We learned everything from her, little by little, year by year, long before washing machines, dryers, dishwashers, Quik ovens, new improved vacuum cleaners, and drip-dry clothes. My mother was the hen; my father was the rooster. We were little chicks, we were little helpers. When we came to supper at six o’clock in the evening, my mother would take off her apron and hang it over a chair. She would wipe her hands dry on a kitchen towel, push her hair back a little, sit down at her end of the table, take a long breath in and let out a sigh. She was very beautiful.

My mother, Joan Bridge, was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, the second of two sisters, and raised in the United States. Her mother died when she was only two. Her father was a kindhearted, liberal, intellectual Episcopalian minister who fell in love with domineering women. Mother’s sister Pauline, older by two years, was physically abused by the two women their father married after her mother died. But somehow Pauline grew up looking like a Renoir painting. She was fair-haired, fair-skinned, and full-bosomed, with dreamy but infinitely sad eyes. She would never condemn the mistreatment she had endured, but was endlessly forgiving, paying for her Christian ethics with years of pain and a deep and lifelong melancholy. Mother didn’t get battered so much as she got neglected. She resisted the ferocity of the stepmothers to the point of defending herself physically. Mother was a dark beauty, thin, angular, vampy. She did not know she was beautiful.

Pauline took refuge in books, nature, dance, poetry, and intellectual companionship with her father. Mother took refuge in summer theater, in the woods, at the houses of friends where she would run to hide, and later in Oakwood School, which appears for a short while like a soothing balm in the dark pages of her childhood. And the sisters took refuge in each other.

At eighteen Pauline married a handsome, wavy-haired artist and settled in an artists’ community in Maine. Their father, leaving two more children, was dying of a liver ailment. Mother was living with a succession of foster mothers who cared for her, bought her nice clothes, and tried to bring some normality into her shipwrecked childhood. Mother talks of those days as of a foggily recalled dream. She had no idea of what she would do with her life. She was a leaf in the wind, floating this way and that. With no driving ambition or encouragement from the foster mothers, she did not pursue the idea of becoming an actress. She was catching her breath, wondering what would befall her next, when she met my father.

She was attending a dance at Drew University, on the arm of a young suitor, when (gazing off from the punch bowl, I have always imagined) she spotted a terribly handsome young man—darkskinned, with thick wavy black hair and perfectly white flashing teeth. He was sitting on the school steps amidst a gaggle of attentive and twittering girls, making airplane noises and dive-bombing motions with his hands. Spotting my mother beyond his ring of admirers, he winked at her. She was overcome with shyness and hurried off to control a boiling hot blush.

This young man who was to become my father came to this country at the age of two from Puebla, Mexico. His father had left the Catholic faith to become a Methodist minister and now chose to work with the underprivileged in the States. Albert developed into a bright, conscientious, attractive, inventive, hardworking kid with a deep respect for his parents and for God, and an insatiable curiosity about everything, especially the construction of crystal set radios. He lived in Brooklyn, and when he was nineteen, preached in his father’s church there. I remember visiting his parents in the same dark and spooky brownstone where he grew up. The temperature dropped fifteen degrees as you walked from the front doorstep into the pitch black corridor, which smelled damp and mysterious and strangely like oatmeal. His father smelled of Palmolive soap and had a cozy chuckle, and his mother frightened us considerably because she was very stern. My father started off intending to become a minister, too, but he changed his mind in favor of mathematics and finally physics.

Albert Baez was working his way through school when he met my mother. He drove a Model-T which he had personally rebuilt into a race car.

It was a year after the airplane noises and the wink before Al Baez actually took Joan Bridge out on a date, but the foster mothers had long since been picking out wedding dresses. It must have been like a fairy tale to my mother, the idea of getting married and having a place of her own. Most of all she wanted to have children. I know that she wanted girls. She got three of them: Pauline Thalia, born October 4, 1939, in Orange, New Jersey; Joan Chandos, born January 9, 1941, in Staten Island, New York; and Mimi Margharita, born April 30, 1945, in Stanford, California. Before Mimi came we had moved to Stanford so my father could work on his master’s degree in mathematics. We lived in a beautiful little house across from an open field of hay which was piled into small hills after it was cut. There is a picture of my mother and father straddling their bicycles in front of that field, young and smiling, the sun in their eyes, the wind blowing wisps of hair from my mother’s braids, and across my father’s forehead.

Mother grew sweet peas in our backyard on strings that stretched from the tops of the fence slats down to sticks placed firmly in the earth. I see the neighbor’s mulberry tree whose branches hung down so low you could duck right under them and hide against the trunk, peeking out and staining your mouth and cheeks and hands with mulberry juice. I see our rabbit in his cage over the lettuce rows in the vegetable garden, and the clothesline filled with sheets and tiny dresses, all stuck on the line with wooden clothespins. I see the trees lining the sidewalk in the front yard which bloomed in masses of deep pink in the spring. I would pin clumps of blossoms to my dresses and put them in my hair. I recall one evening when my mother and father were making a fuss over me, holding me up to the stairwell window, exclaiming at the night with its sliver of a moon and scattered twinkling stars. I didn’t know which of them to love the most, and so I hugged my father, and then my mother, and then leaned back over to my father again. Springtime in my chest, and a lucky star on my forehead. That’s what I had in our first California house.

After Mimi’s birth the place was too small, so my mother and father got a job as house parents at the progressive Peninsula School in the same town.

I didn’t want to go to kindergarten because the boys pulled up my skirt, so I began to wear overalls. I behaved badly in class and was put into the cloakroom during milk and graham crackers for clowning and being disruptive. My only real goal was to get home by midmorning and be with my mother.

Since she lived on the property, my escapes were easy enough, and back in her room I comforted myself listening to Uncle Don’s Nursery Rhymes, having lovely tea parties with my dollies, scribbling in my Three Little Piggies book, or helping Mother with chores. Outside I played alone, climbing oak trees, picking and eating the Miner’s lettuce which grew in abundance at the base of the redwood trees, taking my Raggedy Ann for walks.

A short time later Tia (our favorite aunt, Pauline) left her husband and moved out West with her two children. She and my parents bought a huge house on Glenwood Avenue where we could rent out rooms to boarders—as many as five at a time—while my father student-taught and continued to work toward his Ph.D. We had college kids, Chinese scholars, sailors, writers, bus drivers, wanderers, and a cellist who played so beautifully that Mother would click off the vacuum cleaner and stand in the hallway to listen, and I would sit outside his door trying to decide whether to become a cellist in the symphony or to grow long dainty nails.

By age five I was vaguely aware that little children in other parts of the world went to bed hungry every night. I also knew that ants ran around in circles dragging their broken legs if you stepped on one by mistake. I assumed that they were in pain. I imagined that my baby sister, Mimi, hurt when she screamed, but I didn’t care about her the way I cared about the ants and bugs. I was in the practice of pinching the neighbor’s baby. I’d wait till the other kids were out of sight and then move in on the fat little diapered thing sitting in his stroller smelling of baby powder, pablum, and throwup. I’d pat his chubby arm as he flailed it happily up and down, banging his chin and drooling saliva down to the stroller beads. Nervous and excited, I’d give his arm a horrible tweak, then watch his face crumple up and his mouth turn down and his legs stop wagging while he prepared to let out a heartbreaking scream. Immediately I would begin to feel terrible, and would pick him up in my arms and try to comfort him, out of fear that I’d been spotted and because I suddenly felt sorry for him. And I’d lug him into the kitchen saying, “Oh, Missiz Robinson, Luke is crying about something and I’m trying to make him feel better.” She would scoop him up and bustle off, not particularly concerned about his racket because Luke was the eighth child and she was used to noise. She would certainly never bother snooping around to find the pinch mark on his arm.

Everyone in the boardinghouse gathered for dinner on Sundays. Mother and Tia would prepare roast beef, popovers, mashed potatoes, and vegetables grown in our own garden. My sister Pauline and I would set the table or do the dishes, jobs which we alternated with Tia’s children: fifteen-year-old, boy-crazy Mary, who had a photographic memory and an unchartable I.Q. and could play classical music by ear on the piano; and her son, Skipper, at thirteen badly in need of a father’s strong hand, who lit fires in his basement bedroom, smoked, was flunking out of school, and generally raised hell with his delinquent friends. He was my favorite cousin. After we’d all held hands and sung “Thank You for the World So Sweet” my father would put Bach or Brahms or Beethoven on the phonograph and my mother would carve the roast, and while the boarders would try to carry on a conversation, Pauline and I would pinch and swat each other under the table. Mimi, who had learned to dance almost before she learned to walk, would pirouette around the floor with her toes curled under, changing the records on the phono—her latest trick, which everyone except Pauline and me thought was terribly cute. With her black hair and blue eyes, Mimi, “the littlest one,” was beautiful. Pauline and I were united against her.

In one of my mother’s albums there’s a photograph of me sitting all alone at the big oak table with its extra leaves and knife scars rubbed smooth and shiny. I am wearing my navy blue corduroy dress with the gold buttons and the white eyelet smock tied over it, and I’m staring through the heavy tiresome minutes that follow an afternoon nap. I remember the stony feeling, as though weights hung from my shoulders and my eyelids were made of clay. I longed to be awake and lively, dashing and playing. But whatever demons would haunt me for the rest of my life were busy at work even then.

The scrape of a new school lunch pail filled me with terror. Because overalls were not allowed in the new school, I wore sweaters tied in giant knots around my waist. I had attacks of nausea, and one teacher or another would hold my head while I hung over the toilet, but nothing was ever forthcoming—from the age of five, I had developed a fear of vomiting that remains with me (to a much lesser extent) today. What cataclysmic event shook my sunny world so that it was shadowed with unmentionable and unfathomable fright? I don’t know. I never will know. Every year, with the first golden chill of fall or the first sudden darkness at suppertime, I am stricken with a deadly melancholy, a sense of hopelessness and doom. I become weighed down, paralyzed, and frozen; the hairs on my arms and legs rise up and my bones chill to the marrow. Nothing can warm me. In the eye of this icy turbulence I see, with diamond clarity, that small shining person in the photograph, with slept-on braids and a groggy pout, and a ribbon of worry troubling her black eyes as she sits down with all her small might on the memories of a recurring dream: I am in the house and something comes in the night and its presence is deathly . . . I scream and run away, but it comes back at my nap time and gets into my bed. Then a voice says angrily, “Don’t look at me!” as I peer at the face on the pillow next to me, and I feel very ashamed.

That’s all I have ever remembered—just that much and no more.

The boardinghouse lasted a chaotic two years until my father finished his degree. At that time most of the bright young Stanford scientists went off to Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the atomic bomb was being developed. My father recognized the potential destructive power of the unleashed atom even in those early days. So he took a job as a research physicist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. We settled into a two-story house on a street lined with maple trees, in a tiny town of eight hundred called Clarence Center, an hour’s drive from Buffalo. Suddenly life was calm. Pauline and I took piano lessons. While Mother cooked supper she would hum and I would sit and listen to the evening serials “Sergeant Preston of the Yukon” and “Jack Armstrong” on the big kitchen radio. The new school was small: I didn’t leave class and run home; I stayed and got straight A’s. I also acquired my first best friend, a girl named Lily who lived on a real farm, where I discovered piglets and slept overnight in the hayloft.

Soon my father was invited to become head of Operations Research at Cornell. Exactly what the job entailed was classified information, but he was offered a three-week cruise on an aircraft carrier as an introduction to the project and promised a huge salary. As it turned out, he would be overseeing Operation Portrex, a vast amphibious exercise which among other things involved testing fighter jets, then a relatively new phenomenon. Millions of dollars would be poured into the project, about which he was to know little and say less. Mother showed us the letter he wrote from “sea” with little hand-drawn cartoons of his feet tilting back and forth in his bunk during a week-long storm. He had been very, very seasick.

By now my father had begun to ask himself whether, with the overwhelming capacity of the A-bomb to wreak total ruin, there was any such thing as “defense.” As he struggled with the question—and with the lucrative offers that would assure him and his family comforts thus far unknown to us, my mother suggested we change churches. Though she personally did not like organized religion, for my father’s sake we had joined the Presbyterian church out west. I, for one, had enjoyed dressing up, polishing my patent leather shoes with Vaseline, and sitting next to my mother during the service, smelling her perfume and face powder. When the congregation stood up to sing, her voice rose up more sharply and prettily than all the others, at least to my ears, and I loved the cozy sound of purses clicking open, of the little paper envelopes slipping into the collection plate, and the rustling of the ushers. But now my mother shepherded us, innocents, to the Quaker meetinghouse in Buffalo, hoping to help my father find some spiritual guidance and direction.

Quaker Meeting—what a horror! A room full of drab grown-ups who sat like ramrods with their eyes closed, or gazed blissfully at the ceiling. No one dressed up and there was an overabundance of old people. The few other children were no consolation because we didn’t like them. Their parents were “permissive,” a term we came to understand by way of a horrible little redheaded boy who slithered off his chair and crawled the entire length of the floor every Sunday. One day he caught Pauline scowling at him, and he bit her leg and scuttled off, leaving her clutching her wound and fighting back tears. His mother chose that meeting to rise and speak on the godliness of children, while Pauline and I tried to scorch her flesh with our eyes.

It seems extraordinary that we sat in that room for only twenty minutes each Sunday, so vivid is my memory of the weight of time upon our young souls, the depressing tedium of silence broken only by tummy-rumbling, throat-clearing, and an occasional message from someone whom “the spirit” had moved to speak. The grownups stayed there, by choice, for a full hour, but after twenty minutes we would be herded out to First Day School (Quaker Sunday school) and left in the charge of a dear old white-haired lady whom we were determined to dislike, though she had only goodness in her soul and love for us, and a determination to teach us the wonders of the Lord. One Sunday she announced to her squad of five- to ten-year olds, “Today we are going to witness a miracle.” Pauline and I looked at each other and then heavenward.

“A meer-a-cul. P.U.,” I said. “How stupid,” said Pauline.

The old lady was poking around in a big cardboard box, mixing fertilizer with rich dark earth. Her wrinkled hands lovingly crumbled the earthen chunks with such care and pleasure and efficiency that I salivate now as I see it. She had us fill tin cans with earth and then, from her garden apron pocket, she produced a palmful of whitish green-bean seedlings. Each of us planted one, watered it, stuck it on the windowsill and promptly forgot about it.

Returning the following Sunday, we peered into our tin cans and saw the shiny bump of a spear poking its way out of the earth. The old lady looked delighted, standing in the winter sunshine pouring in from the window, her face, fringed by the tufts of her white hair escaping the bun in back, radiating a childlike joy. “This wondrous sprout growing up from its shell is seeking the sunlight,” she explained. “And that is what we all must do daily with our lives.”

I must say we were not impressed with the miracle. Certainly the lesson was lost on me then, and I quit attending Meetings when I was eighteen, as soon as I left home. I did not return for more than two decades, until, in my forties, I encountered one of those tedious mid-life crises. One morning, just before waking from a long and mystifying dream, I clearly saw that dear old white-haired lady from the Buffalo Quaker Meeting, still standing in the sunlight and smiling down upon a two-inch-high bean sprout. I wanted to apologize for having been such a brat, but she dissolved into a mist and I woke up in tears. I decided to go back to Meeting, which I have been attending irregularly ever since, rather belatedly coming to appreciate the miracle of the bean.

As for my father, whose struggles of conscience had drawn us to Quaker Meetings in the first place, in that austere silence he became a pacifist. Rather than get rich in defense work, he would become a professor. We would never have all the fine and useless things little girls want when they are growing up. Instead we would have a father with a clear conscience. Decency would be his legacy to us.

Shortly after Mr. Everette, our cross-eyed piano teacher, had assisted me in conquering the three-note “Ann, Ann, Sister Ann,” and had explained all about sharps and flats, I went home and took a book from the piano bench and, making sure I was alone, placed it on our little upright. I searched the pages for the shortest song, with the least number of sharps and flats, and taught myself, note by note, Beethoven’s Sonata in G (opus 42). The glorious calm that resulted inside me lasted for our whole stay in Clarence Center.

Soon we were on the move again. My fifth grade was spent in southern California, where Popsy (as we called my father) taught physics at the University of Redlands. In my dreams, our tiny onestory white house in Redlands is the one I return to most often. It had a front lawn lined on one side with huge, many-colored roses which my mother tended. Another house much like it stood on our right side, and an empty lot full of stickers lay like a desert on the left, bordered by Mrs. Fisher’s row of pomegranate trees, behind which she lived a dank existence with her aging spaniel, Sunny. Ivy grew all around our front porch. My father had paid eleven thousand dollars for the house. I felt that my mother and father had the most sophisticated taste of anyone on the block. I’m sure they did. In fifth grade the three outstanding people in my life were my collie dog, Woolie, Mr. Macintosh, my wonderful teacher, and Judy Jones, a girlfriend.

After one year Popsy took a job with UNESCO, to teach and build a physics lab at the University of Baghdad. Perhaps that was where my passion for social justice was born. The day we landed, in the heat and the strange new smells, we were horrified to see an old beggar being driven out of the airport gates by policemen using sticks and shouting in a crude and guttural language. In Baghdad, I saw animals beaten to death, people rooting for food in our family garbage pails, and legless children dragging themselves along the streets on cardboard, covered with flies feasting on open sores, begging for money.

We all got sick with “Baghdad tummy.” Pauline and Mimi recovered, but had already passed on to me a case of infectious hepatitis they’d just gotten over. Mother says that the first time she took me to the hospital, I staggered over and gave my two sugar candies to an Arab woman who was wrapped in her filthy black chador, hunched on the tile floor, moaning in pain. I wanted everyone to feel better. It would be a long time before I felt better.

I was in bed for months, and for all that time my mother was always near, her strong hands tilting my head up for rice water and glucose powder, and later, mashed black bananas. The life line in my right hand split and disappeared. Even when I stretched the skin across it, hard, it wouldn’t come back. I thought I would surely die in that strange land, where the sweet smell of oranges filtered through the thick odor of diesel exhaust. But as I slowly regained my strength, the illness became a wonderful excuse to spend a year at home drawing, knitting, cooking, playing with ants, collecting bugs, and, when I was better, rescuing dogs.

Pauline and Mimi, by contrast, had a miserable time of it at the Catholic convent school. Mimi swears she never recuperated after Sister Rose displayed her math paper to the class as an example of poor work, then wadded it up and threw it at her, over the ducking heads of the diplomats’ sons and daughters who constituted the Englishspeaking classroom. Pauline, more fortunate, discovered that she was an able seamstress and spent her school year buying cloth with Mother at the open bazaars and making her own wardrobe.

All in all, Baghdad was a melancholy place. The sky turned red at sunset, the birds flying in zigzagging clouds, singing in a thousand voices. Despite my illness I began to feel a part of Baghdad, as though its sufferings were also mine. I certainly felt closer to the beggars in the streets than I did to the people who sat around the British country club talking about punting on the Cam and how difficult it was to get these bloody natives to do anything. I felt sorry for the bloody natives.

More than twenty years later, in 1974, I returned to the Middle East on a concert tour. On a stopover in Lebanon, I met an Arab woman in designer sunglasses out by the hotel pool. “I read your book Daybreak,” she said to me. “Why you deen’t say something nice about Bach-dad? It is a beautiful ceety.”

I should have told her that, driving across Tunisia, I had been flooded with memories of Baghdad. How when the winter was over, we kids moved our beds out to the roof, and through the mustysmelling mosquito net I spoke to the stars, telling the Big Dipper things I could never tell any person. How I sat in the sun and ate Haifa oranges and browned my skin, dreaming that the King of Iraq, at the time only a prince of twelve, would pick me out of the crowd of onlookers as he pranced down Al Rashid Street on a white horse, and tell me how beautiful I was. (I had learned enough Arabic to carry on an imaginary dialogue with him which would lead to my being a chosen visitor at the palace, and eventually an Arabian princess.) And how during the dust storms which would enshroud us in a fierce brown wind for days at a time I inhaled the desert into my lungs and absorbed it into every pore of my body, and understood the hardships of my brothers and sisters who inhabited that arid land.

It was not till Tunisia that I understood the magic and sorrow of the Middle East—in an ocean village where magenta blossoms drooped over white walls and I danced through the streets in a purple dress bought for fifty cents in an open store front. I rode a small Arab horse beside the sea and learned the popular song “Jaria Hamouda” from the five daughters of an innkeeper, all perched like fat crows on the same note as they sang into my tape recorder.

At the end of our year in Baghdad—1951—we returned to Redlands, California, where I faced junior high school with the same enthusiasm with which I’d faced all new schools. I averaged about three days a week in class, and the rest at home with the excuse that I was still feeling sick. Mother began a round-robin of taking me to clinics for testing, but there was in fact nothing physically wrong with me. My real problems were the fears that continued to plague and sometimes incapacitate me, now compounded by the rigors of adolescence.

One of the first problems I had to confront in junior high school was my ethnic background. Redlands is in southern California and had a large Mexican population, consisting mainly of immigrants and illegal aliens who came up from Mexico to pick fruit. At school, they banded together, speaking Spanish—the girls with mountains of black hair, frizzed from sleeping all night long on masses of pincurls, wearing gobs of violet lipstick, tight skirts and nylons, and blouses with the collars turned up in back. The boys were pachucos, tough guys, who slicked back their gorgeous hair with Three Roses Vaseline tonic and wore their pegged pants so low on the hip that walking without losing them had become an art. Few Mexicans were interested in school and they were ostracized by the whites. So there I was, with a Mexican name, skin, and hair: the Anglos couldn’t accept me because of all three, and the Mexicans couldn’t accept me because I didn’t speak Spanish.

My “race” wasn’t the only factor that kept me isolated. The 1950s were the heart of the Cold War, and if anyone at Redlands High School talked about anything other than football and the choice of pom-pom girls, it was about the Russians. I had heard that the Communists had rioted at the University of Baghdad when my father taught there, and that some of them always warned him to keep away when there was going to be trouble. But in America during the overheated McCarthy years, communism was a dirty word and the arms race a jingoistic crusade. In my ninth-grade class I was almost alone in my fear of and opposition to armaments (to me they made the world seem even more fragile) and was already considered an expert on anything political.

It wasn’t that I knew so much but rather that I was involved, largely because of the discussions taking place in my own home. And the family attended Quaker work camps where I heard about alternatives to violence on personal, political, national, and international levels. Many of my fellow classmates held me in great disdain, and some had been warned by their frightened parents not to talk to me.

I don’t know how Pauline felt about politics in those days. She was an excellent student but suffered terribly from shyness. I idolized her because she got good grades, never carried a wrinkled lunch bag, wore a ponytail which didn’t make her ears stick out, and smelled of violets. Also because she was white. She never said a word about social issues. And Mimi—well, my own pacifism did not yet extend to Mimi, who was avoiding me in public because I was brown.

It was the sense of isolation, of being “different,” that initially led me to develop my voice. I was in the school choir and sang alto, second soprano, soprano, and even tenor, depending on what was most needed. Mine was a plain, little girl’s voice, sweet and true, but stringy as cheap cotton thread, and as thin and straight as the blue line on a piece of binder paper. There was a pair of twins in my class who had vibratos in their voices and sang in every talent show, standing side by side, each with an arm around the other, angora sweaters outlining their developing bosoms, crinoline slips flaring. They swayed to and fro and snapped their fingers, “Oh, we ain’t got a barrel of money . . .” I heard a teacher comment that their voices were very “mature.” I tried out for the girls’ glee club, and when I wasn’t accepted, figured it was because (1) I was not a member of the in crowd and (2) I had no vibrato so my voice wasn’t mature. Powerless to change my social standing, I decided to change my voice. I dropped tightrope walking to work full time on a vibrato.

First I tried, while standing in the shower, to stay on one note and force my voice up and down slowly. It was tedious and unrewarding work. My natural voice came out straight as an arrow. Then, I tried bobbling my finger up and down on my Adam’s apple, and, to my delight, found I could create the sound I wanted. For a few brief seconds, I would imitate the sound without using my hand, achieving a few “mature”-sounding notes. This was terrific! This is how I would train!

The time it took to form a shaky but honest vibrato was surprisingly short. By the end of the summer I was a singer.

At the same time I was giving myself a new voice, I was also under the tutelage of my father’s much-loved physics professor, Paul Kirkpatric, P.K. for short, conquering the ukulele. I knew the four basic chords used in ninety percent of the country and western and rhythm and blues songs then dominating the record market, and I was learning a few extra chords to use if I needed to sing in a key other than G. Some of my favorites were “You’re in the Jailhouse Now,” “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” “Earth Angel,” “Pledging My Love,” “Never Let Me Go,” and the “Annie” series—“Annie Had a Baby,” “Work With Me Annie,” “Annie’s Aunt Fanny” (I was disgusted with the watered-down “white version,” “Roll With Me Henry”)—as well as “Over the Mountain,” and “Young Blood.” These songs all could be played with five chords, most with only four. All were either melodic and sweet, upbeat and slightly dirty, or comic. I even did a vile racist version of “Yes Sir, That’s My Baby” called “Yes Sir, Zat-a My Baby,” and Liberace’s inane “Cement Mixer, Putty Putty.” And this list is only a bare beginning of what I listened to on my little grey plastic bedside radio. I cannot describe the satisfaction I got from memorizing tunes by ear and scribbling down words anytime day or night, finding the right key (the choices were C or G) and making the song my own.

At school, I had gained a reputation as a talented “artist.” I could sketch cartoons as well as likenesses of movie stars, Bambi and the other Disney characters, and any student who was willing to sit still for ten minutes. I also painted campaign posters, once even for two of my classmates who were running against each other.

I did have a few friends. Bunny Cabral was a Mexican girl who wouldn’t speak Spanish, and we ended up pretending to be sisters. She had four brothers and a television set, and I loved to stay at her house. We’d listen to the rhythm and blues station late into the night, and I’d break into a sweat when her oldest brother, Joe, came home. He never noticed me, but another brother, Alex, did, and later was the first person I ever dated. He gave me a record of The Flowering Peach for Christmas when I was fourteen. And there was Judy Jones, who continually risked her status as a “popular” kid to befriend me. She was like my sister Pauline: beautiful, with her hair curled and pulled back in a flawless ponytail, eyebrows plucked, the colors of her sweater, collar, and scarf perfectly coordinated, her skirt even at her ankles, her saddle shoes fastidiously polished. Her lunch bag was new, and her books and binder were in impeccable order. She wore “natural” lipstick. By contrast, I was Joanie Boney, an awkward stringbean, fifteen pounds underweight, my hair a bunch of black straw whacked off just below my ears, the hated cowlick on my hairline forcing a lock of bangs straight up over my right eye, my collar cockeyed, my scarf unmatched and wrinkled, my blouse too big, my socks belled, my shoes scuffed, my lunch bag many times used and crumpled, lines under my eyes, and no lipstick. My best feature was what my parents referred to as my “million-dollar smile.”

The rest of my world was just as disordered as my person. I kept the bedroom which I shared with Mimi looking like a cross between a garbage dump and a remnants sale. It was strewn with T-shirts, dirty socks and gym clothes; old lunch bags filled with peanut butter sandwich crusts, banana peels, and dried-up orange sections; crinoline slips and wrinkled nylon scarves; my collections of porcelain animals and bones; and my drawing equipment—pencils from B to H, pens of every existing quill size, bottles of india ink, chalk pastels, charcoal, oil and watercolor paints and brushes. Examples of my artwork were pinned and pasted from one end of the room to the other. My textbooks languished unused amid the clutter on my unused desk. In this chaotic section of my family’s tidy house, I would pick up my ukulele, flop onto my lower bunk of our bunk bed, hook my toes around the springs of the upper bunk, and play my four chords and practice my new voice. One song I distinctly remember singing from that heap of rubble (one of the first non-r&b songs I learned) went:

When you climb the highest mountain

When you think you can’t find a friend

Suddenly there’s a valley

Where the earth knows peace with men

And life and love begin.

It is not a coincidence that this popular song was a favorite of mine when I was fourteen, or that I remember it so clearly now. In the chaos of my teenage life it held out hope for the end of my mystifying problems, and also for the end of the troubles of the earth.

Before long an exhibitionist impulse overcame me. I took my ukulele to school. At noontime I hung around the area where the popular kids ate lunch and waited for them to ask me to play, which they did soon enough. I sang “Suddenly There’s a Valley” and when they applauded and asked for more, I sang the current hits of the day: “Earth Angel,” “Pledging My Love,” and “Honey Love.” I was a big hit, and came back the next day for a command performance. This time I did imitations of Elvis Presley, Delia Reese, Eartha Kitt, and Johnny Ace. Before the week was out I had gone from being a gawky, self-conscious outsider to being something of a jesterlike star.

Someone suggested that I try out for the school talent show. At the tryouts, while standing at the microphone, I rested my foot on the rung of a stool to feign calm, and discovered that my knee was shaking. Afraid I would rattle the stool, with seeming nonchalance I raised my foot off the rung and held my knee suspended in the air, foot dangling, my entire leg trembling. The rest of my body was impressively composed, and I sang “Earth Angel” all the way from start to finish with a “mature” vibrato. Nobody noticed my shaky knee, and I discovered that I had an innate poise and a talent for bluffing. Clearly I would “make” the talent show. I hoped to win the prize.

For my first stage performance I wore my favorite black jumper, polished my white flats, and even dabbed on some lipstick. I was terrified, but was told later that I had been “cool as a cucumber.” As the crowd clapped and cheered I grew so nervous and thrilled I thought I would faint. They wanted me back for an encore, so, knees watery, I went back out and sang “Honey Love.”

There had been nothing showy about my performance. I had walked out and sung exactly the way I would in my room or on the back porch. The actual time in front of an audience was both frightening and exhilarating, and afterwards I was euphoric.

I did not win the prize. It went to David Bullard, the only black in the show. The judges had picked the only horse darker than me. David had befriended and defended me in the fifth grade and I loved him. He was tall and smoky black, had perfect teeth, and may have been the only person in that school who smiled as readily as I did. He also had a good voice. The fact that I didn’t win the prize I’d been expecting dampened that day only a little. For all the anxiety, I knew I’d been really good and that, in some strange way, my peers loved me and were proudly claiming me as one of their own, as someone who truly belonged to Redlands High School. My sense of having arrived was almost as heady as my satisfaction with the performance.

I started “going out” with a very attractive senior named Johnnie Dahlberg, a Mexican who used his stepfather’s Swedish name. He was cute and drove a Mercury. I would lie in bed at night and conjure up Johnnie’s face as it looked in the reflection of the flickering movie lights, and I would dream of kissing. I had lain in his imaginary arms for so many sweaty hours that I was almost sick of his face when I saw him on campus Monday mornings. Then, on the third date, Johnnie tried to kiss me good-night, Hollywood style, and in spite of all the romance magazines I’d seen at Bunny’s, I was caught unawares. After I’d run, traumatized, into the house and stared in the mirror for twenty minutes to see if I was still my parents’ little Joanie, I wrote him a three-page letter about how wicked he’d been, and then spent the next three months wishing he’d try again.

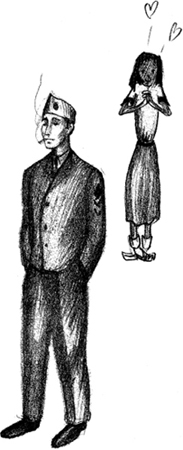

I would have only one more year to enjoy my new stature at Redlands, for the following summer we’d be moving back to Stanford University, where my father had accepted a teaching job. During that final year I wrote and illustrated an essay, which I rediscovered thirty years later when preparing to write this book. I’m reproducing part of it here with some of the original drawings because it so perfectly reflects the youthful self I remember—though of course its wistful earnestness and painful bravado are somewhat embarrassing to me now. But I’m struck by its prescience—not only how well it anticipates some of my life’s events but also how consistent some of its sentiments are with my beliefs today.

What I Believe (1955)

ME

I am not a saint. I am a noise. I spend a good deal of my time making wise cracks, singing, dancing, acting, and in the long run, making a nuisance of myself. I love to be the center of attention, and pardon the conceit, I usually am. I like to show off, and if you know me at all, I needn’t elaborate on the subject.

Showing off, in a far distant way, coincides with my philosophy. Because for every five or six people who get disgusted and sore at me for getting so much attention, there is at least one who is getting some fun out of it. I am making somebody get a little joy out of life.

I am a very moody person. For although I am all the things that I have mentioned so far, I also do a little thinking once in a while. I sit sometimes and just think; about whether I’m turning out to be what my parents want, or whether I’m letting them down, about life, death, and religion, then I wind up thinking about boys and that’s what really makes me moody.

Another point in me is that I am friendly. I always like to stick up for the underdog. I don’t like to snub anybody. Why should I? “There is that of God in every man.” Even the cheapest of us. It’s annoying to society when I am talking with them and I stop in the middle of a sentence to say high to some degenerate looking dilinquent with an I.Q. zero. I prefer middle and low class people to snob hill when it comes to friends.

Many things interest me. (This is not according to some personality test I took in ninth grade. That told me I had no interests and great withdrawel tendencies.)

I love to draw. I am taking a correspondence art course and maybe someday I’ll end up doing it professionally. Mother said I have been drawing since I was too young to rember. She said we always had the beds, bureaus, and walls repainted frequently. She got tired of seeing roosters, Indian tee-pees and cows with big udders crayoned all over the house.

As you see, my art often runs along the gruesome lines. I get inspired by various people to create these lovely ditties.

With art I guess I can help fulfill my philosophy by creating for others.

I like to act as well as to draw. In acting I can make a lot of people enjoy themselves at one time (or visa-versa). I like to play all sorts of rolls; negro maids, fairy queens, and even the mother of John the Baptist.

Please don’t think that I do all this for the sake of others only. I live on glory.

I enjoy singing also. I sing most of the time, performance or otherwise. My geometry teacher doesn’t appreciate it much when he is trying to explain how to bisect a quadrilateral and I start singing “You’re All Wrong”.

I find that singing is a good outlet. When I get depressed I sing songs to prove to me that life isn’t really so bad and when I am bursting with goodwill I pick up a guitar and bellow it out of me. I sing for the family and for company alot, but I have found it wiser not to sing for my contemporaries anymore.

I have been told by an authority on the subject that I don’t know how to dance. But for some reason, I was bop queen in 9th grade. I do not pretend to know how to dance because I don’t. I have found, however, that if you look and act enough as if you know what your doing, it deceives about 99/00% of the people watching.

I love to dance (even if I can’t) and I have fooled enough people into thinking I can that I am considered quite superior on the subject of bopping.

MY MALE

I always worry about what my male will be like, because I want him to be as wonderful as my father, but I don’t think it’s possible.

Popsy is hard working, good looking, fun-loving, faithful, and he likes music. Besides he’s smart. If I expect all that I will end up an old maid. (Maybe I oudda just settle for good looks.)

I want to be a good wife someday, but not for awhile yet. I am going to do the rounds first, and then pick one out and settie down peacefully for the rest of my life. Sounds nice, doesn’t it? Well it won’t work out that way. Because I won’t want to “settle down peacefully.” I will want to travel and he will probably be a pauper anyway so, you see, it won’t work out.

I don’t speak seriously on this subject because I think I am too young to really know what I want yet.

Right now I am at the stage where I am in love with the whole opposite sex. I get chills every time I see certain people and it’s been going on like this since I was ten.

I can say this though. I do want my man to be faithful and hard-working, and I shall try to please him as best I can.

Our family is all race prejudice. We are always on the side of the black, brown, yellow, or red. Whenever there is an argument going on between a negro and an anglo, I immediately take the side of the negro. It isn’t a good habit, I suppose, but it is better than the other way around.

I think one of the saddest and stupidest things in our world is the segregation and discrimination of different races. A man is what he makes himself and fortunately the “minority” races are getting more and more of a chance to prove their worth. The negro, for instance, has proved his talents in singing, dancing, and most of all, sports. Robinson, Louis, and, at one time, Robeson, show what the race is capable of doing.

I have run into a few problems myself because of the fact that I am 1/2 mexican. I turn pretty dark in the summer.

Once when we moved to a very small, narrow-minded town in New York, somebody yelled out of a window at me, “Hey! Watcha doin, nigger?” I wasn’t the least bit hurt, my reply was, “Wait till you see me this summer when I get my tan!”

That concludes my little section on race.

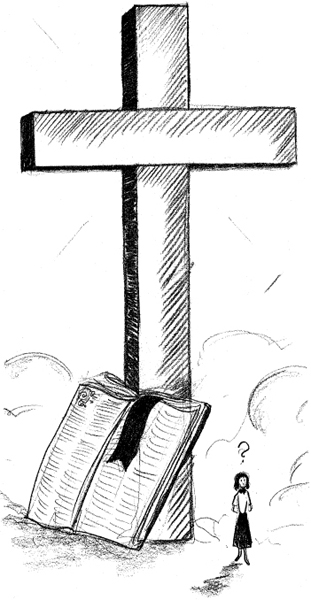

ME AND RELIGION

I am now entering my most touchy subject.

I don’t know what to believe. I would like to be able to believe everything straight out of the Bible, fact for fact, in the manner of a devout catholic. But common sense, or perhaps disbelief tells me no.

My parents are Quakers. I like the idea the Quakers have of silent meditation, but I hate the meeting here in town. Perhaps if I had not been brought up by Quakers, who do not believe in taking what the Bible says literally, I might believe.

I do believe this. There is a supreme power that makes us do the good we do, that makes our concience tick. Some supreme power supplies all the everyday miricles that take place.

Scientists can prove facts about the beginning of man and animals that seem to contradict the Bible stories. But these proofs can go back just so far. They go back to say that the earth was once a big round blob floating around in nothingness. But no one can ever prove how that blob got put there. Some power got it started. That same power, I think, is the power that rules men’s spirits today. That, I think, is God.

Sometimes I see God as an old man with a great white beard and a flowing robe. I love this old man and he loves me. Right now he is sad about the condition his little world is in now. He shakes his head and wrinkles his brow when he sees the mushroom cloud of the A Bomb blast. I think this God is going to leave everything up to us. He is going to see what we do to ourselves. He will not warn us before we make a fatal move, but he will be sad and disappointed when he sees our world destructed by wars.

I want to do things to make this old man pleased. I don’t want to be selfish. When I think of God, I think of the earth as a very small thing. Then I think of myself as hardly a speck. Then I see there is no use for this tiny dot to spend its small life doing things for itself. It might as well spend its tiny amount of time making the less fortunate specks in the world enjoy themselves.

That is what I believe.

I began the eleventh grade at Palo Alto High School, which did not have a Mexican problem because all the Mexicans lived in nearby San Jose. Aside from the expected bouts of nausea and anxiety that were simply part of my life, I fit in surprisingly well. I was finding friends through a more unlikely source, too—the Quakers, or more specifically, their social action wing, the American Friends Service Committee. That year, along with three hundred other students, I attended a three-day conference on world issues held at Asilomar, a beautiful spot on the pine-speckled, foggy beaches of Monterey. Not only did I fall in love with ten or twelve boys at once, but I was galvanized by the discussions, inspired in a way I had never been before. I found that I spoke forcefully in groups both large and small, and was regarded as a leader.

There was great excitement about our main speaker, a twenty-seven-year-old black preacher from Alabama named Martin Luther King, Jr. He was a brilliant orator. Everyone in the room was mesmerized. He talked about injustice and suffering, and about fighting with the weapons of love, saying that when someone does evil to us, we can hate the evil deed but not the doer of the deed, who-is to be pitied. He talked specifically about boycotting busses and walking to freedom in the South, and about organizing a nonviolent revolution. When he finished his speech, I was on my feet, cheering and crying: King was giving a shape and a name to my passionate but ill-articulated beliefs. Perhaps it was the fact of an actual movement taking place, as opposed to the scantily attended demonstrations I had known to date, which gave me the exhilarating sense of “going somewhere” with my pacifism.

It was also through the Quakers that I met Ira Sandperl the following year. One sunny day at Meeting, in place of the usual sinking Sunday boredom, there was a conversation with a funny, brilliant, cantankerous, bearded, shaven-headed Jewish man in his early forties with immense, and immensely expressive, eyes. I couldn’t know when I first met him that he would end up being my political/spiritual mentor for the next few decades.

Ira read to the teenage First Day School from Tolstoy, the Bhagavad-Gita, Lao-tse, Aldous Huxley, the Bible and other texts we had never discussed in high school. For the first time in my life I looked forward to going to Meeting. Ira was a Mahatma Gandhi scholar, an advocate of radical nonviolent change. Like Gandhi, he felt that the most important tool of the twentieth century was organized nonviolence. Gandhi had taken the concept of Western pacifism, which is basically personal, and extended it into a political force, insisting that we stand up to conflict and fight against evil, but do so with the weapons of nonviolence. I had heard the Quakers argue that the ends did not justify the means. Now I was hearing that the means would determine the ends. It made sense to me, huge and ultimate sense.

Ira adhered to nonviolence with a kind of ferocity which would eventually come to me as well. People would accuse us of being naive and impractical, and I was soon telling them that it was they who were naive and impractical to think that the human race could continue on forever with a buildup of armies, nation states, and nuclear weapons. My foundations in nonviolence were both moral and pragmatic.

One day it was announced at school that we were to have an airraid drill: three bells would ring in sharp succession, and we would all get up quietly from our seats and calmly find our ways home. We could call our parents, or hitch rides, or whatever we pleased, but the point was to get home and sit in our cellars and pretend we were surviving an atomic blast. The idea, of course, was as ludicrous then as it is now—despite the fact that in the atomic fever of the 1950s even some fairly sensible people were stocking their cellars with drums of water, saltines, and Tang.

I went home and hunted through my father’s physics books to confirm what I already knew—that the time it took a missile to get from Moscow to Paly High was not enough time to call our parents or walk home. I decided to stay in school as a protest against misleading propaganda.

I was in French class when the three bells rang, and with pounding heart, I remained seated and reading. The teacher, a kindly foreign exchange teacher from Italy, waved me toward the door.

“I’m not going,” I said.

“Now what ees eet.”

“I’m protesting this stupid air raid drill because it is false and misleading. I’m staying here, in my seat.”

“I don’t theek I understand,” he said.

“That’s OK. Neither will anybody else.”

“Comme vous êtes un enfant terrible!” he mumbled as he left the room, shaking his head and tucking his multitude of disorganized notes higher under one arm.

The next day I was on the front page of the local paper, photograph and all, and for many days thereafter letters to the editor streamed in, some warning that Palo Alto had communist infiltrators in its school system.

Having opposed it before, my father now seemed pleased with my bold public action: I may have proven to him that I was serious about something aside from boys. My mother thought it was wonderful.

The action delighted Ira and cemented our relationship, to the great unhappiness of his wife. We’d walk for hours around the Stanford campus, talking and laughing until we were in tears at the folly of humankind, then we’d plan future actions to organize a nonviolent revolution and create a better world. I was enormously happy. My father was nervous about Ira and thought I should be paying more attention to school and studies.

“Doesn’t this man have a wife?” he asked Mom. But Ira and I have such a unique and special relationship that neither of us has ever adequately defined it: a platonic, deeply spiritual relationship, bound by the commitment to nonviolence and tempered with loud and frequent laughter and a healthy cynicism about the state of the world.

Ira and politics didn’t diminish the excitement I found in music. For fifty dollars of my own money I had acquired an old Gibson guitar. I don’t know now how I ever got my fingers wrapped far enough around the neck to press down on the strings. When I stood up the belly of the guitar reached almost to my knees, and I had to hunch over to get a grip. (Not knowing much about guitars I never thought to shorten the shoulder strap.) There’s an old photo of me singing at a college prom, dressed in a white evening gown with black straps that Pauline had sewn for herself the year before, topped with a silver lamé bolero my mother made especially for me. I have bare feet. My hair is in a pageboy, cowlick poking up gaily, sabotaging my attempts to look sultry. My mouth is a gob of lipstick and my eyebrow pencil is carefully sculpted for the Liz Taylor look. The guitar is hanging down on one hip, which is appropriately cocked to balance it. I look sort of funny and sort of sweet. On the one hand I thought I was pretty hot stuff, but on the other, I was still terribly self-conscious about my extremely flat chest and dark skin.

I was offered my first out-of-town job by a teacher from Paradise High School who’d heard me sing at the Asilomar conference. Although I wasn’t paid, my air fare was taken care of, and bumping through the clouds toward Paradise on a small aircraft (somewhere near Sacramento, California) I felt both very proud and very afraid. I was truly fawned over on this trip. Senior girls battled over whose house I should stay in and teachers wanted me to visit their classes. The father of one of the girls was a Shriner who dragged me off to sing at a dance hosted by members of his club. After three songs I sat down to have a Shirley Temple and a red-eyed old Shriner teetered over, put his arm around me and said in a kindly way, but with breath that could have withered a young oak, “You’ve got a helluva voice, kid. Don’t sign cheap.” I was far from thinking of signing anything, but I was blossoming in the attention.

I discovered the magnificent voice of Harry Belafonte. Tia told me about a man named Pete Seeger who was the daddy of folk music and I went to see him when he came to town, and soon after that heard the music of the queen of folk music, Odetta. I was slowly drifting from “Annie Had a Baby” and “Young Blood” to Belafonte’s “Scarlet Ribbons,” Pete Seeger’s “Ain’t Gonna Study War No More” and Odetta’s “Lowlands,” all of which I attacked with deadly seriousness.

My mother and father loved me to sing at gatherings of friends and students in our living room, and I was happy to oblige. I had no idea what Pauline thought of my new role, but Mimi liked it, and was herself soon to take up the guitar, which she would eventually play much better than I.

I was performing all the time. I sang at lunchtime and in the All Girls’ Talent Show. I sang at other high schools’ proms and in smoky dives for the parents of friends. And I was developing stage fright. Sometimes I was convinced that I had the flu—easy to believe with a headache, sore throat, nausea, stomach cramps, dizziness, and sweating fits. Once, at age sixteen, I had a terrible attack that turned my insides to water and had me crouching on the floor of the ladies’ room in a dance hall where I was scheduled to sing a couple of songs. A kindly woman felt my forehead and proclaimed a fever, called my parents, and sent me home. As soon as I was safely in the living room, in front of the fire with a cup of tea, all my symptoms vanished, and I stayed up and plunked and sang happily into the night. That, to my memory, is the only time I didn’t make it onto the stage.

Once I reached the stage, my voice usually functioned on cue, although occasionally the demons would strike during the concert: I would get short of breath, feel faint, or develop double vision; the words of the song would lose their meaning, or sound like a foreign language, and my terror would mount until I thought I would burst and evaporate into a dust cloud. By screaming silently to myself that I would be okay, I could usually overcome the sensations.

Still, singing helped me cope with the inevitable, overwhelming sexual tensions and excitement of adolescence. I flirted furiously from behind my guitar, sometimes staring into the eyes of one unsuspecting boy for an entire song. If he was tough, he’d look back the whole time. If he was with a girlfriend, the game was even more exhilarating. If the gaze really lasted, I’d feel myself go red and prickly from my toes to my scalp. There was no way to follow up on those forbidden stares, which was no doubt why I indulged in them so often. I flirted and sang, and developed a reputation for both.

By the time I reached my senior year, I had boyfriends: Sammy Leong, the only one my mother ever wanted me to marry (she wanted a Chinese Mexican grandchild); a football-playing bornagain Christian with whom I tore around on motorcycles, squinting against the wind to see the speedometer top 110 while he shouted scripture over his shoulder; a millionaire Stanford student who bought me dresses and watches, and who would frown and pout when he was ticketed for speeding in his Ferrari, wait until the policeman had walked back to his car, then peel out from the curb with a great “HAH!” and race furiously into the next county, grinding his teeth and cursing to the accompaniment of screaming sirens. Through Ira I met Vance, whose name I thought was wonderful and who was an “intellectual”; I soon threw him over for Richard, who sat up all night necking with me on some streetlit steps where the air smelled of orange blossoms and gardenias. I didn’t have friendships or affairs; I had escapades. I remained a virgin and kept myself in a psychic frenzy of unfulfilled crushes. My demons staged a powerful comeback, and finally, after a winter of seven colds and mounting attacks of nausea and despair, Mother packed me off to a psychiatrist.

I took a Rorschach test, identifying myriads of pelvises and skulls, and waited expectantly for the results so that I could be cured and feel better. To my great disappointment (I remember hot tears building up behind my downcast eyes), Dr. Heenen suggested that he did not have a crystal ball, and all the inkblot test could do was help find a starting place. I was with him only a short while before we moved, but I shall never forget that one day, when I was so frightened and anxious that I had curled up on the floor of his office, he reached out and took my hand, and I felt as if someone had saved me from drowning. I didn’t know then that my demons would never vanish, but I would have taken heart if I had known to what extent they could be placated, tricked, cajoled, and bargained with. The other day I gave a concert celebrating the twenty-seventh anniversary of my singing career. I looked out at a sparkling crowd of six thousand relaxed fans and marveled at how many years I had been walking out on stage. At that moment my stomach cramped up. I shook my head, laughed, and had a beer.