Operating the Rustic mission from Tan Son Nhut Air Base was never a good idea and it only lasted a few days. There was no maintenance or support for OV-10s and the entire operation was being run out of General Galligan’s outer office. The pilots were living in various parts of the officer’s quarters and the backseaters were spread out in the enlisted barracks. They were under strict orders to not tell anyone what they were doing and to never speak French in public. That was a little awkward as some of them welcomed the language practice that came from speaking French with each other.

Tan Son Nhut, being the headquarters for the entire U.S. Military Assistance Command in Vietnam, was scheduled to be the last U.S. facility to be closed and it was hopelessly crowded.

On the other hand, Bien Hoa Air Base was only about 25 miles (42 kilometers) north of Tan Son Nhut and had plenty of room. With Vietnamization in full swing, it was already in the process of shutting down. The Ranch Hand operation (C-123s spraying the defoliant Agent Orange) had gone out of business. The Third Tactical Fighter Wing had traded in its F-100s for A-37s and they, in turn, were being gradually turned over to the Vietnamese Air Force. The most active organization on the base was the Nineteenth Tactical Air Support Squadron (TASS).

The Nineteenth TASS was a squadron, but it was actually bigger than most wings. It owned around 150 OV-10s and O-2s plus the pilots to fly them and the mechanics to maintain them. All of the Rustics and their airplanes were technically assigned to the Nineteenth TASS. The reason the TASS didn’t look very big was because they kept the planes and crews at twenty-two different FOLs (forward operating locations) where they were supporting American, Vietnamese, Thai, Korean, and Australian army units. They only kept eight or nine planes at Bien Hoa, which they used for training or as “loaners” for aircraft brought to Bien Hoa for inspection or serious maintenance. The decision to move the Rustics to Bien Hoa was an obvious one and it was done with no break in the mission schedule. The pilots and backseaters merely loaded their belongings into the OV-10 cargo compartment, flew a mission, and landed at Bien Hoa.

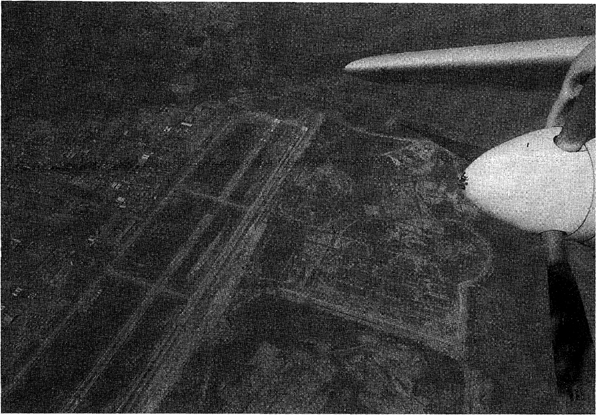

Bien Hoa Air Base. Picture was taken on a maintenance test flight to check the propeller feathering system. Richard Wood collection.

In the military, organizations are sometimes thrown together hurriedly to meet a need without much regard for logic. The Rustic organization at Bien Hoa was like that.

In Southeast Asia, the entire U.S. effort was under the command of COMUSMACV, pronounced “Comus-Mac-Vee,” which stood for Commander, United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. It was commanded by General Westmoreland and later, General Abrams, and was located at Saigon.

U.S. Air Force support was provided by Seventh Air Force located at Tan Son Nhut Air Base at Saigon. Seventh Air Force was part of Pacific Air Forces (PACAF) headquartered in Hawaii. PACAF, while part of the U.S. Air Force, was under the operational control of CINCPAC (Commander in Chief, Pacific), which was also headquartered in Hawaii. CINCPAC was a joint services command traditionally headed by a Navy admiral. On top of all this, of course, were the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

This organizational structure had existed since the United States entered the conflict in 1965 and by 1970 it was pretty well “set in concrete.” Historians point out that one of the United States’ major problems in Vietnam was the way the war was managed, or mismanaged, depending on your views. Authority could come from several different directions, but it was hard to establish responsibility.

Into this morass came the Rustics. Their mission orders came directly from the president and bypassed all levels of command between him and COMUSMACV. In Vietnam, Seventh Air Force owned all FAC assets and managed them through the 504th Tactical Air Support Group at Cam Ranh Bay. The 504th had five Tactical Air Support Squadrons at Bien Hoa, Da Nang, Pleiku, and Binh Thuy in South Vietnam and Nakhon Phanom in Thailand. These squadrons were numbered Nineteen through Twenty-three respectively. Shortly after the formation of the Rustics, the Twenty-first TASS at Pleiku moved to Phan Rang and the Twenty-second TASS at Binh Thuy moved to Bien Hoa. Operational control was from the Seventh Air Force Tactical Air Control Center (TACC) and the Direct Air Support Centers (DASC) in each of the four Corps areas in South Vietnam and at Nakhon Phanom. At first, a Task Force was formed at III DASC under the command of Col. Perry Dahl. This consisted of the Rustic, Sundog, and Tilly FACs. The Sundogs and Tillys both flew O-2s and were established FAC operations in the South Vietnam delta region. They were close enough to begin operating immediately in southern Cambodia. In February 1971, the name of the task force was changed to Nineteenth TASS Task Force, but the operational control remained the same. The Nineteenth TASS was primarily an administrative unit that owned and maintained airplanes and kept track of the people and facilities; but not the mission. That belonged to the task force and their instructions came directly from Seventh TACC. Operationally, the DASCs were bypassed as none of them provided support to Cambodia. At the Nineteenth TASS and task force level, the organization worked quite well. The Nineteenth TASS provided outstanding support and the Rustics took their marching orders directly from Seventh Air Force TACC. Airborne, they talked directly with “Blue Chip,” the Seventh Air Force Command Center.

Some of the original OV-10 Rustics at Bien Hoa, November, 1970. Back row, left to right: Joe Vaillancourt, Doug Hellwig, Don Ellis, Gil Bellefeuille, Paul Riehl, Mike Wilson, Dick Wood, Jim Lester (Commander), Jim Hetherington, Bob Burgoyne, Chuck Manuel. Front row: Don Brooks, George Brower, Clint Murphy, Bob Paradis, Ron Dandeneau, Hank Keese, Greg Freix, A1 Metcalf, Jerry Dufresne. Joe Vaillancourt collection.

When the Rustics moved to Ubon, Thailand, in 1971, they became Operating Location 1 (OL-1) of the Twenty-third TASS at Nakhon Phanom. Operationally they were still controlled by Blue Chip in Saigon. That organization also worked well.

When problems occurred, they were usually at the COMUSMACV—Seventh Air Force level at Saigon. Shortly after the move to Bien Hoa, Jim Lester returned to Tan Son Nhut to brief both General Clay, the new commander of Seventh Air Force, and General Abrams, COMUSMACV.

General Clay was briefed first and asked Jim if he had any problems.

“Yes, we do. I was out yesterday near Kompong Speu and the ground commander said that he had a TIC (troops in contact) about 10 klicks down the road and he needed an airstrike. I flew over there and I could see people running around and shooting, but I couldn’t tell the good guys from the bad guys. The only radio they had was back with the commander and they didn’t have any smoke grenades to identify themselves. I didn’t dare put in an airstrike. If we can’t identify the friendlies, we can’t help them.”

“Did you tell anybody about this?”

“General, I’ve put this problem in the DISUM several times.”

“What’s a DISUM?”

“That’s your daily intelligence summary.”

“Well, who gets that?”

“Your Intell people and your Tactical Air Control Center gets it.”

Jim felt like he was talking to a child. General Clay was brand new on the job and he had no idea how the Rustics were organized or how the system worked. Every officer newly assigned to Vietnam went through a period of disbelief at how things were run.

“Well,” he said, “we’re going over and brief COMUSMACV. We will take care of any of your problems.”

Jim and General Clay went into the command center where there were about fifteen generals sitting around a long table with General Abrams at the head. Jim gave him the problem of communications with the ground and identifying friendly forces.

“I thought,” General Abrams said, “that we sent them four hundred cases of smoke grenades.”

“Yes, sir. We sure did. Those went to Phnom Penh a month ago. I have no idea what happened to them.” General Abrams and his staff were right on top of it. They knew exactly what was going on. At the end of it, General Abrams assigned an Army major to move to Bien Hoa and work directly with Jim to resolve those problems when they occurred.

So now Jim had an Army officer on his staff who could make sure the Cambodian Army had the equipment it needed to work with the Rustics. The Army major fit in well with the Rustics, particularly since he brought ten boxes of sirloin steaks with him to Bien Hoa. He obviously understood the supply system.

In the fine print of the daily Top Secret Eyes Only messages from the White House, there was an absolute restriction against landing in Cambodia, anytime, for any purpose. This was strictly political and meant to support President Nixon’s claim that there were no American forces on the ground in Cambodia. Nixon felt he could justify the fact that the Rustics were flying over Cambodia, but it would be hard to explain an American combat plane and pilot on the ground. Being on the other side of the world and fighting a war, the Rustics were probably less interested in political happenings in the States than they should have been. This restriction lasted for about a week and was violated about the time the Rustics moved to Bien Hoa.

In late June, Don Shinafelt, an Issue FAC normally stationed at Tay Ninh, returned to Bien Hoa from a week’s R&R (rest and recuperation) in Australia. He checked into the Nineteenth TASS and found that all of the Tay Ninh pilots were now flying out of Bien Hoa as Rustics. His personal belongings were on a truck somewhere between Tay Ninh and Bien Hoa. He had only his civilian R&R clothes and one set of flying gear, which he had left with the Nineteenth TASS. The next day, he was flying his first mission as a Rustic. It was an orientation flight for him and he had a Cambodian backseater to show him the territory.

We were over the Tonle Sap when I heard the Rustic that was supposed to relieve me call and say he couldn’t get through the thunderstorms that were lined up along the border. I tried to go back to Bien Hoa, but I couldn’t get through them either. The Cambodian in the backseat was urging me to land at Phnom Penh. His family was there and he hadn’t seen them for quite a while. I really didn’t have much choice.

After landing in the rain and parking the plane, the backseater got us a ride to town and dropped me at a hotel. He was going to pick me up in the morning. Some Americans in civilian clothes got me some food and a bed for the night. The next morning, we went back out to the airport, fired up the plane and flew it uneventfully to Bien Hoa.

Unless they absolutely had to, the Rustics didn’t regularly land at Phnom Penh until 1973, when permission was officially granted to refuel there. As a practical matter, no pilot in his right mind was going to eject and let the plane crash if he could land it safely at Phnom Penh. The Rustics had an open invitation from their Cambodian Air Force friends to land there anytime. When they needed to, they did.

As soon as the Rustics settled in at Bien Hoa, I became Rustic 11 and started flying with them. I had been in Vietnam since mid-March and already had a full-time job as chief of safety for the Nineteenth TASS. I was a fully qualified OV-10 FAC, though, and I could schedule myself to fly a Rustic mission nearly every other day. I also averaged about three OV-10 maintenance test flights each week. They only lasted forty-five minutes or so and were easy to fit into the schedule.

Becoming a Rustic was not a problem. Jim Lester and I had been through OV-10 school together and we were good friends. He needed pilots and was happy to have me, even part time.

The commander of the Nineteenth TASS was Lt. Col. Bill Morton, who had also been with us at OV-10 school. Bill was in his mid-fifties, thin as a rail and topped by a steel gray brush cut. He hadn’t flown actively for several years, but he loved the OV-10 and was a very good pilot. He few several Rustic missions as Rustic 10.

Bill once told me that he had the distinction of being the senior ranking lieutenant colonel in the entire U.S. Air Force. He had been passed over five or six times for promotion to full colonel, a situation that would encourage most people to retire. Bill loved what he was doing, though, and intended to hang around for as long as the Air Force would let him.

Being passed over for colonel was no disgrace as the promotion opportunity for that rank was something less than 20 percent. A lot of really good officers didn’t make it, Bill Morton among them. Based on its size, the Nineteenth TASS should have had a full colonel for a commander. They were lucky to have Bill.

That camaraderie among us was very helpful. The Nineteenth TASS maintained the Rustic planes and took care of all the personnel matters involving the pilots and backseaters. Bill made sure of that support and Jim was free to concentrate strictly on the mission. Occasionally, the Rustics would lose a mission due to weather, but since the TASS had spare aircraft, they would never lose one to maintenance or aircraft availability. As a maintenance test pilot, I kept the spares ready and became the primary recoverer of aircraft landed at Phnom Penh. The OV-10 cargo compartment could carry tools, parts, or an engine for either the OV-10 or the O-2 and the backseat could carry a mechanic. I made the Phnom Penh recovery trip about six times.

The move to Bien Hoa did not make everyone happy. Like the camel sticking its nose into the Arab’s tent, the Nineteenth TASS and the Rustics were beginning to take over Bien Hoa. Within a few weeks, the TASS had moved into a vacated Third TFW (Tactical Fighter Wing) squadron building, many of their maintenance hangars and an aircraft parking ramp in prime real estate. The Rustics moved their pilots and backseaters into a vacant fighter squadron hooch (complete with bar) and took over part of the Third TFW Operations building for their intelligence section.

The base commander (who was also the commander of the Third TFW) did not like the Nineteenth TASS, the FACs, or their airplanes. In retrospect, his dislike was somewhat understandable. The Nineteenth TASS did not look or act like a real Air Force organization. Most of the FACs and mechanics were based at army forward operating locations and were living the same way the army grunts lived. There were no barbers out there and shaving was optional. The FACs learned that the official Air Force flying suits did not hold up well in the field. They usually wore whatever the army was wearing, which varied from camouflaged fatigues to Australian shorts and bush hats. Flying long missions at low altitude in a hot humid climate was a hot, smelly business and laundry services were not always available. The FACs based with the First Cavalry Division at Quan Loi were recognizable at several feet because their clothes all had a peculiar reddish tinge. Quan Loi had a unique red mud that attached itself to everything and would not completely wash out.

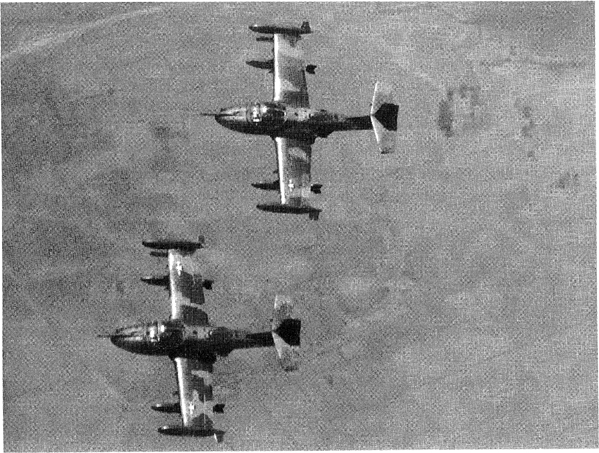

Two A-37s from Bien Hoa. These were the Rustics’ favorite fighters for close air support. Doug Aitken collection.

The planes were even worse. Few of the FOLs had paved runways. The FACs were operating from dirt strips occasionally smoothed with the army’s tar-like version of instant asphalt. That stuff stuck to the planes like Quan Loi mud. Since water had to be trucked in, nobody wasted it on washing the airplanes.

In addition to being dirty, planes based at FOLs tended to pick up unusual paint jobs and nose artwork, usually in the colors of the army unit. The fuselage frequently acquired a large decal reflecting the unit’s coat of arms. The Air Force had its own paint scheme for its airplanes and any variations or additions were strictly prohibited. Those planes had to be kept hidden from Air Force inspectors. The FACs always disclaimed responsibility for this and swore that the army grunts (who loved the FACs for their air support) would sneak up on a plane at night and give it a free paint job. They did the same thing to their own helicopters and, to them, it was a matter of pride. As far as the grunts were concerned, those FACs and airplanes were theirs. This suited the FACs, because after a few weeks at an FOL, they tended to identify more with the Army than the Air Force.

On any given day, the Nineteenth TASS probably had four or five FACs and their airplanes visiting from one of its twenty-two FOLs. The planes were brought in for major maintenance or inspection and the FACs were there on a shopping trip to pick up anything needed by anyone back at the FOL. The visiting FACs would stay overnight and always treat themselves to a few drinks and a steak dinner at the Bien Hoa Officers Club—wearing whatever they flew in with.

This constant presence of dirty airplanes with illegal paint jobs and ratty-looking pilots was probably responsible for the wing commander’s anti-FAC attitude. In addition, he was losing authority, real estate, and facilities to the Rustics and the Nineteenth TASS. His job (as he saw it) was to close the base down and give it back to the Vietnamese. Here he had this outfit that was growing like a weed and looking seriously at taking over his personal office, quarters, and staff car. What really annoyed him was that whatever the Rustics were doing, it was Top Secret and he wasn’t allowed to know.

The last straw came when he found out that the Rustic pilots and their enlisted backseaters were all living in the same hooch and drinking at the same bar. Officers and enlisted men living in the same building? Absolutely not! Since he was a full colonel and neither the Rustics nor the Nineteenth TASS had one of those, the confrontations with Jim Lester and Bill Morton got a bit heated. About two weeks after the Rustics arrived, he ordered Jim Lester to move the enlisted people out of the Rustic hooch and put them in the enlisted barracks. That would defeat the Top Secret security Jim was trying to maintain among the Rustics, but the wing commander wasn’t buying that argument.

“I said, ‘Yes, sir.’ Then I called General Galligan at Seventh Air Force and said, ‘I’m having to move my enlisted people out of the Rustic hooch.’ He asked me why I was doing that. I told him I was ordered to do it.

“ ‘Who ordered you?’

“ ‘The Wing Commander.’

“ ‘That son of a bitch. That’s none of his business. Don’t move them out. I’ll talk to him.’ ”

Meanwhile, the wing commander went to Col. Perry Dahl, Jim’s immediate superior and told him to get rid of Jim. He didn’t want him on his base.

“I told Perry that he might as well do that and get someone to replace me who either outranked him or could get along with him. Perry told me to quit worrying. He’d take care of it.”

A week later, the wing commander was reassigned as an assistant to General Galligan at Tan Son Nhut. Two weeks later, armed with a new security clearance, he was back at Bien Hoa to be briefed on the Rustic operation. Afterward he told Jim Lester what a great job the Rustics were doing and went back to Tan Son Nhut. Jim already knew they were doing a great job. He also knew that the Rustics were emerging as the most active military operation in the entire theater. They would get whatever support they needed.

Throughout the late summer and fall of 1970, the Rustic operation continued to grow. At Tan Son Nhut, there had been only eight FACs, six aircraft, and a handful of backseaters. In four months, the operation had grown to fifty-two aircraft, seventy FACs, twenty interpreters, ten radio operators, and ten intelligence specialists. Considering that the Nineteenth TASS was handling all the logistics and maintenance and still operating FAC detachments at several FOLs, the total operation was one of the largest USAF operations in the war.

Initially, FACs came from other III Corps locations to become Rustics and the Nineteenth TASS juggled its aircraft resources to support them. This worked for a couple of months, but eventually the Nineteenth TASS’s parent group (504th Tactical Air Support Group at Cam Ranh Bay Air Base) began sending in FACs and aircraft from all over South Vietnam and Thailand. The Rustics had top priority on resources and growth sometimes happened over night. At one time, the Seventh Air Force Director of the Tactical Air Control Center told Jim that he wanted another FAC available over Cambodia twenty-four hours a day in addition to the ones they already had.

I told him that would take another six airplanes and at least eight more pilots. He picked up the phone and called a two-star general—I don’t know who—and told him to move six planes and crews to the Rustic operation at Bien Hoa. I could tell from the conversation that the two-star didn’t like that at all. The director told him that he didn’t care whether he liked it or not. He could either do it or meet him upstairs to discuss it with the four-star. The planes and crews arrived the next day.

One of the first things Jim Lester did at Bien Hoa was to set up a FAC training school for Cambodian radio operators and pilots. Cambodia would send in small groups of Cambodians to spend a few weeks with the Rustics and learn something about the FAC business. Claude Newland (Rustic 19) organized some of the early training courses. Since few of the students spoke English, the course was taught mostly in French by the backseaters.

One of the students in the first class in September 1970, was one of Cambodia’s most experienced fighter pilots, Capt. Kohn Om.1 In the late 1950s, Om was sent to France to be trained as a pilot by the French Air Force. There, he learned English out of a book, Fundamentals of American English, which he carried with him at all times. Back in Cambodia in 1964, he was taught to fly the Russian MiG 15 and MiG 17 by an instructor who spoke only Russian. At the Rustic FAC school at Bien Hoa, Om flew as a backseater in the OV-10 almost every day and got to know most of the pilots. As part of the course, the Rustics provided handout material translated into French on radio procedures, rules of engagement, weapon selection, and a host of other subjects. Kohn Om took all of this material back to Cambodia and set up a FAC school there for young NCOs.

Claude Neland (Rustic 19) with four Cambodian officers he trained at the Rustic FAC school at Bien Hoa, October 1970. Left to right: Lieutenant Huot, Captain Kohn Oum, Captain Ouem, Lieutenant Sophan. Kohn Om was an experienced Cambodian Air Force fighter pilot who worked with the Rustics throughout their existence. Note OV-10 in the background with belly fuel tank, sponson machine guns, and rocket pod. Claude G. Newland collection.

Om had a standing invitation to return to Bien Hoa when he could and lecture to any FAC class that was in session there. When Om was flying a Cambodian fighter, he would always tune the Rustic frequency to talk to the pilots and backseaters he knew and find out if they had any targets for him.

During their early flights in the central region of Cambodia, the Rustics met another Cambodian officer. They were regularly in contact with Hotel 303. This was Col. Lieou Phin Oum, then a major. In the next six months he would be promoted twice and, to avoid confusion, he will be referred to as Colonel Oum.

Colonel Oum turned out to be Cambodia’s best military leader. Oum was originally trained in both the United States and Cambodia as an Air Force communications specialist. He later attended senior military schools and became one of the Cambodian Army’s most dependable commanders. He was very well educated and his command of English was almost perfect. Regardless of the situation, he was unfailingly courteous and polite and all the Rustics became familiar with his somewhat clipped and formal manner of speech.

“Rustic [his pronunciation was closer to Roostic] this-is-Hotel-Tree-Oh-Tree-how-are-you-today-sur?” During radio conversations, Oum would provide the Rustics with current estimates of enemy strength, location, and plans. These were invariably accurate. For several months, the Rustics knew him only as a voice on the radio and didn’t realize he was a senior officer until he visited the Rustics at Bien Hoa.

Life at Bien Hoa was not bad. It had most of the conveniences of any large Air Force base including a base exchange, post office, library, chapel, swimming pool (left over from the French) officers club, enlisted club, and mess hall. The toilets flushed, the showers worked, the officers’ hooches were air-conditioned, and the hooch maids took care of the laundry. After a sweaty day of flying, it was nice to come home to an air conditioned room, a shower, clean clothes, and a beer. Most of the FACs weren’t used to such luxury, but they rapidly adjusted. They started wearing official USAF flying suits and looking like real Air Force pilots. The Nineteenth TASS kept their airplanes clean and painted the way they were supposed to be painted.

Among the drawbacks were the regular rocket attacks on Bien Hoa. These were Russian-made 122mm rockets that packed about 30 pounds of high explosives. They stood a little over six feet tall and were about eight inches in diameter. The rockets were all transported down the Ho Chi Minh trail and hand-carried to launch positions near Bien Hoa.

The typical rocket attack occurred in the wee hours of the morning about twice a week. It consisted of five to ten rockets fired very rapidly. The entire attack seldom lasted more than a minute or two, although it seemed longer.

It was always assumed that the targets were the fuel storage tanks, the bomb dump, or the aircraft, and that the mess halls and hooches were relatively secure. Unfortunately, the aiming and launching methods were very primitive and the rockets might hit anything. Nothing was safe. Americans learned to appreciate what the British must have felt during the V-2 rocket bombardment of London in World War II.

Each building had an area reinforced and sandbagged and designated as the rocket shelter. If you were suddenly aroused from a sound sleep by the explosion of a rocket (followed by the rocket attack warning siren; the normal sequence) and you knew the attack wasn’t going to last very long, running for the shelter didn’t make much sense. Most just grabbed their flak jacket and helmet and rolled under the bed. The buildings were all sandbagged to a few feet above floor level so this offered some protection from anything but a direct hit.

One of the daily pleasantries enjoyed by the Rustics at Bien Hoa was the company of their mascot, “Missue.” Missue was a small, cute, intelligent, and well-behaved dog of uncertain breed. She was originally acquired by the Issue FACs at Tay Ninh and was brought by truck to Bien Hoa when the Issue FACs became Rustics. Her name was a contraction of “Miss Issue.” She lived in the Rustic hooch and had the full run of that building and the Operations building. Jim Gabel, the Rustic Intelligence Officer, was particularly fond of Missue.

One of the worst things that happened in 1970 during our Christmas “vacation” was the disappearance of Missue. I was probably the last one to see her on New Year’s Eve. As I was coming home from work about 2100, I met her going toward the Ops building. It didn’t take much coaxing to get her to follow me back to my room, where I treated her to a jar of dried beef. It was my birthday and I figured someone should help me celebrate.

After she disappeared, we all felt that as plump and well-fed as she was, she probably ended up downtown as someone’s New Year meal. Nineteen-seventy had been the year of the dog, so she was reasonably safe. With the dawn of 1971, though, her immunity was gone.2

By January 5, I had given up hope of seeing her again. We had another dog named Candy, but she just couldn’t replace Missue with any of us.

Then on January 10, Missue reappeared. She just walked up to the door of the Ops building, apparently very happy to be back. She was much thinner and smelled like she had spent the entire time in a sewer. After cruising the building and saying hello to everyone, she settled down on her usual place on the floor of the briefing room. The sewer smell was more than I could stand so I took her to the hooch where I washed her in the shower with some Prell shampoo. She wasn’t too happy about that, but perked up when I fed her the steak I had thawed for her.

The message, “Missue’s back,” went out by radio to the Rustics already flying that day and was passed to our Cambodian friends who had been to Bien Hoa, knew her, and knew she was missing. It is amazing how much love can be lavished on a dumb animal. She was a surrogate for all the wives, girlfriends, and families left back home.

“Missue.” The OV-10 Rustics’ mascot. Doug Aitken collection.

At Bien Hoa, the Rustics acquired an extra backseater. Maj. Robert (Doc) Thomas was a flight surgeon at the Bien Hoa medical facility. Although he was assigned as a doctor, he spent as much time as possible with the various units on the base, particularly the Rustics. The two French-speaking Rustic pilots, Lou Currier and Hank Keese, frequently had an empty backseat that Doc Thomas could fill. The Rustics figured that having their own doctor available was a pretty good idea, so they gave him his own call sign, Rustic X-Ray. That seemed appropriate. As a result of his flights with the Rustics, Doc Thomas became the local arms and munitions merchant.

It all started as the result of one mission with Hank Keese. I think we were flying over Kompong Chhnang, but I was always lost. We saw a well-armed guerrilla unit chasing Cambodian Army soldiers who appeared to have only a few Enfield carbines, probably of World War I vintage. Our government was not supplying Cambodia with arms, and they obviously needed help.

That night, I was at the First Cav. [U.S. Army First Cavalry] area where I saw them getting ready to destroy a pile of captured enemy weapons. I told them that we had some allies who were fighting without any reliable weapons, and that it would be a real payback to the Viet Cong if their weapons were sent back into the field to be used against them and the NVA. The Cav liked that idea and pretty soon the word spread all the way to their headquarters at An Loc.

I started getting jeeploads of weapons, which I stored in my room. My roommate moved out. It became a joke in the Rash hooch where I lived that if we were hit by a rocket, the secondaries would go off for a week. I’m not sure they were joking. The Navy SEAL team, who usually drank with us, brought in their captured RPGs (rocket-propelled grenades), and the Green Beret outfit contributed some captured explosives.

It just kept piling up and I wasn’t sure what to do with it. Then we got word that an Air Force inspection team was coming and we had to do something. Through the Rustics, we got word to Col. Oum and he arranged for a Cambodian C-47 to land at Bien Hoa and pick up the pallets of arms and munitions. That was pretty hectic and probably illegal, but every now and then we did something right.

Actually, there was another small source of arms for the Cambodians. Bien Hoa was one of the major aerial ports of entry and exit; the others being Da Nang, Cam Ranh Bay, and Tan Son Nhut. Each day, “Freedom Birds” (commercially chartered transports) would arrive daily to take U.S. personnel of all services back to the United States. Preboarding procedures included exchanging all the military scrip (called Mickey Mouse money) for dollars and a thorough inspection for arms and ammunition being taken home as souvenirs. Since no one wanted to be pulled off the flight to explain why he had an AK-47 in his luggage, the passengers tended to “donate” the weapons before they were discovered and taken from them.

Since the Rustic Intell shop had become the senior intelligence organization on the base, all of these weapons were turned over to them for “examination and proper disposal.” To the Rustics, this meant shipping them to Cambodia. The Cambodians attending the Rustic FAC school were delighted to handle the transportation details. The souvenir take from seven flights per week and three hundred passengers per flight could be quite substantial.

Just as the FACs had identified with the U.S. Army units they were supporting, they now identified with the Cambodians.