CHAPTER 7

A Tale of Two Cities:

On the Capital of Ghâna

The Aoukar, Present-Day Mauritania, around 1068

We must begin by stating, in order to remove any ambiguity, that the Ghâna of the Middle Ages is not the country of the same name, the Republic of Ghana, a coastal nation on the Gulf of Guinea between the Ivory Coast and Togo, which took its name from its ancient predecessor only at independence. Moreover, it is even possible that the whole history of Ghâna and its avatars is only that of a name, a ray of light that from its first appearance on the scene designated and overexposed a Sahelian political formation that we know very little about. Except that, according to al-Bakrî, before becoming the name of the capital city, then of the kingdom, Ghâna was the title borne by the country’s sovereign—whose kingdom would have been called Awkâr.

Abû Ubayd al-Bakrî could have succeeded his father, the sole ruler of the modest Islamic principality of Huelva and Saltés, on the Iberian Peninsula’s Atlantic coast. Given the uncertainties of political careers in the eleventh century, however, he had the good sense to make a name for himself, beginning with his exile in Cordoba, as the preeminent geographer of his day, while simultaneously acquiring a reputation as a philologist, drinker, and book collector. This erudite pleasure seeker probably never traveled outside of his native al-Andalus, but he did have access to official archives and earlier written materials since lost. It is to him, then, that we owe the magnificent, singular description—tucked away in the pages devoted to the trade routes of the Sahel in his Book of the Itineraries and Kingdoms—of the realm that owing to approximation and metonymy has been called Ghâna ever since; here we see the beginnings of a glorious history of African kingdoms. It was for this very reason that the British colony of the Gold Coast borrowed its name when declaring independence in 1957.

Ghâna was not the first significant African kingdom, nor was it the only one, nor even the most important of its day; but it was described by al-Bakrî. Ever the accurate author, he did not feel the need to convince his readers that Africans were inferior beings. He tells us that the current king (around 1068) was a certain Tankâminîn, who ascended the throne after the death of his maternal uncle in 1062. This custom must have surprised an Arab author: matrilineal succession did not exist in North Africa, except among an atypical Berber group, the Tuaregs, but it was common in sub-Saharan Africa. The king exported gold to Islamic lands and collected taxes on the loads of salt and copper that entered his country. His palace and dwellings were surrounded by a fortified wall. When domed-roofed houses appear in the text, one is tempted to refer to them as “huts,” bringing to mind wattle-and-daub dwellings. But the text speaks explicitly of architecture made from stone and wood. We find similar residences all around the royal enclosure, as well as groves and woods. It was in these spaces forbidden to visitors that the priests saw to the local religion, what al-Bakrî called “the religion of the magi” (madjūsīya), and what colonial science would later disdainfully call “animism.” Here were found the tombs of the kings as well as “idols,” a somewhat loaded translation of a term (dakākīr) that certainly referred to wooden or terra-cotta statues of former sovereigns, to whom were offered sacrifices and libations of fermented drinks. Al-Bakrî’s informant was a considerably talented “ethnologist,” who, moreover, left his observations in the best possible hands. We recognize a familiar world in his description: an ancestor cult centered on approving or angry deities, protectors of families and lineages, whom it was necessary to appease with regular offerings made under the sheltering canopy of their sacred groves. Near the royal enclosure lay a domed room, around which were positioned ten horses cloaked in fabrics embroidered with gold; dogs, whose collars gleamed with gold and silver, were kept near the entrance. The ceremonial swords and shields held by the pages, arrayed behind the king, were made of gold, while gold was also braided in the hair of the sons of princely families, arrayed to his right. The ministers and the governor of the city sat on the ground. Drums opened the session. Petitioners prostrated themselves and threw soil over their shoulders. The royal audience could begin: its aim was to right the wrongs inflicted on the people by the king’s officers.

It is easy to see that the Aoukar, a natural region of present-day southern Mauritania, derives its name from Awkâr. It is possible that Tankâminîn’s land had had no other name than that. Besides, must a kingdom necessarily have a name when you already have a dynastic title, princely families who accept your legitimacy, and subjects to whom you extend your justice? In these conditions, the name of a region—like the monarch’s title—can very well become, through synecdoche, that of the whole kingdom; all it takes is for a foreign visitor to have felt the need for it. But let’s assume that it was indeed the kingdom’s real name that would be preserved in the local toponymy. Nowadays the Aoukar is the name of a large erg* virtually devoid of human settlement. Still, the region is not entirely sterile: groundwater flows at only a few meters’ depth and fosters the occasional sudden appearance of vast pastures. The sands are “alive” and could have spread to the south over the course of the last millennium.

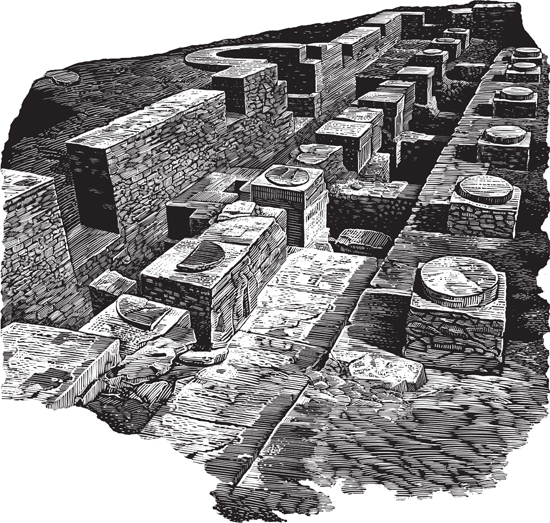

Some scholars have claimed that the site of Kumbi Saleh, on the southern threshold of the Aoukar in the region of Wagadu, in the middle of a basin formed by massifs of fixed dunes, was the capital of the Ghâna of al-Bakrî. We are here on the ecological edge of the sedentary domain: a large pond sometimes appears during the wet season; the first agricultural village is only a few kilometers to the south. Over the past century, several surveying missions and excavation campaigns have been conducted there and have revealed architectural elements and artifacts compatible with the idea of a city in the Sahel at this point in the Middle Ages: the archaeological mound, with a circumference of almost four kilometers and a thickness of seven to eight meters, revealed squares, streets, blocks of buildings made from shale tiles, and a large mosque; as for imported artifacts: small quantities of glazed ceramics, coin weights,* and beads.

This convergence between written and archaeological sources would be sufficient anywhere else to convince us that this archaeological site is indeed that of the capital mentioned in the texts. But even though Kumbi Saleh is without a doubt the most extraordinary of West Africa’s known sites, things are not that simple. Al-Bakrî specifies that the city of Ghâna was made up of two localities separated from each other by six Arabic miles (that is to say, a dozen kilometers); Muslims, by which we understand Arab or Berber merchants, lived in the first, the king in the second. The latter, as we have seen, perhaps had the appearance of a rather loose grouping of stone and wood houses around the royal enclosure where the palace and its outbuildings, dwellings, and courtyards stood. Apart from the audience chamber, a mosque was also located in the vicinity for the liturgical use of Muslims who came as merchants or diplomats. They resided in the other city, which contained twelve mosques. This was not insignificant and probably denotes a compact group of several hundred inhabitants, all surrounded by wells and gardens where they cultivated vegetables, which means that there was irrigation. Between these two poles, there were, from what al-Bakrî says, a number of villages, a sign that if the site is indeed the one we seek, then the desert has overrun it, or, rather, humans have let the desert overrun it. For neither pedestrian surveys nor aerial photography, starting from the earth wall that rings the archaeological zone, have had the slightest luck in locating even an insignificant structure within a radius of several miles.

Two cities in one, according to al-Bakrî. There are thought to be similar examples, from the same epoch, on the Senegal and Niger Rivers: an Islamic city and an African city, distant enough to avoid commingling but close enough to implement an authentic commercial articulation. But isn’t the angle of observation that imposes this duality perhaps a little reductionist in turn? Once settled—or, more likely, kept at a distance—the merchants and clerics of the Muslim city were certainly inclined to approach the royal African city as the unique other pole of a system of trade relations and mutual dependence involving only elites. For in the inevitably dual logic of economic relationships, they were, by the same token, blind to the other facets of the city: the city of Ghâna was perhaps indeed a multipolar space constructed, in reality, from a fabric composed of multiple villages, a royal quarter formed from a variety of domestic, religious, and official spaces, and a residential and commercial center. Plus other spaces: for artisans and soldiers, spots for funerary or devotional practices, and then, as in any agglomeration of neglected neighborhoods, wasteland and sectors in the midst of transformation. Perhaps this was the city: an ensemble divided into “quarters” with distinct functions, containing more empty space than full, more a necessary circulation space than a densely populated area, all of which made the Arab visitor reluctant, and us even more so, to designate what should or should not be considered a “city.” With Kumbi Saleh, exceptionally powerful in terms of its stratigraphy, astonishingly dense in terms of its urban fabric, we are undoubtedly looking at a major site, perhaps not without link to the Ghâna of al-Bakrî—if not with Ghâna, what else? But where were the city gardens, where were the surrounding villages, where was the royal quarter, the sovereigns’ necropolis, the grove where the priests served the ancestors in secret? Only the cartography of a city virtually indistinguishable from its landscape would allow us to grasp the relationships between its sectors. This cartography, if it ever corresponded to a reality other than an idealized or sentimental one—let us admit that the cool shade of a garden contributes more to urbanity than to urbanism—was undoubtedly largely immaterial (urbanity is a quality that leaves few traces) and, in any case, at the margins of the desert, hopeless. If it were necessary to one day relaunch the quest for Ghâna, then we would have to walk first, not dig.

Before the historiographical tradition had its heart set on Kumbi Saleh, Albert Bonnel de Mézières, a French adventurer, explorer, and later colonial administrator, had surveyed the region. He certainly did not go about it in a systematic fashion, nor did he have the support offered by today’s methods of surveying and description. And yet these visits enabled him to discover, within a radius of a few days’ walk around Kumbi Saleh, roughly ten ancient sites where, almost as many times, and always with the same good faith and enthusiasm, he thought he had discovered Ghâna.

Al-Bakrî’s text is available in a critical edition in Arabic and French by Baron MacGuckin de Slane, Description de l’Afrique septentrionale (Algiers, 1913). An excellent translation of the city’s description as given in this chapter can be found in Nehemia Levtzion and J.F.P. Hopkins (eds.), Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History (Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener, 2000), pp. 79–81. For biographical details on al-Bakrî, I used Évariste Lévi-Provençal’s entry “Abū ʿUbayd al-Bakrī,” in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. For a review of the historiographical importance of al-Bakrî, see Emmanuelle Tixier, “Bakrī et le Maghreb,” in Dominique Valérian (ed.), Islamisation et arabisation de l’Occident musulman médiéval (VIIe–XIIe siècle) (Paris: Publication de la Sorbonne, 2011), pp. 369–384. The term dakâkîr (singular dakkûr) is not Arabic and probably comes from a language spoken in the Sahel; in another instance, al-Bakrî employs it with the meaning of “idol” (ṣanam). An attempt at interpreting al-Bakrî’s West African itineraries has been made by John O. Hunwick, Claude Meillassoux, and Jean-Louis Triaud, “La géographie du Soudan d’après al-Bakri. Trois lectures,” in Le Sol, la parole et l’écrit: 2000 ans d’histoire africaine. Mélanges en hommage à Raymond Mauny, 2 vols. (Paris: Société française d’histoire d’outre-mer, 1981), 1:401–428 (despite the French title, Hunwick’s contribution to this chapter is in English); the three authors all accept the identification of al-Bakrî’s Ghâna with Kumbi Saleh, which somewhat restricts the reading of the text. In this regard, a dissident but welcome voice is that of Vincent Monteil, who in his remarkable translation and commentary of the text, “Al-Bakrî (Cordoue 1068). Routier de l’Afrique blanche et noire du Nord-Ouest,” Bulletin de l’Institut fondamental d’Afrique noire, ser. B, 30, no. 1 (1968): 39–116, posed this question (p. 111): “If Kumbi Saleh is indeed this city [the Ghâna described by al-Bakrî], what became of the ruins of the eleven other mosques [that the author mentioned]?” It must be added, however, that only a tiny part of the site has been excavated, and that it remains possible that several mosques have yet to be discovered. On the historiographical construction of the Sudanese kingdoms in the Western imagination, see Pekka Masonen, The Negroland Revisited: Discovery and Invention of the Sudanese Middle Ages (Helsinki: The Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, 2000). J.-L. Triaud has delivered a detailed study of the historiographical construction of Ghâna from the Middle Ages to decolonization: “Le nom de Ghana. Mémoire en exil, mémoire importée, mémoire appropriée,” in J.-P. Chrétien and J.-L. Triaud (eds.), Histoire d’Afrique. Les enjeux de mémoire (Paris: Karthala, 1999), pp. 235–280. The region where Kumbi Saleh is located has been very well described by Jean Devisse and Boubacar Diallo, “Le seuil du Wagadu,” in Vallées du Niger (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1993), pp. 103–115. A short note based on a telegram from Bonnel de Mézières indicated the numerous discoveries he had made in the region in 1914: [Albert Bonnel de Mézières], “Notes sur les récentes découvertes de M. Bonnel de Mézières, d’après un télégramme officiel adressé par lui, le 23 mars 1914, à M. le gouverneur Clozel,” Comptes-Rendus de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 58 (1914): 253–257. The excavations’ results have been only partially published; see most recently Sophie Berthier, Recherches archéologiques sur la capitale de l’empire de Ghana. Étude d’un secteur d’habitat à Koumbi Saleh, Mauritanie. Campagnes II-III-IV-V (1975–1976)–(1980–1981) (Oxford: Archaeopress, 1997). The journal Afrique. Archéologie et Arts has published the hitherto unseen report of D. Robert-Chaleix, S. Robert, and B. Saison. See “Bilan en 1977 des recherches archéologiques à Tegdaoust et Koumbi Saleh (Mauritanie),” Afrique. Archéologie et Arts 3 (2004–2005): 23–48. The same issue contains several other recent articles focusing on structures or artifacts discovered at Kumbi Saleh. Only very brief but useful archaeological syntheses exist in English: see, for instance, Timothy Insoll, The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 228–230, as well as reviews in English of French works, such as Susan Keech McIntosh, “Capital of Ancient Ghana” [a review of Berthier’s book cited above], Journal of African History 41, no. 2 (2000): 296–298.