Billy Wilder could do a lot of things, and setting a scene was one of them.

“I had landed myself in the driveway of some big mansion that looked run-down and deserted,” says William Holden as Joe Gillis at the opening of Sunset Boulevard. “It was a great big white elephant of a place. The kind crazy movie people built in the crazy twenties.”

Billy’s attitude was typical. The rap against the architecture of Los Angeles was that it was nothing but a conglomeration of warring styles. But that’s because Los Angeles had a very small indigenous population; it was settled by people who streamed there before and after World War I. All these new arrivals were from different parts of the world and all of them had different ideas of taste; with the exception of the Mission style that was the legacy of Spanish California, there was no strong architectural tradition to guide a building boom.

Initially the movie people settled in and around Hollywood Boulevard, and the bungalows that had been part of the initial settlement around 1900 were replaced by the Spanish Mediterranean look that became the first wave of popular style.

There were also apartments that catered to the movie people who were holding on to their money to see whether this movie thing had any permanence. A lot of them were built around courtyards, with fountains and Spanish tile. Of these, the most elaborate was the Garden Court, which stood on Hollywood Boulevard into the 1970s. Sixty years earlier the Garden Court had refused to take people from the movie industry, with very few exceptions, such as the very proper Englishman J. Stuart Blackton, who founded the early motion picture firm Vitagraph.

But if blame is to be apportioned for what Beverly Hills is today, it should probably go to Douglas Fairbanks.

In the beginning, Beverly Hills was all beans, acres of beans, and the only people who lived there were Mexican migrant workers. But after 1900, oil was discovered in what would become West Hollywood and land began changing hands. The land was now too valuable to be relegated to farmland, so it was divided up into residential lots.

To do the landscaping and planning, the landscape architect Wilbur Cook Jr. was hired. Cook had worked on the design of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago alongside Frederick Law Olmsted, who was famed for his design of New York’s Central Park.

Cook laid out a three-tier system. People without a lot of money were relegated to small lots in the area around Wilshire and Santa Monica Boulevards. The area of Beverly Hills that lay “below the tracks” of the Pacific Electric railroad along Santa Monica Boulevard came with restrictive covenants that forbade blacks or Asians from buying, owning, or even residing there except as live-in servants. Cook also made space for a commercial zone that was close to the large houses and estates to the north.

North of Santa Monica and south of Sunset was for the upper middle class, with large houses, wide lots, and streets lined with trees of identical size and species. (These guys left nothing to chance.) The hills above Sunset Boulevard were reserved for mansions.

What Cook wanted to avoid was a grid plan of straight lines and squares, which would inevitably lead to views of empty fields extending toward the ocean. What he designed were largely curving streets, which led to a procession of constantly changing views. He used garden hoses to mark off the curves of the streets, forming the borders of the roads. The curves created a feeling of coziness, of community.

The first lots went on sale for eight hundred to a thousand dollars an acre, with a 10 percent discount if paid in cash and another 10 percent discount if construction started within a year. The original streets were Rodeo, Beverly, Canon, and Crescent Drives. Beverly Park sat between Beverly and Canon, which had a beautiful koi pond and a sign announcing that you were now in Beverly Hills—as if there could be any doubt.

For a long time, Beverly Hills remained quite barren because most of the movie people were still living around Hollywood proper, or in Crescent Heights or Los Feliz. Seeing that lots weren’t moving, a developer named Burton Green figured that a hotel might stimulate a land rush. (For many years, it was believed that Green had named the town after Beverly Farms, his home in Massachusetts, but that’s not true. Green’s own version of the naming of Beverly Hills is as follows: “I happened to read a newspaper article which mentioned that President [William Howard] Taft was vacationing in Beverly, Massachusetts . . . It struck me that Beverly was a pretty name. I suggested the name ‘Beverly Hills’ to my associates; they liked it, and the name was accepted.” Given the natural beauty of the location, they could have called it Hogwarts and it probably would have been successful.)

In early February 1911, Green hired Margaret Anderson and her son to open and operate a luxury hotel.

Margaret had originally come to California in the 1870s. She’d married, had two children, and worked in the orange business. After a nasty divorce, she took over a boardinghouse in Westlake, and in 1902 the Hollywood Hotel. So Margaret and her son Stanley were Hollywood pioneers, the hospitality equivalent of Cecil B. DeMille.

Margaret’s motto was “Our guests are entitled to the best of everything, regardless of cost.” In the early days the Hollywood Hotel had forty rooms. The hotel cost—wait for it!—the munificent sum of twenty-five thousand dollars, and was designed by Oliver Perry Dennis and Lyman Farwell, who also designed the building that would become the Magic Castle in Hollywood. The Magic Castle is still standing; I wish I could say the same for the Hollywood Hotel.

Two people could stay at the hotel for $32.50 a week. For that money, you also got a private bath and all your meals—a bargain. While his mother ran the hotel, Stanley took on a leadership role in the community at large—first in Hollywood, later in Beverly Hills. Stanley knew everybody, was friends with everybody: industrialists, entrepreneurs, and, of course, celebrities. He also began dabbling in real estate, buying property on Rodeo Drive. Stanley’s son once expounded to me about his father’s wisdom in buying retail corner lots. Unfortunately, I never took the advice to heart.

Construction of the Hollywood Hotel, circa 1905.

When Burton Green had the idea for the Beverly Hills Hotel, the obvious choice to run it was Margaret Anderson and her son.

Photos taken during construction in 1911 show nothing much there other than a huge, flat, open field and a water wagon for the workers.

The hotel itself was built to resemble a Franciscan mission, with a white stucco exterior and terra-cotta Spanish tile roof. The original promotional brochure laid it all out in the soothing tones beloved of advertising travel writers since the beginning of time: “Every time one thinks of California he thinks of sunny romance and gold; of sunny skies and balmy breezes; of whispering palms and sandy beaches and gently booming surf. He thinks of climate the like of which is not equaled in any other part of the world. . . . Here in Southern California’s most entrancing spot on the main road halfway between Los Angeles and the Sea is the Beverly Hills Hotel.”

On the day it opened in 1912, Green’s investment totaled half a million dollars—a huge sum in 1912. It was generally felt that the hotel was so far off the beaten track that it was sure to fail, but it quickly became quite popular, helped along by a Pacific Electric trolley line that stopped directly in front of the entrance. Thus, travelers could get off the train in Los Angeles and travel to the hotel with a minimum of fuss. But home sales still lagged in the area, and for a good ten years after it was constructed, the Beverly Hills Hotel continued to look out on nothing but empty fields.

The hotel soon became famous for its gardens, which certainly figured to attract Midwesterners from the frigid plains of Iowa and Kansas. Stanley devised a brilliant publicity strategy: the patrons of the hotel were encouraged to pick any of the flowers that grew in the gardens. Arranged in bouquets in the rooms, the flowers added a personal touch that made the guests feel right at home.

The hotel began building bungalows in 1915, which indicates that they were getting patronage from people who wanted to stay for the entire winter and for whom a hotel room would be too confining. The first five bungalows were in the Mission Revival style and had several bedrooms apiece—bring the entire family!—and a porch overlooking the main court of the hotel. By the 1930s, there would be more than twenty bungalows, scattered over the sixteen acres of gardens.

In 1915 among the amenities on offer were horseback rides before breakfast with a stable of Kentucky horses on the grounds. Then there was golf at the adjacent Los Angeles Country Club. And believe it or not, there were fox hunts in the hills above the hotel, which tells you a lot about the guests who stayed there.

In 1919 Douglas Fairbanks, the first great swashbuckling star of the movies and as charismatic a man as ever walked in front of a camera, bought a glorified hunting lodge on Summit Drive, off Benedict Canyon, about a half mile above the Beverly Hills Hotel. He paid thirty-five thousand dollars for the place, and it wasn’t much—it had six rooms, no electricity, no running water, and looked a little run-down.

And then it got worse. As Stanley Anderson’s son told me the story a quarter century later, the morning after Fairbanks moved in, Stanley’s phone rang. It was Fairbanks, and he was distraught. “I’ve never felt so awful,” he said. “I have to leave Beverly Hills.” It seemed that three of his new neighbors had called him the night before and told him that actors weren’t welcome in the town. Property values, and so forth.

Stanley happened to know the neighbors in question—Stanley knew everybody. First he managed to calm Fairbanks down; then he defused the situation by calming the neighbors down. Fairbanks decided to stay and began remodeling and greatly enlarging the old lodge. Soon afterward he married Mary Pickford. It was a royal wedding, for Pickford was Fairbanks’s opposite number: the King of Hollywood was marrying its queen.

Like almost all the early stars, Pickford was born poor. Her father had died young, and the only way the Toronto family could survive was for Mary—whose real name was Gladys Smith—to go onstage. She was very blond and very beautiful, and she became quite successful as a child actress, eventually going to work for the famous theatrical producer David Belasco. That led to work with D. W. Griffith at the Biograph studio on the Lower East Side of New York, which in turn led to a twenty-year career of success in the movies.

Pickford and Fairbanks owned their own studios, owned their own films, and, along with Charlie Chaplin and D. W. Griffith, founded United Artists. They were all early examples of the actor as entrepreneur, and they set a pattern that the most ambitious stars replicate even today.

Chaplin and Fairbanks were best friends, and it was because of Fairbanks that Charlie Chaplin also built a house on Summit Drive in Beverly Hills in 1921. It certainly wasn’t because he was in love with the surrounding environment: “The alkali and the sagebrush gave off an odorous, sour tang that made the throat dry and the nostrils smart,” wrote Chaplin in his memoirs. “In those days, Beverly Hills looked like an abandoned real estate development. Sidewalks ran along and disappeared into open fields and lampposts with white globes adorning empty streets; most of the globes were missing, shot off by passing revelers from roadhouses.”

At night, Chaplin could hear the coyotes howling. Here was a poor boy from London who shuddered at the very thought of coyotes, but to Fairbanks it was all impossibly romantic. So Chaplin stayed.

After they married, Fairbanks and Pickford added another wing to the house and a second floor, and they ripped out most of the interior walls. Fairbanks’s plans were as grand as his movies, and he grew restless because the process was taking so long. So he moved in lights from his movie studio and hired enough workers for three eight-hour shifts. Fairbanks also landscaped the property beautifully, with hundreds of trees and shrubs, and added a swimming pool complete with a miniature sandy beach. Below the house was a stable that held six horses.

Christening their new home Pickfair, the couple moved in, and the world began beating a path to Beverly Hills. The house was decorated in a sedate style—the carpeting in Pickford’s bedroom was a pale green, as were the silk curtains, while the dining room had a beamed ceiling, watered silk wallpaper, and a sideboard that held a good silver tea service.

The hall next to the living room had a beautiful terra-cotta tile floor for dancing, and the pale green of the bedroom was replicated in the living room, which had accents of yellow drapes, a couple of antique vases converted into lamps, and a nice Oriental rug over the hardwood floor.

A lot of the furniture—all dark wood and heavily carved—came from Los Angeles department stores. Eventually, the house was redecorated in a more eighteenth-century French tradition, although Fairbanks’s enthusiasms virtually define the word “eclectic.” He spent a good deal of money on Frederic Remington paintings. Once he paid five thousand dollars—a fortune at the time—for a prize German shepherd, and was probably the first American movie star to develop a passion for English tailoring, about which more later.

Unfortunately, parties at Pickfair could be a trifle sedate—Fairbanks didn’t drink, and didn’t want anyone else to drink, either, perhaps because his own father had been a drunk, perhaps because he was worried about the long history of alcoholism in his wife’s family, which eventually afflicted Mary—the great tragedy of both their lives.

In those early years Fairbanks was quite the scamp. Frank Case, who ran the Algonquin Hotel in New York and knew a thing or two about the hospitality business, was a good friend of Fairbanks’s, and told some stories that demonstrated both the star’s boyish exuberance and how empty Beverly Hills was at the time.

According to Case, Fairbanks would climb into his Stutz Bearcat, shift into neutral, coast all the way down Summit Drive, and make it to the studio on Sunset and Vine without ever having to actually start his car. Occasionally, if he got bored, he’d skip the roads and cut across empty fields. Once, Fairbanks suggested that he might run alongside the car instead of sitting in it, just to keep things interesting.

These two people, both born into the lower middle class, became the hosts for kings and queens of Europe—Lord and Lady Mountbatten honeymooned at Pickfair, and every year a procession of dukes and duchesses descended to visit their dear friends Douglas and Mary. At other times they hosted Albert Einstein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Babe Ruth, and H. G. Wells.

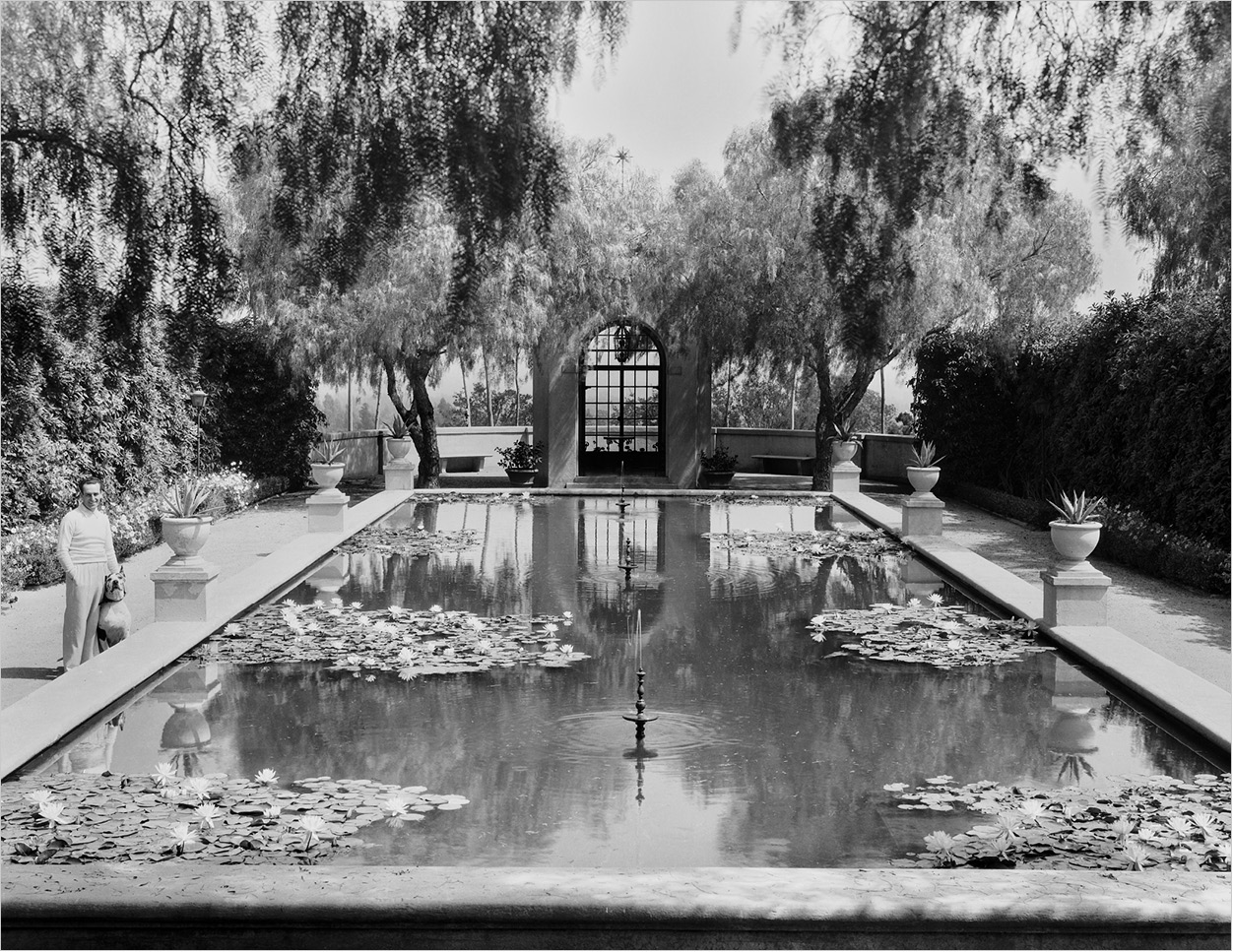

Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford in their swimming pool at Pickfair.

Getty Images

By greeting royalty as equals, they became royalty themselves, and some of that trickled down to the rest of Hollywood.

If I’ve spent a lot of time on Pickfair, it’s a measure not only of the eminence of its owners, but of the formal yet approachable country gentleman style of the house, which became a sort of model for Beverly Hills, and for many of the developments that followed down through the years. Fairbanks and Pickford themselves set the example for world-class movie stars as they lived their lives with a stately dignity.

Chaplin lived at 1085 Summit Drive for the next thirty years, until he left America for Switzerland. Mary Pickford remained at Pickfair until her death in 1979. Douglas Fairbanks died in 1939, so I never met him, which I regret—he was a golf fanatic, so we would have had plenty to talk about.

After Doug and Mary, other stars followed. The area was now officially open for movie business, and the lawns and gardens of the Beverly Hills Hotel were frequently used for locations. Harold Lloyd, who would become a close friend and mentor of mine, would shoot scenes from his film A Sailor-Made Man there in 1921, and Charlie Chaplin would make The Idle Class right across the street, in Sunset Park.

The movie studios themselves soon followed. In 1925 William Fox bought 108 acres on the western border of Beverly Hills. His studio had been located at Sunset and Western in Hollywood since 1915, but Fox was an expansion-minded man and needed more space. Three years later he christened Fox Movietone Studios.

King Gillette, the founder of the shaving company, sold his first Hollywood house to Gloria Swanson, then commissioned a beautiful Spanish Colonial Revival house in Malibu Canyon from Wallace Neff.

The Gillette/Swanson house was at 904 North Crescent Drive, just north of Sunset and across the street from the main entrance to the Beverly Hills Hotel. It was a modest little cottage—115 feet wide and 100 feet deep, with twenty rooms spread over four acres. There were five bathrooms and an electric elevator to take you to the second floor. There was also a thousand-square-foot terrace that overlooked the lawns and a sweeping garden of acacias and palm trees.

The walls were hung with tapestries and draped in peacock silks. The mistress’s bathroom was done in black marble with a golden tub. There was a movie theater and a large garden. When she entertained, butlers were dressed in full livery. Swanson was all of twenty years old when she bought the place from Gillette in 1919, and she was evidently seeking to replicate the swanky society dramas she was making for Cecil B. DeMille.

It was a dream palace, different from Pickfair, but equivalent in terms of its impact.

After Fairbanks and Chaplin built on the street, Tom Mix started construction on his own six-acre estate, at 1018 Summit Drive. It had a wall around the property by the side of the road, so you couldn’t see too much of it, but you could always tell it was Tom Mix’s house—there was a large neon sign mounted on the roof that flashed the letters “TM” to the night sky.

Beverly Hills construction skyrocketed 1,000 percent within five years. Will Rogers was named honorary mayor of the town, and in his inauguration speech he announced the prevailing ethic, which would define show business: “I am for the common people, and as Beverly Hills has no common people, I’ll be sure to make good.” He then promised to give the city’s nonexistent poor bigger swimming pools and wider bridle paths.

A house that was almost equal in fame to Pickfair belonged to Rudolph Valentino. Falcon Lair was located off Benedict Canyon Drive, past Summit Drive, at 1436 Bella Drive (now Cielo Drive). Falcon Lair was aptly named, because it was situated on eight acres on a promontory below which you could see the sparse (at the time) lights of the city below. Valentino paid $175,000 for the house and property in 1925, and was so compulsive about spending that he had only enough money for the down payment. He asked Joe Schenck, to whom he was under contract, for help in buying the place, because its owner didn’t want to accept the actor’s personal note—for good reasons, as it turned out. Joe was an obliging man, so he cosigned the loan. Valentino would live in it for a little more than a year before his sudden early death. But in that year he spent a huge amount of money he didn’t have, redecorating the main house, putting up a nine-foot taupe wall around the property, building stables and kennels, and adding servants’ quarters over the garage.

Falcon Lair was Spanish in style, with a red tile roof and stucco walls that were also painted taupe. The house was decorated rather like a set from one of Valentino’s own larger-than-life romantic movies. The doors were imported from Florence, and there was a life-size portrait of the owner dressed in the costume of a Saracen warlord from the Crusades. The floor in the entry hall was travertine. The drapes were all of Genovese velvet, and the curtains in the master bedrooms were hand-loomed Italian net.

The house was primarily decorated with antiques—Turkish Arabian, Spanish screens, Florentine chairs, a French walnut chest from the fifteenth century. Valentino had thousands of books, and there were weapons and armor scattered throughout the house.

If all you saw were the main rooms, you might think the place looked like a museum of medieval artifacts. But in his bedroom Valentino indulged himself with an exotic range of colors. The king-size bed had gold ball feet, while the headboard was lacquered a dark blue. The sheets, pillowcases, and bedspread were crocus yellow, as were his Japanese silk pajamas. There was an orange lacquer pedestal table at the foot of the bed that had a perfume lamp on it—when the lamp was turned on, the room would fill with fragrance.

A rear view of Rudolph Valentino’s Hollywood home, Falcon Lair, which was built into the side of a high hill. Notice the aviary at bottom left.

Bettmann/CORBIS

The interesting thing about Falcon Lair was that the rooms were actually rather small. My wife Jill shot a movie there about ten years ago, and she walked around the house and grounds during the shoot, surprised at its modest scale. As she put it, “It was not a mansion; it was a very comfortable large house.” Valentino’s taste for ornate decoration made the place feel slightly crowded. On top of his taste in décor, he filled his closets with clothes—thirty business suits, ten dress suits, four riding outfits, ten overcoats, thirty-seven vests, a hundred twenty-four shirts, and on and on. His jewelry box contained thirty rings.

Falcon Lair also came equipped with all the extras—there was a stable for Valentino’s four Arabian horses and a kennel for his Great Danes, Italian mastiffs, and greyhounds.

It sounds colorful and over-the-top gorgeous, but that was typical of the time. (Unfortunately, there are no surviving color photographs of the house.) Whatever their particular style, in this period and for the next quarter century it was the detailing—the materials that are often considered of peripheral importance, such as brass fittings, parchment, walnut veneers, wallpaper imported from China, whatever—that made Hollywood houses special.

It was a sybaritic environment that would have seemed over-the-top for Norma Desmond, but Valentino himself was an odd combination of aesthete and auto mechanic. His greatest pleasure, besides riding horses or playing with the dogs, involved stripping and reassembling car engines and transmissions. I’ve always thought that the house and its decoration must have involved a sense of performance for Valentino, but I would see that in a number of the great houses I would visit.

Valentino was making good money at this point in his life—Joe Schenck was paying him a hundred grand per picture plus a percentage of the profits (and this was in the mid-1920s!)—but there was no way he wasn’t outspending his income by a factor of three or four.

When Valentino died of peritonitis in August 1926, he was deeply in debt. It was thought that Falcon Lair would sell for somewhere between $140,000 and $175,000, with his possessions worth as much as $500,000. In other words, the best-case scenario was that the house would be worth about half of what Valentino had invested in the place. If the estate hadn’t been so far in the hole, it would have made sense to wait, but Valentino couldn’t afford to.

When the estate auction was held, Valentino’s possessions brought less than $100,000, and the house itself didn’t sell at all. Finally, in 1934 an architect bought it for the minute sum of $18,000. Eventually, Doris Duke bought the house, but seldom lived in it. The majority of Falcon Lair was torn down in 2006.

The years between 1925 and the stock market crash in 1929 constituted a housing free-for-all in Beverly Hills. Spanish haciendas were built, as well as Arabian mosques, French châteaux, pueblo-inspired homes. There were even some Tudor mansions. Whatever the varying exterior styles, though, most of these houses were very modern inside, with French doors common so as to enable easy flow between indoors and the mild California outdoors.

Just as Joe Schenck had cosigned a house loan for Valentino, so Louis B. Mayer gave Joan Crawford an advance so she could buy a house on North Roxbury in Beverly Hills. The moguls thought that such loans were a good investment in rising stars they believed in, and might also provoke a feeling of gratitude that could only work to the studio’s advantage. A few years later, in 1929, Crawford was an even bigger star, so Mayer OK’d a loan of forty thousand dollars so she could buy a ten-room mansion at 426 North Bristol Circle in Brentwood.

Crawford’s favorite room there was the sunroom, which had windows on three sides and shelves filled with dozens of dolls—Crawford had been a deprived child and saw no reason not to pamper herself with the things she hadn’t had when she was a little girl.

I heard Joan talking about how Billy Haines convinced her to get rid of her collection of hundreds of dolls and dozens of black velvet paintings of dancers. There was no way, he told her, that he could do anything to transform her house into a glamorous environment if she was going to cling to such junk. Joan valued class more than she did her collections, so she gave her dolls and paintings away.

All the prevalent architectural styles were replicated in the palatial movie theaters that were going up across the country. Some were designed as Moorish palaces with ceilings full of twinkling stars; others were Chinese, or Egyptian, but they were all wildly ornate, selling a fantasy that was way beyond the financial reach of 99 percent of the audience that flocked to them. Hollywood was embodying an oversize sense of scale that was an echo of the showmanship that was making the movies. The great sets of the silent era—Fairbanks’s castle for Robin Hood and his even vaster sets for his Arabian Nights fantasy The Thief of Bagdad—provided a creative impetus for people within the movie industry and fueled the fantasies of their audiences. Why have a house when you could have a castle?

Right about this time Los Angeles also saw a proliferation of buildings whose forms imitated their functions. A ten-foot-tall orange held an orange juice stand; a huge donut housed a donut shop. There was a place called the Tail of the Pup that looked like a hot dog encased in a bun—you can guess what they sold.

The building that always intrigued me was the Utter-McKinley Mortuary on Sunset and Horn. There was a large clock mounted on top of the building, but it had no hands. Beneath it was a sign that read “24-Hour Service.”

I always thought a clock without hands had a certain ominous “ask not for whom the bell tolls, it tolls for thee” significance that went far beyond undertakers, who never got a full night’s sleep.

Entrepreneurs such as Sid Grauman and Max Factor had their buildings designed to resemble movie sets, and as these buildings were displayed in movies and newsreels, their styles influenced other buildings all over the world, both for and against. It’s possible that without the glamorous excesses of buildings exemplified by Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, the subsequent and—to my mind—overly severe architecture of Mies van der Rohe might never have happened. I suspect that Hollywood’s use of dramatic, extreme architecture—and the public acceptance of it—made the world safe for the more daring architecture that later became the norm.

The studios themselves adopted the same veneer of showmanship. Some of them were more or less architecturally undistinguished factories, like Paramount. But the Chaplin studio on La Brea was built to resemble a string of Tudor cottages, and Thomas Ince’s studio in Culver City—later bought by Cecil B. DeMille and then by David Selznick—was a replica of George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

And let’s not overlook one of the enduring wonders of Los Angeles architecture: the Witch’s House, built to house the productions of silent film director Irvin Willat. Designed by art director Harry Oliver, it was originally in Culver City but was later moved to Beverly Hills, to the corner of Carmelita Avenue and Walden Drive. Even though it’s been a private residence for the last eighty years, it looks exactly like a set for Hansel and Gretel.

All of this exuberant eclecticism bothered the intellectuals, who thought it was vulgar. But Hollywood made its living manufacturing dreams. If it had looked like Newport, the dreams wouldn’t have cascaded over the world as successfully as they did.

And one other thing: these buildings were fun to look at. They were architecture as entertainment.

When Ramon Novarro opted for a tidy house designed by Lloyd Wright, the son of Frank Lloyd Wright, he had MGM art director Cedric Gibbons redecorate entirely in black and silver. Novarro fell so in love with the look that he would ask his dinner guests to comply with the prevailing design scheme and wear only black or silver to his parties.

Gibbons was a huge influence both within the industry and without. His designs for the 1928 Joan Crawford movie Our Dancing Daughters showcased Art Deco throughout and helped usher out the heavy Spanish décor. Deco became the look of the young moderns—clean lines and chic.

The movie was successful enough to spawn two sequels, the last of which costarred William Haines, who didn’t care for Gibbons’s aesthetic and stayed away from Deco when he became a fashionable designer. “It looks like someone had a nightmare while designing a church and tried to combine it with a Grauman theater,” he remarked.

In retrospect, there was a playful aspect to a lot of these houses, as if the actors, directors, and producers were extending the fantasies they created on-screen into their private lives. The houses were partly sets, partly playgrounds—literally.

Many people saw the beautiful sets designed by Cedric Gibbons at MGM or Van Nest Polglase at RKO and asked them to design their houses. Ginger Rogers had a house off Coldwater Canyon that was largely the work of Polglase. Gibbons’s own house, which he designed and built for his marriage to Dolores del Río, was a stunning Moderne masterpiece. Likewise, the art director Harold Grieve, who was married to Jetta Goudal, a star for DeMille in the silent days, developed a business in interior decoration that far surpassed his work for the studios.

By 1937, when I arrived, when you got off the Pacific Electric line in Beverly Hills, nobody noticed the unpaved roads above Sunset, or the bean fields in the flats, or the modest shopping district. Everybody was mesmerized by the vastness of the homes.

When the stock market collapsed in 1929 and the Depression ensued, construction in Los Angeles also collapsed. Construction of new houses and apartments fell from 15,234 in 1929 to 6,600 in 1931. Luxury housing went into a decline, but there were plenty of available places, as silent film people who lost their footing in sound pictures had to downsize. Many of the new stars of the sound era bought secondhand homes instead of building their own, although there were exceptions. William Powell built a house with a complicated series of features that emerged from walls and rose from the floor. A bar turned into a barbecue by pushing a button; other buttons opened and closed doors. But the wiring was badly done, and there was a comic period when Powell would push a button to go into the parlor, but the kitchen door would open. The house had thirty-two rooms, and something unexpected would happen in each of them.

It would have made a great scene in a comedy starring Cary Grant—or Bill Powell—but Bill, understandably enough, didn’t think it was funny.

“Follow the money” is a brief but telling sentence that has been serving reporters well since the invention of movable type. And the way we lived in Hollywood provides yet another instance of following the money.

In 1941, shortly before I started caddying at the Bel Air Country Club, two thirds of all American families earned between one thousand and three thousand dollars a year. A further 27 percent had incomes of between five hundred and one thousand dollars.

By contrast, even a middling star could reliably expect to earn as much in a week as those two thirds of American families made in a year. A lot of people on the industry’s high end made many multiples of that.

So the houses, the resorts, the restaurants, the luxurious accoutrements that cluttered our lives were a direct result of the fact that, economically speaking, Hollywood wasn’t like the rest of America. Not even close.

By now many businessmen and dozens of movie stars had begun moving out of downtown Los Angeles and other old neighborhoods into the exciting nouveau riche air of Beverly Hills. Hollywood’s population exploded from 36,000 in 1920 to 157,000 in 1930 and would continue to grow, but it was no longer the chic place to live.

There was a slight gap in the styles of the era; there was no smooth transition between the lavish houses of the 1920s and the more streamlined architecture of the 1930s and ’40s, when architectural styles and interior decoration became noticeably less ornate and extravagant than they had been—the pendulum had swung in the opposite direction, as it always does. By the 1930s Spanish and Italian were out; neocolonial or, for particularly stylish people, Moderne, was in. One of the key transitional buildings was Union Station, which was built between 1934 and 1939, and is a beautiful example of both the Moderne and the Spanish styles—the former the new wave, the latter the old.

In this period you had Mediterranean Revival, but there were also opulent Italian Renaissance places such as Harold Lloyd’s Greenacres. And then there were the polyglot palaces. The director Fred Niblo had a Spanish mansion on Angelo Drive, high above Beverly Hills, but he couldn’t resist adding an English drawing room with paneling that was hundreds of years old. Period romance was all.

John Barrymore bought a comparatively modest house on Tower Road from King Vidor for fifty thousand dollars, then spent a million dollars over the next ten years on improvements. He bought an adjacent four acres, expanding the property to seven acres. He built an entirely separate Spanish house up the hill and connected the two houses with a grape arbor.

Being John Barrymore, he also had to indulge his eccentricities. Above his bedroom was a secret room that he could reach by a trapdoor and a ladder whenever he needed to get away from his family. By the entrance there was a totem pole painted red and yellow with a fern growing out of the top, like an uncombed head of hair.

By the time Barrymore was through with the project—actually, he just ran out of money—he had sixteen buildings and fifty-five rooms, with more buildings under construction. There was a skeet range, a bowling green, an aviary that held three hundred birds. It was like a little village on a mountaintop in Beverly Hills, all with red tile roofs and iron-grilled windows.

Barrymore couldn’t hold on to his money—none of the Barrymores could—and by 1937 he was being pursued by the IRS for back taxes and had to declare bankruptcy. The vast estate was put up for auction, but the place was such an extension of Barrymore’s idiosyncrasies and onetime income stream that no one bought it.

I never met John Barrymore, although I would have loved to have had the opportunity. I did have the good fortune to be friends with Harold Lloyd, whose house was similarly extravagant. Harold was a very special man. Greenacres, his Italian Renaissance mansion on Benedict Canyon Drive, covered twenty-two acres, forty rooms, and thirty-six thousand square feet—not counting the patios or porches.

Harold told me that by the time the house was finished in 1929, just in time for the stock market crash, he had spent two million dollars. The housewarming party began on a Friday and continued until Monday morning, with changes of bands every four hours to keep everybody energized.

Harold got what he paid for. The house had a seven-car garage and a splendid fountain by the entrance. In fact, it had twelve fountains, and you could hear the gurgling of water from practically every place on the property. The entrance hall itself was sixteen feet high, and there was a circular oak staircase attached to the wall without any supports beneath the risers.

Harold was particularly proud of his sunken living room, which had a coffered ceiling with gold leaf on it, elaborate paneling, and a forty-rank pipe organ for concerts or silent film accompaniment. The dining room could sit up to twenty-four guests, and the house carried a staff of thirty-two, sixteen of whom were gardeners. If you didn’t want to take the stairs, an elevator could convey you to the second floor, which held ten bedrooms.

Outside, Harold built a nine-hole golf course and an Olympic-size swimming pool. There were tennis courts and handball courts and even an eight-hundred-foot-long canoe lake adjacent to the golf course. For his three children, he also built a child-size four-room cottage with a thatched roof, complete with electricity, plumbing, and miniature furniture.

Harold Lloyd in the garden of Greenacres, his palatial Spanish-style villa in Beverly Hills.

Getty Images

All the furniture in the house was custom made, but Harold was from a small town in Nebraska and, believe it or not, was far from a spendthrift. Harold had a sunroom that had trompe l’oeil vines painted on the walls. The painter did a great job on the vines, and they looked quite lifelike. But he was very slow, and after a year or two the vines were still in progress. One day Harold had had enough and he told the painter he had exactly three weeks to finish the job. This explains why the small, carefully painted leaves suddenly got about five times as large in one corner of the room.

Me with Harold Lloyd’s daughter Gloria, at a costume party at Harold’s Palm Springs home.

Courtesy of the author

I met Harold Lloyd around 1948, when I began dating his daughter Gloria. Harold approved of the potential match, and I have to admit that his approval meant a great deal to me. At that point, Greenacres was only slightly more than twenty years old, but the upkeep on the place was huge, and Harold was no longer making a million dollars a year. He was economizing. The house had never been redecorated—the drapes were getting ragged, the furniture was frayed. Nothing had been replaced.

One year he got too busy to take down the Christmas tree, so there it stayed. Finally, he made up his mind to have a Christmas tree all year round, so each year he would install and structurally reinforce a fifteen-foot-tall tree, and then take two weeks to hang a thousand ornaments out of the ten thousand he owned. It was beautiful and eccentric—but mostly beautiful. I’m very proud that one of the ornaments on the tree was a gift from me. I also had an autographed picture in what Harold called his Rogues’ Gallery, a subterranean hallway lined with signed photos from everybody from Chaplin to DeMille.

Harold’s famous Christmas tree. I’m proud to say that somewhere in there is the ornament I gave him.

Harold was one of those men who had to be busy all the time. In most respects, he was a sweet man. He was passionate about photography, passionate about the movie business. Like Fairbanks and Chaplin, Harold owned his own films, which was highly unusual for the period . . . or for any period, come to think of it.

Harold’s retirement was more or less enforced by a cumulative lack of success in talking pictures, and it must have been difficult for him. He channeled all his energy into hobbies, but the problem with hobbies is that they’re more about filling time than producing something that will stand through time—as Harold’s films have.

But Harold kept busy. He collected old cars. He prided himself on his stereo system—the living room featured thirty-six speakers when he really cranked it up gold leaf would drift down from the ceiling like snow. Harold also became fascinated by the theory of color and started painting, and he even took up 3D photography. He ended up with more than six thousand 3D photographs. He was, in short, very interested in life. He was loyal to his staff; there were a few people he kept on salary that had been with him since the 1920s.

But in some respects, Greenacres was a strange house. Harold was consumed by his hobbies . . . and by young women. Everybody else was left to more or less fend for themselves. Mildred Davis, his wife, quietly drank. His son Harold Jr. was gay, and had a strained relationship with his father. It was a huge place for only five people, and it would have been possible to go for days without seeing anybody.

Harold died in 1971, but I retain a soft spot for both him and his unparalleled home; I shot episodes of Switch and Hart to Hart there—my way of staying in touch with my old friend. Harold’s granddaughter Suzanne has shepherded Harold’s movies—the most valuable part of her inheritance—with great diligence and care, so that future generations will always be able to appreciate what a great comedian and producer Harold was.

Harold, his family, and Greenacres will always be in my heart.

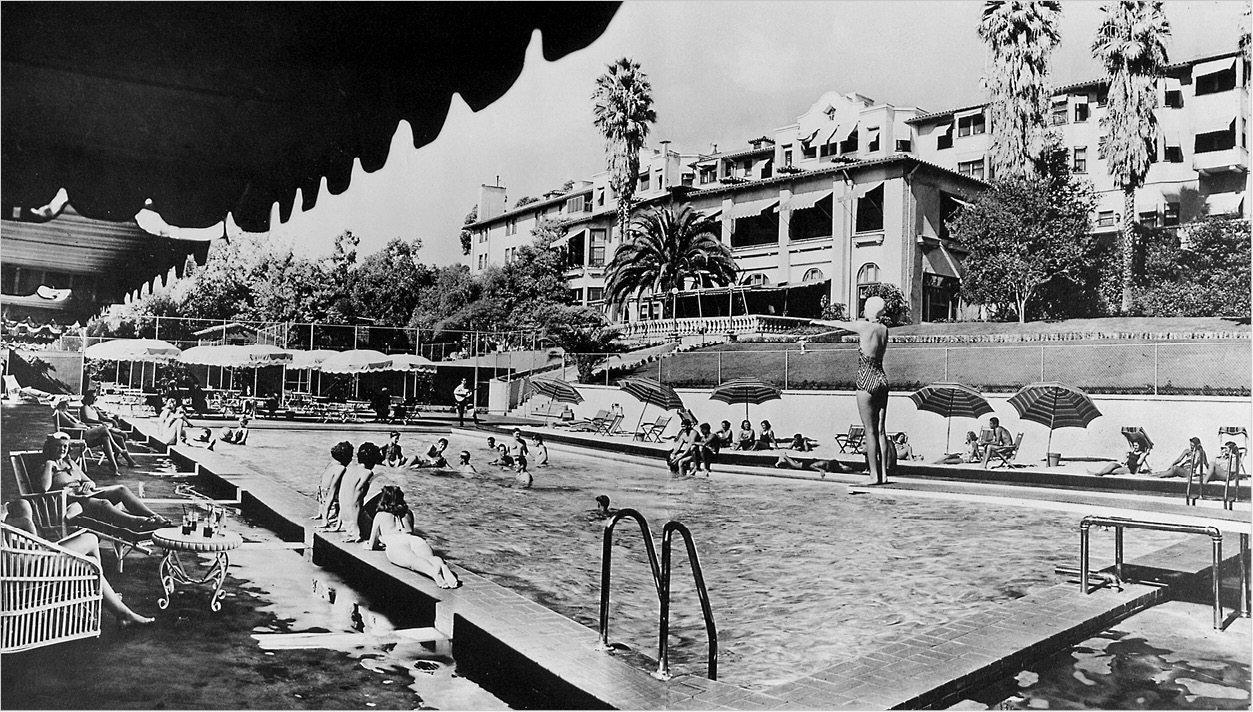

By the time I started going to the Beverly Hills Hotel in the late 1940s, there were already legends about the place, and there would be more in the future. Here are some that I know to be true:

Will Rogers and Spencer Tracy did play polo in what used to be a bean field behind the Polo Lounge. Clark Gable and Carole Lombard did have trysts there while waiting for his divorce to become final. “We used to go through the God-damnedest routine you ever heard of,” Lombard recalled. “He’d get somebody to go hire a room or a bungalow somewhere. . . . A couple of times the Beverly Hills Hotel. . . . Then somebody would give him a key. Then he’d have another key made, and give it to me. . . . Then all the shades down and all the doors and windows locked and the phones shut off. . . . But would you believe it? After we were married, we couldn’t ever make it unless we went somewhere and locked all the doors and put down all the window shades and shut off all the phones.”

That was Garson Kanin reporting what Lombard had told him, and I think it’s accurate until the end, when she claims that Gable had performance anxiety unless the place was locked down tight. I knew Clark, and I can assure you that, while he would have made sure the door was locked, that would have been the extent of his paranoia.

The pool at the Beverly Hills Hotel.

Photofest

Guests playing mini-golf on the grounds of the Beverly Hills Hotel.

Photofest

In other romances, Marilyn Monroe and Yves Montand did carry on their affair in bungalows 20 and 21 while making Let’s Make Love, and Elizabeth Taylor did spend several of her honeymoons in the bungalows.

Howard Hughes kept three bungalows rented at a time. For around thirty years beginning in 1942, Bungalow 4, which had four rooms, was for Hughes’s personal residence. Bungalow 19, which he kept for Jean Peters, his wife, had three rooms. (It should be mentioned that Bungalows 4 and 19 were far apart.) Bungalow 1C was for his bodyguards.

There were times when Hughes would have as many as nine of the bungalows rented, a couple of which would be occupied by girls he had signed for RKO. The rest would be empty.

He also would occasionally book the Crystal Room on thirty minutes’ notice. The Crystal Room held a thousand people, but Hughes’s meetings usually involved only four. Once, Hughes’s Cadillac was parked at the hotel for two years without ever being moved. The tires all gradually flattened, but nobody inflated them and nobody moved the car.

Were any average hotel guest to leave his Cadillac on the grounds to deteriorate, the car would be towed and the owner would be presented with the bill. But Hughes was too good a customer for the hotel to take any such drastic measures.

By 1948, Hughes’s injuries from his Beverly Hills plane crash were beginning to overwhelm him. He would stay inside Bungalow 4 for months at a time. I remember the staff at the hotel mulling over Hughes’s eccentricities—the way he would order roast beef sandwiches (the hotel went so far as to designate a “roast beef man,” who was the only one who had been able to master Hughes’s careful instructions about how to prepare them) accompanied by pineapple upside-down cake. He would tell the staff to stick the sandwiches in a tree, then retrieve them when nobody was around, so no one would know in which bungalow he was staying. He also liked Hershey chocolate bars and Poland Spring water.

In 1949 John Steinbeck met his last wife at the Beverly Hills Hotel. He was in town working on Viva Zapata! and a friend offered to fix him up with Ava Gardner. Gardner wasn’t interested, so the friend fixed him up with Ann Sothern instead. They hit it off, and he invited her to visit him in Monterey. She brought along a friend named Elaine Scott, who was married to Zachary Scott. But not for long—Steinbeck and Elaine hit it off to such an extent that both Ann Sothern and Zachary Scott faded into the distance. Supposedly Sothern never forgave Steinbeck . . . and quite probably never forgave Elaine Steinbeck, either.

Other bungalows had other famous guests. Bungalow 5 was the favorite of Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, and Paul and Linda McCartney liked it as well. Bungalow 9 was the home of Jennifer Jones and Norton Simon for five years. Bungalow 11 sheltered Marlene Dietrich for three years, including her custom-made seven-by-eight-foot bed. Bungalows 14 to 21 were known as “Bachelors Row,” and were the favorites of Warren Beatty and Orson Welles among many others.

By the 1950s, the Beverly Hills Hotel was synonymous with Beverly Hills itself. But in fact, in 1933 the hotel had closed because of the Depression and stood vacant for two years, until the Bank of America reopened it a year later.

In 1942 the hotel was purchased by Hernando Courtright, who was a vice president at the Bank of America. He had no experience in the hotel business, but he knew a good opportunity when he saw one, so he raised one hundred thousand dollars from Harry Warner, Irene Dunne, and Loretta Young*—notice the pedigrees. Then he borrowed another seventy-five thousand dollars to remodel the place.

Rita Hayworth posing poolside at the Beverly Hills Hotel.

Getty Images

That same year Courtright rechristened the El Jardin Restaurant the Polo Lounge to pay tribute to demon polo enthusiasts Will Rogers, Tommy Hitchcock, and Darryl Zanuck—and as such it’s been more or less constantly successful ever since. Toward the end of the decade, Hernando gave the place its first major redecoration. In 1947 he opened the Crystal Room and the Lanai Restaurant, which later became the Coterie.

Courtright’s wife, Firenza, described what he accomplished: “He had a business side and a social side and his business was hospitality. He was a showman, setting the stage for each visitor. He had a great sense of style and, as well, an extra effort to push himself harder than anybody else. In many ways, running [the] hotel was like running a small country.”

Hernando also broadened the number of amenities available at the hotel. Francis Taylor, the father of Elizabeth, opened an art gallery in the downstairs shopping area in 1939, and through the war years the Francis Taylor Gallery became an increasingly important venue for art. Francis sold a lot of California Impressionists, such as Granville Redmond (a deaf artist who had a studio at the Chaplin lot on La Brea for a number of years and who also appeared in some of Chaplin’s films). Francis also sold work by Augustus John. His prices were reasonable, so actors who were also discerning collectors, such as Vincent Price, James Mason, and Greta Garbo, purchased a lot of art from him.

Interestingly, although its “Pink Palace” moniker may seem as old as the hotel itself, the hotel wasn’t actually painted that color until 1948 under the direction of Paul Revere Williams, who also designed the customized cursive script for its logo. Williams was a very dignified, classy man who was born in 1894 and who encountered all the discrimination you might expect would face a young black man in that era. “I determined, when I was still in high school, to become an architect,” said Williams. “When I announced my intention to my instructor, he stared at me with as much astonishment as he would have displayed had I proposed a rocket flight to Mars. ‘Who ever heard of a Negro being an architect?’ he demanded.”

Williams knew that he was going to have to depend almost entirely on white clients, so his first impression had to be faultless. Paul was light skinned, always impeccably dressed, and had taught himself to draw upside down. As soon as a client sat down with him, Paul would start sketching out the plans upside down, which would quickly disarm anyone who was taken aback by the fact that his architect was black. And then Paul would ask for suggestions, and the customer would become a full partner in the project. Brilliant psychology.

In 1949 Williams created the new Crescent Wing, which added 109 rooms to the hotel, and turned it from a T plan to an H plan. Also overhauled were the Polo Lounge and the Fountain Coffee Shop, and the lobby took on its timeless pink and green color scheme that’s been maintained ever since.

The pink and green banana leaf wallpaper, however, was actually the work of Don Loper, who made his name as a dress designer for, among many others, Marilyn Monroe.

It’s a mark of how brilliant Paul’s design for the Polo Lounge was that his is the only hot spot I can think of that has survived unchanged from 1949 to the present day.

Paul is an example of the remarkable openness of Los Angeles to the new, the untried in architecture and style. I think this was possible because you had a set of circumstances that weren’t replicated anyplace else in the country: a basically thriving local economy, a large group of talented architects, and—most important—clients who were interested in anything theatrical or new.

When I started going to the Polo Lounge in the late forties, it wasn’t terribly expensive by Hollywood standards—a daiquiri might cost you seventy-five cents, but a Pimm’s would run more than a dollar and a bottle of Mumm’s Cordon Rouge champagne from 1929 would set you back more than twenty dollars. So the tourists stayed away simply by dint of the tabs.

Paul Williams had completed all his additions to the hotel by the time Stanley Anderson died in 1951. Stanley was one of the pioneers of Southern California, but outside of his participation in the birth of Beverly Hills and the hotel that bears the town’s name, he’s not remembered by many people. But he’s very much remembered by me.

Hernando Courtright sold the place in 1953 for $5.5 million, and by that time the Beverly Hills Hotel was the premier hotel in the area. He continued managing the place for a couple of years, but he didn’t like the new owner, a man from Detroit named Ben Silberstein. And then things got really interesting: Hernando’s wife left him for Silberstein. Courtright then took over the Beverly Wilshire, which he ran very successfully until he sold it a year before his death in 1986.

Hernando Courtright was a good man and a wonderful hotelier. He really knew how to run a place, and he ran it beautifully. Scandals, whether on the part of the guests or the staff, happened mostly out of range of the newspapers, and completely out of range of the guests. The atmosphere was smooth and utterly unruffled. As far as the public was concerned, the Beverly Hills Hotel was the chicest place in town. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor would stay there when they were in town, as would Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon. When Charlie Chaplin came back to Hollywood in 1972 to accept an honorary Oscar, he stayed at the Beverly Hills Hotel. A lot of the people went there for Hernando as much as they did anything else. When you drove down to the hotel and went into the Polo Lounge to have a drink, it was different than going to any other place in town.

Hernando’s great innovation was psychological. In his view, Beverly Hills was not a resort area, nor even a suburb: it was uptown Los Angeles. Hernando wanted to make the town the equivalent of Fifth Avenue in New York or Worth Avenue in Palm Beach, and the Beverly Hills Hotel was, you might say, the anchor store—the prestige destination in a town full of them.

Today, the twenty-two bungalows are set amid lush tropical gardens, with private walkways that snake through groves of coconut palms, oleanders, and bougainvillea. The landscaping is dense in order to give the bungalow inhabitants the privacy they desire, and often need.

The bungalows, which are basically tile-roofed mini-haciendas, have “privacy lights” instead of “Do Not Disturb” signs. They all have fireplaces, full kitchens, and fresh orchids in the bathrooms. Some bungalows have two or three bedrooms, others four.

Since 1987, the Sultan of Brunei has owned both the Beverly Hills Hotel and the Hotel Bel Air, and you may make of that what you will. The sultan is an oilman, but he also loves to play polo, so in that respect the ghost of Hernando Courtright should be pleased, although as far as I’m concerned it’s outsourcing gone berserk.

The Beverly Hills Hotel is emblematic of the best aspects of the town it anchors. People who don’t know any better think the movie business and, by extension, America, has always been just one thing, permanent and unalterable, but the closer you look at history, the more you realize that everything that lasts—like, for instance, the Beverly Hills Hotel—has been reinvented numerous times and by numerous people.

When men like Hernando die, there’s a loss of great personalities, not to mention a loss of history. No matter how well a corporation runs a hotel or a restaurant, the personal touch is gone.

Just one example: They took out the tennis courts at the Beverly Hills Hotel, so the two men who ran them for years, Alex Olmedo and his brother, David, also disappeared. Alex was a joy, a Peruvian who won four NCAA titles and played on the Davis Cup team for America. Kate Hepburn took lessons from Alex, as did Robert Duvall and Chevy Chase.

Bill Tilden taught there. Many wonderful people went to those courts. It was a little piece of Hollywood history, but, like so much of Hollywood history, it’s gone.

Just about the time I arrived in Hollywood, if you rode down the ramp from Ocean Avenue to Santa Monica, Marion Davies’s palace—I don’t use the word lightly—was just off to the right, and the beach houses of Harold Lloyd, Norma Shearer, Louis B. Mayer, and Jesse Lasky were farther on in that direction. To the left off the ramp were Leo McCarey, George Bancroft, and Norma Talmadge, and a couple of places owned by Ben Lyon and Bebe Daniels.

Norma Talmadge’s place at 1038 Ocean Front had a particularly distinguished list of inhabitants. Randolph Scott and Cary Grant had lived there in the mid-thirties, and Cary had kept the place when he married Barbara Hutton. After that, Brian Aherne lived there; Howard Hughes rented the place for a time, as did Grace Kelly. Roman Polanski and Sharon Tate lived there as well. Douglas Fairbanks was a couple of doors down in a house he had initially bought as a weekend getaway, but converted to his full-time residence after his divorce from Mary Pickford.

Norma Talmadge is forgotten today, which is sad, because she was a fine emotional actress, and one of the three or four biggest female stars of the silent era. (The reason nobody remembers her is that very few of her films survive.)

When she built the place in the late 1920s, she was married to Joe Schenck. I’ve always wondered whether the Norman design of the house was an elaborate pun on her name. The interior was decorated mostly in a Spanish motif, although Norma’s bathroom was done with tiles from Malibu Pottery, which was among the most beautiful work ever done in that medium. Interestingly, Norma had almost nothing in her house that indicated she was a movie star, other than a portrait of her over the fireplace in the living room.

Norma lived there for about five years, after which she divorced Schenck and took up with Gilbert Roland, a good friend of mine in later years. Gil always regarded Norma as the great love of his life, which, for a compulsive ladies’ man, is really saying something.

Although Norma’s career ended after only two sound pictures, she had held on to her money—something that couldn’t be said of a lot of silent film stars. She had two other beachfront properties in Santa Monica, as well as other real estate investments around Los Angeles.

These Santa Monica and Malibu houses—always excluding Marion Davies’s place, which could have sheltered an army—looked quite modest. They still do—most of them are still there, although they’ve been heavily altered over the years. Most of them were a complete change of pace from the Spanish influence that was predominant in Hollywood. Some derived from Cape Cod style; others reflected a Newport or Monterey influence.

If Hollywood was prone to strange fads—the famously arrogant director Josef von Sternberg had a house designed by Richard Neutra in Chatsworth that looked like an aluminum pillbox that just happened to have a moat around it—it had an even stranger love of huge parties, as if in defiance of the Depression. Hearst loved to throw dos at San Simeon, but also at Marion Davies’s huge house in Santa Monica, which the naive often assumed was a resort hotel. Actually, it was the only competition Harold Lloyd had for the most lavish movie star estate.

The Santa Monica beach house was by no means Marion’s primary residence. That was actually a Spanish-style mansion at 1700 Lexington Road in Beverly Hills. The Beverly Hills house was Marion’s preferred venue for parties, simply because the Santa Monica house was too damn big—it could supposedly hold two thousand guests, which sounds more like Buckingham Palace than Santa Monica, but then Marion’s place wasn’t much smaller than Buckingham Palace.

There was a small-town atmosphere in Hollywood then. One or two nights a week, Davies would invite a few close friends to her place. Since her close friends were named Chaplin and Fairbanks, it may sound like an intimidating evening, but the evenings mostly consisted of dinner and charades. A few weeks later, Chaplin or Fairbanks would return the favor. Sometimes Marion would hire a bus, fill it with ten or twenty friends, plenty of food, maybe a musician or two, and take off for Santa Monica beach, where they would have a late picnic and a bonfire.

William Randolph Hearst built the Santa Monica palace for Davies in 1928, the last, flamboyant year of the silent era. Money was clearly no object. The house held down 750 feet of oceanfront real estate—and this at a time when anything more than fifty feet was regarded as a luxury. Hearst assembled the land piecemeal, using various pseudonyms in order to keep the prices down.

The story goes that the last parcel of the property belonged to Will Rogers, which Hearst wanted for the tennis court. The land was worth about five thousand dollars, but Rogers found out who the buyer really was. By the time they were through negotiating, Rogers got a hundred thousand dollars for his parcel.

To give you some idea of the scale of Davies’s place, it had five buildings, a hundred ten rooms, fifty-five bathrooms, and thirty-seven antique fireplaces. For one party in 1937, to which I was unaccountably not invited, they installed a merry-go-round on the grounds.

The Beach House was small only in comparison to Hearst’s San Simeon, which was situated on 240,000 acres. But you couldn’t make movies and commute from San Simeon, so Hearst simply built his mistress an equivalent in Santa Monica. While the exterior was Neocolonial in design, inside it was eclectic. There were vast rooms on the first floor, a ballroom, a theater, dozens of bedrooms on the second floor—a random succession of grand rooms that had no connection to one another.

As with San Simeon, Hearst’s decorating principle was simple: he bought entire rooms out of various European castles and installed them in Davies’s new house. The dining room, drawing room, and reception hall came from Burton Hall in Ireland. Then there was a ballroom from an eighteenth-century Venetian palazzo. A tavern in the basement had been a pub in the Elizabethan era, and sat fifty. Davies herself lived on the top floor of the main building, with a spectacular view that looked out to sea and up the coast.

There’s a story that gives you some idea of the scale on which Hearst and Davies lived. It seems that Davies had ordered a twenty-four-by-one-hundred-foot custom rug for the movie theater on the second floor. After misadventures with the shipping, the rug finally arrived, and it was found that there was no possible way it could be brought inside the house.

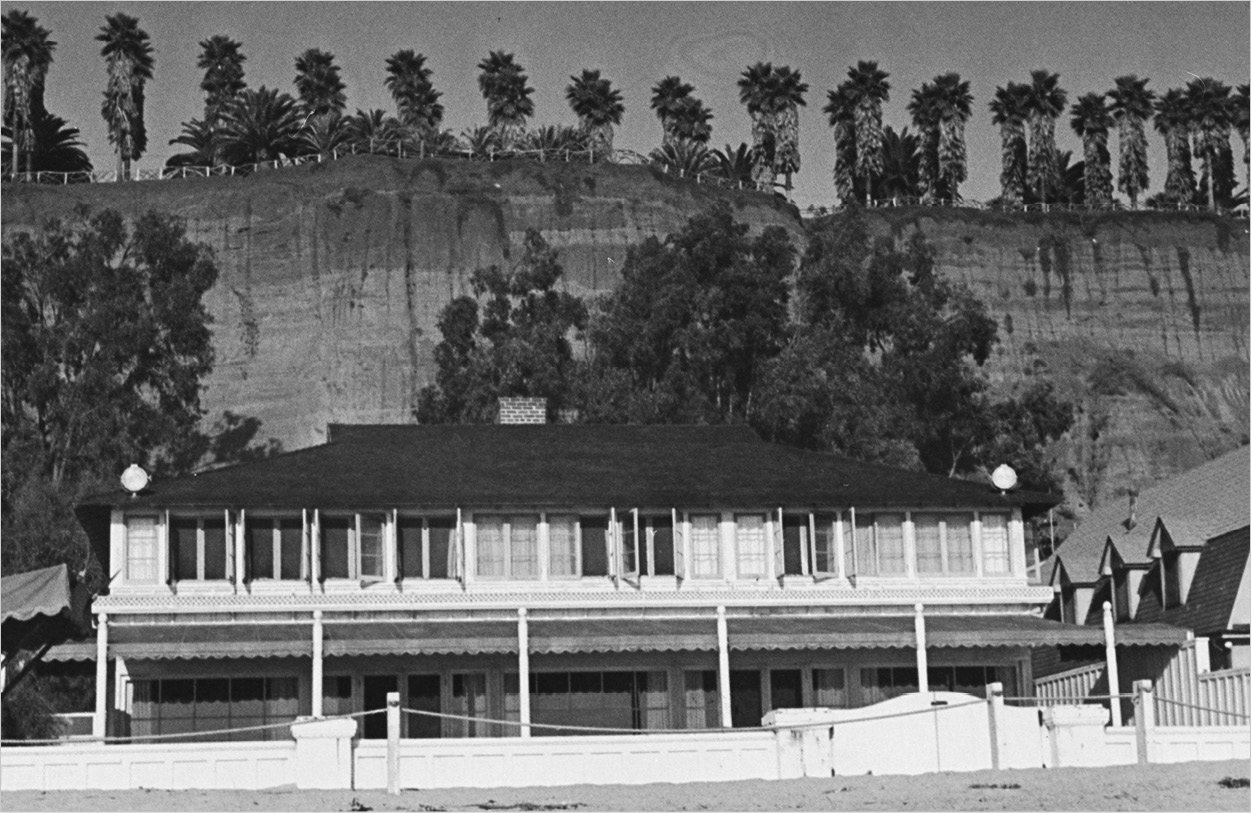

The beach-side facade of Marion Davies’s Santa Monica home, known as Oceanhouse.

Everett Collection

No problem. Davies simply ordered part of the wall to be removed; then the rug was lifted into the house by crane, and the wall was rebuilt. It sounds like the type of, well, off-the-wall thing that today would be done only by Arab sheikhs residing in Dubai. In that era, Hollywood was Dubai.

The Beach House was a popular site for theme parties—Pioneer Days, or Tyrolean, or whatever incongruous thing they could dream up. One time Davies threw what she called a “Baby Party,” for which all the guests had to dress up as children. Joan Crawford came as Shirley Temple, while Clark Gable made an appearance as a Boy Scout. (It was an echo of a similar party in the 1920s, when Alla Nazimova appeared in diapers and Wallace Reid came as Buster Brown.) Perhaps the most creative party involved an invitation demanding that couples arrive wearing exactly what they had on when their romance began. Lee Tracy and his wife came in a shower curtain.

Once, Norma Shearer showed up as Marie Antoinette for a party billed as all-American. Norma’s hoop skirt was so huge that seats had to be removed from her car before she could get in.

Davies was a good-natured woman, greatly loved by everybody who knew her, but Shearer was a thorn in her side. Like Joan Crawford and most of the other actresses on the MGM lot, she was jealous of Shearer’s ability to land film roles simply because she was married to Irving Thalberg. And now this.

Davies told Shearer she’d have to take off the dress if she wanted to enter the party. The two women got into it, but Shearer got her way. Hearst may have been running a publishing empire, but Irving Thalberg ran production at MGM, where Marion was making her movies.

And that wasn’t even Shearer’s most aggressive look-at-me display. Hedda Hopper once told me about a party that Carole Lombard threw. It was supposed to be a white ball—nothing but white gowns on the women. The event was to be held at the restaurant Victor Hugo—the perfect setting for such a lavish display. Norma came late, as was her wont, but that wasn’t what proved so devastating: she was wearing a bright red gown.

It was all a reenactment of the climactic scene in Bette Davis’s Jezebel, but the people at the party weren’t amused. Shearer had gone far out of her way to show up the hostess, and that was simply bad form. Like Marion Davies, Carole Lombard had a widespread reputation for being a salt of the earth dame, but she was livid and stormed out, followed closely by Clark Gable.

I went to school with Norma’s son, Irving Thalberg Jr., who brought me over to the house one day to meet her. She was in bed, where Irving had led me to believe she spent a great deal of her time, resting up so she could look radiant at parties. She was sweet, and signed a still for me, which I still have. But stories like the one Hedda Hopper told me indicate that to get between Norma Shearer and something she wanted would have been a very bad idea.

Marion Davies lived at Beach House until World War II. At that point Hearst became worried about a Japanese invasion. Don’t laugh—there was a great deal of fear in California about just such a possibility. Spielberg’s 1941 wasn’t much of a movie, but it was based on fact. Davies moved back to San Simeon and her house in Beverly Hills. But because she disliked San Simeon—she thought it was gloomy—she spent most of her time in Beverly Hills. Years later, long after Davies had died, that house became famous when it was used as the location for the home of the movie producer played by John Marley in The Godfather. A horse’s head in Marion Davies’s old bedroom!

Hearst’s empire contracted radically during the Depression and afterward. Part of it was the economy, and part of it was that he was extremely conservative at a time when the dominant philosophy was the New Deal. He couldn’t afford both places, so the Beach House was sold for six hundred thousand dollars—which might have paid for one of the ballrooms—and he held on to San Simeon.

In 1947 Beach House became a hotel, called Oceanhouse, but the venture failed and the main house was demolished in 1956; three years later the property was sold to the state of California. All that’s left of one of the great mansions of California’s past is one guesthouse, which had been used by Davies’s family. Still later the property was taken over by Wallis Annenberg, who turned it into a public community center. I’ve gone there with my grandson Riley, holding his hand and reflecting on the vast palace that once stood on the spot. Someday, when he’s old enough, I’ll tell him all about it.

Small beach cottages helped launch the decorating career of Billy Haines. Haines had opened an antiques shop in 1930 while he was still under contract with MGM. He had an innate understanding of his potential market; Hollywood had attracted thousands of people from all over the world, most with very limited educations but with boundless ambitions. They needed to be led, but gently. The antiques shop displayed Haines’s antiques in complete room settings, so that people without the gift of visualization could see what the chairs or couches or vases would look like in context. And of course it also allowed Haines to sell extra pieces, and sometimes entire room ensembles.

After his acting career ended, Ben Lyon became the head of talent at 20th Century Fox. Ben told me that it was he and his wife Bebe Daniels—not Joan Crawford—who had given Haines his first commission as a decorator.

Lyon had a cottage with about thirty feet of beach frontage, and he told Haines to make it sufficiently attractive so they could rent it for extra income. Haines enclosed the porch, making it part of the living room, and decorated everything in red, white, and blue. His bill for everything, including the furniture, was twenty-five hundred dollars.

Because Haines had been a star himself, he had an intimate understanding of a star’s mentality and a star’s needs. Basically, he made them feel special. Plus he knew how to gain a star’s trust—perhaps the most valuable quality a designer (or, for that matter, a director) can have.

Once Haines was done redecorating Carole Lombard’s house, the drawing room featured six shades of blue velvet and Empire furniture. Her bedroom had an oversize bed in plum-covered satin, with mirrored screens at either side. The dining room had satin curtains that trailed on the floor. The result was every bit as sleek as Lombard herself, and totally feminine. That was the way Carole lived until she married Clark Gable, who would have felt out of place in such surroundings.

Haines did Lombard’s and Joan Crawford’s houses for free, as a favor to friends, figuring that the Hollywood scuttlebutt would bring customers to his door.

In 1935, he moved his shop to Sunset Boulevard, quite close to all his prospective clients in Beverly Hills. I remember driving by Haines’s imposing double-doored entrance hundreds of times over the years. On either side of the doors were large glass niches with oversize glass vitrines.

Very posh.

Haines’s next big commission was George Cukor’s house. “It looks just like a Hollywood director’s home ought to look,” said Cukor when he beheld the results.

In 1934 Frank Lloyd Wright declared that California’s “eclectic procession to and fro in the rag-tag and cast-off of the ages was never going to stop.” This was his way of declaring defeat; he had been trying to class up the joint by designing several homes in the area: the Hollyhock House and three other concrete-block Mayan-style houses, designed and built between 1919 and 1924. They’re splendid examples of Wright’s midcareer style—and they’re all still standing—but they only added to the stylistic confusion of LA.

Hollyhock House is located at the corner of Sunset and Vermont—not known as a particularly great neighborhood now, but in 1919, when ground was broken, it was virgin territory. It was commissioned by Aline Barnsdall as a home that would overlook an artist’s colony and theater complex. Wright was always juggling multiple projects, so when construction began he was spending a great deal of time in Tokyo, where he was designing the Imperial Hotel. While Wright was traveling, so was Barnsdall, and the distance bred a lot of disagreements, which only increased when they met face-to-face.

“How can you put a door there?” she’d yell. “I don’t like it and I won’t have it. Change it!”

“No!” Wright would yell right back. “That’s the way it’s going to be! I won’t change it.”

She’d insist, and he would go ahead and do what he wanted to do. It was like a bad marriage. The upshot was that Barnsdall lived in the house only for a year, after which she offered it to the city as a public park and art center.

While all this was going on, Los Angeles was exploding in all directions. The population had grown from 576,673 in 1920 to 1.2 million in 1930. Four hundred thousand of those people had arrived in the space of just five years. All those newcomers had to live somewhere, and the Southern California real estate boom was quite probably the largest and most loosely managed in history.

Meanwhile, areas farther west, such as Brentwood and Pacific Palisades, had begun to attract some movie people as Beverly Hills began to be afflicted with tour buses and gawkers. Will Rogers had come to dislike the town because it was getting too congested for him—the population that had been all of 634 in 1920 was 17,428 in 1930. A one-room schoolhouse at Sunset and Alpine had been torn down, and a one-car trolley on Rodeo Drive had also vanished. A great debate raged for a time about whether or not a dime store should be allowed to open on a street south of Santa Monica Boulevard; ultimately the issue was decided in favor of the dime store.

All this was too much for Rogers. He sold his house on North Beverly Drive and bought a ranch that encompassed several hundred acres at the far reaches of Sunset Boulevard in Pacific Palisades, where he lived for the rest of his life, and where he built one of the finest polo fields in the West.

Years later, I would buy a place of my own just around the corner from Rogers’s ranch, which by then was the Will Rogers State Park. I lived there with my daughters and Jill for more than twenty years, and that land was a great healing force for me, just as it had been for Will Rogers.

When Rogers bought his property, he was pretty much alone out in Pacific Palisades, which was just the way he liked it, if only because it was a long drive to the studios, which were in Hollywood (Paramount, RKO, Columbia) or the San Fernando Valley (Warner Bros.).

Because of proximity to their workplace, a lot of the people at Warner bought places near Burbank and North Hollywood. Bette Davis bought a two-story redbrick Tudor house behind a wall in Glendale, which was only about ten minutes from the studio. This meant she could sleep for an extra hour in the morning—no small thing when you have to be on the set, in wardrobe and makeup, by eight a.m.

Relatively rural places like Sherman Oaks, Encino, and Tarzana were mostly barley fields and orange groves, with a smattering of chicken ranches, until the 1950s. For those who liked country living, these were choice locations. Clark Gable and Carole Lombard had a thirty-two-acre ranch in Encino, fronted by a white brick and frame colonial. It was all very homey, with early American furniture and a room set aside for Clark’s collection of rifles—he was an excellent skeet and bird shooter.

By the late 1930s and 1940s, a lot of incredibly opulent houses had begun to be built in Bel Air and, just outside its limits, in Holmby Hills. One of the first stars to move to Holmby Hills was Jean Harlow. Her Georgian mansion was all crème and gilt, and it was also huge—but then, her mother and her mother’s husband also lived with her. William Powell, with whom Harlow had the last serious relationship of her life, thought the house was ridiculous and her relationship with her mother destructive; he urged her to get rid of the place and save some money before her mother drove her into bankruptcy. She followed his advice and rented a much cheaper house, but she died before she was able to put down any roots.

Without question the most opulent house I have ever been in was Jack Warner’s.

It was an immense Georgian mansion, more than thirteen thousand square feet, sitting on nine acres of property. It had two guesthouses, terraces and gardens, three—count ’em, three—hothouses, a nursery, and a nine-hole golf course. Harold Lloyd, Jack’s next-door neighbor, also had a short nine-hole golf course on his property, and Jack built a bridge between the two properties so guests could play eighteen if they so desired.

The interesting thing about Jack’s estate—“house” doesn’t begin to cover it—was that Jack put it together piece by piece over a ten-year period. He originally bought three acres in 1926 and built a fifteen-room Spanish mansion. But three acres felt insufficient, so Jack added another parcel of land, and then another.

The grounds were completed in 1937, at which point Jack turned his attention to his house. He hired Roland Coate to enlarge and completely redesign the old Spanish mansion into a new Georgian mansion, and Coate went to town on the assignment.

When he was done, besides the house itself and the guesthouses, there were gas pumps and a garage where repairs could be done on Jack’s fleet of cars. But everybody agreed that the pièce de résistance was the golf course. The holes were on the short side—pitch and putt, really—but that wasn’t the point. The point was that Jack had enough power and money to customize a golf course on some of the most valuable real estate in the world.

If you didn’t already know that Jack was a rich and powerful man, the entrance to his mansion would have told you. Past the iron gates was a winding driveway lined by sycamores. You ended up at a brick-paved motor court by the portico—all white and classical. Across the way was a fountain, and beyond that were landscaped terraces decorated with statues and urns.

Needless to say, the interior of the mansion maintained the same impression of grandeur. Jack hired William Haines to do the decoration. Haines liked big houses.

Billy filled the house with antiques befitting the setting—authentic George III mahogany armchairs, writing desks, eighteenth-century Chinese wallpaper panels. (At this stage of his career, Haines liked French and English antiques with chinoiserie accents—a weird kind of Regency effect. In later years, he modernized his style to something more aerodynamic and Scandinavian looking.)

The front door opened into a two-story hall with a parquet floor. Sweeping up the side was a curving cantilevered staircase. On the wall as you ascended the staircase were paintings by Arcimboldo, the eccentric artist—well, I’ve always thought he was eccentric—who made portraits out of fruit and vegetables.

The library was where Jack spent the most time, because it had been converted into a screening room where he watched movies with his executives. When you twisted the head of a Buddha, paintings would rise and a screen would emerge.

The library, which also held a collection of scripts from Warner Bros. films, was largely decorated in orange, from the couches to the curtains. Because of the color scheme and the low furniture—so heads wouldn’t get in the way of the projector’s beam—it had a more modern feel than the rest of the house, except for some Louis XV–style panels that broke up the walls and drapes.

Somewhere in the house over a mantel, I recall a portrait of Ann Warner painted by Salvador Dalí. The bar had a large wooden floor and more orange accents, with Tang dynasty pottery and a couple of huge candlesticks that I seem to recall came from a Mexican cathedral. Behind the bar were statues of the Buddhist deity Guanyin, which Ann had insisted reappear in various places throughout the house.

I always wanted to ask Jack what he thought about Buddhism. Maybe he figured a little Buddhism on the side amounted to hedging his bets, but the truth is I don’t think Jack Warner ever believed in anything except Jack Warner.

Overall, the house was more like an architectural museum than a place you’d actually want to live. When you had the privilege of dining at Jack’s house, the silverware wasn’t silver but gold, and a footman stood behind every diner at the table.

Ann Warner was a very upbeat lady, vivacious and full of life, even though theirs was a difficult marriage. In the silent days, she and Jack had had an affair, which eventually resulted in his divorcing his first wife and her divorcing her husband Don Alvarado, one of the many actors who vied for Rudolph Valentino’s public after Valentino died. (To give you some idea of the incestuous nature of Hollywood, Don Alvarado later went to work for Jack at Warner Bros., using the name Don Page.)