Military flying organizations like to plan missions and practice them while they can still make changes and iron out the bugs. Launching on an unplanned mission builds feelings of anxiety. The support isn’t there. They don’t have the right people available. Communications are uncertain. They don’t know where they are going and there are no maps. There are no clear instructions on what to do when they get there.

That’s one big difference between peacetime operations and combat. In combat, you do what has to be done using whatever and whoever is available at the moment. The Rustics started like that.

On June 19, 1970, The U.S. Twenty-fifth Infantry Division had already pulled out of Cambodia. Their USAF FACs, call sign Issue, were based at Cu Chi and Tay Ninh and weren’t busy because of the Cambodian pullback. The FAC Air Liaison Officer at Tay Ninh was Maj. Richard Rheinhart. He took a phone call telling him that he and his FACs would be flying deep into Cambodia starting tomorrow. Their call sign would be “Rustic.”

The pilots’ normal large-scale (1:50,000) topographical maps covered only about 12 miles (20 kilometers) inside the Cambodian border. That was the limit of the incursion into Cambodia. Using small-scale aerial charts, the pilots did some “back of the envelope” (rough) fuel calculations. The OV-10 could make it well into Cambodia, but it couldn’t stay very long. It didn’t carry that much fuel.

Meanwhile, Lt. Col. Jim Lester, an OV-10 FAC and a staff officer at the Twenty-fifth Infantry Division Headquarters at Cu Chi, also got a phone call. His was from Col. Perry Dahl, the commander of the III Corps Direct Air Support Center (DASC) at Bien Hoa. The news was that Jim had a new job. He was to position six OV-10s and eight pilots at Tan Son Nhut and report to the Seventh Air Force Tactical Air Control Center for instructions. Jim had himself and Lt. Lou Currier available at Cu Chi. He had Maj. Dick Rheinhart at Tay Ninh along with Capts. Anthony McGarvey and Roger Dodd, and Lt. Dave Van Dyke. He located Capt. Paul Riehl and Lt. Dave Parsons, who were flying out of Song Be under the Rash call sign and supporting the U.S. First Cavalry Division. Those were the original cadre of Rustics and Jim Lester was their first commander. Jim had planned and led the FAC support for the Cambodian incursion and was an excellent choice for the job.

That night, June 19, Capt. Jerry Auth actually flew the first Rustic mission and did it in an O-2. In the early evening of June 19, Seventh Air Force decided they needed a FAC over Cambodia as soon as possible because of the situation at Kompong Thom. They went directly to Maj. Jim Hetherington, commander of the O-2 Sleepytime operation at Bien Hoa Air Base. The Sleepytime FACs flew primarily at night providing air surveillance over the Saigon area and Seventh wanted a highly qualified O-2 FAC to report immediately to Seventh Air Force Tactical Air Control Center for a special mission. Jim’s instructor pilot, Capt. Jerry Auth, was already airborne, checking out Capt. Bob Virtue, a newly arrived FAC. Jim contacted Jerry on the radio and told him to land immediately at Tan Son Nhut.

After landing, a staff car took Jerry Auth to Seventh Air Force headquarters while a jeep drove Bob Virtue the 25 miles (42 kilometers) back to Bien Hoa. Jerry’s plane was refueled and rearmed while he was briefed on Cambodia and the situation at the Provincial Capital of Kompong Thom. Within an hour he was airborne with a high-ranking Cambodian officer in his right seat.

The flying time for an O-2 from Tan Son Nhut direct to Kompong Thom was well over an hour, which was a long time to navigate in the dark with no lights on the ground, no radio fixes, and nothing but an obsolete map of an unfamiliar country. Night navigation was part of his job, though, and Jerry was very good at it. He flew directly to Kompong Thom and established radio contact with the ground commander. He was well out of radio range of any radio in South Vietnam, but he was in contact with some American gunships. They didn’t have the right radios to talk to the ground commander and could do nothing without target identification and positive target clearance. Working with the ground commander, Jerry could identify and mark the targets and he had the Cambodian clearance authority sitting right beside him. Jerry directed the fire of the gunships, which reportedly changed the course of the battle that night. A few weeks later, Seventh Air Force recommended Capt. Auth for the Silver Star for that mission.

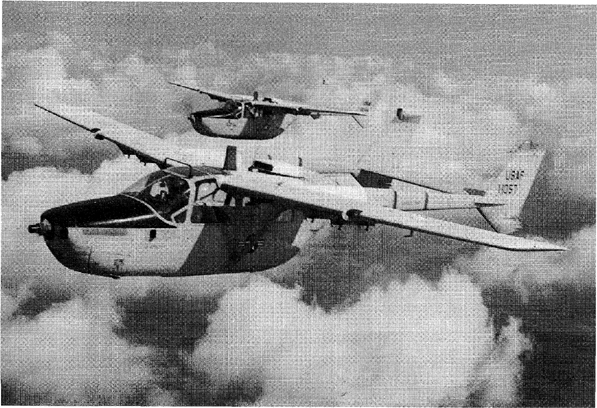

Two O-2A aircraft, minus external stores, fly in formation. Photo courtesy of Richard Roberds.

The next day, June 20, Dick Rheinhart and Dave Van Dyke took off early in the morning from Tay Ninh. Dick flew directly to Tan Son Nhut to fly the first OV-10 mission after being briefed and refueled. There, he also picked up an English-speaking Cambodian officer for his backseat. Dave headed for Bien Hoa to have a long-range (230 gallon) belly fuel tank installed. Lt. Lou Currier, who spoke French, was waiting for him. They were briefed by telephone and launched around noon to replace Dick Rheinhart. Jim Lester and the other four pilots went to Bien Hoa for installation of the 230-gallon fuel tanks and arrived at Tan Son Nhut in mid-afternoon.

Tan Son Nhut Air Base was the main airport at Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam. It was also the headquarters for all American military activity in Southeast Asia. This included Seventh Air Force, which controlled all USAF personnel and aircraft. After parking their planes, Jim and his pilots went directly to the Tactical Air Control Center where they were briefed by its director, Brig. Gen. Walter Galligan.

AC-130 “Spectre” gunship with an infrared sensor and low-light-level TV in the optical dome near the nose. Two 20mm Gatling guns are visible in front of the left main landing gear and the barrels of twin Bofors 40mm guns can be seen behind the landing gear. Ron Van Kirk collection.

According to Jim, General Galligan took out a six-foot strip of teleprinter paper that was plainly marked WHITE HOUSE. TOP SECRET. FOR YOUR EYES ONLY! He explained that the message contained Jim’s orders and his authorization to go into Cambodia and provide American air support to the Cambodian army. Air support could be obtained directly from Blue Chip, which was the radio call sign for the Tactical Air Control Center. Any targets in Cambodia had to be approved by a senior Cambodian official. There were several of them already at Tan Son Nhut and Blue Chip would obtain the necessary approval. Some of the officials might fly on the FAC missions.

The immediate problem in Cambodia was Kompong Thom.1 It was a provincial capital located about 93 miles (150 kilometers) north of Phnom Penh and it was under siege. The previous night, General Galligan had sent a single O-2 FAC (Capt. Jerry Auth) up there on very short notice and he was able to use some gunships to good effect. Unfortunately, Kompong Thom was well beyond normal radio range and the O-2 didn’t have a long-range high-frequency (HF) radio.2 The OV-10 did have an HF radio and would be able to talk to Blue Chip. The plan was to keep an OV-10 FAC over Kompong Thom twenty-four hours a day and provide whatever air support was necessary to break the siege.

General Galligan told Jim that his call sign would be Rustic and that all the Cambodian army call signs were Hotel followed by a two or three digit number or a word. He gave Jim a list of the known individual Cambodian call signs, their frequencies and the few maps that he had.

The general told Jim to use his outer office for mission planning until he could find him a better place. He reminded Jim that the entire operation was classified Top Secret and the instructions were coming directly from the White House. Very few people knew about the intentions of the United States to provide air support to Lon Nol and the Cambodian Army. The messages from the White House emphasized the need for secrecy.

Dick Rheinhart returned from the first mission and was able to brief Dave Van Dyke on the radio as Dave entered Cambodia to replace him. Capt. Roger Dodd was set up to fly the third mission early that evening. Roger’s OV-10 was fitted with the 230-gallon external fuel tank, twenty-eight rockets in four rocket pods, and two thousand rounds of ammunition for his guns. In his backseat, he carried Captain Chiik, a Cambodian Air Force pilot. Captain Chiik didn’t have target clearance authority, but he spoke passable English and could interpret conversations with the ground commanders. The OV-10 had a long-range HF radio, so target clearance would not be a problem.

The weather had turned terrible. It was the start of the monsoon season and a torrential rain was coming down. It was so bad that Jim Lester’s deputy, Dick Rheinhart, who had returned from the first mission, seriously considered canceling Roger’s mission and would have if it had not had such a high priority.

With all the water on the runway and the weight of the extra fuel tank, takeoff distance was much longer than Roger expected. Once airborne, he flew on instruments while tracking outbound on a radial of the Tan Son Nhut TACAN. That was a Tactical Air Navigation radio ground station that provided compass bearing and distance information to any aircraft receiving its signal. When the TACAN signal was lost at about 170 nautical miles, Roger kept flying using heading and time until he broke out of the clouds and could see the ground.

Roger got along fine with Captain Chiik, who was a good pilot and had an engaging sense of humor. His night navigation skills were weak, though, and he didn’t recognize much of his own country in the dark. They spent a considerable amount of time trying to locate themselves using the outdated maps they had been given. The weather made navigation even more difficult.

They finally made it to Kompong Thom, but without enough fuel to stay very long. Fortunately, it had been a quiet evening at Kompong Thom, probably due to the heavy rains and the work of Jerry Auth, Dick Rheinhart, and Dave Van Dyke. According to Roger, their presence was very welcome and reassuring to the troops on the ground.

The North American Rockwell OV-10 Bronco, built in 1968, was specifically designed for low altitude tactical support. It had two turboprop engines and could carry a variety of stores and ordnance on five stations beneath the belly and on two sponsons. The sponsons were airfoils that drooped down slightly from the bottom of the fuselage. Each sponson contained two M-60 machine guns and could hold one thousand rounds of 7.62mm ammunition for a total of two thousand rounds for all four guns. The standard load for long range missions was a large (230 gallon) fuel tank on the center station and two containers of rockets beneath each sponson. Each container held seven 2.75 inch FFARs (folding fin aerial rockets). Of the twenty-eight rockets, half of them had HE (high explosive) warheads while the other half were WP (white phosphorus) marking rockets called Willie Petes.

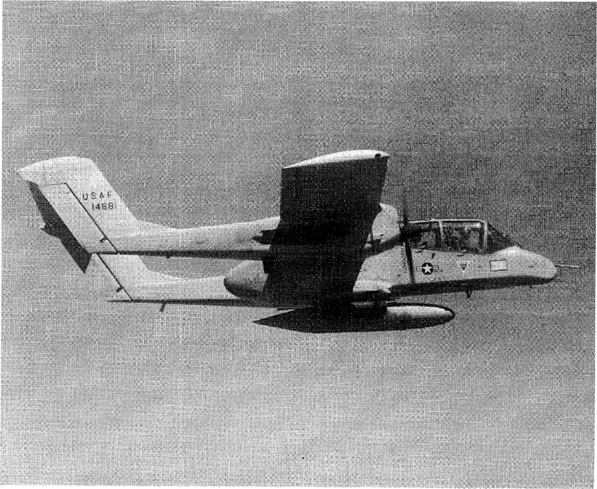

North American Rockwell OV-10 Bronco. Doug Aitken collection.

The tandem cockpit had ejection seats for two crewmen and featured superb visibility along with a total of five air-to-ground radios for communications. It had a large cargo compartment which could carry thirty-two hundred pounds of cargo or five paratroops. Its top speed was slightly over 300 knots (345 mph) and, carrying the 230-gallon fuel tank on the center station, it could stay airborne for nearly six hours.

The plane was fully aerobatic and stressed for eight positive and three negative Gs. It was armored and could absorb a lot of battle damage. It was also quite noisy. The North Vietnamese and Viet Cong called it “the bumblebee” and always knew when one was in the area. Most of the pilots scrounged (and treasured) U.S. Army helmets designed for helicopter pilots. They provided better protection and reduced the cockpit noise level considerably. Its other major defect was a total lack of any air conditioning. Since none of the four canopy hatches could be opened in flight, sitting under the Plexiglas canopy for five hours at low altitude was hot work.

All in all, it was rugged, easy to maintain, and an excellent plane for forward air control work.

Using aircraft to provide control of air support to ground forces was not a new concept. Airborne Forward Air Controllers (FACs) were used to some extent in World War II, but the technique wasn’t fully developed until jet fighters were introduced into combat during the Korean War. At low altitude, the jet fighters’ fuel consumption nearly doubled and they couldn’t stay there very long. At their slowest speed, they were going too fast for the pilots to see any details on the ground. They needed a Forward Air Controller (FAC) who could fly low, slow, and long and could identify the friendly positions and mark enemy locations for the jets. Most of the FAC’s work was in direct support of friendly forces and most of the time the friendlies were in direct contact with the enemy. That’s when they needed air support and a large part of the FAC’s job was to make sure the bombs went on the enemy and not on the friendly positions. In Korea, the North American AT-6 was used as a FAC aircraft. They were called Mosquitoes and the pilots were known as Mosquito pilots.

After the Korean War, President Dwight Eisenhower established a new list of “roles and missions” for the military services. Based on the experiences in Korea, it was agreed that there had to be a FAC present and in control anytime air-delivered ordnance was used anywhere near U.S. ground forces. The Air Force was adamant that a FAC controlling Air Force fighters had to be a fighter pilot himself. The Army argued that it was more important for the FAC to be an Army officer who understood ground warfare. On balance, the Army probably had the stronger argument, but the Air Force won and was committed to providing a fighter-qualified FAC to any Army unit needing close air support.

In Vietnam, the first FAC aircraft used was the Army Cessna L-19 Birddog, which the Air Force acquired and renamed the O-1. In military aviation parlance, L stands for “liaison” and O for “observation.” The O-1 served well, but it was limited on the number of radios and marking rockets it could carry. The OV-10 had been ordered, but wouldn’t be available until mid-1968, so the Air Force bought some twin-engined Cessna 337 Super Skymasters and designated them O-2As. The O-2A was a significant improvement over the O-1 and it also served well. It is described in detail in Chapter 5.

By 1970, FAC procedures were well established and FACs received formal training at the Air-Ground Operations School at Hurlburt Field in Florida. Rule number one, which came from the “Roles and Missions” doctrine of the armed services, was that if there were friendly forces anywhere in the area, no air-delivered ordnance would be dropped or shot without specific clearance from a FAC. The only exception was for the armed escorts of rescue helicopters. They could shoot at anything. Other than that, the FAC was in charge.

On a FAC mission, the first step was to establish contact with the friendly forces on the ground and learn exactly where they were. Contact was always on FM radio, which was the Army’s primary means of communication in the field. All FAC aircraft were FM-equipped, but few other Air Force aircraft had FM radios.

If the friendlies and the enemy were in contact and shooting at each other, it was called a TIC, troops-in-contact. This meant there was active combat in progress and friendly troops needed help. If it was available and there were no weather problems, they almost always received it, and this was when the FAC earned his pay. If the two sides were close enough to shoot at each other, they were also both close enough to feel the effects of any air-delivered munitions. The FAC’s job was to make sure that the friendly forces were not injured or killed in the process of attacking the enemy.

Locating the friendly forces was not always easy. In those days before global positioning satellite (GPS) systems, the troops on the ground seldom knew precisely where they were. The FAC had the same maps they had and sometimes the troops could be located by reference to a landmark that both could see. More often it was done by having the ground troops “pop smoke,” which meant igniting a smoke grenade. The FAC could see the smoke, even when it had to drift up through the jungle canopy, and establish the friendly positions based on compass direction and distance from the smoke.

Next, the ground troops would identify the location of the enemy by direction and distance from them. The FAC would go to that position and sometimes fire a white phosphorus (Willie Pete) smoke rocket that the friendly troops could see. The friendlies could thus correct the FAC’s knowledge of the location of the enemy.

Meanwhile, the FAC had requested air support and sometimes specified the ordnance he wanted. In South Vietnam, he did this through UHF radio to his controlling ground radio station, which used a land line (telephone) to relay the request to Blue Chip. In Cambodia, this didn’t work. The FAC was too far from any friendly radio station. Until that problem was solved, the FAC had to use long-range HF radio to talk to Blue Chip. Since only the OV-10 had HF radio and the radio was insecure (it could literally be heard all over the world), this limited operations considerably.

After approving the request, Blue Chip launched fighters or diverted them from some other activity. They were given the FAC’s call sign, radio frequency, and a rendezvous point. All Air Force planes used ultra-high frequency (UHF) radios for air-to-ground and air-to-air communication. Blue Chip would select an available frequency and make sure both the FAC and the fighters knew what it was. The rendezvous point was either a plainly recognizable landmark or a radial and distance from a navigation fix. At low altitude in Cambodia, the FAC couldn’t receive any navigation signals, but he had marked radials and distances from radio fixes on his map and he knew where they were. The fighters would check in on the frequency and start looking for the FAC. They were at high altitude and had to see the FAC in order to descend and work with him.

Since the FACs had to be identifiable, their aircraft were not camouflaged and the tops of the wings were painted white or light gray. In addition, the OV-10 had a special two-gallon oil tank that allowed a small amount of oil to be dribbled into the engine exhaust. A two-second burst of oil produced a nice white dash in the sky, which made the FAC easy to spot.

The FAC started by telling the fighters what was going on. Since they seldom had FM radios, they really didn’t know. They didn’t carry topographical maps, so target coordinates meant nothing to them. The FAC described the friendly and enemy positions and told them what their attack direction and pull-off heading would be. He did not allow the fighters to fly directly over the friendlies or even point their ordnance toward them. He told them the target elevation, what he knew of the wind situation on the ground, what they could expect in the way of enemy fire and the location of the nearest safe area in case they were hit and had to eject.

The FAC made sure they had him in sight and rolled in to mark the target with a Willie Pete rocket. The fighters acknowledged seeing the WP smoke and the FAC gave them any necessary corrections. Since the FACs got a lot of rocket practice, the most common instruction was, “Hit my smoke.” Next, the FAC switched to FM and asked for final confirmation on target location and told the troops on the ground that the ordnance was on its way. Back on UHF, the lead fighter called “Lead’s in, FAC’s in sight!” The FAC checked the fighter’s position and heading. If they were satisfactory, he said, “Lead, I have you in sight. You’re cleared hot.” He might also make a small correction to the target. “Put your first bomb 20 meters north of the smoke. Do not drop east of the smoke; that’s too close to the friendlies.”

Usually the fighters came in flights of two or sometimes three. The FAC cleared them one at a time for as many passes as it took to use all their ordnance or fuel. The code word for being out of ordnance was “Winchester.” A plane down to his minimum fuel reserve was “Bingo.” Sometimes the FAC would have them hold “high and dry” while he checked with the ground to find out if any adjustments were needed. During all this, the fighters and the FAC watched each other closely for any evidence of ground fire. Enemy fire from assault rifles was hard to spot in the daytime because there was not much of a muzzle flash. Machine gun fire could usually be seen because of the tracer bullets used to help the machine gunner aim his gun. If ground fire was seen, the FAC and the fighters would immediately shift their attention to it.

After the fighters were “Winchester,” the FAC would give them whatever BDA (bomb damage assessment) he or the ground commander was aware of. The FAC would thank them on behalf of the ground commander and clear them to return to base (RTB).

The FAC mission was undeniably dangerous. The FAC spent almost the entire flight within range of even small arms fire. Unless the enemy had some sophisticated aiming device, though, the FAC was not an easy target to hit. During rocket passes, he became easier to hit because he was usually lower than normal and the enemy gunner frequently had a good head-on or tail-on shot at him. Normally, though, the experienced enemy soldiers did nothing to attract the attention of the FAC. That would mean instant retaliation, particularly from the OV-10, which carried its own machine guns and HE rockets. Once the FAC started shooting WP rockets, the enemy would usually shoot back. They figured that if the FAC was marking a target, there was a fighter behind him with bombs or napalm and things couldn’t get any worse. They might as well shoot at the FAC.

Gunships were used widely throughout Southeast Asia. They were the product of someone’s brilliant idea that few thought would work. The original gunship was a modified C-47 called “Puff, the Magic Dragon.” Machine guns were mounted in the cabin and fired through holes cut in the left side of the fuselage. The pilot had a rudimentary gunsight rigged near his left shoulder and pointed out his left window. He would put the airplane in a left turn at a planned altitude and airspeed and adjust his bank to line the gunsight up with the target. He could fire all the machine guns with a trigger on his control column. The results were spectacular and someone described it as “a golden hose of bullets sweeping the target.” As long as he could identify the target, the pilot could put a stream of concentrated fire on it with remarkable accuracy. He could keep doing it for a long time, because he could carry a large amount of ammunition and fuel.

Once the Air Force learned how effective the gunships were, they began converting transports to gunships and improving their firepower and accuracy. Shadow was the call sign of an AC-119 gunship carrying four 7.62mm mini-gun pods. A later version, Stinger, also carried a 20mm Vulcan cannon. Spectre was an AC-130 that could carry a variety of weapons including mini-guns, 20mm cannon, 40mm cannon, and (in 1972) a 105mm howitzer.

Now that the initial missions were over and a schedule was established, Jim Lester could catch his breath and begin dealing with the organizational problems, of which there were many. Six planes and eight pilots could not maintain the coverage the White House wanted. Few of the Cambodian radio operators spoke English and none of the Rustic pilots spoke Cambodian. Relying on a few English-speaking Cambodians to fly as interpreters was, at best, a temporary solution. There had to be better maps than they presently had and both the pilots and the ground commanders had to be working from the same map. Communicating solely by HF radio was possible, but unsatisfactory. The Rustic pilots were collecting real time information about what was happening in Cambodia, but there was no organized method for dealing with it. The Rustics would need their own dedicated Intelligence section. Finally, flying Top Secret missions from Tan Son Nhut was not going to work. There was no OV-10 maintenance there, no separate living quarters, and no secure operational facilities.

In spite of the problems, the Rustics had started an operation that would last for three years and end only with the cessation of all American operations in Southeast Asia.