Kimberly in formal mess uniform.

Kimberly hadn’t flown a Kiowa helicopter since Korea. The small aircraft weren’t used in Afghanistan then because they don’t function well in high mountain altitudes.

Kimberly had accompanied a few missions in other aircraft, but for the most part she had been tied to a desk job at Bagram. Now her feet were back on Carolina soil at Ft. Bragg, and her head was in the clouds. She was flying Kiowas again. Dale and I were up in the clouds, too. Kimberly was just a few hours’ drive away.

During the day, Kimberly worked for Chief in the aviation brigade operations office, back at the same job she had before her deployment to Afghanistan. Jason King, the day battle captain she’d worked with at Bagram, was also an assistant S3 for Chief, so now they worked together on the same shift. The stress of life as a battle captain in a combat environment was gone, but they were always busy. Cavalry troops were constantly redeploying to Iraq and Afghanistan, and their job was to make sure the troops and equipment all got to where they were going.

JASON KING—

As half the unit was coming home, we were busy sending the other half back over. We were very macro-level planners. We made sure that we had the air force lined up to accept our aircraft and to get our people and our equipment. We dealt mainly with the air force operation in Charleston getting that set up. Our units that were being deployed dealt with us. So we were basically the middle man between their air force airplanes and the port operations down at Charleston. Our responsibilities were getting our units deployed to Afghanistan and then to Iraq by the air force, by the navy, or by private ship.

In the evenings after work, Kimberly flew, logging hours in the cockpit to demonstrate her proficiency and become current again. The Kiowa Warrior OH-58D, an armed helicopter, is the most sophisticated model of the Kiowa, and Matt Brady, who returned from Afghanistan to Ft. Bragg shortly after Kimberly, admired Kimberly’s knowledge of the aircraft:

When you’ve been out of the cockpit for a certain amount of time, then you have to go back to demonstrate proficiency and take some check rides to show that you can still do the job. And she has to study the aircraft operations book - there’s all that studying to do on top of work and on top of flying. When you’re away from it you forget stuff, but it’s like riding a bike. Your first couple of times on a bicycle after not riding for a couple of years is not necessarily pretty, but you know how to do it. Once you’ve gotten on that bicycle again and gone a couple times around the block and become real comfortable with it again, then you’re fine.

After flying, she always was ear to ear smiling. Flying was everything for her. There was nothing more important to Kimberly than being the best pilot she could be—and she was. She knew that aircraft frontward and backwards.

Aviation is a man’s game. It’s a good old boy’s club if you will, in that it’s predominantly male. We’re all very A-type personalities. We believe we are the best at everything we do. You have to, to be out flying in combat. You throw a woman into flying, and she’s got to be pretty good. She’s got to be able to keep up with the boys. But you throw a woman into the cavalry flying 58s, which has forever been an all male club, and she has got to be really good. And that’s the caliber of pilot, leader and person that Kimberly was. She could run with any of the guys. Everything she did, she was that good.

This was her world. The spurs, the Stetson, the leather jacket, she played right into this cavalry role - the most difficult job in army aviation, that’s what she wanted and that’s what she did.

Back home from combat, chow hall food and MREs (meals ready to eat: dehydrated combat rations that replaced the C-rations of earlier times) Kimberly was living on a diet of Chinese food, pizza, ice cream, and sushi. She settled into the house she’d rented in Fayetteville after the Captains Course. She hadn’t finished unpacking her moving boxes before she went to Afghanistan, and never did get it all done before she deployed to Iraq. Her day started with PT in the morning with the aviation brigade staff. After work she went to a women’s gym and worked out some more before flying. After flying, she studied the aircraft operations book and emergency procedures to review material she’d forgotten while away from flying, while her cat, Tiger, purred in her lap. Dale and I kept Tiger for Kimberly while she was in Afghanistan. I think Tiger was as happy as we were to see Kimberly when we brought her back up to Fayetteville. One day Kimberly told me she’d found a bird’s nest in a hanging plant on her porch. She was watching for eggs and babies. Life was good, but the world was about to change again.

U.S. and coalition forces attacked Baghdad on March 20, 2003, a night of shock and awe. It scared me to death to think that this would likely put Kimberly back in harm’s way. I never shared those feelings with her. I knew that if she didn’t get to go she would be extremely upset, and I just had to accept the fact that she was doing what she wanted to do. I tried not to think about it. I didn’t want to act upset in front of her. I wanted to be as strong about it as she was.

For her part, Kimberly was very military and matter of fact and reserved about her feelings on the new Operation Iraqi Freedom when she talked to Dale and me. But she shared her eagerness to serve with friends.

Captain Robin Brown, who crossed paths with Kimberly at Ft. Rucker in the Captains Course, had been in Iraq during the initial invasion. Back at Ft. Bragg a few months later, she heard Kimberly and others discussing rumors that they might be deployed to Iraq. Having been there, Robin wasn’t very excited about the prospect, but Kimberly was.

“I’ll be the first to go,” Robin recalled Kimberly saying. “There was no question that was something she wanted to do,” Robin said.

By then Kimberly knew that if she went, she’d go as a cavalry troop commander.

I’m taking command of D Troop, 1-17 CAV… You can imagine how excited I am! I am staying busy flying, getting ready for inventories and still working my assistant S3 job at Brigade.

—April 24, 2003, e-mail from Kimberly to Rick

Kimberly had approached Lt. Col. Terry Morgan at Ft. Bragg the previous fall before she deployed to Afghanistan and told him she wanted to serve with his cavalry squadron. He was impressed because it’s uncommon for a squadron commander to be approached with that kind of request. It’s especially unusual from a woman. There are few female troop commanders in the cavalry, an elite, close-knit, traditionally male organization. Lieutenant Colonel Morgan recalled that conversation months later, in the spring of 2003. He was in Kandahar, Afghanistan, and Colonel Steagall contacted him and said he wanted Kimberly to command an airborne cavalry troop.

Change of command was coming up in June for Lt. Col. Morgan’s Delta, “Darkhorse,” Troop. Kimberly had the qualities he wanted but not the credentials for command. Her missing paratrooper qualification, which had been cancelled due to her hernia surgery, was the problem. According to Lieutenant Colonel Morgan:

You have to have the right qualifications to serve in my unit because we no-joke go to combat. She’s at Ft. Bragg, home of airborne. Ninety percent of the population is airborne qualified. You can’t come in and try to lead airborne troopers who have to jump out of airplanes and you not doing it yourself. You’ve got to do it from the front.

The brigade commander [Colonel Steagall] was saying, “Terry I think she’s one of the better of your choices and I want to put her in your squadron.”

I said, “Sir, I do not agree with you.”

At the same time Kimberly shoots me an e-mail in Afghanistan. “Sir, I would really like to command in the Cavalry. I want to be a commander in your Cavalry squadron.”

None of the other captains who were being considered even sent me an e-mail at this point. They’re all talking to the big guys, the brigade commanders. I sent her an e-mail back. “You’ve got to get Airborne qualified first. I have no reservations that you won’t go to Airborne School and qualify. I look forward to having you command in my cavalry squadron and I have no doubt you will succeed.”

I really put some pressure on her to make her perform at a high level. I was doing it because I knew the battles she would have to deal with and I wanted her to come armed with all the credentials.

Lieutenant Colonel Paul Bricker was in charge of the Kiowa Warrior troops still at Ft. Bragg while Lieutenant Colonel Morgan was in Afghanistan. He’d been a battalion commander in Kandahar while Kimberly was at Bagram. He had seen Kimberly’s work in Afghanistan and knew she would make a good commander:

Kimberly was a very effective communicator, whether it’s verbal or writing, whether she was giving briefings, she had a knack of being able to quickly cut through the issues, to determine what they were and present that information to the group. Kimberly was one of the more effective communicators for Colonel Steagall.

That’s an important trait, especially in the military, because you have to be able to figure out what’s important and then what’s urgent, and Kimberly had that ability. And she was very approachable. She was a good communicator, she was modest, and she had an affectionate personality. She was a very effervescent officer, so the people enjoyed working with Kimberly.

Lieutenant Colonel Bricker liked what he saw in Kimberly, but he shared the concern about her lack of airborne certification. Because of the heritage and history of the cavalry, airborne certification is a must for 82nd Airborne Division leaders:

That’s the 82nd Airborne Division that led the charge in the airborne invasion into Europe in 1944. The 82nd Airborne Division is the point of the spear for America when it comes to putting boots on the ground.

That’s the same Airborne Division that Bush 41 [the elder President George Bush] put on the ground when Iraq invaded Kuwait back in 1990. When you’re assigned to the 82nd, it’s not a matter of if, it’s when you’re going, because they are America’s strategic response force.

She’s a female commander now in a group that is heavily male. The paratrooper lifestyle is a rough one. You’ve got a lot of testosterone in the 82nd Airborne Division. She’s leading a group of men who have made a commitment that they want to serve in that unit. You’re a double volunteer when you serve in the 82nd. You’re a volunteer because you joined the army, and then you’re a volunteer to go to the 82nd. You have to volunteer to go to the 82nd. It’s a special soldier that says, “I want to be a paratrooper.”

I spoke to her a couple times behind closed doors, because these young captains are very excited and eager to assume the role and the mantle of responsibility as a commander. I felt it important as a mentor, as a coach, to be able to talk to these young captains. When you come in as a commander, you are responsible for making decisions that quite frankly can deal with life and death. They are greatly important and you need to have great credibility with your troopers. They need to trust you implicitly because to a large degree, when you deploy in combat, you’re entrusted with their lives—the lives of the sons and daughters of our country.

I also wanted to ensure that she understood the importance of being a soldier who made it a priority to know her people, know her soldiers’ spouses, and understand as much as possible about each one of those soldiers, because to a large degree she was the mother of those kids. Some of them were older than her, but as a commander, she’s in charge of that organization.

It was important that she prioritize her responsibilities to insure that when she took command that she was both mentally and physically ready to go because it’s fast and furious. These soldiers are looking at these commanders and they expect complete loyalty, they expect discipline in these organizations to be maintained and they want a leader that they can trust, that they are willing to follow.

I wanted to make sure that I conveyed that to her and that she understood that. She got it. She understood. You could tell. You got that good eyeball to eyeball contact. She asked me very engaging questions that helped confirm to me that she got it.

Kimberly headed to Ft. Benning for Airborne School with mixed emotions. She was excited about taking command but anxious about the three weeks ahead. She had to get through jump school successfully and she couldn’t afford an injury.

During the first week of the three-week course students learn about the equipment, work on physical fitness exercises and make jumps from short stands. The second week starts with jumps from 34-foot towers. Students wear parachute harnesses suspended from ropes on a cable and get the feeling of a real jump without falling far. Then they progress to 250-foot towers. Their parachutes are clipped to baskets and they are lifted to the top of the tower and then released while instructors talk them through the landing on megaphones. Most jump injuries occur in the landing, so a lot of time is spent focusing on how to conduct parachute landing falls.

When the third week rolls around it’s time for the real thing. Students must make five high performance jumps from jets, land safely and walk off the drop zone before they can graduate.

The first jump is the hardest. As a jumpmaster, Lieutenant Colonel Bricker saw a lot of first jumps:

There are a lot of soldiers doing a lot of praying on the first day of Jump Week. It is really a leap of faith. These kids are in back of an airplane and the airplane is roaring and you’re swaying. The aircraft moves back and forth and the jumpmaster opens the door. It’s loud. You’ve got a lot of soldiers packed in the back of an aircraft and they’ve got all this equipment on, and the jumpmaster’s telling them to stand up and hook up, and they start to realize that they’re really going to exit an aircraft. Some of them start getting sick.

During those first two weeks, we’ve taught them all the procedures so it’s written in their minds. So when they get into that aircraft and the door is opened up and the wind is howling through the aircraft, they pay attention to their equipment and they remember what we’ve taught them and they follow the instructions of the jumpmaster as they exit the aircraft.

There are no atheists on that airplane for the first jump. They are all praying. After they do the first jump, they get a lot of confidence and they are much more aware of what’s going on. That first jump, it’s always been the one that I don’t think any paratrooper will ever forget.

The night before her first jump, Kimberly called her college friend Kelli.

“I’m pretty scared,” Kimberly said on the phone.

Kelli had never seen Kimberly scared

“What are you afraid of?” Kelli asked.

“Of dying,” Kimberly said.

She asked Kelli to pray for her.

Kimberly and Kelli had compared their beliefs about eternity and an afterlife in a running conversation over the years, but Kimberly had never talked about dying, not even when they watched Meg Ryan in Courage Under Fire and Kelli got upset.

They prayed together on the phone. Kelli promised Kimberly she’d continue to pray.

I was praying, too. And worrying and driving. My baby girl had graduated from tennis serves to jumps from jets. I’d missed only a few tennis matches, and I certainly wasn’t going to miss this. I drove from Easley to Ft. Benning to be with Kimberly when she made her jumps. I was still on the road when my cell phone rang. It was Kimberly. She had made her first jump. Her voice was filled with excitement.

“I’m hooked,” she told me.

I was just glad she’d lived through it.

I got to Ft. Benning in time to see Kimberly’s remaining four jumps. I shot video of tiny bodies dropping like rockets in those first seconds after leaving the aircraft until the parachute opened, and then drifting gracefully earthward. I never could tell which one was Kimberly. I got to know an army chaplain whose son was jumping, and I leaned on him for comfort as we watched our offspring make their leaps into the sky.

Chief had planned to go to Ft. Benning and make Kimberly’s last jump with her, but his daughter, Jenna, was born that day. Kimberly bought a ring for the baby girl to celebrate her birth.

Just wanted to let you know that I completed my last jump of Airborne School last night and I will graduate tomorrow morning. I’m glad it’s over! I guess my paratrooping career is just beginning, though … I will be heading back up to Bragg on Saturday and my Change of Command is still on for Monday, 16 June at 1000.

—June 12, 2003 e-mail from Kimberly to Rick

Kimberly graduated from Airborne School at Ft. Benning on Friday of Father’s Day weekend. Dale and I came to the ceremony and so did Will, who had just returned from Afghanistan. Will got back to Ft. Campbell that Wednesday night and drove to Ft. Benning the next morning, arriving in time to have dinner with us the night before graduation. Kimberly was pretty excited to be done with Airborne School and to have what could have been a career obstacle behind her. She didn’t expect it to be much fun, but her excitement about jumping grew over the three weeks. By the end of the course she was pretty motivated and pretty excited.

Kimberly in formal mess uniform.

The graduation ceremony was held at the Airborne Track, a big outdoor training area in the middle of the post where the stands and towers used in the first two weeks of the course are located. Several vintage airplanes that had flown in the D-Day invasion are displayed at the track, and the new airborne graduates receive their wings in the shadows of those aircraft.

Dale and Will and I sat in the bleachers off to the side of the track with other family and friends of the graduation class of more than two hundred new paratroopers. They marched toward the bleachers in formation singing cadences from the training. When the group came to a stop, the commander talked about what they did during training. Before this day they were “legs” and walked into battle. Now, as airborne troopers they would drop into battle with parachutes.

When the time came for the graduates to get their airborne wings, the formation split apart so families and friends could go onto the grounds and pin on the wings on their uniforms. The three of us walked over to Kimberly and I did the honors, and pinned her wings on.

Even as we performed this rite of passage, Kimberly’s mind was already on the next challenge. She was excited to have completed the school but she was looking forward. She was ready to take command.

The two sets of wings on the chest of her uniform, her flight-school pilot wings and the newly earned paratrooper wings, were the outward credentials she needed for that next step, her change of command, which was days away. She would officially take over Darkhorse Troop that Monday at Ft. Bragg.

To celebrate after graduation, Kimberly, Will, Dale and I drove our separate cars in a convoy to our lake house, which was on a small lake nestled in South Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains. It was Father’s Day weekend, and Kimberly gave Dale a Father’s Day card, the last he’d receive from her. The message penned in Kimberly’s neat handwriting inside, thanking both of us for making this a special time in her life, is among his most valued belongings.

Kimberly and Will left early Sunday for Ft. Bragg so Kimberly could get her house squared away before we arrived. Dale and I arrived that evening and we all went out to dinner and spent a quiet evening together before Kimberly began the next chapter of her life, as a troop commander.

Made it back to the lake house in Tamassee last night after driving through horrible traffic and rain the whole way back from Ft Benning. I’m glad the rain held off for the graduation yesterday. I’m off for another long day of driving back to Fayetteville in just a few minutes.

My boyfriend made it back from Bagram this week and was able to come to GA to see me graduate Airborne school. He’ll be at the COC [change of command] as well. I’m thankful for the good timing of these events. … Would love to come jump with your unit anytime! I think I’ve got the “airborne fever” now!

—June 14, 2003 e-mail from Kimberly to Rick

It was a big deal for a female to be taking command of a cavalry troop. Lieutenant Colonel James Viola, who officially transferred the Darkhorse Troop command to Kimberly, had heard good things about her from Colonel Steagall. Less than two weeks earlier Viola had taken over command of 2nd Battalion, and was acting commander of the cavalry troops while Lieutenant Colonel Morgan was in Afghanistan. He liked her attitude. She was serious about her work, fresh out of jump school, and fired up about taking command.

As the morning ceremony started First Sergeant Eric Pitkus, with whom Kimberly had briefly served in Korea, formed up the troopers inside the 1st Squadron, 17th Cavalry, hangar at Simmons Army Airfield. Kimberly, Lieutenant Colonel Viola, and Lt. Brad Tinch, the troop’s senior platoon leader who had temporarily commanded Darkhorse Troop while Kimberly was in Airborne School, came forward.

The First Sergeant handed the troop’s guidon, a small, red-and-white flag representing the unit, to Lieutenant Tinch, who passed it to Lieutenant Colonel Viola. Then Lieutenant Colonel Viola handed the guidon to Kimberly, officially transferring the command. Kimberly handed it back to First Sergeant Pitkus who carried the guidon back to the formation. Now it was time for speeches.

Following tradition, Lieutenant Colonel Viola talked about the outgoing commander’s accomplishments, introduced Kimberly and talked about why she was chosen for the command. Lieutenant Tinch, the outgoing commander, thanked the Darkhorse troopers for their service, and then it was Kimberly’s turn. She spoke briefly about her excitement over the new responsibility, thanked the battalion and brigade commanders for the opportunity to lead. She looked toward us and thanked us and all the family.

After the ceremony we attended a catered lunch for Kimberly’s soldiers, and our family members and friends who had come to see her change of command. All of my sisters were there, as were some of Kimberly’s friends who had taken the time to be with her on this special occasion. There were about a hundred people there. Kimberly was showered with flowers and small gifts. The cake was decorated with a Darkhorse logo drawn in icing from a logo I had enlarged on her computer. Will Braman remembers, “I think what made the day special for Kimberly was having all of her family there.”

Will had some time off because he had just returned from Afghanistan, so he stayed with Kimberly the rest of the week but he didn’t see much of her. Like all new commanders, she worked long hours. Will had expected that. It wasn’t a problem, because that Friday they were flying to Vermont to visit his parents.

Will’s father, a retired army colonel who flew helicopters in Vietnam, welcomed Kimberly as “the newest commander in the 82nd Airborne Division.” Kimberly first met Will’s father in Korea when he came to visit Will and had met his mother briefly at Ft. Campbell a year or so earlier, but this was the first time she got to spend any real time with them. They went hiking in the mountains and to a play. The second day they were there Will took Kimberly to his alma mater, Norwich University, a military college where he received an engineering degree and was in ROTC.

Kimberly in red beret worn by airborne soldiers as she gathers her bags the day she deployed for Iraq.

The weather was beautiful during their stay, and Kimberly enjoyed getting to know Will’s parents. When Kimberly went to Iraq, she and Will’s father e-mailed back and forth about the nuances of being a commander and a pilot in an armed conflict.

Kimberly mentally prepared herself for the day she knew would come, when she would lead her Kiowa Warrior troop into combat in Iraq. She grew quickly in her new role and wasn’t afraid to go to her superior officers with questions as she prepared for the task ahead, and Lieutenant Colonel Viola took notice:

Right off the bat she had a positive and serious attitude. She was serious about her work. She was tactically and technically proficient.

Kimberly and fiancé Capt. Will Braman pose for a picture during goodbyes as she deploys to Iraq.

Her soldiers didn’t question whether she knew what she was talking about. You could just see it in her—“Hey, I put the work behind it, here’s the plan.” I don’t know if she ever slept. She was always going. She did all the stuff you see in good leaders, which is listening, paying attention, following when she needed to follow and leading when it’s time to lead.

Not long after Kimberly took command, Colonel Steagall returned to Ft. Bragg for his final change of command and retirement. As he walked past his troops for the last time, he saw Kimberly’s lips move as she stood at attention in the ranks of officers.

“I won’t let you down,” she said.

He knew she meant it.

When Lieutenant Colonel Morgan returned to Ft. Bragg from Afghanistan on August 5, 2003, he was immediately notified that he needed to get an aviation task force to Iraq in thirty days. The Darkhorse troop would be one of the units going and things started moving fast.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL TERRY MORGAN—

In the thirty days the commander has to tie up ends and build up confidence in the troops. A lot of emotions are going crazy and she’s got to handle that as well as her own. She handled it well.

She had a unique smile, even when times were tough. It had an immediate effect on people and gave them a sense of ease.

One hot, humid August day, Kimberly drove out after work to where Lieutenant Colonel Morgan was watching his son at soccer practice. The sun was still high and the temperature was in the 90s at 6:30 PM; most people would have been happy to stay in an air-conditioned office. Kimberly called on the cell phone and said she needed to bring him some paperwork.

He knew the paperwork was an excuse. She really wanted to talk about the upcoming deployment.

Kimberly arrived in her flightsuit, a one-piece green jumpsuit, and sat on the tailgate of his truck, watching the kids kick soccer balls, and asked his advice on combat and what was ahead.

“I told her I had a lot of confidence in her and everything was going to be all right.”

As they talked, his son came out of the soccer game and kicked a ball toward them. Kimberly hopped from the tailgate and started kicking the ball around with the boy on the sidelines and Morgan watched them play. It was one of those moments that always stuck in his mind: she took the time to pay attention to the child. It meant a lot to his son, too. He always asked about Kimberly after that.

As many of you already know, I am deploying to Iraq. Just wanted to pass along my contact information for the next 6+ months:

CPT Kimberly Hampton

D Troop, 1-17 Cavalry

82d Airborne Division

APO AE 09384

I’ll send updates as often as possible. Best wishes …

August 31, 2003 e-mail from Kimberly to family and friends

More than a thousand soldiers were being deployed, taking along fifty-five helicopters and three hundred vehicles. It was time for goodbyes and for beginnings. Dale figured that eventually Kimberly would be sent to Iraq, but not that soon after returning from Afghanistan, but I was in shock when Kimberly called with the news. I knew Kimberly wanted the opportunity to lead troops in combat, and in spite of my motherly concerns, I knew she was following her dream.

Will and Kimberly had decided to get married, but when Kimberly got her orders for Iraq they decided to wait until she returned from Iraq for an “official” engagement. They’d planned to look for a diamond ring for Kimberly’s August 18 birthday, , but she postponed the shopping trip until after her return from Iraq. She didn’t need to take a diamond engagement ring overseas. Kimberly expected to be in Iraq for up to a year, and Will would head that way himself before long; he had received orders not long after Kimberly to deploy to Afghanistan and from there to Iraq. Although the future was uncertain, they were certain about their plans for a life together.

Dale and I arrived at Ft. Bragg a few days before Kimberly deployed. She was running on adrenaline, keeping late hours at the office to be sure that everything was ready. Her troop was part of the task force but not part of the battalion they were going with, and Kimberly was preoccupied with last minute details.

Her dining room looked like a bomb had gone off. She had everything she planned to take laid out on the floor so she could survey it before packing. Clothing, personal items, and other gear spilled across the house from her living room to the bedrooms, and office.

Leo, Kimberly’s friend from the Captains Course, got back from Afghanistan the day before Kimberly left for Iraq. He was exhausted from the trip but slept little because, like Dale, Will, and me, he wanted to spend every possible moment with Kimberly before she left. The five of us went out to dinner to celebrate Leo’s homecoming and Kimberly’s departure. Kimberly and Leo knew exactly where they wanted to go: to the Japanese Steak House for sushi.

Dinner was wonderful. I had a lump in my throat the whole time, but I made the best of it. This was supposed to be a fun night. Everyone ate and ate, but the waiter forgot Kimberly and Leo’s a la carte order of sushi. Toward the end of the meal the waiter came to the table and asked if they still wanted it. Everyone was already stuffed. Normally we’d have said never mind. But Kimberly was deploying the next day. We waited for the sushi and Kimberly and Leo managed to eat it all. I wondered how they packed it all in.

Kimberly was still packing in the morning and Will helped her while Dale got a bucket of extra crispy Kentucky Fried Chicken and biscuits; I fixed green beans, macaroni and cheese, and sliced tomatoes to go with it. It was a true Southern dinner—the noonday meal is called dinner in the South, followed by supper at night—but Dale wasn’t hungry. The lump in my throat the night before must have been catching.

We ate, Kimberly finished her packing, and we loaded up the cars for the trip to a central parking area where the troops were meeting. Kimberly and Will stopped at a hangar on the way to pick up some laptops and went to an ATM machine. Kimberly sent Dale for a pack of gum.

Dale saw tears in Kimberly’s eyes as they said their goodbyes, but only for a minute. Kimberly told me she couldn’t cry in front of her troops. She was the leader and her troops looked to her for support.

Mom’s final hug as Kimberly leaves for Iraq.

Duffle bags and folding cots by an empty aircraft hangar the day Kimberly and her troops arrived at Al Taqaddum, Iraq in September 2003. Courtesy of Jim Cornell

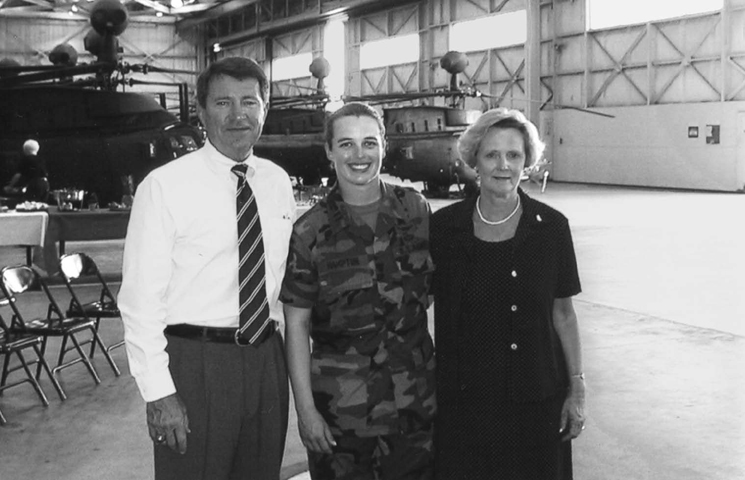

Kimberly with Mom and Dad the day she took command of Delta Troop before leaving for Iraq.

The reality of it hits you. For at least a moment you don’t know if it’s the last time you’ll see your parents. It was good that she had already been to Afghanistan and this was a second deployment. You sit there and look at each other and pray for the best.

I hugged my baby girl, my only child, and tried to pretend she was just going to summer camp. Dale told her to watch over her shoulder and take care of herself, but he had a bad feeling about this farewell. He didn’t say anything to anyone else, even to me at the time, but later he said it did cross his mind that this might be the last time he saw her, that this might be their last hug.

Kimberly handled it like a trooper. None of the rest of us handled it very well, but she did.

Dale looked around the parking lot at all the other families going through the same situation. He felt a kinship with these other people, although most were strangers. He knew they felt the same things he felt.

“Daddy, please don’t go,” a little boy nearby pleaded with his father. The child voiced the words that everyone wanted to say but kept inside.

Dale’s uncle had given his life for his country when he was killed in Normandy on June 19, 1944 almost two weeks after having landed on D-Day on Utah Beach. He never came home from war.

With a confident smile on her face, Kimberly headed to the “cattle cars,” big trailer-type trucks with seats lining the walls that transported the troops to their departure point, away from their families and loved ones.

They were on their way! Kimberly was thrilled, and it showed on her face. Not going would have been like always going to practice but never getting to play in a tennis match, Kimberly had told us. All I could do was watch her go and try to keep my chin up. I understood what Kimberly was trying to say, but this wasn’t just a tennis match or summer camp.

Dale, with camera in hand, chased the cattle car as it pulled away from the parking lot for one last picture. Kimberly wore her camouflage netting-covered army helmet on her head and a smile on her face. Then she was gone.