirties, he had recovered enough capital to make the move to the West Coast, which had been recommended for my mother’s asthma. At the time, most of the movie people still lived in Hollywood or Beverly Hills; Bel Air was thinly settled at that point, but that’s where my father chose to live. I believe he paid twenty thousand or thirty thousand dollars for a lot, and around forty thousand dollars to build a house there. I’m not sure if there was a surcharge to construct the street to access it, but it was in any event as new as our house on 10887 Chalon Road.

The house is still standing, and, with the help of a great many people, so am I.

Our home had three bedrooms; next to it was a pool and a guesthouse. It was Spanish in style, and had a hitching post in the backyard for the horses we were expected to have, and did. We didn’t keep them at the house, but at the stables at the Hotel Bel Air when it finally opened in 1946.

I immediately loved California, the way each block offered something delicious for the eye. Compared to suburban Detroit, it was intoxicating. Not everybody, though, was enthralled with the prevailing mode of architecture and decoration. Nathanael West wrote about the environment in The Day of the Locust: “Only dynamite would be of any use against the Mexican ranch houses, Samoan huts, Mediterranean villas, Egyptian and Japanese temples, Swiss chalets, Tudor cottages and every possible combination of these styles.”

West was a good writer, but I didn’t share his feelings—not then, not now. Los Angeles, like the industry it spawned, was first about creating desire, then satisfying it—a profoundly American gift.

Bel Air had been opened to development by a man named Alphonzo Bell in 1922. And yes, at first there was a strict policy that forbade selling to movie people, which I find ironic. It seems that Bell wanted his development to become the “crowning achievement of suburban development” and he feared that nouveau riche Hollywood types would lower his property values.

In other respects, Bell was a farsighted developer. He carved roads out of hillsides and installed sewer, power, and water lines underground—expensive, but worth it. He also landscaped the place beautifully. The first tract he developed was two hundred acres, which he divided into parcels of several acres apiece, then encouraged buyers to purchase even larger lots of five and ten acres. He added polo fields, tennis courts, and my beloved Bel Air Country Club. He also built the Bel Air Stables on Stone Canyon Road and sixty-five miles of bridle paths.

And he installed the splendid gate at the Bel Air Road/Sunset Boulevard entrance. In the early days of the development, uniformed guards would patrol the entrance, making sure that no interlopers got in, and the private police force would escort visitors up the maze of streets to their destination.

All went swimmingly in the 1920s, but when the Depression hit, it was no time for artificial barriers to prospective buyers. Bel Air lots were going begging, and the area was teetering on insolvency, so Bell quietly let go of his strictures about movie people.

Colleen Moore, the popular flapper of the 1920s and a brilliant stock investor, bought a house on St. Pierre Road, and Warner Baxter came in about the same time. By World War II, movie people were setting up shop in Bel Air on a weekly basis, as it had become a more prestigious address than Beverly Hills. Judy Garland would build a ten-room Tudor house for herself at 1231 Stone Canyon Road, just up the street from the stables.

Bel Air had an interesting dynamic in those early years. Although you were only twenty minutes from Hollywood and its core industry, the town had a rural feel. Alphonzo Bell had his offices on Stone Canyon Road, and when he sold that property the office and the stables he had built there were redesigned and reconfigured to become the foundation of the Bel Air Hotel.

A lot of the rooms at the hotel were once horse stalls, and I’m particularly fond of a large circular fountain on one of the patios where I used to water my horse when I was a boy. Part of Bell’s property was converted into the Bel Air Tea Room, where I bused tables as a kid, with John Derek working alongside me.

Besides busing the tables, I washed dishes and occasionally waited on tables. It sounds like a typical summer job, but it was a life changer, because I became close friends with another kid named Noel Clarebut. Noel introduced me to his mother, Helena, who ran the dining room and the antiques gallery at the hotel.

Helena became a tremendous influence on my life. A European, she loved the theater, food, classical music, dogs—all the finer things in life. I didn’t have any of that. My family was Midwestern, with a utilitarian, bricks-and-mortar set of values.

Horses were very much a part of my life from the time we arrived. Robert Montgomery was responsible for making it easy to ride there, because he promoted the construction of bridle trails that wound their way through Bel Air in more scenic routes than were available in Beverly Hills.

My first horse was named Topper, after Hopalong Cassidy’s horse. He was a great horse, and I had him until his old age, when my father did exactly as Robert Redford’s character did in The Electric Horseman: he took Topper back to the breeder from whom he’d bought him. The breeder had a thousand acres, so Topper was unloaded into the pasture and slapped on the rear end, then went off to live out his days grazing. For Topper, life was a circle—he was born there, and he died there. At the time a lot of people didn’t fuss over their animals; they were part of the property more than they were part of the family, but I’m proud to say that my father didn’t feel that way, and he passed that same feeling on to me. Animals deserve nothing less.

A photo of me with my horse Sonny.

Courtesy of the author

Sonny was another horse I adored. He was a gentle soul, brown, with big hips and splashes of paint on his shoulders. Technically he was my father’s horse, but Sonny and I bonded in a very special way. His previous owner had taught him a routine that I maintained and amplified at performances at shows and fairs.

We’d make an entrance with him pushing me out. I would pretend to trip and fall. Sonny would lie down next to me, and when he was flat on the ground I’d grab a strap that was around his stomach. He’d get up and lift me with him, and I would hop on his back. We’d make an exit, then come back with an American flag in Sonny’s mouth. He’d toss his head a few times, which caused the flag to wave, and the crowd would reliably go nuts. Then he would take a bow.

For a boy who loved horses and was beginning to love applause, it was a surefire act, and a lot of fun to perform.

Years went by and Sonny got cataracts, so, just as he had with Topper, my dad took him back to the breeder. I got a chance to say good-bye to him, but losing him bothered me for years. It still does.

It sounds impossible now, almost like something out of science fiction, but the fact is that before and after World War II Los Angeles had one of the best mass transit systems in America. Electric streetcars connected Orange, Ventura, Riverside, and San Bernardino Counties with no exhaust and no smog—the trolley lines ran on overhead electric wires.

Los Angeles and the suburbs around it were expanding exponentially all during my childhood, but the air remained remarkably clean. I know: I rode those streetcars because that’s how I went to the movies. Occasionally I would take my bike and head to Westwood to see a movie. But if the film I wanted to see was in Hollywood, it was too far for the bike ride, so I’d walk from our house to UCLA, and grab a bus to Beverly Hills, then catch the trolley. (Occasionally, my father would drive my mother, my sister, and me, and sometimes he’d even come in with us.)

The trolleys began in 1894 with horse-drawn cars. By 1895 there was an electric rail line connecting Los Angeles and Pasadena, and a year after that a line opened that connected Los Angeles with what would become Hollywood and Beverly Hills, all the way to Santa Monica.

During World War I you could go from downtown Los Angeles to as far away as San Bernardino, San Pedro, or San Fernando on the trolleys. There was a trip called the Old Mission that went from Los Angeles to Busch Gardens, all the way to Pasadena and San Gabriel Mission. The Mount Lowe trolley, which was actually a cable car on narrow-gauge track, went to the top of Echo Mountain. The Balloon Route ran from Los Angeles through Hollywood, Santa Monica, Venice Beach, Redondo, and back to Los Angeles via Culver City. (I shudder to think how long that round trip must have taken.)

Two trackless trolleys (the first in America) running through Laurel Canyon.

Mary Evans Picture Library/Everett Collection

Apparently the trolleys took a hit in the 1920s as the population became more prosperous and people started buying cars, but with World War II, gasoline and tire rationing revived the trolley lines, and ridership hit an all-time high of 109 million in 1944.

By then, Los Angeles had two separate trolley systems, commonly known as the Red Cars and the Yellow Cars. Pacific Electric owned the Red Car line, and National City Lines owned the Yellow Cars.

I generally took the Red Cars, which ran from Union Station downtown all the way to the beach—an east-west line. To get there, it wound through the middle of Beverly Hills, through the upper part of Hollywood, then crossed over to Sunset. The Red Cars were great—they were fifty feet long, and ran between forty and fifty miles an hour.

The transit system was remarkably well engineered, efficient, and, in modern terms, environmentally sound. When I was riding the Red and Yellow lines they were at their height—there were nine hundred Red Cars running on 1,150 miles of track covering four counties. There aren’t that many people who remember them anymore, but they were a crucial factor in how Los Angeles developed the way it did. Because the trolleys made travel simple—not to mention cheap—they encouraged very expansive development. As late as 1930, more than 50 percent of the land in the LA basin was undeveloped. The population spread out over a very large area of land, which is why in my memory, and in my friends’ memories, Los Angeles seemed uncrowded and undeveloped—almost sylvan.

One of the red cars passing in front of Grauman’s Chinese Theater on Hollywood Boulevard. In an astonishing coincidence, Grauman’s just happens to be showing one of my movies.

Courtesy of the author

Of course, it all changed. The sheer expanse of Southern California made it perfect for the automobile, and the basic disposition of the American public toward independence probably made the decline of the trolleys inevitable. Making the changeover faster than it had to be was the dismantling of streetcar systems in favor of buses by a number of companies, including General Motors, Firestone, and Standard Oil, who stood to make a lot more money with buses than with electric power.

By the early 1950s, when I was a young leading man at 20th Century Fox, cars had displaced the trolleys as the primary means of travel in Southern California. Freeways that sixty years later are now often impassable, not to mention impossible, were being constructed. By 1959 the only trolley line that was still operating was LA to Long Beach, and that was discontinued in 1961. The trolley cars were chopped up and destroyed; some were sunk off the coast. It was a terrible waste of valuable historical artifacts.

If you want to see remnants of the great Los Angeles trolley cars, you can go to a museum in Perris, California, seventy-four miles (by freeway!) from Los Angeles, where they have both Red Cars and Yellow Cars on display. Now the only way you can enjoy even a vestige of trolley culture is to go to downtown Los Angeles and ride Angel’s Flight, a historical funicular that takes you just three hundred feet uphill.

One of the favored places in Southern California is the beach, where it’s warmer in winter and cooler in summer than it is farther inland. When people wanted to get out of town completely in the warmer months, they would often head for Big Bear or Lake Arrowhead, where the Arrowhead Springs Hotel was partially financed by Darryl Zanuck, Al Jolson, Joe Schenck, Claudette Colbert, Constance Bennett, and a few others.

(A word about celebrity financiers—they were usually like celebrities today who invest in sports teams. The amount of money that actually changed hands was minor; the stars were given some of the perks of ownership in return for whatever glamour their celebrity brought to the establishment.)

The Arrowhead Springs Hotel was in San Bernardino, in the mountains about two hours away from Los Angeles. When it opened in December 1939, its advertising proclaimed it “the swankiest spot in America,” and it just might have been. The “springs” element was not just an advertising slogan—the hotel was in fact constructed over hot springs that ran to 202 degrees Fahrenheit.

The resort was primarily the vision of Jay Paley, the uncle of CBS’s William Paley. The hotel was U-shaped, had 150 rooms spread over six floors, and three dining rooms. The most distinguishing thing about Arrowhead Springs was its interior, which was designed by Dorothy Draper. She rarely ventured west of the Mississippi, and certainly never soiled her hands with any project that would be patronized by show business types.

Draper was the designer for the millions; she had a column in Good Housekeeping and wrote bestselling books. What she ended up doing at Arrowhead Springs was a top-to-bottom design of the sort that was rare for the era. She designed everything. The dining rooms were done in black and white; they had oversize black-lacquered Chinese cabinets on the walls, huge plaster light fixtures, pink and white roses on the tables. The doormen wore forest green with red trim and silver buttons; the cocktail lounge was done in bleached walnut and Delft tiles. The swizzle sticks were black and red.

I went there only once or twice, and I can tell you that it felt like money. It also felt predominantly feminine, as if you were trapped in a layout from Vogue magazine circa 1940. Had it been 1940, it might have been more tolerable, but I was there somewhere around 1954. The Arrowhead Springs Hotel was in operation until 1962.

Six Hollywood fashion models at the Arrowhead Springs Hotel, circa 1948.

Time + Life Pictures/Getty Images

As it turned out, more people were interested in being by the Pacific Ocean than they were in poaching themselves in hot springs. They headed down to the ocean, first to Santa Monica, and then, as Santa Monica got crowded, to Malibu.

Malibu began to become more desirable, and gradually became more exclusive since there’s less land there. Oddly, however, it took longer to settle than Santa Monica. In 1891, the Rindge family bought all thirteen thousand acres of what was then called Rancho Malibu for ten dollars an acre. The Rindges held on to the property for more than thirty years, finally letting go in 1927. It was only then that show people began settling in what came to be known as Malibu Colony.

In 1930 or so, you could lease a lot with thirty feet of ocean frontage for thirty dollars a month. Dozens of people took advantage of that bargain, including Barbara Stanwyck, Warner Baxter, John Gilbert, and three great friends: Ronald Colman, William Powell, and Richard Barthelmess.

The colony in those days was protected by a high stone wall, with a gate manned by an armed guard. When I got to California, they were starting to build houses to the south of the colony, and even in the mountains alongside the Pacific Coast Highway.

By then Malibu residents had also begun looking out to the ocean, to see what they could see. What they saw was . . . Catalina. Literally. But that wasn’t unusual; all through the 1940s and into the 1950s you could see Catalina from Malibu. It seems impossible to believe now, but in that era you could even see Catalina from the hills above Hollywood, right up until the era when smog began to develop.

The particular charm of Catalina has always been that it’s basically uninhabited. Twenty-two miles long and eight miles wide, the island is home to only about four thousand people, the vast majority of them living in Avalon, the town’s only incorporated city.

Like Malibu, Catalina was for a long time the province of a single family—the Wrigleys, of chewing gum fame, who bought the island in 1919. William Wrigley Jr. spent the rest of his life preserving and promoting Catalina, and the fact that it remains so pristine is a testament to his foresight.

But Wrigley wasn’t the first to see something special in Catalina. George Shatto, who was, like me, from Michigan (Grand Rapids, to be exact), had bought the island for two hundred thousand dollars in 1887. It was Shatto who founded Avalon, and it was his sister who gave that city its name, inspired by the idyllic island Avalon referenced in Tennyson’s cycle of poems Idylls of the King.

But Shatto went bust, and the island existed in an uneasy limbo for a number of years. Los Angeles was only twenty miles away, and everybody knew that Catalina was destined to be some kind of vacation destination, but no one knew when its day would come.

World War I put a crimp in tourism. When it was over, Bill Wrigley, flush with money, was looking for something to be altruistic about, and Catalina turned out to be his project. Wrigley opened a mine there, along with a rock quarry, and he even started a plant that produced stunningly beautiful decorative tiles that he called Catalina Clay Products. All this only increased his passion for the island; he built a house on a hill overlooking the harbor and Avalon.

At that point, there were only two ships daily transporting people back and forth from the island to the mainland. Wrigley doubled the roster of ships, so now a lot more people could visit Catalina. In 1926, there were 622,000 visitors; four years later, the total was 700,000. What they saw was a very lightly managed natural wonderland, both on land and beneath the sea—Wrigley also kept a fleet of glass-bottom boats so that people could safely admire the marine life.

Most of the tourists were day-trippers, but they left a lot of money behind. I’ve been told that George S. Patton met his wife Beatrice on Catalina when they were children, but I’m not old enough to know if that’s true.

The movies came to Catalina gradually. In 1920 Harry Houdini did some filming there for Terror Island. Buster Keaton’s The Navigator was filmed off Avalon Bay. And whenever the studios needed a place to stand in for the South Pacific, they usually went to Catalina, as MGM did for the 1935 version of Mutiny on the Bounty.

By then Wrigley had built a splendid Art Deco dance hall called the Catalina Casino, which opened in 1929; the lower level houses a theater, the upper level the world’s largest circular ballroom. The influx of population made the island a kind of artist’s colony. Not only that, but the Chicago Cubs, which just happened to be owned by Wrigley, trained on the island from 1921 to 1951, with time out for World War II, when the island was used as a military training facility. From Wrigley’s study, he could watch the Cubs work out their winter kinks during spring training.

In the days before and after the war, Catalina was all about yachting, although there was also a smattering of aviators. The boaters clustered at either the Hotel St. Catherine or the La Conga Club, which had a private dock reserved for members’ boats. There were two yacht clubs: the Catalina Island Yacht Club in Avalon Bay, and the Isthmus Yacht Club in Two Harbors, whose building was built in 1864 as barracks for the Union Army. Then there was Moonstone Cove, a private cove operated by the Newport Harbor Yacht Club, and White’s Landing, just west of Moonstone, with two yacht club camps. I had a mooring at Emerald Bay for years.

Catalina offered superb fishing; the waters were roiling with garibaldi, yellowtail, kelp, white sea bass, giant sea bass, and bonito. And there were great numbers of abalone, although now they’ve been fished out.

Beyond fish that made for great eating, there were also barracuda, bat rays, horn sharks, and the occasional great white shark, the latter of which usually appeared on the west—or ocean—side of the island. I also remember the awe-inspiring sight of large schools of flying fish sailing out of the water.

It was in the 1930s that Catalina became a getaway for Hollywood folks. It now seems that I must have spent half my adolescence and young manhood on Catalina, and the other half at the Bel Air Country Club. How lucky can you get? I began spending a great deal of time at Catalina right after the war. John Ford and his crew of reprobates all docked their yachts at Avalon. Ward Bond was always there, as was Ford’s daughter Barbara and, for a time, her fiancé Robert Walker, who was unsuccessfully trying to get over his broken marriage to Jennifer Jones. Wherever you found John Ford and Ward Bond, you also found John Wayne, not to mention character actors like Paul Fix.

Ford’s group began organizing a series of softball games, and I was an occasional participant. I was Mr. Eager, happy to play anywhere, just to play. Mainly, I was at first base. Duke Wayne and Ward Bond had been football players at USC, and they were both natural athletes who also knew how to play baseball. The surprising thing was how competitive the games were. It was only a pickup game of softball, but as far as Wayne and Bond were concerned, it could have been the World Series—they both played to win. Ford was always there, but he didn’t actually take part much, which was odd, because he had been a champion athlete in high school.

Catalina also played a big part in my becoming an actor. It was while spending time on the island that I met Stanley Anderson. His stepdaughter had been hurt in an accident, and I enjoyed cheering her up by doing impressions of movie stars. I didn’t know then that Stanley was one of the founders of the Beverly Hills Hotel and had great connections in the movie industry. His stepdaughter liked me, and so Stanley would invite me on his boat. And later, he put in a good word for me with various directors and casting directors.

Stanley sent me to Solly Baiano, the casting director at Warner Bros. I did all my impressions for Solly—Cagney, Bogart, etc.—and he responded by saying, “That’s all very well, but we’ve already got Cagney and we’ve already got Bogart. What about doing you?”

I was totally stumped. “I can’t do me,” I said. “I don’t know who me is.”

It took a few years, but I eventually figured out who I was. By that time I wasn’t under contract to Warner’s, but to Fox.

Natalie and I spent a lot of time when we were courting on my first boat, a twenty-six-foot twin-screw Chris-Craft I had named My Lady. Natalie had never been to Catalina before I took her there, and it became one of her favorite places. After we got married the first time, we bought a thirty-two-foot Chris-Craft that we called My Other Lady.

In 1975 Phil Wrigley, the son of Bill Jr., deeded his family’s shares in the island over to the Catalina Island Conservatory, which controls 88 percent of the island. The island’s natural resources include six species of plants that are found only there. Other species unique to Catalina include the island fox, which was nearly wiped out by a strain of distemper; the population, which was down to less than one hundred animals in the 1990s, has now been restored to a level of over a thousand.

Then there are the buffalo. Yes, buffalo. How, you ask, did buffalo end up on this island? As with so much else, blame it on the movies. In 1924 Paramount brought fourteen buffalo to the island for a scene in their epic western The Vanishing American. When it was through shooting the scenes, the company decided to just leave the buffalo instead of going to the trouble of shipping them back to the mainland.

If you’ve seen The Vanishing American, you’re probably scratching your head—there are no buffalo in the movie. That’s because Paramount cut the scenes shot on Catalina. Ah, the wonders of the movie business!

But those fourteen buffalo flourished. The herd has grown over the years to about 150, and their numbers remain at that self-sustaining level. What the Wrigley family did for Catalina meant that the island remains one of the few unspoiled places in Southern California . . . and indeed the world.

As the movie industry expanded, the population needed more vacation destinations, which inexorably led to Palm Springs. The Springs got going in 1934, when Charlie Farrell and Ralph Bellamy bought up fifty-two acres of desert for thirty-five hundred dollars and started the Racquet Club as a way to defray some of their costs. Much to their surprise, it became a popular gathering spot for Hollywood actors who wanted to get out of town for a long weekend. Before the Racquet Club, there had been only the Desert Inn, which had been there since 1909 and was patronized mostly by victims of tuberculosis, who took bubbling mud baths at twenty-five cents a dip under the supervision of local Indians. A few years after the Racquet Club came the Palm Springs Tennis Club, but for the movie people the Racquet Club was always the main destination. Soon, the Racquet Club and all of Palm Springs had become a very posh resort. At that point, the main activities were tennis and horseback riding.

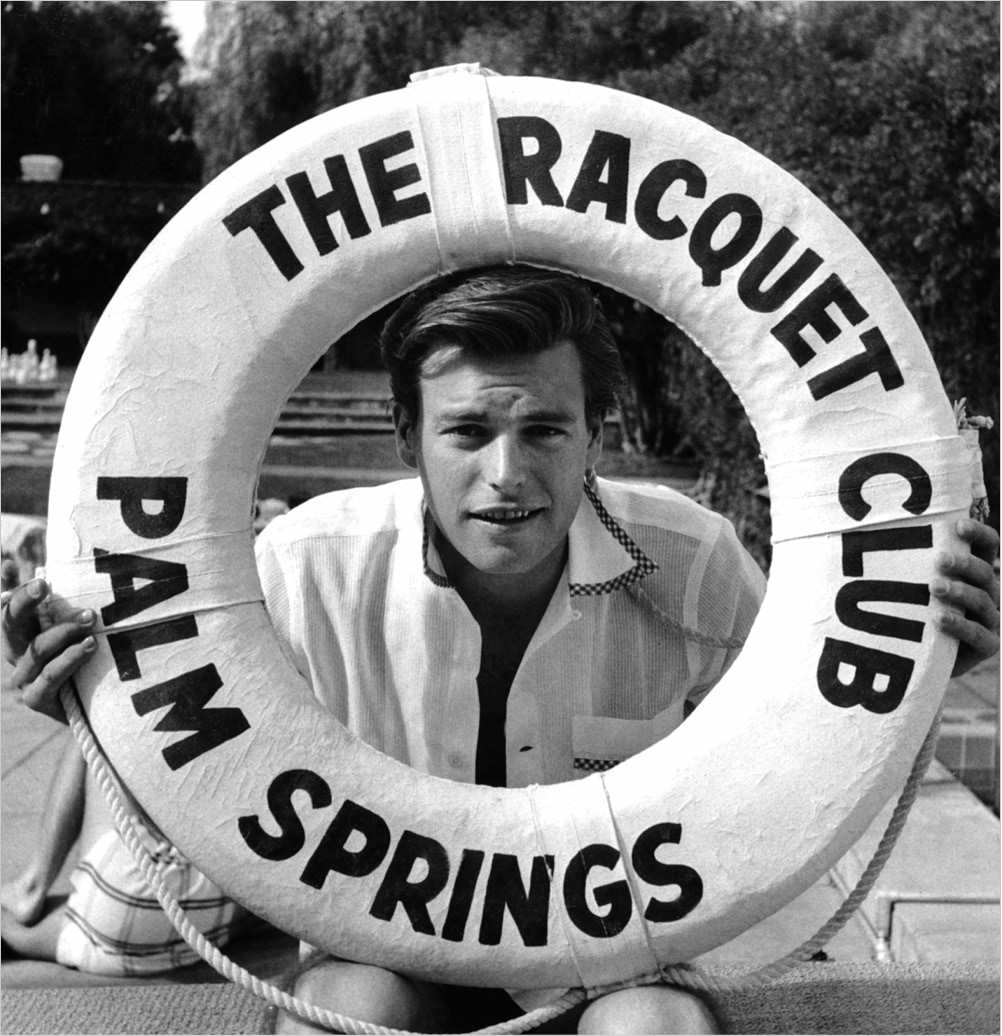

Here I am doing the publicity thing at Palm Springs Racquet Club.

Everett Collection

The attraction of Palm Springs was its hot, dry climate and complete seclusion, far from the studios and the gossip columnists. For years Palm Springs was one of the places you went if you were playing around on your spouse, or wanted to. The combination of a resort culture with geographical remoteness made for some wild times. As far as the people, it was the crème de la crème of the industry.

What was wonderful about Palm Springs was that it was an entirely different environment than Los Angeles, and yet it was only two hours away. Palm Springs is surrounded by mountains—the San Bernardino Mountains to the north, the Santa Rosa Mountains to the south, the San Jacinto Mountains to the west, and the Little San Bernardino Mountains to the east. It’s situated in a valley, and gets unbelievably hot in the summer—a temperature of 106 is normal, and it can go even higher, then falling to anywhere from 77 to 90 degrees at night.

Playing in a singles match at Palm Springs Racquet Club.

Everett Collection

But that’s in the summer. In the winter, it’s idyllic; it rarely gets over 85 degrees or so, and the nights are cool.

The first time I went to Palm Springs was before World War II with my father. I was immediately enchanted. We went riding in the desert, and tied our horses up at a place in Cathedral City where we bought delicious fresh orange juice.

Palm Springs then was the sort of town with no streetlights—after dark, the only illumination was the moon, but in the desert that’s much brighter than you think. I remember the mountains, the orange groves, the swimming pools, the desert sunsets, the air—so invigorating I always believed the oxygen content had to be higher than in the city.

Even then, the town had great bars. Don the Beachcomber’s had a beachhead there, as did the Doll House. And there was a restaurant called Ruby Dunes, which became one of Frank Sinatra’s favorite places.

Eventually, the unique environment of Palm Springs called for unique kinds of houses, and American modernist architects like Richard Neutra flourished there. Neutra’s Kaufmann House—built for the same man who’d commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater in Pennsylvania—was built in 1946.

Neutra stole at least one of my friend the great California architect Cliff May’s central ideas: the place is built around a courtyard and includes a fair amount of natural materials—the stone walls and chimney came from nearby quarries and match up with the colors of the adjacent San Jacinto Mountains. And Neutra went with an early version of xeriscaping, as he filled the front yard with large boulders and desert plants that didn’t need much water.

Neutra’s success in Palm Springs brought more commissions, and more modernist architects followed in his wake, although few of them had Neutra’s dominating personality. “I am not International Style,” he once said. “I am Neutra!” It wasn’t long before John Lautner, Albert Frey, and Rudolph Schindler were building there as well. The result was that Palm Springs became a hotbed of modified Bauhaus aesthetics. But when I was first going there, most of the architecture was Mexican or Spanish villas.

In the ’60s, the houses were open in design, with air-conditioning—Palm Springs could never have been settled in a large way without the invention of air-conditioning—and windows that made the desert landscape part of the dwelling.

I remember the Palm Springs of my youth as something out of a western movie or, more specifically, a dude ranch. It was very western; hotel employees dressed up as if they were the Sons of the Pioneers, in embroidered shirts and cowboy boots. The bartender at the Racquet Club was actually named Tex. Tex, the lawyer Greg Bautzer, and I once got into a big fight at the Racquet Club with a couple of obnoxious out-of-town drunks. Tex could not only mix a killer martini, he could also clean out a room, and quickly.

The important thing to note about Palm Springs is that it was actually a small town, an intimate place whose population was mostly an extension of Hollywood.

There was, for instance, Alan Ladd Hardware, which I suspect had been started by Ladd or his wife Sue Carol as a hedge against the vagaries of the movie business. It was actually a spectacularly well-stocked and successful store, and it was there for a long, long time. And I still remember Desmond’s department store.

Among the other celebrities who lived in Palm Springs were Zane Grey, Sam Goldwyn, the composer Frederick Loewe, Dinah Shore, and Frank Sinatra. William Powell and his much younger wife Diana Lewis—everybody called her “Mousie”—had moved there after he retired, and I got to know him well.

As you might expect, Bill Powell was a gentleman. He was a good drinking man, and surprisingly self-effacing. One time I complimented him on the marvelous series of movies he had made with Myrna Loy and the qualities he had brought to all of his films, but he didn’t seem to think they, or he, were all that much.

Yours truly having a good time at a party in Palm Springs, circa 1955.

Everett Collection

“I never really did anything different,” he said, referring to his career. I thought he was being unfair to himself, and still do.

In the 1950s, Palm Springs began to change. When I first went there with my father, it had precisely one golf course: the O’Donnell, a little nine-holer. But soon other courses sprang up—Thunderbird, Tamarisk—and later the Eisenhower Medical Center changed the nature of the town. It became far more of a retirement community than it ever had been, and the geriatric influence shifted the nature of the town—it became less exuberant, more sedate. At the same time, it also became less seasonal and more of a year-round place.

Frank Sinatra started out by buying a little three-bedroom tract house near the Tamarisk Country Club and began remodeling and adding on until he had a very large compound with guesthouses, a helicopter pad, and a caboose that held his huge model train layout—Frank loved his Lionel trains. Next door to his own compound, he built a house for his mother, Dolly. Down the street Walter Annenberg had a private golf course.

For years, we would go to Frank’s for New Year’s Eve. Dean Martin would be there, as would Sammy Davis Jr., perhaps Angie Dickinson. Frank appreciated the remoteness of Palm Springs but also liked the fact that the place wasn’t so remote he’d be deprived of the amenities he wanted. By the time he was finished with the house, it had a walk-in freezer and a huge dining room that sat twenty-four people. The interior decoration made some of the place look like a luxurious modern hotel, but I always figured that was because Frank had spent so much of his life in hotels that it was the kind of environment in which he felt comfortable.

Eventually I moved to Palm Springs, too, when I married my second wife, Marion, in the early 1960s, and my kids went to school there. We lived there for seven years—seven very happy years. My house was built out of desert rock and was Spanish in design—Herman Wouk lives there now. That house was just a bit away from the house that had been built by Zane Grey, and it was right across the street from one of King Gillette’s houses.

My proximity to Zane Grey’s house was thrilling to me. I’d read his novels as a boy, and knew he’d been a great outdoorsman who had done a great deal to popularize deep-sea fishing. It always delighted me to think how we could have been neighbors if Grey hadn’t gone and died.

My future wife, Jill, and Frank at the very first Frank Sinatra Golf Tournament in Palm Springs, circa 1960.

Lester Nehamkin/mptimages.com

When Natalie and I married for the second time, in 1972, I still had the house, and we decided to settle there. We added some rooms on, and when our daughter, Courtney, was born, we raised her there. Then we bought our house in Beverly Hills from Patti Page.

There were other places where people went to get away, some of them pretty far afield. Gamblers often went over the border to Tijuana, Agua Caliente, and Ensenada. It’s an open question who was the biggest gambler in Hollywood, the answer known only to accountants of the period. I’d put my money on either David O. Selznick or Joe Schenck, the latter of whom actually had a casino in his house, although when the police closed it down Joe claimed he didn’t know about it.

Uh-huh.

Then there was Harry Cohn, founder of Columbia Pictures. Cohn’s annual one-month vacation took place at Saratoga Race Course, and he is said to have averaged five thousand to ten thousand dollars a day in bets. This went on until he hit a cold streak and lost four hundred thousand dollars.

A normal man might have had a nervous breakdown over losing that amount of money—I know I would. In fact, Cohn’s brother, a cofounder of the studio, had to warn him that he would be removed from the presidency of Columbia Pictures if he didn’t get his gambling under control.

So Harry Cohn slowly put aside horses in favor of betting on football, and cut back to betting only about fifty dollars on college games.

It makes perfect sense that many of the moguls were, in fact, serious gamblers, because spending millions of dollars on a movie is nothing if not a gamble. B. P. Schulberg, who ran Paramount in the early 1930s, was a particularly degenerate gambler, and it ruined his career. There were quiet poker games around town as well, and people like Eddie Mannix, Joe Schenck, Sid Grauman, Norman Krasna, and the Selznick brothers were regular participants. A lot of money changed hands on these outings; the story goes that B. P. Schulberg once dropped a hundred thousand dollars in one night—and this at a time when a hundred thousand dollars was serious money, even in Hollywood. The Selznicks came by their habit naturally; their father had ruined his business by gambling.

Interestingly, almost all of the town’s serious bettors were men; of the women, only Constance Bennett is said to have been able to hold her own at the poker tables. Clifton Webb told me that whoever was hosting the game would bank the money the next morning—nobody wanted to walk around with hundreds of thousands of dollars—and checks would be handed out later that day.

I was close friends with Connie Bennett’s husband Gilbert Roland, with whom I worked in Beneath the 12-Mile Reef. It seems that one night Gil lost fifty thousand dollars at the poker game. The problem was that Gil didn’t have fifty thousand dollars, or anything even close to it, so Connie had to make the debt good. As she handed over the check, she said, “Oh, the fucking I’m getting for the fucking I’m getting.”

Gil was a spectacular-looking man, very passionate, extremely romantic. He would talk about his remarkable history with women, but not in a graphic way. Women meant a great deal to him; life meant a great deal to him.

Gambling has always been one of the main participatory sports in Hollywood, always illegal, often tolerated, usually thriving. In The Big Sleep Raymond Chandler wrote about a place called the Cypress Club, a barely disguised version of the Clover Club, which was above the Sunset Strip, just west of the Chateau Marmont.

Opened in 1933, the Clover Club was the creation of Billy Wilkerson, director Raoul Walsh, and Al and Lew Wertheimer. The only way to gain entrance to the Clover Club was through membership—i.e., money—or if they knew you.

The food was excellent at the Clover Club, but the main attraction was gambling. The Clover Club, along with other, less renowned venues, were variations on the speakeasies that had thrived during Prohibition.

It was surprising how well known these places were, even though they were ostensibly illegal. Radio broadcasts featured them. The newspapers covered them as well, noting that such people as David Selznick and Gregory Ratoff—also a heavy gambler—were patronizing the Clover Club. Some clubs even advertised, usually using the word “exclusive” in the copy. When the Clover closed, Lew Wertheimer went on the payroll at Fox because Joe Schenck was into him for serious money. The Fox stockholders helped him pay it off.

Then there were the gambling ships moored just beyond the three-mile limit. One of them was the Tango, which began operating off Venice Beach in 1929 and was still there ten years later. The Johanna Smith billed itself as “the world’s most famous gambling ship.” But the one that seemed the most heavily patronized was the Rex, which was moored off Santa Monica for years, in full view of shore. To ferry people out to the Rex, there were three barges and a fleet of water taxis. The ads in the newspapers announced:

Only 10 minutes from Hollywood, plus a comfortable 10-minute boat ride to the REX.

25 cents round trip from Santa Monica pier at foot of Colorado Street, Santa Monica.

Ship opens at 12:30 p.m. daily.

From the way the ships were presented, you would have thought you were boarding the Queen Mary. Actually, the Rex was a converted fishing barge that looked . . . like a converted fishing barge, even though an ex-con named Tony Cornero had spent a quarter million dollars to convert it. But its unlovely appearance was much less important than what happened on board.

The ship itself had a 250-foot glass-covered gaming deck offering faro, roulette, and craps. Everybody’s gambling tastes could be accommodated, from high rollers to the penny ante. There were three hundred slot machines, a bingo parlor that seated five hundred people, six roulette tables, eight dice tables, keno. . . . There was even a complicated setup for offtrack betting. On a lower deck there was dancing and entertainment, a café, and several bars.

The Rex could accommodate two thousand customers, and its daily profit could be as much as ten thousand dollars. To keep their profits safe from bandits, the boat was heavily fortified by security with a generous supply of machine guns.

Soon the waters off the California coast were dotted by gambling ships hovering outside the three-mile limit: the Monte Carlo, the City of Panama, the Texas, the Showboat, the Caliente. One ship, the Playa, wasn’t satisfied with the three-mile limit, and sailed twelve miles out, which was not only beyond Los Angeles County jurisdiction but beyond federal jurisdiction. The Playa served out-of-season food that was forbidden on land—elaborate stuff, but great stuff. In order to get people onto those boats, they hustled everybody and everything.

Supposedly law enforcement personnel were very frustrated by the presence of the Rex and the rest of the ships, but I don’t believe it. None of the many underground enticements of Los Angeles before and after World War II would have been possible without the apathy of or, more likely, the acquiescence of the police. The amount of payoffs from the gambling houses of Los Angeles and Hollywood that padded the pockets of the cops must have been nearly equivalent to their profits. It was an environment that spawned a lot of James Ellroy novels.

The gambling ships came to an end just before World War II, when California attorney general Earl Warren got serious and went after them, using as a wedge the fact that the water taxis that ferried the customers back and forth weren’t registered as public vehicles.

Only a few years later Las Vegas was born out of an effort to service the gamblers of Los Angeles.

But before Vegas there was Agua Caliente, a resort just across the Mexican border built for the specific purpose of enabling Americans to indulge in the pleasurable activity that was forbidden in their native country: gambling.

Agua Caliente was the brainchild of Baron Long, a man who ran gambling and bootlegging outfits around Los Angeles, usually skirting the law by operating just outside the city limits in unincorporated towns like Vernon or beyond the three-mile limit at sea.

In 1926 Long decided to take advantage of the “anything goes” atmosphere of Mexico and build a spa at Agua Caliente Hot Springs, six miles from Tijuana. There was no shortage of investors; I believe some of the original generation of movie moguls, such as Joe Schenck, came in on the deal. Joe supposedly spent something close to half a million dollars building the resort and casino.

Joe Schenck was such an interesting man. He and his brother Nick controlled three movie studios: Nick ran Loew’s Incorporated, the parent company of MGM, while Joe, after a very successful career as an independent producer, first ran United Artists, then left to form 20th Century pictures with Darryl Zanuck, which soon took over the moribund Fox organization and became 20th Century Fox—the studio that signed me in 1949.

The resort’s grounds didn’t look like much originally—just scrub with sycamore trees—but by the time it opened in June 1928, after millions of dollars in construction costs, the landscape had been radically altered. Occupying 655 acres, it even had its own airport, with easier access for those long weekends. It was an immediate success, because it was the only game out of town. If you wanted the types of things Agua Caliente offered, you had to go to Agua Caliente.

The centerpiece of the resort was a four-hundred-room luxury hotel. Well, that’s not really true—the centerpiece was the casino, where roulette, baccarat, and faro were played. And after the casino came the racetrack. The racetrack attracted people who wouldn’t be caught dead in a casino—Gary Cooper was there, as were Bing Crosby and Clark Gable, Jean Harlow and Howard Hughes.

Occasionally, a film would shoot there—the location was visually interesting, and there were plenty of ways to pass the time at night. When Jackie Cooper goes hunting for his alcoholic father around a luxury hotel in The Champ, he’s searching Agua Caliente. There was even a Warner Bros. movie called In Caliente, featuring the great Busby Berkeley number “The Lady in Red.”

While the hotel’s exterior looked like something left over from the mission days, inside it was another story entirely. There was an Art Deco dining room inspired by the 1925 Paris exhibition, plus a Moorish-style spa and a Louis XIV–inspired room.

It was the height of a certain kind of luxury. Even the barbershop, which had only three chairs, flaunted custom-designed terra-cotta. The power plant had a 150-foot-high smokestack that was tiled and covered with decorative ironwork so that it resembled an Istanbul minaret.

So much of what would make Vegas Vegas was actually devised at Agua Caliente. Food, for instance, was a loss leader—they charged only a dollar for a sumptuous lunch, and the casino was without clocks or windows. Sound familiar?

Agua Caliente did not set out to compete with Palm Springs or Catalina; it was designed to attract the same clientele as the Riviera or Palm Beach. And for a time, it succeeded. Movie people loved it. Aside from Joe Schenck, other shareholders included Al Jolson, Irving Berlin, and Alexander Pantages. In 1933, Schenck purchased control of the resort and positioned himself on the board of directors, along with Douglas Fairbanks Sr. and Jesse Lasky.

And then it all came crashing down. In 1935 the president of Mexico signed an executive order outlawing gambling. Two days later, the resort shut down.

Conveniently, just a few years earlier, Nevada had passed legislation allowing gambling, which meant that it was just a question of time until everything that made Caliente Caliente would be available without having to cross the border. Mexico eventually nationalized the old resort and used it as an education facility, although three fires in the 1960s and a misguided urban renewal program in 1975 wiped out the facility as a whole. But for a few years, Caliente was the site of a gaudy spree that eventually landed close to home.