2

History of Magic in Iceland

There is an unusually large amount of information about many aspects of the practice of magic by the Icelanders that amounts to much more than any other non-Greco-Roman European people. The Icelanders left behind a clear record of their magical beliefs and practices and have also given us some clear ideas about the contexts in which this magic was practiced. Not only do we have original pagan sources (in the Poetic Edda and skaldic poetry) but also some clear reflections of pre-Christian practices set down in saga literature. The sagas are prose works of literature. Written down for the most part between 1120 and 1400, these semi-historical tales usually reflect events and beliefs of the Viking Age (about 800–1100).

THE PRE-CHRISTIAN AGE

Icelandic sagas sometimes feature the working of magic and give us vivid pictures of the lives of several magicians. The most famous of these is Egil’s Saga. This is essentially a biography of Egill Skallagrímsson (910–990), an Icelandic skaldic poet, runic magician, and follower of the god Óðinn. From later periods we have the rare finds of actual manuals of magic. Along with runic inscriptions, legal records, and other documents, these works provide correlations to the “literary” material and fill in some of the gaps left by the sagas and poems.

As with other aspects of Icelandic history, the earliest phases can be divided into the pre-Christian and Catholic periods. The later Reformation or Protestant period changed the picture considerably. It was during the Protestant Age that most of the books of magic were created, but in order to make any headway in comprehending the magical worldview of these magicians it is also necessary to understand the cosmos of the Germanic heathen past.

As should be clear from the previous discussion of the history and character of the church during the Catholic period, the mixture of pagan and Christian elements prevalent in Icelandic culture shows how and why we are able to use documents actually written down in the Catholic period as somewhat reliable sources for the heathen practice of magic. As far as magic is concerned, this was really more an age of synthesis than a radical departure from the past, and the same holds true for other aspects of the older culture.

The accounts we have make it clear that in the later pagan age there seem to have been two kinds of magic being practiced: galdr (Modern Icelandic spelling: galdur) and seiðr (Modern Icelandic spelling: seiður). These appear to have taken on some moral connotations—the galdr form being more “honorable” and the seiðr form often considered “shameful” or “womanish”—although originally there were probably only certain technical (and perhaps social) distinctions between the two. The Old Norse word galdr is derived from the verb gala, “to crow, chant,” and is therefore marked by the use of the incantational formula that is spoken or sung, and perhaps also carved in runes. The original meaning of seiðr may also have something to do with vocal performance (i.e., singing or chanting), although the exact original meaning of the word remains unclear. It is derived from the verb síða, “to enchant.” One thing is certain, however: contrary to the claims of some modern authors, the word has nothing to do with “boiling” or “seething.”

There are clear procedural and psychological distinctions between these two magical techniques. The practice of galdr is more analytical, conscious, willed, and ego oriented, whereas seiðr is more intuitive and synthetic. Typical of the galdr technique is the assumption of a “magical persona,” or alter ego, for working the will. In seiðr, by contrast, a trance state is induced in which ego-consciousness is temporarily obliterated. It has also sometimes been said that seiðr is closer to what is commonly thought of as “shamanic” practice. It should also be pointed out that although these are two real tendencies in Icelandic pagan magic, the moral distinction appears to be a later development. Óðinn is called the “father” of galdr (ON Galdraföðr) and its natural master, but it is also reported that he learned the arts of seiðr from the Vanic goddess Freyja.

One traditional field of Germanic magic from which the galdur of our texts inherits many of its methods is that of “rune magic.” The runes (Ice. rúnar or rúnir) form a writing system used by the Germanic peoples from perhaps as early as 200 BCE. The use of runes survived into the early nineteenth century in some remote areas of Scandinavia. Such runes, or rune staves (Ice. rúnstafir) as they were often called, were at first used for non-profane purposes. By around 1000 CE they began to be used increasingly for ordinary communication. The word rún in Icelandic signifies not only one of the “staves,” or signs, used in writing, but also the idea of a “mystery,” “secret,” or “body of secret lore.” This idea of “secret lore”—which in fact reflects the original sense of the word rún—was then transferred to the phonetic signs (writing) that made communication over time and space possible.

Just before the inception of the Viking Age, the last pagan recodification of the runes took place. It was out of this time period that many of the pre-Christian aspects of magical practice found in the historical books of Icelandic magic seem to have grown. As in earlier times, each rune had a name as well as its phonetic value (usually corresponding to the first sound in its name). There were also interpretative poetic stanzas connected to each rune. These are of great interest to us as they were recorded in Iceland and Norway in the 1400s and 1500s, a time period that is actually quite close to when our earliest texts of galdor magic were composed. We can be fairly certain, therefore, that the galdramenn (magicians) had some detailed knowledge of the esoteric lore of pagan runology. Many of them were certainly literate in runes. The system of the Viking Age runes, as it would have been known to the Icelanders, is shown in table 2.

Several things can be learned directly from this table about the significance of what we encounter in the spells discovered in historical books of magic. The number 16 is often found underlying the composition of the stave forms in the spells. Most often these are not actual rune staves; rather they tend to be stylized magical letters or abstract symbols. However, they do reflect the formulaic significance of the number 16, which is the total number of runes in the Viking Age rune row. Additionally, the rune names occur in the spells themselves, where they apparently signify the corresponding runes. Certain rune names, such as hagall (hail), also show up in the technical names of the special “magical signs” (Ice. galdrastafir) themselves.

In pre-Christian times rune magicians were usually well-known and honored members of society. In the Northern tradition, runelore had been the preserve of members of an established social order interested in intellectual or spiritual pursuits. Most commonly these men were followers of the god Óðinn, the Germanic god of magic, ecstasy, poetry, and death. Historically, men were more often engaged in rune magic than were women—a social phenomenon that is reflected in the later statistics concerning witchcraft trials in Iceland. These statistics show that men were more likely to be accused of practicing witchcraft than were women.

In pagan times the technique of rune magic consisted of three main procedural steps, as follows:

- carving the staves into an object

- coloring with blood (or dye)

- speaking a vocal formula over the staves to load them with magical power

The basic components of this direct technique, which is not dependent on any intervention by gods or demons, will later be continued in the historical galdrabækur. This direct mode of operation clearly shows the continuation of a practice from early Germanic times right up to the modern age. It must also be noted that the technique is generally thought to have to be performed by a qualified rune magician. This is true of most traditional forms of magic.

Old Icelandic literature contains some examples of this kind of magic. One of the most interesting examples is found in the Poetic Edda in the poem called, alternately, “För Skírnis” or the “Skírnismál” (st. 36). This poem dates from the early tenth century. In it the messenger of the god Freyr, who is named Skírnir, is trying to force the beautiful giantess to love his lord, Freyr. Skírnir threatens her with a curse.

| Þurs ríst ek þér | A thurs-rune I carve for you, | ||

| ok þría stafi | and three staves (they are)— | ||

| ergi ok œði | wantonness and frenzy | ||

| ok óþola; | and torment; | ||

| svá ek þat af ríst | I shall scrape it off | ||

| sem ek þat á reist, | as I scratched it on, | ||

| ef gøraz þarfar þess. | if it becomes necessary. |

The basic stance of the rune magician that we see here, as well as the technical aspects such as the enumeration of the staves and the actual style of the incantation, will be likewise found in the practical workings that appear centuries later in Icelandic books of magic.

One other famous example that clearly shows rune-magic techniques is found in Egil’s Saga (ch. 44). Here we see Egill detecting poison that had been put in his drinking horn:

Egill drew out his knife and stabbed the palm of his hand. He took the horn, carved runes on it, and rubbed blood on them. He said:

I carve a rune on the horn

I redden the spell in blood

these words I choose for the horn . . .

The horn burst asunder, and the drink went down into the straw.*5

In addition to rune magic, and sometimes combined with it, we find workings used in pre-Christian times that make use of certain magically potent natural substances. In fact there was a whole magical classification system of sacred woods only partially reflected in the galdrabækur. It appears that woods of various trees played a special part in Germanic magical technology as well as its mythology. The cosmos is said to be formed around the framework of a tree called Yggdrasill. In the “Völuspá” (sts. 17–18) humankind is shown to have been shaped by a threefold hypostasis of Óðinn-Hœnir-Lóðurr from trees: the man from ash and the woman from elm.

Blood is another substance of extreme importance. Runes were often reddened with it, and it was generally known to have intrinsic magical powers, especially when the blood was that of the magician himself. In many pre-Christian sacrificial rites the blood of the animal was sprinkled onto the altar, temple walls, and even the gathered worshippers. Everything was thought to be hallowed by this contact. Actually, the etymology of the English verb “to bless” reflects this heathen practice. The word is derived from the Proto-Germanic form blōðisōjan (“to hallow with blood” from PGmc. blōðam, “blood”).

Herbal substances were also widely used in pre-Christian magical practice. Some of the most powerful of these were species of leek (Ice. laukur), the name of which commonly occurs as a magical runic formula even as early as 450 CE. Several herbs also bear the names of Norse gods or goddesses; for example, Icelandic Frigg jargras (“Frigg’s herb”)*6 and Baldursbrá (“Baldur’s brow”).†7

CATHOLIC PERIOD

As will be remembered from our discussion of the politico-religious history of Iceland, a peculiar kind of Catholic Church existed in Iceland from 1000 to the middle of the 1500s. In all facets of life this represented a period of religious syncretism in which elements of the ancient native heritage and the new foreign religion were being blended together. This is the period just prior to the time when the Icelandic books of magic began to be composed.

Pagan elements would naturally tend to be diminished over time, both as new material was introduced and as knowledge of the technical aspects of the pagan tradition began to fade through neglect and lack of old established support. Nevertheless, the old material and techniques continued in a real way for many generations. In many respects, however, this is a “dark age” for our knowledge of the actual practice of magic in Iceland. This is because the works composed at this time tended to depict earlier Viking Age practices, and we have no actual galdrabækur from the period itself.

There are a number of runic inscriptions from Scandinavia that help fill in the gap in our knowledge of the time; for example, the magical formulas found in Scandinavia from this period, which make use of (often defective) Latin formulas executed in the runic alphabet. This shows the blending of the Christian and pre-Christian cultures. The fact that the Latin is often riddled with grammatical errors demonstrates that these inscriptions were probably executed by laymen or young students. However, a few inscriptions are grammatically flawless, which shows that some members of the well-educated clergy also indulged in these arts. On the one hand, the fact that the formula is in Latin demonstrates the mythic dominance of Christian symbolism in the magician’s world, but the fact that the inscription is executed in runes also shows that the old runic symbolism provided something to the inscription that the Latin alphabet was thought to lack.

A medieval rune stick found in Bergen reads:

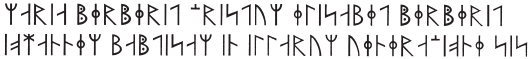

Fig. 2.1. maria perperit cristum, elisabet perperit iohannem baptisam in illarum ueneracione sis absolutaøcsi inkalue dominuste uacat adlu[cem]

Maria perperit Christum, Elisabeth perperit Iohannem Baptistam. In illarum veneratione sis absoluta! Exi, incolea! Dominus te vocat ad lucem!

“Mary gave birth to Christ, Elizabeth gave birth to John the Baptist; in their veneration be absolved. Come out child, with hair! The Lord calls you to light!”

This is a Christian magical formula to allow for easy childbirth. It was believed that a child born with hair would be healthy.

Based on what we see in later material, it is possible to speculate that many features of the pagan tradition were kept alive for a long time but that eventually these were blended together with elements from the Christian medieval tradition that had come to the North during the long Christianization process. It must, however, be understood that practicing magic in the first place was considered by orthodox Christian dogmas to be heretical and even diabolical in and of itself. This may explain why there appears to have been an active, explicit merger between the old gods and the demons of hell, and even why demonic entities can appear in spells next to apparently orthodox religious figures such as Raphael or the Savior.

Christian influence on the tradition was most clearly seen in new elements introduced into the formulas. These include personalities from Judeo-Christian mythology such as Solomon, Jesus, and Mary. In addition to these figures, certain formulas were also incorporated during this period: the invocation of the Trinity, (Latin) formulas of benediction peculiar to the Catholic Church, the “Our Father” in Latin, and so on. Other elements, such as Judeo-Gnostic formulas (for example, Jehovah Sebaoth [Yahweh Tzabaoth], Tetragrammaton), must have come directly from magical books imported from the Continent. With regard to the actual methods of working magic, there was a shift in emphasis to the prayer formula in which the magician bids for the intercession of some supernatural entity on his behalf. Although this was known to some extent in the pre-Christian age, it had limited application. However, this form predominates as a mode of operation in the Judeo-Christian tradition.

We only have indirect information about magicians and magic of this period. Many texts were composed in this period, but they mostly harked back to the Heathen Age when magic came into play. Later folktales, for the most part collected in the 1700s and 1800s, report on one famous magician of this early age: Sæmundur Sigfússon the Wise (1056–1133). He was the goði (priest-chieftain) of Oddi. He is reputed to have been the most learned man of his time, but all of his writings are now lost. His fame was such even into modern times that the collection of poetry that came to be known as the Poetic Edda (or Elder Edda) was originally ascribed to him and called the Sæmundar Edda. Furthermore, he was said to have acquired a great deal of magical knowledge as a captive of the “Black School of Satan.” This legend most likely stems from the fact that he was one of the first Icelanders to study Latin and theology on the Continent. Despite the supposed origin of his magical knowledge, Sæmundur had the reputation of being a “good” magician. The designation of “white” or “black” magic that the historical magicians acquired was due more to literary stereotyping and regional conflicts than to any historical or practical facts. Sæmundur’s sister Halla also “practiced the old heathen lore,” as one text describing her puts it, although the writer feels obliged to add that she was “nevertheless . . . a very religious woman.”*8

PROTESTANT PERIOD

When Protestantism was introduced in Iceland beginning in about 1536, a radical new situation came into being. As learning decreased in quality for a time and persecutions of magic increased in intensity, elements of Icelandic magic already in place began to be increasingly admixed with elements from previously rejected paganism. The result of this was that the new Protestant establishment in some cases equated elements of Catholic practice with pagan lore.

As the Catholic period drew to a close, there lived two contemporary Icelandic magicians with very different reputations. One was Gottskálk Niklásson the Cruel (bishop of Hólar from 1497 to 1520), who had a reputation as an “evil” magician. He was said to be the compiler of the fabled Rauðskinna book of magic (further discussed in chapter 7). Gottskálk is otherwise well known in Icelandic history as a ruthless political schemer who conspired against secular political figures for his own benefit. This bad reputation is probably the real source of his image in the folk tradition. An approximate contemporary of Gottskálk was Hálfdanur Narfason (died 1568), vicar of Fell in Gottskálk’s diocese of Hólar. Little is known of Hálfdanur’s life, but there is a rich body of folktales concerning him. He appears as the legendary “white” counterpoint to the “black” bishop, Gottskálk.

Hálfdanur and Gottskálk stand at the gateway of transition between the Catholic and Reformation Ages in the history of Icelandic magic. Much later on in the Protestant period we again meet with a pair of strongly contrasted magicians: Eiríkur and Galdra-Loftur (Loftur the Magician). Eiríkur was a quiet and pious vicar who lived from 1637 to 1716. He is little known in history but shares with Sæmundur the reputation of being a practitioner of good magic, wholly derived from godly sources. This reputation was maintained despite the fact that he was not above practicing the most dreaded arts, such as necromancy, for “pedagogical purposes.” Here I refer to one of the most telling anecdotes in the history of Icelandic magic—one that emphasizes the character, courage, and level of humor necessary to practice magic. This passage about Eiríkur testing two different boys who wanted to learn magic from him is translated in chapter 7.

This episode might be compared with part of the story about Galdra-Loftur in which he is supposed to have committed one of his most depraved acts—raising the draugur (ghost) of Bishop Gottskálk in an effort to take from his ghost the famous “black book,” Rauðskinna, which had been buried with him. Not much is known of the historical Loftur other than that he was a scholar at the school of Hólar and he died in 1722. Galdra-Loftur is generally regarded as a kind of Icelandic Faust whose major “sin” lies in his insatiable desire for more knowledge and power. A translation of a passage from this folktale is presented in chapter 7 of this book as well.

As a result of Iceland’s unique church organization during the Catholic period, together with the general isolation of the country from Continental affairs, the practice of magic was not officially persecuted or prosecuted during that time. The Inquisition became active on the Continent following Pope Innocent III’s bull of 1199. This papal bull was primarily directed against what were believed to be organized heretics. Over time its authority widened to include sorcery, even when heresy was not involved, as was made clear in a bull by Pope Nicholas V in 1451. But even this failed to penetrate the dark mists of Thule. This phenomenon is probably in large part due to the fact that in Iceland it was clergymen themselves who were most actively engaged in sorcery!

Later on Protestants on the Continent were no less severe in dealing with witchcraft than the Catholic Inquisition had been, and in many cases they were more devastating since their focus on individuals and small groups tended to lead to indiscriminate persecutions. It was under the cover of the Reformation that real witchcraft persecutions came to Iceland. These persecutions never reached the genocidal levels known on the Continent, and especially in Germany, where hundreds of thousands were executed, but they are still historically significant for the small country of Iceland.

Some of the moral attitudes demonstrated by Icelanders toward magic being either good or evil may also go back to pagan sentiments. It would be a great mistake and error to assume that in pre-Christian times there was no such thing as “evil magic.” Many of the spells of Óðinn reflected in the “Hávamál” are directed against evil sorcerers or witches. Clearly in pagan times the good was judged to be that which promoted the general welfare and defended humans, productive animals, crops, and so on. Evil was thought to be that which was destructive of good things or detrimental to the general welfare of the people, animals, or life in general. In Christian times, by contrast, the “good” was judged to be that which promoted the interests and dogmas of the church, and evil was anything set against these. The morality of the Icelandic magician was generally that of the pagan past, with little regard for the sources of the symbolism used.

The earliest trial for witchcraft in Iceland is recorded in 1554; the last such trial is recorded at the Althing of 1720. It must be said that records were poorly kept in this period, but it is estimated that during this time some 350 trials were held, although records for only 125 survive. Of these 125 accused persons, only 9 were women.*9 Obviously this is in stark contrast to the usual pattern of witchcraft accusations and suggests something of the demographics of actual magical practice in Iceland. It is also a general reflection of established Germanic tradition, where men were at least the equal of women when it came to the “occult” arts. Records exist for only twenty-six executions for witchcraft. These were mostly carried out by burning. Of the cases against female witches, only one woman was actually executed. Others who were convicted of this crime, but whose sentences were short of death, were flogged or outlawed. Outlawry meant that they were in effect banished from the country and sent into exile abroad.

Clearly the period of the most intensive witchcraft persecutions was between the first execution in 1625 and the last in 1685. However, it is worth noting that during this time Iceland suffered under a moral code of extremely harsh laws. These provided for capital punishment for a wide variety of crimes—murder, incest, adultery, theft—as well as witchcraft. Even finding rune staves carved on a stick or written on parchment was evidence sufficient to convict someone of witchcraft. This is a far cry from the saga age when great men knew the runes and the Althing could not impose the death penalty! It is also worth pointing out that although it was not necessarily the poorest or most ignorant people who were accused of sorcery, the rich and powerful or the scholarly (who were the chief practitioners, historically) were, for the most part, immune from prosecution.

In the period between 1550 and 1680 Iceland developed a form of magic that was practiced by members of the highest levels of its society. The fact that this synthesis survived as long as it did, however, is perhaps due to the relative lack of a strict set of socioeconomic and educational class distinctions in Iceland. Even today Icelanders are noted for their strong beliefs in occult matters and their general pride in their pagan past.