During the period preceding Inca hegemony the Andean people engaged in a flurry of fortification building, which indicates that competition for limited resources, and warfare, had increased substantially. As they conquered the kingdoms surrounding them, the Incas quickly learned the value of fortifications and added their own to the existing defences or built their own fortified systems to hold their newly conquered territories. Thus, there were few towns in Tawantinsuyu that did not have some type of defences. In the circumstances, it is impossible to cover the entire inventory of Inca fortifications in this volume. The present list, therefore, includes only the most famous sites and some of the most typical of their genre. A complete list would probably require several large volumes.

In must be pointed out that the most common feature in Inca fortifications was the defensive terraces. These resembled the agricultural terraces, but were higher and narrower and were surmounted by parapets, which have for the most part disappeared, leaving only low projections to indicate that they had been there. Another feature common to the Inca fortifications was that they cunningly conformed to the terrain, making the most of the advantages offered by differences in elevations and irregularities of the terrain. In addition, most Inca pukaras had three types of functions: administrative, religious, and military. Usually, the administrative buildings, which included warehouses, the religious structures, and the quarters for the troops were located at the top of the hill, at the center of the pukaras. The size of these administrative-religious-military complexes varied according to the size and importance of the site (Fresco, 2005).

Starting with Inca Pachacutec, the Incas adopted the strategy of building strongholds in newly subjugated areas in order to maintain control over them. Sometimes, they took over and adapted existing fortifications, at other times they built entire strongholds from scratch.

The Cuzco Valley represented the heartland of Tawantinsuyu and it contained their most significant shrines. It was the area that was first subjugated by the Incas of Cuzco and had become so totally integrated into the Inca social fabric that it became the source of their most trusted officers and troops. The Cuzco fortress area included the oldest and probably the least standardized fortifications of the empire. Whatever lessons they learned from building these fortifications, the Incas applied them to the construction of later strongholds.

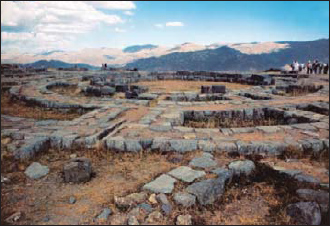

The defensive terraces at Sacsayhuamán near Cuzco with the remaining sections of the parapets.

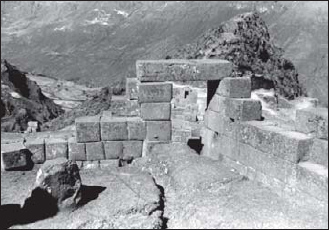

The foundations of one of the three large towers at Sacsayhuamán. This circular structure had several levels. Some believe it was used as a storage area, administrative center, or even a palace, but there are no accurate records. The Spanish claimed that the Incas had fighting positions on the top and used them to considerable effect during the Spanish attack on the fortress.

The cyclopean terraces of Sacsayhuamán.

A “zigzag” in one of the defensive terraces of Sacsayhuamán, seen from above.

The three zigzaging defensive terraces of Sacsayhuamán are said to form the plumage of a hawk’s head.

Sacsayhuamán

Sacsayhuamán was probably the largest and most prestigious fortress of the Incas. Its construction is variously ascribed to Pachacutec or his son Tupa Inca, who decided to defend the capital the way other Andean chieftains defended theirs. Although what remains of it today is quite impressive, its ruins cannot give the visitor an accurate idea of what it looked like at the peak of its existence in 1534. Indeed, it was dismantled stone by stone during the 300 years of colonial rule, as the Spanish plundered it to build their palaces and churches.

One of the best descriptions of Sacsayhuamán in its heyday was by Pedro Sancho, Pizarro’s secretary:

On the hill, which is round and very steep on the side facing the city, there is a very beautiful fortress of stone and earth with big windows that look over the city and make it look even more beautiful. There are inside it many apartments and a keep in the middle of it, built in the form of a cube with four or five bodies, placed on top of each other. The rooms and apartments inside it are small and the stones from which it is made are very well cut, and so well fitted to each other that there appears to be no mortar; and the stones are so smooth that they seem to be brushed slabs, with jointure of the type used in Spain, one joint against the other. They have so many rooms and towers that one could not see them all in one day; and the Spaniards who have travelled in Lombardy and other foreign kingdoms say that they have not seen another building like this fortress, nor a stronger castle. Five thousand Spaniards could stay inside: one cannot shoot at it with a cannon, nor mine it because it is located on a cliff.

On the side of the city, which is a steep hill, there is no more than one wall; on the other side, which is less steep, there are three, one higher than other, and the last one, inside, is the highest of all. The most beautiful thing one can see in terms of building in that land are these walls because they are made of stones so large that no one who sees them can say that they were put there by human hands, for they are as big as chunks of mountains and hills. Some are thirty hand-palms high and as wide; others are twenty-five or fifteen palms wide. None is so small that three carts could carry it. These stones are not smooth, but they are very well fitted and joined together.

The Spaniards who see them say that neither the bridge of Segovia, nor any other building Hercules of the Romans built are as worthy of being seen as this one. The city of Tarragona has a few walls made in this style, but they are neither as strong nor as big. These walls make turns so that if one was to shoot at them, one could not make a direct hit but rather a glancing blow from the outside. These walls are made of the same stones, and between one curtain and the other there is earth, and so much of it that three carts abreast could move on top. They are made on three levels in such a manner that where one begins, the other ends. This entire fortress was a depot of armament: clubs, lances, bows, arrows, axes, shields, strong quilted doublets of cotton [cotton armor], and other kinds of weapons, and clothes for the soldiers, collected here from all the lands subject to the Lords of Cuzco. They had many colors: blues, yellows, and brown and many others to paint with; clothes; and a lot of tin and lead and other metals; a lot of silver and some gold; a lot of capes; and quilted doublets for the warriors. [Sancho, 1962: 660]

The fortress was situated to the north of Cuzco, 3km from the central plaza. It is roughly shaped like the stylized falcon head often found on Inca pottery and textiles. As in most Inca fortresses, its walls actually consisted of terraces with massive retaining walls topped by stone parapets. Its three zigzag-shaped northern walls, which face away from the city, are 300m long. The zigzags probably had the same function as bastions in European fortifications, providing flanking defence. However, the wall projections were set closer together than the bastions of European forts of that period because the Incas only had close-range weapons, such as lances, bola stones, slings and hand-thrown stones instead of bows and arrows or guns. The cyclopean blocks of stone that had awed Sancho so much were 9m high, 5m wide, and 4m thick. They came from a nearby granite quarry and each weighed about 360 tons. They were used mainly in the first wall. The two higher walls were made of slightly smaller blocks. Three gates protected the access to the earthen ramps behind the defensive walls (Kaufmann-Doig, 1980; Frost, 1984). As in other pukaras, the entrances to Sacsayhuamán may have been protected by stone chicanes and small square towers, which have now disappeared without trace (Fresco, 2005).

The southern wall of Sacsayhuamán was made of smaller stones and overlooked the city. It was not as strong as the other three walls because it stood over a cliff, which provided protection in itself. In the battle for Cuzco in 1536, the Spanish forces opted for scaling the triple wall rather than this cliff with the single wall. In addition to its defensive function, the southern wall of Sacsayhuamán had a religious function, probably similar to the three windowed wall at Machu Picchu. It is thought that the windows aligned with the sun, the moon and a star or a planet during the solstices and equinoxes, allowing the ruling class of Cuzco to pick the best planting and harvest times for their subjects.

Between 1930 and 1934, Peruvian archaeologist L.E. Valcárcel uncovered the foundations of three round structures in the enclosure on top of the hill. Based on oral tradition he called them Muyacmarca (round enclosure), Sayacmarca (water enclosure), and Paucarmarca (beautiful enclosure). It is thought that these three buildings or towers were probably administrative and religious rather than defensive structures. As Sancho mentioned in his chronicle, Sacsayhuamán also served as a large arms depot that probably supplied the two Hanan Cuzco and the Hurin Cuzco divisions. Sancho also noted that the city of Cuzco was surrounded with numerous warehouses, where enormous amounts of goods, including armaments, were stockpiled. In addition to temples and warehouses, Sacsayhuamán enclosed palaces for the Sapa Inca and the Inca aristocracy because it was supposed to become the last refuge for them in the event that Cuzco ever put under siege. Thus, like most pukaras, large and small, Sacsayhuamán combined military, spiritual, and administrative functions, which were inextricably intertwined in Andean culture.

Puka Pukara

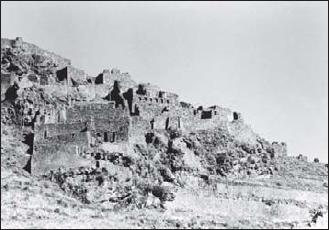

Puka Pukara or “Red Fortress,” located approximately 7km from Cuzco to the northwest of Sacsayhuamán, guarded the approaches to the capital from the direction of Chinchero and Pisac, and particularly Anta, home of the Incas’ arch enemies, the Anti. It was built on a hill overlooking an important crossroad, and was made mostly of local porphyry, the color of which gave it its name. Like most pukaras, it had spiraling defensive terraces that had held parapets at one time. Stone chicanes and towers guarded the access to each level. As usual, living quarters, administrative buildings, storehouses, and a shrine occupied the top of the hill. Today, the defensives structures of Puka Pukara are often ignored in favor of the rather uninteresting structures on top.

Tambomachay

Tambomachay is located 1km to the northeast of Puka Pukara. The name of this site derives from two Quechua words: tambo or rest stop and machay or cave. However, the site contains no caves or structures typical of a tambo. It consists mainly of terraces and retaining walls with trapezoidal niches. Some authors have suggested that it might have been a spa of the Incas, since it has two water channels that drain the terraces. However, Kauffmann-Doig has pointed out that its terraces, which are very similar to other defensive terraces, and its proximity to Puka Pukara seem to suggest that the primary function of Tambomachay must have been military. However, as is often the case with Inca structures, it may well have held some religious significance as well.

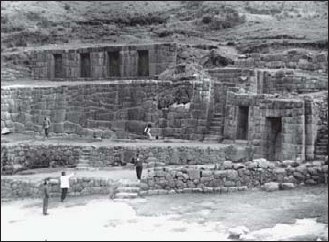

Puka Pukara – the “Red Fortress” – derived its name from the color of the hematite from which it was built. In the photo the enclosure of its religious administrative-military complex can be seen.

Tambomachay, despite its name, was not a tambo; it was an outpost that guarded the approaches to Cuzco together with Puka Pukara.

The “Sacred Valley” of the Incas comprises the stretch of the Vilcanota River that takes on the name of Urubamba as it passes by the eponymous city. On each end, the Sacred Valley is guarded by two of the largest strongholds in Tawantinsuyu: Pisac and Ollantaytambo. The valley not only held religious significance for the Incas, but was also a major trade and communication route leading to Cuzco and its environs, and thus held enormous strategic importance. These, no doubt, were the main reasons why the Incas dedicated so much effort to the construction of the two large administrative-religious-military complexes of Pisac and Ollantaytambo.

Pisac

Situated approximately 60km to the northeast of Cuzco, Pisac guarded a gorge on the Vilcanota River. The original settlement, which probably pre-dated the Incas, overlooked the flood plain on the west side of the river, between two tributaries of the Vilcanota: the Río Quitamayo and Río Chongo. The villagers raised their crops on the flood plain, which was irrigated by a network of canals, and on terraces that fanned out from the outcrop where the original village stood to the bottom of the slope overlooking the Río Chongo. These terraces are flanked by a steep ravine and two more sets of terraces on the eastern slope of the ridge formed by the two streams. In more settled times, when the villagers no longer feared incursions from rival clans, they moved into the river valley, closer to the main road to Cuzco and Urcos. On the ridge above the old village, the Incas built an impressive administrative-religious-military complex that controlled the river and the road in the valley and defended the approaches to Cuzco.

Pisac was by no means a typical pukara. It actually consisted of five groups of buildings and other defences that straddled the entire ridge. On the lower elevations, defensive terraces guarded the road and the approaches to the gorge. They were backed by two towers. Further up stood four walled complexes, each at a higher elevation than the other, that encompassed the usual array of living quarters, storehouses, administrative facilities, and religious buildings. Each of the complexes was accessed through massive gates. A trail linked the village and all the defensive elements to each other. Defensive walls protected this trail at various points where the slope of the ridge was not steep enough to deny access.

Another view of Tambomachay.

A view of the old town at Pisac from above.

Pisac

The fortified complex of Pisac stands on a ridge overlooking the Vilcanota River at a point where it passes through a narrow gorge. This strategic location allowed it to control an important trade route that linked the coast to the highlands. The Inca site grew around a pre-existing village built on a spur of the ridge overlooking a set of semi-circular agricultural terraces. Like most fortified Inca sites, Pisac combined administrative, religious and military functions. Just above the old village (1), the Incas built the Intiwatana (“hitching post of the sun”) enclosure (2), which included a temple dedicated to the Sun (3), colcas (storage houses), and quarters for the troops. Later they built three more complexes higher on the ridge as well as guard towers and walls to protect the approaches to each of the complexes from the valley floor.

The rear gate at Pisac.

This is a guard post on the access trail to Pisac.

Looking down on the Temple of the Sun complex at Pisac.

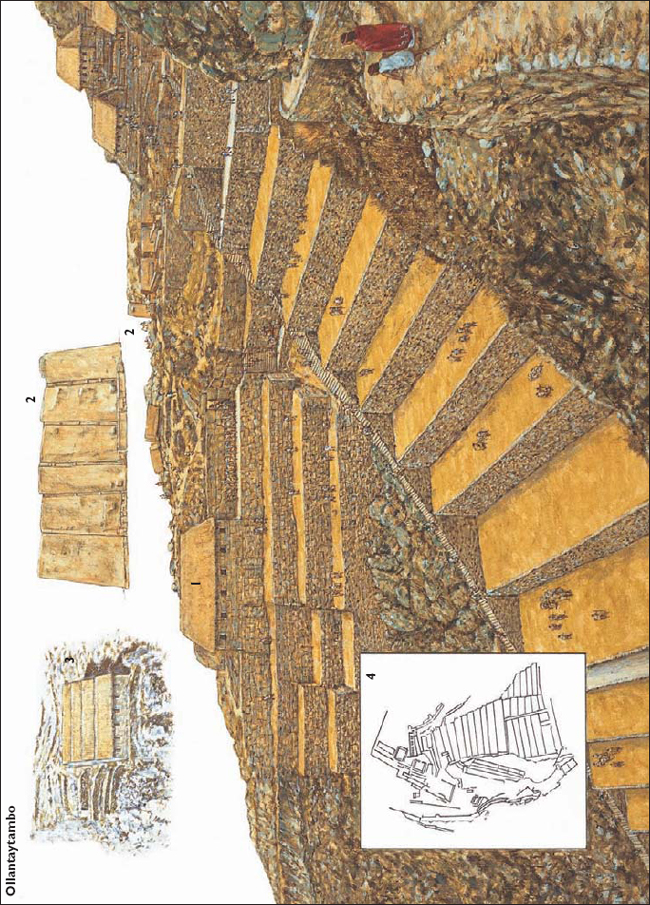

Ollantaytambo

Ollantaytambo, located approximately 75km to the northeast of Cuzco in the Urubamba River valley, was the first massive administrative-religious-military complex that guarded the Antisuyu road. It is located at the confluence of the Urubamba and Patachanca rivers, at the intersection of two major trade routes; it lies across the river from the Inca town, to which it was connected by a suspension bridge with massive stone buttresses. Like Sacsayhuamán, this fortified complex probably served as a place of refuge for the local population in case of war. It also served as a royal tambo for the Inca and its numerous warehouses stored abundant supplies for the Inca army on the march.

Although the Incas took sole credit for its construction, its sheer size and complexity and the fact that its main defences face Cuzco lead most contemporary Peruvian archaeologists to question that claim. Local oral tradition and even Inca oral history seem to confirm the Peruvians’ hypothesis, for they mention fierce battles fought between the original inhabitants and the Incas under the reign of Pachacutec as well as a bloody rebellion led by a general called Ollantay. However, the defences of Ollantaytambo may well have faced Cuzco to protect Vilcabamba and its resources from Altiplano Indians rather than hostile tribes from the Amazon.

According to an Inca legend, the town was named after Ollantay, a general of the Inca army who fell in love with one of Pachacutec’s numerous sisters, and was denied her hand due to his non-Inca lineage. The thwarted lover returned to his hometown and incited its inhabitants against Pachacutec. After a protracted siege, the brave general was betrayed by Rumiñawi, an Inca officer, and captured. However, by then Pachacutec had died, and his successor, Tupa Inca, awarded him his beloved’s hand in marriage. Ollantay was appointed castellan of the place. It is more likely, however, that Tupa Inca offered Ollantay his sister in marriage in order to forge an alliance with him and end a rebellion that was getting out of hand. When Pachacutec died, Ollantaytambo became part of his panaca (estate and household of dead Incas), but, very likely, also continued to serve as a tambo and administrative center for subsequent Incas and was continuously reinforced and developed. After the siege of Cuzco in 1536, Ollantaytambo briefly served as Manco Inca’s capital.

A view from inside the temple area at Pisac with the huaca or sacred stone in the left foreground.

The ruins of the town of old Pisac seen from below.

During Inca times, the approaches to Ollantaytambo along the Urubamba River were covered by pukaras at Pachar, Choqana, and Inkapintay to the east, and at Choquequillca and possibly at Wayraqpunku to the west. However, this last pukara may have been destroyed when a train station was built there. Another pukara at Pumamarka on the Patacancha River guarded the approaches from the north. The administrative-religious-military complex of Ollantaytambo was situated to the west of the town, and probably served as a place of refuge for the local population in case of war. Choqana and Inkapatay were located at opposite ends of a meander of the Urubamba, forcing the enemy to cross the river twice if he wanted to pass through. On top of the ridge of Pinkuklluna, the Incas built a string of small outposts with a good view of the Urubamba as well as the Patacancha river valleys. Any travellers approaching Ollantaytambo could be spotted long before they arrived at their destination (Protzen, 1993). No doubt, the guards employed smoke signals to alert the garrison of the fortress.

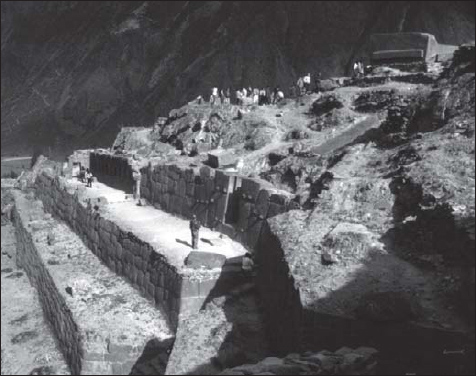

The administrative-religious-military complex of Ollantaytambo was situated on a ridge overlooking the town in the valley floor. It was covered by defensive walls on the northwest side, where there were no natural defences to speak of and on the south side, where the hill was not steep enough to provide adequate protection. Access from the north-northeast was barred by a formidable barrage of 11 defensive terraces, which no longer have any parapets. However, it is likely that such parapets did exist, as in other Inca sites, and that they were pulled down by the Spaniards who were determined to make Ollantaytambo indefensible. A steep staircase to the south of the terracing allowed access to the enclosure on top of the ridge and to the terraces. It was defended by the T’iyupunktu Gate, which still stands, and a wall, which has been dismantled. It is here that the Spanish expeditionary force led by Pedro Pizarro was defeated in 1536 by the forces of Manco Inca.

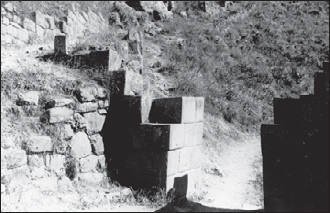

The upper levels of the defensive terraces at Ollantaytambo.

The defenses of the Ollantaytambo area. (Joe Kaufmann)

The access trail and terraces at Ollantaytambo, showing the Temple of Ten Niches in the lower center-right, and the unfinished Temple of the Sun in the center-left.

Ollantaytambo

Ollantaytambo is arguably the second most important Inca site after Machu Picchu and it lies at the opposite end of the Sacred Valley from Pisac. The site includes the Temple of Ten Niches (1), and the unfinished Temple of the Sun (2), which comprises a wall of six stones over 13ft high (also shown as an inset). Pinkuklluna (“the mountain of flutes”), which faces the ruins across the Patacancha Valley, features several large storage houses (3). On the “backside” of Ollantaytambo massive walls had to be built to shore up the site. A plan view is also shown here (4).

A close-up view of the terraces at Ollantaytambo, below the Temple of Ten Niches.

The enclosure on top of the hill, which included living quarters, storerooms, and large square rooms, was still unfinished when Francisco Pizarro conquered Peru. The function of this complex is unknown, and it has been speculated, without much evidence, that it might have been a temple dedicated to the sun. However, this complex, which was called Fortaleza (fortress) by the locals and the Spaniards, shows no sign of worship or sacred objects. It is likely, therefore, that it was indeed an unfinished keep built to serve as a refuge for the people of the town in the valley (Kaufmann-Doig, 1980; Frost, 1984; Protzen, 1993).

The Antisuyu Road, which linked the Vilcabamba province to Cuzco, was the shortest but the most heavily fortified road of Tawantinsuyu. It served the Vilcabamba province, which bordered the territories of the fierce, bow-and-arrow wielding Amazonian tribes that the Incas had not been able to subjugate. In addition, Vilcabamba was a source of tropical flora and fauna and silver ore, much prized by the Andean Indians, including those dwelling as far as the Pacific coast. Control of the production and/or distribution of tropical fruits, coca leaves, feathers from bright-plumed birds, puma pelts, and silver not only supplied the Incas with much coveted luxuries, but also gave them power over their subjects, who were rewarded for faithful and competent service with these precious gifts. For these reasons, the Incas jealously guarded the Antisuyu Road with a series of pukaras. When Manco Inca revolted against the Spaniards, he withdrew into the mountain fastnesses of Vilcabamba precisely because it was so heavily fortified and because the rough terrain made it easy to defend.

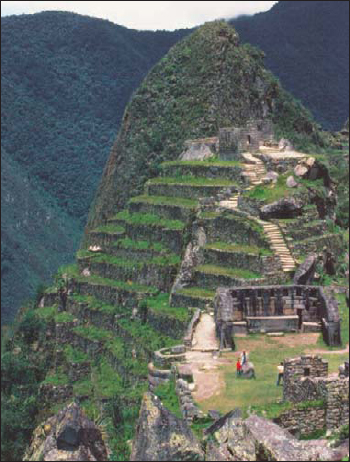

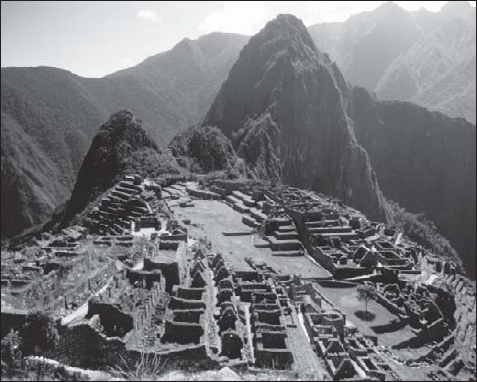

Machu Picchu, probably the best-known Inca site, is located on a mountain peak some 110km to the northwest of Cuzco, at 2,700m above sea level in the Vilcabamba mountain chain. It overlooks the Urubamba River on one side and an Inca trail leading to the site of Choquequirau. It seems to be guarding this road at this point with two other pukaras: Huayna Huiñay across the valley, and Huayna Picchu just behind it.

Its architectural style suggests that it was built during the Inca imperial period, and its construction is generally attributed to Inca Pachacutec, who subjugated the region. Since Machu Picchu was unknown to the Spaniards, Peter Frost suggests that it must have been abandoned and forgotten by the time the Spaniards conquered Peru. Frost estimates that the site “was built, occupied, and abandoned in the space of less than one hundred years” (1985: 93). In its heyday, Machu Picchu sheltered as many as 1,000 people housed in 200 habitations.

The function of Machu Picchu has been a subject of contention among archaeologists for many years. Hiram Bingham, who discovered the site in 1911, assumed it was a fortress with military functions because of its location and the presence of walls, a dry moat, and defensive terraces around all the accessible parts. Later archaeologists rejected his theory, favoring instead the idea that Machu Picchu was a religious center. Its location on a mountain peak overlooking the Urubamba River and an important Inca trail seems to support Bingham’s theory. Defensive terracing surrounding the settlement on top of the hill is also an indication that Machu Picchu had an important military mission in its heyday. On the other hand, the presence of temples and numerous storerooms indicates that it was also an administrative and religious center, thus combining the three functions, like most Inca pukaras and larger fortresses.

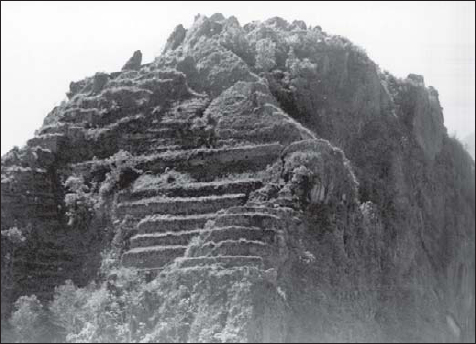

On a peak nearby, about one hour’s walk away, stands a small outpost called Wayna Picchu, discovered in 1936. Its approaches are covered by “ancient terraces, so inaccessible and so narrow that their value for agricultural purposes would have been negligible,” says Frost, adding that “these were probably ornamental gardens” (1984: 103). However, it is unlikely that the Incas would have dedicated much time and effort to building gardens in such an improbable place. These narrow terraces were more likely built to defend the small outpost, which overlooked both the Urubamba River valley and Machu Picchu.

Not far away stands the outpost of Intipata at an elevation of 2,800m. It was discovered in 1941. It consists of 48 terraces, four sets of stairs and 23 enclosures or canchas with trapezoidal niches in the walls, typical of Inca architecture (Kauffmann-Doig, 1980).

Huayna Picchu, the modest outpost guarding Machu Picchu, showing its small defensive terraces.

The Vilcabamba fortress area. (Joe Kaufmann)

Across another valley that opens into the Urubamba and to the southwest of Machu Picchu stands Huayna Huiñay, another larger Inca outpost, also discovered in 1941. This settlement was built on two levels, with intervening terraces. It includes 30 rooms facing to the southeast and to the west and ritual baths. A terrace and some of the walls of the settlement stand over a cliff that drops almost vertically to the valley floor (Kauffmann-Doig, 1980; Frost, 1984).

With its three satellite outposts Huayna Picchu, Huayna Huiñay, and Intipata, Machu Picchu formed a barrier across the valley and protected the trail to the Urubamba River. It was probably built by Inca Pachacutec to secure the territories he had just conquered. As he pushed relentlessly forward, Pachacutec built subsequent lines of fortifications. Machu Picchu remained in the rear, losing its strategic importance, and was abandoned. This strategy seems to be consistent with the methods adopted by Pachacutec’s son, Tupa Inca, and grandson, Huayna Capac, in the northern and southern reaches of their empire (Fresco, 2005).

Machu Picchu, the last refuge of the Virgins of the Sun.

The fortress area of Vilcabamba is not very well known, since most of its components were only discovered during the 20th century, some as late as 2000. Since they are located in the area called Montaña, they were swallowed up by the tropical mountain vegetation almost as soon as they were abandoned. In some cases, their existence was unknown to the Spaniards; in others, it was forgotten during the colonial period. Clearing an excavation at this site is still ongoing, and many of their peripheral areas, where the defensive terraces and walls are most likely to be, are still shrouded in vegetation.

A view of the Urubamba Valley from the walls of Machu Picchu. The road in the background leading up from the valley floor is a modern one.

As Pachacutec moved the borders of his empire further eastward, he built a series of strongholds on the Vilcabamba River, an important tributary of the Urubamba. Going from Ollantaytambo towards the Amazon basin, the first pukara in this group is Vitcos, thought to be the last capital and stronghold of the Incas. It stands on the Vilcabamba River, on the main Inca road from Ollantaytambo. Its three-fold mission was to control the region, oversee its economic production and its population, and provide religious services for the locals and the army units passing through the area. Like Machu Picchu and Ollantaytambo, it was surrounded by satellite outposts. These included Yupanca, Llucam and Puquiura to the north, and Huancacalla, to the south. All these sites were strung along the Vilcabamba River. However, since the area has been engulfed by vegetation, the exact number of outposts and their nature is unknown. Recent new finds in the area indicate that there might have been more.

The next group of settlements and fortifications lies further up the Vilcabamba River, near its confluence with a smaller mountain stream. It includes the strongholds of Espíritu Pampa, Vilcabamba the Old, and Marcanay. The Espíritu Pampa group was the easternmost Inca outpost in the Vilcabamba region and stands the closest to the Incas’ nemesis, the bow-and-arrow wielding Anti tribes of the Amazon. Like the others, these strongholds were administrative-religious-military complexes.

In the region along the coast of the Pacific, the Incas built few, if any, strongholds of their own mostly because they conquered a series of coastal kingdoms that had already constructed suitable complexes. One of the most powerful of these kingdoms was the Kingdom of Chimú run by warrior-priests who had established their capital at Chan Chan. Apparently Inca Pachacutec was profoundly impressed by the splendor of the Chimú, for he adopted many of their customs and administrative practices. Apart from some minor architectural additions and the construction of an ushnu (altar) dedicated to the sun, the Incas left most of the coastal strongholds and outposts intact, incorporating them into their empire.

The overall layout of Machu Picchu.

Tambo Colorado

Tambo Colorado, also known as Pucatambo, Pucallacta or Pucahuasi (“red tambo”) is situated on the old Inca road, in the Pisco Valley, about 270km to the south of Lima. It was probably a pre-Inca settlement that grew along an important trade route. After the Inca Pachacutec took it over around 1450, he transformed it into a tambo where he could rest and re-supply his armies. Apparently, Tambo Colorado played an important role in the wars with the coastal states during the reigns of Pachacutec and Tupa Inca.

Tambo Colorado is made of red adobe bricks, a common construction material in the area. However, it also incorporates architectural elements of the Inca traditions like trapezoidal niches and doorways. It consists of three main sectors built around a trapezoidal plaza and it is intersected by an Inca road that links the coastal highway to the Sierra highway.

Like most Inca settlements of this type, it was an administrative-religious-military complex. The southwestern sector, which is the smallest, stands apart from the other two. It consists of a large enclosure with walls on three sides that opens onto the dry bed of the Pisco River. In the northeast corner, there are several rooms that may have been used for storage.

The southeastern sector is the largest of the three and consists of several abutting buildings and an ushnu (altar) in the form of a platform that allows a good view of the valley. The two largest buildings in this complex are actually courtyards surrounded by various rooms. The entire sector is enclosed by a high adobe wall.

The northern sector is a large rectangular building with a single entrance and a central patio surrounded by a maze of small rooms. This building, which is 100m wide and 150m long, stands in a fold of the terrain to the north of the Inca road. It is flanked with two smaller multi-room buildings. At one time, the entire complex was decorated with red, yellow, and white stucco, which can still be seen in patches today.

The road on either side of the plaza was easily defended as it passed between the buildings of the northern and the southeastern sectors. The large plaza probably served as an assembly point for the Incas’ armies and as a ceremonial area where the soldiers performed their war dances before they sallied forth to wage war on their enemies (Kauffmann-Doig, 1980).

Paramonga

The “fortress” of Paramonga is located to the north of Lima, on the old coastal road of the Incas, near the settlement of Pativilca. It stands on the banks of the Fortaleza River, less than 1km from the Pacific Ocean. Built between 1200 and 1400 CE, it was an important outpost and worship center on the southern border of the Chimú kingdom. Like most of the fortification of the Andean region, it probably combined administrative, religious, and military functions. In its heyday, it dominated the town, the river, the road, and the fields around it. It was conquered and integrated into the Inca defensive system by Pachacutec, who brought the Chimú kingdom to its knees.

Paramonga is made entirely of adobe and adobe bricks and consists of terraces built around the contours of a hill to form a rough pentagon. Although Hernán Cortés reported seeing five walls in 1532, Paramonga actually consists of four terraces. The administrative and religious buildings stand on the last terrace, surrounded by their own wall, which might have given Pizarro the impression that there were five walls. At the corners of Paramonga, four trapezoidal structures give the complex the appearance of a European bastioned fortification. Seen from the sky, the complex looks like a stylized flame, probably an effect deliberately sought. According to the early Spanish chroniclers, the walls of Paramonga were entirely plastered with brightly colored stucco, lavishly decorated with animal and bird motifs. Today, the plaster is all but gone and large sections of the adobe terraces are crumbling away. Even so, this fortress is still the best-preserved construction in the area.

Paramonga is a fairly typical pre-Colombian fortification of the Peruvian coast. It is reported that a similar administrative-religious-military structure stands at Tumbes, where Francisco Pizarro and his small force first set foot in Tawantinsuyu.

The Quito fortress area in Ecuador was probably the last that the Incas erected and can be mostly attributed to Tupa Inca, the son of Pachacutec, and to his heir, Huayna Capac.

One of the largest pukaras in the area was Quitoloma. It stood on a hill overlooking the city of Quito, and could be considered one of the most classical representatives of Inca military architecture. It consisted of three spiralling rings of defensive terraces accessed through gates defended by chicanes and square towers. At its top, stood an ushnu, warehouses, and living quarters. It is thought to have been the headquarters of the system of fortifications in the area of Quito because it was not only one of the largest forts, but it also appears to have held an extensive administrative center and large storehouses (Fresco, 2005).

One of the largest groups of pukaras in this area was the Pambamarca group, which occupied a ridge of the same name that ran from north to south. It guarded the approaches to Quito and included, among others, the forts of Jambimacbi, Pambamarca, Paccha, Campana, Oljan Tablarumi, Acbupallas, Guachalá, and Bravo.

Antonio Fresco has also identified east-west lines of fortifications at the confluence of the Guayllabamba and Pisque rivers – formed by the pukaras of Lulumbamba, Guayllamba, and Pambamarca – and near Lake Yaguarcocha, whose forts were strung up between Aloburo and extended between the ridges of Yanaurco and Cotacachi. It is likely that these lines of outposts were built successively to secure the territories of the Incas as they expanded ever northward (Fresco, 2005).

Machu Picchu

Like most Inca outposts, Machu Picchu was an administrative, religious, and military complex. Although it is widely thought that it was built after the Spanish conquest of the Inca empire, archaeologists now believe that it had been mostly abandoned by the time Pizarro arrived. It probably served as an outpost to subjugate the tribes of the Vilcabamba region. When the Incas had to evacuate Cuzco, they sheltered the Virgins of the Sun here. The Spanish never discovered Machu Picchu, and, after the last of the Virgins died, it was swallowed by the jungle and was not rediscovered until 1911 by the American explorer Bingham.