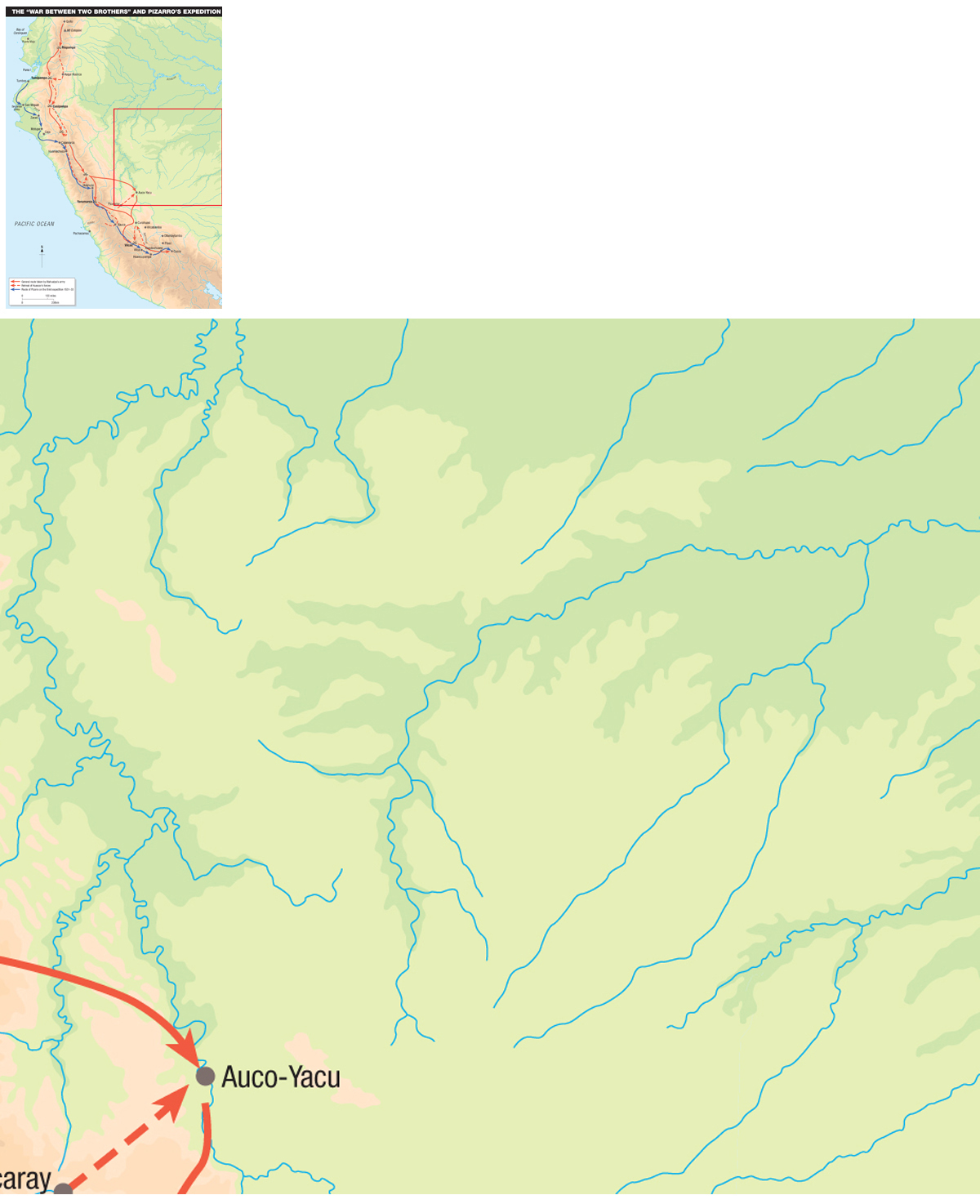

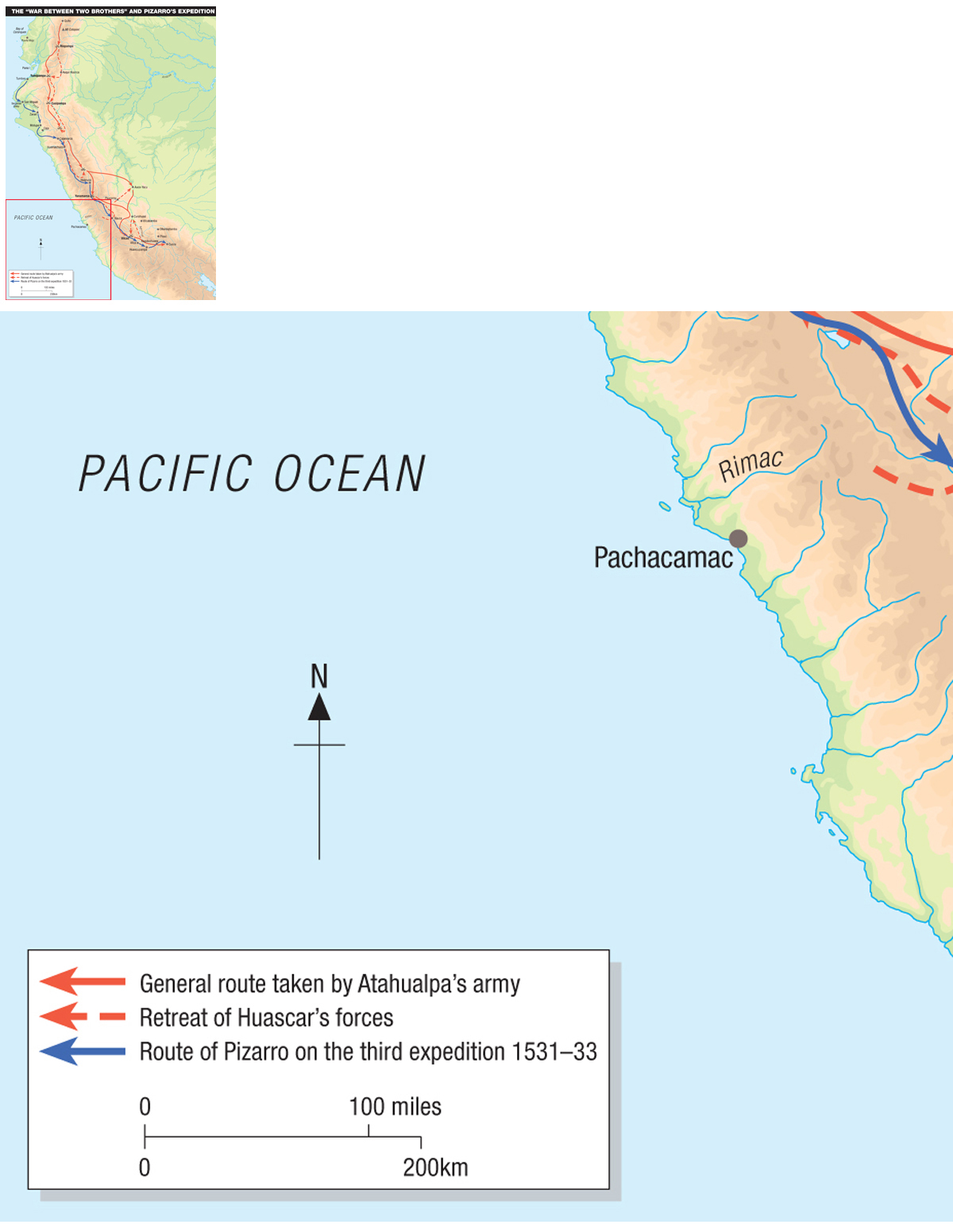

Francisco Pizarro, a conquistador from the poor region of Extremadura in Spain, went to the Americas to seek fame and wealth and to spread the “true faith.” He was with Balboa in 1513 when Hernán Cortés brought the Aztec empire in Mexico under the banner of Spain. Inspired by Cortés, he decided to mount his own expedition along the west coast of South America in 1524, but the rabble he took with him was easily beaten back in coastal Colombia. However, his 1526 expedition laid the groundwork for his discovery and conquest of the Inca empire. His lust for conquest was spurred on when one of his captains ran across a raft carrying Incas with their treasure near the Equator.

Pizarro disembarked at the town of Tumbes on the south side of the Gulf of Guayaquil, which later served as his gateway to the Inca empire. He sent Alfonso Molina to visit the city and Alfonso returned with extravagant stories of riches and impregnable fortifications with eight walls. However, questioning Molina’s reliability, he sent Pedro de Candia to verify his claims.

De Candia suited up in full armor, strapped on his sword, and carried his harquebus, which the Indians had heard being fired on one of the ships. After he fired his weapon, the locals, suitably awed, took him on a tour of the city and its defenses. De Candia gave Pizarro a more realistic account of the wealth and defenses of Tumbes: the city only had a triple row of walls and a strong garrison (Betanzos, 1984; Cieza de León, 2001). Built by Tupa Inca, this pukara was one of most important coastal fortifications in the northern part of the empire. With fewer than two dozen men, Pizarro did not attempt to overwhelm its large garrison or even storm the powerful fortress.

Encouraged, but too weak to strike, Pizarro sailed south, past the great coastal desert of northern Peru, to the mouth of the Santa River. Here, he learned of a city of gold and silver located in the mountains beyond the coast that was the capital of the worshipers of the sun. He then turned back for Panama, knowing that beyond the Inca city of Tumbes lay an empire with untold riches.

In 1531, Pizarro embarked a large expeditionary force in Panama of 180 men and 36 horses (from Spain) on three ships for the journey south. After he landed at San Mateo Bay in the province of Coaque, north of Tumbes, he moved inland, struck at a small town, and plundered its gold and silver, rousing the locals’ wrath in the process. He then headed for Tumbes overland, following the coast. His reputation must have preceded him, for all the villages in his path had been deserted. Pizarro’s little band reached the Gulf of Guyaquil in April 1532 (Cieza de León, 2001).

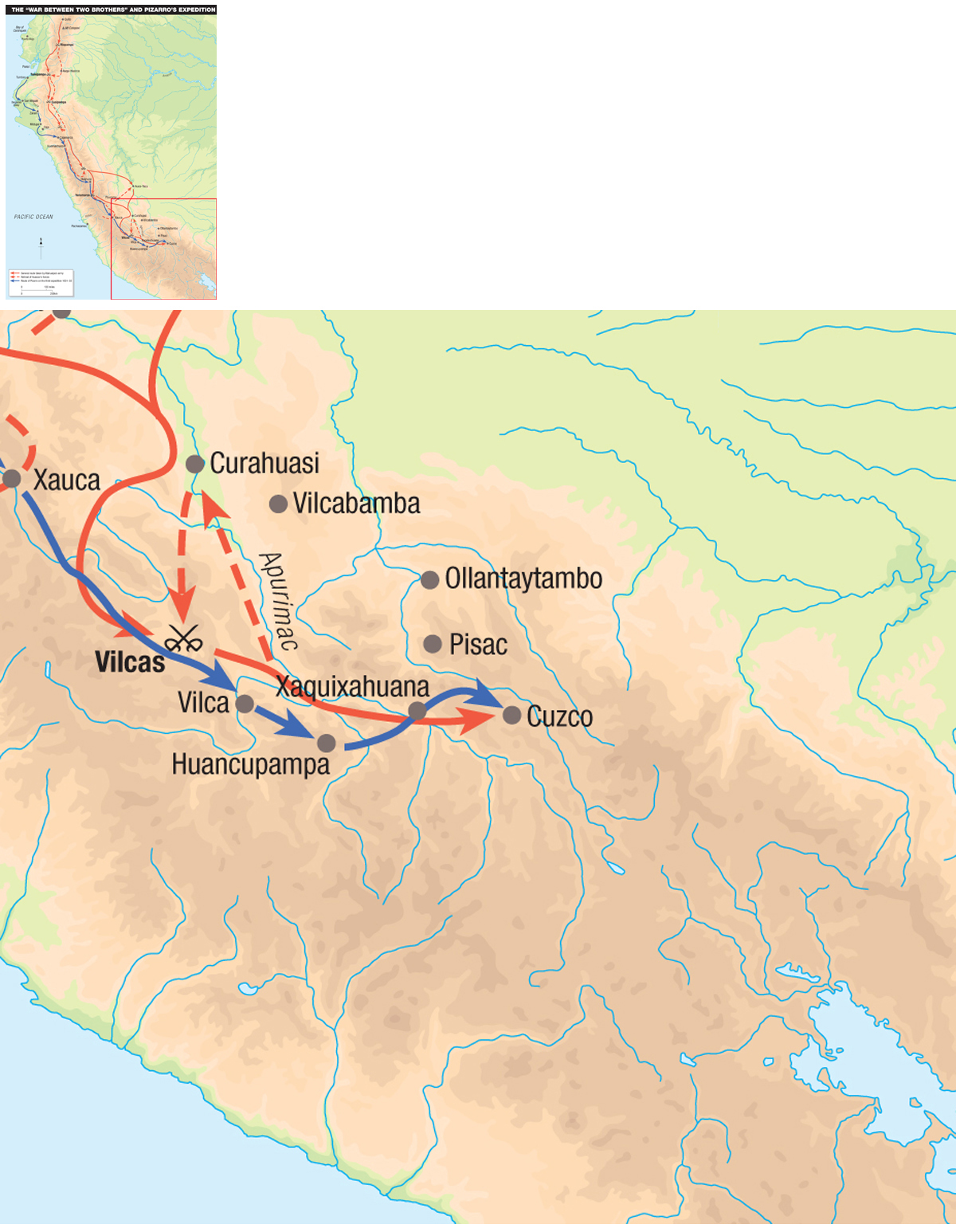

Atahualpa had informed the chiefs of the province not to confront the Spaniards directly and to pretend friendliness, but eliminate those that strayed from the main body (Cieza de León: 117, 2001). At the time, unbeknown to Pizarro, the great civil war between Atahualpa and his half-brother Huascar was in full swing.

Pizarro’s force landed on the island of Puna, whose inhabitants, enemies of Tumbes, welcomed them with open arms. Soon, however, the islanders became disenchanted with their guests. Thousands of warriors assaulted Pizarro’s force on three sides. The Spaniards created a shield wall from which they struck down the assaulting warriors with sword and pike while their cavalry stood by in support. This time, Pizarro’s force consisted of seasoned soldiers well able to take on the enemy. The pike men, harquebusiers, and swordsmen organized in formation easily repelled the enemy while suffering fewer than five dead.

Reinforcements arrived from Nicaragua under the command of Hernando de Soto, possibly another hundred men. Although there is no general agreement on the subject, the expedition included either two or four small cannons known as falconets weighing about 500 lb. each, which were light enough to be transportable in the rough terrain of the Andes.

Once more, Pizarro crossed over to Tumbes, but the wealth he sought there was largely gone. The fortress remained, but the Inca troops had withdrawn to take part in the civil war that raged across the empire. In May 1532, Pizarro set out on his march of conquest, leaving a garrison of 25 men at Tumbes.

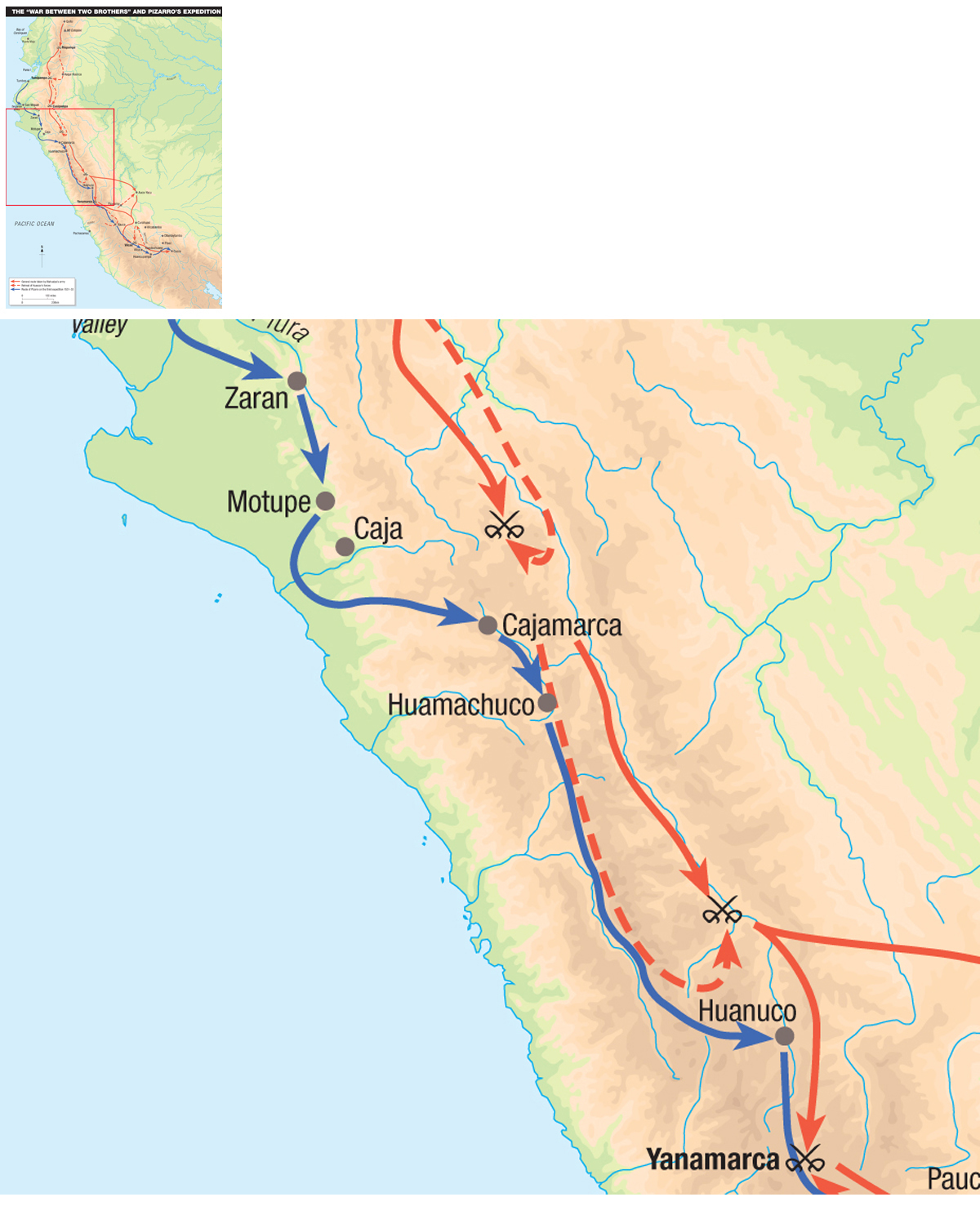

On the Chira River, Pizarro founded the town of San Miguel, a typical colonial town surrounded with fortifications, which served as his inland base. On September 24, 1532 Pizarro began his march into the Andes with 177 men, including 65 cavalry. The company included only three harquebusiers and possibly 20 crossbowmen. As they moved up to the Andes, heading towards Cajas, the Spaniards acquired Indian allies to augment their numbers. Their artillery consisted of three harquebusses and possibly two small cannons. Fortunately, the villages en route were devoid of Inca garrisons, which had been called to join in the civil war. Thus, the Spanish force was spared the task of overcoming any fortified town. As Hernando de Soto scouted ahead through the valley, he found a formidable fortress built entirely of cut stone at Huancabamba. From this point on the fortresses were no longer made of sundried bricks. Huancabamba (which means “valley of the stone spirit guardians”) stood at a crossroads of the main Inca road that led from Santiago (in Chile) to Quito (in Ecuador). De Soto followed the road from Zaran to Huancabamba and to Cajas, a day away. The east-west highway continued on to Jaen in the Amazon region, home of the head-hunting Aguaruna Indians.

In the meantime, Pizarro and 170 men slowly ascended the Andes following the Zana River and crossed the steep and narrow Nancho Gorge where they found a stronghold located on a pass at 12,000ft above sea level. At this point, the Spaniards and their horses must have been struggling to acclimatize to such high altitudes. The Incas, who were well adapted to this environment, chewed on coca leaves to function more effectively. At these heights, the more nimble native warriors would have probably wiped out Pizarro’s men. Fortunately for the Spaniards, there were no defenders, the fortress was abandoned, and the road to Cajamarca was open. The descent to the east brought some relief to the European adventurers, especially those suffering from altitude sickness.

Atahualpa, the victor of the recent civil war, was camped at Cajamarca with his army. He sent a gift-bearing emissary, whose likely mission was also to spy on the Spaniards. He was well aware of the strength of the Spaniards. His first informers had apprised him of the number of bearded strangers who claimed to be viracochas (gods) and carried “silver wands” (steel swords). However, Atahualpa quickly deduced that these strangers were mere mortals and concluded that the silver wands could not inflict much damage. Atahualpa also learned from his spies that the bearded strangers were accompanied by creatures larger than llamas that were part men and part animal and wielded devastating power. However, he was told, in the evening the two components separated, becoming men and beasts.

As Pizarro and his men marched on Cajamarca, Atahualpa did not attempt to stop him, defend his fortified towns, or use any of the defensive positions on the roads leading into the heart of his empire. His army, which numbered tens of thousands of men, quietly awaited his orders.

As he approached Cajamarca, a city of 7,000 to 10,000 inhabitants, Pizarro formed his troops into three small units and readied to fight, but encountered no resistance. On November 15, 1532 he entered the eerily deserted and silent city. At the end of the main plaza of Cajamarca, there was a stone temple on a platform, which the Spaniards took to be a fortified position. In addition, a three-tiered pukara overlooked the city from its perch on a commanding height.

Realizing that the 80,000-strong Inca army could easily overrun his puny force, Pizarro decided to bluff his opponent. Rather then meet his opponents in the open field, he carefully evaluated the defences of Cajamarca in order to take full advantage of them. Meanwhile, he sent de Soto, his brother Hernando, and 35 horsemen to Atahualpa’s camp. The Inca’s camp was located in a defensive position formed by a small winding stream. It was accessed by means of a wooden bridge guarded by a large contingent. De Soto’s cavalry splashed through the shallow stream, bypassing the guard unit, and rode into the camp. Once he found himself face to face with the Inca, de Soto, instead of dismounting and paying his respects to the monarch, pranced his horse almost on top of the sitting Atahualpa. The Inca watched impassively, while some of his entourage flinched and drew back. Through an interpreter, de Soto invited Atahualpa to visit Pizarro at Cajamarca. After the Spaniards left, the Inca ordered everyone executed who had flinched before the Spanish horses (Betanzos, 1996).

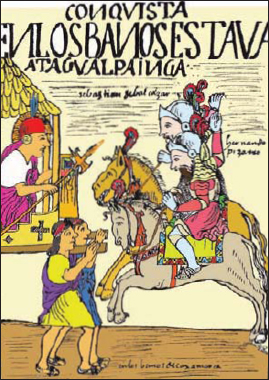

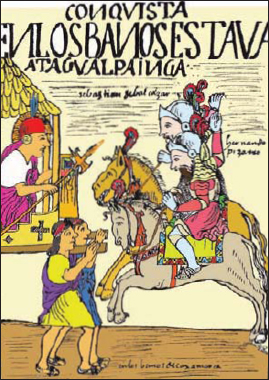

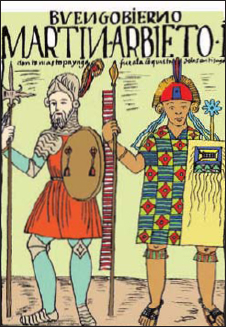

An engraving by Guamán Poma de Ayala showing Hernando Pizarro and Sebastian Benalcazar meeting Atahualpa.

The irony of Pizarro’s situation was that he had led his little band into the great Inca fortress area in the Andes without encountering much resistance, and now found himself outnumbered, with no direction in which to turn for safety. The possibility of retreat was nil and his only option was to capture the Inca leader. To do this he turned Cajamarca into his own fortified position and prepared to defend the town with guards stationed at all the approaches and on the pukara above to watch for the advance of the Incas. William Prescott describes the situation:

On November 16, the scene was set. Pizarro would either take the Inca leader or face certain destruction. Since his small force could not easily defend Cajamarca, he decided to overwhelm his guests inside the town. The plaza … was defended on three sides by low ranges of buildings, consisting of spacious halls with wide doors … opening into the square. In these halls, he stationed his cavalry in two divisions … The infantry he placed in another of the buildings, reserving 20 chosen men to act with himself as occasion might require. [Prescott, 1847: 935]

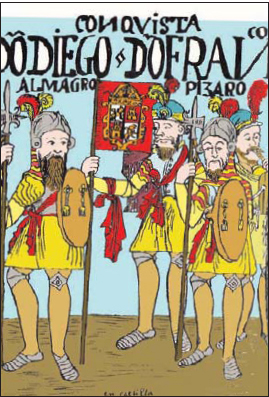

An engraving by Guamán Poma de Ayala showing the conquistadors Diego Almagro and Francisco Pizarro.

The Inca arrived with his large armed procession, but stopped and began setting up camp outside the city. Pizarro and his men, anxiously waiting to spring the trap from inside their fortified position, were under heavy strain, especially when they saw the sizable Inca force now encamped in front of them. It was late in the day and Pizarro tried to coax Atahualpa into the city. Surprisingly, the Inca consented, and moved into Cajamarca with his entourage, unarmed. Atahualpa may have been playing a psychological game of his own, relying on the fact the Pizarro was vastly outnumbered in the heart of his empire. As the Inca and his escort entered the town, they found the streets and plaza deserted, with no sign of the Spaniards. Suddenly, a friar emerged from the shadowed doorway, approached him, and tried to convert him to Christianity. As Atahualpa recoiled, Pizarro gave his signal. The falconets boomed and the cavalry of Hernando Pizarro and de Soto burst into the plaza hacking and slicing away. Many Indians were felled and Atahualpa was eventually thrown from his richly decorated litter and seized by Pizarro. The only Spanish casualty was Francisco Pizarro, who was wounded during the massacre. The Inca army dared not attack while its leader was in Pizarro’s clutches. In exchange for his freedom, Atahualpa promised his captor two roomfuls of gold and silver. Precious statuettes and vessels flowed in for weeks from all corners of the empire.

However, Pizarro remained in a vulnerable position until Diego de Almagro arrived at San Miguel with 150 soldiers, including 84 cavalry, in December 1532. Almagro joined Pizarro sometime between February and April 1533. Meanwhile, he garnered the support of tribes that held grudges against the Incas and Atahualpa.

Pizarro ordered Atahualpa’s execution in July 1533, after which he continued his advance upon Cuzco and his search for wealth. He entered Cuzco on November 15, 1533, one year after arriving in Cajamarca. After unsuccessfully trying to set up a puppet Inca ruler, Pizarro installed Manco Inca, son of Huayna Capac and half-brother of Atahualpa and Huascar, early in 1534. In the meantime, Sebastian Benalcazar, another of Pizarro’s captains, marched along the Inca Altiplano highway with 140 men and Indian auxiliaries and entered Quito. Pizarro now dominated all the major centers of the Inca empire.

The Spanish conquistadors strove to repress the natives’ religious practices with such ruthlessness that Manco Inca and his followers rebelled against them. In February 1536, thousands of warriors put the Spaniards in Cuzco under siege. A small Spanish garrison stationed at Sacsayhuamán withdrew into the city of Cuzco, allowing Manco Inca’s forces to occupy the pukara. Manco Inca waited to concentrate his forces before launching a major assault on Cuzco. Since the Spanish cavalry was less effective on sloping ground, he launched an assault from the vicinity of the fortress. The Indian warriors hurled missiles down the hill onto the city of Cuzco. The Inca artillery consisted mainly of fire arrows, red-hot stones wrapped in cotton, and balls of some bituminous substance. The warriors used slings to hurl their projectiles onto the thatch roofs of the city’s buildings. Before long, they had set almost the entire city in flames. Cuzco burned for more than a day. By this time, the Inca’s warriors had learned how to tackle horsemen. In order to prevent cavalry sorties, they barricaded streets and even dug pits, some with stakes. During the weeks of fighting, the Inca forces took a key bastion of the city walls and held it with their slingers, who pinned down the Spanish. Before long, the Spanish only held the area around the main square. Although they were unable to prevent the destruction, the 190 Spaniards of the garrison and their Indian allies finally managed to repel Manco Inca’s force, which probably consisted of over 40,000 men.

Hernando Pizarro, realizing that he needed to retake the Sacsayhuamán fortress above the city, ordered his young brother Juan to take 50 horsemen, break out of the city, maneuver around the enemy, and assault the fortress. To carry out this plan, the Spaniards first had to neutralize the obstacles that blocked their path. To cover Juan Pizarro’s sortie, another smaller group of cavalry diverted the besiegers’ attention in another direction. Juan Pizarro’s force found the passes leading up to the fortress undefended and reached the outer wall without alerting the enemy inside. Under cover of darkness, the Spaniards removed the large stones that blocked the entrance to the stronghold and took the defenders by surprise, aided by the fact that there were no guards. Juan Pizarro and his men rode through the opened gateway of the outer wall and moved toward the second parapet. Soon, the space between the walls swarmed with Inca soldiers hurling missiles at them. Juan Pizarro led the assault, but a jaw wound he had sustained during a previous engagement prevented him from wearing a helmet. Some of the Spaniards were felled despite their armor, but others poured through the breach in the defenses. William Prescott describes what happened next:

The garrison in the fortress hurled down fragments of rock and timber on their heads. Juan Pizarro, still among the foremost, sprang forward on the terrace, cheering on his men by his voice and example; but at this moment he was struck by a large stone on the head, not then protected by his buckler. The dauntless chief still continued to animate his followers by voice, till the terrace was carried, and its miserable defenders were put to the sword. [Prescott, 1847: 1027]

Juan Pizarro died soon after. The next day, as the battle continued to rage, Hernando Pizarro dispatched his last dozen horsemen to reinforce the attack when Manco sent in 5,000 additional warriors. Hernando joined the fray with some foot soldiers and Indian allies as the Spaniards were preparing to take the fortress by escalade. Using scaling ladders, they drove the Inca soldiers from the last walled terrace of the fortress and into the three great towers, one of which was over five stories high, and the remaining buildings. Some of the fiercest fighting of the campaign took place within the fortress. Pizarro ordered a simultaneous assault by escalade on all three towers. They finally overcame the Inca force, slaughtering 1,500 of them in the fortress.

Pizarro left a garrison of 50 Spanish foot soldiers and some Indian allies. Although the Incas tried to retake the fortress, the battle turned against them. By the end of May, even though the siege continued, the position was secure, the situation in Cuzco had improved, and Manco’s troops were driven back (Hemming, 1970: 197–203).

Francisco Pizarro, who was in the new city and capital of Lima, learned of the desperate situation in Cuczo in May and sent a relief force. However, mercilessly pelted with boulders on the mountain roads and in narrow defiles, this Spanish contingent was unable to reach Cuzco. Hernando Pizarro, still under siege, managed to sneak out a force of 80 horsemen, 30 foot soldiers, and an unknown number of Indian allies to strike Manco Inca at Ollantaytambo. He took a less used route to approach the town, hoping to take the Inca by surprise only to find that side of Ollantaytambo much more imposing than he had expected:

The palace, or rather fortress, of the Incas stood on a lofty eminence, the steep sides of which, on the quarter where the Spaniards approaches were cut into terraces, defended by strong walls of stone and sunburnt brick. The place was impregnable on this side. On the opposite, it looked towards the Yucay, and the ground descended by a gradual declivity towards the plain through which rolled its deep but narrow current. This was the quarter on which to make the assault.

Crossing the stream without much difficulty, the Spanish commander advanced up the smooth glacis with as little noise as possible. The morning light had hardly broken on the mountains; and Pizarro, as he drew near the outer defences, which as in the fortress of Cuzco, consisted of a stone parapet of great strength drawn around the enclosure, moved quickly forward, confident that the garrison were still buried in sleep … a multitude of dark forms suddenly rose above the rampart … [and] at the same moment the air was darkened with innumerable missiles, stones, javelins, and arrows which fell like a hurricane on the troops. [Prescott, 1847: 1031–32]

Large numbers of slingers and bowmen from the Amazon defended the fortified complex. Twice Pizarro’s horsemen tried to regroup and assault the walls, but they were driven away. Next, Pizarro sent an infantry force against the fortress, but had to withdraw under a hail of stones and arrows. Manco Inca had flooded the plain, severely limiting the movements of the Spanish cavalry in the muddy ground. Pizarro had no choice but to break off the engagement and retreat. Despite this victory for Manco Inca, his long siege of Cuzco faltered and his chances of success evaporated when Pizarro was able to raid the region for food for the defenders (Hemming, 1970: 213–15). The facts, as related by Juan de Betanzos (1996), seem to indicate that Manco tried to destroy all the towns and stores in the area.

The statue of Francisco Pizarro in the Peruvian capital Lima.

Manco Inca sent one of his generals who had successfully fought the Spanish in the Andes to assault Lima on the coast. Although the city was not heavily fortified, the siege failed because the Spanish cavalry was easily able to break up the assault on the level ground surrounding the city. Finally, after six months, the Indians abandoned the siege. The revolt began to falter even though much of the country still had to be pacified. Finally, reinforcements arrived from Spain and Almagro’s expedition returned from Chile (the revolt began when Almagro departed for Chile, leaving a smaller Spanish force in Peru). In November 1536, Alfonso de Alvarado left Lima at the head of 210 infantrymen, 100 cavalry, and 40 crossbowmen. He engaged the enemy in the hinterland and waited for 200 more reinforcements. Thus, with two relief forces coming from two directions, the siege of Cuzco was about to end.

Almagro, who had other ambitions, tried to enlist Manco Inca’s cooperation. Instead, the Inca launched an attack with 15,000 of his followers, and was defeated. The Spanish were now too strong to be overcome, so Manco withdrew from his fortress of Ollantaytambo into the mountain fastness of Vilacamba where the dense vegetation was less inviting to the Spaniards. Still, a Spanish force pursued him relentlessly. The Inca ordered the destruction of the road leading through the Urubamba Valley and the great suspension bridge at Chuquichaca. Undeterred, the Spaniards followed him to the town of Vitcos, which they plundered. Once again, Manco Inca escaped their clutches and headed further into the wilderness. It was reported that he established a new city of Vilcabamba in this remote region from which he continued to rule his small kingdom for several years. He was treacherously assassinated by several Spaniards who pretended to be fleeing from Pizarro’s wrath after Almagro’s rebellion.

An engraving by Guamán Poma de Ayala.

Manco had used the Vilcabamba Valley and the surrounding jungle-shrouded mountain range as a defense against further Spanish incursions. The site of his capital of Vilcabamba has not been identified positively, but recently uncovered cities in the area are good candidates. The explorer Hiram Bingham believed it was Machu Picchu, which he discovered in 1911. However, even though this city is located in a remote site and it overlooks the Urubamba River between Ollantaytambo and the Chuquichaca bridge, it is unlikely to have been Manco Inca’s refuge – especially since it had probably been abandoned by the time Manco Inca withdrew into the jungle fastness. In the mid-1960s, explorer Gene Savoy, after closely examining the site of Espíritu Pampa in the Vilcabamba region, concluded that this must have been the Inca’s last refuge. However, during the last decade other possible sites have also been identified as the lost capital.

Juan Pizarro’s assault on Sacsayhuamán

Juan Pizarro was the half-brother of Francisco and Hernando Pizarro. When Francisco Pizarro left to explore the northwest coast of Peru he left Juan and Hernándo in charge of Cuzco, which they ruled with a rod of iron. In May 1536 Manco Inca led an uprising to overthrow Spanish rule in Cuzco, which led to numerous battles for control of the city and the Inca-held pukara of Sacsayhuamán. Juan tried to break the siege of Cuzco by leading an attack on Sacsayhuamán, but he was struck on the head by a stone hurled by an Inca warrior during the assault, and later died of his injuries. The Spanish eventually gained control of the fortress the next day, defeating Manco Inca’s force, and lifting the siege.

Manco Inca’s great rebellion failed because he was unable to drive the Spanish from fortified positions. However, if the Incas had put up a similar resistance a few years earlier, when Pizarro had first ventured into their lands, they surely would have defeated him.

In 1569 Tupac Amaru succeeded Manco Inca, and revolted against the Spanish in 1572. The Viceroy dispatched an expedition of 250 Spaniards and 2,000 Indian warriors to put an end to the last Inca stronghold in the valley of Vilcabamba. Tupac Amaru was betrayed by local tribesmen who warned the Spaniards of the ambushes the Inca had prepared for them along the road and mountain passes. The Spaniards rebuilt the key bridge at Chiquichaca and entered the valley, passing through dense jungle to descend into the valley. Here, Tupac Amaru’s troops burst upon the Spanish, who were strung out in single file, and engaged them in close hand-to-hand combat. After taking losses, the Spaniards drove them off and advanced to Vitcos. Tupac Amaru’s troops continued to withdraw through the jungle toward the city of Vilcabamba, with the Spanish in hot pursuit. A deserter warned the Spaniards that the fort of Huayna Pucara would bar their path. The Incas had prepared defensive positions along the narrow defiles that ran for about three miles before the fort using boulders and rocks. The fort overlooked the exit. Just in front of the fort, they planted numerous palm stakes covered with poisonous liquids, leaving only enough space for single-file progress up to the fort. As at Thermopylae in Greece over 1,500 years before, a traitor caused the downfall of the stronghold. An Indian showed the Spanish force how to scale the heights, and they took the positions where the boulder drops were planned. Next, he led them to a position dominating the fort. The small Spanish artillery pieces finally forced the Incas to retire from it. The Spaniards were able to secure the Vilcabamba region on June 24, 1572, eliminating the last known stronghold of the Incas – but there was no gold or food to reward them. Tupac Amaru escaped, but a small party pursued him into the jungle for more than a hundred miles before capturing him. Thus, the last remnants of Tawantinsuyu were finally overcome.

In November 1780, José Gabriel Condorcanqui, who called himself Tupac Amaru II and claimed to be the legitimate descendant of Tupac Amaru, led another rebellion against the Spaniards. This was the last major revolt to threaten Spanish control of the viceroyalty of Peru. At the head of 6,000 Indians and mestizos (those of mixed European and Indian ancestry), he defeated the first major Spanish force he encountered and captured two cannons and several hundred muskets. During the next month, after his force had swelled to 60,000 men and he had acquired 20 cannons, he turned his attention to Cuzco. Only one day before he reached Cuzco, the garrison of the city received a reinforcement of 200 men from Lima. The rebel leader occupied Sacsayhuamán, but, his cannons notwithstanding, he gained no great advantage over the Spaniards in Cuzco. In January, Tupac Amaru launched two attacks against the city, but failed both times. On January 23, 1781 a relief force ended the siege for good. By April, the rebellion was broken and the old Inca fortresses never served again (Romero, 2003: 20–26).