Chapter 16

Greek Fathers of the Church

In This Chapter

Fighting against Arianism and other heresies

Building the foundation of the Eastern Church

After the Roman Emperor Constantine (fourth century AD) established the imperial city of Constantinople (formerly Byzantium, currently Istanbul), he divided the empire into two parts, East and West. The Western half used the Latin language and the Eastern half used Greek. The Catholic Church was unofficially but culturally partitioned between East and West. There was one emperor and one pope but two flavors, so to speak.

So for several hundred years, Christianity was united under one roof, albeit with two traditions (Western-Latin and Eastern-Greek). By the 11th century (1054), though, the Great Schism had divided East and West into two separate churches — Catholic and Orthodox. Later, in the 17th century, several Eastern Orthodox communities came back into full communion with the pope in Rome, and they’re called Byzantine Catholics or Greek Catholics to distinguish them from the Latin Roman Catholics who lived in the West.

Just as learned men from the Western Church became known as the Latin Fathers of the Church (see Chapter 15), some equally brilliant scholars from the Eastern part of the Church became known as the Greek Fathers. In this chapter, we introduce you to these Greek Fathers of the Church, men who helped in the formation of the Eastern Catholic Church.

St. Athanasius of Alexandria

Alexandria, Egypt (AD 297–AD 373)

Feast day: May 2

As an early disciple of St. Alexander, Bishop of Alexandria, Athanasius learned right away how to defend the Orthodox teachings of the Catholic Church. Alexander was a primary adversary of the Arian heretics at the Council of Nicea in AD 325, and Athanasius, an ordained deacon, assisted Alexander there. Athanasius followed the lead of St. Alexander and vigorously denounced Arianism (heresy that denied the divinity of Christ) whenever he could. He was elected Patriarch of Alexandria in AD 326 following St. Alexander’s death.

Athanasius also wrote a lengthy creed, Quicumque vult (whosoever wishes to be saved), to formally address Church doctrine regarding the Holy Trinity and the errors of Arianism. The creed endorses the theology of a triune monotheism (one God in three persons); Trinitarianism is the foundation of Christianity, and anything less — Unitarianism or dualism, for instance — is not acceptable.

St. Basil the Great, Archbishop of Caesarea

Caesarea, Cappadocia (AD 329–AD 379)

Feast day: January 2

Basil grew up surrounded by strong faith: He was the son of St. Basil the Elder and St. Emmelia; the grandson of St. Macrina the Elder; and brother to SS. Gregory of Nyssa, Macrina the Younger, and Peter of Sebastea.

With such a family lineage, Basil showed holiness at an early age, cooking meals for the poor and raising money for them. Though members of nobility typically helped the needy indirectly through their servants, Basil preferred to “get his hands dirty” and practice his faith. He eventually became a monk and is considered the father of Eastern monasticism, just as St. Benedict was for the Latin, or Western, Church (see Chapter 15).

Basil was a champion of the teachings of Nicea (AD 325) and Constantinople I (AD 360), and as such, he boldly fought the heresy of Arianism. He was also a reformer when he became Bishop of Caesarea in AD 370 in that he punished anyone found guilty of simony — trying to buy or sell spiritual favors — and he demanded honesty and integrity from all his clergy. Basil’s followers were so fond of his service as bishop, preacher, and teacher that he was known as Basil the Great even before he died.

St. Clement of Alexandria

Athens, Greece (AD 150–AD 215)

Feast day: December 4

Clement was Origen’s teacher at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. He made a great contribution in applying Greek philosophical thought to the study, defense, and understanding of Christian theology.

SS. Cyril and Methodius

Cyril (Constantine): Thessalonica Greece (AD 827–AD 869)

Methodius: Thessalonica, Greece (AD 826–AD 885)

Feast day: February 14

Cyril (also called Constantine) and his brother Methodius were Greeks from Thessalonica. Pope John Paul the Great proclaimed them to be “Apostles to the Slavs” and copatrons of Europe — along with St. Benedict of Nursia — for their missionary work among the Slavic peoples of Eastern Europe.

Methodius chose to embrace a monastic life, while Cyril, adept in languages and with a keen mind for theology, wanted to be a scholar. Cyril corresponded frequently with Jewish and Muslim scholars, trying to bridge the gaps among the three great monotheistic religions (Judaism, Islam, and Christianity).

Cyril’s and Methodius’s work with language and religion became well known; the two were sent to Moravia to unify those people under one language, alphabet, and religion. The Germans had been teaching the Moravians Latin, but Prince Rastislay (ruler of Moravia) sought independence from German influence.

The brothers firmly believed in using the vernacular of the local people, a belief that was in sharp contrast to the customs of the day. In the Western empire, Latin was the standard language of law, academics, and church; in the Eastern empire, it was Greek across the board. The brothers trained men for the priesthood and sent their trainees to Rome to be ordained. The German bishops contested their ordination, complaining that the new priests didn’t speak Latin. The Pope rejected those arguments, allowed the men to be ordained, and gave them permission to use Slavonic in their home parishes as an approved liturgical language.

St. Dionysius the Great

Alexandria, Egypt (AD 190–AD 264)

Feast day: November 17

Dionysius, a disciple of Origen, was born and raised in a pagan family, but as a young man, he became very well read and learned. His studies sparked a love and curiosity for truth and wisdom, which eventually led to his conversion to Christianity. After he was baptized, he used his intellectual abilities to refute heresies and to explain and defend the newfound faith he enjoyed.

He became Bishop and Patriarch of Alexandria and vigorously defended the doctrine of the Trinity. Dionysius also battled the heretical Novatians, who maintained that the lapsi (Christians who had renounced their faith during the Roman persecutions) could never be reconciled back into the Church. He believed the mercy of God extended to the lapsi if they repented, made a good confession, and did proper penance.

St. Gregory of Nazianzus

Arianzus, near Nazianzus, in Cappadocia, Asia Minor (AD 329–AD 390)

Feast day: January 2

Like his friend St. Basil, Gregory was raised in a family that would become quite holy: The son of St. Gregory of Nazianzus the Elder and St. Nonna, he was also a brother to St. Caesar Nazianzen and St. Gorgonia. Gregory’s father was a former pagan who went on to become Bishop of Nazianzus. When Gregory the Elder was 94, he made his son his co-adjutor bishop — the person who automatically ascends to the bishopric at his predecessor’s death, resignation, or retirement.

The younger Gregory was a reluctant cleric at first. He didn’t feel worthy of the priesthood, let alone the possibility of becoming bishop. His father convinced him, however, what a great asset he would be to both the Church and to his father if he were to accept the position. Together they battled the Arians, and the younger Gregory was named bishop in AD 370.

Gregory reluctantly accepted the position of Archbishop of Constantinople in AD 381, in the reign of the Emperor Valens, who was a staunch Arian. Valens was succeeded two years later by Emperor Theodosius, who was a vigorous opponent of Arianism. Gregory became the subject of slander, persecution, and physical abuse for his efforts to reunite former Arians with the Church. He longed for solitude, away from the politics of the imperial city, and resigned his office seven years before he died in his hometown.

St. Gregory of Nyssa

Caesarea in Cappadocia (AD 330–AD 395)

Feast day: March 9

Gregory was the brother of St. Basil and a friend of St. Gregory Nazianzus (see Basil’s and Gregory’s entries earlier in this chapter). A rhetorician by trade, he was so disgusted by his students’ apathy that he left teaching to become a monk and enjoy the quiet of the monastery.

When Basil became Bishop of Caesarea, he persuaded Gregory to take the assignment of Bishop of Nyssa in AD 372. Nyssa was filled with Arians, and Gregory attempted to restore the teachings of the Church. Arian Governor Demosthenes falsely accused Gregory of mismanaging church property and had the bishop imprisoned. Gregory escaped but was deposed, only to be reinstated when Emperor Gratian intervened.

Gregory attended the Second Ecumenical Council of Constantinople I (AD 381), which reaffirmed the condemnation of Arianism from the First Ecumenical Council of Nicea (AD 325). So eloquent was Gregory at this gathering of the bishops that he was called the “Father of the Fathers” for being a pillar of orthodoxy and staunch defender of the faith.

St. Gregory Thaumaturgus

Neocæsarea, Asia Minor (AD 213–AD 270)

Feast day: November 17

Born to wealthy pagans, Gregory and his brother chose to be lawyers, but on their way to the academy, the two met Origen and entered his theology school in Caesarea. (Origen was one of the most influential, prestigious, and premier Greek theologians and philosophers of his day at the turn of the third century. His teachings impacted many generations.) There they converted to Christianity.

Gregory still wanted to be a lawyer, and he returned to Neocæsarea in AD 238. The 17 Christians of his hometown learned of his conversion and elected him their bishop. His preaching was only outdone by his miraculous cures (healing the blind, deaf, lame, and so on), and he was given the name Thaumaturgus, which is Greek for “wonder worker.” When the Decian persecutions arose in AD 250, he urged his people to go into hiding, and he and a deacon fled to the desert for two years. On his return, Gregory had to contend with plague and the barbarian invasion of the Goths. Still, he and his diocese persevered and survived.

St. Ignatius of Antioch

Rome (AD 35–AD 107)

Feast day: October 17

Ignatius was a friend of St. John the Evangelist and the third Bishop of Antioch. Some say Ignatius was the young boy Jesus took into his arms in the Gospel of Mark 9:35, although no evidence exists to substantiate this claim.

Having survived the persecution of the Roman Emperor Domitian, Ignatius was martyred by the Emperor Trajan in AD 107 by being mauled by wild animals. The journey to Rome — and his death — took several months, and Ignatius used the time to write letters that early Christians used as words of encouragement.

In his letter to the Romans, Ignatius wrote:

I am God’s wheat and shall be ground by the teeth of wild animals . . . Let me be food for the wild beasts, for they are my way to God. I am God’s wheat and shall be ground by their teeth so that I may become Christ’s pure bread. Pray to Christ for me that the animals will be the means of making me a sacrificial victim for God.

St. John Chrysostom of Constantinople

Comana, Asia Minor (AD 347–AD 407)

Feast day: September 13

John’s eloquent preaching style earned him the name Chrysostom, which is Greek for “golden mouth.” He was ordained to the minor order of Lector (Reader), which enabled him to read the Sacred Scriptures aloud at Mass. Bishop Meletius saw promise in John and ordained him a deacon in AD 381; Bishop Flavian, who succeeded Bishop Meletius, ordained John a priest in AD 386. John became renowned for the power and instruction in his sermons, and word of his spiritual wisdom got back to the emperor.

Emperor Areadius wanted John to replace Bishop Nectarius of Constantinople when he died in AD 397. John was the presumed replacement for Flavian at Antioch, but the imperial influence was such that even the Patriarch Theophilus of Alexandria consented to John being sent to Constantinople. John was ordained bishop in February of AD 398.

John was a reformer of the human heart, seeking to eliminate scandal by removing temptation altogether, ordering clergy not to have vowed religious virgins living with them as housekeepers. He cut his own living expenses in half and ordered the monks to stay in their monasteries.

Despite his friendships with Pope Innocent I and Emperor Honorius, John’s enemies in Constantinople, Antioch, and Alexandria made life a living hell for him. He was constantly persecuted and subjected to lies, slander, and attempts on his life. He was eventually exiled to Pythius but died on his way there.

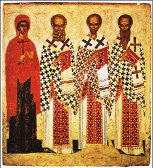

Figure 16-1: An icon of the female martyr St. Paraskeve with SS. Gregory Nazianzus, John Chrysostom, and Basil the Great.

St. John Damascene

Jerusalem (AD 676–AD 749)

Feast day: December 3

John was also known as Chrysorrhoas (golden stream) and is considered the last Church Father, chronologically speaking. After Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor on Christmas Day in the year AD 800 by Pope Leo III, the Middle Ages were fully under way, and the days of the Fathers of the Church, both East and West, were considered a closed chapter.

John’s father, Mansur, was a wealthy financier who was allowed to remain a Christian and keep his wealth, which he used to buy the freedom of Christian slaves.

Mansur hired a monk to tutor John in philosophy and theology — a job the monk did so well that John fell in love with both subjects. Devouring everything he could read, John showed an almost unprecedented intellectual capacity. He applied his learning to defending the faith, especially against the heretical iconoclasts.

The iconoclasts saw images of God, the Virgin Mary, and the saints as idols, and they destroyed whatever they could get their hands on. John Damascene disproved and rebutted their arguments, creating some powerful enemies for himself. Some believe that Germanus, Patriarch of Constantinople, schemed against him and forged a letter implying that John betrayed the caliph (Muslim secular ruler). The caliph then ordered John’s hand chopped off; when the Blessed Virgin Mary miraculously appeared and reattached John’s hand, the caliph’s trust in John was restored.

St. Justin Martyr

Rome (AD 100–AD 164)

Feast day: June 1

Justin was a pagan philosopher who converted to Christianity at the age of 30. At first, he thought the wisdom of the Roman Stoics or the Greek Platonists would satisfy his intellectual hunger. He later realized that there was something beyond human knowledge, a divine wisdom, that could only be obtained by faith. As a Christian, he cherished divine revelation, not as something in competition with human philosophy but as an improvement and perfection of it.

Justin was killed during a trip to Rome. He went to establish a school of Christian philosophy but was confronted by pagan philosopher Crescens, who denounced him to Roman officials as a Christian. When Justin and six of his companions failed to worship the Romans’ pagan deities, they were tried and convicted. Justin was beheaded at the empire’s order. His writings survived, however, and they had a pronounced influence on winning more converts from Roman and Greek paganism over to Christianity.

St. Polycarp of Smyrna

Smyrna (Turkey) (AD 69–AD 155)

Feast day: February 23

Polycarp was a disciple of the Apostle St. John the Evangelist and was a friend of St. Ignatius of Antioch. His letter to the Philippians, one of the few nonbiblical religious documents still intact, shows the existence and usage of New Testament literature during the beginning days of the ancient Christian Church.

The Romans considered the Christians to be atheists because they refused to embrace the polytheist pagan religion of the empire. The hatred for Polycarp was intense, as he was seen as a leader of this countercultural sect. Wanting to feed him to the wild animals and watch him be torn to shreds, the mobs urged the Roman officials to kill Polycarp in a horrible manner. Polycarp’s enemies first attempted to burn him at the stake, but his body miraculously would not ignite. Angered, they then stabbed him to death (his blood put out the fire) and thus gave him a martyr’s death. Polycarp’s writings, verified by Irenaeus, give witness to the direct connection between the Apostles and the continuity of teaching and doctrine.