CHAPTER 21

The Stratigraphy of Kilwa,

or How Cities Are Born

Coast of Present-Day Tanzania,

from the Tenth to the Fifteenth Century

Deep inlets along the coast, marking the mouths of two southern Tanzanian rivers, have formed Kilwa Bay, a basin closed by reefs. Small, meandering rivulets of seawater penetrate the local mangrove cover. An island rises from the middle of the bay, a protected space that also controlled access to the continent. A crop of archaeological sites bear witness to the fact that this bay was a privileged zone of human occupation for a millennium. The current city of Kilwa is on the continent. The most important ruins are on the island: Kilwa Kisiwani, “Kilwa-on-the-island,” in Swahili.

The first thing one sees through the thick curtain of mangrove trees is the massive remains of a vast palace complex. Located atop a cliff in the middle of the open cove that demarcates the northern side of the island, the site is called Husuni Kubwa, or the “large castle” in Swalhili. (We recognize the borrowing of the Arabic word hisn, “fortified enclosure.”) Among the recently restored leveled-off walls, which have not kept their roofs, one first notices doorways to small rooms arranged along the four sides of a vast, closed courtyard; it brings to mind a trading station, both entrepôt and marketplace, framed by shops and storehouses—this was the commercial space. The complex includes several other open-air spaces whose exact functions remain uncertain, but which were undoubtedly suitable for meetings—this was the political space. It is hard to escape the suspicion that this architectural ensemble was intended for the various aspects of the public life of local and foreign elites: receptions, audiences, symbolic exchanges, commerce, taxation, deliberations. Bordering the top of the cliff like a rim; dominating the sea; soberly decorated, although we do note alcoves and moldings; its architecture robust even if the vision of its original elevations is lost to us—this “castle,” whose dedicatory inscription names Sultan Hasan ibn Sulaymân as its builder, was considered the gateway to the Zanj coast. Perhaps it replaced an earlier complex whose ruins are visible immediately to the east of Husuni Kubwa.

The grand mosque was some fifteen hundred meters from the palace, in the extreme northwest corner of the island. With the exception of that of Timbuktu ( 28), it is certainly the largest ancient mosque in sub-Saharan Africa, in any case of those that have come down to us in a recognizable state. It is a vast ensemble whose stone walls retain their original height, and whose roof is made up of alternating rows of cupolas and barrel vaults. Doorways and windows are molded. The interior is a forest of pillars linked by gently pointed arches that give this architecture its fine appearance. Although the building went through multiple transformations up to the eighteenth century, the mosque is contemporary with the palace of Husuni Kubwa; its floorplan has not been altered since the fourteenth century. At the end of the prayer room, behind the mihrâb* oriented to the north in the direction of Mecca, we discover another room that also has a mihrâb.* This is the former mosque, which undoubtedly became too small and was integrated into the walls of its successor.

28), it is certainly the largest ancient mosque in sub-Saharan Africa, in any case of those that have come down to us in a recognizable state. It is a vast ensemble whose stone walls retain their original height, and whose roof is made up of alternating rows of cupolas and barrel vaults. Doorways and windows are molded. The interior is a forest of pillars linked by gently pointed arches that give this architecture its fine appearance. Although the building went through multiple transformations up to the eighteenth century, the mosque is contemporary with the palace of Husuni Kubwa; its floorplan has not been altered since the fourteenth century. At the end of the prayer room, behind the mihrâb* oriented to the north in the direction of Mecca, we discover another room that also has a mihrâb.* This is the former mosque, which undoubtedly became too small and was integrated into the walls of its successor.

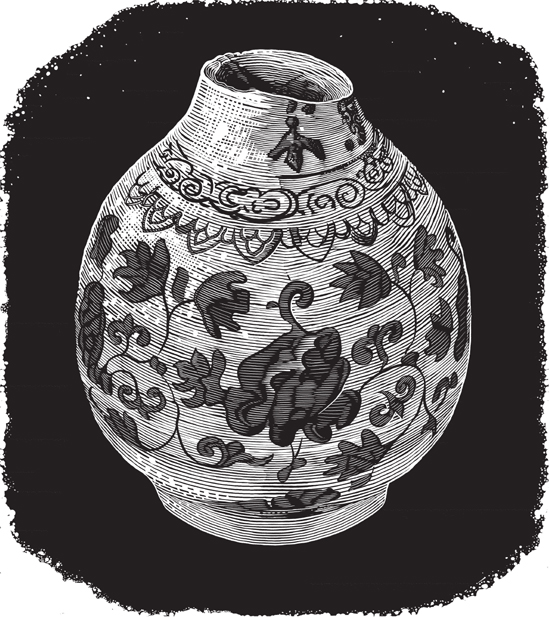

Neville Chittick, the British archaeologist who excavated Kilwa between 1958 and 1965, designated the archaeological levels associated with the mosque’s enlargement and the construction or reconstruction of the “large castle” as “period III.” This period corresponds to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. From the archaeological point of view, this monumental architecture marks a sharp break from the former periods. Most of the city, however, consisted of rectangular wattle-and-daub dwellings on wooden poles sunk into a foundation made from blocks of coralline limestone. Most of the coins found on-site date to this period, silver dirhams* and bronze divisional coins (dinars* were rare) struck by a dynasty of sultans called the Mahdalî. The excavations also revealed an abundance of imported glass beads, while Chinese porcelain, the classic blue and white and greenware, predominated among foreign ceramics. The beginning of this period is equally marked by a clear shift in the assemblage of local pottery; the underlying archaeological levels in fact reveal a production almost entirely distinct, notably a type of red-painted open bowl common on the Swahili coast. The levels corresponding to period II (thirteenth century) contained bronze coins, plus a small number of silver ones, issued by a previous dynasty called the “Shirazi.” (It is not necessary to see in this anything other than a mythical link with the city of Shiraz in Persia.) The original mosque is evidence of a significant Muslim community. We have even found distinctly Muslim tombs. The material imported in this period included Islamic ceramics from the Persian Gulf and silverware made from chloritoschiste, a soft rock from Madagascar. Madreporic limestone masonry blocks cut into fossilized coral, as well as the use of lime as mortar and flooring, were developed over the course of this period. Crucibles indicate that copper was worked there, probably imported.

No solid construction exists from the earlier archaeological phases, grouped together as period I. Nor was there a mosque, although if a mosque was ever erected in wattle and daub,* it probably would have escaped the attention of archaeologists. Still, no evidence for the existence of an established Muslim community has been found. Which doesn’t mean there were no Muslim individuals, foreigners established more or less permanently, or even local adherents; on the contrary, a stone fragment bearing an Arabic inscription indicates their presence in period Ib, around the eleventh and twelfth centuries. At that time cornelian beads were imported from India. But the site, where the remains of only wattle-and-daub dwellings have been detected, on the whole shows few signs of intense commercial activity—at least with overseas trading partners. Fragments of tuyeres and slags bear witness to an iron industry of limited scope. The iron ore certainly had to be imported, but from the neighboring continent. The large number of cowries* found in these levels is perhaps evidence of an industry whose products were intended to be sent in the opposite direction. The same is true of marine shell beads whose local production is attested by the remains of sandstone polishers. The island’s inhabitants grew and ground sorghum, but it is their taste for mollusks that has left the most traces. The shell middens are the best snapshot we have of the economy practiced by the island’s ancient occupants, perhaps from the ninth century: mixed with shards of local ceramics, they make up the bottom of the stratigraphic sequence, right where it meets virgin sand. Kilwa’s inhabitants thus were simple fishermen. But as pleasant as the environment may be, it does not on its own explain why people settled here. Perhaps one should add that shards of so-called Sasanid pottery—more rightly designated as Islamic (Abbasid)—with its typical lead glaze, were found, though in small quantity, in the deepest archaeological strata. It therefore can’t be said that there was settlement here long before the connection with the Islamic world. Indeed, settlement began at the same time the area was experiencing the first shock waves of this merchant activity. There can be no trade, however modest it may be at the beginning, without people going onto the beach to take part in the exchange. It was these encounters, and the opportunities they created, that made it possible to establish the settlement and delimit its function: commercial contact.

The accounts of the founding of Kilwa, of which we possess versions from the seventeenth century on, are half history, half legend. They insist on the foreign origin of the city’s royal and commercial elites. This is, of course, an elite point of view. The archaeological data have often intensified the importance of this foreign character, a flaw explained by the role imported objects, generally luxury goods, have played in the chronological assignment of the different archaeological periods identified in the site’s stratigraphic deposits. But archaeology also tells us another story, a story about a population of fishermen that was capable of ironworking. The latter skill was the mark of Bantu-speaking agricultural societies, which disseminated metallurgy in the southern half of the continent during the first millennium of our era. At that time, the inhabitants of Kilwa still looked to the continent: they exported there. It was only at the dawn of the second millennium of our era, then decisively in the thirteenth century, that the islanders, or a group of them, turned toward the open sea and catalyzed long-distance commerce. The evolution of their role in this commerce has left traces: first the simple evidence of arriving merchandise—Kilwa was a remote stopover for ships from all over the Arabian Peninsula, indeed, from even farther still. Traces, of an archaeological nature, of course, but which need to be interpreted as markers of identity, indications of which were not only imported as material goods but also adopted in practice and ideas: permanent architecture that made use of locally available materials; the Muslim religion; the use of luxury dishes; coins struck with the names of kings, the sole sub-Saharan example from the Middle Ages. Here indeed are witnesses to a repertoire of values, tastes, and beliefs that took root among local elites and allowed them to recognize themselves in others of their status, to communicate and culturally join with them. They constituted the features of a culture that created the sense of belonging to cities before cities existed.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

An inventory of the Kilwa Bay archaeological sites, with observations on the recent restorations, has been published by Stéphane Pradines and Pierre Blanchard, “Kilwa al-Mulûk. Premier bilan des travaux de conservation-restauration et des fouilles archéologiques dans la baie de Kilwa, Tanzanie,” Annales Islamologiques 39 (2005): 25–80; the article is accompanied by a rich iconographic dossier, notably high-quality maps and cross sections. It can be used in conjunction with John Sutton, “Kilwa: A History of the Ancient Swahili Town, with a Guide to the Monuments of Kilwa Kisiwani and Adjacent Islands,” Azania 33 (1998): 113–169. The archaeological publication of reference on Kilwa is Neville Chittick’s monograph, Kilwa: An Islamic Trading City on the East African Coast, 2 vols. (Nairobi: British Institute in Eastern Africa, 1974). The information about the stratigraphic levels presented in this chapter derives from this work. For a remarkable architectural study of the built remains of Kilwa, including high-quality maps and layouts, see Peter Garlake, The Early Islamic Architecture of the East African Coast (Nairobi: Oxford University Press, 1966), passim. Derek Nurse and Thomas Spear comment on the stratigraphy of several Swahili sites in The Swahili: Reconstructing the History and Language of an African Society, 800–1500 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985), pp. 16–22, which rightly insists on the important transformations that occurred in the thirteenth century in the architectural techniques and urban plans of Swahili cities. By distinguishing the Mahdalî from the Ahdali, a name that seems to belong to another regional dynasty, I part with Chittick and subscribe to the opinion put forth notably by Mark Horton and John Middleton, The Swahili (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2000), passim. From an abundant literature on the site of Kilwa, we should mention the study by S. Pradines, “L’île de Sanjé ya Kati (Kilwa, Tanzanie): un mythe shirâzi bien réel,” Azania 41 (2009): 1–25, which, despite espousing a heterodox point of view on the beginning of the site’s stratigraphy, offers a very useful overview of the state of the art.