4

The Gods of Magic

Æsir, Demons, and Christ

In the practice of Icelandic magic, the magician tended to appeal to every sort of entity he knew of to effect his will. It did not matter whether it was the Christian God, a demon imported to the North through Christianity (such as Beelzebub), or one of the old native gods or goddesses. No one was excluded. All of them were thought of as possible sources of power, and none of them was especially feared.

In the Icelandic tradition the old gods and goddesses of the Germanic peoples had an uncanny way of surviving in the world of magic and folklore. Only isolated sources mention these old deities in the oldest written materials from Germany, England, or even from other Scandinavian areas. But in Iceland we find a widespread and vigorous life for the old gods. The reasons for this should be obvious from what we have already said about the peculiarities of Icelandic socio-religious history.

In what follows we will examine the whole picture of the “theology” and/or “demonology” presented in Icelandic magical texts. It is our main aim to observe the survival of pagan divinities, but we will also look at their relationship and apparent assimilation to the mythomagical figures from the Judeo-Christian tradition, both the ones thought to be evil as well as the ones thought to be good.

THE PAGAN GODS AND GODDESSES

In every mythic tradition over which Christianity was laid—including the Germanic—pre-Christian divinities survived in at least two ways. The first was by being driven “underground,” where they often lived alongside the other rejected entities (classified as demons). The second way was by being assimilated into accepted or established entities. This latter way can be called the syncretic method. It was by far the more common scenario throughout all traditions. Occasionally and for a time the old gods could be identified with Jesus, his disciples, the apostles, and most commonly with various saints and archangels. Sometimes these saints were preexisting ones, but in other cases there was a virtual canonization of the old divinities under new, Christianized names and circumstances. Here we are only concerned with those instances found in magical contexts, but it is worth realizing that this was a general and widespread phenomenon not limited to the area of magic. This whole process deserves its own separate study.

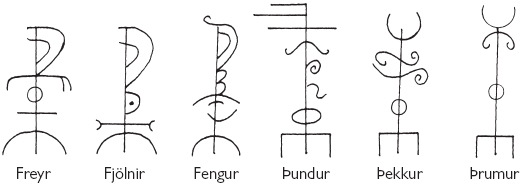

In the Icelandic sources the most vigorously represented of the old gods is the Galdraföðr (Father of Magic), Óðinn. This should not surprise us. His name not only appears in virtually every litany of names of the old gods, but also his heiti (Ice.: bynames, or nicknames) often occur as names of magical signs or in other litanies. By way of example, Jón Árnason records a series of six galdrastafir, each of which has a distinctive name*11 (see figure 4.1 below). Of these six names—Freyr, Fjölnir, Fengur, Þundur, Þekkur, and Þrumur—four (2–5) are well-attested heiti belonging to Óðinn. These as well as other nicknames of Óðinn that appear in Icelandic black books show that knowledge of the complex lore of Óðinn’s various aspects was kept alive, in addition to the more basic ideas about his functions in Norse myth. When we examine these spells we soon discover that Óðinn is found in all sorts of company, and his name is used for a wide spectrum of magical purposes. There is great evidence of continued active knowledge of Óðinn and his magical functions, even if some of this knowledge has been corrupted.

Fig. 4.1. Six galdrastafir recorded by Jón Árnason

The god Þórr is another one of the old deities who is very actively

represented in magical lore. This is not surprising either, as he was the

most popular god in pagan Iceland. In the old books of magic his actual

name is often represented in litanies of divine and “demonic” names.

But there is also evidence that shows that Þórr’s magical role in Iceland

was most significant through a galdrastafur called Þórshamar (Þórr’s

hammer). This name for a sign was actually attached to several different

forms over a long span of time. Perhaps originally it was identified

with the solar wheel, or swastika. The name and certain variants of the

galdrastafur

are also recorded in the folktale material of Jón Árnason.

He shows the form

, which is reminiscent of the old solar wheel.

Here we are also reminded of the older Viking Age runic inscriptions,

which contain the powerful formula Þórr wigi, “Þórr sanctify or hallow.”

Here the idea of sanctifying or hallowing a place (or even the

runic inscription and object itself) means that they are protected, set

apart from the profane, and empowered by divine force.

, which is reminiscent of the old solar wheel.

Here we are also reminded of the older Viking Age runic inscriptions,

which contain the powerful formula Þórr wigi, “Þórr sanctify or hallow.”

Here the idea of sanctifying or hallowing a place (or even the

runic inscription and object itself) means that they are protected, set

apart from the profane, and empowered by divine force.

In addition to these two highly prominent divinities mentioned in several spells, at least another two of the older divinities’ names appear as components of certain herbs. We have Friggjargras (Frigg’s herb) and another herb is called Baldursbrá (Baldur’s brow). Frigg was the wife of Óðinn, and Baldur was one of his sons. Baldur was known for his invulnerability and his physical perfection.

One whole myth is obliquely alluded to in spell 46 of the Galdrabók, which says: “May you become as weak as the fiend, Loki, who was snared by all the gods.” This clearly demonstrates that mythic material otherwise recorded in the Poetic and Prose Eddas was well known to the galdramaður who composed the spell.

Although there are some spells in which single Germanic god names appear, it is more usual for them to be used in litanies of names. There are several things worth noting about these litanies. They contain the names of the great gods and goddesses of the ancient Germanic religion, but they do not seem to be organized in any especially meaningful way with regard to the pagan mythology. Also, the last three of these litanies that appear in the Galdrabók (in spells 43, 45, and 46) are really syncretic compositions in which the Germanic names appear right alongside names from Judeo-Christian and Mediterranean myth and magic. However, the overall impression is that the Judeo-Christian elements are newcomers in an already established magical system.

Perhaps one of the most interesting survivals is the name of the dwelling place of the gods, Valhalla (Ice. Valhöll). Valhöll is the “hall of the slain” (or perhaps the “hall of the chosen or elect”) and is held to be a dwelling place in Ásgarður (court of the gods) in which Odinic warriors who died in battle are honored in the supernal realm. This shows a certain continuance of cosmological traditions from the heathen past, which impressed itself upon the structure of the new entities coming to the North.

CHRISTIAN DEMONS

Not only are the old gods of the Germanic peoples said to be in Valhöll, but in the view of the galdramenn who wrote the Galdrabók, so too were the demons of Hebraic mythology—Satan and Beelzebub—to be found there. The most revealing formula is found in spell 43 of the Galdrabók, where we read: “Help me in this, all you gods: Þórr, Óðinn, Frigg, Freyja, Satan, Beelzebub, and all those gods and goddesses who dwell in Valhöll.” The fact that Satan had come to Valhöll was a significant event in the history of Icelandic magic. This symbolically and eloquently shows how the southern magical elements were at first assimilated in the North on terms set by the Northern tradition.

From the standpoint of the new establishment culture, however, this had the net effect of diabolizing the old Germanic gods. To a great extent, but certainly not exclusively, the old gods were equated with devils in the Christian mind. As time went on, especially beginning at the time the Galdrabók was compiled, aggressive magical spells would be more likely to use the old gods or demons in their formulas, whereas protective spells were more likely to make use of Christian elements. This is obviously not a hard-and-fast rule but rather a general tendency.

As noted earlier, the old characteristics and functions of the multifaceted traditional deities were increasingly dichotomized under the influence of the rather Christian dogmas, so for a while the old gods could feel at home alongside either Jesus or Satan. But when all was said and done, because of the nature of Christian doctrine, the old gods and goddesses of Valhöll ultimately found the company of demons more accommodating—at least in a magical context.

It might be convincingly argued that the way had been prepared for this process in Scandinavia centuries earlier. That is because the Christianization of various Indo-European peoples (Greeks, Romans, Celts, and the kindred Germans) was generally accomplished by the same combination of assimilating and diabolizing their native gods. Assimilation, or syncretization, took place covertly, while diabolization and demonization was often quite overt. It is no wonder, then, that the pagan deities of the North—or, more precisely, their sympathizers and followers—would recognize their kith and kin in the guise of the Christian “devils.”

On the other hand, and especially in the Catholic period, the new religion was itself heavily impressed with pagan ideas. Certain aspects of the old faith were superficially Christianized, and many of the old traditions were given a Christian veneer. In the world of the magicians this meant that Christian figures could sometimes be used right next to pagan deities. And as our wondrous example in spell 46 of the Galdrabók shows, the northern sorcerer was so free magically that he could use the names of Óðinn, the Savior, and Satan in the same litany. This spell, reproduced here for historical purposes only, reads in its entirety:

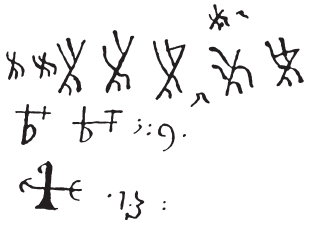

Write these staves on white calfskin with your blood. Rouse your blood from your thigh and say: I carve you eight áss (runes) [a], nine nauð (runes) [n], thirteen þurs (runes) [x], which are to afflict your belly with great shitting and shooting pains, and all these may afflict your belly with very great farting. May your posts (= “bones”) split asunder, may your guts burst, may your farting never stop, neither day nor night. May you become as weak as the fiend, Loki, who was snared by all the gods. In your mightiest name Lord God, Spirit, Creator, Óðinn, Þórr, Savior, Freyr, Freyja, Oper, Satan, Beelzebub, helper, mighty God, (protect) with your followers Uteos, Morss, Nokte, Vitales.

It might also be true that many times when the words “lord” (Ice. dróttinn) or “God” (Ice. guð) are used, they are not free of heathen connotations, as both words were in full use in pagan times.

It would be a mistake to ignore the many uses of Christian mythology in the historical Icelandic spells. Biblical stories are used as analogical models for magical operations, and the names of various figures from Judeo-Christian myth and legend are used as names of power. It is only important to realize that it is for the sake of power and effectiveness that they are being invoked. A sense of Christian piety is generally absent in the spells as we find them in historical books.

The Icelandic “magical triangle” of Germanic entities, Christian entities, and Christo-demonic entities is a peculiar one in that the old gods remained stronger in Iceland than anywhere else, and they survived most vigorously in magical practice. Even in folktales “old [that is, heathen] knowledge” (Ice. forneskja or fornfræði) is equated with sorcery. Furthermore, it seems that taken as a whole, and as far as magic is concerned, the demonic entities were never quite as “evil”—nor the Christian figures never quite as “good”—as they seem to have been in other regions.