My Position on Subway Fares

by John Hodgman

Many people have asked me to explain my position on the New York City subway fare increase from $2 to $2.25. I am happy to oblige, and to do so, I present these two true stories that happened on two separate lines of the subway.

The L Train

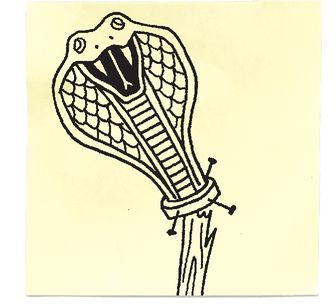

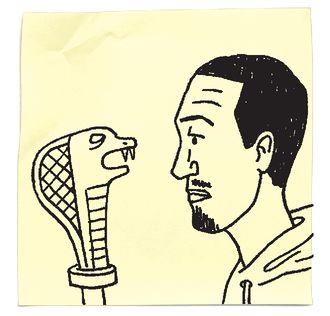

It is not necessary for you to know how I came to own a small green staff with a large green Styrofoam cobra head on top.

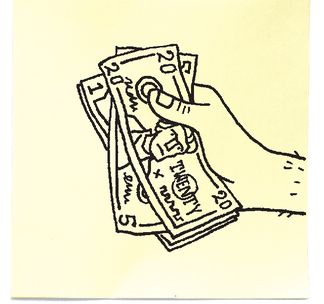

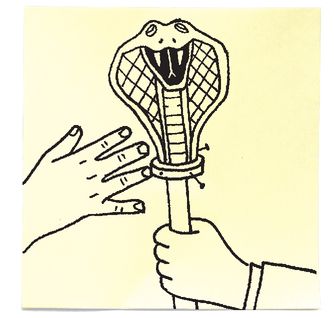

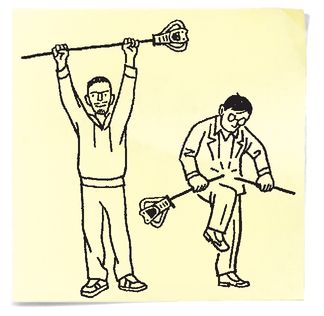

Suffice it to say I was taking the L train last week, holding my cobra staff with the rubycolored plastic gem eyes, which until recently I owned.

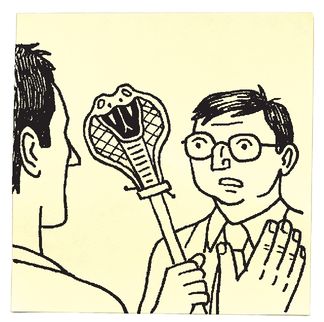

When the train reached Union Square, a gentleman, whose name I would later learn is Marcel, sat down beside me. And I could tell he was checking out my cobra staff.

This came as no surprise to me. In fact, the staff had been getting a lot of attention all day—people would look at it, and then at me, and then at the staff.

I know they were all thinking, “There’s got to be some story here, about why he owns that cobra staff. Is he some kind of wizard?”

The fact is, there is a story, but not very much of one. And so it was then and there that I established my policy on the matter: You do not need to know.

But Marcel was a determined man. “That is really something,” he said in a Haitian accent. “Do you know how much it is worth?”

As it happens, I did know. It was worth exactly zero dollars because I had no use for it, because I am not a wizard. Also, it was a very shoddy cobra staff.

It was just a cut-off piece of broomstick, and if there are grades of broomstick, this was the lowest, most splintery grade. And barely painted green.

The snake head had been nailed on so sloppily that it offended my sense of craftsmanship. No one is making cobra staffs with pride anymore.

But I also knew that it was worth twenty-eight dollars, which was the offensively huge sum that had been paid for it by an actor friend of mine.

OK. Here is why I owned the cobra staff. This actor had bought it for a show he was doing.

I looked at it and said, “That is really something,” and so he gave it to me.

When I found out that it had cost twenty-eight dollars, all novelty value of having a cobra staff evaporated. I was disgusted, and insisted on returning it.

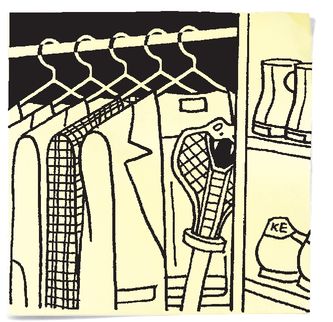

But he refused to take it back. In fact, he seemed relieved to be rid of it. I put it in my closet, and there it stayed, until today.

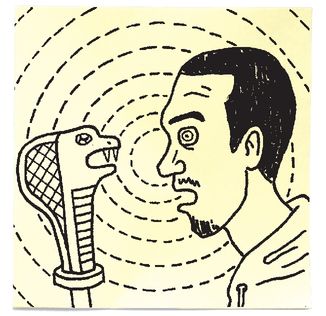

I told Marcel all this because he was still staring at it, as if hypnotized. That is what cobras do, of course: They hypnotize their prey.

“You should have it appraised,” he said. And then he told me about a friend of his who had found a ring on the beach.

The ring was dark and discolored, but when he polished it, it was very beautiful.

And so he took it to be appraised, and it turned out to be worth seven thousand dollars.

I told him that I was fairly sure my snake staff was not worth seven thousand dollars. In fact, my guess is that it could only have depreciated from its top value of twenty-eight dollars.

The once dramatic forked tongue had broken off in my closet, since it was made, I may have mentioned, of shitty Styrofoam.

And in fact I was now taking the train to Williamsburg to return it to the actor who had given it to me in the first place.

But Marcel said, “You don’t know. You don’t know. To me it could be worth five thousand dollars.” Suddenly we were negotiating.

So I said, “Sold.”

And he laughed and said, “No, no thank you, no. That wasn’t the point.” He said, “Things are worth different amounts to different people.”

I knew he was right, because I knew that my cobra staff was worth zero dollars and twenty-eight dollars at the same time.

So I said, “Twenty-five hundred.” But he said, “No, no, thank you.”

And then Marcel said, “Maybe it will be on television. Maybe the actor will appear with it on a television show.”

He was laughing again, but also serious, and even a little scared. He wanted it. The snake eyes had done their work.

And I said, “Believe me, if this cobra staff is ever on television, they will be lining up to pay me five thousand dollars for it. Take it now, for a grand. That’s a steal. It’s a conversation piece.”

Which was true enough at that point. It was worth something now, to be sure, to provoke this rare and strange conversation. It was twenty-eight dollars’ worth of snake staff, at least.

So when we reached Williamsburg, I said, “One hundred cash will take it away.” But Marcel just kept staring, and then said in a kind of dreamy voice:

“My daughter will be very angry if it is on television and I did not buy it.”

At that point, I probably should have just given it to him, but I didn’t. Because I had become greedy, the snake staff became worthless again.

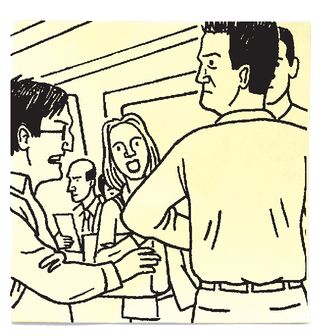

And, sensing that spell was broken, Marcel said, “No, thank you, no.” Then my stop came, and we shook hands, and he told me his name.

We would never see each other again, unless, of course, one of us shows up on TV someday.

Meanwhile, I gave the staff back to the actor, who refused to take it, so we left it there, in Williamsburg, where perhaps it is still, waiting.

The Number 6 Train

When I first moved to New York, a ride on the subway cost $1.25.

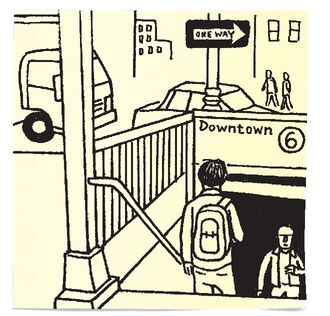

I took the number 6 train to work every morning.

If you know your subway history, you know that when the Second Avenue elevated train was destroyed, in 1942, it left only one subway line on the East Side.

The number 6 commute became a massive, churning, full-body massage in suits.

One morning, I got on the train, and there were no seats. I was twenty-two years old, able-bodied, and college educated.

I knew I deserved a punch in the mouth more than I deserved the offer of a seat from a kindly stranger.

I did what I was supposed to: I didn’t linger in the door wells, always moved to the center of the car, and maneuvered around my fellow citizens as they swayed and lurched.

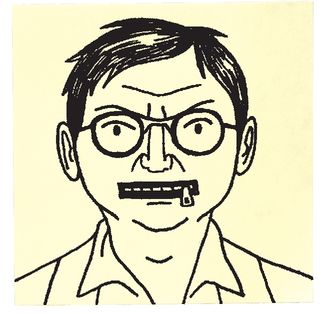

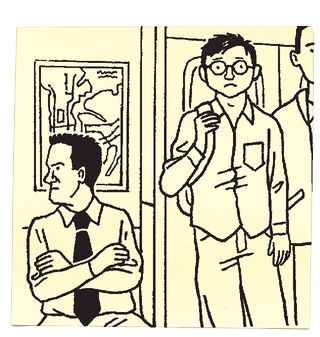

I must have brushed the back of a young man who was standing facing the window, because he turned around and said, “Stop touching my back.”

I said, “Excuse me.” But the young man was not satisfied, now yelling, “Stop touching my back!”

I should point out, I had already stopped touching his back about a thousand years ago, or so it felt now as he glared at me.

And then he hit me. He lowered his hand from the strap and slammed his elbow into my jaw.

Seats opened up then, for sure. A woman screamed and moved away from him and he sat down.

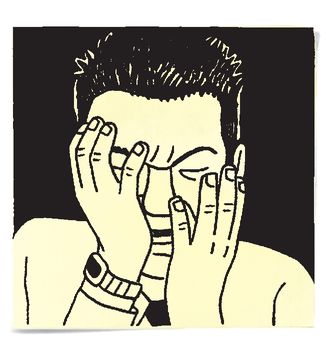

I just stood there, bewildered, shaking, and hurting in the jaw and neck. I didn’t move away; I couldn’t. It was that crowded.

And so I stood there, and he sat there a few feet away, his head now in his hands, and no one knew what to do for a while.

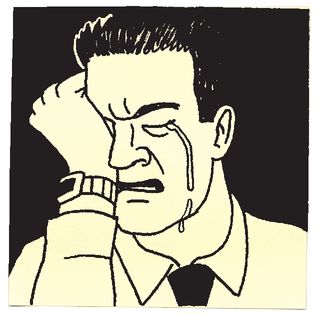

When we reached Fiftieth Street he suddenly looked up and said, “I’m sorry.” He wanted to shake my hand, and I shook his hand. He said, “I’m really sorry. Do you want to sit down?”

And I said, “No. I am fine. We all have bad mornings.”

We rode together in silence for a while more, and by the time we reached Times Square he was crying.

In 1972 they started building a new subway line under Second Avenue. It was an enormous project, and they kept running out of money, until they finally just stopped.

There are still parts of the abandoned line down there, ghosts of tunnel and track. And every year someone in city government would say, “Let’s get that Second Avenue line going again.”

And indeed, they are once again digging on Second Avenue as I write this.

I am not so sure, though, that this is a good idea. Arguably if the train had been less crowded, I would not have been hit in the jaw.

On the other hand, without the human press of the city around us we would have gone to separate cars, never being forced to share that space, never getting to feel that blessing of apology and forgiveness.

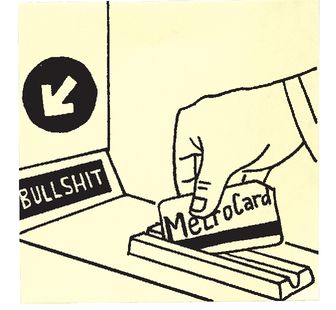

In retrospect, I would say that was certainly $2 worth of subway ride. But $2.25? That, my friends—that is bullshit.