The bright lights of the Jewish hilltop suburbs shine above the darkened Palestinian villages and towns in the valleys of Samaria and Judea. (fig. 5.10.1) In its contrast of light and darkness, the Samarian night reveals more than it hides: the illuminated urban layout of the Israeli settlements and their connected road systems shows itself as a network cast onto the mountains and hilltops of the occupied territories of the West Bank. This network is one of power and surveillance, of one population’s control over another. At night, the other side of what by day might seem like a harmless suburban environment of single-family detached homes is exposed as an invasive and violent intrusion on the landscape and livelihoods of the Palestinians it seeks to suppress.

5.10.1 Night view of the Cross-Samaria Highway with the settlement Barkan on the hilltop in the background

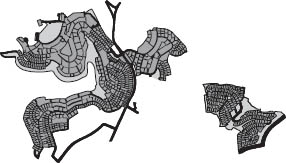

In 2003 Eyal Weizman and I published A Civilian Occupation: The Politics of Israeli Architecture, a collection of essays, photos, and plans that explore how architecture, urban planning, and landscape design have had a hand in shaping the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.1 The project viewed the landscape and built environment of the occupied territories of the West Bank through the conventional tools of urban development: infrastructure and housing. It construed the landscape as a battlefield—a spatial matrix of forces in a continuous process of transformation, adaptation, construction, and obliteration. We argued that in this environment, where architecture and planning had been systematically instrumentalized as executive arms of the Israeli state, planning decisions directly serviced national and geopolitical objectives to seize land and exercise control over the Palestinian population. Unfortunately, these arguments remain relevant today. Some of these issues, and a description of a selection of settlement plans, follow. (fig. 5.10.2)

5.10.2 Jewish Settlements in the West Bank, Built-up Areas and Land Reserves, May 2002. Section from map of Israeli settlements in the West Bank. B’Tselem, Eyal Weizman. Reprinted from Rafi Segal, Eyal Weizman, A Civilian Occupation: The Politics of Israeli Architecture.

The first Jewish settlements of the West Bank were established in the Jordan Valley during the early years of Israel’s occupation, 1967–77. Fifteen agricultural villages (kibbutzim and moshavim) were then built under the Labor government’s rule to establish a secure border with Jordan. Following the political turnabout of 1977, which saw the right-wing Likud Party rise to power, the political climate in Israel changed. Settlements began to be established in the mountain region in and around the Palestinian cities and villages, with the intention of annexing the area to prevent territorial concessions. It was during this time that a suburban model replaced the agricultural settlement as the occupation’s prevailing urban typology. These communities were designed, and often marketed, as extended suburbs of the larger Jerusalem metropolitan area. Much of the West Bank began to be considered a part of the sacred, biblical landscape associated with Jerusalem. As Weizman explains, “The extension of the city’s ‘holiness’ to the new suburbs was conceived as part of Israeli attempts to generate widespread public acceptance of the newly annexed territories.”2

The mountain peaks of the West Bank easily lend themselves to state seizure. Land ownership has been hard to ascertain ever since the Ottoman rule of Palestine, when residents paid tax only on the lands they cultivated. These lands later reverted to private ownership. Areas determined to be under continuous cultivation remained in private Palestinian ownership, and the rest was declared state property. Since Palestinian-cultivated areas are mainly located in valleys and along mountain slopes where agriculturally suitable soils exist, the barren hilltops, along with isolated plots and discontinuous islands around the mountain peaks, became easy targets for annexation by the state.3

These hilltop areas became the sites of Jewish settlements, usually as dormitory communities. Assisted by considerable government subsidies, a settler could purchase a newly built, single-family detached home for the price of a small apartment in Tel Aviv. These suburbs offered newly constructed homes and roads, along with plenty of space, clean air, and panoramic hilltop views. It was all less than half an hour away from the city centers of either Jerusalem or Tel Aviv.

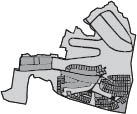

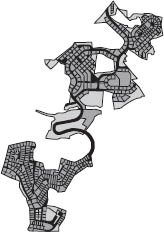

Most of these settlements are structured in a concentric layout, with the topographical contours of the mountain retraced as lines of infrastructure. The roads are laid out in rings around the summit, with water, sewage, and electricity lines buried beneath them. Land is divided into equal, repetitive lots, each containing a single-family house sited along the road, and facing the landscape. While the ideal form for these suburbs is the circle, in reality the plan is distorted, as it has had to adapt to irregular topography and the form and extents of available state land.

Vision plays a key role in every aspect of the design. The arrangement of homes around the summits directs the residents’ gaze outward. This produces sight lines for surveying the landscape to attain different forms of power: strategic, in overlooking main traffic arteries; controlling, by watching over Palestinian towns and villages; and defensive, in overlooking the immediate surroundings and approach roads. The settlements are, in effect, optical devices designed to exercise control through supervision and surveillance.

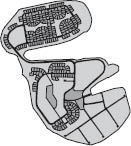

The spatial layout of these settlements—the arrangement of infrastructure and distribution of house lots—reveals the design principles and strategies at play. (fig. 5.10.3) The diagrams presented here are abstracted urban plans of West Bank Jewish settlements in which the roads are rendered in black, housing lots in dark gray, and commercial or public land uses in medium gray (these only appear in a few settlements) and the lightest gray. A contour line depicts the extent of the municipal boundaries of each settlement; included within these borders are areas that have already been designated for future expansion as part of the master plan. The light gray areas reveal where these settlements will grow in the future. The three primary urban elements that have created this typology—roads, single-family lots, and developable land—are the core elements that make up suburbia.

Tapuah

Area: Nablus

Population: 350

Established: 1978

Location on map: F6

Latitude: 650

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: M. Ravid

Giva’at-Ze’ev

Area: Ramallah

Population: 10300

Established: 1983

Location on map: E9

Latitude: 760

Type: Local Council

Planner: Nehemya Gorali

Mizpe-Yeriho

Area: Jericho

Population: 1200

Established: 1978

Location on map: G9

Latitude: 160

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: The Settlement Planning Department

Talmon

Area: Ramallah

Population: 1200

Established: 1989

Location on map: E8

Latitude: 560

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: A. Wilenberg, Gile’adi

Na’aran

Ma’on

Area: Hebron

Population: 250

Established: 1981

Location on map: E14

Latitude: 770

Type: Community Settlement

Ofarim

Qedar

Area: Jerusalem

Population: 450

Established: 1985

Location on map: G10

Latitude: 440

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: The Settlement Planning Department

Tomer

Area: Jordan Valley

Population: 300

Established: 1976

Location on map: H7

Latitude: -220

Type: Moshav

Planner: Yiga’al Levy

Oranit

Area: Jenin

Population: 5000

Established: 1985

Location on map: D6

Latitude: 140

Type: Local Council

Noqedim

Area: Bethlehem

Population: 600

Established: 1982

Location on map: F11

Latitude: 570

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: The Settlement Division of the Jewish Agency

Sal’it

Area: Tul Karem

Population: 500

Established: 1977

Location on map: D4

Latitude: 260

Type: Moshav

Kochav-Ya’acov

Area: Ramallah

Population: 2200

Established: 1984

Location on map: F8

Latitude: 765

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: Eyal Itzki

Na’ale

Area: Ramallah

Population: 150

Established: 1985

Location on map: D8

Latitude: 430

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: A. Wizenthal

Yafit

Area: Jordan Valley

Population: 150

Established: 1980

Location on map: H2

Latitude: -245

Type: Moshav

Ma’ale Levona

Area: Nablus

Population: 500

Established: 1982

Location on map: F6

Latitude: 734

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: Rachel Walden

Bet-Horon

Area: Ramallah

Population: 750

Established: 1977

Location on map: E8

Latitude: 620

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: The Settlement Planning Department

Rimmonim

Area: Jericho

Population: 500

Established: 1977

Location on map: G8

Latitude: 680

Type: Moshav

Planner: The Settlement Planning Department

Ateret

Area: Ramallah

Population: 300

Established: 1981

Location on map: E7

Latitude: 720

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: S. Melman, A. Kaplan

Zufim

Area: Tul Karem

Population: 850

Established: 1989

Location on map: D5

Latitude: 145

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: Eilon Meromi, Gertner-Gibor-Koms

Rechan

Area: Jenin

Population: 120

Established: 1977

Location on map: E2

Latitude: 375

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: A. Inbar, M. Ravid

Revava

Area: Salfit

Population: 500

Established: 1991

Location on map: E6

Latitude: 415

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: M. Ravid

Nofim

Area: Nablus

Population: 400

Established: 1980

Location on map: E5

Latitude: 380

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: Rachel Walden

Elazar

Area: Bethlehem

Population: 200

Established: 1975

Location on map: E11

Latitude: 910

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: The Settlement Planning Department

Hamra

Area: Jordan Valley

Population: 150

Established: 1971

Location on map: H15

Latitude: -55

Type: Moshav

Ro’i

Area: Jordan Valley

Population: 150

Established: 1976

Location on map: H4

Latitude: 30

Type: Moshav

Hinanit

Area: Jenin

Population: 500

Established: 1980

Location on map: E2

Latitude: 385

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: A. Inbar

Elon-Moreh

Area: Nablus

Population: 1000

Established: 1979

Location on map: G4

Latitude: 640

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: M. Ravid

Mechora

Area: Jordan Valley

Population: 150

Established: 1973

Location on map: H5

Latitude: 225

Type: Moshav

Geva Binyamin

Area: Ramallah

Population: 1000

Established: 1984

Location on map: F9

Latitude: 640

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: The Settlement Planning Department

Hermesh

Area: Jenin

Population: 300

Established: 1982

Location on map: E2

Latitude: 270

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: Shahar Yehoshua

Mehola

Area: Jordan Valley

Population: 300

Established: 1968

Location on map: H3

Latitude: -180

Type: Moshav

Geva’ot

Eli

Area: Nablus

Population: 2500

Established: 1984

Location on map: F6

Latitude: 700

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: The Settlement Planning Department

Ganim

Area: Jenin

Population: 100

Established: 1983

Location on map: G2

Latitude: 280

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: M. Ravid, A. Inbar, Ya’ad Architects

Kfar-Edumim

Area: Jerusalem

Population: 1700

Established: 1979

Location on map: G9

Latitude: 360

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: Samach-Abramowitz, Moshe Goldwasser, Gideon Harlap

Shaqed

Area: Jenin

Population: 500

Established: 1981

Location on map: E2

Latitude: 410

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: Gonen Architects

Gittit

Area: Jordan Valley

Population: 100

Established: 1972

Location on map: G6

Latitude: 305

Type: Moshav

Karmei-Zur

Area: Hebron

Population: 500

Established: 1984

Location on map: E11

Latitude: 940

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: The Settlement Division of the Jewish Agency

Nili

Area: Ramallah

Population: 700

Established: 1981

Location on map: D8

Latitude: 360

Type: Community Settlement

Planner: Bina Nudelman

Elqana

Area: Qalqilia

Population: 3000

Established: 1977

Location on map: D6

Latitude: 235

Type: Local Council

Dolev

Area: Ramallah

Population: 900

Established: 1983

Location on map: E8

Latitude: 600

Type: Community Settlement

Na’ama

Area: Jordan Valley

Population: 130

Established: 1982

Location on map: H3

Latitude: -200

Type: Moshav

5.10.3 Plans of settlements in the West Bank, reprinted from Segal and Weizman, A Civilian Occupation

When examined as a series, these plans further highlight the adaptability of this typology to diverse topographical conditions and the availability of land. The concentric layout of ring roads and culs-de-sac, where the roads tend to follow the horizontal topographical lines or the mountain ridges, allows a maximum outer exposure to the house lots; the plans act as two-dimensional imprints of the spatial form of the hilltops they occupy. From a planning perspective, their design is not efficient as an attempt to minimize the ratio between infrastructure and the number of houses, or to concentrate residential development in one area. On the contrary, the roads often far exceed what’s required. Housing lots are scattered along the edges of settlements to grab and occupy as much land as possible, and to maximize the settlers’ field of vision over the territory below.

Through their shared road system and geographic location, the settlements form a large-scale network of civilian fortifications that tactically survey territory and enact national security goals under the guise of suburban living. By placing settlers across the landscape, the Israeli government administers power not only through agencies of state power and control such as the police and military; it also “drafts” civilians to inspect, control, and subdue the Palestinian population.

On the West Bank, the suburb, that most ubiquitous of urban typologies, rears its dark side. It transforms the landscape into a terrifying weapon of suppression that permits one world to impose its power on another. As this visual and physical network continues to expand, multiple separations and boundaries are continuously imposed on the world below (the Palestinians), while strengthening the connections between the Israeli hilltop settlements above. And as individual settlements expand, their presence gradually closes in, more and more, on any possibility of future Palestinian urban growth.

The barrier wall constructed by Israel in the past decade is yet another element of control. The wall further expands what the settlements have been doing: isolating and fragmenting the fabric of Palestinian towns and villages while enhancing the physical and visual space between the disparate Jewish settlements. In this case, the wall does not act as a single binary divide between sovereign entities. Rather, it serves as a series of cuts, barriers, and roadblocks that subdivides and entraps part of the landscape and its population—the Palestinians—while it allows maximum “free” space for the other part, the Jewish settlers. In this territorial conflict the Jewish suburbs of the West Bank are presented by the state as the raison d’être for all security measures.

For what is the single-family home suburban development, if not the urban typology most emblematic of the freedom to own land, of mobility, and of the right to access space? (fig. 5.10.4)

The flight of the middle class from the cities to the “protective” walls of suburbia gains new meaning in the context of the occupation of the West Bank. In a daunting reversal, the act of retreat from the “conflicts” of the city has become an intrusive act, perpetuating a conflict on a much larger scale. The adaptability and flexibility of the suburban typology makes it an effective tool of territorial control that can be implemented in a range of scales, to comprise a few homes or an entire neighborhood, and flexible enough to conform to the specific topographical conditions of different sites.

Moreover, the social homogeneity that is characteristic of this suburban population serves the political aim of the occupation: that of acting as a single, unified front against the local hostile population. The monotonous architecture of the settlement typology, which reflects this homogeneity, turns urban sprawl in the West Bank settlements into a well-coordinated and fully planned strategic project to effect a maximum level of territorial control, using the most rudimentary element of domestic space: the single-family detached house.

2 Eyal Weizman, “The Subversion of Jerusalem’s Sacred Vernaculars,” in The Next Jerusalem: Sharing the Divided City, ed. Michael Sorkin (New York: Monacelli Press, 2002), 132.

3 Yehezkel Lein and Eyal Weizman, Land Grab: Israel’s Settlement Policy in the West Bank (Jerusalem: B’tselem, 2002).