Chapter 4

Overcoming Weakness

In This Chapter

Persevering over personal character flaws

Dealing with bad influences

The saints we profile in this book weren’t perfect or sinless by any stretch of the imagination; they were normal human beings with the same temptations and foibles as anyone else. Some were weaker or more flawed than others, and they overcame their disadvantages through God’s grace.

In this chapter, we focus on some of these saints who had to vanquish various weaknesses in order to have a closer relationship with God.

St. Augustine (Playboy to Puritan)

Northern Africa (AD 354–AD 430)

Patron: theologians, reckless youth

Feast day: August 28

Augustine was the eldest of three children born to a pagan, Patricius, and his devout Christian wife, Monica (see the entry on St. Monica later in the chapter). He spent his youth living a wild and immodest life filled with indulgence and sin. In his autobiography (Confessions), Augustine told of sinning with gusto and breaking every one of the Ten Commandments, except the prohibition against murder. To make up for that one, he said, he broke the others even more often.

It wasn’t until he reached middle age and was accompanied by his illegitimate son, Adeodatus, that Augustine began to see the error of his ways. He abandoned the playboy culture and gravitated to the opposite pole of the heretical Manichaeans. Theirs was a dualistic philosophy holding that the physical, material world was evil. Only the spiritual, immaterial world was important and had value to Augustine at this time, so he embraced a life of sacrifice and denial.

The Manichaeans disdained marriage and children, as children were the fruit of sexual intercourse, and anything so physical had to be evil. Christianity bridged and healed the gap between Augustine’s two lives, and Bishop Ambrose in Milan convinced Augustine and his son to embrace Catholicism.

St. Camillus de Lellis (Compulsive Gambler)

Italy (1550–1614)

Beatified: 1742

Canonized: 1746

Patron: nurses, addicted gamblers

Feast day: July 14

Camillus was the son of a successful military officer and a mother who died when he was very young. He followed in his father’s footsteps and entered the military when he was of age. His father kept him busy, hiring out his services whenever someone needed a soldier.

Camillus didn’t have a stable or wholesome upbringing and thus lived a rebellious adolescence. Following once again in his father’s footsteps, he acquired a taste for heavy gambling and wagering, which often led to barroom brawls.

Once, when he and his father were traveling on foot to join the army in Venice, which was being raised to fight the Turks, both men fell terribly ill. Camillus’s father’s illness was the worse of the two, and he eventually succumbed to the illness. On his deathbed, seeing his disillusioned life pass before him, Camillus’s father asked for a priest and made a good confession, was anointed, and received the last rites. He died a repentant man.

Camillus, however, took a bit longer to see the error of his ways, joining a Franciscan monastery only after becoming totally destitute from gambling debts. At the monastery, he found that old habits truly do die hard. He often snuck out of the monastery to meet with old friends and engage in old habits, such as drinking to excess and gambling. His superiors at the monastery dismissed him, believing he wasn’t ready to commit to the monastic life.

Returning to his mercenary career, Camillus found little or no happiness. Remembering the peace his father had found, Camillus tried to reenter the Franciscan monastery, but his previous track record tarnished his reputation enough that he soon had to leave.

St. Dismas (Thief)

(first century AD)

Patron: reformed thieves/criminals

Feast day: March 25

Dismas is believed to be one of the two thieves between whom Jesus was crucified. He was the “good” or “repentant” thief who appeared remorseful of his sins and asked Jesus to “remember me when you come into your kingdom.” Jesus replied, “This very day you will be with me in paradise.”

Evidence does exist, however, of the devotion to St. Dismas: Many reformatories have been named in his honor as an homage to the belief that it’s possible to turn a new leaf and live a better life.

St. Jerome (Bad Temper)

Dalmatia (AD 340–AD 420)

Patron: anger management, Bible scholars, and translators

Feast day: September 30

Jerome was a brilliant scholar and linguist who was commissioned by Pope Damasus I to translate the Bible into one language (see Chapter 13). The Old Testament was written mostly in Hebrew, with several books in Greek, and the New Testament was written in Aramaic and Greek. Other than the academicians, the general populace of the Western Roman Empire was literate only in Latin.

Prior to being tasked with this monumental project, Jerome had spent a good part of his life battling his own demons. His Achilles’ heel was his quick temper; if verbal arguments didn’t get him into trouble, his writings did. A genius in his own right, Jerome got so absorbed in his research and work that he became detached from the social world. That’s where most of the contretemps began: He hated distractions while working on an important project, like translating the Bible into Latin.

The archetype of curmudgeons, Jerome didn’t take well to criticism or opposition and wasn’t anyone to tangle with. He responded to comments that he deemed unfair with tirades that would demean any notable adversary. Even St. Augustine, who admired Jerome’s high intellect, feared his vitriolic temper.

Knowing his own weakness and wanting to remove himself from temptation, Jerome found refuge living like a hermit away from people and avoiding people who annoyed him. He didn’t make excuses for his short temper, but he tried to adapt himself so that others wouldn’t become collateral victims of his wrath. Like an alcoholic who must avoid the bars, Jerome saw the benefit of retreating to his own oasis, where he wouldn’t be tempted to lose his patience or temper.

St. Mary Magdalene (Former Prostitute)

(first century AD)

Patron: wayward women

Feast day: July 22

The Scriptures identify Mary Magdalene by name only three times: as the woman from whom Jesus exorcized seven demons, as one of the women at the foot of Christ on the cross, and as the first to discover the risen Jesus at the tomb on the day of the Resurrection.

Pious tradition (common belief on a nondoctrinal matter) extended beyond Sacred Scripture and identified Mary Magdalene as the adulterous woman whom Jesus saved from being stoned to death when he said to her accusers, “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone.” Some also believed her to be the woman who washed Jesus’s feet with her tears, wiped them with her hair, and then anointed them with perfumed oil.

Jesus went beyond showing mercy and may have intervened on Mary Magdalene’s behalf, preventing her from being murdered because of her sinful lifestyle. Rather than being an insult, the “former prostitute” label demonstrates that a woman at the lowest social and spiritual realm — a woman who committed the very public sin of prostitution — could rise to the highest heights, serving as “apostle to the apostles” by announcing Christ’s Resurrection.

Biblical scholars still debate the issue — some insist that Mary wasn’t a prostitute or adulteress, and others contend that the circumstantial evidence says she was. The Church has never formally declared her occupation, but the late Archbishop Fulton Sheen, who had a popular TV show in the 1950s, thought that Mary’s dubious past was a romantic example of how much divine love can forgive: anyone and anything.

Mary also had the honor and privilege of being at the foot of the cross when Christ died on Good Friday. So far from being dismissed by the Church Fathers, Mary Magdalene became the premiere example of a sinner being redeemed and rising to great levels of holiness, thanks to the divine mercy of God.

Over the centuries, many “Magdalene” houses have been established to help save women from the abuse and exploitation of prostitution. The belief has always been that if someone as notorious as Mary Magdalene can turn her life around and become a devout disciple of the Lord, then, by God’s grace, anyone can follow in her footsteps.

St. Monica (Mother of a No-Good Son)

Northern Africa (AD 331–AD 387)

Patron: abused or neglected wives, mothers of wayward children

Feast day: August 27

St. Monica was the quintessence of patience. She was the wife of an abusive, cheating man, Patricius, who had a short fuse and a violent temper, in addition to a wandering eye. When he wasn’t arguing with Monica, he was cheating on her.

Monica also had to endure her horrible mother-in-law who lived with them — a stereotypical busybody who thrived on criticizing her son’s wife. Making matters worse was Monica’s lazy, irresponsible, reckless, and amoral son, Augustine. The eldest of three children, Augustine eventually moved in with his girlfriend without being married to her.

Despite their problems, Monica loved her family very much and wanted nothing less than their conversion to Christianity and lives of holiness and moral living.

After almost 30 years of perseverance and prayer, Monica saw her dreams realized: Augustine and his illegitimate son were baptized.

She followed Augustine when he left northern Africa for Rome, foiling an attempt he made to lose her by altering his route and going to Milan instead. In Milan, Augustine met St. Ambrose, who was the one to finally baptize Augustine and his son. (See his section earlier in the chapter for more on Augustine.)

St. Padre Pio (False Accusations)

Pietrelcina, Italy (1887–1968)

Beatified: 1999

Canonized: 2002

Patron: those falsely accused

Feast day: September 23

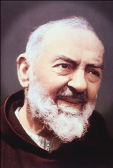

Although St. Pio (see Figure 4-1) became famous for having the stigmata — the miraculous appearance of the five wounds of Christ — on his hands and feet, he also gained notoriety by surviving the stigma of false accusations leveled against him. Though revered today as a holy man of God, St. Pio had enemies who at one point so twisted and distorted the facts that he was considered a devious fake.

Figure 4-1: St. Padre Pio ultimately triumphed over false accusations and the animosity of those who doubted his piety.

Born Francesco Forgione, St. Pio wanted to become a Capuchin monk — a branch of the Franciscan friars — which persuaded his father to emigrate to the United States to raise money for the seminary education of his son.

Ordained in 1910, he began going into trances while celebrating Mass, and he was often in a trance for nearly an hour. Although many, such as St. Catherine of Siena, considered this a sign of great sanctity, others complained that Pio’s masses took too long, and he was consequently ordered to keep the daily celebration to just 30 minutes.

The stigmata appeared eight years later, and Pio’s hands often bled while he conducted Mass. His parishioners witnessed the phenomenon and word spread quickly; large crowds came from all over Italy to attend a Mass celebrated by this saintly man.

Pio often spent 18 hours in the confessional and had the gift of discernment, which allowed him to read souls and tell penitents when they forgot (or intentionally omitted) a sin during confession. The number of pilgrims to visit him at San Giovanni Rotondo escalated dramatically.

The local bishop was suspicious of the Capuchin Franciscans and doubted the authenticity of Pio’s gifts. He thought that the religious community was profiting from the sales of religious goods to the pilgrims that visited. The bishop complained to what was then called the Holy Office, now known as the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (run by Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger before he was elected Pope Benedict XVI in 2005).

Both Pope Benedict XV and Pope Pius XI started Vatican investigations into Pio’s activities in the 1920s, and one papal physician, Franciscan Fr. Agostino Gemelli, accused Padre Pio of fabricating his stigmata by using carbonic acid. The mere allegation of fraud — despite the lack of due process or adjudication — led Church authorities to forbid Pio from receiving visitors, hearing confessions, or celebrating Mass in public.

The censures were lifted in 1933, but the suspicion remained, and many didn’t believe that Pio was an authentic stigmatist. Others, a large majority of the faithful, never doubted his sincerity. Area Communists tried to implicate him in financial malfeasance, but again, nothing was ever proved.

Another investigation by Pope John XXIII in the 1960s was also inconclusive, but some influential Vatican bureaucrats kept the scrutiny going. More accusations were cast against Pio, this time alleging sexual misconduct with some of his female devotees. Not only was no credible evidence discovered, but a thorough investigation exonerated Pio of all allegations. It took some time for his name to be cleared; Pio remained obedient through it all and quietly obeyed his supervisors, even when being unjustly punished.

When Pope Paul VI was seated in 1963, a Polish bishop, Karol Wojtyla, visited Pio. This bishop later became Pope John Paul II, who beatified Pio in 1999 and canonized him in 2002.