Cow the Bird

by Daniel Engber

If my mother was killing off my pets one by one with her bare hands, then at least she made it look natural.

An intestinal parasite, a kidney stone, too many fish flakes; the animals had a habit of dying when I wasn’t around.

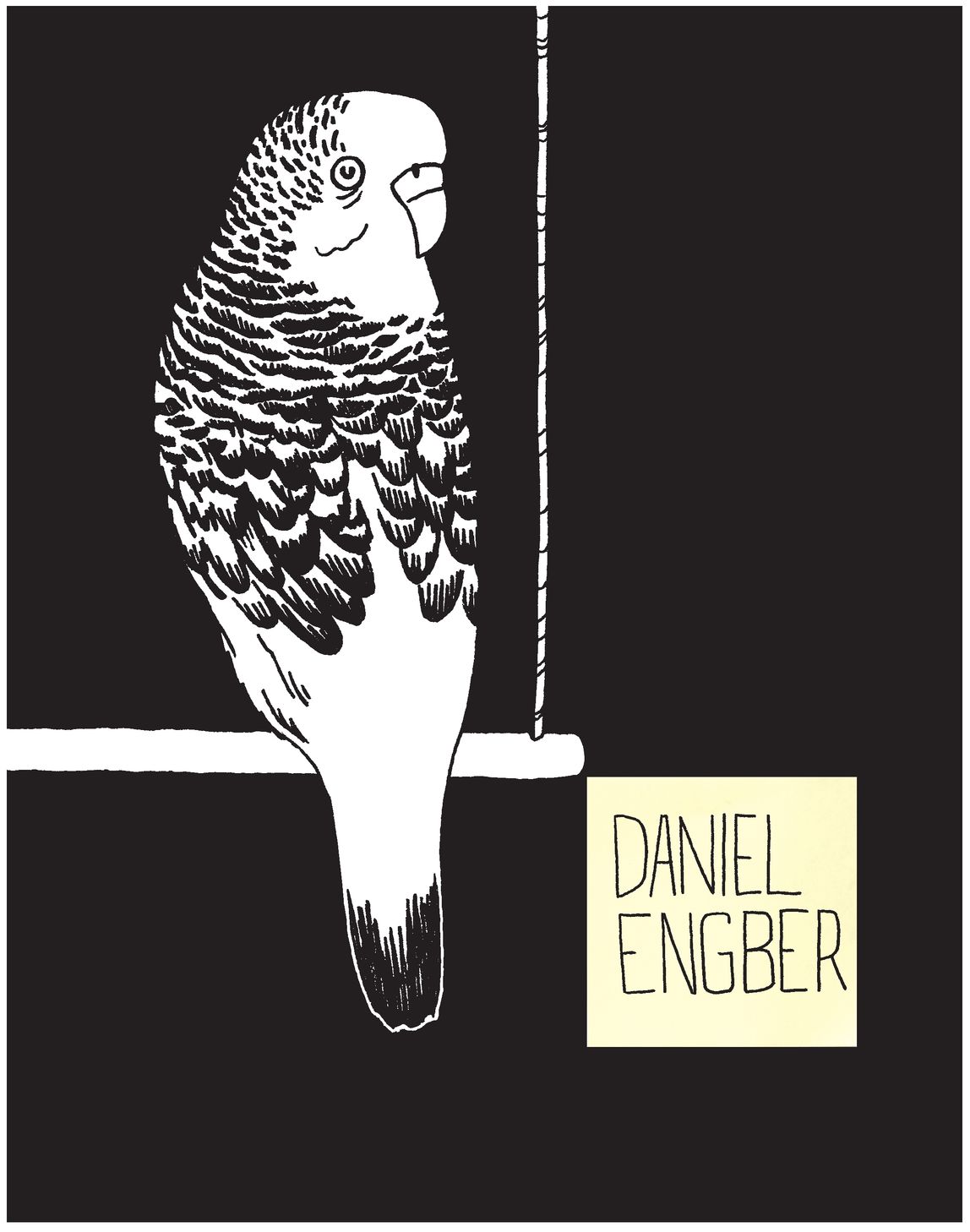

There was the fish—a minnow scooped from the Hudson River—who vanished one afternoon from the coffee jar on the windowsill.

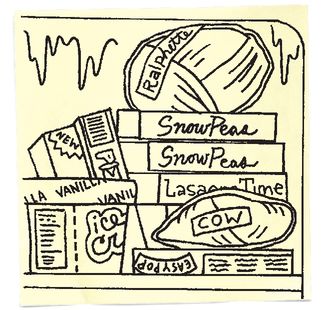

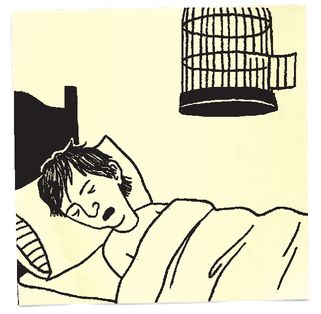

And the guinea pig, Ralphette, who disappeared from her cage in the middle of the night.

By the time I woke up, she was wrapped in paper towels and newspaper, sealed in a Ziploc bag, and wedged in the back of the freezer.

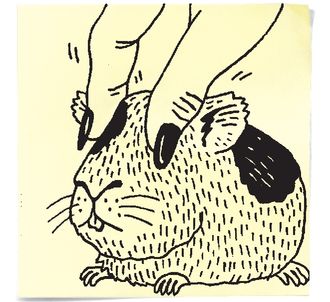

Mom was the animal undertaker, pressing tiny eyelids closed with her fingertips while the rest of us were sleeping.

I was over at a friend’s house on the night she came for the bird.

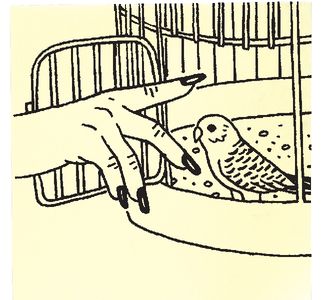

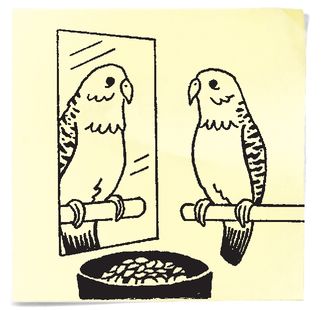

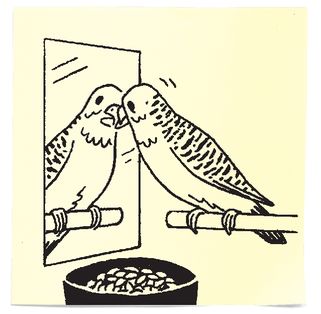

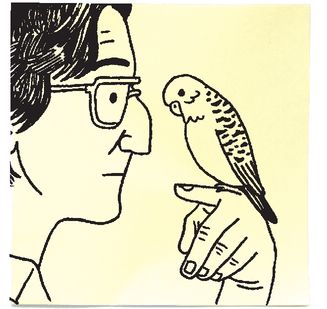

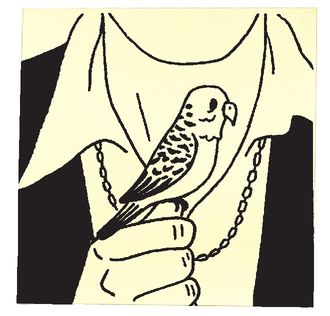

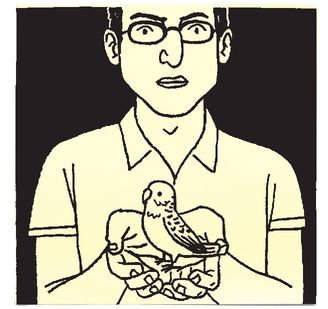

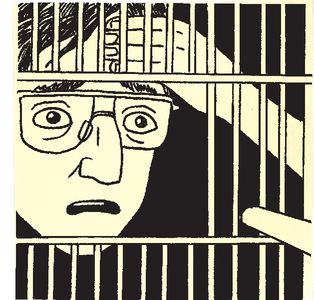

Cow—that’s my parakeet—spent two years in a cage next to my desk, with a mirror affixed to the bars.

He would be the first of many birds to pass a short, miserable life under my care, but at the time he seemed like a special case.

A sad sack. I remember him chirping at his own reflection, and spitting up mouthfuls of seed so the mirror bird would have something to eat.

As long as we lived together, Cow never once sang a note. He honked, though, at high volume, interrupting my homework and keeping me up at night.

If he’d been able to mimic human speech—like parakeets are supposed to—he might have learned the phrase shut the hell up, or the words die, die, die.

When the bird was healthy, I tried to browbeat him into getting sick.

When he got sick, I did what I could to make him better.

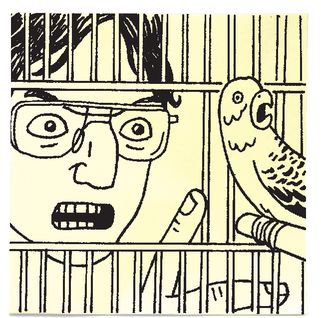

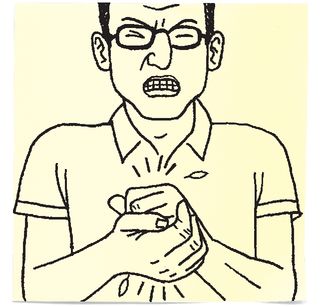

We brought Cow to the vet when a clump of dried guano began to accumulate on his backside.

He wasn’t drinking from his water dish, so we had to feed him medicine through an eyedropper, forcing the fluid into his beak until it bubbled from his nostrils.

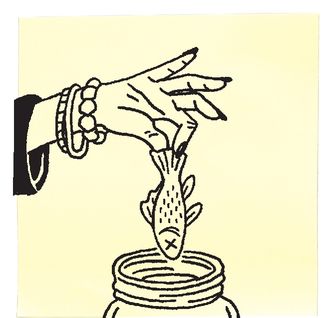

I left my mother in charge of this treatment on the night I went to David’s house.

When I got home the next day, Cow was twelve hours frozen. He’d drowned on the antibiotics, my mother told me.

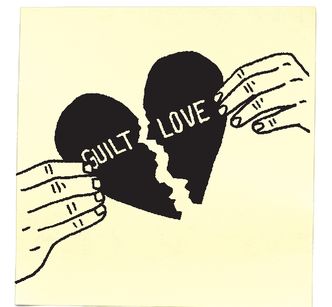

I believed that story of a death by good intentions for half my life. It seemed like a parable of what happens when guilt starts to feel like love.

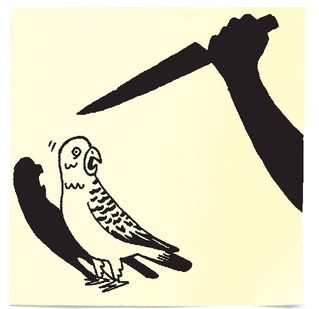

But it wasn’t true. Cow hadn’t died because we’d tried too hard to save him. He had been murdered.

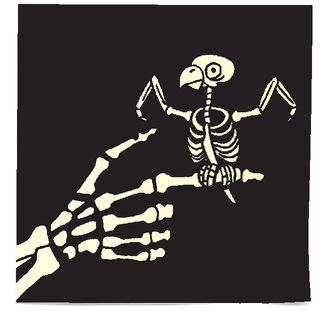

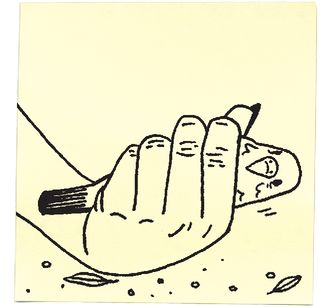

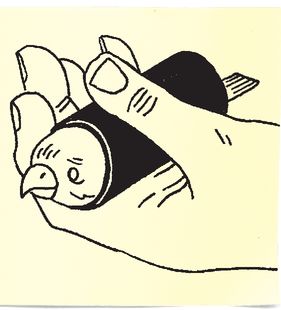

My mother had taken his hollow-boned head between her thumb and forefinger and twisted until his neck broke.

A word on methodology: There are plenty of humane ways to kill a full-grown parakeet.

Poultry professionals use metal tongs to wring birds’ necks, or they drop the animals in electrified water pools, or carbon dioxide tents, or wood chippers.

When the British government culled six million farm animals during a foot-and-mouth outbreak in 2001, the military officer in charge said it took more planning than the Gulf War.

One member of Parliament suggested gathering the animals together and then dropping napalm on the heath.

My mother has always been good with her hands, though. She’s artsy-craftsy. In the old days, she played guitar and wore her hair like Joan Baez.

Now she spends her time making quilts for her grandchildren.

In between, when I was growing up, she was a chain-smoking Wall Street executive.

Her colleagues wore tweed and bowties; she wore a silver necklace from Santa Fe decked out with grizzly bear claws.

It was fifteen years before I learned the real story of Cow’s demise. My dad—the only living witness to the crime—gave his testimony at Thanksgiving dinner.

My mother had entered my room with the eyedropper, he explained between bites of roast turkey.

She’d planned to administer the dose of ornacycline according to protocol. But she found the pitiful bird lying on the bottom of its cage, puffing its feathers.

She put down the eyedropper and snapped its neck.

My mom corroborated the story, and then assured us she’d made no other attempts on the lives of family pets.

Whether she was guilty of serial euthanasia or she’d merely whisked away the animal corpses before anyone saw them, we all knew that she had done her best to make death invisible.

Cow the bird was living in my bedroom until the night when he wasn’t. That’s how we dealt with tragedy: When people got sick, they disappeared.

I remember one day my brother was gone from the apartment.

Then all of a sudden he was back, with a bandage over one eye. I found out later—months later—that he’d had a brain tumor.

The Thanksgiving confession came as a shock, though I’d just spent months killing animals myself.

As a graduate student in neurobiology, I’d cut open the brains of mice, kittens, and monkeys; dozens of living things had died in my hands.

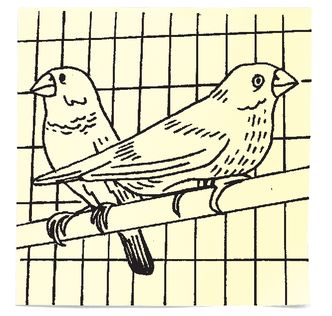

But in the end, it was the birds that drove me away from science. They lived in the basement, in cages stacked three high.

Our lab was studying the Bengalese finch, a songbird that’s known for musical improvisation.

Other species, such as the zebra finch, learn one tune in childhood and repeat it forever after; the Bengalese likes to riff.

Most of the studies involved putting a male and a female in the same cage and listening to the courtship songs.

Sometimes we recorded from their brains using electrodes.

But my job, the one assigned to me when I joined the lab, was to conduct a more invasive experiment:

A gross excavation of the avian neuroanatomy, and wholesale removal of its cerebellum.

If I succeeded and the bird survived, how well would it sing?

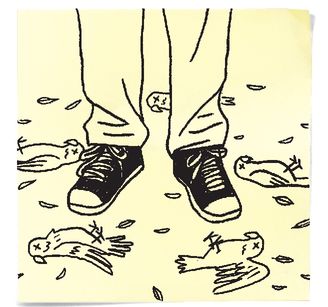

I spent weeks practicing on live subjects, as one after another succumbed to fatal hemorrhages.

After a while, it started to feel like a career unto itself: Everyday, I’d wake up at 8:00 a.m., eat breakfast, pack a sandwich, and head into the lab to kill more birds.

We’d clamp a finch to the table, place a halothane gas mask over its beak, and start plucking the feathers from its head.

One bird would be dead by lunchtime, and then another would die in the afternoon.

A small flock of cadavers piled up in the biohazard bin, until eventually my technique improved.

A few birds even survived the operation. Back in their cages, they’d wobble to their feet with bits of seed stuck to their scalps.

And then I’d watch, taking notes, as they tottered in circles, around and around, until they died. Not one of them ever sang a note.

If my mother was Jack Kevorkian, then I was Josef Mengele.

Now, I suppose my own history of violence should have helped put Cow’s story in perspective.

That was a mercy killing, a coup de grâce, while the finches in my lab had been in perfect health.

But somehow the brain studies only made my mom’s betrayal seem worse. She’d killed my parakeet so I wouldn’t have to see an animal die.

And then I found myself in the middle of a Bengalese massacre.

I don’t know if I’d have been any wiser for seeing Cow wither away in his cage.

It’s not like my mother had deprived me of some developmental milestone—a first dead animal, or a bar mitzvah pet murder.

Still, I couldn’t shake the feeling that the woman who was playing the role of my mom had gone wildly off script.

Here’s how a mother stays in character: She takes you to the beach and drapes you with seaweed.

She makes you cinnamon toast.

She dresses you as Pinocchio for Halloween.

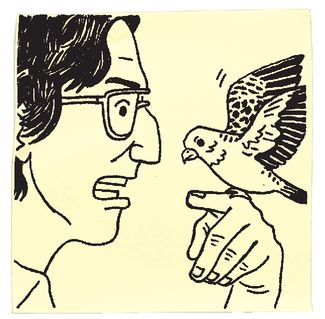

On your eighth birthday, she comes into your room with a blindfold, and when you take it off twenty minutes later you’re at the pet store.

And here’s how a mom scares the shit out of you: She buys that little green bird with the speckled crown, and breaks its neck.

Knowing Cow’s fate wouldn’t have kept me from going to graduate school, or from suctioning out finch brains with a vacuum tube. But I do wish Cow’s death hadn’t been such a secret.

I wish I’d seen my mom in action, like one of those women who finds her baby under the wheels of a 4x4 and suddenly gains Hulk-like strength.

Maybe my mom sensed that I was in a certain kind of danger back then, and she transformed, for an evening, into someone else. Instead of turning super strong she turned super tough.

It’s a horrible thing to crush a small animal to death. Believe me, I know.

In the end, I guess that’s what makes it so special. There’s nothing like a mother’s love.