Part IV

Looking Out into the Distance above the Horizon

Questioner: Why do you always look up while you’re playing the horn?

Louis (Satchmo) Armstrong: I don’t know what I’m looking for, but I always find it.

11

Reprocessing Emotionally Traumatic Imagery While Elevating the Gaze

I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help.

Old Testament, Psalm 121 (King James Version)

The treble clef signifies the upper registers of a musical score. This chapter also involves looking up, this time into our superior visual fields. It begins with a story about two adult women. At a young age, each had undergone a major episode of emotional trauma. Later, as a mature adult, each woman in her own unique way stumbled into an empirical approach, one that would dissolve the emotional distress attached to her earlier traumatic event. First she revisualized this old disturbing memory. Then she projected the scene up toward her superior visual fields and out into the distance.

This pair of observations suggests a novel, testable working hypothesis: by elevating the line of sight and revisualizing the event above the horizon, networks representing these upper visual fields out there are enabled to access other reprocessing mechanisms that have the potential to relieve early, major psychic trauma.

This narrative has a fourfold purpose: (1) to specify how each subject proceeds to revisualize and reprocess in her upper visual fields, (2) to review recent research suggesting mechanisms that could help relieve various degrees of emotional trauma, (3) to stimulate investigators to critically evaluate this empirical approach in a larger, diverse patient population, and (4) to place elevations of gaze in a larger context that includes meditative practice, intuition, and creativity.

Background

This chapter began unexpectedly in 2010. It evolved during a training conference for chaplains at the Upaya Zen Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico. As one of the lecturers, I was describing the two ways that meditation techniques train our attention (see chapter 3). To illustrate how these differ physiologically, I projected and discussed the slide version of color plate 1 (see also figure 11.1). The caption explains how our top-down attention proceeds in an executive manner, an approach that is often deliberately focused and requires effort. In contrast, the bottom-up approach engages awareness effortlessly in a more reflexive, global manner. The neural basis of these distinctions is well established.1, 2

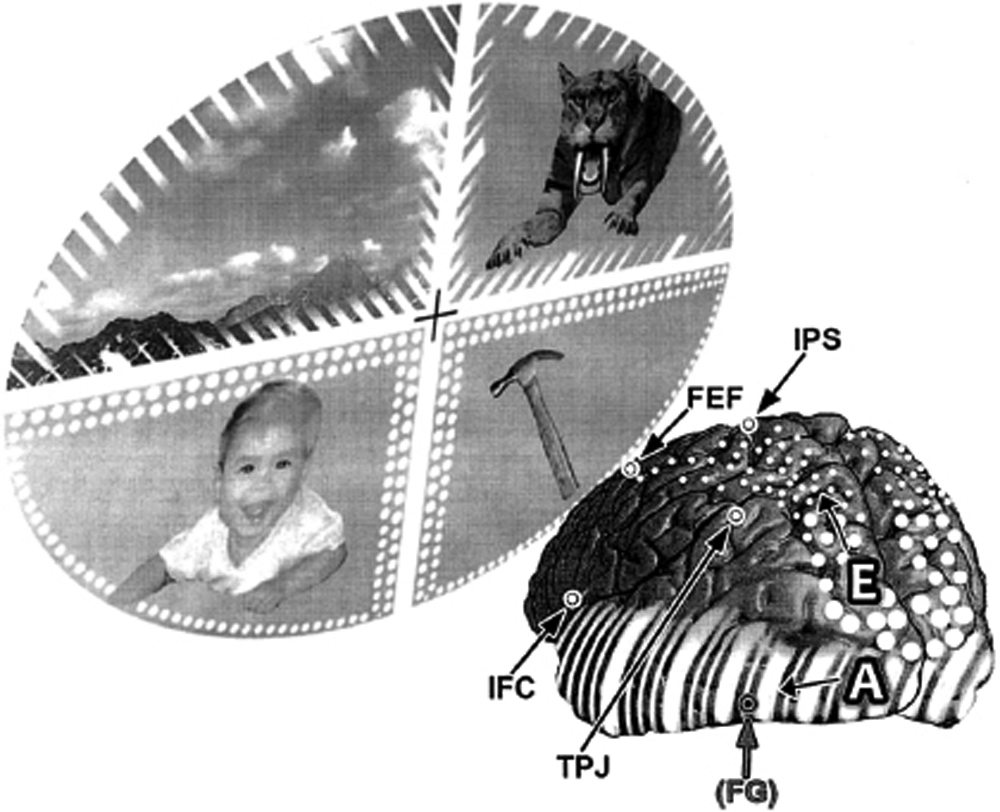

Figure 11.1 Egocentric and allocentric attentive processing; major differences in their efficiencies. (See also color plate 1).

This view contrasts our dorsal egocentric, top-down networks with those other networks representing our ventral allocentric, bottom-up pathways. Your vantage point is from a position behind the left hemisphere, looking at the lower end of the occipital lobes.

This person’s brain is shown gazing up and off to the left into quadrants of scenery. The items here are imaginary. The baby and the hammer are in the space down close to the person. The scenery above and the tiger are off at a distance.

Starting at the top of the brain are the two cortical modules of the top-down attention system: the intraparietal sulcus (IPS) and the frontal eye field (FEF). They serve as the attentive vanguards for our subsequent sensory processing and goal-oriented executive behavior. Notice how they are overlapped by the upward trajectory of the upper parietal → frontal egocentric (E) system. It is shown as an arc composed of white circles. Notice that rows of similar white circles also surround the lower visual quadrants containing the baby (at left) and the hammer (at right). Why? To indicate that this dorsal, “northern” attention system could attend more efficiently—on a shorter path with a lesser wiring cost—to these lower visual quadrants. This enables our parietal lobe senses of touch and proprioception to handle easily such important items down close to our own body.

In contrast, our two other modules for cortical attention reside lower down, also over the outside of the brain. They are the temporo-parietal junction (TPJ) and the regions of the inferior frontal cortex (IFC). During bottom-up attention, we activate these modules of the ventral attention system, chiefly on the right side of the brain. They can engage relatively easily the networks of allocentric processing nearby (A). The diagonal white lines that represent these lower temporal → frontal networks is also seen to surround the upper visual fields. Why?

This is to suggest the ways this lower (“southern”) pathway is poised globally to use its specialized pattern recognition systems. These are based on our senses of vision and audition. Each serves to identify items off at a distance away from our body and to infuse them with meaningful interpretations. The FG in parenthesis points to this pathway’s inclusion of the left fusiform gyrus. This region, hidden on the undersurface of the temporal lobe, contributes to complex visual associations, including our sense of colors.

This same color slide also illustrated two important practical outcomes:

* We express an inherently Self-centered bias when we use our upper occipital → parietal → frontal pathways. These help us focus on things close to our own bodies—the baby and the hammer. Messages that flow along this so-called “Where?” pathway pursue a dorsal trajectory. This pathway has links with our superior parietal lobule. We represent our body schema here. The overlappings between this somatosensory association cortex and our dorsal attention system are very important. They enable us to reach out efficiently to grasp things in nearby space. Therefore, the programs coded among these upper, “northern” networks are poised to do much more than simply ask “Where?” In fact, their circuits help us solve a most urgent spatial question: “Where is this thing in relation to Me and My body?” Notice how much our physical sense of Self-centeredness is implicit along this upper frame of reference.

* A second, very different category of cognitive functions exists. Notice that it begins anonymously along the lower pathways of attentive processing. This is the so-called “What is it?” route. It starts farther down in the ventral occipital → temporal region. Thereafter, the trajectory of this “southern” stream extends forward through the temporal lobe and into the inferior frontal cortex. Along this lower pathway, many interactive functions express an outward-looking, allocentric frame of reference. These are coded for “other” efficiencies. They begin with an early orientation toward recognizing objects that might present themselves (1) in the superior visual fields, and (2) out there, farther from our body. The distant scenery and the ancient predator are the examples shown in figure 11.1. Noteworthy in this regard are special semantic skills. These arise nearby among the temporal lobe’s networks of associations. These adjacent skill sets do more than help this lower processing stream identify objects. They also help this pathway imbue with meaning what it sees and hears. This semantic pathway not only asks, “What is it?” It also asks, urgently, “What does it mean?”

At this conference the next day, an experienced clinical psychologist lectured on ways to reduce the stressful impact of psychic trauma. During the discussion period that followed her presentation, she added a personal story. Why? Because it illustrated how suddenly and completely she herself had once been relieved—while in a classroom seven years earlier—of her major fear. This fear had haunted her since her teenage years.

Her vignette (in the next section) prompted further questions and comments from me, especially in view of the points that were illustrated with the slide and discussed the day before. What was special about the particular spatial context in which her emotional relief had occurred? Why was she suddenly relieved while she was reprocessing this old traumatic scene above her usual eye level and in the domain of her upper visual fields?

An audience member had witnessed each of our presentations and each of the open discussions that followed. She became intrigued. On her own initiative, she came to this decision: she would project—into her upper visual fields—her most emotionally traumatic event. This episode of intense fear had deeply troubled her since she was a child. Encouraged by her empirical results, she then sought me out. This led to her becoming the subject of the second case report.

I interviewed each person separately during this conference. Each subject was contacted by telephone several times subsequently, submitted a typewritten narrative report, reviewed her condensed report, and gave written permission for its publication. (Their initials are changed.)

Case Report 1

K.K. is a 57-year-old Ph.D. clinical psychologist who has an active private practice. Her extensive professional experience has been sought during major national and international disasters. In this role, she has helped patients and caregivers cope with stress following severe physical and mental trauma. This narrative begins by describing what she had experienced during the revisualization in that class seven years earlier.

In 2003 she was taking a training course in a biologically based approach to relieving psychological trauma. She had volunteered to be the subject for an in-class demonstration. She took a seat in front of the class. There she sat, facing the woman who was her teacher. The setting felt comfortable and safe. When the teacher invited her to revisualize one major traumatic episode, she chose the dramatic event that happened when she was 14 years old.

She revisualized her mother standing in front of her.

“My mother and her husband were having a fight. One of them held a knife and it had sliced the other person’s hand. I can’t remember who cut whom. All I can see in my images of this scene is the bleeding hand.

“The teacher then asked me to broaden my view beyond the bleeding hand. As I gazed into this scene in the kitchen, I saw the window in the background above the kitchen sink.”

During this next phase of her revisualized narrative, she gazed up and out through this 3-foot by 4-foot window. “It was night, and there were stars outside in the sky. I looked out the window and had the sense of being connected to the universe in a way that made all the emotions linked with this scene in the kitchen much less frightening, even insignificant . . . a sense of calm washed over me.”

During this unusually calming wave of consciousness, and while feeling “this connection to the vaster world outside the kitchen window,” she also remained distantly aware that she was describing the event in front of the class. But something crucial had happened: she was immediately relieved from all fear. Before this moment in class, “I could not go to bed at night if a knife was in the dish drainer.” After that classroom session seven years ago—after her awareness shifted up beyond the bleeding hand and out through the window—“I no longer had that fear.”

Notice a distinction: she did not deliberately intend to look up in class in order to gaze out through that kitchen window. This happened. In the remote past, she had been only vaguely aware that a suggestible subject who made a willfully strained effort to substantially elevate the gaze might enter into a trance. However, she excluded deliberate straining as an explanation for any of the events that had unfolded spontaneously after her revisualization of the event back in the kitchen became elevated beyond the bleeding hand.

Case Report 2

O.R. is a 57-year-old former school system secretary. She was enrolled in this 2010 Upaya conference. It was her idea to test the process of deliberately gazing up and out. The first major traumatic event she chose to revisualize was an episode of fear. This fear had haunted her since she was 11 years old.

The First Observation

The first revisualization she selected was the dramatic nighttime episode when her stepfather tried to molest her. They were alone in the front seat of his car. He had stopped the car on a bridge. She remembers being “deathly afraid” of falling off the bridge and down into the canal 60 feet below. She was strong enough to wrestle him away from her. Among her traumatic emotions was the feeling that her mother had abandoned her by not protecting her from his advances.

She chose the word retrieval to summarize the mental processing steps involved in recalling and revisualizing this traumatic episode. First, she deliberately raised her chin up in order to elevate her line of sight above her usual visual horizon. Next, she imagined herself back inside the car in that scene of intimate conflict. She then “proceeded to look past him, out the driver’s side window, and up at the distant trees. The trees appeared soft and shimmery in the moonlight. They were a hundred yards or so away, off to my right and twenty to thirty feet above where I was looking.” Though the moon itself was blocked by the car roof, “it was a bright moon, and it lighted the treetops. Looking up at the trees, there was simply a feeling of peace.”

“When I looked back then into the car, or do so now, the scene is simply an image. The pain, the fear, the feeling of abandonment is softened. I see that he is just an ignorant man, raised by a child molester himself, and simply a product of his childhood. The fear is gone; I have escaped, now, by way of the trees. I can’t be hurt from this point on. My mother, too, is forgiven. She has not abandoned me to this result; she is simply who she is, trying to survive in her own little world. Using this technique, I have since returned to this image many times. It remains soft and inconsequential. I have been growing up. It’s over. I can let it go. It’s not hard-wired anymore. It’s no longer a lump in my throat, but a warmth and forgiveness.”

Subsequent Observations That Day at the Conference

Twenty minutes later, encouraged by the success of this first experiment, she decided to test this new technique on another kind of emotional episode that remained deeply disturbing. Major feelings of green-eyed jealousy, not fear, had led to its deep, intense, ongoing emotional discomfort. This traumatic incident had occurred when she was an adult. It happened during a wedding reception. At this time, her “significant other” (now her husband) was describing to her how he had been flirting with an attractive young unmarried woman wearing a black dress. Once again, she gazed up while she retrieved this scene and reimaged it high up at an angle toward the line “where the wall joins the ceiling.”

“I took my feelings of shame and embarrassment up to that line, allowed their power to push and disseminate in that area.” The next dynamic process of revisualization lifted her man up by his shirt to the level of this ceiling and then projected him out through the French doors at the end of the hall. From there, the retrieval process tossed him up into space and “far out into the sun.” At this point, a substantial softening dissolved the intense jealousy attached to the earlier scene. Reviewing this episode subsequently, she found all earlier “shame and embarrassment” had also vanished. It “feels more like the memory of a bad party, but is no longer personal. Looking back on the scene now, I see the young woman as simply who and where she is in her life—single, without a man, when mine looked good and was promoting himself to her.”

Later Observations

Back home, after this 2010 conference ended, she applied the technique successfully a week later to relieve a second major instance of jealousy. She had felt this emotion intensely ever since a separate episode in 2006, after she and her partner were married. During a dance, her husband was on the sidelines. He was obviously enjoying the dancing movements of a different woman in a black dress, and she was also reciprocating his attention. During this retrieval, she projected both her husband and this new dancing lady out the door of the dance area, down a long hall, out through the lobby area in back, into the parking lot, and then “up into the blue sky of late afternoon.” At this point, the revisualization now “veered to the right, toward the light of the sun, and I just let them go.”

During this dispersal up into the sky, no hand of hers is the actual lifting agency. Instead, the two persons are somehow “magically retrieved by the front of their shirt and dress,” then raised toward the ceiling and out the door up into the sky. “I let them go there. It gives me pleasure and more relief and a deeper fading of the details when I retrieve the image and take it outside and into the sky. Usually, taking it outside and up is BEST.”

To project her visual imagery down below the horizontal “had never been part of my approach—they would hit the pavement.” Yet, she did project her imagery to a slightly lower site above the horizon during a fourth experiment. On this occasion, reported six months later in a letter, her objective was to relieve strong negative feelings of resentment toward two persons who had earlier jeopardized her relationship with her husband. In this instance, she first gazed up at an angle of only 5 degrees above the horizon. She then revisualized the couple as standing a long distance away from her “in an ice field in Northern Europe (an image new to me, and never seen before). I walked them out on the ice, up an incline to an elevation some 300 yards away, where their feet seemed only about at my chest level . . . Then I simply asked them to go. At this point, I felt a lifting of the hurt they had caused. I can now sit in the same room with them and not feel pain.”

Using this technique of elevating her line of sight while reimaging and reprocessing up and out, O.R. has markedly softened and dissolved the emotional distress linked with each of her years-old episodes of deep-seated fear, jealousy, and resentment. Notice, as in case report 1, that all four emotionally distressing events were retrieved out of very long-term memory. Each abrupt release from this range of emotionally traumatic events had occurred after she had first been ruminating over them for years.

Current, Less Traumatic Incidents Require an Interval of Cooling

O.R. then identified, by herself, an important temporal limitation in the effectiveness of this technique. Back home, again after the conference, she recounted a less stressful emotional experience. Shortly after the latest heated argument with her 19-year-old daughter, she went off by herself, retrieved the image of this fresh incident, and again looked up toward the ceiling. This time her revisualization “did NOT work. I was still angry and hurt. Things still felt too hot. The episode had to cool before I could put it into storage.” Then, after things had time to cool overnight, her next morning’s revisualization proved effective. Subsequently, this prior, ongoing troubling relationship with her daughter became softened. “Now I can stand outside the fray, a little easier. I’m still a Mom. I still worry and hurt for her, but I know that relief from these arguments is possible.” This episode suggests that reprocessing emotionally traumatic imagery while elevating the gaze is not effective until after the acute emotional incident has cooled. The duration of such requisite cooling periods remains to be determined.

Reviewing Salient Details of These Revisualizations

• The basic operational mode is gazing up and out in a gentle manner. No repetitive eye movements enter into these gently sustained revisualizations.

• The reimaged scene begins, as did the original trauma, with visual details inside the space near the subject. Events shift during the next phase. Now the revisualized scene is registered at elevations above the usual eye level, off at a distance far beyond this earlier envelope of close, threatening, immediate peripersonal space.

• The primary emotional incident is now reprocessed in a new spatial perspective above the usual visual horizon. It is accessing events referable chiefly within the space occupied by the subjects’ prior superior visual fields.

• Older traumatic memories can undergo a substantial emotional release when projected out and reprocessed into the distant sky. This can be a nighttime sky or a daytime sky, sunny or ice-cold.

• The revisualization experience in case report 1 developed its own momentum involuntarily. This occurred after K.K. was invited to broaden her field of vision. This next phase evolved spontaneously. It swept her awareness upward, out through the window, and into the starry sky beyond.

• Subject O.R. begins her several upward and outward revisualizations more intentionally. Her introductory phase involves deliberate top-down attentive processing. This continues in an upward direction toward elevations some 30 to 45 degrees above her usual visual horizon. The next reprocessings reflect her freedom to liberate dynamic, creative imagery at long distances.

• In retrospect, O.R. regards her abrupt releases from major degrees of long-sustained emotional distress as resembling the kinds of “growing up” insights involved in natural maturation.

• While an acute, emotionally stressful incident remains hot, it requires a cooling-off interval for the technique to be effective.

Psychophysiological Considerations

The author is a skeptical clinician. Like the reader, my first inclination might easily have been to dismiss such reports as anecdotal and empirical. However, the subjects’ substantial verbal, behavioral, and written documentation verifies that each of their most deep-seated fears was relieved suddenly and thoroughly. Moreover, by way of explanation, a review of the literature identifies seven relevant lines of research. These converge in support of a novel working hypothesis: Traumatic memories have some potential to be relieved when the sensorimotor act of gaze has access to the mental reprocessing space represented above and beyond one’s usual visual horizon.

1. Psychological Dimensions of Perception in Superior Space and Distant Space

Our dominant mode of top-down attention is Self-centered. Where do we routinely point most of our visual fixation? We direct it toward one small central spot of concentrated fine-grained focusing. Yet, the whole of ambient space also supplies a wealth of important information. [ZB: 487-495] Space was so important a topic to William James that he devoted 148 pages to the chapter on space in his classic textbook on psychology, more pages than to any other subject.3 Notice the special feeling we have about this envelope of space close to our own body. It is “our turf.” We “own” it. We guard it from others. A beneficial anonymity develops when we let go of all the maladaptive conditioning that causes us to cling so hard to this peri-personal space that we must protect it as “Mine.”

Suppose we gently gaze upward. What happens? It helps reorient other attentional resources. Where? Toward an elevated domain of more objective, impersonal processing. Figure 11.1 illustrates that when the viewer’s mental space opens up and becomes elevated into the distance out there, it may also access more readily its lower, most objective, allocentric (other-centered) resources of attentive processing. It is a short distance between the inferior occipital gyrus and the nearby lower temporal cortex. Evolutionary neurobiologists refer to such shorter paths as involving a lesser wiring cost. Discussions elsewhere amplify the potential benefits that evolve during this gazing up and out into the distance.4 [MS: 20–37, 72–91]

It makes a big difference how and where we access space. Crucial functions of the psyche become enhanced when one’s perceptions of space expand superiorally. Myers- Levy and Zhu found that normal subjects could develop positive changes in their subsequent mental processing by becoming subliminally aware that a greater vertical expanse of space existed above their eye level.5 Subjects who were in a high-ceilinged room generated more thoughts related to freedom and greater degrees of abstract ideation. They could also retrieve, spontaneously from memory, more items seen earlier without needing to be cued. The review of “grounded cognition” by Barsalou explains how changes in the basic ways people represent their sensorimotor information can create similar positive changes. These benefit their ongoing mental attitudes and interpretations.6

Normal subjects of all ages respond more creatively when their tasks are portrayed as originating at far distant, not proximal, locations. When people imagine that events are occurring at distances that are suggested to be faraway, test results show that their creativity becomes enhanced. This increased creativity has been demonstrated both in university students7 and in elementary school children.8

Suppose that the artificial test stimuli are fine-grained targets. In this instance, researchers assign tasks only in the foveal center of the subjects’ visual fields, say, at locations a mere 4 degrees up or 4 degrees down from eye level. Then normal subjects perform less well in their upper visual fields than in their lower visual fields.9 However, these subjects are being challenged to perform a top-down task while they are sitting a mere 57 centimeters (22 inches) away from the TV screen. In contrast, K.K. and O.R. were generating long-distance perspectives in space under field conditions. The degrees of elevation that they projected in their mind’s eye extended far beyond their usual horizon, way up into the distant sky.

An important step in studying this elevated visual dimension is the recent report by Bayle et al.10 They point to an “adaptive advantage” that exists out in the periphery of our visual field, not in the center. This enables the larger nerve cells in our visual systems to react instantly when a threatening event occurs in the environment. In their behavioral study, 20 adults had only 140 milliseconds to glimpse pictures of emotional faces. Notice where these subjects were glimpsing the test faces: at eccentricities up to 40 degrees above the usual visual horizon. As anticipated, the subjects reacted more efficiently to a face expressing fear than to a face expressing disgust.

Behavioral studies show that fear-producing images influence both how we originally perceive visual word images and how we later recall them into revisualizations.11 When centrally located items are transmitted only in the form of fine-grained visual details, they can interfere with a variety of later processing steps. On the other hand, the transmission of coarse-grain visual details carries some potential to enhance these later processing steps.

2. The Lability of Memories

Research in forensic psychology reminds us that the accuracy of our memories and of so-called eye-witness reports is unstable at best. Memory-linked associations undergo reconstruction while they are in the process of being retrieved. This inherent lability of episodic and semantic memories opens up important possibilities: memories can not only be modified in their factual content, but they can also drop off some old attached emotions in the act of being recalled.12 Indeed, it was when subjects K.K. and O.R. had projected their earlier traumatic imagery up into the far distant sky scape that they abruptly dropped off the major negative emotional attachments linked to these older fearful memories. The Buddha specified that a wide variety of emotional attachments could cause us to suffer, not only fear.

3. Recent Event-Related Potential Studies (ERP)

Wu and colleagues conducted an important visual ERP study.13 They measured the sequences of events that unfolded along the dorsal occipito → parietal system. [ZBR: 159, 185, 190–192] They further distinguished those event-related reaction potentials of this “northern” system from the more global reactivities that were arising farther down in the ventral occipito → temporal “What?” system. During the first 148 milliseconds of preattentive processing, their subjects’ bare spatial awareness was still openly dispersed throughout its larger field. Even so, the innate capacities of this global, “southern” system could already bundle and discern the essentials (gist) of relatively complex facial features. How sensitive was this ventral system’s early ERP peak? It arrived some 80-162 milliseconds before the focal attention of its “northern” counterpart’s system brought its top-down, feature-binding skills into conscious awareness.

Psychological conflicts can be resolved. They disappear sooner if researchers supply positive external visual or auditory stimuli that can defuse an already anxious situation. Once these resources are introduced, the subjects show appropriate changes in their earlier ERP configurations.14 This objective evidence confirms a link between positive resources and the relief of emotional stress. The ERP findings could become of interest to investigators seeking to understand what enables the distress of a person like K.K. to vanish as she shifts into deep, intimate feelings of “being connected to the universe” the moment she looks up through a kitchen window and out at the distant stars.

4. Recent Functional MRI Research

Arcaro et al. tracked the responses of our lower visual pathways as they relay forward into the posterior part of the parahippocampal gyrus.15 Extra-large visual response fields reside in this posterior parahippocampal region. In addition, the visual associations in the superior visual fields are coded preferentially. They respond strongly to stimuli that register items throughout both the central and peripheral zones of whole scenes. These attributes would seem to fill almost all the optical requirements for a system that could deliver sharp visual clarity throughout a globally coherent spatial field. (Such a prescription might serve as a useful preamble for functions that we might later incorporate into what we regard as our mind’s eye). [ZB: 482–499]

Three sites in the right hemisphere normally help us process visual tasks in different parts of space (see also figure 11.1). After these sites were first identified by fMRI in individual subjects, their separate functions were disorganized by the effects of localized transcranial magnetic stimulation.16 These disruptions confirmed that tasks in far space engage the ventral occipital cortex. In contrast, tasks in near space engage the cortex higher up in the posterior parietal region. This region corresponds with the location of the egocentric E in figures 11.1 and color plate 1. However, our frontal eye field (FEF) functions are more flexible. The FEF can contribute its focal attentive, top-down functions either when we search for details in the near frame or in the more distant frame of spatial reference.

Huijbers and colleagues carefully studied the fMRI correlates and reaction times of 21 normal subjects who were engaged in different visual and auditory imagery tasks.17 Four regions proved crucial. The subjects activated these sites both when they succeeded in developing a mental image and when they retrieved this image later from memory. These four regions were the hippocampus, posterior cingulate cortex, medial prefrontal cortex and angular gyrus (see figure 3.1). All four, of course, are part of that larger (mostly medial) constellation of familiar network sites normally involved in the way we represent much of our egocentric psychic Self plus its intimate topographical details in our event memory.18 The two key regions forming the core of this macronetwork are considered to be the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the posterior cingulate cortex (pCC).

In a separate report, Huijbers et al point out that when human subjects deliberately work to retrieve their memories, they couple the hippocampus with these same three other regions of the default network.19 In primates, more than two-thirds (69%) of the place cells in the hippocampus are coded to respond allocentrically; only a minority (10%) express the egocentric frame of reference. [ZBR: 100–101] Could such imbalances in the percentages be different among those human subjects who begin as especially Self-centered individuals? We don’t know.

The preceding lines of evidence supplement those from direct personal experiences. They lead to a testable working hypothesis: a meditator’s more allocenteric spontaneous varieties of creative, insightful functioning could coalesce during casual instances—those that happen to combine looking up, selfless processing, and a loss of fear. In contrast, other spontaneous retrievals that remain more Self-centered may tend to be associated with personalized imagery that happens to be projected into vision at or below the center of a meditator’s gaze. [SI: 97]

5. Fear in Relation to Pathways through the Amygdala

Fear is a powerful emotion. The amygdala makes pivotal subcortical contributions to our fears.20 [ZB: 175–189] The useful phrase “weapon-focusing effect” is discussed by Axmacher et al.21 In this chapter, the words take on special meaning for two reasons: (1) with reference to that sharp kitchen knife lodged deep within subject K.K.’s fears for many decades, and (2) with regard to yet another incident that relieved suffering, described at the end of this chapter.

When a weapon causes fear, it intensifies the sharp focus of our spotlight of attention. Instantly, the impulses coding for fear diverge throughout the many hotline connections of the amygdala. Suffering continues for those unfortunate persons whose habitual ruminations follow only these well-worn, negatively charged fear pathways. What they need to do first is delete or bypass these resonant fear pathways at sites closer to their origin. Next—as William James foresaw—they need to mobilize other positive resources. The goal is not just to reinstate, but to build to its new optimum the full competence of their self-image.22 Research discussed in the next two sections clarifies how the human brain could achieve the first of these objectives.

6. Cortical Processing Pathways That Can Relieve Negative Emotions

The meta-analysis of PET and MRI research by Diekhof et al. examines how we can normally reduce our emotional over-reactions when events are threatening or unpleasant.23 For example, at the moment when a negative emotional event is being drained of its prior affect, the evidence suggests that an activation within the ventromedial prefrontal cortex could be the cause of (or be co-responsible for) the deactivation of the left amygdala. Moreover, when a person’s positive affect coincides with a broadening of their visual field, these two events can be associated with activation of the orbitomedial cortex.24 Importantly, activations down in this lower, medial orbital prefrontal region are also being correlated with a variety of useful, positive, improvisational modes of problem-solving behavior. [SI: 18, 45]

7. Deep Subcortical Gates in the Thalamus That Can Block Negative Emotions

Signals sent from the cortex, reaching adaptive mechanisms deep in the thalamus, can also shield the brain from an over reactive limbic system (see chapter 3). In this regard, Min has comprehensively reviewed the pivotal inhibitory role played by the reticular nucleus of the thalamus.25 Acting in its capacity as a bidirectional gate, the reticular nucleus is positioned to shut down aversive sensory, hypothalamic, amygdaloid, and other limbic anxiety signals. These messages could otherwise ascend to the cortex through the three limbic nuclei of the thalamus. In turn, the reticular nucleus can also shield our limbic system from being overinfluenced by stress signals descending from overdriven higher cortical regions.26 [SI: 87–94; 109–121]

An important practical point relates to GABA, the brain’s major inhibitory transmitter. When GABA is released from this reticular nucleus, it can regulate vision selectively in either the upper or the lower visual fields.27 Two lesser nuclei also serve to inhibit the limbic thalamus: the zona incerta and the anterior pretectal nucleus. [ZBR: 178–179] How could the GABA released by these three inhibitory nuclei regulate consciousness selectively? By nudging thalamo ↔ cortical oscillations out-of-phase. A simple analogy may help explain how the release of GABA might interfere with their synchrony. A noise-canceling headphone is currently advertised in many magazines. Its electronic circuits, powered by a tiny AAA battery, operate in a comparable manner. [MS: 35–37; 108–109] Try one out. Hear for yourself.

Zikopoulos and Barbas describe a novel, excitatory amygdalo → reticular pathway.28 Their findings clarify how some normal messages that speed from the amygdala into the reticular nucleus actually turn out to reduce the effects of excessive amygdala activity. This pathway’s extra-large nerve terminals directly stimulate the cell bodies of inhibitory neurons in the reticular nucleus. Therefore, the resulting extra release of GABA by these reticular nucleus nerve cells could provide a speedy feedback to block overdriven mechanisms in the limbic thalamus that could otherwise relay up to overstimulate the cortex. Another important fact is that two key pathways converge on the reticular nucleus. This dual convergence of information about attention and emotion helps clarify a model of kensho. It suggests how, when a triggering stimulus captures attention, the resulting over-reactivity of the anterior reticular nucleus could serve to inhibit those limbic nuclei of the dorsal thalamus that are specialized to subserve emotional functions. [SI: 109–117]

Does the Technique of Gazing Up and Out Involve Eye Movement Desensitization?

This chapter describes reimaging and reprocessing mechanisms linked to gentle elevations of the usual line of sight. They differ substantially from the deliberate repetitive, to-and-fro, sensorimotor sequences proposed as mechanisms during active eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR).29 Transient, active, fast eye movements from side to side can briefly reduce the vividness and emotional resonances of traumatic images that are revisualized from the past, although such results are not invariably sustained.30 Notably, the original relief from major traumatic stress has been sustained for at least seven years in case 1 and for more than three years in case 2.

No descriptions in the EMDR studies just cited, or elsewhere to my knowledge, specify the particular angle and distance inside the vast volume of space where the subjects were projecting their imagery. One comment from the early report by Shapiro is of interest: “Vertical movements appear to have a calming effect and are particularly helpful in reducing extreme emotional agitation, dizziness, or nausea.”31

Caveat

The author’s goal in these pages is to stimulate other investigators to rigorously challenge this empirical approach. Many people of all ages have the capacity to infuse emotions and auditory memories into the scenes that they revisualize in their mind’s eye.32 No guarantees can ensure that every person who tries to revisualize while gazing up and out will immediately be relieved of psychic trauma in ways superior to current somatic experiencing or cognitive techniques.33 Each subject in the two case reports is familiar with her own psyche and with psychological processes in general. Other subjects may lack the requisite neural capacities, as described by Huijbers et al., 34 that could enable them to visualize and reprocess as effectively as these two intelligent women.

Weapon Focusing in Another Case Report

In case report 1, K.K. described how she had been suddenly released from major fears linked to a knife. This happened during a brief, extraordinary, involuntary state of consciousness. A knife is a potent weapon for arousing fear. Wielded by an assailant, its edges slash and draw blood, its point plunges deep. A knife can also be turned inward against oneself.

Suzanne Foxton recently described a remarkable alternate state experience.35 Why is her account of this state relevant to some aspects of case 1? Because this experience served as a pivotal turning point in her life. Following this, Foxton recovered from her actively suicidal severe depression. Her narrative, like that of K.K., further illustrates how a novel perspective that looks up and out—when associated with a sudden shift into an unusual state of consciousness—evolves into a major release from deep-seated damaging emotions that have lasted a long time.

It began in the kitchen. Foxton was washing up knives at the sink. Abruptly, the “biggest, most dangerous knife became very ‘knife-ish’ . . . There never was a more perfect knife . . . It was just as it should be, as everything is.” At that moment, “I then just saw that everything had always been like that, the whole time.” [But] something like the ego “had been [standing] in the way of it. Whatever I was looking for was this knife and whatever else happened to be around.”

By this time she had entered into the depths of a profound experience that had opened into “boundlessness.” Overcome by this state, she next found herself “crouching on the kitchen floor, saying ‘Whoa!’” She then wandered around the kitchen, repeating aloud: “It’s so obvious.” This repetition of the word obvious is intriguing. It has a long history that links it with the extraordinary, fresh living experience of an alternate state of consciousness.36

The entry of what she calls a “physiological phenomenon” also makes her narrative noteworthy. Her words describe it as a novel perspective that began in association with the sense that her consciousness was undergoing a kind of awakening. It enabled her to “see things slightly above the usual where the eyes come out.” When she illustrates the origin of this elevated point of view, she looks up into the space to the right of her head.37 She also describes it on another occasion as feeling “like I was seeing from just next to the right of my head and a little higher than my eyes.” Following this acute, dramatic experience of psychological release in the kitchen, her psychiatric condition gradually improved. Since then, her ongoing awareness has become focused on each event as it arises in the present moment: “nothing is happening that’s not happening right now, right now.”

Commentary

The two mature women in cases 1 and 2 found it empirically useful to be looking up and out into the distance when they revisualized earlier incidents of severe emotional trauma. Their relatively simple technique seems to involve mechanisms other than (1) a soft optical sense of being visually distanced from events at the moments when they are recalling a traumatic scene, and (2) a motion-induced optical blur of this scene while it is being recalled.

During the approach they describe, subcortical and cortical networks appear to tap into deeper physiological levels of attentive processing. This reprocessing seems to develop a powerful momentum. The brain appears to be shifting into an altogether fresh, objective perspective. The results can be transformative: an abrupt, sustained release from deep fears—fears that for many years had been narrowly focused down on a bleeding hand, cut by a knife, or had been caught up in a desperate struggle at night in the front seat of an automobile.

Thoreau appreciated the space outdoors, and observed that we had plenty of this available space that opened out beyond our own elbows into the distant horizon.38 The evidence reviewed converges from multiple lines of research. It suggests that fresh, creative potentials can open up when humans access the global properties of this mental space, 39 including that which extends above their usual visual horizon.

Who else might benefit from the novel dynamic reprocessings that evolve as they visualize and revisualize from an elevated perspective? This review is intended to illustrate that several kinds of rigorous behavioral, neuroimaging, and evoked potential evidence will be required to critically address each dimension of this important question.40

Evidence presented in this chapter and earlier explains why it can sometimes be an advantage for meditators to elevate their attentiveness and awareness into the upper visual fields.41 [SI: 113–116; MS: 74–91] These empirical suggestions find independent confirmation in recent recommendations of different techniques that can support a mindful meditative practice. This teaching about adopting an elevated gaze is offered by the well-credentialed Zen teacher and physician Jan Chozen Bays.42 She aptly entitles her chapter “Look Up!”

Chapter 12 examines other evidence that correlates the lesser wiring cost and early orientation of our lower brain pathways with visual phenomena of a different kind. These phenomena involve colors and emerge spontaneously during meditation. They can also lateralize and become referable to the upper visual fields.