Alaska Death Trip

by Arthur Bradford

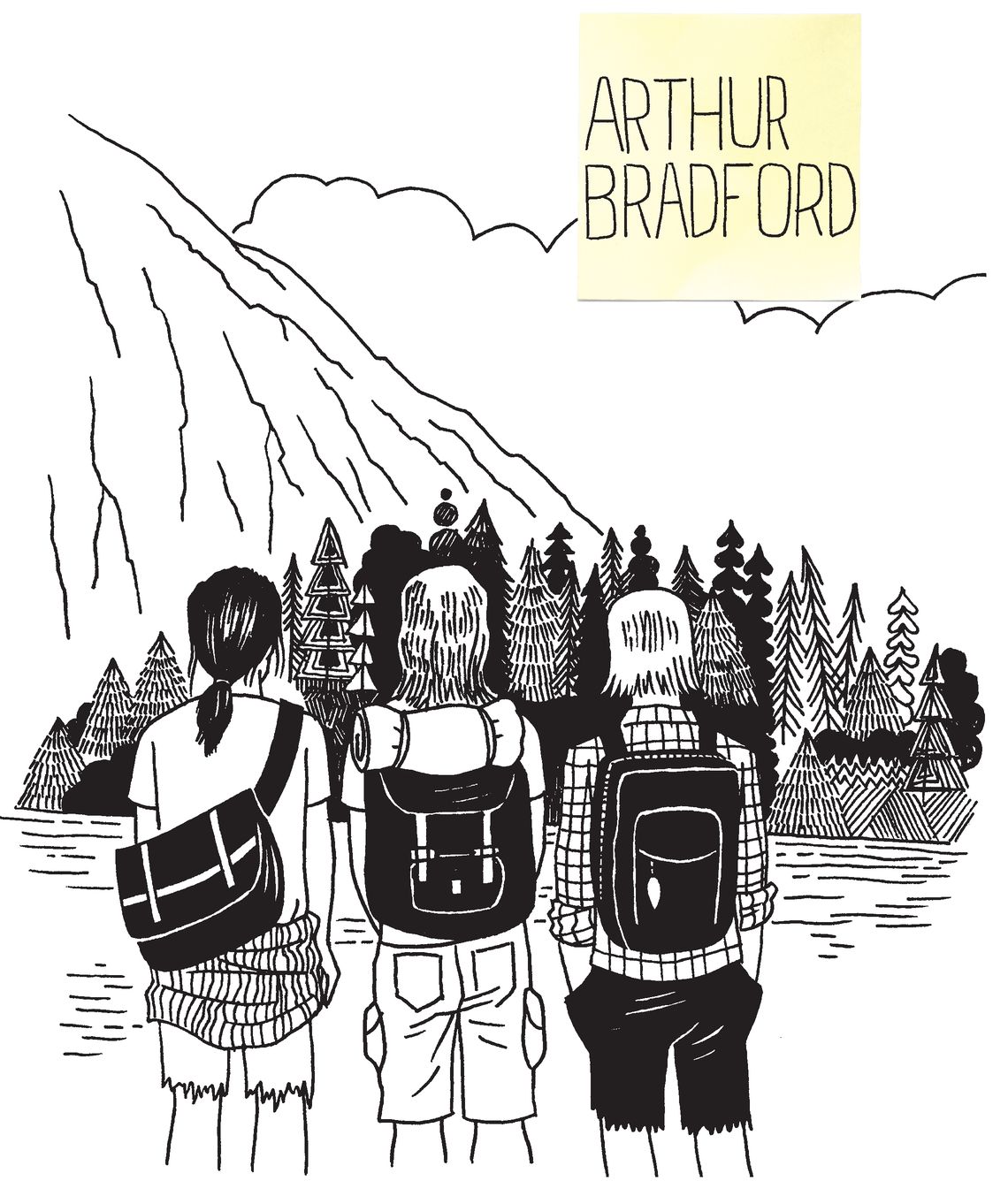

Upon graduation from high school I teamed up with two friends, Matt and Fred, and we decided we would make our fortunes working in the fishcanning factories of Alaska.

Our plan, such as it was, consisted of driving from our homes in New England across Canada, and then into the wild Alaskan frontier.

None of us owned a reliable vehicle, so I convinced my grandmother to lend us her old Jeep Wagoneer.

We all met up at Grandma’s house one night and after dinner we decided we should hit the road then and there.

It was late and my grandmother urged us to spend the night and leave in the morning, but we were having none of that. We were too excited.

The open road awaited us! Those fish canneries were calling our names!

We left around midnight and soon ran out of gas.

All the gas stations were closed at that hour so we spent that first night in the Jeep only a few hours from where we had started.

In the morning we filled our tank and crossed the border into Canada. That setback with the gas gave us an idea: Why stop moving?

We could just rotate drivers and sleep in the Jeep all the way to Alaska. We’d make great time!

We sped past the Great Lakes, stopping only for short meals and bathroom breaks.

A driving hierarchy was established. Matt was the best driver, so he drove for the longest stretch, usually well into the night.

He’d wake me up around dawn and I’d sleepily take the wheel. I remember waking at dawn at the foot of the great Canadian Rocky Mountains.

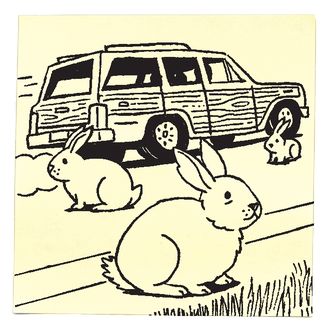

Matt handed me the wheel and before he went to sleep in the backseat he said, “Look out for the rabbits.” I was confused at first, but then as I drove, I saw what he meant.

There were rabbits all over the road, hundreds of them. Something about the heat of the asphalt had drawn them there.

I tried to drive around them or slow to a crawl, but they just darted under the tires.

I kept hearing these awful little thuds. It was ridiculous, like they were bent on suicide.

Finally I stopped driving and yelled at them, “Get off the road! Fucking rabbits!” This didn’t help.

Fred was the worst driver of our group. Matt and I would try to sleep while he careened down the mountain roads, but we kept banging our heads on the sides of the Jeep or falling off the seats.

Fred loved to accelerate and then hit the brakes once he realized things were going too fast. It was a poor driving technique. Even so, we were making great time.

We soon reached the Yukon, home of the mythical midnight sun. It never gets dark there!

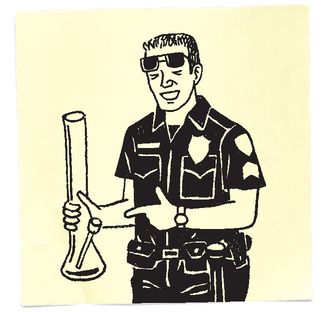

The border crossing back into the U.S. was just a little set of trailers and a makeshift toll bar across the road.

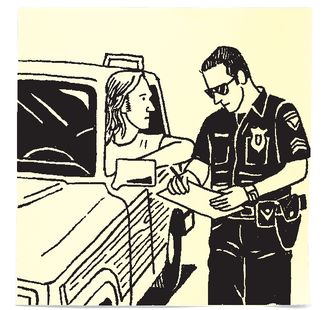

The border patrol agent asked us if we had any guns or weapons to declare and we replied that we did not.

I remember wondering if we should have weapons to declare. This was the frontier, after all.

Then the border agent asked, “Do you have any drugs or drug paraphernalia to declare?” “No,” I said, “we don’t.”

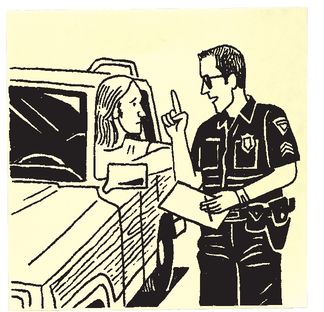

I suppose I wasn’t very convincing on this point. The agent said, “Please step out of your vehicle.”

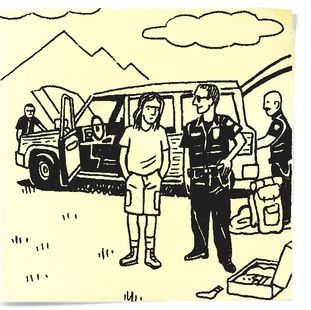

They searched the Jeep and found a two-footlong water pipe, also known as a bong, and a bag of weed.

I thought we would be arrested on the spot, but instead, the penalty for our crime was the seizure of our vehicle.

The nearest town was a hundred miles away, a little Alaskan village called Tok. The irony of that name was not lost on us, by the way.

The only way to get a ride out of there was to split up. Alaska is a terrible place to hitchhike, we soon learned, because there’s no such thing as a short ride.

If you pick someone up, that person is with you for hours—days, even.

After hours of rejection, I finally caught a lift to Tok with a Canadian fur trapper named Bill.

Matt and Fred arrived a little later in the back of a border agent’s truck, sandwiched between two big huskies.

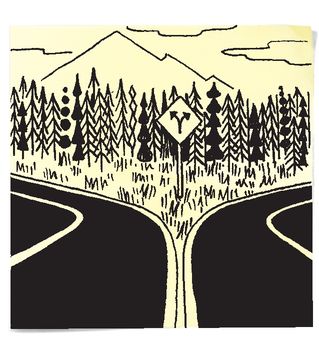

Tok stood at the divergence of two roads along the Alaska Highway. One led to Anchorage, and the other to Fairbanks. Each city was about ten hours away.

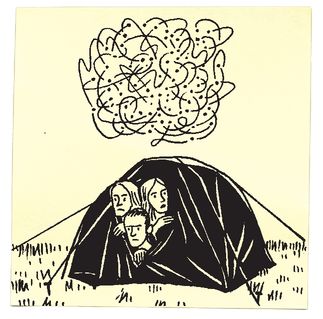

We were stuck there for nearly a week and it rained the entire time.

A local gas station had built a statue of the world’s largest mosquito.

This might have been amusing to us if we hadn’t been sleeping in tents each night and getting attacked by the real things.

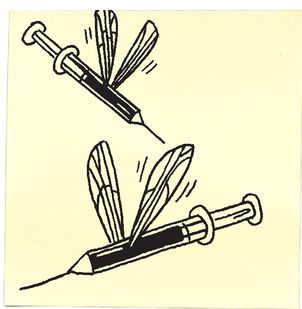

The mosquitoes up there are enormous, like flying syringes.

After the Jeep was seized I placed a phone call to my grandmother. I told her the good news was that we had made it to Alaska.

“The bad news,” I said, “is that when we reached the border they found some marijuana and a pipe in the vehicle.”

There was a confused silence on the other end of the line. “Now how did that get there?” she asked.

My poor grandmother was honestly wondering if perhaps one of her acquaintances had dropped the drugs in her Jeep on some earlier occasion.

I set her straight, however.

We pinned our hopes of escape on a legal loophole: The Jeep belonged to my grandmother, and since she’d had no knowledge of our drug smuggling, she might be allowed to have it back.

My grandmother signed some papers and faxed them to a lawyer in Anchorage who, after nearly a week of haggling, somehow got this logic to stick.

Much of our time in Tok had been spent waiting around in the town’s one bar.

When we learned that the Jeep had been released we offered one of our drinking companions twenty bucks and a radio cassette player to drive us back to the border so we could retrieve it.

This man, who was known as Eric the Eskimo, traded the radio to the bartender for eight beers, so we didn’t end up leaving until 2:00 a.m.

The Jeep had been sitting in a dirt parking lot at the border for more than a week.

When we arrived and opened the door an amazing puke-inducing odor of spoiled ham, old socks, and rotten milk assaulted us.

Matt and I opted to ride back to Tok with Eric the Eskimo, while Fred braved the stench and drove the Jeep.

The rain had ceased and a beautiful misty morning emerged as we got under way. We were finally back on the road and I recall thinking that now, at last, our luck might change.

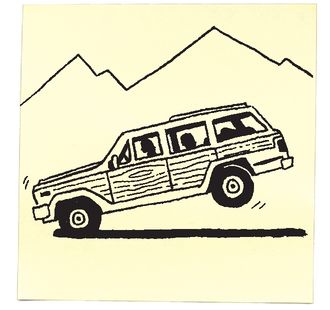

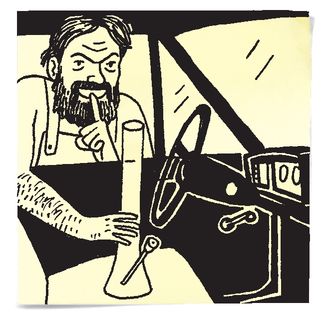

Speeding along in the Jeep ahead of us, Fred reached down to the floor to find a new cassette for the tape player.

The wheels of the Jeep drifted into the soft sand shoulder.

Fred popped his head up and slammed his foot on the brake.

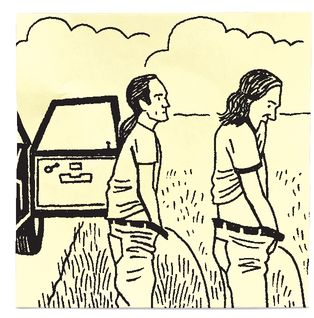

The Jeep swerved and then began an incredible series of cartwheels, flipping end over end across the barren highway.

When it finally came to a stop the Jeep lay on its side, tires spinning, smoke rising from the crumpled hood.

“Oh Jesus,” said Eric. I just sat there repeating, “No, no, no . . .” I thought Fred might be dead.

But then Fred climbed up out of the Jeep’s window, rubbing his head and cursing repeatedly. “Shit. Fuck. Shit. Fuck.” He kept saying that over and over.

He was fine, though, except for a bump on the back of his head. Of all the dumb shit we had done on that trip, at least we’d made a habit of wearing seat belts.

Eric said, “You boys are lucky to be alive. All of you.”

But we didn’t feel lucky at all. We spent an hour and a half cleaning up all the crap on the fi highway. h

Bits of glass, ripped up tires, clothing, broken fishing rods—it was scattered everywhere for hundreds of feet.

There were big divots in the road at each spot where the Jeep had come down. I surveyed the scene and stood amazed at the degree of destruction we had wrought upon this land.

The whole time we were out there cleaning up E that mess only one vehicle passed by, a long h haul trucker who radioed the state police.

Eventually a big tow truck came along and hauled the wrecked Jeep’s carcass away. “There it goes,” I thought to myself.

We all got into Eric’s car and drove back to Tok’s only bar in silence.

It was barely 8:00 a.m. when we arrived, but there were several patrons already drinking s and we joined them.

We never did make it to the fish canneries that summer. We painted houses in Anchorage instead, and as soon as we’d amassed enough cash to fly home, that’s what we did.

I think that was the time I learned about limitations, if this makes sense—that there are indeed consequences for our actions.

It seems like an obvious lesson, but I’m pretty certain I didn’t know it at the time. And it wasn’t a bad way to learn it.

Every so often I think it’s OK, even good, to crash and burn, especially when you are young and might gain something from it.

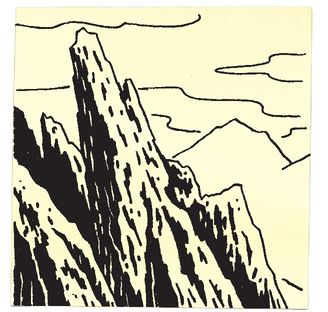

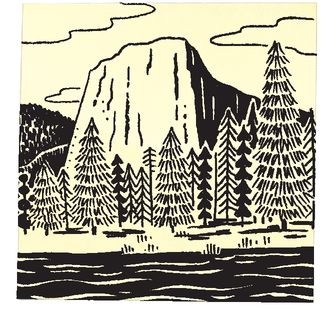

Eight years later, my friend Matt, the good driver, died in a spectacular rock climbing accident on the great wall of El Capitan, in Yosemite.

He’d become a world-class climber and I suppose the whole idea of limitations and consequences never really settled in his mind.

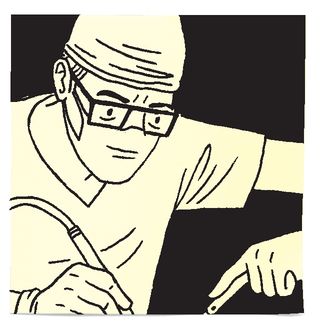

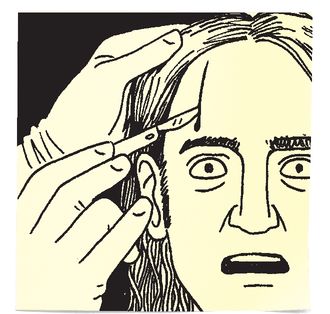

Interestingly, Fred, the poor driver, is now a brain surgeon—a really good one, apparently.

He performs delicate lifesaving operations at one of the most prestigious hospitals in the world.

I’m not sure I’d let him at the inside of my brain, though, to be honest.