Although Chenla II had officially ended, nobody told the NVA. The fighting was still going on and the Rustics were still maintaining round-the-clock coverage over Cambodia. January was supposed to be in the middle of the dry season, but “wet” and “dry” were relative terms. The weather in Cambodia was highly unpredictable and there was no such thing as a daily weather briefing or forecast for Cambodia. The Rustics learned the weather by launching a plane on a mission and having the pilot radio the weather news back to Ubon. The OV-10 was fully instrumented and the Rustics were all qualified instrument pilots, so the weather was more of a nuisance than a serious problem. The worst part of it was trying to stay beneath the clouds and above the ground fire. An airplane silhouetted against cloud cover was an easier target for the enemy.

In January 1972, Ron Van Kirk, Rustic 08, was flying solo on his way south to Kompong Cham when the clouds closed down and he was in them whether he liked it or not. He climbed to 10,000 feet, which didn’t help. He couldn’t pick up a navigation signal from either Phnom Penh or Saigon and there was nobody on the ground who could help. They didn’t know where he was either.

He turned north to head back to Ubon as there was nothing he could accomplish by flying around in the soup. After about fifteen minutes, he managed to fly into a thunderstorm and things got really nasty. There was severe turbulence, constant lightning, and torrential rain. Maintaining a precise altitude or heading was impossible. Just keeping the plane right side up and out of a stall took all his efforts. That lasted for over an hour. Eventually, he flew out of the storm and could climb into blue sky, but he still couldn’t talk to anyone or pick up any navigation aid. He had been flying for nearly four hours and had no idea where he was.

His only option was to descend and pickup a landmark. He made a slow descent back into the clouds and finally broke out at about 1,000 feet over water. Nothing but water as far as he could see. It looked like he was over the ocean, but which ocean? He decided that continuing to fly north was still his best hope. If he couldn’t find himself fairly quickly, fuel would become a problem.

He finally reached land, but it was flooded and he couldn’t identify anything. He kept flying and eventually recognized the temples at Angkor north of Siem Reap. He had descended over the Tonle Sap (great lake), which was big enough to confuse anyone. It was still a forty-five-minute flight from Angkor to Ubon, and Ron spent it watching the fuel gage and thinking about what a really bad day it had been so far.

In February, Ron was flying another mission with Roger Hamann (Rustic Yankee) as his backseater. The weather was deteriorating, but wasn’t bad yet. Ron headed for Kompong Thom and checked in with Shad Kimbell (Rustic 10), whom he was replacing. Shad had been working with Sam (Hotel 21 had retreated back to Kompong Thom after the fall of Kompong Thma) and already had a target approved and Hawk 05 flight (A-37s) on the way for Ron to use. With Ron in sight, Shad marked the targets for him and headed home as he was low on fuel. On his way out, he advised that they had confirmed 12.7mm AA guns in the area. Ron contacted Sam and got a quick update on friendly troop movements as Hawk 05 checked in.

Ron went through the standard briefing litany: known enemy location, tree covered area, tops to 90 feet, weather 4,500 feet scattered, visibility 10 miles in haze, strong winds on the surface estimated 20–25 knots from the south, friendlies one klick southwest of the target in a pagoda, expect ground fire from 12.7mm AA, bail-out area is the town of Kompong Thom, alternate recovery Phnom Penh heading 185 degrees, 70 nautical miles, random run-in headings approved, FAC holding at 4,000 feet, plan two passes each.

“Roger. Hawk 05 copies. We’re descending through 7,000 feet, give us some smoke.” Ron gave them a two-second burst of smoke from his smoke tank.

“FAC’s in sight. Ready for your mark.” Ron rolled in to mark the target with a WP rocket.

“Hawk lead’s in from the northwest, I have your mark.”

“I have you in sight, lead, cleared hot.”

“Good bomb, lead. Two, drop about 15 meters short of Lead’s bomb.”

“Roger. Two’s in.”

“Cleared hot.”

“Nice secondary explosion! Lead, go about 5 meters beyond two’s bomb.”

“Lead’s in.”

“Cleared hot.”

“Another nice secondary explosion. We’ve got something here.”

“Rustic 08, this is Sam. The ground commander is reporting that the fighters are taking heavy ground fire from just north of the target area.”

“Roger that, Sam, I see it too.”

“Rustic, Hawk lead. I saw tracers from that area on my last pass, too.”

(A-37s had FM radios and could monitor the ground conversation.)

“OK guys, lets move the next run about 25 meters north and get the guns. Rustic’s in to mark. Hit my smoke.”

“Two’s in from the west.”

“In sight. Cleared hot. Shack! Real nice! Lead, put your bomb 10 meters short of that last one, and Two, you go ten meters long.” (Two more perfect hits by the Hawks resulted in a large secondary explosion).

“Rustic 08, this is Sam. The ground commander reports that the bombs have blown many guns into the air.”

“Roger that, Sam.”

“Rustic, this is Hawk lead. You were taking ground fire just south of your smoke.”

“Roger, Hawk, let’s try the mini-guns on that position. Do you need another mark?”

“Negative, Lead’s in.”

“Cleared hot.”

“Two’s in.”

“Cleared hot.”

“That’s pretty heavy fire, Rustic, looks like it might be a 12.7 quad.”

“Roger, let’s knock it off. We can’t deal with that with just our mini-guns. We’ll get it next time with bombs.”

Ron thanked the Hawks for a superb job and gave them their BDA; three large secondary explosions and one gun emplacement destroyed. Ron cleared them to RTB.

Ron checked in again with Sam. Hotel 303 (Colonel Oum) had just landed after returning from Phnom Penh. He came on the radio.

“I just got off the plane and wanted to let you know that we have no firm date yet for our trip to Ubon. Things need to get a bit quieter before we can come. It looks like the last week of February is out, maybe sometime in March.”

“No problem. We will be ready whenever you can make it.” Oum had a standing invitation to visit the Rustics at Ubon as he had at Bien Hoa and to bring Sam with him.

Ron arranged for a gunship to provide overnight protection at Kompong Thom and headed back to Ubon. For the Rustics, it had been just another normal day at the office.

About this time, President Nixon made his historic visit to China. Some sort of peace negotiations were in the works. The results of the drawdown of U.S. Forces in South Vietnam were becoming obvious. The remaining fighters and FACs could barely keep up with the workload. The Rustics were still the largest single group of experienced FACs in South East Asia and some of them were sent temporarily to NKP to help the Nail FACs with their missions in the Steel Tiger area of southern Laos.1

When the Rustics were still at Bien Hoa, the Sundog and Tilly FACs had been assigned to the Nineteenth TASS Task Force. They flew O-2s and in March 1972 they were still actively flying Rustic-type missions from Tan Son Nhut and Binh Thuy. Normally, they would cover the southern portion of Cambodia, but occasionally they would get as far north as Phnom Penh.

Doug Aitken, Rustic 16, was in the vicinity of Kompong Thom with Joe Garand, Rustic Echo, in the backseat. Doug was working with Hawk A-37s when he got a call on VHF from Sundog Alpha (the radio relay station on Nui Ba Den) asking if he could bring his fighters down to Phnom Penh. Sundog Alpha had heard a Mayday call on the radio. He suspected it was from Sundog 12, who was operating southwest of Phnom Penh. Doug broke off his activity at KPT and gave the Hawks a new rendezvous point near Phnom Penh. Because of their speed, they arrived well ahead of Doug. They had no VHF radios, but they did have FM and they attempted to contact Sundog 12 on all tactical frequencies.

Sundog Alpha had initiated the search and rescue (SAR) system and Doug was designated as the “on-scene commander.” In addition, he had Ray Stratton, Rustic 03, who had just entered Cambodia from Ubon and was following Doug to Phnom Penh. Hawk lead reported that they had contact with someone on UHF 243.0, the emergency frequency preset into all survival radios. There was a pretty good chance that Sundog 12 was down, but alive.

Since the location was not known, Doug and Ray set up a weaving search pattern starting at the last known target coordinates. The survivor, who was apparently the interpreter; not the pilot, told the Hawk fighters that he was staying close to his parachute so he could be identified, but he could not see any landmarks that would help the Rustics locate him.

About fifteen minutes later, the survivor reported that he could hear engines. Doug and Ray alternatively “jazzed” their engines which gave the OV-10 a distinctive buzzing sound. The survivor reported that he couldn’t hear either of them. Finally, Doug and Ray got close enough to hear the survivor on UHF. That helped, because the OV-10s carried UHF direction-finding equipment for just this purpose. Unfortunately, Ray Stratton’s wasn’t working and Doug wasn’t yet close enough to get a good fix. Doug was using his UHF to provide a carrier tone for rescue helicopters to home in on him.

Doug was getting short of fuel and he was really pushing it. He could never make it back to Ubon, but he knew he could get fuel at Phnom Penh in an emergency. Doug was in a left bank when a U.S. Army rescue helicopter flew directly beneath him. The survivor yelled, “I see the helicopter. It’s right over me!” Doug switched to FM, contacted the helicopter, and told him to go into orbit. He was very close to the survivor. Doug turned over command of the SAR to Ray and headed for Phnom Penh. The helicopter located the survivor and picked up the interpreter, S. Sgt. William Silva.

Sergeant Silva reported that his pilot, Lt. William Christie, Sundog 12, had been in orbit over the target when the enemy opened up with heavy AA fire. Lieutenant Christie was killed immediately. Sergeant Silva, who had only been in Vietnam a short time, grabbed the controls as he made the Mayday call heard by Sundog Alpha. When the front engine caught fire, he bailed out.

Doug made it to Phnom Penh and got his fuel. He remarked later that he didn’t really need to look at the fuel gauge. All he had to do was ask his backseater what it said. In his rearview mirror he could see his backseater leaning far to the right with his eyes transfixed on the fuel gauge on the pilot’s instrument panel.

The Rustics, Tillys, and Sundogs were never stationed together and didn’t know each other personally. That didn’t make any difference. When someone went down, the war came to a halt and all available aircraft headed for the scene to help in the SAR effort. If there were any Cambodian army units nearby, they came too. The knowledge that this would happen took some of the apprehension out of operating several hundred miles from friendly territory.

Colonel Oum made good on his promise to visit the Rustics at Ubon and bring Sam with him. In March, they flew by helicopter to Phnom Penh where they were picked up by two OV-10s and flown to Ubon. None of the Rustics at Ubon had ever met Sam face-to-face although they had all talked with him. Only the “old heads” who had been at Bien Hoa had ever met Oum.

Oum’s visit to Ubon was very productive. They discussed tactics, both theirs and the enemy’s, and established a Cambodian FAC training school at Ubon, similar to the one they had at Bien Hoa. Oum laid the groundwork for several Rustics to tour Cambodia in the coming months and visit the ground commanders they had been working with for so long. In late July, Ray Stratton, Jerry McClellan, Jack Thompson, and Marcel Morneau spent five days visiting major military installations in Cambodia. They met many of the ground commanders and discussed mutual capabilities and limitations in order to improve Rustic effectiveness.

Meanwhile, the war in South Vietnam was heating up. No one knew how the peace process would come out, but the North Vietnamese felt that if there was a truce, the lines would most likely be drawn at the positions that existed at that time. In their view, they should capture and hold as much of South Vietnam’s territory as they could. If a truce was declared, they could expect to keep that territory. In early April, some of the Rustics were deployed to Tan Son Nhut for two weeks to fly missions in the Mekong delta region where there was intense fighting. This was also the start of the NVA Eastertide Offensive. The NVA pulled some of their units out of Cambodia and launched a heavy three-pronged attack against the South Vietnamese towns of Quang Tri, Kontum, and An Loc. Since the NVA action in Cambodia was reduced, many of the Rustics were deployed to Da Nang to help thwart the NVA offensive.

The deployment came about very quickly. The Rustics flew their planes to Da Nang at night and joined several Nail FACs who had been sent from NKP. The next day, they were flying combat missions together. Da Nang was a large air base on the seacoast in I Corps, about 105 miles (170 kilometers) south of the DMZ separating North and South Vietnam. Quang Tri was about 80 miles (130 kilometers) north of Da Nang on Route 1 near the DMZ. Kontum was 112 miles (180 kilometers) south of Da Nang. An Loc was 62 miles (100 kilometers) north of Saigon and not within range of Da Nang FACs. The Rustics were needed at Quang Tri and Kontum. This deployment was to last for two months.

On May 1, Quang Tri was abandoned to the enemy and South Vietnam’s Third ARVN division had, for all practical purposes, ceased to exist. South Vietnam’s President, Nguyen Van Theiu, fired his senior commander in that area and replaced him with his best general, Ngo Quang Troung. When the Rustics arrived, the South Vietnamese forces had already retreated from Quang Tri and had abandoned hundreds of trucks, jeeps, and guns along the coastal highway (Route 1) south of Quang Tri. Many sorties were flown to destroy or disable the abandoned vehicles to prevent their capture. Regardless of the support from the VNAF and the U.S. Air Force, Quang Tri stayed in North Vietnamese hands.

This deployment showed the Rustics a new set of communist weapons. Because of the difficulty of transporting large weapons to Cambodia, the NVA units there were limited to small arms, mortars, and heavy machine guns, primarily the 12.7mm gun. The AA version of the 12.7mm was a deadly weapon against low flying aircraft and the Kalishnikov AK-47 assault rifle was superior to most of the weapons available to the Cambodian army.

At Quang Tri, the NVA used tanks and trucks that could bring artillery, rockets, and SA-7 Strela heat-seeking missiles. The Rustics didn’t realize the SA-7 had a guidance system until they were shot down by one.

On May 25, Lt. Jim Twaddell, Rustic 24, was giving Lt. Jack Shaw, Nail 77, an orientation flight over the area near the DMZ. They were working a TIC with a U.S. Army unit that was pinned down by several NVA tanks. They could easily see the tanks, but could not accurately determine the friendly position. Suddenly Jack, who was flying the plane, saw a missile coming up. He thought it was an unguided B-40 missile until it made some hard turns toward the aircraft. It was a Strela heat-seeker and he knew they were in trouble.

The missile hit the OV-10’s cargo compartment and started a fire just aft of the rear seat; probably in the hydraulic system. Don Brooks was shot down in a similar situation a year and a half earlier. Jack ejected just south of the DMZ and about 10 miles inland. Jim stayed with the plane and tried to make it offshore to the ocean. This was called “feet wet” and was considered the safest place to eject. The FACs wore life vests and carried a life raft in their survival kit and there were no enemy patrols in the ocean. The fire became too intense, though, and he ejected before reaching the coast. He landed among some sand dunes on the beach and was uninjured. Jack had landed in a rice paddy west of Route 1 and was likewise uninjured. Both were picked up within thirty minutes by ARVN helicopters and returned to Da Nang that evening.

The SA-7 Strela was a new weapon and no one knew much about it. Ray Stratton, the Rustic commander, reported what he knew to Seventh Air Force in Saigon and he was getting the idiot treatment from the Intell people down there. “There are no SA-7s. The NVA does not have SA-7s. Your plane was not shot down by an SA-7.”

“About that time, I was having coffee with Lt. Col. Abe Kardong, the Covey FAC commander at Da Nang. He got a call from the security police at the main gate saying somebody wanted to talk to us about something. We jumped in Abe’s jeep and drove down to the guard shack. There we found a Vietnamese civilian standing there holding two rocket tubes. They didn’t look like anything I had ever seen, so I opened one up and I’m looking straight at the heat-seeker head of an SA-7. I asked the Vietnamese military policeman what the civilian wanted for them. He said, ‘two packs of cigarettes.’ He got two cartons of cigarettes and we got two brand new SA-7 Strelas. My phone call, a few minutes later, to Seventh Air Force in Saigon gave me an immense amount of satisfaction.”

The Rustics also got into naval artillery bombardment. The FAC business actually got started back in World War II as a means of adjusting artillery fire. All FACs were trained to adjust artillery, but they seldom did it. Adjusting the bombardment from naval guns on ships off the coast was a little different, at least the lingo was different, and the Rustics usually carried a U.S. Marine warrant officer with them to handle the details. Chief Warrant Officer Wood was an expert on this and was flying with Ray Stratton, Rustic 03, one day.

“We had six tanks spotted, but we couldn’t get any air support. Mr. Wood calmly came on interphone from the backseat and said, ‘We’ll handle that.’ He contacted one of the Navy ships off shore—I don’t know which one, it might have been the New Jersey—and directed the fire of their big guns. They destroyed all of the tanks in short order.”

The NVA had brought a lot of Russian tanks across the DMZ and the Rustics got very proficient at spotting them and knocking them out with air strikes. They got so good that Seventh Air Force was beginning to question their BDA numbers and implied that Lieutenant Colonel Stratton was fudging the figures.

“On one occasion, General Slay [Gen. Alton Slay, Commander, Seventh Air Force] called me at Da Nang and demanded proof of our claimed tank kills. I asked for USAF recce [reconnaissance] photographs, but there weren’t any. I was wondering what I was going to do when our favorite marine, Chief Warrant Officer Wood wandered into my office and asked what the problem was. I explained it to him and told him that without photographs, we couldn’t prove that the Rustics and the Nails had killed the tanks we knew we had.”

“Not a problem,” Wood said, “I’ll take care of it.” He called out to the navy aircraft carrier operating off the coast and talked to the operations officer. The next day, the Navy flew a plane to Da Nang and delivered eight days worth of beautiful black-and-white pictures of destroyed tanks taken by their Vigilante reconnaissance squadron. The Rustics and Nails had claimed twenty-eight tanks destroyed, but there were actually thirty-two!

Ray Stratton called General Slay, who was slightly stunned by this news. He knew there were no USAF photographs, but it never occurred to him that the Navy was also flying recce missions and keeping close track of the battles. Les Gibson, Rustic 01, and Chief Warrant Officer Wood flew an OV-10 to Tan Son Nhut to personally deliver the photographs to General Slay and brief him on the missions. From then on, General Slay couldn’t say enough good things about the Rustics. At the time, there was an ongoing attempt by the Commander of the Fifty-sixth Special Operations Wing at Nakhon Phanom (the host wing for the Twenty-third TASS) to break up the Rustics and distribute their assets to other FAC units. The Rustic’s record of tank kills at Da Nang and General Slay’s support put an end to that debate.

After the deployment, Ray Stratton went to Tan Son Nhut to brief General Slay and described the Rustics as being the general’s “Swing FAC Squadron.”

“I meant that the Rustics were fully qualified to work in Vietnam, Laos, or Cambodia and current on all three sets of Rules of Engagement. General Slay nodded his head and I heard later that he used the same expression when briefing COMUSMACV.”

Down in the Kontum area, the NVA were using the same tactics they had used at Quang Tri. By May 4, Kontum was surrounded and virtually defenseless. The ARVN leadership at Kontum was no better than it had been at Quang Tri. President Thieu fired his senior commander in that area and replaced him with another excellent general, Nguyen Van Toan. The Rustics were flying many night missions and because of the distances involved, Ray Stratton set up a system where two pilots would fly an evening mission and recover to Pleiku, an air base about 22 miles (35 kilometers) south of Kontum to refuel and rearm. There, they would switch seats and fly a night mission, landing back at Da Nang in the early hours of the morning. These “Pleiku turns” as they were called, gave the FACs more hours over the target area with the same number of airplanes and pilots.

The OV-10 was not a good plane for night combat because of the way the canopy would pick up and magnify reflections of the plane’s own instrument lights. Kontum was in the Vietnamese highlands and marking targets on a dark night was very difficult. The pilots would watch each other and the instruments for any signs of disorientation or vertigo. The target marking technique involved flares and log markers and was similar to the one used by the Rustic O-2s. The O-2s were better at it, though, because they could see better. In the OV-10, it was always a struggle to give the fighters a mark they could see before the flare burned out.

Jon Safley, Rustic 19, was flying one of these Pleiku turns with “H.” Ownby, a Nail FAC in the backseat. The night was pitch black and they were working a TIC with an ARVN commander who didn’t speak English. He was relaying his instructions through a U.S.Army advisor in Pleiku. That was always a high risk situation and the chances for error were multiplied. Jon completed the air strike, sent the fighters home, and called the Army advisor for BDA.

“I can’t raise the ARVN commander. I think you may have had a short round.” That was the one thing that no FAC wanted to hear. “Short round” was the code for munitions dropped on friendly troops.2 All FACs have had the experience of watching a bomb or a can of napalm go slightly astray and had the terrible feeling that they might just have killed or wounded some of the people they were trying to protect. There is no feeling quite like it.

After about ten minutes, the Army advisor came back on the radio. “All is well. The bombs were close and frightened the ARVN troops. They dropped their radio as they ran and just now found it. No injuries.”

Jon and “H.” headed for Da Nang. They’d had enough excitement for one night.

President Nixon’s reaction to the full-scale invasion from North Vietnam was to increase American airpower without increasing American ground forces. The increase included 119 more B-52s, four more Navy aircraft carriers and four Marine fighter squadrons. Nixon also launched Operation Linebacker, which included air strikes in North Vietnam and the mining of Haiphong Harbor.3

In the end, the ARVN counteroffensive headed by General Truong retook Quang Tri city and routed the six opposing NVA divisions. He did it with massive U.S. firepower including B-52s and offshore naval bombardment. In the Kontum area, General Toan had essentially the same success.

In the meantime, the fighting was still going on in Cambodia. The Rustics, even with the Tillys and the Sundogs helping, were spread very thin and the air support suffered. In May 1972, the American Embassy Air Attaché in Phnom Penh (Lt. Col. Mark Berent) complained about the lack of air support for the Cambodian army. With the ARVN counteroffensive going fairly well in Vietnam, the Rustics were sent back to Ubon and the war in Cambodia.

The problem in Cambodia was that there were few fighters available and the OV-10 could not carry a really effective load of weapons. In theory, it could carry five Mk-82 500 pound bombs, but that was without the external fuel tank and any marking rockets. At that weight, the OV-10 takeoff roll on a hot day at Ubon would attract spectators and bets might be placed.

There were Cambodian T-28s available, but Lt. Col. Kohn Oum was not there to lead them. He was still in the United States in advanced training courses, and most of the other Cambodian pilots did not speak English and lacked his experience.

After returning to Ubon, Jon Safley was working a target just east of Angkor. The rules of engagement were absolutely clear on the temples at Angkor: Do not put any munitions anywhere near them. Jon VR’d around the area and found piles of enemy supplies and some enemy spider holes (similar to the foxholes of WW II) plainly visible about 110 yards (100 meters) east of a wall around one of the smaller temples. He reported this to Blue Chip and went back to VR’ing. He didn’t really expect an answer.

He was surprised when Blue Chip sent him a pair of Cambodian T-28s carrying Mk-82 slicks. That in itself was a slight violation of the rules of engagement. Rustic FACs weren’t supposed to control Cambodian fighters (although they regularly did) and the FACs were definitely not to participate in anything that might result in damage to any pagoda, temple, monument, historical structure, or anything that looked like one. Someone was on duty at Blue Chip that day who clearly understood the situation and applied the best available solution to it.

Since the NVA spider holes paralleled the wall, it should be reasonably safe to run the fighters parallel to the wall. Bomb aiming errors were almost always in range, not azimuth. Jon briefed the fighters carefully and demonstrated the run-in heading he wanted as he marked the target.

“Got it?”

“Roger. Got it.” The fighters then proceeded to run directly at the wall which was perpendicular to the briefed run-in line.

“Knock it off! Go through dry!” The fighters understood that and pulled off without dropping anything.

“OK. We’ll be a three-ship flight and I’ll be the leader. You follow me. OK?”

“OK.”

Jon got the fighters in line to follow him. He rolled in and marked the target and pulled up into a standard fighter pattern to get ready for the next pass. Jon made four passes, firing a smoke rocket on each one, and the Cambodian fighter pilots hit his smoke every time. They had excellent BDA and the ground commander was very happy. The NVA was out of business in that area. There was nothing wrong with the skills of the Cambodian pilots. It was just their English that needed work.

In spite of all the training, no one really knows how they will react to a combat situation until they get involved in one. Ron Van Kirk was working a pair of F-4s from Ubon on a target just south of the Thai border. All three aircraft had been taking ground fire on every pass. The lead fighter had just pulled off and Ron was ready to clear the wingman in, but he couldn’t find him and he didn’t answer any radio calls. Ron and the lead fighter tried all frequencies, listened for an emergency signal on “guard” channel, and looked for any evidence of smoke that would indicate a crash. Lead climbed to a higher altitude and contacted Ubon Approach Control. The missing F-4 had just called in for landing instructions. Ron had two more hours to fly on his mission and spent much of it wondering what had happened to the F-4 wingman.

It was close to 8 P.M. when Ron landed, finished debriefing, and headed for the Officers Club for dinner.

I found the intrepid aviator in the bar of the club and he was working on a good drunk. On the stool next to him was his flight helmet. You could clearly see where a 12.7mm round had gone in the front of his helmet and out the top. If you looked closely, you could see a matching mark where it had grazed his forehead on the way through. He had missed death by a mere fraction of an inch. When that happened, he just lit the afterburners and headed for home. He could remember nothing from the time he took the hit until he contacted Ubon for landing. This didn’t seem like the right time to mention that a simple “good-bye” would have been appropriate, so I bought him another drink and headed for the dining room for dinner. It tasted unusually good.

August 1972 saw another Rustic milestone. The Rustic backseaters were being gradually replaced by newly arriving French-speaking OV-10 pilots. The final flights of the enlisted backseaters occurred on August 25. Roger Hamman (Rustic Yankee) flew with Jerry McClellan (Rustic 14) and Nick Lewis (Rustic Bravo) flew with Bob Andrews (Rustic 07.) Although they flew different missions, they returned to Ubon at the same time. Jerry and Bob joined in formation for the landing and taxied to the parking ramp together. Nick and Roger were expecting the traditional champagne shower that came with the final combat flight. Roger got his, but Nick was doused with milk in deference to his Mormon religion. Thus ended a unique part of USAF history. For more than two years, nearly fifty enlisted men flew combat missions in a high performance tactical aircraft and became part of a unique combat team. They shared three characteristics. They were all volunteers; they were all dedicated to the mission; and, of course, they all spoke French. Without them, the Rustic story would have been a very short one.

In September 1972, Colonel Oum’s disagreements with the military headquarters staff in Phnom Penh were beginning to catch up with him. The headquarters wanted to send his entire brigade to South Vietnam for training on the AR-15 assault rifle now being supplied by the Americans. Oum felt this was a waste of time and money. With ten or fifteen qualified AR-15 instructors, he could train his own brigade in just a few days right where they were. The entire brigade was sent to South Vietnam for training and when they returned, Colonel Oum was no longer their commander. He was reassigned as chief of staff of an army group at Siem Reap.

At Siem Reap, Oum found even more problems, particularly corruption, which was becoming widespread in the Cambodian army. Supplies meant for the army units continued to show up on the black market and in enemy hands. Nonexistent soldiers were filling the ranks while the real soldiers went unpaid and unfed. Greedy officers were buying Mercedes for themselves and jewelry for their wives.4

Oum refused to go along with any of this, so he was put in charge of a group of sixty officers sent to Political Warfare College in Taiwan.

Meanwhile, Phnom Penh was facing an acute shortage of rice in spite of all efforts to supply it by ship convoy. For the first time, transport aircraft were used to deliver rice to Phnom Penh. The city itself had been largely immune to the fighting, but was beginning to feel the impact of it.

In October, the Rustics were sent back to Tan Son Nhut to help the South Vietnamese army capture and hold portions of the southern delta region. The peace negotiations in Paris had changed from a cease-fire and withdrawal to prewar positions to a cease-fire in place.5 The war was turning into a real estate grab. The Rustics worked with whatever fighters were available including Air Force, Navy, Marine Corps and VNAF. The A-7 “Sluf” (short little ugly fellow) had been in Vietnam since 1970 and used occasionally by the Rustics. Now, they were arriving in quantities to replace the A-1s as helicopter escorts on SAR missions and proved to be an excellent close air support fighter. It had good “play” time, carried a lot of munitions, and could deliver them very accurately. It also had a complete set of radios including FM.

While the Rustics were deployed to Tan Son Nhut, Lt. Col. Bill Ernst replaced Ray Stratton as Rustic commander. The Rustics flew 450 sorties from Tan Son Nhut before returning to Ubon in mid-December.

Back at Ubon, the Rustics began flying regular missions over the trail in the Steel Tiger area of Laos. That was a long flight from Ubon, but there was a lot of action. While they were still miles away, the Rustic pilots could see dust trails kicked up by the “movers” (North Vietnamese trucks carrying supplies down the Ho Chi Minh trail). The Rustics would use any available fighters or gunships. By now, the new C-130E Spectre gunships were equipped with both 20mm and 40mm guns and a 105mm howitzer. Watching one of those at work was an awesome sight.

Communications were a problem particularly if there were friendly Laotian army units in the area. In one case, Bill Ernst (Rustic 04) used an Air America plane that was carrying a Laotian passenger. The commander on the ground spoke to the passenger in Lao, who translated it in French to the Air America pilot, who relayed it to Bill Ernst in English, who could switch radios and instruct the fighters.

In late December, the Paris peace negotiations broke down and President Nixon sent B-52s to bomb Hanoi in an operation called Linebacker II. That restarted the peace negotiations and in early January, a treaty was signed calling for a cease-fire in Vietnam on January 29, 1973. The cease-fire in Laos would begin on February 23, 1973. There would be no cease-fire in Cambodia as Cambodia was not represented in Paris and was not part of the peace negotiation process.

On January 24, 1973, President Nixon announced the cease-fire in a speech to the American public. This led to an interesting situation halfway around the world in Cambodia.

Nixon’s speech was picked up by Radio Australia and rebroadcast on their HF frequency. At the time, Rick Scaling (Rustic 09) was working with Sam (Hotel 21) and putting in an air strike near Prey Totung. He was talking to Sam on FM, and the fighters on UHF, which was all recorded on an ABCCC aircraft orbiting overhead. The ABCCC crew was also listening to Radio Australia on HF and portions of Nixon’s speech were recorded in the background. Because the three radio frequencies were in use at the same time, portions of the tape were unintelligible. The intelligible parts contrast President Nixon’s words with the words of an actual combat air strike in progress.6

After the cease-fire in Vietnam on January 29, the Rustic activity in Laos picked up. The North Vietnamese were still rushing supplies down the Ho Chi Minh trail to their units in South Vietnam. Fighters that could no longer be used in Vietnam found plenty of work in Laos until the cease-fire there on February 23. Shortly before the Laotian cease-fire, the repatriation of American prisoners began.

After the cease-fire in Laos, Cambodia suddenly became the only active battle ground in all of Southeast Asia. This had two results. First, communist forces began infiltrating Cambodia in greater numbers. The Khmer Rouge (Cambodian communists) had grown to become an effective force and enemy operations against the forces of the Khmer Republic increased significantly. Second, all air assets that had been used in Laos and Vietnam suddenly became available to the Rustics in Cambodia. Blue Chip was still running things from Seventh Air Force in Saigon, but was in the process of moving to Nakhon Phanom in Thailand. They were increasing the number of fighter and gunship sorties and taxing the ability of the Rustics to handle them.

The Rustic’s parent unit, the Twenty-third TASS at Nakhon Phanom began rotating their Nail FACs to Ubon to help the Rustics. This created a minor problem as most of the Nails’ work had been over the Ho Chi Minh trail in Laos. They had seldom worked directly with friendly ground commanders and troops-in-contact (TIC) situations. Also, the Nails were not familiar with the Cambodian geography or tactical situation and few of them spoke French. The Nails were outstanding FACs, though, and fast learners. They mastered their new mission quickly.

Because of the additional air assets, the Cambodian army was able to keep Route 4 open from Phnom Penh to Kompong Som, which improved Phnom Penh’s supply situation and provided plenty of business for the Rustics and Nails.

March 1973 saw another improvement in Rustic operations. Lt. Col. Mark Berent, the air attaché at the American embassy in Phnom Penh, arranged for the Rustics to routinely land at Phnom Penh to refuel. There was no longer any secrecy about the air operation in Cambodia and no reason not to land at Phnom Penh. These were called “Phnom Penh Turns” and significantly increased the Rustics’ on-station time. The flying time from Ubon to the Phnom Penh area was about an hour and fifteen minutes each way and refueling at Phnom Penh saved about two and a half hours of nonproductive travel. Sustained support of operations along Route 4 to Kompong Som would have been almost impossible without refueling at Phnom Penh.

The airport at Phnom Penh was something of a problem. It was poorly maintained and the runway was full of potholes and debris. The embassy laid down strict rules on how many U.S. personnel could be on the ground there at any one time and it was not uncommon for one Rustic to be orbiting the airport waiting for another Rustic to get airborne and make room for him.

At Phnom Penh, the Cambodian Air Force took care of refueling the OV-10 while the pilot found some shade and ate a Cambodian box lunch. The contents of the lunch box were never accurately determined. They were referred to as “monkey balls and rice” and eaten anyway.

In April 1973, the Rustics suffered a major loss when Rustic 07, 1st Lt. Joe Gambino was shot down near Kompong Thom. He was flying solo and working with the ground commander in that area, Brig. Gen. Teap Ben. According to witnesses, Joe’s OV-10 was hit by automatic weapons, probably 12.7mm machine guns, and caught fire. He ejected at low altitude and his parachute opened, but he did not survive the landing. A Cambodian platoon recovered his body, which was draped in a Cambodian flag and returned to Ubon that same day. A service honoring Joe was held the next day at the Ubon chapel and his body was loaded onto a C-130 for the first leg of his trip home to New York City.

The Cambodians took the loss hard and their sorrow could be heard in the voices of their radio operators; particularly Sam’s. Soon after Joe’s death, Lt. Col. Bill Ernst, the Rustic commander, received a letter from Brig. Gen. Teap Ben.

Monsieur the Lieutenant Colonel:

On the occasion of the cruel loss of Lieutenant Joe Gambino, who died tragically the Seventh of April, 1973, on the field of honor of Kompong Thom: in the name of the officers, noncommissioned officers, soldiers, civil servants, civilian population, and in my own name, permit me to express to you as well as to the family of the regrettably lost, who has valiantly fought on our side for the cause of the Khmer Republic, my saddest condolences. The Khmer Republic, and in particular the Province of Kompong Thom, has lost in the person of Lieutenant Joe Gambino, a sincere friend and brave companion-in-arms. Be assured, Monsieur the Lieutenant Colonel, the assurances of my highest consideration. (Signed) Brigadier General Teap Ben.

During this time period, Lt. Col. Kohn Oum returned from the United States and became the commander of the Cambodian T-28 “Scorpions” and the Chief of Base Operations at Phnom Penh’s Pochentong Airport.

In May, Lt. Col. Bill Powers replaced Bill Ernst as the Rustic Commander. Bill Powers left within a month and Maj. Si Dahle took his place. Major Dahle was the last Rustic Commander.

Ned Helm, Rustic 15, managed to make the news in early July 1973. He was working with a set of A-7s just east of Phnom Penh when the lead A-7 suddenly broke off the attack and started heading west, apparently NORDO (no radio) as he wasn’t answering any of his wingman’s calls. The A-7s had FM radios and Ned was able to contact him on the tactical FM frequency. He had lost all oil pressure and had decided to spend the night in Phnom Penh instead of under a tree with his parachute.

Ned called Pochentong tower and told them an A-7 was inbound for an immediate emergency landing. Ned also headed for Phnom Penh and told the A-7 wingman to terminate the attack and follow him. He then called Scorpion Ops to advise the air attaché (Mark Berent) that he was about to have a visitor. Mark was spending enough time at Pochentong Airport to deserve his own office.

The A-7 landed safely and taxied to a revetment. With everything under control, Ned and the A-7 wingman went back to work on the target.

When Ned was done with his first mission, he landed at Phnom Penh for fuel and lunch. After parking, he noted that the parked A-7 wasn’t showing any obvious signs of an oil leak. The problem was probably failure of the oil pressure transmitter or the pressure gage itself. With a jet engine, though, total loss of oil was usually followed by severe engine failure within a minute or two. The pilots flying single engine jets tended to take the oil pressure indicator seriously.

Ned wandered into flight operations to pick up his lunch and talk to the Scorpion Ops Officer, Major Kahn, who told him to call Blue Chip in Saigon. Blue Chip canceled the second half of his double mission and told him to fly the A-7 pilot back to his base at Korat.

Eventually, Mark Berent and Mike Lang, the A-7 pilot, came in and Ned explained the change in plans. He and Mike went out to the OV-10 for the requisite lecture on the plane’s ejection seat, canopy, radios, and so on. Ned hooked up Mike’s harness for him and got the Koch fittings attached from the seat.7 Mike was a very large person, and both were skeptical about whether he could safely eject or not. Ned also gave him specific instructions on closing the right canopy hatch and making sure it was locked. If not locked, it would come off in flight and scare everyone.

Ned fired up the engines and headed for the runway for takeoff. At about 600 feet above the ground, he heard a loud “bang” and the plane rolled viciously to the left. He pulled both throttles to idle and noted that the left engine had failed and the propeller auto-feathered. The right engine was not running well, but it was still putting out power. Ned turned left (which the plane wanted to do anyway), back to the airport, and punched the jettison button to get rid of the belly tank and rocket pods. Nothing happened. He pulled the manual jettison handle and that also did nothing. He was stuck with a plane that absolutely would not maintain altitude with an engine shut down and no way to get rid of all the weight and drag hanging beneath it. Ejection was beginning to look like a real possibility. He looked in his rearview mirror and he could see what had happened. Mike’s right canopy hatch was gone and the left engine had probably eaten it.

Realizing that Mike might not survive an ejection, Ned told him to hang on and get a good grip on the seat handles. If things turned really hopeless, Ned could initiate the ejection for both of them from the front seat. About then the electrical system failed leaving them without radios.

They were on downwind leg to the runway, but still losing altitude. Ned bent the plane around in a tight left turn and landed right over the top of an AU-24, which had also just landed. The landing rollout was uneventful except for the heavy breathing from both seats. After parking, the Nail FAC commander, Howie Pierson, wandered up and commented that Ned really shouldn’t demonstrate single-engine approaches in a combat zone with an unqualified passenger on board. He was kidding, of course, but his sense of humor broke the tension. Ned and Mike were both ferried home in other aircraft. Mike decided that he really didn’t care much for the OV-10.

Sam (Sam Sok) and Rick Scaling at Pochentong Airport, Phnom Penh, 1973. Mark Berent collection.

Because of the condition of the Pochentong runway, the pilots were leery of both takeoff and landing. One day, shortly after Ned Helm’s emergency, Rick Scaling, Rustic 09, demonstrated why. He had finished his lunch and was back in his plane, fully fueled, and thundering down the runway on takeoff. Suddenly his left main tire hit something on the runway and blew out. Rick was not up to flying speed yet, and the plane was not going to accelerate with a blown tire. The OV-10 veered left off the runway into the grass and headed for a dirt berm along the airport access road. Rick used full brakes and full reverse on both engines, but the brakes weren’t very effective on grass, particularly with one tire blown. Rick didn’t think he could get the plane stopped and he was running out of options. Considering all the munitions and the 230 gallons of fuel in the belly tank beneath him, ejecting suddenly looked like a very good idea.

The marvelous LW-3B ejection seat and parachute worked perfectly and Rick landed unhurt. So did the OV-10. It rolled into a small rut in the ground and stopped a few feet from the berm with both engines still whining away in reverse. Rick walked over to it, reached in through the broken canopy, and shut off the engines. Mark Berent, the embassy air attaché, was at the airport and saw the whole thing. He went out and helped Rick gather up his parachute.

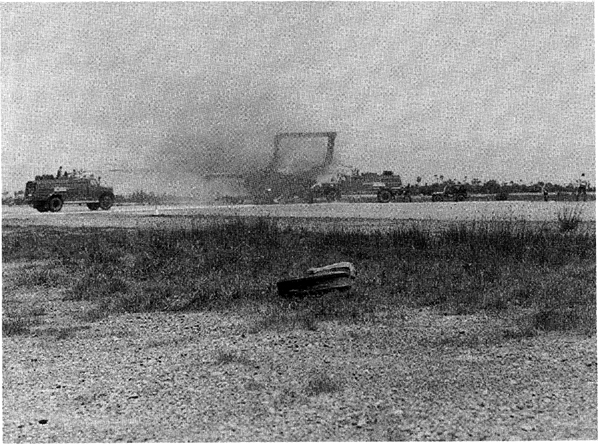

Results of Ned Helm’s landing with nose gear failure and fire at Phnom Penh. Note failed nose landing gear in the foreground. Mark Berent collection.

Rick spent the night in a Phnom Penh hotel and dined that evening with Sam (Hotel 21’s radio operator). Sam happened to be visiting his family and heard about Rick’s adventure. Four days later, the OV-10 was flying again with a new ejection seat, canopy and tire.

About then, early July, 1973, President Nixon announced the date for termination of all U.S. air activities in Southeast Asia: August 15, 1973. The days of the Rustics were numbered and the Phnom Penh Turns continued right up until the final day.

A few days after Rick Scaling’s ejection at Phnom Penh, Ned Helm was again in the news. Phnom Penh was effectively under siege and the Khmer Rouge were making a strong effort to capture both the city and the airport. There was plenty of air support available, and Ned was at 10,000 feet over Phnom Penh acting as the “High FAC.” The fighters would check in with him and he would brief them and park them in orbit until the “Low FAC” was ready for them. This system was a very efficient way to manage large numbers of fighters.

Lt. Col. Mark Berent, Air Attaché, United States Embassy, Phnom Penh, and Cambodian (Khmer) friends. Mark Berent collection.

After about an hour and a half of this, his number one (left) engine failed and auto-feathered without warning. He was having his second single-engine landing experience within a week. He had plenty of altitude and flew a “textbook” engine-out pattern to the Pochentong runway. He landed on the main gear with no problem. When he lowered the nose wheel to the runway, it collapsed and all of a sudden he was skidding down the runway on the main landing gear and the belly tank. His escort (a Nail FAC in another OV-10) told him he was on fire. Ejection was not an option, as the ejection seat wouldn’t go straight up because of the collapsed nose gear. Ned rode it out and dove out of the cockpit as soon as he could get untangled from all the straps holding him in. A Cambodian fire truck pulled up and extinguished the belly tank fuel fire. Ned managed to get away with only a sprained ankle, a sore back, and a new nickname—from then on he was known as “Crash” Helm.

One of the first on the scene was Mark Berent who had been beside the runway taking pictures of Ned’s landing. That eliminated a lot of discussion about the quality of the landing. Investigation revealed a half-inch hole going in and out of the nose gear landing strut. Ned had been potted by a 12.7mm gun while on final approach with the landing gear down. Case closed.

The volume of Rustic and Nail operations at Pochentong airport remained high and the number of aircraft needing maintenance or repair was taxing the resources of the Twenty-third TASS at NKP and their Rustic Operating Location at Ubon. Because of the attacks on the airport by the Khmer Rouge, leaving an OV-10 parked there overnight merely provided “bait” for the attackers. Nevertheless, the Rustics kept up a full schedule and lost no planes to ground attacks at the airport.