All Happy Families

by Jonathan Goldstein

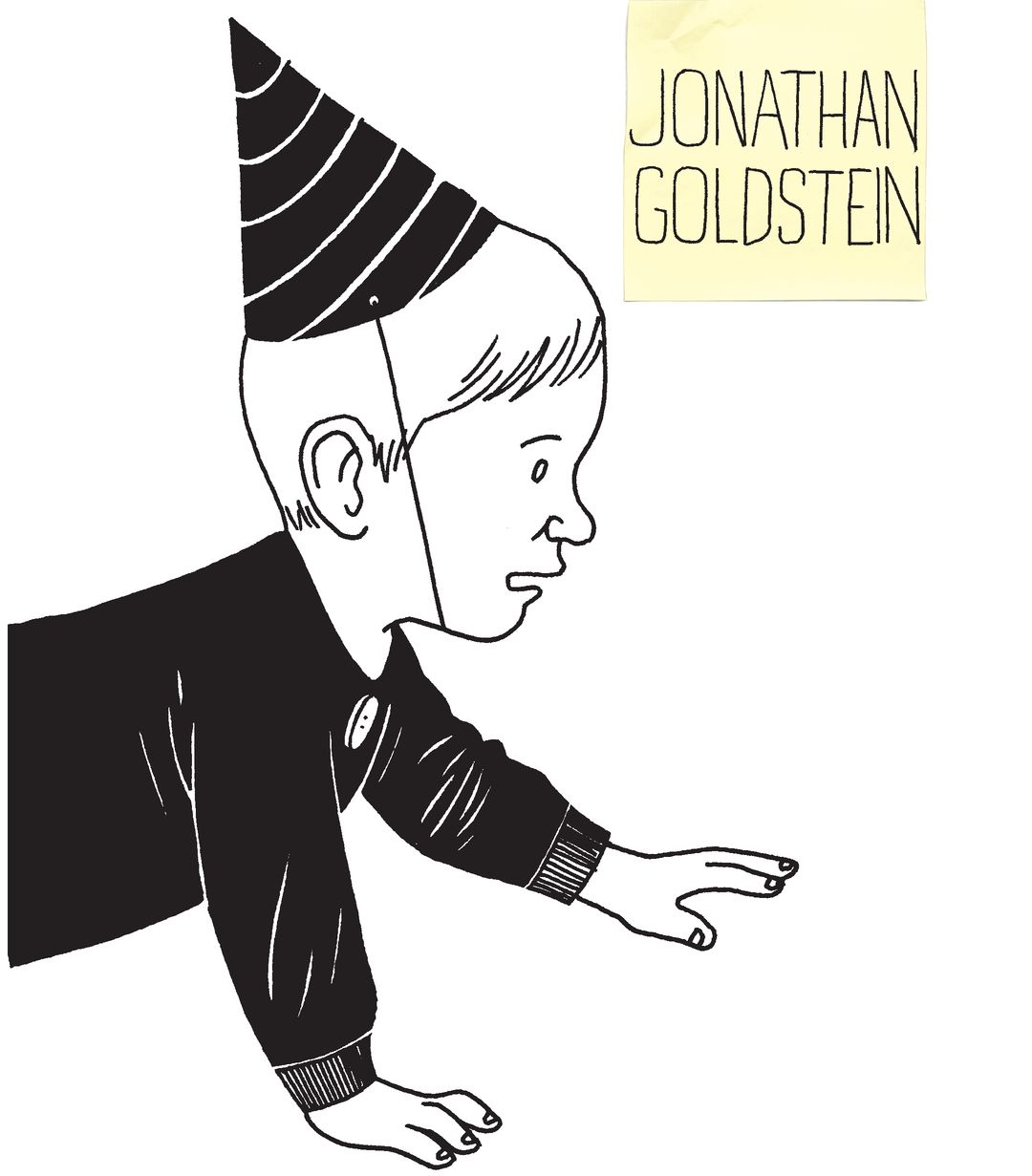

My sister was pushing forty when she announced her pregnancy.

“It’s a miracle,” my mother said. Dina Goldstein had had me in her teens; she believed in early starts.

Rising at 5:00 a.m. to dust ceiling fans and fireplace logs, she was sprung from the mold of shtetl women past who cleaned, loved, and worried with great ferocity.

Which is to say, she’d been waiting to be a grandmother since her twenties.

And which is also to say, with my sister’s good news, the pressure was off me.

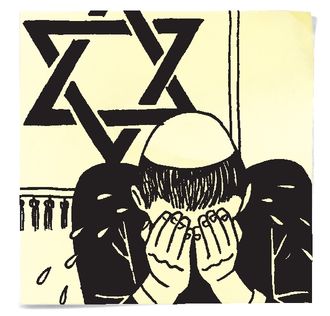

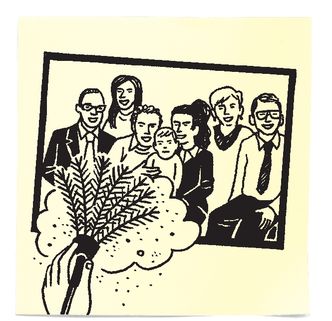

We’re not the closest family in the world—get-togethers are usually reserved for funerals and the Jewish high holidays, both equally mirthless affairs.

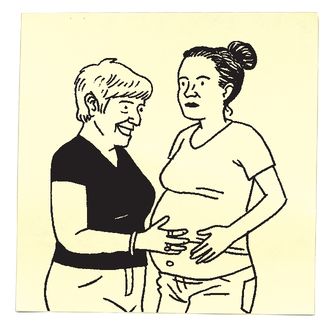

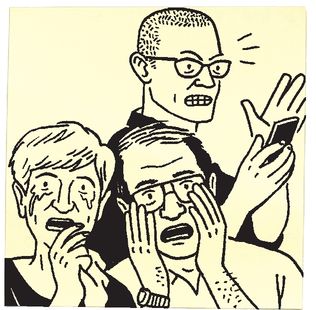

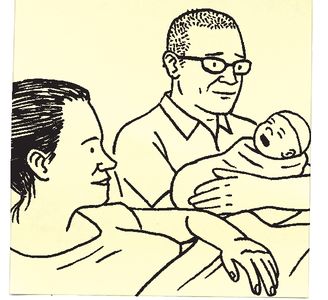

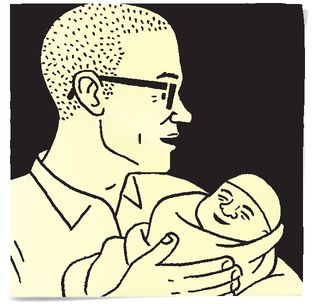

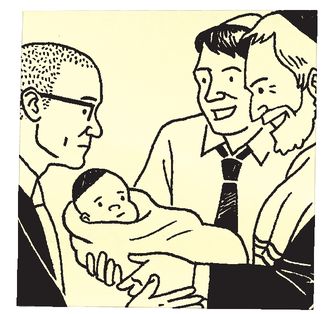

On the blessed day of the baby’s arrival, we all meet up at my sister’s hospital room.

But just now, I’ve never been in a room where so many members of my family are this happy all at once.

Usually, maybe one or two are happy at any given time, while the rest hold down the fort.

Remaining dyspeptic and dysphoric, or boldly struggling to maintain a nice, even level of dispiritedness.

Tolstoy once wrote that every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way, and happy families are all alike.

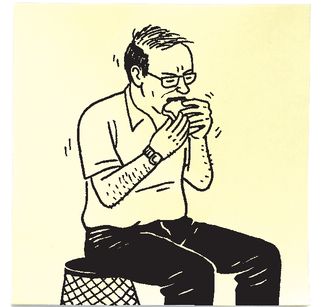

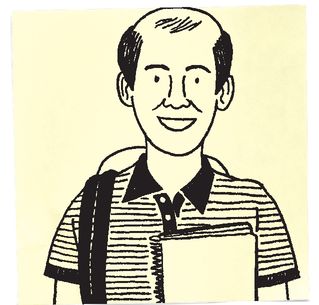

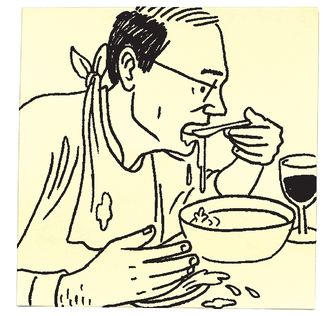

This is not so, as is evidenced by my father, who is smilingly biting into a home-brought chicken sandwich while seated atop an upturned wastepaper basket.

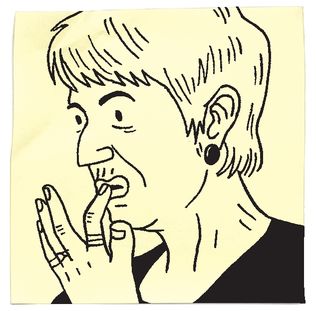

And my mother, who is rubbing disinfectant soap onto her lips in preparation to kiss the newborn.

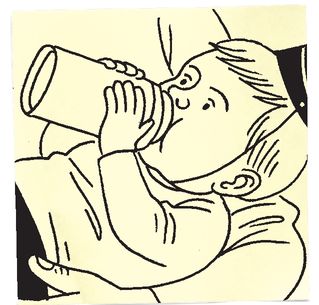

We all stand around for hours, happily staring at the baby and clutching our chests.

How strange to feel yourself falling in love with someone you’ve only just met.

And how endlessly fascinating it is to watch someone getting used to being alive.

Though perhaps even more fascinating is watching someone getting used to being a part of our family.

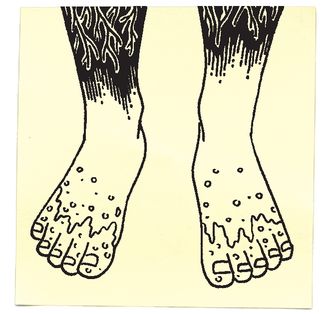

The male pattern baldness that starts at twelve.

The foot fungus that rises up to the thighs and the hemorrhoids that descend to the ankles.

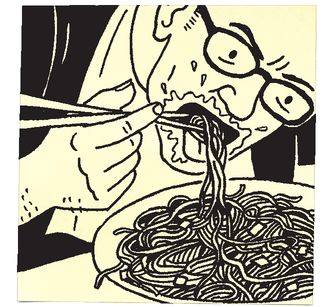

Not to mention the messy eating.

Legend has it that one time my father kept an egg noodle hanging from his lower lip for the duration of the July Fourth weekend.

If he could have only lasted a few days longer he might have ended up on the Johnny Carson show, seated on the couch alongside the guy who had hiccupped for forty years.

But to look at him—Justin Mitchell, so little and brand-new—and to even think these things feels wrong somehow. I shoo away these thoughts, and try to think only positively.

“May he enjoy nothing but happiness,” I intone. Not wanting to draw attention, I intone to myself. “Days without embarrassment. Days without pain.”

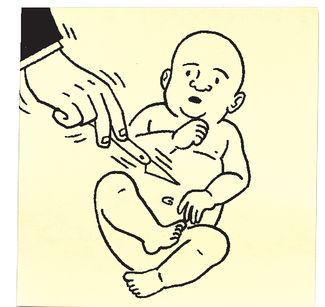

Or at least seven days without pain, at which point he will have the flesh at the end of his penis shorn off.

After which Dixie cups of schnapps and honey cake will be served.

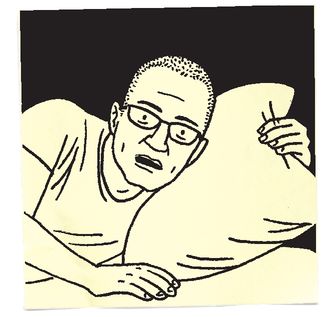

The night before Justin’s bris, I can’t sleep.

After the last bris I attended, it was days before I could pry my hands out of my pockets.

At 6:00 a.m., I decide to just get out of bed and make my way over to the synagogue.

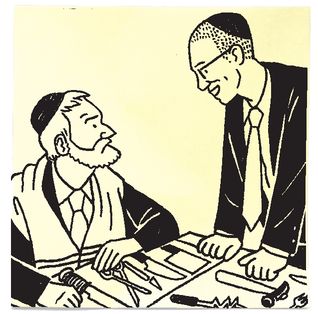

I’m the first guest to arrive, so I hang out with the mohel. As he prepares his tools, we make small talk, and at a certain point, he tells me why he got into “moheling.”

But before he can get very far, and with my heart racing because I know it might be the only time I’ll ever get the chance to use this line on an actual mohel, I blurt out, “For the tips?”

The mohel doesn’t laugh, which doesn’t make sense to me. The context is perfect, and my timing, impeccable.

I conclude that to be a good mohel, you must always be on guard against the peril of shaking with laughter.

In other cultures such sure-handed individuals might become jewel thieves.

With their steady hands they could become expert bomb deactivators.

Or even one of those guys who teaches you how to paint landscapes on TV.

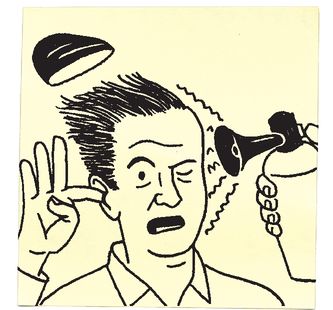

But not the Jews. If you’ve a son impervious to backfiring cars and air horns, it’s off to moheling college. Or, if you’re a little “off”—medical school.

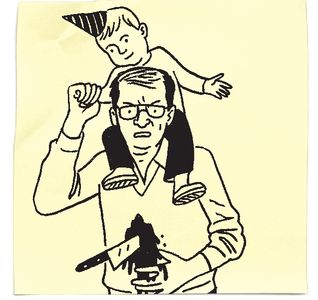

The family shows up and things begin. I have been honored with the task of holding the baby during the procedure.

I am later shown a photo of me, Justin in my arms, looking off to the side as though turning away from a horror film. Which, in fact, I am.

To keep steady, I imagine I am holding the future itself. Which, in fact, I am.

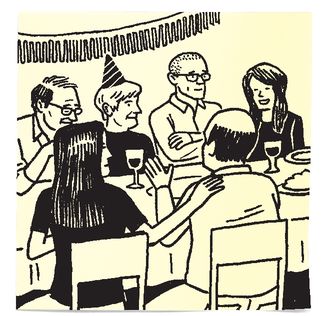

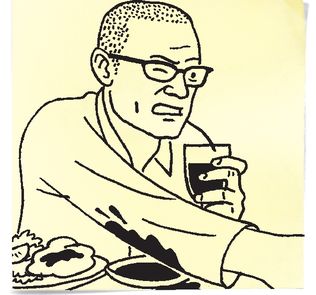

And so the future begins: Mother’s Day—Justin’s first—and when I show up to the Greek restaurant, my family is already at the table.

We focus all of our attention on Justin.

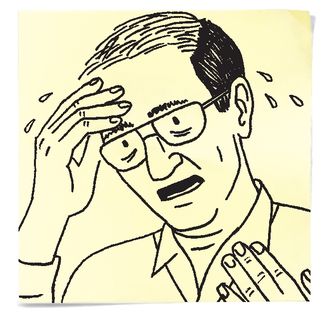

We constantly worry for his comfort and safety, and so every time he shifts in his baby seat, we clutch our hearts and mop the sweat from our brows with fistfuls of napkin.

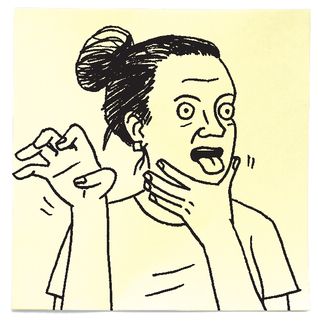

“I love him so much it hurts,” my sister says, her hand on her mouth.

“Me, too,” my father says. “It physically hurts.”

“It’s like someone is beating me with sandbags,” my mother says.

“With me it’s more of a stabbing,” my father counters.

“I love him so much,” my aunt says, “it’s like having a serrated blade corkscrewed into my side.”

Not one to be outdone, my sister weighs in: “I love him so much I feel like I’m drowning in love and can’t breathe.”

She demonstrates the sensation by making gagging and gasping noises while scratching at the air.

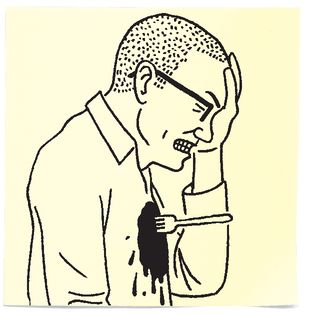

As we eat, my father accidentally tips a plate of olive oil into his lap.

Pretty soon afterward, my aunt somehow manages to drip the wax from the candelabra onto her pants.

When I look over at my mother, she is wearing a bib of smeared tzatziki sauce across the chest of her black turtleneck.

Ironically, the baby proves to be the neatest eater of us all. Truly, it feels like he is the best of us all.

I look over at him and he smiles a little smile at me that fills my heart with so much love.

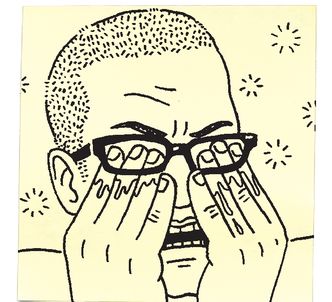

It’s as though I have had my eyes sprayed with acid.

And my heart stabbed with a salad fork.

Wincing, I reach across the table for another soothing spoonful of taramosalata, and as I do, I drag my jacket sleeve through a puddle of spilled gravy.

It feels like the final touch-up to a happy family portrait.