CHAPTER 29

The King’s Speech

In Mâli City, Capital of the Kingdom of Mâli,

from June 1352 to February 1353

“He is the sultan mansâ Sulaymân. Mansâ means ‘sultan’ and Sulaymân is his name. He is a miserly king from whom no great donation is to be expected.” With these words, Ibn Battûta conjured up the reigning sultan at the time of his journey. One day he was told that the sultan had just sent him the welcome gift, what he hoped were clothes and a present. He went with the message-bearer: “I got up, thinking that it would be robes of honor and money, but behold! It was three loaves of bread and a piece of beef fried in ghartî [shea* butter] and a gourd containing curdled milk. When I saw it I laughed, and was long astonished at their feeble intellect and their respect for mean things.”

Throughout his life, say, after he reached the age of twenty, Ibn Battûta was an insatiable freeloader, living off the largesse of the sultans and religious leaders of the Islamic world. Born in 1304 at Tangier on the Strait of Gibraltar, he crossed large parts of the Islamic world: he made the pilgrimage to Mecca several times; spent a few years in India, where he resided at the court of the sultan of Delhi; and even ventured as far as the Maldives archipelago, where he served as a judge. If visiting the entire Islamic world was not the goal of his travels, describing the totality of that world was, in any event, the ambition of his written work. This encyclopedic project, which painted landscapes of the Islamic world’s important places as well as portraits of its elites, was so important that he had to take certain liberties with the truth. Thus the reality of his “travels” to China, the Volga River valley, or East Africa can be doubted. We can even be suspicious about Mâli: the description seems thin for an eight-month sojourn. Judging from what Ibn Battûta experiences, enjoys, and describes in the rest of his book, his description of Mâli is missing everything that shouldn’t be missing: daily life, the climate, entertainment, the surrounding countryside, women. We find there only what we were sure to find there: the moral portrait of the sultan, the list of the distinguished persons, the protocol, descriptions of the audiences and grand ceremonies. But let’s not conclude from the story’s uncertainties that the trip was impossible, nor from the trip’s impossibility that the story was entirely false. The testimony’s inadequacy can result from other factors beyond feigned firsthand experience; and in any case the lack of firsthand experience can be mitigated by good sources. Let’s proceed as if everything related by Ibn Battûta had been seen by him.

Ibn Battûta didn’t bother to describe for us the exact route leading from Oualata ( 26) in southern Mauritania to the capital of Mâli. We know only that one had to go south. “The road has many trees. Its trees are of great age and vast size, so that a whole caravan may get shelter in the shade of one of them.” He is certainly describing baobabs here, whose giant silhouettes are characteristic of the arboreal savanna. From his description of local products we can equally recognize the shea tree,* whose ground-up kernel produced a butter that could be used for frying, ointments, and, as Ibn Battûta informs us, coating dwellings. His caravan passed through many well-supplied villages. Ten days after leaving Oualata, they arrived at Zâghari, a large village home to black merchants, the Wangâra (

26) in southern Mauritania to the capital of Mâli. We know only that one had to go south. “The road has many trees. Its trees are of great age and vast size, so that a whole caravan may get shelter in the shade of one of them.” He is certainly describing baobabs here, whose giant silhouettes are characteristic of the arboreal savanna. From his description of local products we can equally recognize the shea tree,* whose ground-up kernel produced a butter that could be used for frying, ointments, and, as Ibn Battûta informs us, coating dwellings. His caravan passed through many well-supplied villages. Ten days after leaving Oualata, they arrived at Zâghari, a large village home to black merchants, the Wangâra ( 17), and some whites, also Muslims, but schismatics, the Kharijites (

17), and some whites, also Muslims, but schismatics, the Kharijites ( 5). Next came Kârsakhu, a city near a “great river,” which, he says, flowed in the direction of Timbuktu. Finally they crossed another river, the Sansara. Ibn Battûta and his companions entered the city of Mâli, “capital of the king of the Land of the Blacks.” The fast-paced journey had lasted twenty-four days. The problem is that with the exception of the starting point, Oualata, no name is recognizable to us.

5). Next came Kârsakhu, a city near a “great river,” which, he says, flowed in the direction of Timbuktu. Finally they crossed another river, the Sansara. Ibn Battûta and his companions entered the city of Mâli, “capital of the king of the Land of the Blacks.” The fast-paced journey had lasted twenty-four days. The problem is that with the exception of the starting point, Oualata, no name is recognizable to us.

Starting with what is known from the text, scholars have played around a lot with maps and compasses. Twenty-four days from Oualata, depending on whether one goes southeast rather than southwest, on what rivers one crosses, on how fast one travels, certainly on one’s opinion about the capital’s conceivable locations, and finally on the degree of trust one has in toponymic approximations, one determines that the capital of medieval Mâli has been found in the small village of Niani located in the east of present-day Guinea-Conakry; or in a village named Mali on the banks of the upper Gambia in modern Senegal; or else somewhere halfway between Bamako and Niamina on the left bank of the Niger, in present-day Mali. Three hypothetical locations in three different modern countries. One might think the enigma can be resolved by positing that the empire of Mali had several successive or simultaneous capitals, a credible hypothesis but one irrelevant in accounting for what Ibn Battûta spoke about. It is instructive that the zone swept up in these hypotheses covers a region approximately eight hundred kilometers in length by four hundred kilometers in width. We would be in a similar quandary with Europe if we had only the text of a tenth-century Andalusian traveler to help us decide whether the capital of the Carolingian Empire was located at Aix-la-Chapelle, Aix-les-Bains, or Aix-en-Provence.

But if the search for the city’s location has so far been unsuccessful, that is not at all the case when it comes to visualizing its spatial organization. One can at least attempt a description of Mâli City’s most significant features based on Ibn Battûta’s narrative of the different ceremonies and festivities he attended there—ceremonies that furnished yet more material for him to compare with the various displays of royal pomp he had seen on his travels.

First of all we discover a palace; or, rather, we catch a glimpse of it. Only the royal family and the slaves who attended them could enter it, and we thus have no description of its appearance. It is thought that it was a complex made up of several enclosed spaces; it must have had clusters of dwellings forming living quarters for the king, his family, and dependents, and spaces for royal offices and regalian functions. It was certainly a vast architectural ensemble in banco.* In a corner of this complex lay a domed room. Perhaps it was this room that had been built a quarter century earlier by mansâ Mûsâ ( 28), Sulaymân’s brother. Ibn Battûta simply says that it was a domed, one-room building. It seems there was only one door, which opened onto the interior of the palace. The exterior side, overlooking the esplanade called a mashwâr, an Arabic term that in North Africa designated a place for public ceremonies, was pierced only by windows. This facade was remarkable; it was decorated with two registers, each made up of three wooden windows. The windows of the upper register were covered with sheets of silver, those of the lower register with sheets of gold or gilded silver. The windows were grilled and covered with curtains. The mashwâr isn’t described, but based on what took place there and the way it took place there, we understand that it was an elongated space facing the domed room. It was certainly enclosed by a wall. At the other end, symmetrically facing the domed room was a portal that closed the mashwâr. A tree-lined street extended the mashwâr. We know that there was also a mosque, in all likelihood located in the same area, perhaps directly accessible from the palace and the mashwâr.

28), Sulaymân’s brother. Ibn Battûta simply says that it was a domed, one-room building. It seems there was only one door, which opened onto the interior of the palace. The exterior side, overlooking the esplanade called a mashwâr, an Arabic term that in North Africa designated a place for public ceremonies, was pierced only by windows. This facade was remarkable; it was decorated with two registers, each made up of three wooden windows. The windows of the upper register were covered with sheets of silver, those of the lower register with sheets of gold or gilded silver. The windows were grilled and covered with curtains. The mashwâr isn’t described, but based on what took place there and the way it took place there, we understand that it was an elongated space facing the domed room. It was certainly enclosed by a wall. At the other end, symmetrically facing the domed room was a portal that closed the mashwâr. A tree-lined street extended the mashwâr. We know that there was also a mosque, in all likelihood located in the same area, perhaps directly accessible from the palace and the mashwâr.

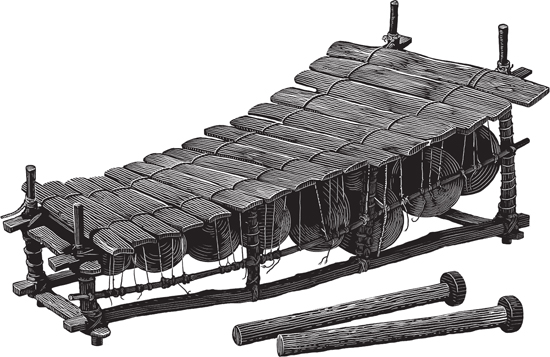

At Mâli City, Ibn Battûta attended ceremonies, several of which he classified as audiences. In the strict sense, only those meetings where the sultan himself sat in the domed room warrant this appellation. On the days “[w]hen he is sitting they hang out from the window of one of the arches a silken cord to which is attached a patterned Egyptian kerchief. When the people see the kerchief drums are beaten and trumpets are sounded.” It was the signal for a precise arrangement that Ibn Battûta observed from the mashwâr, where he took his place among the other residents of the city who whispered to him the meaning of this or that gesture. Three hundred armed men, some carrying bows, others lances and shields, came forth from the palace and lined up on either side of the esplanade. This was the king’s slave bodyguard. Then two saddled and bridled horses were introduced, along with two rams and the sultan’s lieutenant, his stand-in, so to speak. This was the king’s symbolic entrance. Next came the traditional chiefs and Muslim religious leaders, that is, the “civil” notables. Soldiers, on foot and on horseback, were ranged outside the mashwâr, each company behind its emir. The men bore “lances and bows, drums and trumpets. Their trumpets (bûq) are made out of elephant-tusks and their [other] musical instruments are made out of reeds and gourds and are played with a striker (sattâ‘a) and have a wonderful sound.” The eunuchs and foreigners were also assembled there. A curiously dressed man stood at the gate of the mashwâr. Ibn Battûta, who met him at the very beginning of his sojourn in Mâli, says that this was the sultan’s interpreter; his name was Dûghâ. On that day, “[he was wearing] fine garments of silk brocade… and other materials, and on his head a turban with fringes which they have a novel way of winding. Round his waist he has a sword with a golden sheath and on his feet boots and spurs. No-one but him wears boots on that day. In his hand he has two short lances, one of gold and the other of silver, with iron tips.”

Audiences took place in the following fashion. One of the king’s simple subjects comes to make a request; we do not know what he asks, but we know how he asks: he takes off his clothes, dons rags, and crawls toward the sultan. When the king speaks to him, the man goes down on his knees. When the king finishes speaking, the suppliant grabs dust from the ground and tosses it on his head and back. Next is a man of the highest rank who comes to boast of his merits; if someone agrees with his boasts, he makes it known by the twang of his bowstring. If the sultan makes a speech, everyone removes his turban. Finally it’s the turn of a jurist who comes from a distant province to bear witness to injustice. He is a wise man. Locusts, he says, have descended upon the land. A holy man, an ulama,* was sent to investigate and the locusts spoke to him: “God sends us to the country in which there is much oppression in order to spoil its crops.” No one would have dared to make such a public criticism, but was anyone going to reproach the locusts?

The spatial arrangement and the proceedings of the royal audiences in Mali reveal a curious aspect: they kept the king hidden. Let’s start by saying that this is a feature of royalty that we recognize up until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in many African kingdoms, especially those of the Sahel. To say that what we see here is an indication of a sacred monarchy is to speak too quickly. For the king was not hidden from view in all he did or on every occasion. Furthermore, he was not absent; on the contrary, he was eminently present, his physical occultation accentuating his royalty. At Mâli City, his presence is affirmed in multiple ways: by the curtains drawn over the windows, the kerchief passed through the window grille, the music, the stand-in, the royal animals, and the entire ceremonial that showcased the humility of those who dared to brave the royal presence. There is nothing here of divine kingship, but rather the affirmation, remarkable for the sophistication of its mise-en-scène, of the presence of a political body that augmented as far as it concealed the individual body that personified it.

However, the king was not always removed from sight. There were other public ceremonies where everyone could see him; each Friday he went to the mosque and prayed with the faithful. On many other occasions, the people—Muslim or non-Muslim, distinguished or of low birth, aggrieved or satisfied—could see him exercise his kingship. All in all, it was only during audiences that the man who exercised sovereignty was hidden from the eyes of his fellow human beings. On those days, the asymmetry of gazes combined with an asymmetry of verbal exchange, which saw an authoritative way of speaking respond to a humble, measured, allegorical one and imposed on everyone, from paupers to the powerful, performances of the most striking debasement. It was not a dialogue, still less a deliberative assembly. It was a strange speech circulation system. Let’s take a closer look: petitioners didn’t address the sultan directly; they addressed a man who stood below the windows of the domed room. It was he who transmitted the case or request made in the dust outside to the sultan in his domed room; it was he who received the response and transmitted it toward the mashwâr, before the dignitaries who formed the sultan’s council. Should we call him the spokesman, the public crier? For all that, he was not the centerpiece of the system. That was Dûghâ, whom Ibn Battûta called the interpreter because he spoke Maninka and Arabic and could translate from one language to the other, but also, and perhaps especially, because he was the man who formulated the demands addressed to the sultan as well as the royal decisions in response. “Anyone who wishes to address the sultan addresses Dûghâ and Dûghâ addresses that man standing [under the windows] and that man standing addresses the sultan.” As long as it concerns something political, as is the case in such circumstances, speech has to be made public in a loud and clear voice.

No secrets, no demands murmured in low voices, no opinions influenced by favoritism. During these audiences where the sultan judged, honored, decreed—in short, governed—the requests and the decisions they elicited were publicly pronounced by Dûghâ. This flesh-and-blood man was, as it were, the minister of the word. The one who, on those days and in that place, was the ultimate source of law, remained invisible and silent.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

All citations from Ibn Battûta’s description of Mâli are taken from Nehemia Levtzion and J.F.P. Hopkins (eds.), Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History (Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener, 2000), pp. 286–294 (slightly modified on one occasion, about the curdled milk). On Ibn Battûta’s voyage to Mâli and the doubts that can be brought to bear on the subject, and on the journey’s narrative logic, see the article Bertrand Hirsch and I have written on the topic: “Voyage aux frontières du monde. Topologie, narration et jeux de miroir dans la Rihla de Ibn Battûta,” Afrique & Histoire 1 (2003): 75–122, which can be accessed online: https://www.cairn.info/revue-afrique-et-histoire-2003-1-p-75.htm. See also my article “Ibn Battuta, Muhammad ibn Abdullah,” in John Middleton and Joseph C. Miller (eds.), New Encyclopedia of Africa (Detroit: Thomson/Gale, 2008), 3:2; and my chapter “Trade and Travel in Africa’s Golden Global Age (700–1500),” in Dorothy Hodgson and Judith Byfeld (eds.), Global Africa into the Twenty-First Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017), pp. 17–26. The most accepted—and the most reliable, in my view—hypothesis for the location of the capital described by Ibn Battûta is that of John O. Hunwick of a location in present-day Mali, somewhere between Bamako and Niamina; it is presented in “The Mid-Fourteenth Century Capital of Mali,” Journal of African History 14 (1973): 195–206. But it should also be stressed that no discovery on the ground has as yet confirmed this hypothesis. Some still believe that the fourteenth-century capital of Mâli was at the site of Niani in Guinée-Conakry, which has been excavated by a Polish-Guinean team; see Władysław Filipowiak, Études archéologiques sur la capitale médiévale du Mali (Szczecin: Muzeum Narodowe, 1979). On the reservations one should have regarding the interpretation of these excavations, see my articles “Niani Redux: A Final Rejection of the Identification of the Site of Niani (Republic of Guinea) with the Capital of the Kingdom of Mali,” Palethnology 4 (2012): 235–252, http://blogs.univ-tlse2.fr/palethnologie/en/2012-10-fauvelle-aymar/, and “African Archaeology and the Chalk-Line Effect: A Consideration of Mâli and Sijilmâsa,” in Toby Green and Benedetta Rossi (eds.), Landscape, Sources and Intellectual Projects of the West African Past: Essays in Honour of Paulo Fernando de Moraes Farias (Leiden: Brill, in press). For an illustration of the vision that a merchant from the Islamic tradition, in this case a Jew from al-Andalus, had of ninth-century Europe, and the doubts that persist regarding the toponym AQSH, in which may possibly be recognized a city by the name of Aix (of which there are many in France and Germany), see André Miquel, “L’Europe occidentale dans la relation arabe d’Ibrâhim b. Ya‘qûb (Xe s.),” Annales. Économies, sociétés, civilisations 21 (1966): 1048–1064.