Big Black Bird

by Jeff Simmermon

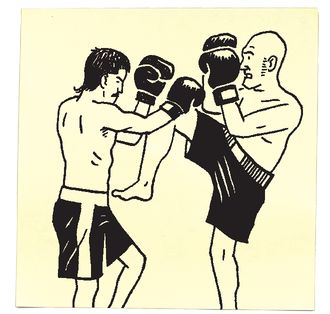

I kind of had cancer last summer, for a little bit. At first, the only sign was that I’d been moving much more slowly than usual during Muay Thai training.

I was having trouble getting the pads to the right place in time to catch my sparring partner’s kicks. I thought it was because I was pretty sleep deprived and stressed out at work.

Then, during a sparring session, this little Dominican guy a foot shorter than I am kicked me square in the nuts and I nearly passed out.

I went home, and then to the doctor, where we discovered a tumor roughly the size and density of a Cadbury egg growing in the center of my left testicle.

“This has got to come out soon,” the doctor said.

“How soon?”

“Tomorrow.”

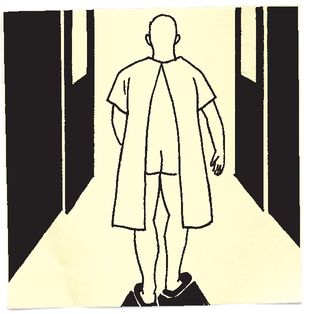

When I had my tonsils removed I was drugged into submission in another room and wheeled into surgery.

This time, it was very important to the doctor that I walk into the operating room under my own power. I don’t think I’ll ever understand why.

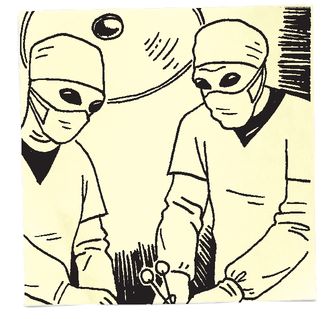

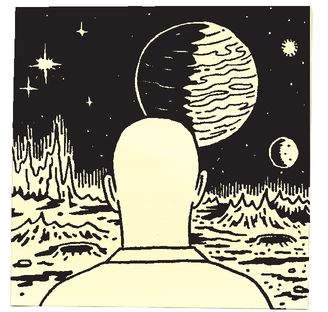

It felt like walking into my own autopsy in the belly of a flying saucer.

Surgical white light blazed off the tips of every shining scalpel and beamed hot right on my brain’s fight-or-flight reflex.

Everyone in the room was garbed up for surgery in the same mask, gloves, and robe.

I stood there in the room, freezing in the sterile air, trying very hard not to run.

Suddenly all the doctors turned to look at me simultaneously, like aliens pretending to care. One of the taller ones said in a cool, flat tone, “Welcome, Mister Simmermon.”

“We’ve been expecting you. Everything is going to be fine. Just get up onto this table and relax.”

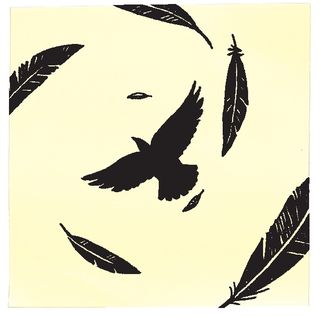

The corona of light beyond the surgical lamps faded fast to a deep-space blackness.

The blackness took the shape of a large bird. The black bird rose up and spread its wings, folding me into a void between its wings and carrying me deep into the mother ship.

They cut all the cancer out by simply removing my left testicle. No more surgery, no chemo, no radiation. I should have felt lucky, and I did, sort of.

I’d only had cancer for a short time, and it was over.

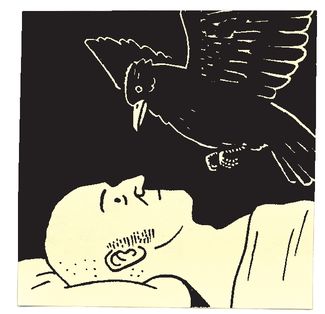

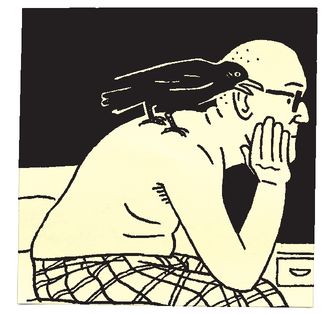

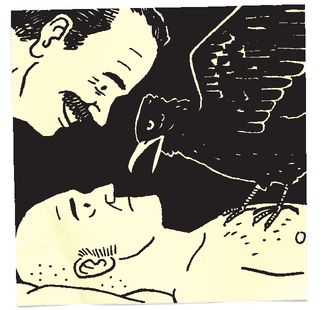

As I was lying in bed at home that first night after surgery, the big black bird from the hospital fluttered down and landed on my chest.

It crept up my torso and balanced its icy claws on my throat, then tilted its beak into my ear and began to whisper.

It said, “Your body might be healthy now, but things are going to be different from here on. People are going to find it really, really hard to relate to you.”

“Nobody’s going to understand you. So go easy on yourself. You’re never going to stop needing people, but eventually you’ll get used to feeling all alone.”

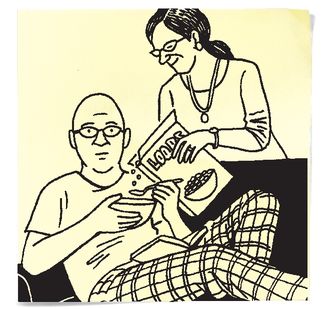

Family and friends circled around me and showered me with love and affection. My mother came and stayed with me for a week, and I got to be her child all over again for a little while.

My coworkers sent us a week’s worth of free meals so we could focus on spending time together.

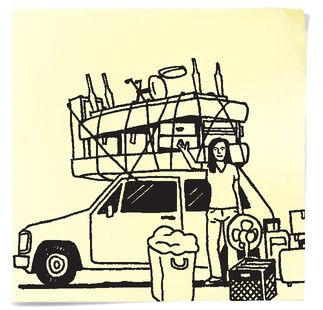

And my girlfriend decided to move up to New York from Washington just to live closer to me.

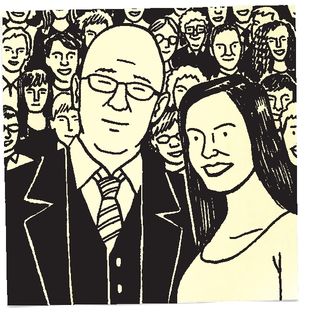

And beyond that, I discovered so many beautiful, wonderful people who had been right next to me all along, quietly at the periphery of my life.

If you’re feeling lonely or unloved, I can’t recommend cancer enough. It really gives you the boost that you’re looking for—in the short term, at least.

The support was amazing, but eventually I found its limits. There was only so much these people could understand; nobody else had suddenly lost a testicle or any other body part.

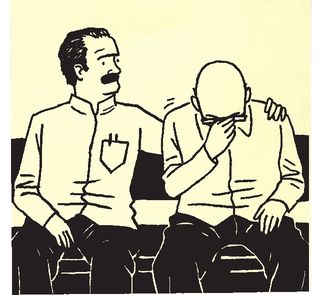

I told my best friend, “Dude, I am so depressed right now.”

“Well, good,” he said. “You just got one of your balls cut off. If you’re not depressed, you’re crazy.”

Once my body healed, I returned to work, started going back to the gym and doing all the things that I’d done before I got sick.

I felt like the last man dancing after somebody unplugs the jukebox and turns out the lights.

I looked perfectly healthy. People came up to me and said, “You’re looking great, man, looking real great! How are you feeling?” There was no right answer to that question.

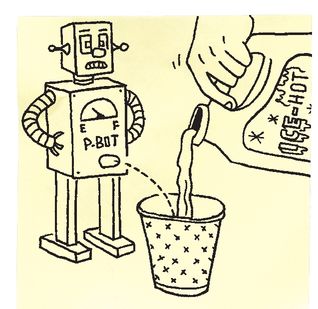

You really don’t want to tell someone, “I feel like an android that has been programmed to act just like me.”

I felt like a photocopy of a photocopy, conveying the essential information but blurred and distorted, fading away at the edges.

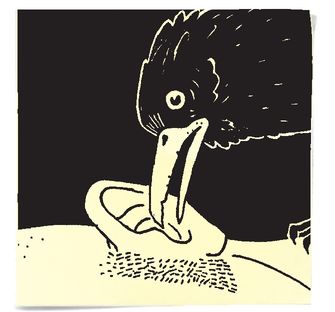

The bird came to visit me every night, as soon as I was in bed and alone. One night it said, “You’ve lost your passion, man. You used to be so vital and full of energy.”

“Now this weird Jungian thing happened to you and it’s like you got stripped of something invisible. And you can’t even be bothered to mourn the loss.”

“I know, you’re so right,” I said. “It’s like I’ve been half-neutered.” “Well, you have,” the bird replied. “And it’s not coming back, either.”

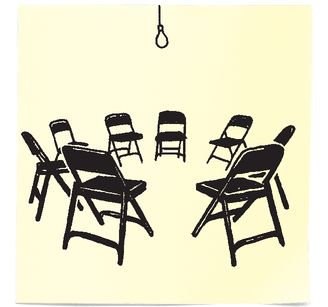

I asked my nurse at Sloan-Kettering if they had a support group for this sort of thing. The nurse said, “It’s funny, we really don’t.”

“The best cancer center on earth and you guys can’t get some folding chairs and shitty coffee together? You sure about this?” “We tried, but nobody came.”

“This kind of cancer mostly affects young guys, and we find that they really don’t want to talk about it. You might get some value out of a different support group, though. Maybe you could—”

“What,” I interrupted, “take over a brain cancer one and make it all about me?”

Sometimes I would see children with cancer in the waiting room when I went to get a CT scan.

I’d see them sitting there, so small and gray and submitting so bravely to their fate, and my heart would drift even lower.

I was so physically healthy and these kids weren’t ever going to drive. Poor me.

Recursive self-abuse; there’s nothing quite like it—beating yourself up for beating yourself up.

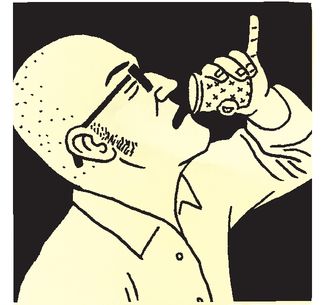

When you get a CT scan, you have to arrive an hour early in order to marinate your body tissues in a pink liquid.

It tastes exactly like robot piss sweetened with antifreeze.

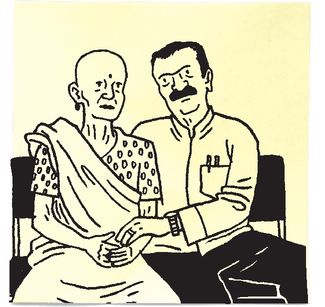

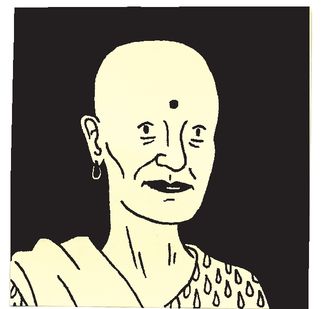

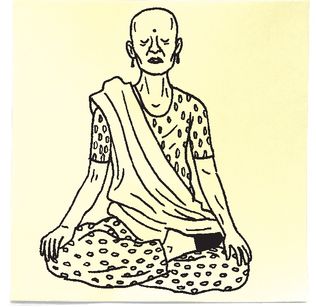

During one of my many trips, I was sitting in the waiting room sipping a bottle of this sweet secretion when I noticed an Indian couple across the room.

The woman was completely bald, and I am fairly certain she’d had a double mastectomy.

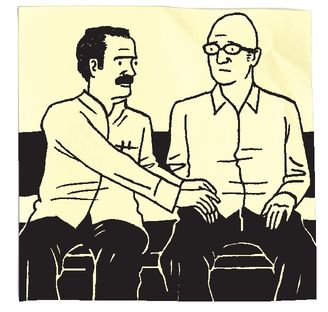

She crossed her legs into a prayer pose and began to meditate. Her husband moved to give her some space and sat down next to me.

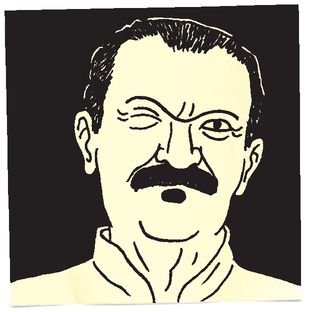

Shortly after a nurse took the woman away, her husband elbowed me and said, “So, what are you in for?”

told him, and he winced. Every guy does it, every time.

Then he said, “You know, in my religion, we believe in destiny. We believe that things happen to you for reasons you may not understand.”

“They just happen and you choose the way in which you adjust. Given that, I’d say my wife’s cancer hasn’t been an entirely bad thing.”

“In twenty-seven years of marriage there are ups and there are downs, and when she got diagnosed, we were on a down.”

“Now we are communicating better, and we’re closer with each other and our children. Our grown children—who have left the house and are not even Hindu anymore—we are closer than ever.”

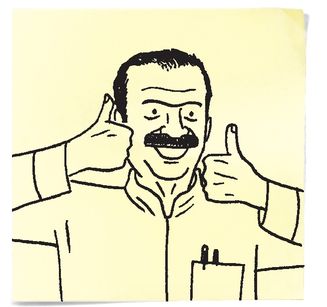

He turned to me and clasped my hand tightly with both of his, then looked me right in the eyes.“Something good is going to come of this,” he said. “You’re young and strong and you’ re going to live.

“And all you have to do is find it, then allow it into your heart. And once you let that thing into your heart, you will really know what it is to live.”

For the first time since my diagnosis, and probably much longer than that, I was able to cry, let it all out, all that pent-up emotion after months of being strong for everyone but myself.

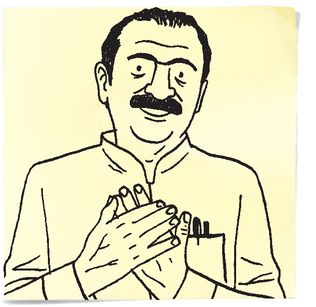

Then the nurse took me away and the guy looked at me and gave me two huge thumbs up, his mustache stretched wide over a tremendous toothy grin.

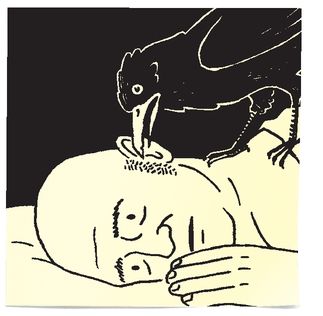

I see him all the time, pretty much every night when the big black bird shows up.

If I close my eyes and concentrate very hard, I can conjure his Cheshire mustache, hovering over that big black bird on my chest.

One day I’m going to believe him, and that big black bird is just going to fly away.