2

Neuropsychological Aspects of the Attentive Self

Anatomy is destiny.

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939)1

Keep your mind clear like space, but let it function like the tip of a needle.

Zen Master Seung Sahn (1927–2004)2

Only after Zen-brain relationships are oversimplified do they become easier to understand. So, we begin by weaving the threads of five simpler themes into the contents of this book: Self, attention, emotion, language, and insight. This chapter continues to address a major topic: the Self and the ways it attends to the space that surrounds it. This Self is more than an abstraction. Note the tall capital S. It is there to remind us that we have all been conditioned to protect our precious Self. Expect turbulence when any part of your cherished investment feels threatened.

The Greeks had two useful words to describe the Self’s dual aspects. Soma refers to its tangible physical representation, the body. Psyche refers to the Self’s mental or spiritual functions. We represent these somewhere in our intangible mind. We will discover that the functional anatomy of the brain also reflects this important distinction between attributes that are physical (tangible) and those that are mental (intangible): we can easily reach down to touch our knee (soma) but we cannot touch any intangible thoughts that keep popping in and out of our mind (psyche).

The Soma

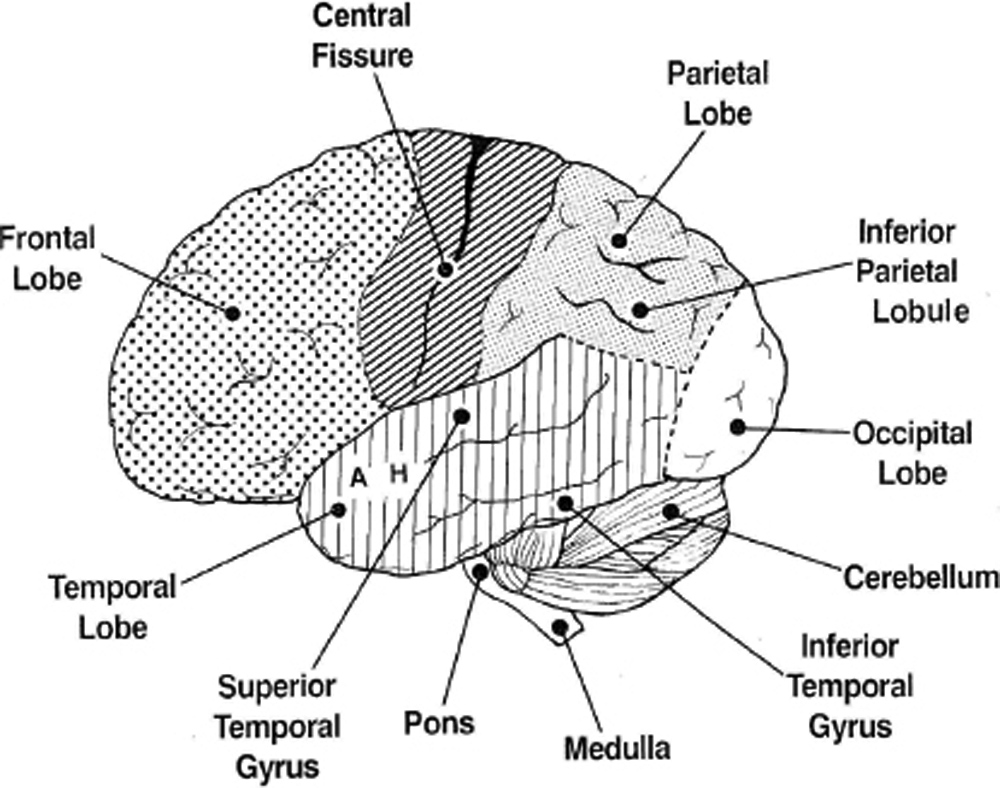

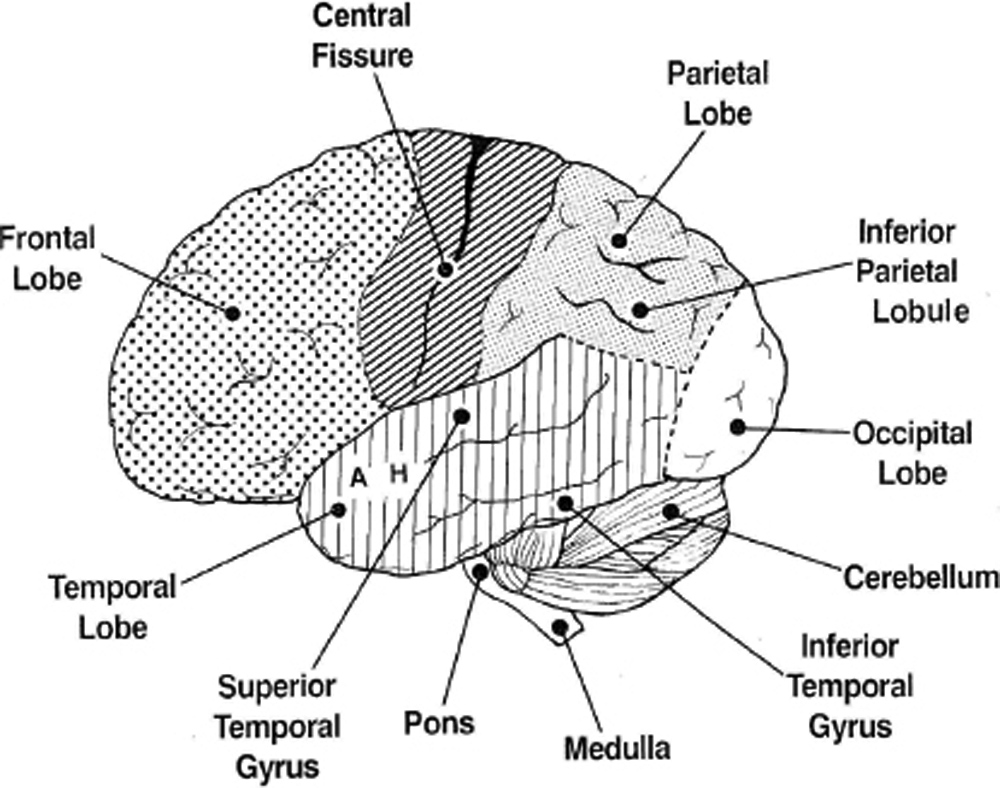

The distinctions begin anatomically: touch sensation relays up from our knee into the primary somatosensory cortex. This cortex lies behind the central fissure, in the front part of the opposite parietal lobe (please see figure 2.1). Up here, we also develop higher-order proprioceptive discriminations. These tell us where our knee is located in space. This information is further refined in the somatosensory association cortex. It is located above and just behind the primary sensory cortex. In this region of the superior parietal lobule we start to articulate all the separate sensory messages that are arriving from our hands, feet, head, and other body parts. The result is a total three-dimensional personalized construct. This unified head-and-body 3-D schema becomes the basis for our using higher-order forms of integrated behavior to engage the outside world.

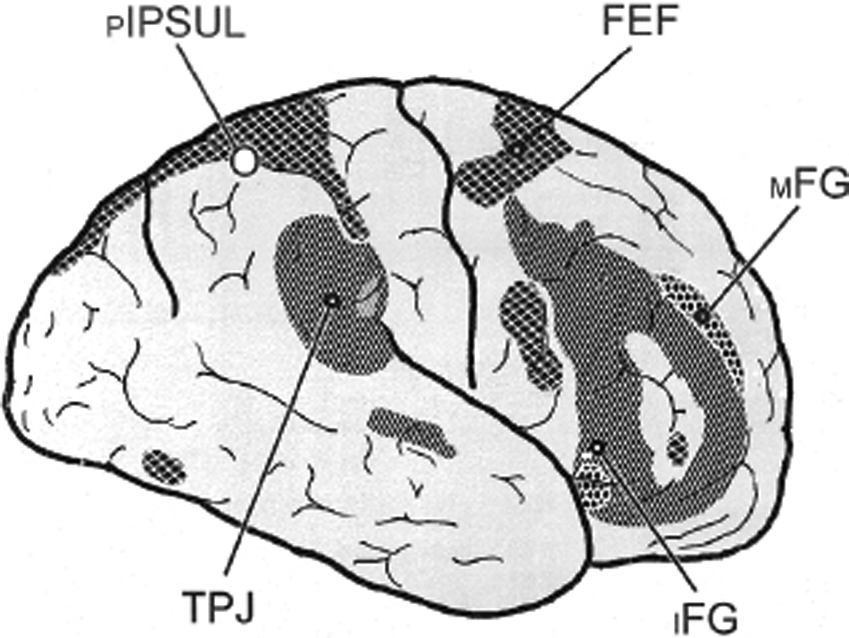

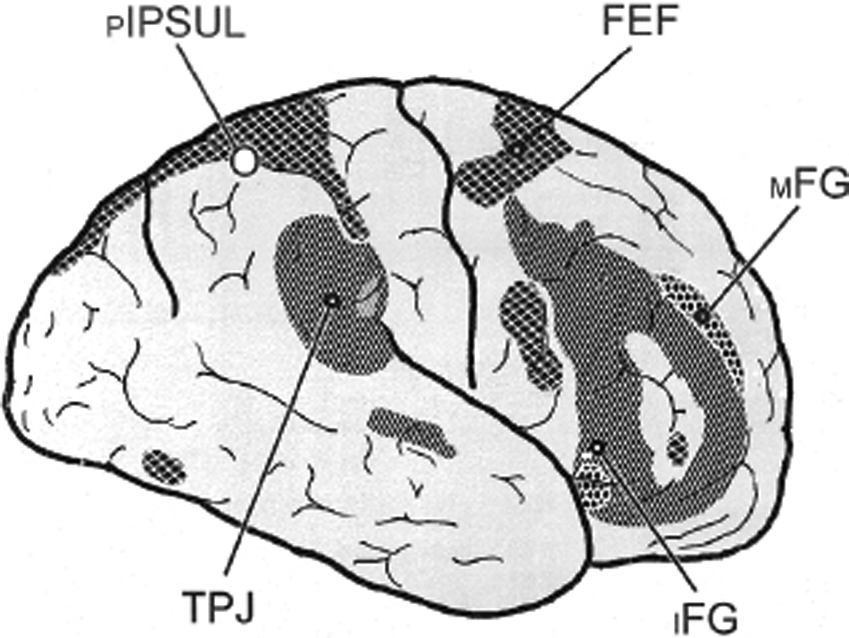

There’s more. Figure 2.2 represents the two systems of attention that arise over the outer cortex of the right hemisphere.

We can begin by asking this question about our Self’s dual systems for representing the functions of our body/mind.

• Which of these two major attention systems, because it overlaps the regions that represent the primary and secondary sensory associations of our soma, will have the most ready access to these somatic regions?

The dorsal attention system. Its two lateral frontal and parietal modules combine their capacities for directing our focal attention. One module is located back in the posterior intraparietal sulcus (pIPSUL). The other is in the frontal eye field (FEF). Their interactive functions help us focus our top-down attention efficiently, for example, when we look down to use our fingers to manipulate the touch screen of a cell phone.

Figure 2.1 A simplified version of major anatomical landmarks on the left side of the brain

At the viewer’s left is the convex surface of the frontal lobe. Just behind it is the primary motor cortex, then the central fissure, followed by the primary somatosensory cortex. Farther back within the parietal lobe, where the black dot rests, is the superior parietal lobule. This is our somatosensory association cortex. The intraparietal sulcus is the valley separating it from the cortex of the larger inferior parietal lobule beneath. The occipital lobe is at the far right. The long temporal lobe extends forward from it. The letters A and H refer to the much deeper locations of the amygdala and hippocampus. Both nuclei are hidden from sight, in the innermost (medial) portions of the temporal lobe. Below the cerebral hemisphere are the cerebellum and the brain stem. The midbrain lies above the pons, also hidden from view. Both structures contain a vital central core of gray matter, the periaqueductal gray. The spinal cord (not shown) descends from the medulla.

Figure 2.2 A lateral view of the right hemisphere depicting the dorsal and ventral attention systems

In this figure, we’re looking at the outside of the right hemisphere. Now, the right frontal lobe is positioned at the viewer’s right. The ventral (bottom-up) subdivision of the attention system is shown as gray areas composed of diagonal lines. Its chief modules are the TPJ (temporoparietal junction) and the inferior frontal gyrus (iFG).

The dorsal (top-down) attention system is shown in black checks. Its chief modules are the pIPSUL (posterior intraparietal sulcus) and the FEF (frontal eye field). The two pale dotted zones in the right inferior frontal gyrus (iFG) and middle frontal gyrus (mFG) represent regions of executive overlap. They help integrate the functions of the two subdivisions in practical ways. The results serve our global needs for attention to suddenly shift its focus to some event that might arise from anywhere in the environment—high or low, right or left, near or far.

The figure is freely adapted from figure 5 of a landmark article by M. Fox, M. Corbetta, A. Snyder, et al., Spontaneous Neuronal Activity Distinguishes Human Dorsal and Ventral Attention Systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2006; 103: 10046–10051.

Some normal people are more competent than others at sharpening the kinds of attentional skills cited in the chapter’s epigraph by Master Seung Sahn. These better performing individuals already show distinctive baseline patterns of their resting functional MRI activities.3 Their slow spontaneous patterns of fMRI connectivity predict how capable they can become when their visual attention undergoes further training.

A stringent task was used in this training experiment by Martin et al.: the subjects had to detect the symbol ⊥ when it appeared briefly down among many other distractions in the left lower quadrant of their visual field.4 [MS: 101–102, 214–215] The subjects who could detect this low target best turned out to be those who achieved a fluid blend of two sets of skills. Their versatile connectivities seemed to enable them (1) to focus on one local spot (while suppressing adjacent distracting stimuli), and (2) to detach from this excessive top-down attentional control, at least during their earliest learning trials. Our physical and mental competence depends on a similar blend of flexible, implicit skills. They tap subconscious resources. These skills enable subjects to improve their accuracy during tasks that are currently being used to train the elementary skills of perceptual learning (see chapter 14). 5

Suppose we are not subjects being tested in a lab. Suppose we are out in the real world where our task is to eat spaghetti with a fork or to sew on a small button. In what part of space do we accomplish these careful manipulations? Down within easy reach of our soma. This is our near space. It lies close in. In this domain of peripersonal 3-D space our innate parietal lobe skills of proprioception and touch operate at a premium. Each time we need to focus attention on some tangible object we hold in our hands, we are using our dorsal attention system.

But suppose we are outdoors. We are trying to identify which birds are issuing those calls we hear far off in the distance, 100 yards away. Now we require keen distant sensory skills, discriminations based on vision and hearing. To distinguish among options this far beyond reach of our hands, we must draw on temporal lobe interpretive capacities. By Freud’s era, most medical students were learning that these two lobes—the parietal (upper) and the temporal (lower)—expressed very different neurophysiological functions. Medical students still learn that the lower parts of one occipital lobe are responsible for seeing into the upper parts of space on the opposite side. Everyone needs to be reminded that these basic anatomical differences carry important implications.

The Psyche

The omni-Self of our psyche emerges from a larger matrix of networks. These are represented among many anatomical levels. That said, two major cortical regions serve the essential higher processing functions consistent with much of our personal psyche. [ZBR: 200] Notice that many of these autobiographical functions of the Self begin in networks represented along the inside surface of the brain, not on the outside regions that represent our physical body and modes of attention.

Chapter 3 discusses these regions of the psyche in greater detail. There, figure 3.1 will identify the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), in front. Farther back is a very large part of the medial posterior parietal cortex. It will serve to represent other related higher processing functions. A small personalized contribution to psychic functions is also represented in the angular gyrus out on the lateral cortex of the inferior parietal lobule.6 [SI: 53–83]

• How can this preamble of basic functional anatomy help us relate to the selfless perceptions of a sage like Bahiya?

The neural evidence indicates that we first register these bare sensory perceptions (e.g., touch, proprioception, vision, hearing) in the back half of the brain. As these impulses relay forward in the brain they become much more entangled with myriads of other associations.7 Elaborate linkages occur, both with language and with other sticky attachments. Many attachments are sponsored by the emotionalized limbic subjectivities and I-Me-Mine concepts of our Self. Without knowing it, we become conditioned. [ZB: 327–334]

In the early milliseconds, as these first sensory signals register in the back of the brain, they might seem to represent a version reasonably close to reality, or at least convey some almost mirror-like sense of objectivity. Indeed, long ago, Zen Master Dogen (1200–1253) emphasized this instantaneity, noting how immediately the moon image happens when one sees the moon reflected on the calm surface of a pond.8 [ZBR: 441–443] The longer a clear, undistracted, stable awareness attends just to these initial sensory networks that automatically register just this moon image, the more likely this first image could continue to reflect sensory reality. Yet, complications lurk in every emotional overreactivity programmed into our limbic system. Each subjective veil attached to our sensory and cognitive associations obscures and distorts this reality. We become overconditioned by habit energies that infuse our emotional history into every percept and bias every action.

This qualifying preamble of functional anatomy can help us understand something important about Bahiya. Seasoned by his many decades of mature introspection into lived experience, Bahiya’s early maladaptive emotions could gradually have ceased to reverberate at their youthful, high amplitude levels. [SI: 237–244] A sage whose emotional drives have become gentled is less easily hijacked by unwholesome urgencies of the moment.

• But can such overemotionalized attachments gradually drop off? Can our former liabilities become so deconditioned that they are much less disturbing to our field of consciousness?

Later chapters continue this important discussion. We begin to answer it here by referring to certain other slowly-developing skills. These are referable to the transformed perspectives of “a mind clear like space,” that more optimal mind to which Master Seung Sahn also pointed. What other qualities besides those identified earlier as *calmness, *clarity, and *spaciousness could also ripen over time into the mature attitudes of a sage? [ZB: 660–663] The range of qualities includes

*openness,

*receptivity,

*no-thought wordlessness,

*instant, effortless discernment.

Ripening

The asterisks identify seven important attributes that emerge in the human brain during a slow developmental process akin to the ways persimmons ripen. Humans also learn by encountering life, day by day, decade after decade. This ripening is a glacially slow process of erosion. [MS: 128–129] Only gradually do we round off our edgy maladaptive subjectivities. Only slowly do more objective percepts arrive within a calm, clear, sensitive level of enhanced awareness.

Such an ongoing awareness seems gradually to have become transformed. The impression conveyed is that the scope of clarity of our mental space appears to have expanded (see chapters 9, 10). It seems increasingly to be managed by the simplicity and stability of an increasingly competent autopilot. The result is not a spaced-out diffuseness. Instead, more practical options seem to be sponsored within a much larger volume. In addition, an easier access develops to deep instinctual levels of kindness and compassion. This allows new behavioral options to rise up spontaneously and flourish creatively (see chapters 14, 15).

In this new millennium, we sense, as did Emerson, that the ingredients of such a long-term maturing process seem almost to express the reprogrammings of a subconscious intellect. It is much more intelligent than we could ever imagine. [ZB: 622] The silent operations of this faculty are now referred to as implicit learning. [MS: 136, 148–149, 155, 171] Similar relearning components are also the fruits of mechanisms now summed up under the term neuroplasticity. Chapters in parts IV and V suggest that open, undistracted settings—the kinds that facilitate flexible creative responses in general—may also be accompanied by calmness, clarity, and the other attributes just identified with asterisks.

Maturation

Maturity implies the capacity to make wiser decisions with greater objectivity. Maturing opens up options to behave toward others in ways that express authentic selfless compassion (Sanskrit/Pali: karuna). Can such a lower-profile self ease us into more genuine relationships with other persons? It can, because it has let go of many earlier clinging attachments to its former sense of sovereignty. One prerequisite for this transformed behavior is a heightened and deepened level of global awareness. How can such an awareness look out with greater clarity into the world? Its larger perspective rests on a firm foundation: a simplified, uncluttered, unfearful attitude of mind [ZB: 641–645] (see chapter 15).

Global awareness ripens into the capacity to discern potential events as options that take place inside the larger volume of mental space. This vast space is not the ordinary impractical projection of our fervid imagination. Instead, our brain represents this mature space as a special kind of empty stage on which the play of potential events becomes instantly interpretable. Why? Because, as Seung Sahn taught, events take place in mental dimensions. Clear space and focused attention allow events to appear more meaningful as well as more discrete. [ZB: 487–492]

Maturation has a long horizon. No fixed boundary limits it to any single decade. We have every reason to think that 35-year-old Siddhartha continued to mature in wisdom on his travels during the next 44 years after that major awakening at Bodh Gaya. And at some points on his long Path, a few chosen words would guide two elderly men toward “just this.” This core insight would later become a teaching available to assist persons of any age to mature further in wisdom.

The ancient sutra phrase “just this” defines a distinctive moment of insight-wisdom. It is synonymous with other words, including “thusness,” that try to distill the essence of what enters direct experience once the maladaptive Self drops out and allocentric processing fully awakens. To D. T. Suzuki, this word was “suchness.” He viewed it as “the basis of all religious experience.” [ZB: 549–553; ZBR: 361–363, 368–369, 416–417]

Chapter 3 considers how these states of deep insight-wisdom alluded to in ancient Pali sutras and old Zen lore necessarily express a remarkable mental atmosphere. In this fresh perspective, a clear consciousness looks out into the ordinary world. Out there it discovers how extraordinary and inclusive this world really is when emptied of all maladaptive subjectivities.