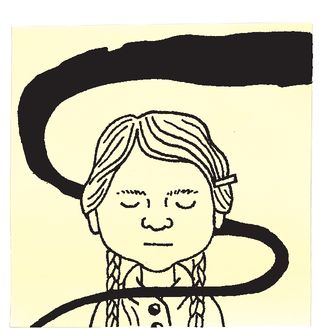

The First Time I Almost Died

by Hannah Tinti

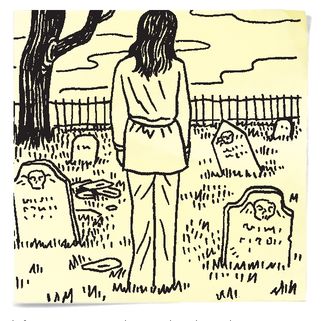

When I was five years old, I went to a kindergarten that was in the basement of a church. For recess, we would play in the graveyard.

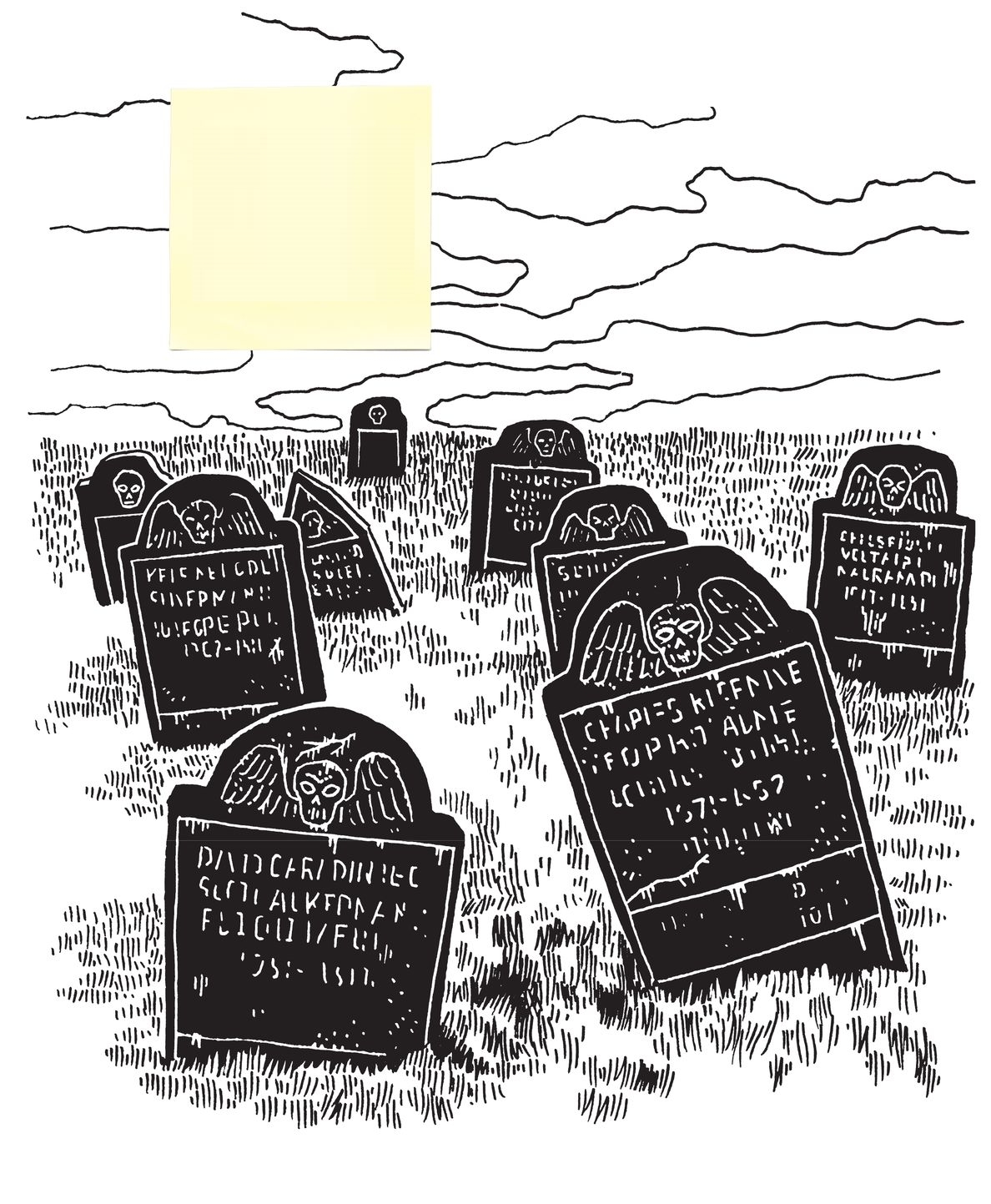

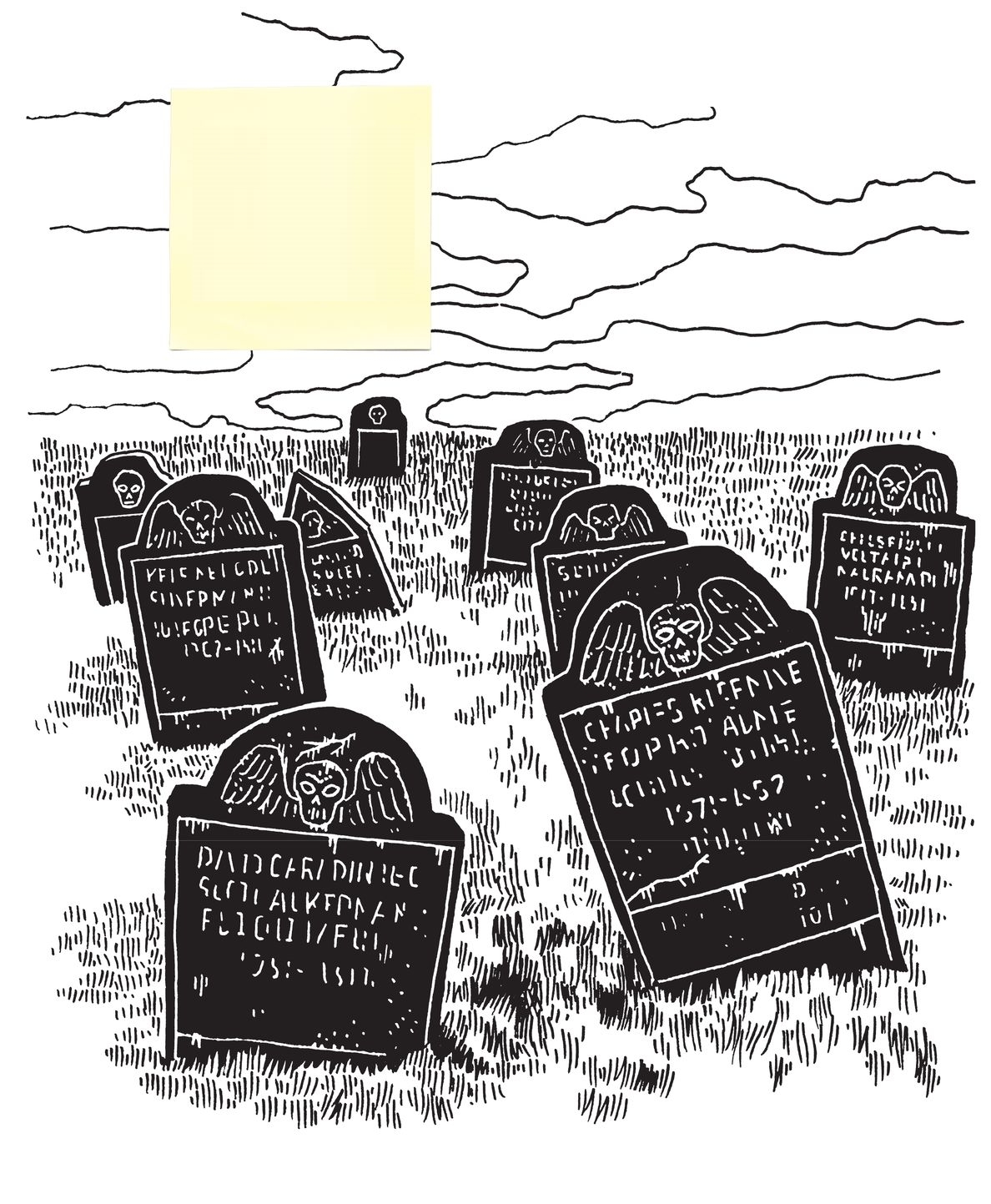

It was an old graveyard, with stones from the 1600s and 1700s. Some people said it was haunted.

But I’d never seen any ghosts there.

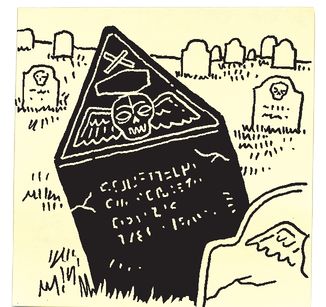

The stones were black slate or sandstone or granite. They tipped left and right, and some were broken.

They had strange faces on them, and trees and angel wings. I thought they were beautiful.

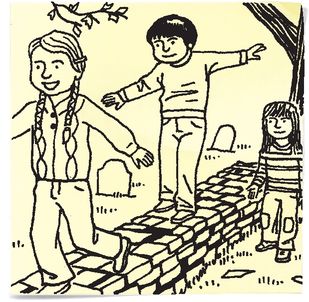

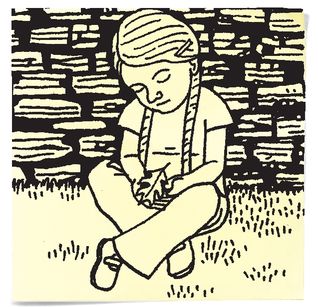

My friends and I played house behind a stone wall that marked off a family plot.

I was wearing a thick Irish sweater, and I took it off and hung it on one of the graves, as if it was a coat rack.

We shared a dinner of twigs and leaves.

Then we all went to sleep. We pretended the headstones were the headboards of our beds. We stretched in front of them on the grass.

I thought about the real family buried beneath us. I wondered how far down their bodies were.

One of the teachers rang the bell to go back inside.

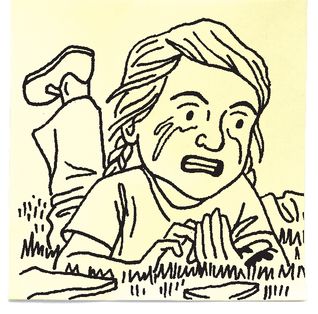

I hurried to get my sweater, and on my way something reached out and tripped me.

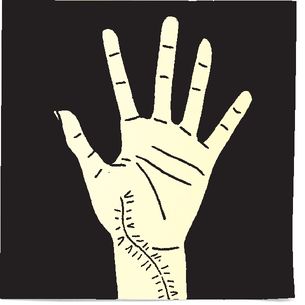

I collapsed onto one of the broken gravestones, and a jagged piece of slate went through my left wrist.

I didn’ t understand what had happened. I lifted my head from the ground. And then I saw blood. Lots of it.

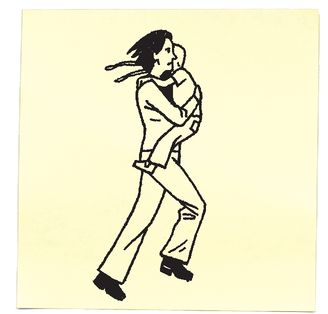

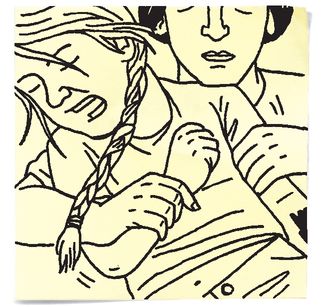

One of the teachers grabbed me and started to run.

She ran all over the school, screaming, with me hanging over her shoulder.

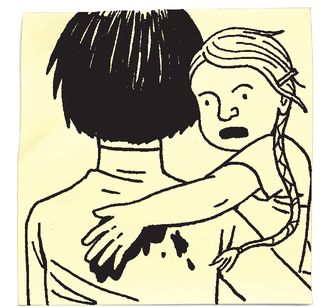

Her shirt was splashed with red.

I found out later that I had severed the artery.

Two cops came and rushed me to the hospital in their squad car, with the sirens on.

My teacher sat with me in the backseat, squeezing my wrist behind the cage, and I watched everyone pull over for us.

My room at the hospital had a painting of Snow White and the seven dwarfs on the wall.

Dopey and Doc were the only ones recognizable; the rest looked sinister and strangely alike.

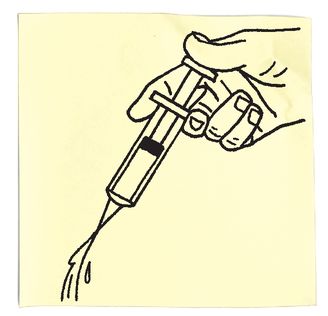

One of the nurses had a big plastic plunger. She filled it with ice water and then squirted the ice water into my open wrist.

It hurt. I screamed. It took five nurses to hold me down on the table.

One was on my legs, one was on my right arm, one was holding my head, and two were holding down my wrist.

My parents were at a Red Sox game. This was in 1978—no cell phones.

Every once in a while, one of the nurses would stick her head into the room and say my parents were on their way.

But they never came.

A doctor walked in. He had a small round mirror strapped to his head. He was friendly.

Then I kicked him in the face, and he wasn’t so friendly anymore.

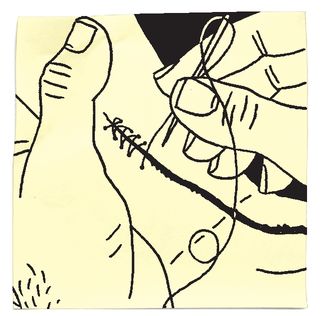

He took out all the pieces of the grave from inside me and then he started sewing.

It felt like he was going to sew my whole arm up.

The nurses wrapped my wrist in rolls of white bandages.

When they were finished, one of them gave me the plastic plunger.

My teacher brought me to her apartment and put me on a couch with a blanket.

My hand swelled up and I couldn’t bend my fingers.

She made me a cup of tea. I couldn’t drink it.

I felt like I’d aged a century.

Like I’d traded bones with one of the bodies in the graveyard.

I waited on the couch all afternoon, until the Red Sox game was over, and my parents went to pick me up from kindergarten, found out what had happened, and came to take me home.

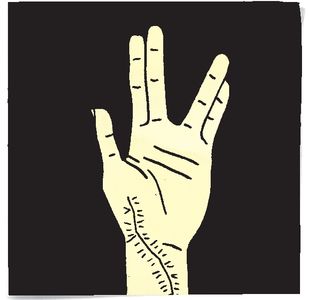

My left hand ended up being fine—only some nerve damage, so I can’t put my middle finger and ring finger together.

When I try, the fingers get stuck and I look like I’m delivering the “live long and prosper” salute from Star Trek.

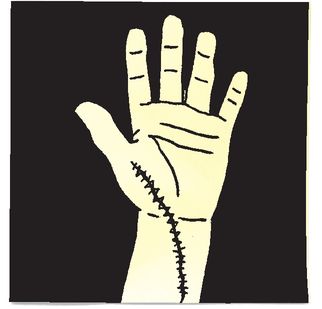

There’s also a scar that twists from the heel of my hand down past the tendons and blue veins. It looks like a centipede trapped under the surface.

The marks from the stitches fan out in all directions. And the skin there always feels tight.

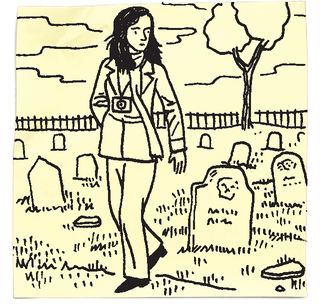

A few years ago, I went back to the cemetery where it had happened, and took some pictures. It felt like walking into a dream—everything was out of perspective.

The family plot where we used to play was a tiny stone wall that only came up to my knees.

There was a bump in the middle of the yard that I remembered being an enormous hill. The whole place was different, but also the same.

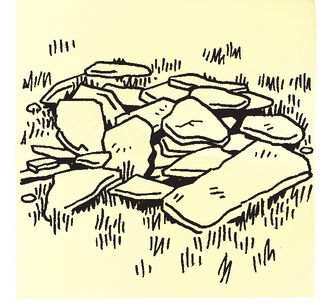

I tried to find the grave where I had fallen. I was curious to see whose name had gone into my body. But the broken stones were unreadable, just piles of slate.

There was no way to know who was there under the ground. Hundreds of years had passed since anyone who remembered them had lived.

The bodies were still there, though. I could sense them when I crossed over.

And the stones were still beautiful.