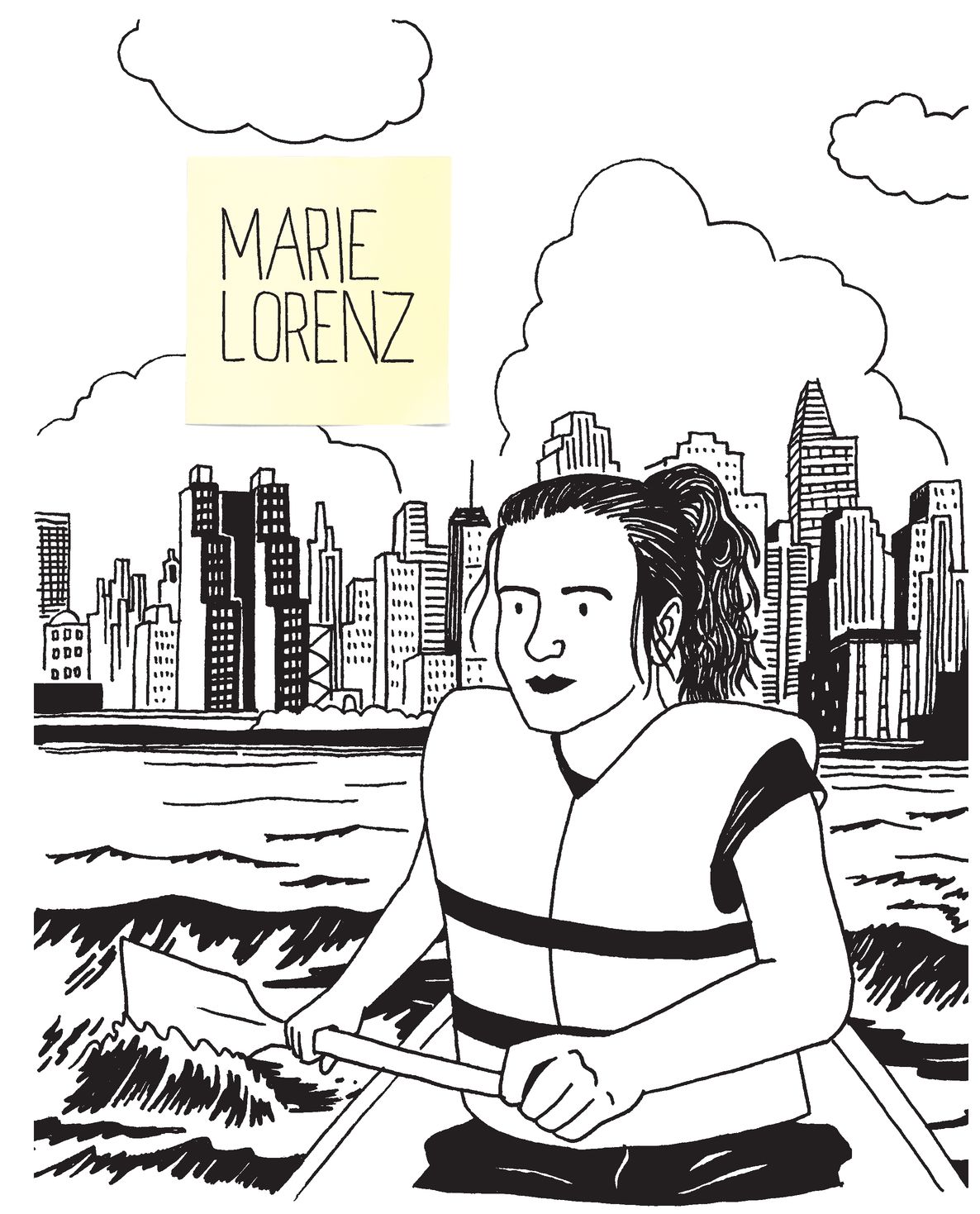

Shipwrecked

by Marie Lorenz

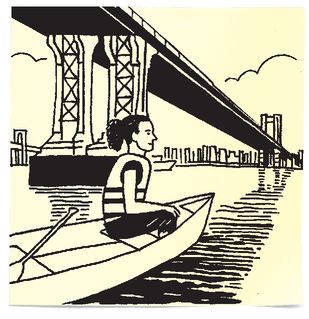

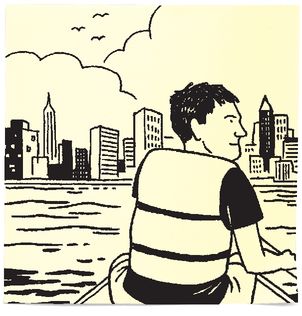

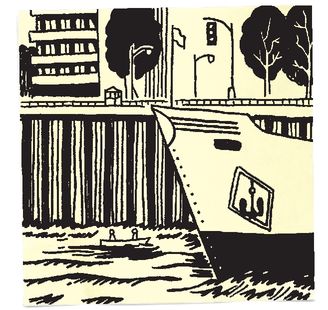

I have an art project called the Tide and Current Taxi, in which I ferry people around New York City in a boat I made.

I call the boat a taxi because I’d like for people to use it as an alternative means of transportation around the city.

I call it an art project because I rarely get people where they actually want to go.

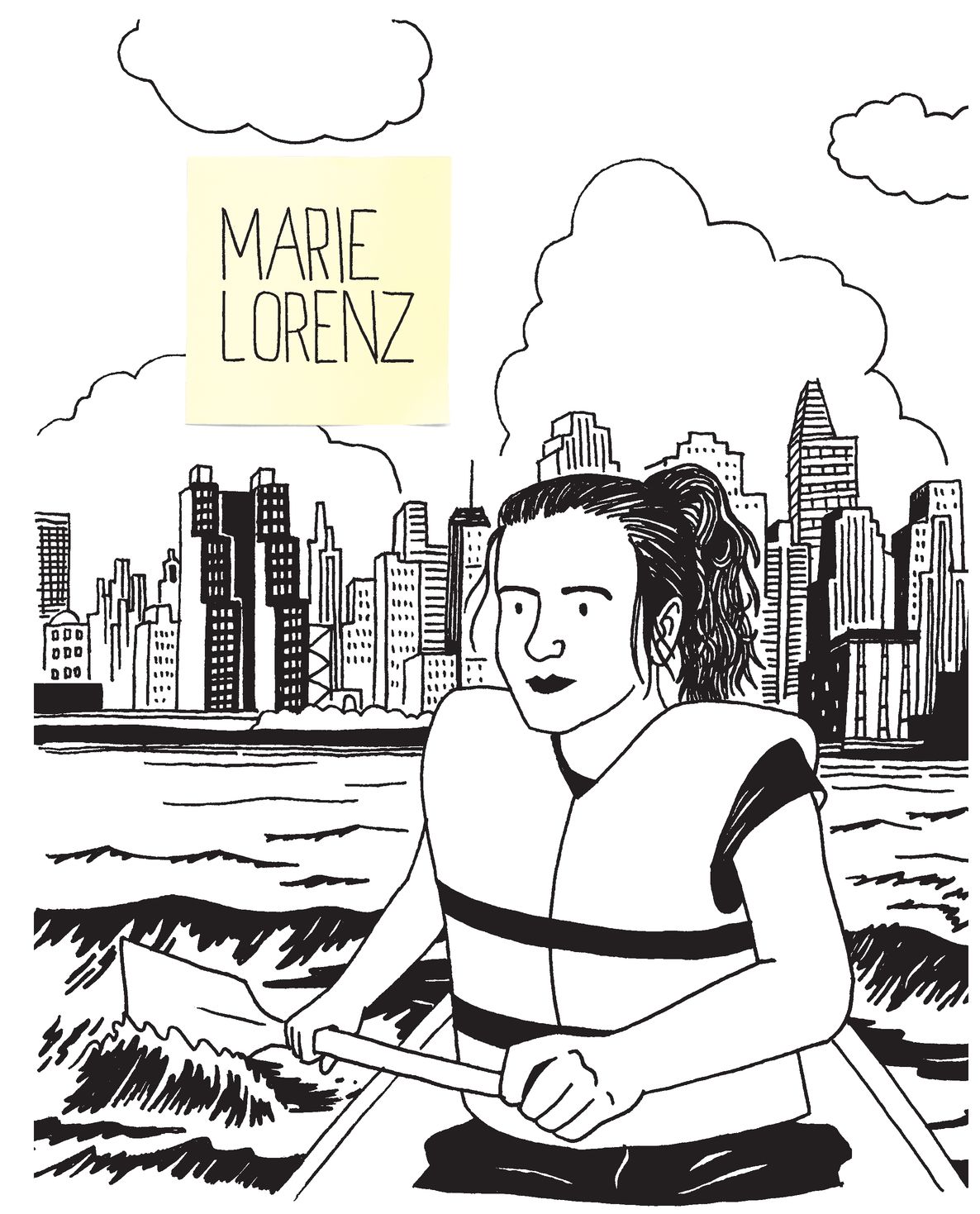

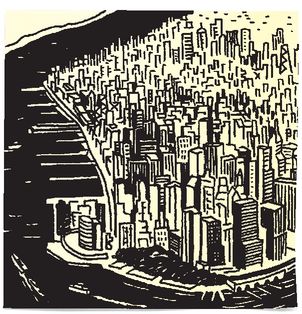

Manhattan is an island, situated in a huge tidal estuary, and even the distant boroughs are connected by a system of rivers, creeks, canals, bays, and inlets.

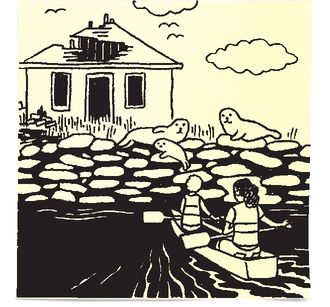

For example, you can push off from a boardwalk in Staten Island and float across the Lower New York Bay to Swinburne Island, where you can see migrating harbor seals resting on their way to Nova Scotia.

You can also paddle from a pier in Harlem, cruise for a mile along shallow Dutch Kills Creek, and dock on quiet North Brother Island.

North Brother is now a bird sanctuary, but on it sit the ruins of an abandoned hospital that was used to quarantine New York’s most contagious and criminal patients.

The small house where Typhoid Mary was imprisoned in 1915 is still there, forgotten and rotting away.

When I moved to New York in 2005 I started sailing to these sorts of “secret” places and became fascinated by the strength of the current in the harbor.

It seemed possible that with a little planning and an understanding of tidal charts you could simply hop in a boat and ride the current wherever you needed to go.

I’ve been building boats for years. My earliest efforts were in art school—simple dinghies made out of scrap plywood.

Over the years, my skills have developed and my boats have become more elaborate.

But for the taxi I wanted to build something simple, light, and durable. So I made a plywood double-ender, fourteen feet long and slightly wider than a canoe.

Sturdy yet buoyant. Pretty yet practical. Just like New York City itself.

With my plywood taxi complete, all I needed was a passenger and a destination.

I sent an e-mail solicitation to everyone I knew. The message got passed around and I eventually heard from a friend of a friend of friend, named Joe Potts.

Joe wanted to take my taxi from Williamsburg to Manhattan—a quick commute across the East River, perfect for my project’s maiden voyage.

I met Joe a week later with my boat on an abandoned beach near North Sixth Street in Brooklyn.

The current was flowing northward, so I proposed floating along the Brooklyn coast until we were parallel to Fourteenth Street in Manhattan.

At which point we could paddle across the river, dock, and grab some coffee.

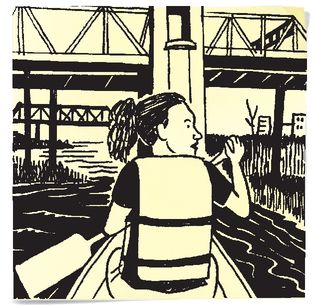

Joe took a seat in the bow of the boat, I took one in the stern, and off we went.

The tide did carry us north as planned, but the wind pushed us much faster than I’d anticipated.

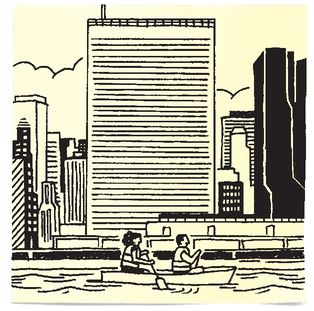

Before I knew it we were parallel with the United Nations building, swept a good thirty blocks north of Fourteenth.

We made our break for Manhattan just past Roosevelt Island, a strip of land between Manhattan and Queens just a few blocks north of the UN.

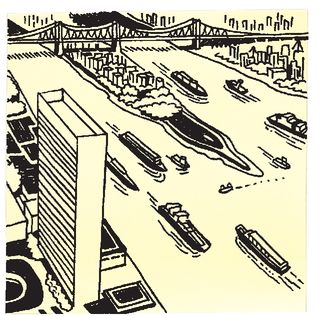

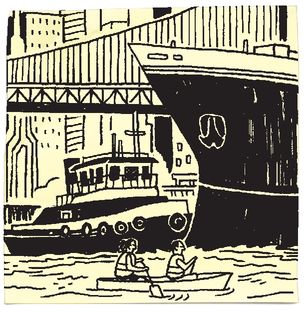

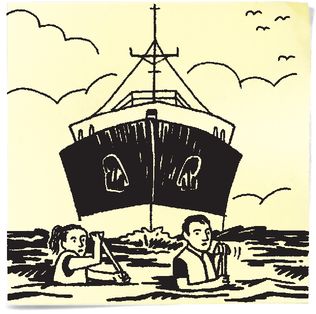

As we crossed, we found ourselves in the path of ferries and tour boats pulling in and out of a high-traffic dock nearby.

In open water it’s not that difficult to pilot a small boat through the wake of a big one: You sort of paddle in at an angle and let the waves roll under you.

But this wasn’t open water, and as we neared Manhattan we got into some trouble near a steep iron seawall.

The wake from the larger boats ricocheted off the taxi in steep triangular waves that were impossible for us to ride through.

Soon water was violently crashing over both sides of our boat.

“Worst-case scenario,” Joe yelled to me, “we flag down another boat to help us, right?”

“Joe,” I said, “this is the worst-case scenario.”

We paddled as hard as we could away from the seawall and back toward Roosevelt Island while the boat’s hull rapidly filled with water.

We tried to bail out the water but it was no use.

At some point the boat just sort of disappeared from under us and we found ourselves swimming in the East River’s shipping lane.

Huge boats were bearing down on us from the north and south, oblivious to our struggle.

As we swam, I tried to keep my mouth shut. The water was warm and salty and smelled like a sewer.

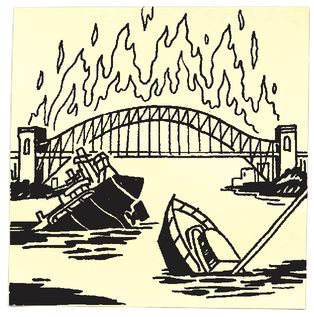

We were five hundred feet from Roosevelt Island but the tide was pulling us north, away from the shore, toward Hell Gate, an infamous tidal strait known for swallowing boats whole.

The boat had capsized; I tried to tow it behind me as I swam but the pull from Hell Gate was too strong.

I was exhausted from paddling and weighed down by my clothes and shoes. Somewhere around the Fifty-ninth Street bridge, Joe convinced me to let go of the boat.

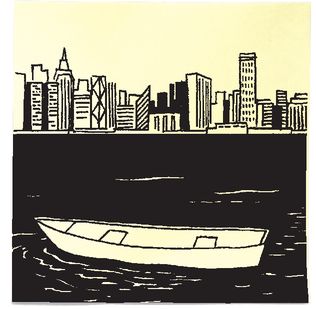

As it drifted away my heart sank. The prettiest boat I had ever made—an entire summer’s worth of work—down the drain.

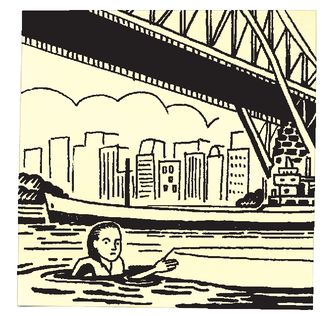

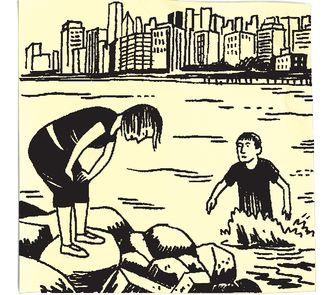

Free of the boat, we swam to Roosevelt Island and dragged ourselves up the rocky embankment.

As we sorted through our stuff—dead camera, dead cell phone, wet wallet—we started to laugh. The situation was incredible.

There we were, shipwrecked and stranded on an island—all within a mile of Times Square.

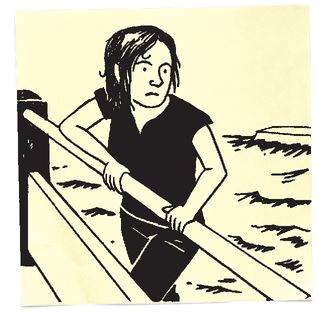

As we walked toward the Roosevelt Island subway stop, I caught sight of the boat floating upside down in a tangle of gear.

The tide was still pushing her north, but she seemed to be matching our pace, almost lingering alongside us.

I couldn’t abandon her.

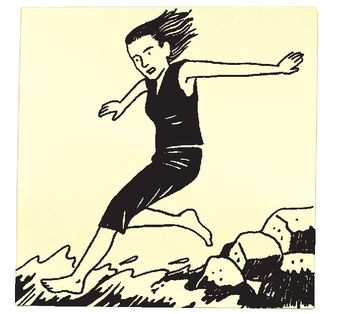

I kicked off my shoes, tore off my life jacket, and dove back into the toxic, smelly river.

It was much easier to swim without my shoes or life jacket and I was able to haul the mess back to shore pretty easily.

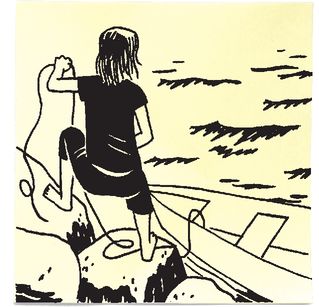

But now that I had my boat back, I had to ask myself: What was I going to do with it?

I’d been a terrible sailor and had put a stranger at risk. The answer was clear.

My taxi service was over after one lousy trip.

Later that night, back in Brooklyn, I sat down at my computer to send out a mass e-mail telling all my friends and potential passengers about the demise of my project.

But before I hit Send, I got an e-mail from Joe’s roommate. Joe had told her about the shipwreck, and how we almost got cut in half by a tour boat and nearly drowned in the East River.

He’d also said it was the most fun he’d ever had in New York.

“I’d love to come along on the next trip,” she wrote. “And I can swim.”