CHAPTER 24

The Sultan and the Sea

Coast of Present-Day Senegal or Gambia, around 1312

The titles alone of books and articles devoted to a supposed African settlement of pre-Columbian America could fill a whole book. This bibliography can be divided into two sections. The first, largely produced by Europeans, especially in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, sought to demonstrate that Mesoamerican civilizations owed their rise to an original seed transmitted by migration from pharaonic Egypt, mother of civilizations, and were therefore linked to what contemporaries considered the glorious civilizations of the ancient Mediterranean. The second, produced mostly by African Americans and Africans in the second half of the twentieth century, desired to believe roughly the same thing, but with the premise that Egypt was a black civilization, and the implication that credit for having been the cradle of all civilization redounded to Africa. “Eurocentrism” against “Afrocentrism”: a battle of ideologies that conceals a war over memory. It is summed up well by the question “Who owns ancient Egypt?”

There is not the slightest bit of evidence to support the idea of an extra-American origin for the Olmec, Mayan, Toltec, or Aztec civilizations. Pairs of similar phenomena will always be compared; it’s the strategy of a number of authors who find things that resemble each other and see in them something more than mere “coincidence”: the pyramids of Egypt and the pyramids of Mexico, a Mayan glyph and a Saharan rock engraving, a monumental Olmec statue and an African face. Attention is especially given to the slightest trace of direct contact between the two continents before the fateful date of 1492. If there had been Vikings in the “Vinland” of the ancient Icelandic sagas, that is to say Newfoundland, before Christopher Columbus, and they settled there for at least several decades during the eleventh century, why couldn’t African adventurers have also reached the New World, preferably its central and southern part (since it was here that cultural forms best perceived as civilizations developed)? Such an episode, if it really happened, does not a “civilizing hero” make, no more than in the case of the Vikings (the voyage needed to have unleashed a continuous and irreversible movement of settlers); but why not discoverers?

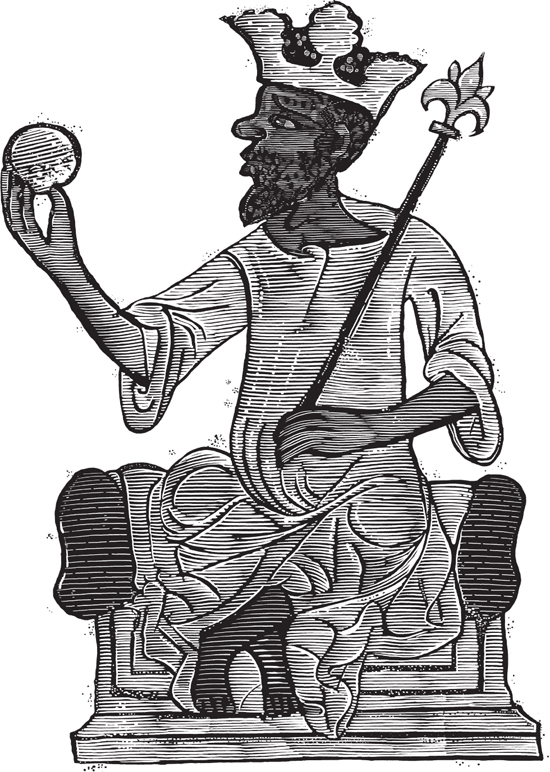

Yet there is indeed a story that seems to substantiate this hypothesis. It is related by Ibn Fadl Allâh al-Umarî, who was for a time, before he fell out of favor with the sultan, secretary of the Mamluk chancery in Egypt, and later, more famously, an encyclopedist very curious about the lands of sub-Saharan Africa. Al-Umarî, who wrote in the 1340s, took this story from the emir Abû l-Hasan Alî, who was governor of Cairo when Sultan Mûsâ of Mâli passed through the Egyptian capital on his pilgrimage to Mecca in the year 724 of the Hijra, that is, 1324 CE. The emir was full of anecdotes about the sultan. Once he asked him how he came to power. Al-Umarî, who heard the tale, preserved the monarch’s response.

“We belong,” said Mûsâ, “to a house which hands on the kingship by inheritance. The king who was my predecessor did not believe that it was impossible to discover the furthest limit of the Atlantic Ocean and wished vehemently to do so. He equipped 200 ships filled with men and the same number equipped with gold, water, and provisions enough to last them for years, and said to the man deputed to lead them: ‘Do not return until you reach the end of it or your provisions and water give out.’ They departed and a long time passed before anyone came back. Then one ship returned and we asked the captain what news they brought. He said, ‘Yes, O Sultan, we travelled for a long time until there appeared in the open sea [as it were] a river with a powerful current. Mine was the last of those ships. The [other] ships went on ahead but when they reached that place they did not return and no more was seen of them and we do not know what became of them. As for me, I went about at once and did not enter that river.’ But the sultan disbelieved him.

“Then that sultan got ready 2,000 ships, 1,000 for himself and the men whom he took with him and 1,000 for water and provisions. He left me to deputize for him and embarked on the Atlantic Ocean with his men. That was the last we saw of him and all those who were with him, and so I became king in my own right.”

The story speaks to us of a maritime expedition, a fleet of small boats that never returned—perhaps because, one can imagine, one may want to believe, it had reached the opposite shore. Are these the real discoverers? And since they were surely not just a handful of people at landfall, must they have transmitted some aspects of African civilizations across the Atlantic? And since they were capable of doing it once, had they not been able to do it before? But note that the story doesn’t tell us about a continent at the end of the ocean. No one in the chain of informants who participated in the elaboration and transmission of this account evoked a land located on the other coast of the Atlantic. Given that the sultan seemed so intent on proving that the crossing was possible, it is therefore quite clear that the idea that there was something at the other “end” of the ocean rather than nothing at all (a chasm, the edge of the world, darkness) was a theory that had not yet been validated by experience: no one had returned to vouch for it. Yet if they really had taken place, the expeditions of four hundred and two thousand small boats did not return, and if any discovery was made, it wasn’t known. To discover something, one has to reach somewhere; to have discovered something, one has to come back to where one started.

Never mind that Raymond Mauny, a famous French historian of Africa, believed he had shown definitively that such an expedition was impossible given the practical conditions of the time. The expedition of Mûsâ’s predecessor is to be situated, to paraphrase Mauny, in a world of paddled canoes: a world with no tradition of maritime sailing, either along the coast or on the high seas, which had never settled the Atlantic archipelagos (Cape Verde was not inhabited when the Portuguese arrived), and which was ignorant of wind patterns and currents. To use Mauny’s expression, it was only a failed attempt that falls into the “martyrology of maritime discovery.” But if his demonstration has convinced only those who wanted to be convinced, it is because it’s an almost impossible task to prove that something did not happen.

Fourteenth-century Mâli ( 26, 28, 29) was a vast kingdom—it is sometimes called an empire since its Muslim monarch had several kings as vassals, kings whom he had either conquered or forced to pay him homage by some other means. Among them was a monarch whose realm bordered the Atlantic coast between the Senegal and Gambia Rivers. It was the empire’s maritime window, certainly very far from the centers of power in the Malian savanna. But the country’s merchant and itinerant elites surely knew this littoral province, and so the western sea was not unknown to people from the heartland of Mâli. Whether the expedition took place or not, we are definitely talking about what is called the Atlantic Ocean today, and not about other bodies of water, allegorical or real (“sea” is a word used in many languages, including Arabic, to designate lakes). Maybe this story was an allusion to Arab maritime voyages of the time transmitted by foreign ulamas* who traversed the land in order to convert people to Islam? But there were scarcely any. Contemporaneous geographers reveal their ignorance about all things oceanic, and those who were really knowledgeable (i.e., sailors) were too few to venture along the Atlantic coasts south of Morocco; as for setting sail on the open sea, they probably did not do so, and consequently were unaware of the Canary Islands and Madeira. There was also the legend associated with Uqba ibn Nâfi, the conqueror of North Africa who was credited in many places with all sorts of miracles (

26, 28, 29) was a vast kingdom—it is sometimes called an empire since its Muslim monarch had several kings as vassals, kings whom he had either conquered or forced to pay him homage by some other means. Among them was a monarch whose realm bordered the Atlantic coast between the Senegal and Gambia Rivers. It was the empire’s maritime window, certainly very far from the centers of power in the Malian savanna. But the country’s merchant and itinerant elites surely knew this littoral province, and so the western sea was not unknown to people from the heartland of Mâli. Whether the expedition took place or not, we are definitely talking about what is called the Atlantic Ocean today, and not about other bodies of water, allegorical or real (“sea” is a word used in many languages, including Arabic, to designate lakes). Maybe this story was an allusion to Arab maritime voyages of the time transmitted by foreign ulamas* who traversed the land in order to convert people to Islam? But there were scarcely any. Contemporaneous geographers reveal their ignorance about all things oceanic, and those who were really knowledgeable (i.e., sailors) were too few to venture along the Atlantic coasts south of Morocco; as for setting sail on the open sea, they probably did not do so, and consequently were unaware of the Canary Islands and Madeira. There was also the legend associated with Uqba ibn Nâfi, the conqueror of North Africa who was credited in many places with all sorts of miracles ( 5); the narrative of his conquests may have circulated in Sahelian countries. It says that, having entered Africa by way of Egypt, he reached Sous on Morocco’s Atlantic coast. There he rode his horse into the sea, calling God to witness that he would have continued his path if the continent had extended to the west. Would the sultan of Mâli have remembered this scene, would he have tried to reenact it, as if to showcase both his historical accomplishment as a Muslim monarch and the political and religious project his ships carried with them? Calmly recounted by Mûsâ, his immediate successor, to a high-ranking official of Mamluk Egypt, the anecdote was infused with a valuable diplomatic message: I spring from a dynasty so devout that it claims to carry Islam beyond the ocean and to die a martyr’s death while doing so.

5); the narrative of his conquests may have circulated in Sahelian countries. It says that, having entered Africa by way of Egypt, he reached Sous on Morocco’s Atlantic coast. There he rode his horse into the sea, calling God to witness that he would have continued his path if the continent had extended to the west. Would the sultan of Mâli have remembered this scene, would he have tried to reenact it, as if to showcase both his historical accomplishment as a Muslim monarch and the political and religious project his ships carried with them? Calmly recounted by Mûsâ, his immediate successor, to a high-ranking official of Mamluk Egypt, the anecdote was infused with a valuable diplomatic message: I spring from a dynasty so devout that it claims to carry Islam beyond the ocean and to die a martyr’s death while doing so.

But, truth be told, there are reasons to doubt that this is really what the text is talking about, and when we reconsider its tenor, it certainly looks as though the anecdote must have inspired envy in those who heard about an enterprise so obviously devoid of interest and perhaps even marked by excessive vanity. However, the hypothesis has the merit of bringing us back to the literal meaning of the text. The sultan responded roughly as follows: “We belong to a house which hands on the kingship by inheritance. The king who was my predecessor did not believe that it was impossible to discover the furthest limit of the Atlantic Ocean. He wished to do so and failed. And so I became king in my own right.” In this story, which is first of all the story of a royal succession, there is perhaps something more profound and interesting than a catalyst for quarrels over precedence when it comes to crossing the Atlantic.

We often read that Mûsâ’s unfortunate predecessor was called Abû Bakr or Abu-Bakari. This was absolutely false, even though author after author diligently repeated it. This erroneous idea originated with a misunderstanding of the text of the famous historian Ibn Khaldûn that recounted the genealogy of the sultans of Mâli. The correct reading is that Abû Bakr was Mûsâ’s father, but not that he preceded his son on the throne. Mûsâ’s predecessor as sultan of Mâli was named Muhammad; he belonged to another branch of the dynasty, which had passed on the title from father to son since the time of the line’s progenitor, Mâri-Djâta, in the mid-thirteenth century. It was Muhammad whom Mûsâ succeeded around 1312. These details are important, for they signify that Mûsâ’s accession had brought another branch of the ruling dynasty to power. The story of the maritime expedition has perhaps something to do with the succession, which was certainly not peaceful inasmuch as Mûsâ issued from a collateral branch, and which couldn’t help but raise grave problems of legitimacy. The account Mûsâ gave of his accession to power is perhaps not to be understood as the seemingly off-topic narration of a maritime expedition, but as the reasoning behind his legitimate rule. He began his story with the words “We belong to a house which hands on the kingship by inheritance.” Thus we should take him at his word and listen to how the kingship was inherited.

There is always a risk, as mentioned above, when making comparisons. But let’s do it anyway, while remaining cognizant of its limitations, by bringing together several pieces of a puzzle, which will make it possible to illuminate a practice encountered in several African societies.

There are several myths about the origin of the kingdom of Loango, which flourished in central Africa, in what is today the western part of the Republic of Congo and the Angolese enclave of Cabinda, from the sixteenth century on. One of these myths evoked the civilizing hero, who is credited with teaching humanity how to make fire and increase fertility. He also introduced the institution of monarchy. Having reached the mouth of the river he was sailing on, he appeared to the inhabitants to be coming from the sea. They acknowledged him as king. Another recounted the origins of the kingdom’s second dynasty. The people could no longer tolerate their monarchs’ misrule and overthrew them; they sought a foundress for a new royal line. She was discovered in the forest, a young Pygmy girl, a member of a population endowed with strange, sacral attributes. She was accompanied to the seashore, then made to sail a bit farther to the kingdom promised to her descendants. She married and her son became the first king. In these two cases, the detour to the sea is synonymous with recognition or perhaps the ordeal par excellence; carried out under the beneficent aegis of a rain deity, it legitimated the new king, especially in the precise case of a dynastic void.

Let’s turn now to what was perhaps southern Somalia or northern Kenya a few centuries earlier. In 922, a storm tossed ashore a ship full of Omani merchants bound for Kanbalu on the coast of Zanj. Nowhere near a familiar port, the men were almost certain, they believed, to be eaten. But the African population was welcoming and its young king favorable to trade. As they were leaving, the ungrateful Arabs kidnapped the king and took him as a slave (at the same time, moreover, some two hundred other individuals were purchased locally). The king would be sold at Oman in the southeastern corner of the Arabian Peninsula. A few years later, the same merchants suffered another storm in the same vicinity, which, to add insult to injury, tossed their boat onto the same stretch of coast. To their great surprise, they met the king, who recognized them and gave them a cold reception. Ultimately magnanimous, he pardoned them and told his story. Taken to Baghdad after he had been sold at Oman, the young man had learned Arabic and became a Muslim. He then escaped, going first to Mecca, then to Cairo, and eventually managed to find the beach where he had been seized. He was afraid to disembark, for he believed that the new king of the country would quickly have him killed. But the seers had warned against taking a new king until there was news of the missing one. He thus arrived at the palace, where he was recognized and warmly welcomed. This tale is certainly full of the folklore of Arab and Persian sailors, but a story is embedded here that we can think of as African. It matters little whether the adventure really happened or was just a myth; what catches our attention is that a long journey across the sea was necessary to see our young man confirmed twice over: as king, by his people, and as Muslim, by the traveling merchants.

There are certainly elements missing here—historical, ethnological, mythological—that need to be found. But those we have are already enough to enable us to formulate a hypothesis: that a common mythology of the origin of royalty existed in several regions of Africa, perhaps a common ritual for the investiture of a new king during times of crisis. Whether this served to describe how authority emerged from a power vacuum, or prescribes a ritual the king must undertake to be acknowledged as ruler, it was the detour by the ocean, father of all waters, that made the monarch.

Did the expeditions of Muhammad take place? Perhaps not, if we take Mûsâ’s account of them to be only the story of a dynastic crisis expressed in the political language of the kingdom of Mâli. But if it did, it’s a safe bet that his political act—whose precise religious frame we struggle to recognize: royal initiation, purification ritual, trial by ordeal?—was designed to challenge the ocean and return from it with a reinforced claim to the throne. It was a failure. But there was a winner: the storyteller himself, King Mûsâ.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

The sultan’s story as recounted by al-Umarî is taken from Nehemia Levtzion and J.F.P. Hopkins (eds.), Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History (Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener, 2000), pp. 268–269. Regarding the Afrocentric theory of a civilizing settlement of America by Africans, see, among a huge literature, Ivan Van Sertima, They Came before Columbus (New York: Random House, 1976). The question “Who owns ancient Egypt?” is borrowed from the title of the excellent review article by Wyatt MacGaffey, “Who Owns Ancient Egypt?” Journal of African History 32 (1991): 515–519. Raymond Mauny’s reflections on the supposed maritime expedition of Mûsâ’s predecessor are laid out in Navigations médiévales sur les côtes sahariennes antérieures à la découverte portugaise (1434) (Lisbon: Centro de Estudos históricos ultramarinos, 1960). The most up-to-date study on the genealogy of the sultans of Mâli remains that of Nehemia Levtzion, “The Thirteenth and Fourteenth-Century Kings of Mali,” Journal of African History 4 (1963): 341–353. The Loango myths come from Luc de Heusch, Le Roi de Kongo et les monstres sacrés (Paris: Gallimard, 2000), pp. 44–48. The story of the Omani sailors, which appears in a ninth-century work by a Persian navigator, Buzurg ibn Shahriyâr, has been translated into English by G.S.P. Freeman-Grenville, The East African Coast (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962), pp. 9–13.