The Incas owed their extraordinary military successes in large part to their remarkably efficient social and administrative organization. However, as in other aspects of their culture, they were not so much revolutionaries as reorganizers and innovators. Thus, they adapted pre-existing social structures, norms, and traditions to fit their needs.

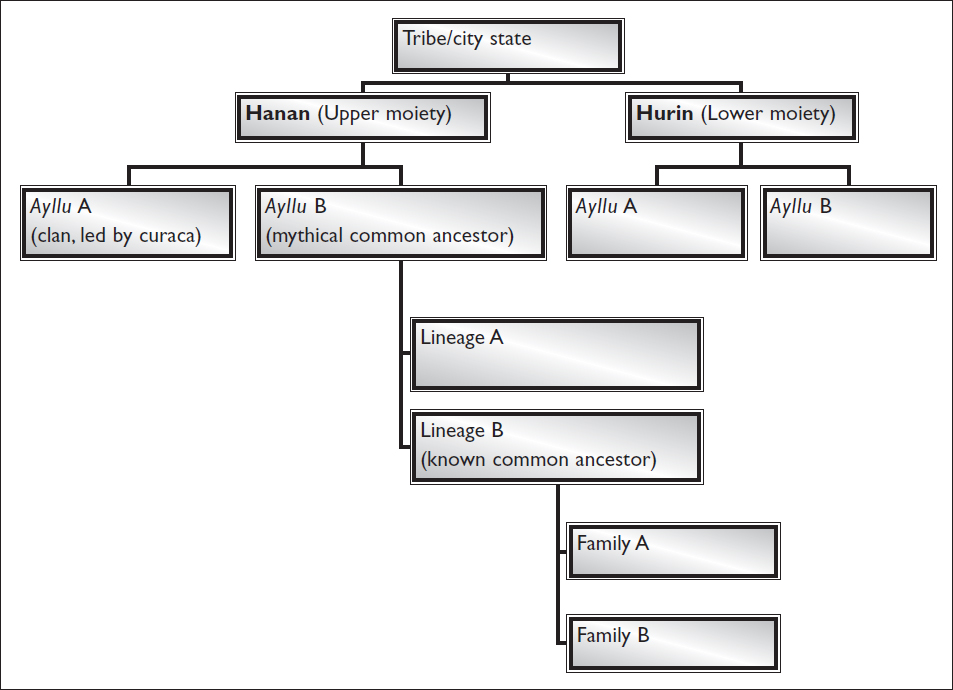

The basic kinship unit of the Andean Indians was the nuclear family, consisting of mother, father, and their offspring. These families formed closely related lineages that could trace their origin to a common known ancestor, which, in turn, formed ayllus or clans that traced their ancestry to one common mythical ancestor. These social units were bound closely together by ties of mutual reciprocity. A family could always count on its lineage for help at planting and harvest time as well as in cases of emergency. When it became time to work on more ambitious projects, such as the construction of irrigation ditches or planting terraces, the lineage could always count on the help of the other lineages of the ayllu. The help was always reciprocal, and if a man and his family lent a hand to his neighbor and kinsman, he could and did expect help in return. In exchange, he was expected to provide food, drink, and sometimes gifts, to all the helpers (Moseley, 1992).

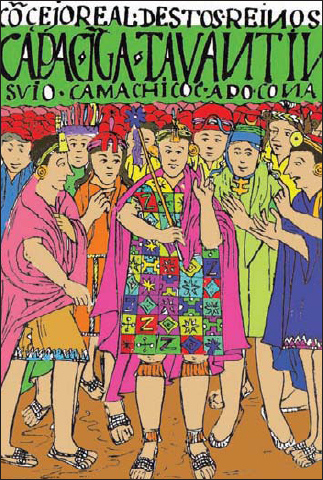

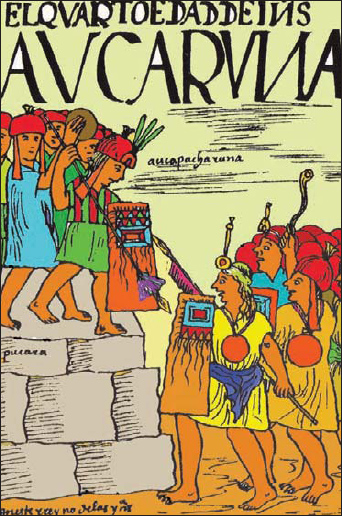

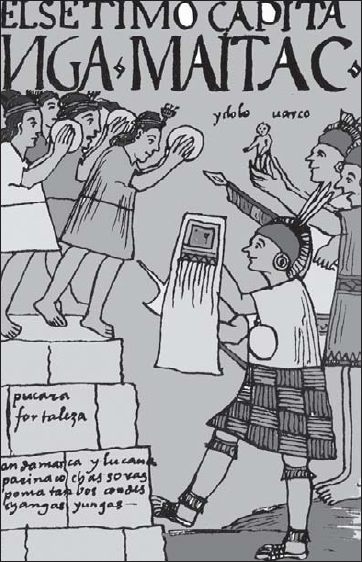

In this engraving, Guamán Poma de Ayala shows the Inca surrounded by his council consisting of his kinsmen and members of the royal panacas.

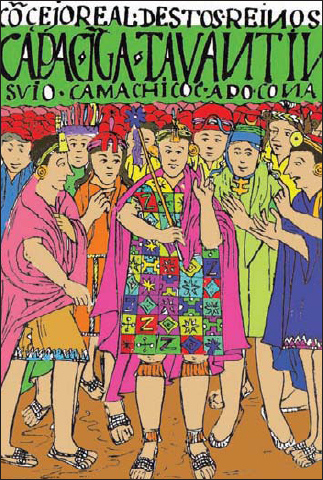

The colcacamayoc or “keeper of the storehouses” was responsible for collecting goods and services from his constituents and accounting to the Sapa Inca in Cuzco. Goods were stored in the local storehouse to be redistributed to the locals. Surplus goods were reserved for the Inca’s armies. When new supplies came in, the excess was sent to Cuzco.

The quipucamayoc or “keeper of the quipu” had a pivotal role in the administration of Tawantinsuyu. He was trained as a young boy in the code of the quipu, a set of knotted strings of various colors, lengths, and thicknesses. The early Spanish colonists reported that there were various types of quipu. Some quipus held the historical record of the Inca dynasty; others held population data, including the number of possible conscripts available in each district; others still recorded the agricultural production of each district, and similar information.

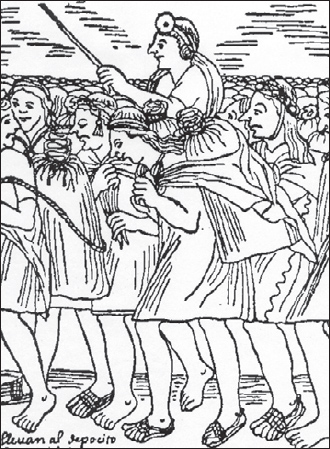

A cacique and his ayllu are on their way to deliver the mit’a to the Inca. The clansmen carry him on their shoulders to show respect. Higher-status individuals were carried on litters.

The leader of the ayllu, called curaca or cacique, did not hold a hereditary position, except, perhaps, in the city-states. He was chosen from among the more experienced and respected men of the various lineages. The more relatives a man had, the more likely he was to be selected, since he could commandeer the largest work force and be of most use to the community and/or the Inca. The curaca resolved disputes between lineages, allocated agricultural plots to the individual families of the ayllu, and helped plan and supervise major construction projects that benefited all the lineages under his leadership. Related ayllus formed larger units such as tribes, paramount chiefdoms led by capacs, or kingdoms led by sinchis. All the ayllus in the chiefdoms or kingdoms were generally grouped into two corporate entities called moieties: hanan (upper) and hurin (lower). Dual leadership reflecting the two moieties of the community was not uncommon.

After the Incas subjugated new territories, they appointed new curacas, capacs, and sinchis or forced existing ones to swear allegiance to them. They chose these leaders from among local men, unless they suspected them of anti-Inca sentiments, in which case, they appointed men from the royal ayllus of Cuzco (Moseley, 1992).

The high society in imperial Cuzco closely reflected this general Andean model. The city of Cuzco was occupied almost exclusively by about a dozen ayllus that claimed the first Inca, Manco Capac, as their common ancestor. These ayllus were divided into two moieties, Hanan (Upper) Cuzco and Hurin (Lower) that lived in two different areas of Cuzco (Cobo, 1979). Their emperor, who held the title of Sapa Inca (“Only Inca”), was customarily elected by the leaders of the ayllus. He was usually a son or close blood relative of the previous Sapa Inca, who often nominated him as his successor. However, the leaders of the Cuzco ayllus did not have to accept the Inca’s choice and could appoint another man, as long as he came from the Inca’s lineage. This probably explains why almost every time a new Inca was selected, there were rival candidates for the post and the new ruler, if he was capable, had to squash plots against him and execute or exile dissenters. Sometimes, as in the case of Viracocha, the reigning Inca supported the losing candidate, which led to further friction or out-and-out civil war. Periods of dual leadership were also common. Thus, Viracocha was co-emperor with his son Urcos and later with his son Inca Yupanque, later known as Pachacutec, who shared power in his later years with his son Tupa Inca Yupanque. Tupa Inca’s son, Huayna Capac, who campaigned extensively in the north of his empire, put his cousin in charge of the administration of the empire in Cuzco (Cobo, 1979; Betanzos, 1996; Moseley 1992).

Although the Incas recognized the various ethnic and kinship groups under their rule, for administrative expediency they also organized them according to a decimal system. Thus, the administrative ayllu comprised 100 pachacas, or lineages, each headed by a purej or family head. Sometimes, the ayllus were further subdivided into units of 10 and 50 pachacas, whose leader was appointed by the curaca of the ayllu. Five ayllus formed a pihcapachaca (500 pachacas) led by a pihcapachaca curaca. Two pihcapachacas or 1,000 pachacas formed a waranka whose leader was a waranka curaca. Ten warankas formed one huno administered by the huno curaca who collected population data from his subordinates and reported directly to the Inca. He was assisted in this work by the quipucamayocs (Moseley, 1992; Kauffmann-Doig, 1980).

Generally speaking, personal property did not exist in the pre-Columbian Andean region. The land belonged to the ayllu and the curaca allotted a plot (topo) to each family. At the death of its holder, a topo reverted to the ayllu. The territory of the ayllu, called marca, varied in size, depending on the region and the resources available. In areas with poor rainfall or soils, the marcas tended to be large, whereas in fertile valleys, they tended to be smaller. Typically, they occupied various elevations, so that the ayllu could exploit various ecological niches. Each topo also spread over various elevations, so all the families of the ayllu could have equal access to all the ecological niches. When the Incas came to power, they laid claim to all the land in the name of the state and Inti, the sun god, but allowed the curacas to continue apportioning the land as they had always done. The size of a marca was now large enough to provide 100 families with plots. A variable number of marcas formed a sector called a saya, and an undetermined number of sayas made up a huamani or province. These provinces corresponded roughly to the territories of the tribes or city-states conquered by the Incas and retained their old names and capitals. The provinces, in turn, made up the four suyos of Tawantinsuyu: Collasuyu, Cuntisuyu, Antisuyu, and Chinchaysuyu (Kauffmann-Doig, 1980).

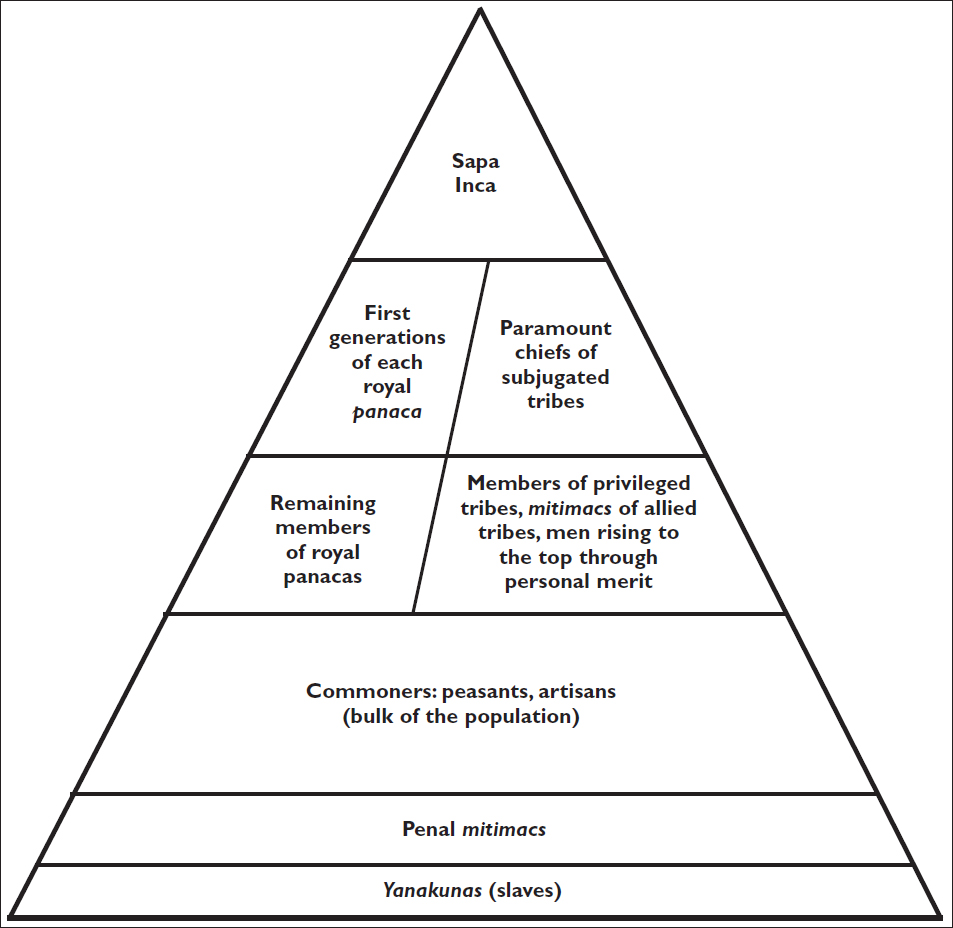

In addition to the ayllus, based on kinship ties, Tawantinsuyu society was divided into a pyramidal structure with the Inca at the top. Below the ruler was the aristocracy formed by the ayllus of Cuzco. These noblemen were called orejones (big ears) by the Spaniards because they wore enormous gold earplugs in their earlobes. It is from this class that the Inca army drew most of its cadre and its elite units as well as its administrators and governors.

The common people were called mitimacs (taxpayers) or runas. They provided the Incas with the labor and goods necessary to run the empire and the bulk of their army. The lowest class was constituted by the yanakunas (servants or slaves) who served the Inca, his relatives and the Cuzco nobility. They were usually prisoners of war or transplanted artisans from the conquered provinces.

Social pyramid of Tawantinsuyu

The Sapa Inca, who was considered to be the direct descendant of Inti, the sun god, was at the top of the social pyramid. All the land of the empire belonged either to him or to his ancestor, the sun god. The highest-ranking people below him were the sons and daughters of his predecessor, who lived in the compound of the deceased Inca and tended to his needs. Paramount chiefs of kings who had surrendered to the Inca retained their high status, and answered directly to the Sapa Inca. Subsequent generations of deceased Incas lost some status, but still enjoyed a privileged status in Inca society. Members of closely allied tribes enjoyed the same status as the Incas, even when they were transplanted into different parts of the empire as mitimacs, whose role was to pacify the locals. Outstanding military leaders and administrators could rise from the ranks of the commoners to this level of society. The bulk of the population of Tawantinsuyu consisted of commoners, who provided the Inca with goods and services. At the bottom of the pyramid were rebellious subjects who were forcibly transplanted from their original homelands, and yanakunas who served as personal slaves to the upper classes. All these classes were further subdivided into ayllus (clans) grouped into two moieties: Hanan and Hurin. (Chart after Kauffmann-Doig, 1985.)

Andean social organization

In addition to being organized in social classes, Andean societies were organized into kinship groups that relied on each other for help with agricultural chores as well as protection and warfare. The Incas used this social structure to organize their armies.

The mit’a was the name given to the labor obligation owed by one family to the other in the ayllu system. With the advent of city-states and state societies in the Andes, it became a common form of taxation. The local curacas, capacs, and sinchis gave the families of the ayllus food, textiles, and other goods and services, and in return they gave a percentage of their labor. If they were skilled artisans, they gave the products of their shops. The most prized items were textiles and ceramics. Gold and silver jewellery and vessels were also highly coveted. The curacas stockpiled them in their storehouses and used them to buy influence and power (Moseley, 1992; Kauffmann-Doig, 1980).

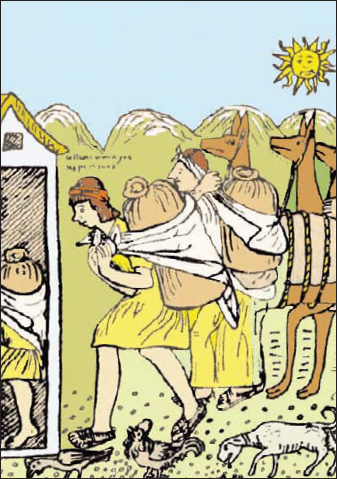

An Inca envoy in court dress carrying the insignia of his office. The men appointed to such roles were carefully chosen by the Inca. They were usually his close kin – a brother, uncle, or first cousin – and they were completely loyal to him.

An engraving by Guamán Poma de Ayala showing the Inca general Aucaruna attacking a pukara.

The Incas used the mit’a in the same way as their predecessors, but devised an elaborate system to stockpile and redistribute the products of the land. In every village and town they built rows of stone colcas or well-ventilated storehouses for maize, freeze-dried potatoes and meat, llama wool, textiles, ceramics, arms, and other products. Round colcas were for storing maize, square colcas were for storing tubers and other goods. The colcas, which stood on high ground so that their contents remained dry, were visible from miles away. They were periodically replenished by the local curacas, who collected the goods from the members of their ayllus. Before the new crop came in, the colcas were emptied and their contents were sent to Cuzco, which was surrounded by warehouses holding incredible amounts of goods. Careful records of crops, goods, and labor days were kept by the quipucamayocs (Moseley, 1992; Kauffmann-Doig, 1980).

The colcas, located in every regional capital of the empire, served to store food and clothing for the local population in times of crisis; men and women working on public works; and the Inca’s armies on the march. The colcas in Cuzco supplied not only the noble lineages living there, but also a veritable army of potters, weavers, metalworkers, and other artisans that lived in the periphery of the capital. Whenever the Incas conquered a new city, they sent its best artisans to Cuzco to work for them (Moseley, 1992).

The Inca General Apocamacinga is shown battling with Chilean tribesmen in this engraving by Guamán Poma de Ayala.

The mit’a also supplied the Incas with a vast labor force for all public work, including the construction and maintenance of agricultural terraces, irrigation canals, roads, bridges, tambos, colcas, palaces, temples, and fortresses. It also supplied a ready supply of conscripts for their armies. The local curacas were required to raise work gangs, supervise their work, and report the number of days each person under their authority toiled for the state and the temple. In the case of a road, each ayllu was responsible for the section passing through its territory. More ambitious building projects, such as bridges or tambos, required the participation of units larger than the ayllu. All able-bodied men and women were expected to serve according to their abilities. Only toddlers, the very old, and the infirm were exempt from service. Typically, the mit’a consisted of 10 percent of a subject’s time. Failure to render the mit’a was punishable by death. In exchange for the work, the curaca was required to supply his crews textiles, food, chicha, and coca leaves from the colcas. Mit’a service was also accompanied by feasting and drinking to make the work less onerous (Moseley, 1992).

According to Betanzos, Cobo, and Sarmiento de Gamboa, the Incas were able to raise armies of 100,000 men without undue difficulty. Except for the garrisons of some border outposts, these men were not professional soldiers, but aucak camayocs (men fit for war) between the age of 25 and 50. Each ayllu was expected to supply a predetermined number of men when the call to arms went out and send them out to Cuzco or some other point on the road. Although there was no time limit for military service, the eligible men of each ayllu took turns in this service. The men who remained at home tilled the lands and took care of the households of those who were gone (Kauffmann-Doig, 1980; Heath, 1999; Fresco, 2005).

The soldiers were assigned to units of their own kinsmen and were led by officers from their own or a closely related ayllu in conjunction with an orejón from Cuzco. The men of each unit wore the characteristic dress of their hometown and bore the armament of their region. Thus, the Anti and the Chuncho of the east used bows and arrows, whereas the Wanka carried spears and slings, and the Cuzquenos carried bola stones, clubs, and maces. The soldiers were usually accompanied by their wives and children who served them on their marches (Heath, 1999; Fresco, 2005).

The Incas were also careful to use their troops in familiar terrain. Thus, they seldom committed lowlanders to service in the mountains, where they would suffer from mountain sickness and be a liability rather than an asset. Likewise, they kept the highland troops used to the grasslands of the Altiplano out of the dense forests of the eastern slopes of the Andes where their clubs and maces had little effect against the bows and arrows of the forest tribes (Cobo, 1979; Betanzos, 1996).

The units were organized on a decimal basis, like the civilian administrative units of the empire. It is not known whether the units of the army had specific names, but the titles of the commanders were recorded by the Spanish chroniclers of the 16th century. The lowest two ranks, chuncacamayocs and pihcachuncacamayocs, were held by local leaders, no doubt the curacas of the ayllus and of the towns and villages, who were responsible for providing the men with clothing, armament, and supplies. On the road, the soldiers got their supplies from the colcas, and either rested in the tambos or near them. A huge herd of llamas led by herders followed the army and provided it with meat. It is estimated that the Incas required 10 to 15 llamas per soldier (Betanzos, 1996; Heath 1999; Fresco, 2005).

The elite units consisted of two huaminca (veteran) divisions – one from Hanan Cuzco and the other from Hurin Cuzco – whose men were trained as warriors from the age of 14 or 15. Their captains, men who had risen through the ranks and distinguished themselves in action, were called aucapussak. Since the rivalry between the two divisions was intense and could escalate into violence at times, they were often kept separate on the march and at rest (Heath, 1999).

The highest-ranking officer in the Inca army, the aucacunakapu (chief of soldiers), came from Hanan Cuzco and next highest-ranking ranking officer, the aucata yachachik apu (chief in charge of organizing the soldiers), came from Hurin Cuzco. Ian Heath explains the other ranks structure:

Other senior officers included the hinantin aucata suyuchak apu (chief who assigns troops to their proper place), equivalent to a European sergeant-major of that period, and the Sericac or quartermaster. The commander of an army in the field, called an apusquipay, had an aide called apusquiprantin. The apusquipay was usually the uncle, brother, or some other close kinsman of the Sapa Inca.

An engraving by Guamán Poma de Ayala showing the Inca general Inga Maitac attacking a pukara of the Yungas. The Inca troops are carrying a golden statuette of the Sun God into battle.

The garrisons of the border outposts in the north and the south, called arccak sayapayak, were at first made up of Cuzco huamincas. Once the area was pacified, they were replaced with local troops on mit’a service, who took turns manning the pukaras. However, the commander of the pukara was invariably a veteran from the Cuzco area, assisted no doubt by the local chuncacamayoc or pihcachuncacamayocs. The size of the garrisons depended on the size of the fort. It is estimated that a small border outpost may have been occupied by the smallest unit of the Inca army: ten men and their two commanders. Larger pukaras probably held larger units (Fresco, 2005). Early Spanish chroniclers reported that the fortress of Sacsayhuamán at Cuzco held as many as 5,000 men (Frost, 1984).

The building and maintenance of pukaras, like every other public work project, was the responsibility of the curacas and their ayllus. However, it is likely that the Sapa Inca commissioned the design of the fortresses and sent a clay model of it to the curaca, who took charge of the construction.