In July 1971, Tom Adams’s tour was up and Lt. Col. Walter Arellano took command of the Rustics.

At Bien Hoa, things were changing rapidly. The process of Vietnamization was accelerating and Bien Hoa was going to be returned to the Vietnamese. By mid-August, there was serious talk about cut backs and consolidation. Other units could cut back their mission and consolidate their operations, but politically, the Rustics were still committed to supporting Cambodia. There would be no cutback. Chenla II began in August and the Rustics were as busy as ever. Walt Arellano was given the task of developing a plan to move out of Bien Hoa and continue to provide full Cambodian support while doing so.

The closing of a base the size of Bien Hoa while there was still a war to be fought was chaotic. There were Vietnamese to be trained to fly the airplanes they would be given, critical supplies to be packed and shipped back as cargo, personnel to be transferred or (they hoped) sent back to the United States—it was a big mess. You checked your mailbox at the post office every day because there was no assurance the post office would be there tomorrow. It was obvious that the Rustics could not stay at Bien Hoa under any conditions. Shortly there would be no fuel, no munitions, no food, and no support.

An early plan was to move the Rustics to Tan Son Nhut in Saigon and let them operate from there. That was unacceptable for the same reasons the Rustics left Tan Son Nhut a year earlier. There was no room and no support for the aircraft. In September, it looked like the Rustic OV-10s would move to Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base in Thailand.

Ubon was one of six air bases in Thailand used by the United States Air Force.1 It had plenty of room and could support the Rustic OV-10 operation. It was located due North of Phnom Penh and the flying time from Ubon to Phnom Penh was roughly one third greater than it was from Bien Hoa. Considering the OV-10’s endurance with the big belly tank, this still gave the Rustics about three and a half hours of useful time in the target area.

The question was what to do with the Rustic O-2s. There was talk of moving them to the Mekong delta region of South Vietnam and having them continue flying as Tilly or Sundog FACs. The Tilly and Sundog FACs had been assigned to the Nineteenth TASS Task Force (which included the Rustics), and they also came under Walt Arellano’s command. They had been flying some of the Cambodian missions from the delta region for nearly a year. This was a span-of-control problem for Walt and he spent a lot of his time traveling among the three bases.

Fortunately, he had some very strong leaders at each location. Major Womack ran the Sundogs at Tan Son Nhut and Major Perret had the Tillys at Binh Thuy. At Bien Hoa, he had Major Clifford for the Rustic OV-10s and Major Roberds for the Rustic O-2s. All were experienced and knew what had to be done and how to do it.

There were several problems with moving the O-2s to Ubon. Under the U.S. Status of Forces Agreement2 (SOFA) with Thailand, there was a limit to the number of U.S. personnel who could be stationed there. The agreement could accommodate most of the OV-10 operation, but the O-2 operation would put them well over the limit. Also, the added flight time from Ubon to central Cambodia significantly reduced the O-2’s effective mission time.

The final decision was to move the OV-10 Rustics to Ubon. The Nineteenth TASS would move to Phan Rang Air Base and be combined with the Twenty-first TASS where they would set up an O-2 training program. The Rustic OV-10 pilots were assigned to the Twenty-first TASS for a short time until the Status of Forces Agreement with Thailand could be straightened out. Then, the Rustic OV-10 pilots were officially assigned to Ubon as FOL #1 of the Twenty-third TASS at Nakhon Phanom. The Rustic O-2 pilots were reassigned to the new TASS at Phan Rang, the Sundogs at Tan Son Nhut or the Tillys at Binh Thuy. The Night Rustic O-2 operation itself was deactivated.

The Night Rustics only existed for fourteen months, but that small group of pilots literally wrote the book on night FAC operations in direct support of ground commanders. Because the mission was highly classified and there were so few people involved, the Night Rustics never received the recognition they deserved. Flying at low altitude at night over a combat zone where there were no lights on the ground and no navigation aids took a special kind of bravery. Even if there was no enemy activity, that was an inherently dangerous way to operate an airplane. The Night Rustics earned the respect of everyone familiar with the Rustic operation.

As part of Vietnamization, Walt Arellano had been given a few other tasks that had nothing to do with the Rustics. He was frequently out of the country and Maj. Les Gibson became the Rustics’ acting commander for the purpose of moving to Ubon. He became the official Rustic commander after they had arrived at Ubon.

One result of the move to Ubon was a reduction in the number of backseaters. In addition to the limitations on personnel in Thailand, most of the original group of backseaters had served their tour and some were serving on voluntary tour extensions. The Rustics only took nine backseaters with them to Ubon. These were the newest ones who had the most time remaining on their tours. By the time their tour was up, the Rustics expected to be getting new OV-10 pilots who had completed French language school.3

Les Gibson had several meetings at Seventh Air Force and made two trips to Ubon to coordinate the move with the host unit, the Eighth Tactical Fighter Wing. He arranged for hooches, maintenance hangars, flight operations buildings, and parking ramp space for the aircraft. Because the OV-10 cadre slightly exceeded the Thailand personnel limits, some personnel were technically still assigned to the Twenty-first TASS at Phan Rang, but were on temporary duty (TDY) orders to Ubon. That was one way of circumventing the personnel limitation of the SOFA.

The Rustic pilots and backseaters moved the airplanes. They could fit all of their personal belongings in the cargo compartment, fly a mission over Cambodia and land at Ubon. For the rest of the move, Les Gibson used five C-130s to move all the support people and all the maintenance, supply, office, and intelligence equipment. Some of the C-130s made more than one trip and the move was essentially completed in two days.

Missue, the Rustic mascot, was put in a box and loaded onto a C-130. She did not like that at all and ended up riding on the flight deck and making friends with the crew.

When the Rustics were designated as a Nineteenth TASS Task Force, they acquired their own chief of maintenance, Senior M. Sgt. Don Corrie. He turned out to be an essential element in the move.

Since Bien Hoa was closing, almost everything there was up for grabs, so to speak. Don Corrie loaded all the spare parts he could find for the OV-10s plus all the bunk beds, foot lockers, wall lockers, typewriters, lawnmowers, and M-16 assault rifles that no one else seemed to want. The Rustics arrived at Ubon as one of the best equipped units on the base. Most of the M-16s were eventually given to the Cambodians; another illegal arms transaction that would have made Doc Thomas (Rustic X-Ray) proud.

At Ubon, the Rustics were officially designated as Operating Location #1 (OL-1) of the Twenty-third TASS at Nakhon Phanom RTAFB. Nakhon Phanom (also known as NKP or sometimes “Naked Fanny” or “Naked Phantom” in honor of their special forces operations) was on the Laotian border and about a forty-five-minute flight due north of Ubon. The Twenty-third TASS owned the Nail FACs whose mission was almost entirely in Laos over the Ho Chi Minh trail. The Rustics at Ubon were still under the direct control of Blue Chip at Seventh Air Force, so this really wasn’t much of a change in their organizational structure. They were getting the same administrative support from the Twenty-third TASS that they had from the Nineteenth TASS at Bien Hoa.

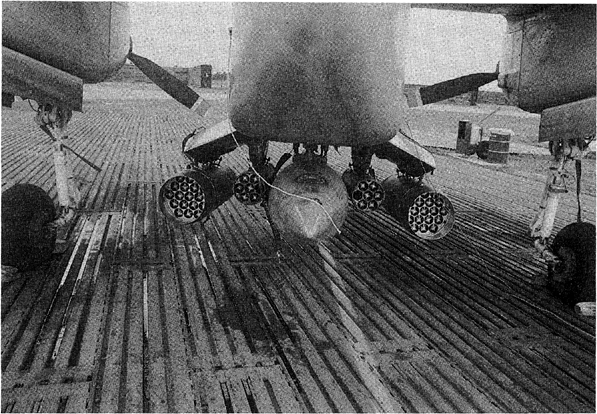

The munitions load for the OV-10 at Ubon was slightly different. It carried the same 230-gallon fuel tank on the center station along with the four M-60 machine guns in the sponsons. On the outboard sponson stations, though, it carried LAU-3 rocket pods each loaded with nineteen HE rockets. The inboard stations carried LAU-59 pods with seven rockets each. One pod carried WP marking rockets while the other pod carried flechette rockets. After being fired, the case of these rockets opened deploying hundreds of small dart-like flechettes. This could be a devastating antipersonnel weapon. This load reduced the OV-10’s target marking capability but increased its attack capability. This recognized the reduction of fighter availability due to the drawdown in Vietnam. Thus the Rustic mission shifted slightly toward attack and away from control of other fighters.

On the downside, this almost doubled the rocket load and the extra weight and drag made takeoff performance even more critical than it was at Bien Hoa. The takeoff performance was now literally “beyond the performance charts” in the OV-10 flight manual. The critical single engine failure speed (minimum control speed) was now above takeoff speed. This meant that an engine failure immediately after takeoff would result in an uncontrollable roll into the dead engine. To cope with this, the Rustic pilots held the plane on the ground until they achieved critical engine failure speed so that they could either fly the plane or eject from it if an engine quit. At Ubon, the OV-10s needed most of the runway to get airborne, which impressed even the F-4 fighter pilots. There was no margin for error. The slightest engine problem on takeoff meant that the pilot had to immediately jettision all rocket pods and the fuel tank and retract the gear if the plane had achieved flying speed—or eject if it hadn’t. There was no time to think about it. On each takeoff of that type, the plane reached a point where it cannot stop in the runway remaining, but it is not yet going fast enough to fly. Until the plane reached flying speed, the pilot is essentially just a passenger. If anything happens, he has no choice but to eject.

Rear view of an OV-10 at Ubon showing the weapons load used there. The machine guns are in the “sponsons” that support the rocket pods. Ron Van Kirk collection.

Since the Rustics were not located on the same base with their parent TASS, they had their own maintenance section headed by Don Corrie. The maintenance was superb. In January 1972, for example, 205 sorties were scheduled, but 215 were actually flown. That’s almost seven sorties a day. There was only one mission abort and one late takeoff due to maintenance. Don Corrie continued building his reputation as the best “scrounge” in the Air Force. When he needed a UHF radio, for example, and was not getting any satisfaction from the base supply system, he had a last ditch scheme that worked several times.

Ubon was home to several AC-130 Spectre gunships, which each carried two UHF radios. Don would put on an AC-130 Spectre maintenance hat, drive up to an AC-130, and swap out his inoperable radio for a good one. He always meticulously entered this fact in the aircraft logbook so the AC-130 folks wouldn’t be completely surprised. “What the hell,” he reasoned, “they can fly with only one working UHF radio and their maintenance officer can probably shake a new one loose from the supply system easier than I can.”

In January 1972, Lt. Col. Ray Stratton took over as Rustic Commander from Les Gibson. One of his first acts was to order Don Corrie to stop stealing radios from the Spectres. He watered that down considerably by flying Don back to Bien Hoa on two occasions for the specific purpose of scrounging needed aircraft parts from the Vietnamese Air Force. In a combat situation, one of the marks of a good commander is to know when the rules aren’t working and not let that affect the unit’s combat capability. It didn’t.

Unlike the maintenance troops at Bien Hoa who belonged to the Nineteenth TASS, the Ubon maintainers were Rustics and identified with that organization. They invented a gag they would spring on new OV-10 pilots. It took advantage of the fact that new pilots had never flown with an external fuel tank and knew little about it. When empty, the tank was quite light and easy to remove. After the new pilot had landed from a mission and parked, it took over a minute for the propellers to stop spinning so he could get out of the airplane. In that one-minute period, the maintenance troops would remove the fuel tank and hide it somewhere. When the pilot finally got out, one of the maintenance people would ask, “Captain, what happened to your centerline fuel tank?” The pilot, of course, didn’t know and couldn’t explain it. He had visions of being hauled up before his new commander to explain the loss of a valuable fuel tank. The maintenance guys would finally tell him what happened and that would keep them amused until the next new pilot showed up.

Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand. U.S. Air Force collection.

Living conditions at Ubon were better than they were at Bien Hoa. Even though Bien Hoa was a fully equipped air base, it was in a combat zone with actual fighting in the vicinity and the occasional rocket attack. Since Thailand wasn’t directly involved in the conflict, life was relatively peaceful. Americans shopped and dined in the nearby villages and occasionally spent a night or two in Bangkok, which had excellent military recreation and shopping facilities. Pilots were authorized three days a month in Bangkok, which included golf, sightseeing, and whatever. Because of the distance, the trip to Bangkok required a night on the train each way, but it was worth it just to get a short vacation from combat. Compared to Saigon, it was almost a resort. Because Thailand was not a combat area, it was possible for an American dependent, usually a wife, to travel to Bangkok to join her husband. There were a number of military personnel assigned to three-year tours in Thailand and the American dependent population was quite large.

By October 1971, the Rustics were well established at Ubon. The move was made with no interruption in the support of the Cambodians and Chenla II continued into December with very heavy fighting.