The Four-Minute Drug

by Starlee Kine

Some parents pass on cooking recipes to their children. Others teach them how to Frenchbraid or sew on a button or crush the neighbor kid in soccer. In my family, my sisters and I were taught how to regret.

It was a trait my mom had learned from my grandmother, who had learned it from her own mom, and back and back it went.

For all I know, it started when my first ancestor lit a fire and then spent the rest of his life worrying about it going out.

As a result, I’ve always had a hard time with the concept of living in the moment. What, exactly, makes the moment so special?

There’s a whiff of high school popular kid about it—loved by all for no real good reason.

In The Silence of the Lambs, did Buffalo Bill shout “Live in the moment” to the girl he stuck in that hole?

No; he said, “It puts the lotion on its skin or else it gets the hose again.”

Even the most die-hard optimist has to agree that that was much more sensible advice considering the situation at hand.

The closest I ever came to living in the moment was when I was also living in Chicago.

Occasionally I would hang out with my friend Dave. He was the hypercreative, underachieving little brother of a successful fashion designer.

He was pretty paranoid and loved conspiracy theories. One night when we were out at a bar, he pointed to a poster of the moon landing and grunted.

“Can you believe they’re still trying to sell us on that one?” he said.

He was so skinny that when it got hot he would wear a pillowcase with holes cut out for his arms and head and nothing else.

He lived in a loft with a million other guys and one summer they all pitched in to buy a wobbly Ping-Pong table that was on sale.

Dave turned out to be a sort of Ping-Pong savant, and he spent the next three months in his pillowcase playing nonstop with whoever was around.

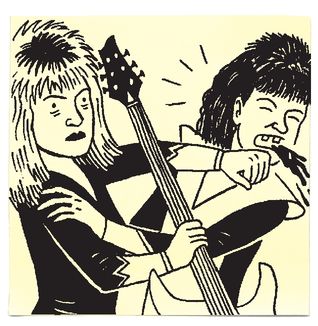

Before I met Dave, he was a determined jazz fusionist. He aspired to be the next Jaco Pastorius, a legendary bassist who wore headbands like a folk singer but died young like a rock star.

Dave practiced so intensely that he injured his hand while playing his bass and had to stop playing.

Depression hit.

He found a job suited to his mood at a local Laundromat, where with each towel he folded he could pretend it was the metaphorical towel that he was throwing in.

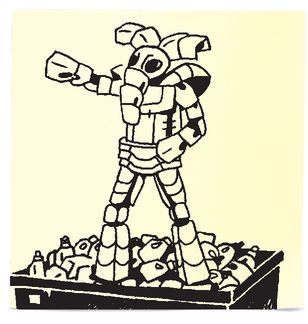

One fateful night, when he was taking out the trash, he looked at the Dumpster brimming with empty detergent bottles and instead of seeing a pile of trash, he saw his future.

He imagined a scenario in which he would gather up the bottles and transform them into life-size robot costumes. And that’s exactly what he did.

Dave’s robot costumes were definitely crazy, but somehow not as crazy as you’d imagine.

They were like suits of armor, complete with helmets and mitten gauntlets and breastplates.

Only instead of metal armor there was plastic and instead of a family crest there were the words Tide and Downy.

In order to enhance the effect, Dave learned how to walk on stilts and soon he was showing up everywhere like that, to readings and rock shows and dinner parties.

Dave’s driver’s license had been revoked a few years before because he’d had an illegal ice cream cone sign on top of his car or something, so you had to go to his house if you wanted to hang out.

His building had the Odwalla juice warehouse on its ground floor and the guys always had crates of remainder juice in their fridge, even when they were at their most broke.

After investing in the Ping-Pong table, none of them could afford to eat for two weeks and they survived on nothing but fancy hybrid beverages.

Which might explain why they were all so good at Ping-Pong in the first place.

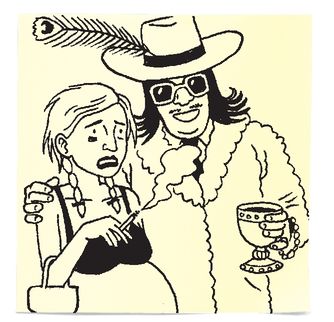

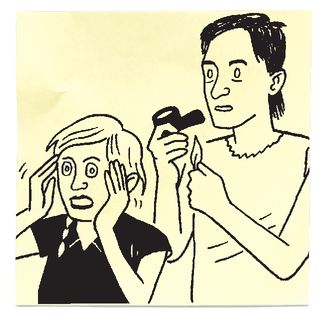

One night I showed up and Dave was looking more excited than usual. “There’s something I want you to try,” he said.

He led me into the living room, which was really just some old theater seats, a piece of wood on cinder blocks for the computer, and a filing cabinet.

On top of the filing cabinet was a stack of three carefully folded knit afghans, which I noticed because they were the one small, dear attempt at domesticity in the entire place.

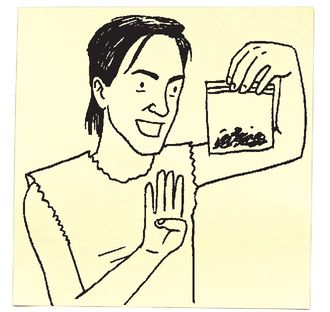

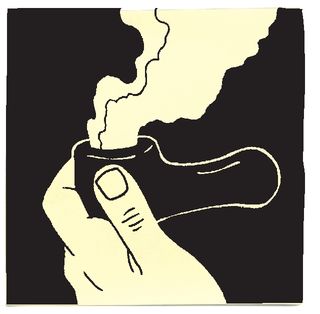

Dave went to the desk, withdrew a Ziploc bag, and held it out to me.

“It’s a four-minute organic drug that I ordered off the Internet,” he said. “It lasts exactly four minutes.”

“Then you go back to just how you were before. There aren’t any physical side effects or anything. And it’ll change your life.”

“In four minutes?” I asked.

“It’s a very intense four minutes.”

“But what can possibly even happen in that time?”

Just then Dave’s roommate, Robroy (real name, one word) popped his head in. “Are you guys talking about the four-minute drug? It’s great; you’re going to love it.”

He told me that when he took it, he was whisked to a bright green field. As Robroy the adult hovered above, Robroy the boy enjoyed a picnic lunch on the ground below with their mom.

They spread soft cheese on slices of bread and were about to start layering on the prosciutto when Robroy was whisked back to the loft.

He said it was the most peaceful four minutes of his life.

Dave nodded enthusiastically. “Totally! Totally!” he kept saying, even though his own experience had been nothing like that.

When he took the drug, he simply entered the wall next to his bed and stayed there until the four minutes were up.

Then he repacked his bowl and tried to enter the wall again, but much to his frustration he kept getting whisked away to other, more exotic hallucinations.

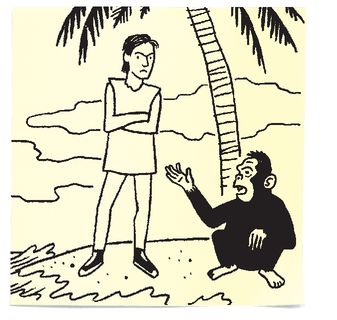

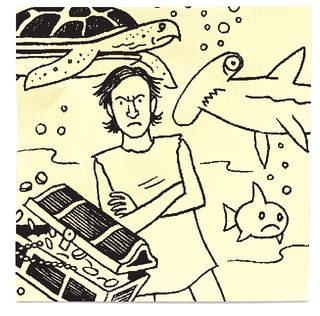

Once, he found himself on a deserted island seeking advice from a chimp.

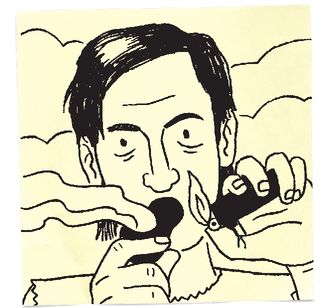

Another time he was underwater and had gills.

Dave wasn’t interested in any of that. He just T wanted back into that wall.

That day, he packed and repacked his bowl eight separate times, but thirty-two minutes later he was right back where he had started.

Just your average robot-costumer conspiracy theorist who had to settle for being adjacent to walls like everybody else.

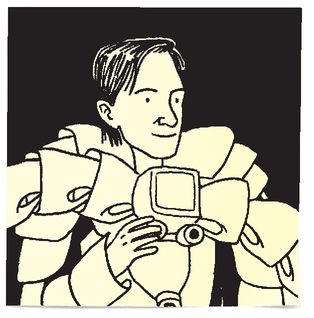

Now, in the living room, Dave offered his pipe to me.

I took it right away, not because I was so curious to try it but because I was in a hurry to get it over with.

I have no problem with most of the aspects of drug taking.

The health risks and the economic ruin.

The lying and the stealing.

The nodding off in public.

The breaking up of the band.

The dipping of a track-marked toe into the disease-ridden waters of prostitution. That all seems fine.

It’s the actual experience that I could do without. Which is why taking this drug seemed, to me, like a win-win situation. I’d only have to “experience” it for four minutes and I’d still get credit.

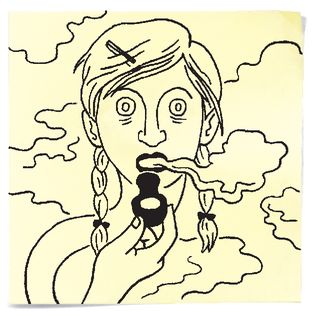

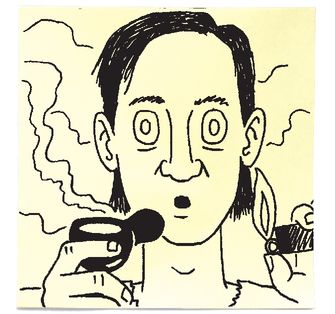

The second I inhaled, something told me it was working. Perhaps it was because I could no longer sense who I was or what life had been like at any point before.

Or maybe the tip-off was that the computer’s screen saver had transformed into an evil, mocking face.

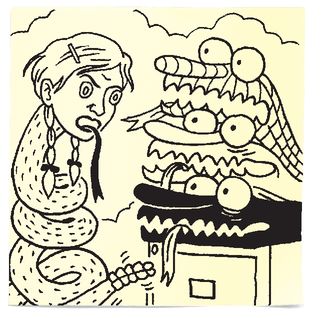

The afghans on top of the filing cabinet were now monsters and the faded paisley rug on the floor had come to life and promptly begun to eat Dave.

Dave later told me that I kept repeating, “Oh this isn’t good; this is not good.”

He said at one point I turned to the afghans and hissed, “So we meet at last!”

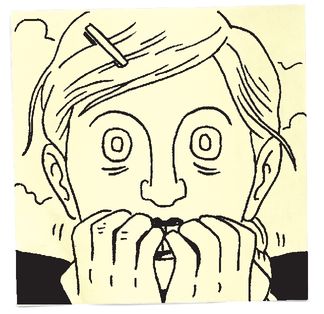

He hadn’t anticipated this reaction at all and was naturally worried. And so he did the only thing he could think of to help. He fired up another bowl.

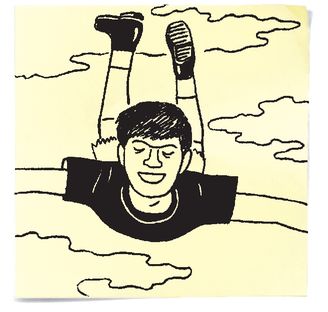

“I’m coming in after you,” I heard him say, but it was so faint, so far away.

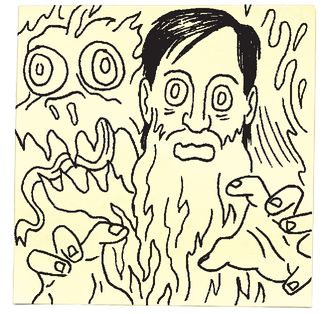

Next thing I knew Dave was diving into the rug as though it were the sea. He disappeared for a second, and then popped his head back out, gasping for air.

I reached out my hand and he tried to make his way toward me, but the waves were just too choppy.

Then he grew a beard, the afghans reared up for the kill, I saw sharp teeth, and the screen saver laughed and laughed.

I was sure it was all over for us both.

Then just as quickly as it had started, it stopped. My identity came rushing back. I could again conceptualize space and time.

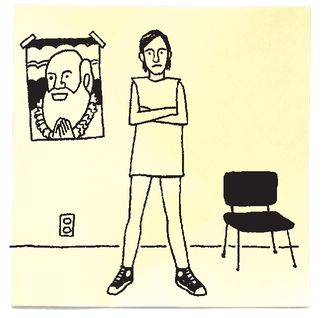

If Robroy had chosen to take the four-minute drug right then, this is what he would have seen as he hovered above:

Me curled up on my chair, trying to make sense of the thrashing, flailing, dog-paddling Dave on the rug below.

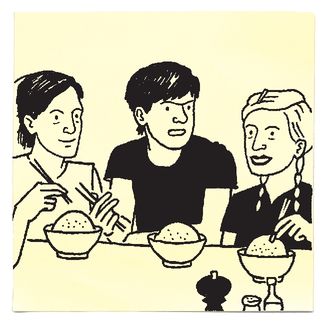

“That was the worst four minutes of my life,” I told Dave once he’d recovered and dusted the lint from his pillowcase.

We went into the kitchen, where Robroy handed me a bowl of white rice and then the two of them asked me question after question about what it was like to not enjoy drugs.

Until meeting me, it had never occurred to them that such a thing was possible.

I answered as best I could, using props when words wouldn’t suffice: the saltshaker as me, the pepper mill as Dave, an empty Odwalla juice bottle as the screen-saver demon.

There was a definite vibe of sweaty accomplishment in the air; I’d lived through living in the moment . . . and survived. Now all I had to do was make sure it didn’t happen again.