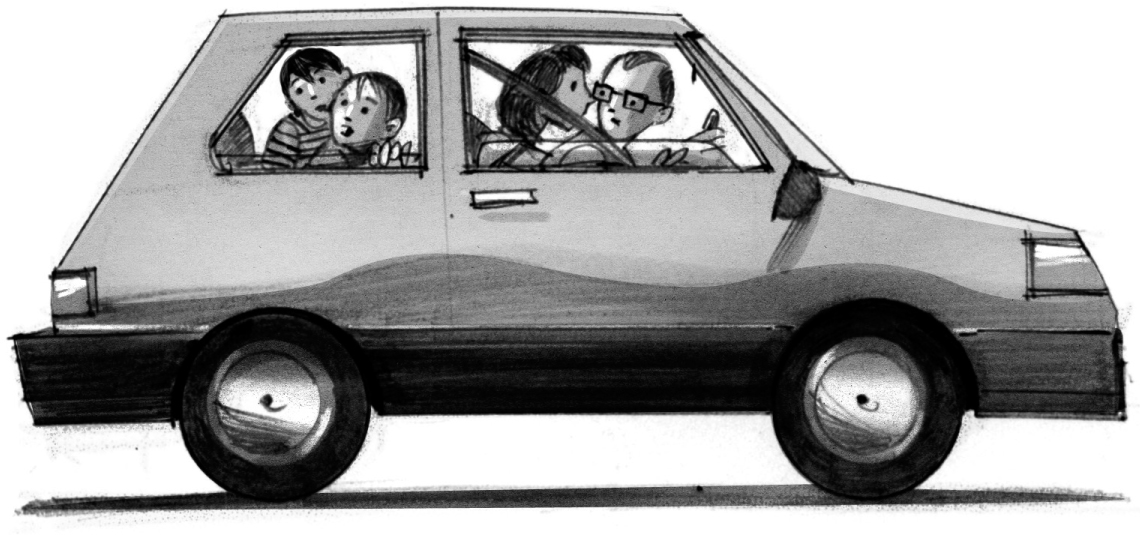

Columbus Circle was totally jammed with cars, buses, and taxis. That made me panic until I realized that if we were going slow, then the men chasing us were probably going just as slow.

Dad tried his cell phone again, then snapped it shut with frustration. “Everything is going to be fine,” he said, but there wasn’t more than an ounce of confidence in his voice.

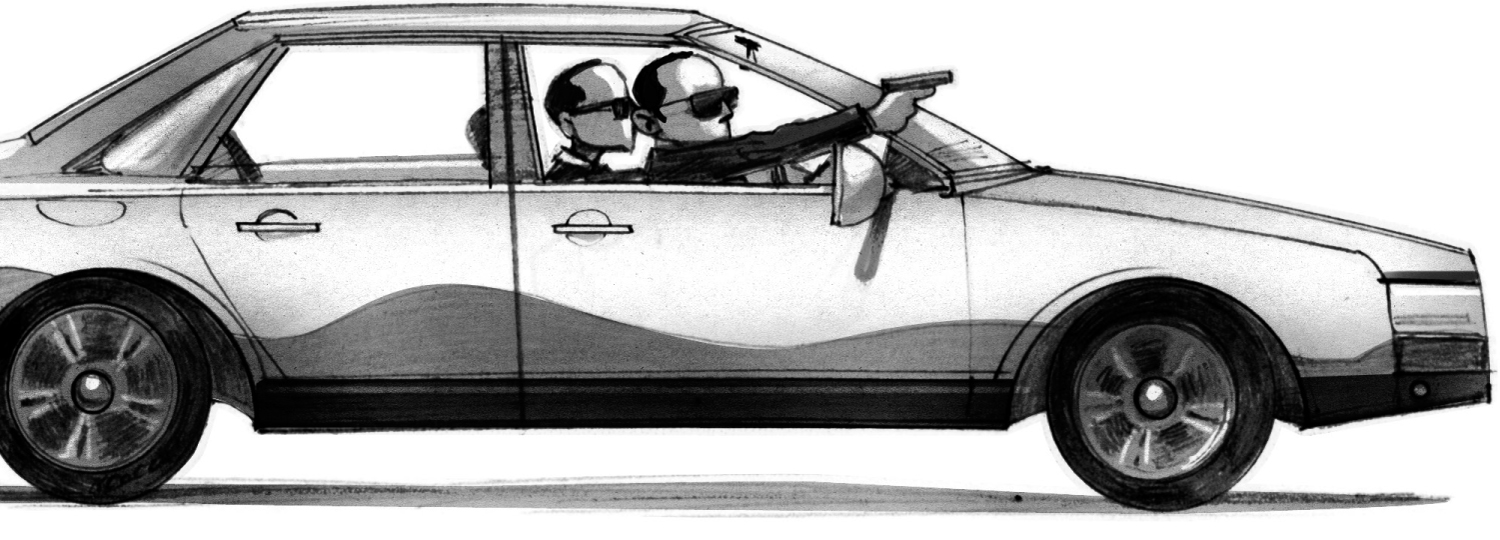

And that was when a silver Audi wedged its way between a taxi and us. It was the two guys, the spies! Their right front window lowered, and I found myself looking at the cold eyes of one of the men. He quickly flashed a gun, then put it somewhere below the window. A gun! It was a gun! I was so frightened I even forgot to duck.

“It’s them!” I shouted. “They’re right next us! The one guy has a gun!”

The silver car then slipped behind our car. Dad peered out the rear window and told Mom to pick up speed.

“I’m doing the best I can,” she said, focusing on the traffic in front of us. “This is worse than rush hour. Why are there so many cars in this stupid city?” She slammed her hand against the steering wheel, then managed to pass a gray SUV. But the driver of the silver car did the same thing. They were still right on us.

I was trying to remember how to breathe.

Dad checked the side mirror, then turned toward Norman and me. “Matt,” he said as serious as a brick. “I need you to leave Norman where he is and climb up front with us.”

“Why?” I asked, sensing that I didn’t want to know the answer.

“No arguments. Get up here,” he demanded.

My right leg started to shake. I couldn’t get it to stop. “I need to know why,” I said to my dad, my voice going all crazy quivery.

Dad groaned, and told Norman to turn off his hearing. Norman blinked several times and said, “Hearing interface deactivated.”

My dad rubbed his face and checked behind us again—the Audi was still there. “Norman has a voice-activated fail-safe mechanism,” he told me, “to keep his technology from falling into the wrong hands. If certain code words and numbers are said, or typed in remotely, Norman will begin erasing files, then, essentially, implode, making it impossible for him to be rebuilt, or for his data to be recovered.”

My brother was wired with explosives? Unreal! (But it was also kind of cool, in a weird way, having an explodable brother. Enough said!)

“You want to blow up Norman?” Mom asked, slowing down at an intersection. “In the car?!”

“Implode, not explode,” Dad explained. “We should be perfectly safe, though Jean-Pierre and I never had a chance to test it. So the farther away we are from Norman, the better. Get up here, Matt.”

“You can’t blow up Norman!” I said as tears rushed to my eyes.

“I don’t want to!” Dad said, his voice cracking. “But if I have to I will, to protect the technology, and you.” He exhaled and patted at his face. “So please, please move Norman to the floor, as low as possible, then get up here just in case I need to say the code words.”

He meant Lucien’s birth date repeated twice. It somehow dawned on me that Lucien’s birthday could be Norman’s death day. How wrong was that?

I glanced at Norman, frozenly peering ahead, and knew what I had to do. I’m normally not the kind of kid who goes against what his parents tell him, but this was different. This was about Norman.

So I slipped my arm around my brother and pulled him closer. “You are not hurting Norman,” I said. The clueless robot smiled at me. Aggh!

“Matthew!” my father exclaimed, gritting his teeth.

I didn’t budge.

“Do what your father said, Matt!” Mom barked, checking the mirrors. “And where are the police? How can there not be one policeman on the street?” (That’s one of the funky things about living in New York City. When you don’t need a cop, it’s like there’s one on every corner. But when you do . . . Well, it’s like they’re all hanging out at the Donut Shack or something. Or, better, Zabar’s deli.)

“Forget it,” I said, feeling brave and weak at the same time, but knowing with absolute certainty that Norman would do the same for me.

Dad looked like he was about to implode himself, but then he gave a big sigh. “I guess I’d feel the same way if it was my brother who was at risk,” he said, turning away from Norman and me. “Be safe, Jean-Pierre,” he mumbled.

Phew! I sucked in air, then signaled Norman that it was okay to activate his hearing.

“Hearing interface engaged,” the robot said, blinking. “I hope I did not miss anything vital.”

Nope. Just me saving your life, brother.

Mom had to stop at a red light at West 48th Street. That was when the silver car bumped into the back of the Renault. Not a big, thuddy jerk, but more like a tap, like they were sending us a message.

When the light turned green, Mom got a fierce look on her face and floored it, but the Audi drove up beside us, then the man who’d showed the gun pointed out his window and motioned, like he wanted us to pull to the curb, in front of a Thai restaurant. They’re everywhere!

“Do they think we’re crazy?” Dad said. “Do NOT pull over.”

“I know, I know!” Mom shouted. “Matthew, we have to lose them, and quick. We only have an eighth of a tank of gas left.”

While we were all looking for a way out of this mess, Mom suddenly swerved into oncoming traffic, forcing other cars to get out of the way, and punched down on the gas. Ah! This was very dangerous! But it took the spies by surprise—they were several car lengths back now.

Mom then made a quick, illegal turn, causing some pedestrians to give us ugly looks, and a traffic cop to blow a whistle. It was smooth sailing for a block, then we ran into a huge traffic jam outside Times Square. We came to a dead stop. So had the cars in front of us, beside us, and behind us. We were even more trapped than we’d been a minute earlier.

Mom smacked at the steering wheel and said, “What was I thinking? I should have stayed on Ninth.”

Dad, Norman, and I looked back. The silver car was three cars behind us.

“Just stay calm,” my dad urged, but he looked more on the edge of a major freak-out than my mom. And the traffic hadn’t moved.

I peered ahead and saw a crowd gathered, some of them jumping up and down or holding signs. I wasn’t sure what was going on, so I craned my neck and looked up at a Jumbotron, and realized what was happening: It was a live broadcast of the Wake Up, America show, and Fig Ferrell was giving the weather forecast.

Thanks for clogging up traffic, Fig. Jerk!

But then an idea hit me.

A super-big idea!

An idea so huge you’d think it took four brains working together to come up with it. Sure, it was going to be risky, but . . . I had to give it a shot. NOW.

I looked back to make sure the Audi wasn’t any closer—it wasn’t—then undid Norman’s and my seat belts, grabbed his hand, told Mom and Dad, “We’ll be at the studio. Find us!” and slipped out of the car with Norman. As we were hurrying away, I heard Dad shout, “Matthew! Get back here!”

Trust me, Dad. And Mom. And Norman. I took a quick look back. A taxi driver was yelling at the guys in the Audi as they tried to pull into his lane, even though there wasn’t any room. Good! And then two cops were running up to our car just as my mom and dad were slipping out of it. Not sure what was going on, but I thought that we better not go back. The plan I came up with might be the best hope of saving Norman. I had to stick to it no matter what.

Norman and I weaved through the TV show crowd, but the closer we got to Fig Ferrell, the tougher it was to make progress. I guess these people weren’t eager to give up a chance of getting their faces on TV. But we pressed forward with lots of excuse me, excuse me, excuse me’s, and were soon at the front, near the barricade they’d set up to protect Fig from crazed fans.

I think the show was on commercial. Oh wait, check the Jumbotron, doofus. The Wake Up, America show was actually doing a segment inside the studio where Nancy and a chef were making omelets, packing them with all sorts of veggies and cheeses and meats. Yum!

Outside, Fig, only ten feet from Norman and me, chatted with a blond-haired lady wearing a sweatshirt that said GO CORNHUSKERS! Um, okay. Anyway, it was time to activate my plan. Be brave, I told myself.

“Hey, Fig,” I yelled out. “How would you like to meet my robotic brother?”

This got Fig’s attention. He lumbered to us, glancing at Norman and me. “A robotic brother, huh?” he said, squeezing his face into a doubtful look. “So what is he going to do, break out in a robot dance?”

“Not exactly,” I said, tugging Norman closer and lifting up a flap of his neck skin, revealing ports and his power button. A few people in the crowd oohed or said things like “That’s weird,” or even backed away from us a little.

Fig was not impressed. “While I’ll admit that the computer gizmo stuff is peculiar,” he said, “all I can say is good one, guys. Nice job of fakery. But sorry, I’ve seen it all. I’m not putting you on camera.”

He started to leave. Time to crank it up. “Norman, go into hyper robot mode,” I told my brother. “Right now. Show us your mad skills!”

“Oui,” Norman said, grinning. He then did a dozen standing backflips while reciting lines from the Shakespeare play Hamlet, first in English . . .

To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them?

And then he said it in French, which I won’t even bother trying to repeat.

After that, he dropped to the ground and started doing rapid-fire push-ups with one pinkie while explaining the law of gravity and reciting a brief biography of the great Sir Isaac Newton.

Next, the robot folded himself into a ball and rolled toward a flagpole, which he climbed as fast as Spider-Man could—pretty much a blur—while multiplying pi times pi times pi. “Pi times pi equals 9.8696044, times pi equals 31.0062766, times pi equals 97.4090908 . . .”

I didn’t even know what pi was!

Finally Norman descended the pole, rolled close to me, stood, launched himself fifteen feet into the air, and landed in his previous standing spot. “Hyper robot mode fini,” he said, bowing graciously.

The crowd had gone silent, except for those who were madly running away. Fig and a guy wearing a headset were standing in front of Norman and me, their mouths hanging open like they’d just seen a walrus give birth to a monkey.

The man with the headset checked his watch. “We have to get this kid on the show, and quick,” he said. “There are only eight minutes of program time left.”

Fig, still looking goofy-eyed, simply nodded.

As Norman and I were being hustled toward the studio entrance by the headset guy, I looked back in the direction of my mom and dad. I couldn’t see the Renault, or the silver car. I hoped, and prayed, that my parents were okay. Please, God. Please.

Then I remembered my uncle and cousin. The Rambeaus were under attack in two countries. What were our chances?