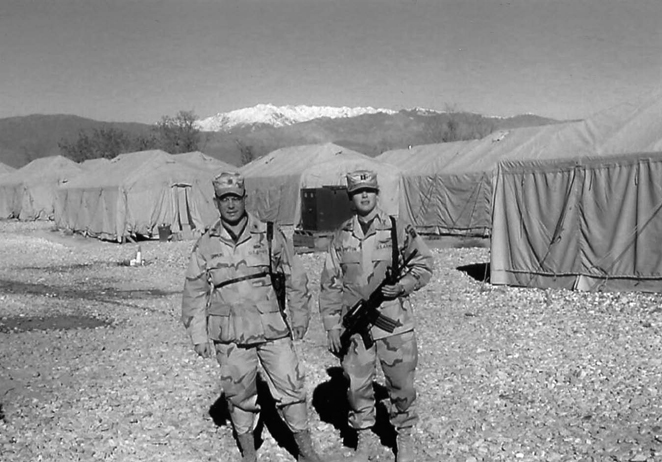

Kimberly and Major Matt Brady before flying on Christmas Day 2002 in Afghanistan.

Kimberly arrived in Afghanistan at Bagram Airfield two weeks before Thanksgiving, on November 14, 2002. Her home for the holiday season was a compound of tents and trailers in a combat zone, where she was stationed with the Coalition Joint Task Force 180 for Operation Enduring Freedom. The perpetually snow capped peaks of the Hindu Kush rose majestically on the Pakistani border in stark contrast with the flat plain where the former Russian air base was encircled by poverty and war.

The mournful wail of the Muslims’ call to prayer lingered in the air daily as people who lived in an adjacent village observed their sacred rituals. Small arms fire punctuated the darkness almost nightly around the perimeter of the base, although few rocket attacks were intentionally fired at the base. Most of the shooting came from local Afghans hunting and, in what seemed to be a common occurrence, locals simply firing shots into the air for no particular reason. Harrier jets, transports, and helicopters flew noisily overhead. There were occasional blasts from planned detonations of explosives by ordnance disposal teams, and every once in a while a land mine was accidentally set off by animals, people or simply time. The dusty air smelled of jet fuel, trash, sewage, coal, and open-air meat markets in the villages.

The base itself was several miles long and about half a mile wide. Thick layers of large crushed rock gravel covered the roads to keep dust down and, more importantly, to make it more difficult for Afghans who worked on the base to plant landmines. Landmines could be as small as a can of snuff, and guards kept a careful watch over the local Afghans who worked on the base. This was war, and the American soldiers could never let their guard down. Kimberly carried either her M4 carbine or her 9mm pistol with her at all times at Bagram, even when she went for her daily run.

The base running track was a dirt road that ran seven-and-a-half miles around the perimeter of the airfield and dead-ended at an airplane graveyard. In dry weather the dirt was like talcum powder and every step stirred up a fine dust. In wet weather it turned to mud and splattered everything.

Kimberly was deployed to Afghanistan because Col. Benny Steagall, the brigade commander, was stationed there and wanted to evaluate her for future command. He liked to handpick his company and troop commanders and took a keen interest in every new aviator captain arriving at Ft. Bragg:

I picked the troop and company level commanders. I size every one up, talk to them, interview them, and approve them before they go into command.

I wanted to know every captain level commander I put in. I knew the war was going to escalate. We were putting captains in charge of troops and pilots, and I wanted them to be very experienced.

She wanted to go to Afghanistan. She was fired up. We were short here and we were rotating folks. I said send her on over here to Afghanistan. We’ll work her here and size her up for command.

I had never met her. She arrived, and in our operations center we didn’t have any females. She was very attractive. I thought, “Oh, my God.” But it was never an issue. As she got into her duties I told her, “You need to jump into some of those CH-47s or Black Hawks.” She wasn’t in the pilot biz, but in a big aircraft like that you can help out the air crew. It’s pretty busy. You need a lot of eyes over there. We just never knew what was going to be shot at us over there. You just never know what’s going to come at you.

She went out and toured the fire bases. She came back smiling and gave me a thumbs up. I knew she had what it takes to lead soldiers in war.

She was a pretty quiet person, and she hung to herself. I would see her jogging up and down the road each day. We had to carry our weapons. We had a secure area where we could do our PT. I’d smile at her as we’d pass. She had her 9-mm in her hand. I said, “Yes, she’s a serious warrior.” Kimberly was the kind of cloth that would have been a senior army leader. She was a trailblazer.

We had a lot of time on our hands and I spent a lot of time with her. She was like a daughter to me. I shared with her an old codger’s thoughts about taking care of the kids, the soldiers, being careful and always knowing that the enemy’s going to come from where you don’t expect it.

Kimberly’s first quarters at Bagram were on the second floor of an old burned-out Russian hangar. It was filthy and there was no heat. The climate was much like winter back home in Upstate South Carolina, and nights in the hangar were cold as ice. Soldiers slept on sleeping bags on top of folding cots that were crowded in everywhere, with blankets hung in between them for some semblance of privacy. Learning to change clothes in the blink of an eye on the tennis court paid off now. People were always coming and going, and uninterrupted sleep was a precious commodity.

Kimberly and Major Matt Brady before flying on Christmas Day 2002 in Afghanistan.

Kimberly was night battle captain for Task Force Pegasus of the 82nd Aviation Brigade. She worked twelve-hour night shifts in the aviation brigade’s tactical operations center (TOC), a trailer on back of an eighteen-wheeler. It was one of numerous trailers permanently parked around a big aviation hangar. From the outside, the trailer looked like a tan box. Inside, it was a high-tech realm. About eight computer terminals, several sets of regular land-line type telephones, and some sophisticated satellite telephones linked Kimberly and others working with her to the battlefield and to army brass around the globe. A television at one end broadcast CNN and other newscasts around the clock.

Our TOC is kinda like the back of an 18 wheeler. We have an enclosed area behind it with a phone, a fridge, and some game tables. Next to the TOC is a TV tent with a computer that we can use to access the internet, a TV with VCR, a DVD player, and a projector and screen—kinda like a big screen—for movies. Next to the TV tent is the “kitchen tent.” It’s stocked with food, snacks, personal hygiene items that folks send from the states. Combat these days is very different than it used to be! Now you guys aren’t going to feel sorry for me being over here in this third world country!

—e-mail from Kimberly to Ann and Dale, November 22, 2002

I just didn’t dwell on the fact that my precious daughter was in a combat zone. I had to put her wishes and desires ahead of my feelings. Kimberly would have been crushed if she hadn’t been able to go to Afghanistan. There wasn’t a day that she was gone that I didn’t want, from a selfish standpoint, for her to come home and teach English and coach tennis. But I knew she would be miserable doing that until she got ready.

Although it may seem naïve in hindsight, I wasn’t nearly as worried about her in Afghanistan, where she had a desk job and wasn’t on the front line herself, as I was when she was in Korea flying on the DMZ. I also knew this would be a relatively short deployment compared to the two years she was in Korea. We didn’t know exactly how long she would be in Afghanistan, but at the time the deployments typically lasted only a few months, not the twelve to fifteen months seen later in the war.

I was concerned about communications. We had been told that the only way the troops would be able to call home from Afghanistan was to call to a local military line. They couldn’t call directly to civilian phones. I worried over the prospect of possibly going for long periods of time without hearing from Kimberly. I saw an article in the Easley newspaper about the local county Veteran Affairs officer going to Afghanistan, and it occurred to me that they might have a military line right there in nearby Pickens, a small town about seven miles from Easley that is the county seat. I called the Veterans Affairs office and asked how the Veterans Affairs officer was calling back there from Afghanistan.

I was given the name of an Army Reserve Center in Greenville that Kimberly could call through. I called them and told them who I was and gave Kimberly the information so she could call home through them.

During the phone conversation, I also learned that the Veterans Affairs officer was stationed at Bagram. I asked the woman at his office if she would give him a message and ask him to look Kimberly up.

Major Rick Simmons, the county Veterans Affairs Officer, arrived at Bagram with the 18th Airborne Corps two days ahead of Kimberly. Rick, who was from Pickens, received my message from his office and e-mailed Kimberly right away: “I’m not sure I’ve got the right Hampton or not— are you from Easley?”

It was Kimberly’s second day at Bagram. She responded, and Rick took a break from work the next night and walked to her office, about three-quarters of a mile down the rocky roads, to meet her.

Rick walked up the steep set of steps at the back of the trailer where Kimberly worked and opened the door, pulling it outward onto the small landing. When he walked in, Kimberly and two other soldiers working inside instantly popped to attention because Rick, a major, was a superior officer. Kimberly flashed her trademark smile and it made a lasting impression. “When Kimberly stands at attention, she beams with that brilliant smile of hers,” Rick later wrote of her in a memorial tribute for the local newspapers.

We hit it off real well. I would see her about once a week. When I’d get the Easley Progress and the Pickens Sentinel, I’d always take them to her after I finished reading them. She was an only child and I’m an only child. Because you don’t have siblings, sometimes you form a relationship in the community that you would otherwise have with a sibling. We would often talk about going to Joe’s [a popular ice cream and sandwich shop in Easley], and eating. She liked grilled cheese sandwiches and French fries, and of course I wanted my hot dog. We talked about people we knew. She’d tell me about her grandfather who was in the Marine Corps. Her dad was a big football player in Easley High and she and her dad are in the Easley Athletic Hall of Fame. I have a step-sister who’s in the Easley Athletic Hall of Fame. We had a lot of stuff in common.

Kimberly and Lt. Col. Rick Simmons at Bagram Airfield in Afghanistan. Courtesy of Rick Simmons

Back home in Easley, it helped Dale and me to know that Kimberly had someone from home who could understand her and where she is from, who could look out for her over there.

“Thank you so much for visiting Kimberly, and thanks too for your kind words and offer of help,” I e-mailed Rick Simmons. “Yes, we are very proud of her, and have reconciled ourselves to the fact that she’s doing what she loves!”

Kimberly had been at Bagram several days before we received our first phone call from her, patched through from the Greenville Army Reserve Center.

“Mrs. Hampton, I have your daughter on the line.”

Aside from hearing your own child’s voice on the phone, those were the most wonderful words in the world to a parent of a soldier serving overseas.

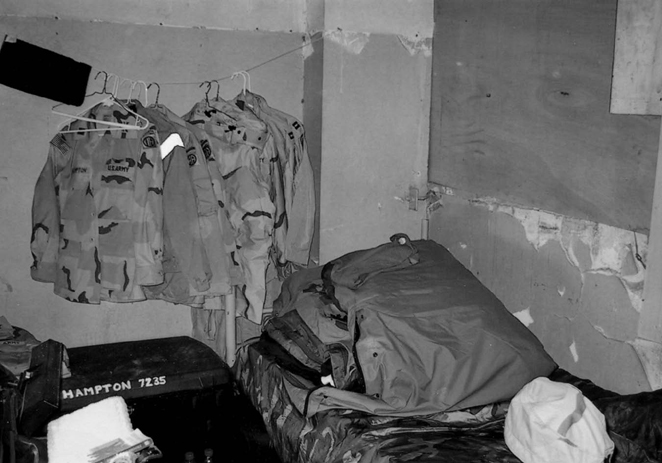

Kimberly’s sleeping area at Bagram Airfield in Afghanistan.

It wasn’t long until she had e-mail contact, so we didn’t have to use the telephone too often. She got a web cam that she could set up on her lap top, and we had a web cam so we could see her and she could see us. There was usually a time delay, so the quality wasn’t very good and sometimes the system would hang up, but just to be able to catch a glimpse of her meant so much to us. We had talked on e-mail while she was in Korea, and we had a web cam so she could see us and Tiger, her cat, but we couldn’t see her. Being able to see her helped so much. At times I saw excitement in her eyes, at other times I saw exhaustion. Being able to see her sweet face and her beautiful smile meant more to me than words can express, and told me more about how she was doing than words ever could.

Kimberly loved the night shift where there was more action than paperwork. Most combat took place at night and there was some contact almost nightly. As the battle captain, Kimberly tracked everything going on in missions. Kimberly never shared many details of exactly what she did at work with Dale and me. I know she didn’t want to worry us. Lieutenant Colonel Mathew Brady, who was at that time a major in command of the 1042nd Medical Company, the air ambulance, described her role as “the eyes and ears of the commander in the tactical operations center when he’s not around.”

In medevac, we work 24/7. So if we got a nine line—there’s nine lines of information that we take for any medevac: type of injury, equipment needed, location, all that kind of stuff - if we got a nine line, then Kimberly would wake me up and then we would go to work. She really became our babysitter, if you will, in that she manned the TOC and we would be out there flying. Her radio operators and her other staff people would be tracking us, where we’re going and what we’re doing all the way from the time we left Bagram until the time we returned. She became that voice on the other end of the radio that got us home.

Captain Jason King, who grew up in Westminster, South Carolina, about half an hour from Easley, was the day battle captain, doing the same job as Kimberly, but on the day side. Like Kimberly, he flew Kiowas and also was a new captain. They briefed each other twice daily when one came on duty and the other went off:

During your shift you have a plan and track missions as they’re going on and let the Brigade Commander know the situation if there’s anything going on and what the plans are for the next twenty-four to forty-eight hours. Kimberly and I had to not only talk as far as the job, but we had to be pretty close. We worked twelve to fourteen hours, it depends, because something always happened when you were trying to turn the shift over. We talked a couple hours each day. It was mainly about business, our job. It was pretty stressful being in a combat environment. It was both of our first experience in combat. We definitely put 100 percent into our jobs.

Besides the fact that I knew where she grew up and we flew the same aircraft, I could tell from the first couple of times that I met Kimberly that she was the type of person that I was going to like and that I was going to respect. She was phenomenal. I was very impressed with her professionalism, when she was doing her job, and even when it was just two captains talking.

By Thanksgiving, Kimberly had settled into the routine and had made herself at home in her new surroundings. When Rick showed up at the trailer the night before Thanksgiving with a Thanksgiving card and a care package of near beer, a non-alcoholic brew, she thanked him in an e-mail and by now was comfortable enough to put on her “mother-hen hat” and chide this senior officer in an e-mail for not dressing warmly enough for the walk across the base:

Sir … you really must start wearing a jacket when you go out for late night jaunts—it’s cold out there! Thanks for making the walk down—know that wasn’t easy in the dark! I haven’t fallen yet, but I’ve come very close. Hope you have a great Thanksgiving Dinner tomorrow—I think anything will be better than the standard scalloped potatoes and vege-all!

On Thanksgiving Day, Kimberly, as a young, rising officer, was invited to be part of a group eating Thanksgiving dinner with army chief of staff Gen. Eric Shinseki.

“Not sure he imparted any wonderful words of wisdom, but I was impressed with how he answered questions and addressed issue,” Kimberly later e-mailed Rick. “There was no rhetoric … just plain talk, which was what we all wanted to hear. We talked about AH-64 tactics, aviation maintenance and maintainers, ROE [rules of engagement] (crossing the PK [Pakistan] border), and the frustrations of depending on the AF [air force] for so much of what we do here.”

The dinner lasted about an hour. The occasion “was enlightening, but the food didn’t taste great,” Kimberly e-mailed Rick. The processed turkey was as far from her mother’s cooking as Bagram is from Easley. “I’ve decided that I might as well just start eating for sustainment, instead of getting my hopes up that the food is actually going to taste good. I spent two years in Korea … I’m sure I can handle 4 months of the field DFAC [dining facility, what used to be called the mess hall]. I wanted to lose some weight over here anyway!”

She ate better the next night.

“Major Sexton scored a real live pizza from a Pizza Hut somewhere that the AF flew in tonight. Think it came from Doha, Qatar. There was a little Pizza Hut trailer there. Was nice to have real live pizza again,” Kimberly e-mailed Rick. “Think my first meal when I get back will be greasy Papa John’s pizza and a cold beer! I’ll have to call my parents in advance and have it waiting when I get off the plane! Thoughts like that aren’t very comforting over here … I try to not think about the food too much. Just makes me want to get home that much more.”

Kimberly gave some thought to her future back home as well:

“Would love to have my own helicopter—definitely can’t do that on an Army salary, though. Would also be awesome to fly for a sheriff’s department, but I suspect I will never have enough experience to even be competitive for a job like that. Usually those jobs go to ex-warrant officers who flew thousands of hours in the military.

“I’ll be doing good to just break 1,000 myself,” Kimberly wrote in an e-mail.

The Pickens County Sheriff’s Office has a helicopter, and probably could use another pilot, Rick told her.

By the middle of December, the relative autonomy of Kimberly’s night shift came to an end when Jason’s tour in Afghanistan was over and he returned to Ft. Bragg. Taking over the day shift would give her more responsibility and visibility, “but it won’t allow me the freedom to come and go as I please during the daytime hours,” Kimberly wrote to Rick.

Working dayside, Kimberly was responsible for a lot of briefings. Her day started early with a shift change brief from the night battle captain. Then she had to review any changes that occurred overnight and update several PowerPoint presentations and a fourteen-day calendar of flights in the brigade before she went to breakfast.

Then there were mission requests to review and determine what could and couldn’t be supported, and flights to coordinate with the task force in Kandahar. More meetings followed, with the task force at Bagram to work through mission support plans for the next seven days and air mission coordination meetings. Then she met with the brigade executive officer, Maj. Mike Pyott, to see what information came out of meetings he attended and change schedules and coordinate as needed.

Throughout the day she tracked departure and arrival times for all sixty-five Task Force Pegasus aircraft in the country and stayed busy putting out fires and getting necessary information passed along up and down the chain of command. Sometimes late in the shift there was time for PT, but not always. She ended her work day preparing PowerPoint slides for Colonel Steagall’s update brief and the shift change briefing. She also prepared slides on the day’s missions and upcoming missions for Major Pyott who remembers:

She got to the brigade right after I moved up to be XO. At that point we kind of knew we were going to be deploying the aviation brigade to Afghanistan, and we were trying to beef ourselves up with personnel. She showed up and we pulled her into the brigade S3 shop.

Normally when someone new shows up, it takes them quite awhile to figure out the unit, to figure out all the procedures and the personality of the unit and of the commander and just generally how things work. Most people show up and they’re quiet and subdued and they’re looking to see how things function before they really jump in and start putting in a lot of energy into fixing things and trying to improve the unit. Kim was one of those who jumped right in and was figuring things out very quickly and was contributing to a lot of things right up front. That was very key to making sure we were getting all the things done to start deploying the headquarters. She kind of ended up acting as the S3 when the actual S3 was forward. We both went over in November. She went over a couple of days ahead of me because she got stuck in, I think it was Rhoda, Spain, on her way over, and I got stuck in Kyrgyzstan. It was one in the morning when I showed up in Afghanistan, and my body at that point didn’t know what time zone it was on. We had spent three days in Kyrgyzstan and then we flew into Kandahar and we caught a flight from Kandahar up north to Bagram. When I walked into the brigade operations center, Kim was on duty. She was wide awake and had a big smile.

“Hey, welcome to Afghanistan, good to see you!”

She had jumped right in when she got there and was already assuming the job of battle captain. Typically the battle captain is the officer who is really running the operations center and in charge of making the on-the-spot decisions for headquarters. It’s their job to determine if they can make the decision as to whether or not something needs to happen or if they need to get the commander or someone with more authority. We place a lot of trust in our battle captains. Some people can do it very well and some people need to have a lot of oversight. Kim was one who immediately jumped in and established herself with her maturity, so they used her as a battle captain immediately.

Kim really became my lead officer in terms of everyday supply and coordinated all the ring routes: basically aviation routes to transport people, equipment and supplies between all the different bases. Everyday there are coordination meetings to determine which route has to be run and what has to be moved. It’s almost like a small FedEx operation.

For someone like me and someone like Kim, who’s used to dealing with attack operations where you’re focused on going and finding the enemy and then shooting them, to deal with moving supplies and equipment and personnel and these logistical type things is very tedious. Army aviation has two sides to it. The attack side, where I’d kind of grown up, and that’s all about going out and finding and killing the enemy. The other side of the army is all about moving U.S. forces to go find the enemy and kill them. Kim jumped right in. She took control, and immediately started doing all the coordination for those meetings and running them. I give her a lot of credit, as a young captain, quickly figuring it out. That was her meeting that she ran every day as well as doing the battle captain duties throughout the day in the TOC.

The animated PowerPoint presentations Kimberly prepared showed air mission action across the entire country. She had to produce a lot of different products immediately on request, often within minutes. If she was lucky, she might have an hour or so at the most to produce projects. It didn’t matter how difficult the assignment was, she’d look Colonel Steagall square in the eyes and say, “I can handle it, Sir.”

Kimberly was “rock solid confident in her abilities and herself,” Colonel Steagall said. “She could stand up and brief very senior level officers and didn’t show a quiver.”

“I stay busy but it’s rewarding,” Kimberly wrote in an e-mail describing her daily activities to Dale and Ann.

Eventually Kimberly got to move to the canvas tent housing that most soldiers lived in at Bagram. The tents were lined up in neat rows of light tan interspersed with occasional dust-covered olive greens that interrupted but hardly enlivened the drab pattern. The large canvas tents had wooden frames and floors that felt like they were about to take flight themselves whenever the Harrier jets or helicopters passed overhead. Nights were cold, but it was comfortable inside the tents as long as the generators worked.

One of the other captains who enjoyed woodworking made bunk beds out of plywood for Kimberly and some of the others. Her sleeping bag was on the bottom bunk. The top bunk was basically just a plywood shelf where she could keep her belongings off the floor, which was pretty dirty. At the head of the bunk she had a homemade closet with a pole across it where she hung her uniforms. She placed pictures of Will across the top of the closet. At the foot of the bunk she had some shelves.

Most of the soldiers had some type of homemade or locally-made bookcases or shelving that provide storage and a cubicle type wall to separate sleeping areas, and one or two plastic chairs like the ones you’d buy at the Dollar Store back home to put around a back porch picnic table, except these chairs were purchased from a nearby Afghan marketplace. Living in the tents wasn’t exactly the Holiday Inn, but compared to the hangar it was the Ritz.

After the hectic workday, Kimberly was part of a group of officers, all captains and majors, who ate dinner together. They walked to one of the two mess halls on the base and took their trays back to the aviation brigade to eat with the other aviation officers and enlisted aviation brigade personnel. “It was like having dinner with your family because everybody always ate together, almost without exception,” said Matt Brady, the major in charge of the medevac, who was part of the group. Everyone sat around a giant picnic table and talked and ate barbecue steaks or hot dogs, “whatever we could get our hands on” and shared goodies from home. But the staples were chow hall food: mostly scalloped potatoes, chicken cordon bleu, green beans and salad.

After dinner they often watched television programs taped and sent from family and friends back home in the states. Every Tuesday night they watched The Sopranos and every Thursday night after dinner they watched Band of Brothers, a story about the army’s 101st Airborne Division in World War II.

The episodes were “about thirty days old but to us it was all good,” Matt said.

Just before Christmas, the night of December 20, Sgt. Steve Checo of New York, a young man in the 504th Parachute Infantry regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division was killed in battle near the Pakistani border. Kimberly was working when the call came in. Medical and combat helicopters were coordinated and prayers were raised to try to save the young man’s life, but later the troops lined up along the road to the airfield and saluted as a color guard and a Humvee transporting the casket passed by. The procession moved by slowly. The troops watched until the casket, an aluminum transport case covered with an American flag, was ceremoniously loaded onto a waiting aircraft and Sergeant Checo began his final journey home.

It was the first time that either Kimberly or Rick Simmons experienced a combat death and they talked about it afterward:

Not that we were there on the scene, but we were both on duty in our respective operation cells, knowing what was going on. As operations officers at night, we’re following the battle. Her unit’s tracking certain things and where I’m at we’re tracking certain things. They don’t talk on the radios any more. Everything is on e-mail, like Instant Messages. You can read what’s going on and what people are doing, so you can virtually track the battle. You’ve got a big map showing where everything’s at. The call for troops contact comes in, so we know there’s a fight going on, then we hear the medevac. They got him back to Bagram Airbase. He’d been shot in the back of the head.

She and I went off duty, and when we went back on duty that night we found out that he’d died. That night we went down to minimum manning in all the operations cells. They had a Color Guard and we all stood at attention. I was there and Kimberly was there. He went by—the transfer case draped with an American flag. They loaded him up in an airplane and the airplane took off. That was the first guy she and I ever saw killed. We talked about that. It could have been just as easily one of us.

Kimberly told Rick if anything ever happened to him she’d see that his name went up on the War Memorial at the Pickens County Courthouse back home. They talked about seeing that each other would be remembered.

Pickens County has the distinction of having more Medal of Honor winners per capita than any other county in the nation. When the Pickens County Courthouse was expanded in the 1990s, the War Memorial, with a statue and plaques, was built just to the side of the main entrance. Two years later, planning a ceremony and putting Kimberly’s name on that monument would be one of the most painful tasks Rick ever faced.

Kimberly had a desk job, so any flying time she managed to get was special. Kimberly and Major Pyott had the opportunity to fly an Apache mission that he said was a highlight of their time in Afghanistan because they got to fly the aircraft instead of just being passengers:

The danger with most staff [officers] is that we end up getting wrapped into meetings and planning and so forth, and we never actually get out and see what it’s actually like to fly in the terrain that we’re trying to plan operations in. Normally it’s very difficult for someone not qualified in the Apache to fly in the aircraft because it’s considered a two-pilot aircraft, so both pilots are supposed to be trained and qualified in the aircraft. I don’t know what magic they made work, but we went out and flew with the standardization instructor pilot and I think each of us got about forty-five minutes flying around Bagram and the airfield. We actually got to fly the aircraft instead of being a passenger in the back. That was a wonderful day.

The Christmas season was filled with long days at work for Kimberly, but she was off duty on Christmas Day. Matt knew it was a big deal for her to get away from the base and fly, so he invited her to go along on a medevac mission.

“Think I may get on a flight out to Salerno tomorrow,” Kimberly wrote in a Christmas Eve e-mail to Rick. “We have a couple medevac aircraft that are flying out with Warlord 6 and I think they will have an extra seat. Will be kinda like my Christmas joyride!”

It snowed on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day dawned with a light dusting of snow on the ground. There was a Christmas dinner and a Secret Santa gift exchange, but flying with the medevac mission really made the day special.

They flew to Salerno, a forward operating base (FOB) in the Kowst province, about forty-five minutes from Bagram. Thick snow draped the mountainous Pakistani border, but the scene Matt described was no Christmas card picture:

The mountains are gorgeous, but this is a third world place. The only buildings you see for the most part are mud huts; everything there is just mud. Once in a while you’ll see a really beautiful mosque that will really stand out. There’s no electricity, they carry water, they build fires in a pit in the middle of their huts, and that’s how their families cook and heat and live.

We had gone up there to get a patient, but they weren’t ready to come back yet, so we had about an hour to kill. We walked outside the front gates of the FOB and went to the market; these little trailers that the locals have taken over and put all their goods in. [Kimberly] bought a little blue burka, the traditional dress for Afghan women.

The medevac missions Matt flew involved local nationals, particularly children more often than wounded U.S. soldiers. One night after the staff meeting, Kimberly accompanied Matt to the hospital and he walked her through the intensive care unit:

It tore her up to see kids that way. It hurt all of us. We were constantly picking up children that hit a land mine or were playing with an explosive and it blew up or fire victims, snake bite victims. That really affected Kimberly a lot. It’s hard to see that kind of stuff. It’s one thing to see soldiers of either side hurt like that because that’s what you expect out of war, but kids don’t deserve that. They just got born into it.

New Years was tough for Kimberly, who fought a wave of homesickness:

I woke up not feeling well this morning and just continued to feel worse throughout the day. Drank lots of water and hot tea. Ms. Han used to make me tea with sugar and lemon in Korea when I wasn’t feeling well and it always made me feel better. I needed some of that today. … Someone had to remind me that today was New Year’s Eve. It’s just another day here. I have a hard time keeping up with which day of the week it is. If I didn’t work with a flight schedule all day, I would really have a hard time keeping up. It’s time to start counting the days until I leave now. I’m getting ready to get home. Looking forward to getting back into my old routine, where there is a designated time for PT and I get to come home to my sweet kitty every night. I miss cuddling with her. —e-mail from Kimberly to Dale and Ann, December 31, 2002

The perimeter of the Bagram Airfield took small arms fire almost nightly. The Afghans erected little stakes, similar to the stands people use to hold fishing poles along the lakeshore here at home, and launched Chinese rockets from them. Alarms would sound on the airfield and everybody reported to assigned places in three-sided barrier type cement bunkers to wait it out. But toward the end of January, rockets hit Bagram in a more frightening attack.

“We got bombed one night. It was like two or three in the morning,” Matt said. “Most everybody was asleep. They sounded the alarm and everybody ran to their bunkers.”

One of the rockets landed a yard short of Rick’s tent, and another exploded near another tent area. Although they were in a war zone, attacks like this were rare.

“I said a prayer thanking God for the poor gunnery skills of our enemy and for sparing our lives that night,” Rick later wrote in a letter to the local Pickens County newspapers.

By the end of January, Kimberly’s tour in Afghanistan was nearing an end.

We’re finally able to take a breather now that our replacement unit is here. They arrived last week and are now pretty much running the show. … Their eagerness is refreshing, as most of my unit has been here longer than me and they are tired and ready to go home. … So now I’m enjoying taking naps in the middle of the day and doing a lot of reading. … Although I’ve only been here a short time, working 12 or more hours every day was getting old. I’m ready to get back.

—e-mail from Kimberly to Rick, January 26, 2003

We were ready for Kimberly to come back home, too, but we also knew she loved her work. We worried and we prayed, yet we also knew she’d chosen her own path and found happiness there. As her workload eased and she had time to reflect, she shared her thoughts with us in a February 4 e-mail that we will always treasure because it affirms her joy in the life she chose:

You don’t still worry about me do you? Nah! Can’t imagine I give you much to worry about…I mean, volunteering to go to an airborne unit and jump out of airplanes with only thin material to slow my descent to the earth, and then volunteering to go to a combat zone where there are rockets and gunfights and land mine strikes everyday. Nope. … not a thing in the world to worry about. And that’s not to mention my chosen profession, which is to fly a single engine helicopter which is overweight, outdated, and slow. No, nothing to worry about!

If there is anything I can say to ease your mind. … if anything ever happens to me, you can be certain that I am doing the things I love. I’m living my dreams for sure living life on the edge at times and pushing the envelope. But, I’m doing things others only dream about from the safety and comfort of home. I wouldn’t trade this life for anything—I truly love it! So, worry if you must, but you can be sure that your only child is living a full, exciting life and is HAPPY!

Thank you for always supporting me. I love you.

Kimberly

Kimberly landed at Pope Air Force Base, adjacent to Ft. Bragg, back on Carolina soil late at night a few days later. She was exhausted. She had dark circles under her eyes, which was the dead giveaway when she was tired. Dale and I were standing in a big room at what they call Green Ramp. It seemed to take forever from when we spotted the plane in the distance until it landed on the tarmac. Then the customs officials went on board and it took forever again until everyone came off of the plane. The building was flooded with a sea of soldiers. They all looked the same. We were standing up on benches trying to pick Kimberly out. Finally I spotted that beautiful smile. I think we spotted each other at the same time. We all three had happy tears that she was home safely. As exhausted as she was, she was a beautiful sight to our eyes. It took a little while to get the trunk and bags, so we were all exhausted by the time we got her home, but not too tired to have pizza. We had Papa John’s pizza waiting at her house. She reveled in a long, hot shower, we ate pizza and she went to sleep with her kitty. Our baby girl was home.

Kimberly e-mailed Rick a couple days later:

The journey home wasn’t bad. … We stopped in Turkmenistan, Germany, and Canada on the way back for fuel, so I added three more new countries to my “been there, done that” list. I was able to sleep quite a bit on the flight and it was relatively smooth, thankfully.

My parents were at Green Ramp waiting on me when I got back. Sure was good to see them there! Actually didn’t get out of Bagram until late Saturday night (Zulu time). That put us back here late Sunday night (local time). We had a great welcome from the Brigade when we got back.

I’m going through my bags and washing, washing, washing everything. Heading to Easley next week and I will give your dad a call when I get into town. I heard things are heating up again over there. Keep your head down! Let me know if you need anything.

Take care! Kimberly