Notes on an Exorcism

by Andrew Solomon

I’m not depressed now, but I lived with blinding depression for a long time.

Everything seemed hopeless and even getting out of bed was painful.

When I got better, I started researching various approaches to depression—treatments ranging from experimental brain surgery to hypnosis.

I wanted to explore the idea that there wasn’t just one Western, modern, middle-class way of dealing with depressed people.

I wanted to show that it’s a constant across class, culture, and history.

If you have brain cancer and decide that standing on your head and gargling for a half hour every day makes you feel better, it might make you feel better.

But you will likely still die from brain cancer.

But if you suffer from depression and standing on your head and gargling for a half hour makes you feel better, then you are actually cured.

Because depression is an illness of how you feel.

This principle led me to search for cures of every kind in every place.

I visited my close friend David Hecht, then living in Senegal, who told me about the ndeup, a treatment for depression used by the Lebou people of West Africa.

David’s then girlfriend, now ex-wife, Helene, had a cousin whose mother was a friend of someone who went to school with the daughter of a woman named Madame Diouf.

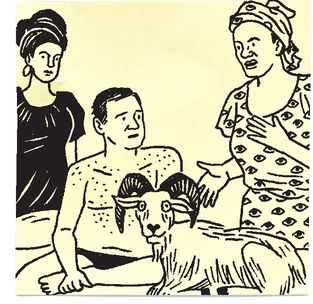

Madame Diouf lived two hours outside of Dakar in a town called Rufisque, and she practiced the ndeup. We decided to drop in.

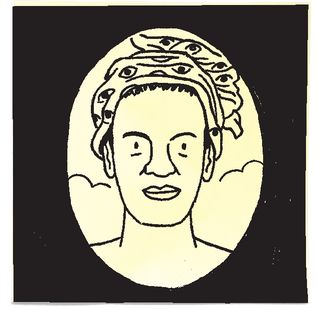

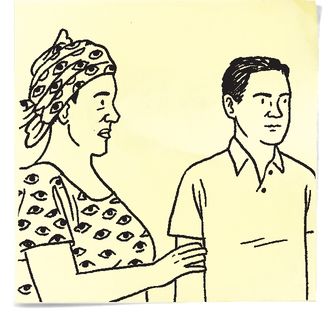

She was an extraordinary old, large woman, wrapped in miles and miles of African fabric printed with images of eyes. I interviewed her about the ndeup.

Then I asked whether I could observe an ndeup, and she said that while she’d never had a foreigner, or toubab, do so before, she would allow me to, because I was a friend of Helene’s.

I asked her when she thought she would next do one, and she said it would be sometime within six months. Since I didn’t have six months to wait, I thanked her and turned to go.

It was at that moment that she said, “I hope you don’t mind me saying this, but you don’t look that great yourself.”

I looked back at her doubtfully.

“I’ve certainly never done this for a toubab before,” said Madame Diouf, “but I could do a ndeup for you.”

“Well, yes,” I said. “Sure,” I said. “Yes, absolutely,” I said. “Let’s do that. I’ll have a ndeup.”

She gave me some fairly basic instructions and told me to come back in two days for the ceremony.

In the car, on the way back to Dakar, my translator, the aforementioned then girlfriend, now ex-wife of my friend, turned to me.

“Are you completely crazy? Do you have any idea what you’re getting yourself into?”

“Well,” I stammered, “being completely crazy is the whole idea; it’s what got me here in the first place.”

“I’ll help you if you want,” Helene said exasperatedly. “But you are totally crazy.”

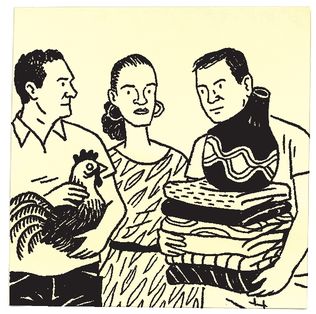

Madame Diouf had given us a shopping list of S items to buy for the ndeup:

even yards of fabric.

A calabash.

Seven kilos of millet. F

Five kilos of sugar.

One kilo of cola beans.

Two cockerels. A

And a ram.

Helene, David, and I went to market with a few other friends and bought all of the items, save one. “What about the ram?” I asked.

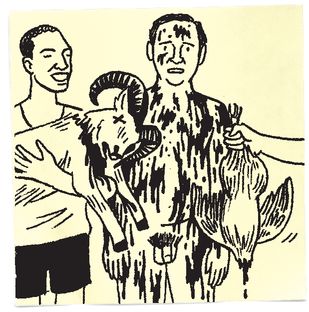

Sure enough, on the day of ndeup, as we drove to see Madame Diouf, we saw a shepherd by the side of the road. We pulled over and bought a ram for about seven dollars.

We struggled a bit to get the animal into the trunk of the taxi, but we did it. The driver didn’t seem to mind that the ram kept relieving himself in the back of his car.

When we pulled into Rufisque around 8:00 a.m., I was feeling nervous.

Though I knew the rough idea, what actually happens in any ndeup varies enormously from person to person and depends on unpredictable messages from above.

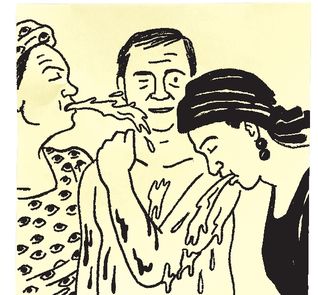

To begin, I changed out of my jeans and T-shirt and put on a loincloth, and Madame Diouf and her attendants rubbed my chest and arms with the millet.

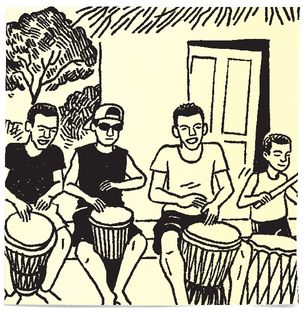

“We should really have music for this,” said one of the attendants, disappearing into her home.

“Oh great!” I thought, expecting atmospheric drumming.

She returned, proudly holding her most prized possession, a battery-operated tape player, blaring music from the only tape she had, which was the soundtrack to Chariots of Fire.

I was given an assortment of sacred objects, which I held in my hands and feet and systematically dropped while Madame Diouf interpreted how each fell.

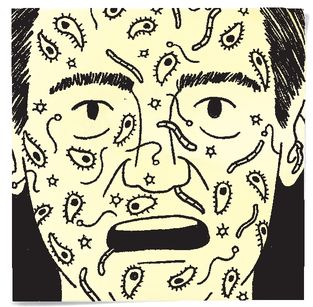

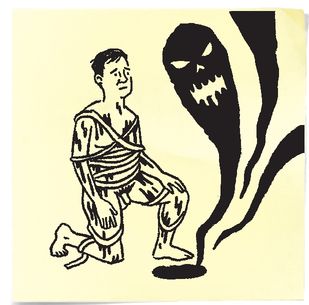

In Senegalese tradition, spirits are all over you—rather like microbes in the Western system—some good, some bad, some neutral.

Madame Diouf determined that I was haunted by jealous spirits who envied my real-life sexual partners, and that for my depression to be cured, these spirits would have to be mollified.

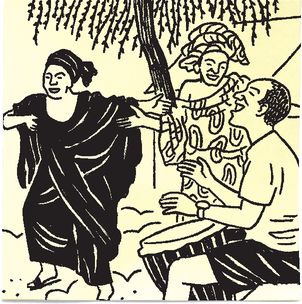

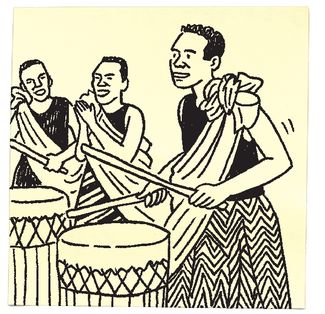

At that point the drumming began—wild, ecstatic drumming of the kind I’d been imagining all along.

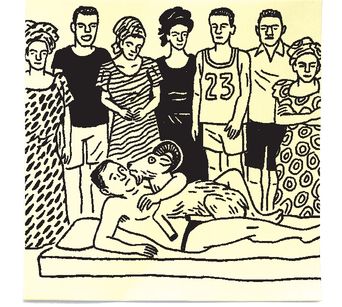

I was led to the village’s central square, where there was a small makeshift wedding bed that I got into with the ram.

I was told it would be very bad luck if the ram escaped, so I held on to him as tightly as I could, an arrangement that was clearly not making him happy.

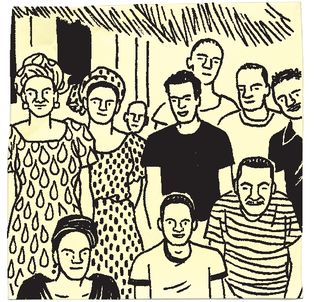

The entire village had taken the day off from their work in the fields.

They danced around us in concentric circles, chanting loudly and throwing blankets and sheets of cloth over us.

We were gradually buried, and it was unbelievably hot and stifling under the heavy fabric, and the ram, who was having a very bad day, urinated all over my leg.

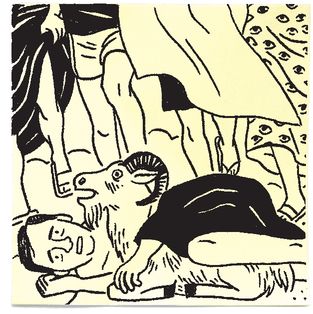

I couldn’t see anything, but the sound of the drums and stamping feet grew more ecstatic and I was just about to pass out when suddenly all of the cloth was pulled off.

I was yanked to my feet and the loincloth was T ripped from me.

The poor old ram’s throat was slit, as were the throats of the two cockerels, and I was covered in their fresh blood.

So there I was, naked and totally covered in blood, and they said, “OK, that’s the end of this part of it.” Then we took a lunch break.

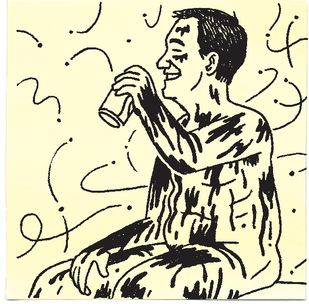

“Would you like a Coke?” asked one of Madame Diouf’s attendants. I don’t normally drink Coke, but at that moment it seemed like a really good idea.

I sat down, still naked, still covered in blood, surrounded by a swarm of interested flies, happily drinking a soda.

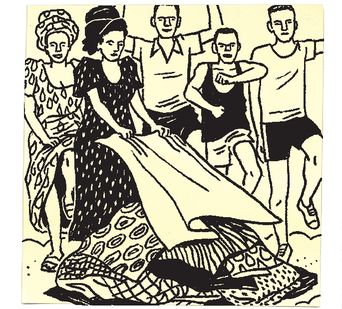

After I finished, the ram was hung from a nearby tree and butchered while a man used a long knife to dig several holes in the ground.

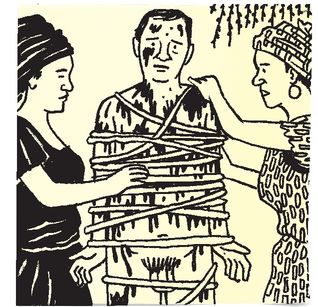

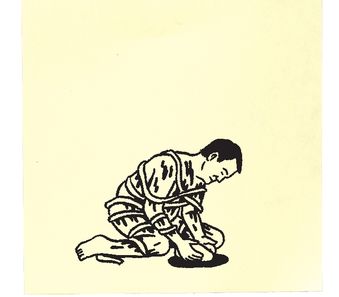

I was made to stand very straight with my hands by my sides and was then tied up with the ram’s intestines.

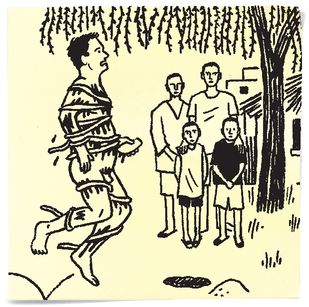

Little bits of the ram’s body were given to me and I shuffled around (which is really hard to do when you are tied up with intestines) and put the pieces into the holes.

All the while I had to say, “Spirits, leave me alone to complete the business of my life; know that I will never forget you.”

Which struck me as a strangely touching and kind thing to say to the spirits I was exorcising.

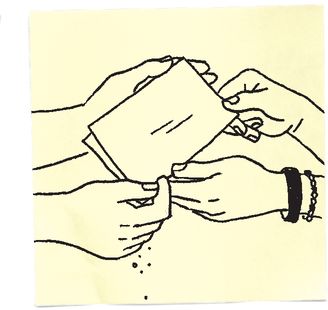

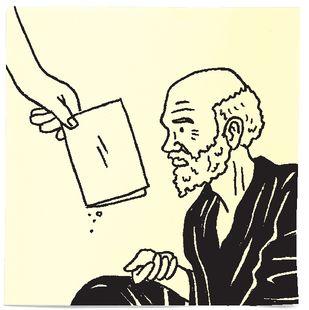

I was given a folded piece of paper in which all of the millet from the morning had been gathered.

I was instructed to sleep with it under my pillow and then in the morning give it to a beggar with good hearing and no deformities. Then all my troubles would end.

Then the women of the village filled their mouths with water and spit it out all over me, rinsing off the blood, much like a surround shower.

After I was clean, I changed back into my clothes and everyone danced and we barbecued the ram for dinner.

And I felt so up! Something in the day had made me feel so exhilarated, and it wasn’t only the prospect of telling the story.

Five years later I was back in Africa and I had a conversation with a man in Rwanda about my ndeup experience.

“Oh, that’s West Africa; this is East Africa,” he said. “There are some similarities in our rituals, but things are quite different here.”

“You know, we had a lot of trouble with Western mental-health workers who came to Rwanda after the genocide.”

“What was the problem?” I asked.

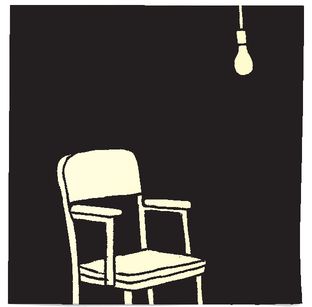

“OK, their practice didn’t involve being outside in the sun, which, as you experienced, is where you begin to feel better.”

“There was no music or drumming to get your blood flowing.”

“There was no sense of the entire community coming together to lift your spirits and bring you back to joy, as there was in your ndeup.”

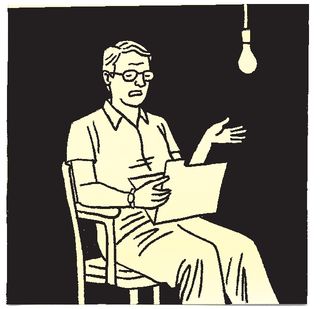

“Instead they took people, one at a time, into these dingy little rooms and had them sit there for an hour and talk about bad things that had happened to them.”

“Of course, it made the depressed people feel worse.”

“We had to ask these health workers to leave the country.”