4

Buddhist Botany 101

Until we can see a big Buddha in a small leaf, we need to make much more effort . . . When you see a large Buddha in a blade of grass, your joy will be something special.

Shunryu Suzuki-Roshi (1904–1971)1

The Tree of Understanding, dazzling straight and simple, sprouts by the spring called Now I Get It.

Wistawa Szymborska (1923–2012)2

Religions thrive when they find expression in metaphors and iconographic symbols. Sudden comprehensions arise in outdoor settings. Early Buddhist teachings shared a rich, earthy relationship with native trees, plants, and flowers.

A Memorable Event in the Spring

People everywhere appreciate that all life hinges on Earth’s fertility. Just as April finds us celebrating the bounty of Mother Earth on Earth Day, so was it customary long ago for people living in southern Nepal to honor their vital affinities with the Earth. How did they emphasize the ennobling virtue of hard farm work out in the field? In that era, ca. 550 B.C.E., they reserved a special day, calling on royalty for the distinction of plowing the first ceremonial furrow in the soil.3

On this memorable day, young Prince Siddhartha is attending that spring planting festival, and his own father’s hands are performing this royal plowing ritual. Left to himself, Siddhartha sits off to one side. There he chooses the cool shade afforded by a rose-apple tree to shelter himself from the heat. Mindfully attentive to each breath in and out, secluded from sensual pleasures and unwholesome states, he enters spontaneously into the first (jhana) state of meditation. After emerging from this memorable state of rapture and bliss, he then goes on to carefully examine his thoughts in solitude.

Fast forward to India, decades later. Here we find him 35 years old, exhausted and emaciated by the severe austerities involved in his six-year spiritual quest. What resources remain to him? What can he possibly do that he hasn’t already undergone? Fortunately, his long-term memory recalls that event under the rose-apple tree long ago. This was the day when he dropped into the initial state of meditative absorption. He scans subconscious levels of meta-awareness and integrates them into a key insight: This is indeed the Path to enlightenment. This remindful recollection proves crucial. At long last, he realizes how he needs to proceed.

As each narrative story unfolds in the next pages, we will often find him choosing again to sit in meditation beneath a tree. He advises his followers to do the same. Furthermore, he will follow a “Middle Way” on this later meditative Path. This approach steers clear of the two extremes, austerity and overindulgence.

Let us begin by examining the first botanical reference. It was only under a particular tree that this pivotal initiating event became so memorable in young Siddhartha’s consciousness.

The Rose-Apple Tree

This branching, broad-crowned tree (Syzygium jambos) is native to Asia.4, 5 Other than its ample shade, what else might draw a person’s attention to it in the springtime? First, its greenish-white flowers have multiple stamens. Each stamen is three inches long, so they all stick out like a bunch of spikes. Second, the tree’s narrow leaves are already a glossy red color when they begin to issue from their buds. Only after its maturing leaves make chlorophyll do they turn dark green. Later still, once the greenish-yellow fruit fully ripens, its size will finally attain two inches. Although this mature fruit now yields a fragrant bouquet, it becomes edible in preserves only after much more culinary processing. In Hawaii this rose-apple tree is called Ohia-ai. Sheltered in groves, in that climate, it grows 50 feet high and casts a long shadow.

Given the many dubious legends that have grown up around the Buddha, why can a sutra that specifies a rose-apple tree6 convey a useful message for contemporary Buddhists? We live in an era when the phrase “post-traumatic stress disorder” too often reinforces the notion that memories cause damage. That’s not the message here. This story about the rose-apple tree affirms that pivotal positive resources reside in long-term memory. Remindfulness is practical. Effortlessly scanning our whole past, it sponsors vital and affirmative insights. These insights illuminate moments all along the meditative Path. Remindfulness, operating silently, improved Siddhartha’s life, and it has the capacity to improve our lives. [MS: 94–100, 180–181]

Under a Pipal Tree

Next we take up the more familiar events in Siddhartha’s story. Now he is in northeast India, ca. 528 B.C.E. His long-term memory circuits have just reminded him of this singular link to a tree in his youthful past. Informed silently by this insight, he now understands what he must do. Which tree does he select this time? He chooses a tall pipal tree. When he sits under it, he intends to remain there in meditation until he finally becomes enlightened.

The details of what happens next may vary, yet accounts over the centuries agree that this is a person whose consciousness then underwent a total transformation.7 Having dropped off all former overconditioned layers of Self- centeredness, he awakened under this “tree of understanding.” He finally saw with deepest insight-wisdom into the non-dual nature of existential reality. The site where this epic transformation happened was thereafter called Bodh Gaya.

Ch’an master Yun-men (864–949) helped to perpetuate one potentially informative version of the story.8 This was the intriguing legend that Siddhartha, after having meditated through the night, looked up above the horizon into the eastern sky before dawn. There what captured his attention was the bright morning star, the planet Venus.9 Such a striking visual event could help trigger an awakening. Independently, in the Pali canon, the Buddha confirms the remarkable brilliance of the morning star.10 In fact, he hints that the morning star’s potent illuminating capacity is only surpassed by the way that the practice of loving-kindness itself “shines forth, bright and brilliant” to liberate one’s mind.

Some early legends suggest that he also may have reached down and “touched the earth” shortly after he became enlightened. This mudra (symbolic gesture) has become part of Buddhist iconography. It is often interpreted as though the Buddha were calling upon the Earth itself to confirm that he had “achieved” this great, liberating, awakening.11 A more humble interpretation suggests itself: the touch of one’s fingers representing a simple contact with the soil. Such a universal gesture could reflect the deep realization of someone who had become so open at that moment as to feel intimately unified within the oneness of the whole universe. In such an all-inclusive context, the ground at one’s feet could serve as the closest tangible point of direct Nepali reference. We observed that a similar down-to-earth theme was part of the Nepali custom on that earlier spring day when young Siddhartha first meditated under the rose-apple tree. Every gardener whose fingers reach into the soil in the springtime shares in the primal sense of grace conferred by this touching renewal with the elemental fertility of the earth itself.

The Buddha remained under this pipal tree for several days, integrating the profound implications of this fresh understanding into his newly transformed consciousness. As he reflected on how such a remarkable state of awakening had liberated him instantly from all prior suffering he realized what his next role in life would be: he would become a teacher, helping others learn how to relieve their suffering. This would be the Path he followed for 45 years.

The Bodhi Tree

Bodhi means “awakened” in Sanskrit and Pali. Soon the names of the tree, this man, and this place were all transformed. Originally, the pipal tree was just another member of the fig family. Thereafter, it was honored by Linnaeus with the special name Ficus religiosa (“sacred fig”). Its wide, heart-shaped leaves, reaching some 6 inches in length, narrow into a remarkably long-tailed tip. This unique tip can extend for another 2 to 3 inches. It serves as a metaphor for the heartfelt extensions of loving-kindness and compassion that reach outward toward others from the core of Buddhist practice (see figure 4.1).

The Bodhi leaf evolved into a symbol closely associated with Buddhism. (In Christianity the palm serves as a reference for the events linked with Palm Sunday.) Bodhi leaves serving this symbolic purpose illustrate the cover of an art book entitled Leaves from the Bodhi Tree.12 The presence of Bodhi leaves in this scene identifies the Buddha as the subject of this otherwise ambiguous stone sculpture carved in the eleventh century. The clues are the heart-shaped leaves with the long drip tails, covering the branch over his head.

A reasonably close relative of that original tree still exists. Its shade welcomes pilgrims who journey today to Bodh Gaya in the Indian state of Bihar. We are informed that this Bodhi tree grew from a sprout that had been transplanted from a much older tree that had been growing for centuries in Sri Lanka.13 That aged tree, in turn, is said to have been grown from a branch taken from the original, ancient Bodhi tree up north at Bodh Gaya. In the third century B.C.E., this cutting from that original tree was said to have first been rooted in a golden container, then shipped south to Sri Lanka as a gift from Ashoka, who was then the Buddhist Emperor of India. There, it flourished in a special garden in the ancient capital of Anuradhapura.14

In recent years, Bodhi tree leaves have served to illustrate the first page of the newsletter of the Honolulu Diamond Sangha, a Zen community founded by Robert Aitken-Roshi (1917–2010). The cover of Thich Nhat Hanh’s recent book Your True Home is graced by three distinctive Bodhi leaves.15

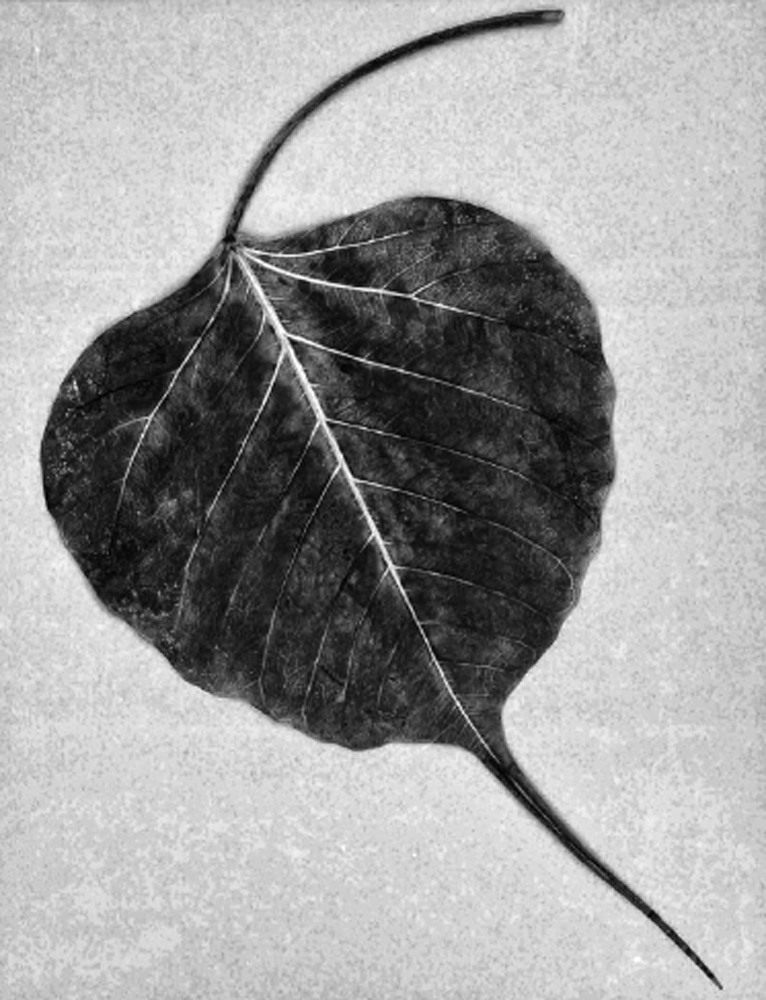

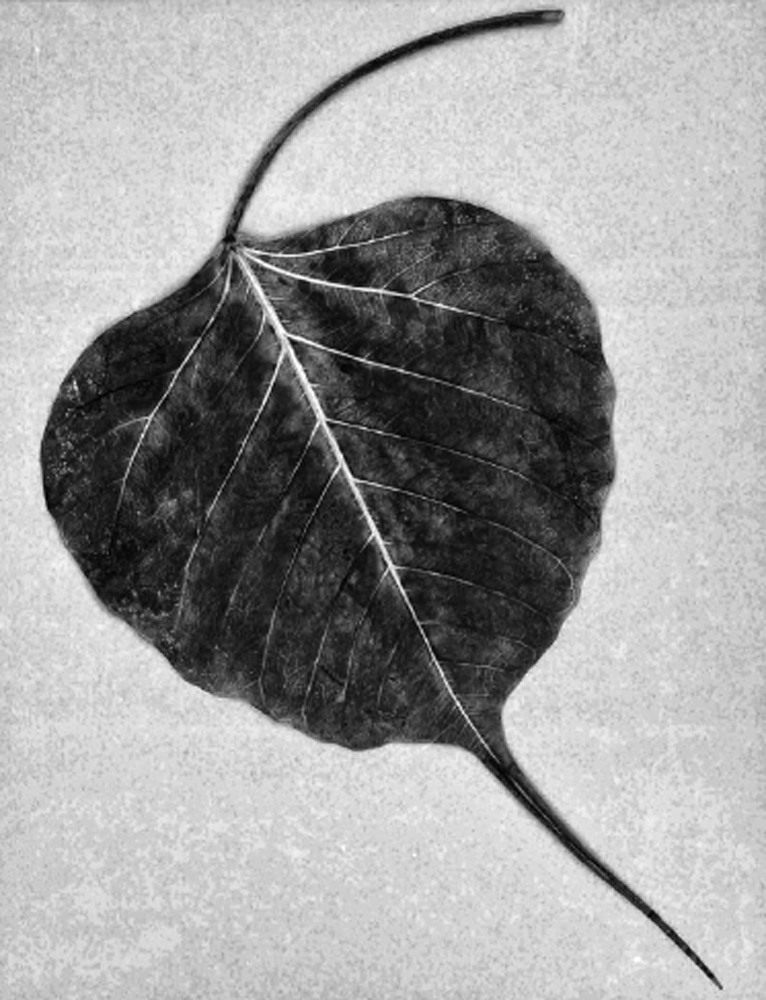

Figure 4.1 Leaf from a Bodhi tree (Ficus religiosa)

Notice the distinctive tail issuing from the bottom of this broad leaf. (This tail is 3 inches long in the original leaf). The flexibility of the long stem, which is of equal length at the top, is another feature. It distinguishes the heart-shaped Bodhi leaves from the rose-apple tree’s short stem and narrow, lance-shaped leaves.

The Lotus Plant Enters Buddhism

For millennia, the perennial lotus blossom symbolized the purity inherent in the authentic spiritual Path. It was widely understood among Hindus and then Buddhists that the special beauty of the lotus flower in full bloom remained unsullied, free from clinging attachments that originated in the muddy ooze down at the bottom of the pond. Accordingly, for aesthetic reasons, it became traditional for the early artists to portray their deities on a throne of open lotus blossoms. Beyond this ancient role in iconography, the bloom of the sacred lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) was later adopted as the National Flower of India.

The large Asian lotus flowers are colored various shades of pink in their natural aquatic setting. An intrinsic metabolic cycle prompts them to become warmer and to disperse their scent as the blossoms open up between 5 a.m. and 6 a.m. This is another reminder that Siddhartha’s awakening was said to have occurred just at the first hint of dawn. [ZB: 621]

The lotus enters Buddhist narratives in several other ways. A later sutra, called the Lotus Sutra, became emphasized in the Mahayana Buddhist tradition as it moved north to evolve in China, Korea and Japan. Most verses in the sutra are not directly attributable to sayings of the historical Buddha. They express metaphysical themes through parables that originated in India during the first century and were translated into Chinese by the year 255.16 This Lotus Sutra remains relevant for our purposes. Its name symbolizes the warmth inherent in the lotus bud as it goes into bloom and that open-hearted warmth exemplified by the key principle of authentic compassion (Sanskrit: karuna).

This ideal quality of compassion was initially embodied in the Indian bodhisattva named Avalokiteshvara. It was later venerated as Guanyin in China, and finally as Kannon or Kanzeon in Japan. This universal symbol of Buddhist compassion becomes most effective when it is closely associated with a refined degree of wisdom. How is this refinement to be expressed? In the art of detecting, discerning, and skillfully responding to each sound of the suffering that arises from the anguished world.

Meditators have a practical reason to be aware that their keen sense of hearing (audition) can play a potential role in the physiology of their own awakening. When a meditator’s hearing channels become sensitized, a sudden auditory stimulus—such as the “clack” of a pebble striking a stalk of bamboo [SI: 112–113], the “boom” of the temple drum signaling lunch time,17 or the unexpected “caw” of a crow (see chapter 6)—sometimes becomes the trigger that helps open this receptive brain into an awakened state of kensho-satori.

A Flower Is Used in the Later Teachings

D. T. Suzuki once mentioned a story that entered into Zen Buddhist teachings in later centuries.18 The Buddhist sangha on this occasion is said to have been gathered on Vulture Peak. There, the Buddha is invited to lecture at length. He says not a word. Instead, he simply holds up to the audience a single flower. It is only one of many flowers that had just been given him. His senior disciple, Kashyapa, nods and smiles softly. He alone comprehends the significance of the silent message: he will be entrusted to lead the sangha later, after the Buddha dies.

Several resonances came to be associated with this story about a single flower. The first is that the essence of the Way remains inexpressible in ordinary language. The message is that a special, subtle relationship will emerge between master and student. Only after years of working together would this wordless intuitive communication so ripen that it served to bridge their mutual understanding. The Japanese term nenge-misho refers to this wordless gesture. It is the implicit acknowledgment of merit equivalent to the transmission of the authority to teach others.19

A Handful of Simsapa Leaves

The Buddha’s effectiveness as a teacher often hinged on the way he chose other simple tangible nearby objects to illustrate his message. For example, we find the sangha dwelling on another occasion in a grove of simsapa trees.20 Picking up a mere handful of these fallen leaves, the Buddha asks the gathering, “Are there more leaves in my hand, or in the simsapa trees overhead?” They reply that the trees overhead obviously contain many more simsapa leaves. The Buddha uses this sharp contrast in numbers to make his point: he had chosen only a few teachings previously to emphasize to his followers. Why had he concentrated on these few? Because countless other teachings were not essential to the spiritual Path, nor were they “the kinds of direct knowledge which might lead to enlightenment.” Which fundamental truths did he emphasize? The Four Noble Truths: “Suffering, the origin of suffering, the cessation of suffering, and the Way leading to the cessation of suffering” (see chapter 1).

The Simsapa Tree

The simsapa tree is Dalbergia sisu. If some today still call it the Ashoka tree, they perpetuate the name of the Buddhist emperor who reigned ca. 272–ca. 236 B.C.E. and whose presence lingers in several stories herein. In India, the Dalbergia tree can grow to a height of 80 feet. Its clusters of yellowish-white flowers resemble those of pea plants and later develop into a flat pod.21

A Basket of Understanding Lined with Lotus Leaves

Elsewhere in the early Pali sutras, the Buddha reemphasizes that his disciples need to understand deeply the four ennobling truths of suffering.22 Thus, he says, “You might think it’s possible to hold on to your [intellectual] understanding of these truths before you arrive at the deeper levels of insight. However, this is like trying to hold water in a leaky basket when you’ve only constructed it out of pine needles. But later, after you’ve made this deep breakthrough, you can finally retain your comprehension of the truths of suffering. Now your basket of understanding resembles one made out of broad, sturdy, lotus leaves that will finally hold water.”

The Lotus Leaf

Lotus leaves have an unusually waxy, microtextured surface.23 The leaves’ extraordinary ability to shed water is now described by a special term, the lotus effect. In a pond outdoors, drops of water keep rolling off lotus leaves. This useful hydrophobic property helps explain why the Buddha would have selected lotus leaves to line the inside of a water-retaining vessel. This self-cleaning action helps the plant wash off harmful insects, spores, and toxic substances that might cling to an ordinary leaf. The lotus leaf metaphor becomes of further interest to Buddhist meditators in every era who hope to shed their own pejorative clinging attachments.

Leaves Entering Other Teachings

It is a cold February morning. The Buddha and his disciples have been staying in yet another forest of deciduous simsapa trees. The Buddha is sitting at rest on a thin layer of simsapa leaves that had fallen to the ground.24 Young Hatthaka is walking by. Seeing the Buddha, he stops, comments on how hard the ground is and expresses the hope that the Buddha had slept at ease even though his thin garment would not have protected him from the cold winter wind.

“Yes,” says the Buddha, “I am one of those who does sleep in ease. And now in return, let me ask you, young man: Suppose a well-off homeowner—or his son—were each to own well-insulated homes, have a warm bed, and have wives to attend to them. Will these men necessarily sleep in ease?” “Yes,” says the youth. But the Buddha continues: “Suppose each of them were also burning with the emotions of longing, or those of loathing, or their minds were consumed by the fires of delusions. Under these conditions, would they then sleep miserably?” “Yes,” is the reply. “Well,” says the Buddha, “to be enlightened is to be spared from each of these three afflictions. The person who has abandoned these unwholesome passions and delusions can sleep in ease.”

The Buddha acknowledged that he was only the most recent of countless other enlightened teachers who had preceded him. In this context, he is reminded of an earlier religious teacher by the name of Araka.25 How had Araka introduced the important principle of impermanence to his hundreds of disciples? By continuing to remind them: “Human life is short, limited, brief, full of suffering and tribulation. One should understand this thoroughly, lead a pure life, do good things. Just as a dew drop vanishes from a blade of grass as soon as the sun rises, so too is each human life like this dew drop—short, limited, full of suffering and tribulation.”

Later, in Japan, Zen Master Dogen (1200–1253) elaborated on the image of a drop of dew on a blade of grass. In the first chapter of his major work, he observed that one single drop of dew on this leaf of grass still suffices to reflect the full moon and the entire sky.26

The Buddha Meditating Under the Banyan Tree

On another occasion after he became enlightened, we discover the Buddha again meditating at the base of a tree. This time, he has chosen a banyan tree.27 Sitting erect, in the full lotus position and in deep meditation, he is an imposing presence. Dona, a Brahmin passerby, is struck by the nobility of his appearance. Somehow, having just glanced at this meditator’s footprints in the dust, he is under the impression that these imprints display rare characteristics of the kind that he associates with divinity. So, in his next probing questions, he seeks to place the Buddha at one particular level in either the holy or the human pantheon.

To each such question the Buddha responds, “No.” Instead, he uses a botanical reference that may now have a more familiar ring. These words describe the nature of his present state as resembling that of a mature person who now lives unsullied by the world. This state is “like a lotus bloom that rises up out of the water, unstained.” He concludes by saying simply, “Think of me as ‘awakened.’” In any era, a salient characteristic of being awakened to the world is being liberated from the bondage of one’s Self-centeredness.

The Banyan Tree

The banyan tree, Ficus benghalensis, has many remarkable characteristics. These led to its being recognized as the National Tree of India. One of the longest-lived and largest trees, the banyan has numerous aerial roots that reach down into the soil from its low-spreading branches. These roots not only supply nourishment. They also form secondary trunks that help anchor the tree into the earth. In these respects, a big old banyan tree is reminiscent of the ways that Buddhism’s different branches are still extending themselves, century after century, to become grounded in the cultural soil of many lands.

The Buddha’s Explicit Advice about Places to Meditate

The Buddha was a monk who lived in the forests and served as an exemplar for his followers. He not only meditated at the base of a pipal tree or banyan tree, he gathered his community in groves of simsapa trees. In still another forest, how did he advise his disciples to avoid the hazards of sensuality? He suggested that they go into a solitary retreat in the wilderness and practice meditation either at the base of a tree or in an empty dwelling.28

Induced Visions Including Ashoka Trees

The Lankavatara Sutra is another sutra that originated in later centuries.29 Its words invite readers to visualize an imaginary setting: a Buddhist audience said to have gathered on the peaks of Sri Lanka. Up here, when a man called Mahamati requests a teaching, the Buddha allegedly conjures up many beautiful scenes. These images become visible and are shared by everyone in the assembly. In this scenery, groves of Ashoka trees and other forest trees now glisten in the sunlight. Then, having created this imaginary setting, the Buddha suddenly causes everyone’s visionary scenes to vanish! Why? The Buddha then explains the basis of this teaching: all of our perceptions—like these transitory visions—are only projections of our own mind. Don’t cling to them. They don’t last. The message is, Don’t stay attached to what your imagination happens to perceive (nor cling to doctrinaire interpretations of the Dharma). Instead, realize that the essence of the spiritual Path resides neither in abstract words nor in metaphysical visions. Where, instead, is truth to be realized and authenticated? Within the depths of your own direct, insightful daily experiences.30

The Buddha’s Final Teaching

Knowing that he was dying, the Buddha selected his final place of rest. It was in the space between two sal trees, in a forest near Kusinara.31 There, the essence of his final words to his followers was simple: “All things are impermanent. Make diligent efforts to become liberated.”32 The sal tree is Shorea robusta. It is a tree native to East India, noted for its yield of close-grained, hardwood timber and large, broad leaves.

In Summary

These landmarks in early Buddhist history are reminders that we are part of Nature. The early teaching stories were often grounded in the simplest botanical references to particular trees, leaves, flowers, or a single blade of grass. These living plants also have DNA. They co-arise from the stardust in the universe, just as we humans do. They too undergo cycles of birth and death.

Consider how many fundamental topics have just been reviewed:

* the pivotal affirmative role of remindfulness,

* our intimate changing, seasonal relationship with the generative powers of the Earth,

* awakenings that arise like the lotus in full bloom, unsullied by any attachment to their earlier muddy origins,

* the refinements of insight-wisdom that ultimately help generate the warmth of authentic compassion,

* the vital role of states of deep insight that enable one to retain one’s comprehension of the Four Noble Truths of Suffering,

* a subtle allusion to shedding superficial clinging attachments,

* the total release from a life of suffering that arrives after one has finally extinguished the three lingering fires of greed, hatred, and delusion,

* the base of a tree as a place to meditate in solitude,

* the transient nature of the Self and its mental projections,

* the key roles of direct authentic experience and diligent practice.

Botanical resonances serve to remind generations of Buddhist seekers how they, too, can grow: by staying in touch with their own deep affinities with trees and plants that are rooted in the earth. This earth is the place where each fallen leaf serves finally to replenish the soil, where each dewdrop that evaporates from a blade of grass rises up to rejoin the clouds.