Introduction

When I was a kid and fears of death came to me in the night, I’d wake up my mom and she would console me.

Am I going to die?

Yes, but not for a long, long, long time.

Are you going to die?

Yes, but not for a long, long time.

As I got older, death entered our casual family discourse. Over dinner, we would engage in the burial-vs.-cremation debate, or my mom would issue one of her decrees: “If I ever become a drooling mess, just shoot me.” As with most things, joking about death was our way of acknowledging its inevitable presence. We spoke about it in the light of day so that when we faced it later, alone, it wouldn’t be so scary.

One night, when I was twenty-two or twenty-three, I couldn’t sleep: That recurrent and agonizing prospect of losing my mom slipped in again. This time I decided not to push the thoughts away. I allowed myself to vividly imagine my mom’s death, to feel the pain of the moment I learned she was gone.

With sleep an ever-more-distant prospect, I went even further: I imagined the next day, and the day after that. The earth would continue to spin, and I’d be left in a world without her. My map would be gone. The ground beneath my feet would be gone.

Who could I call to ask how to cook a potato? Who would listen to me talk about my work for more than five minutes? Who would tell me everything? Who would forgive me for everything? How could I possibly navigate this world without the person who brought me into it?

I cried. Then I had an idea. The next morning, while we made breakfast, I asked my mom to write a book of step-by-step, day-by-day instructions I could follow after her death.

She laughed. Then she said yes.

Hallie Bateman

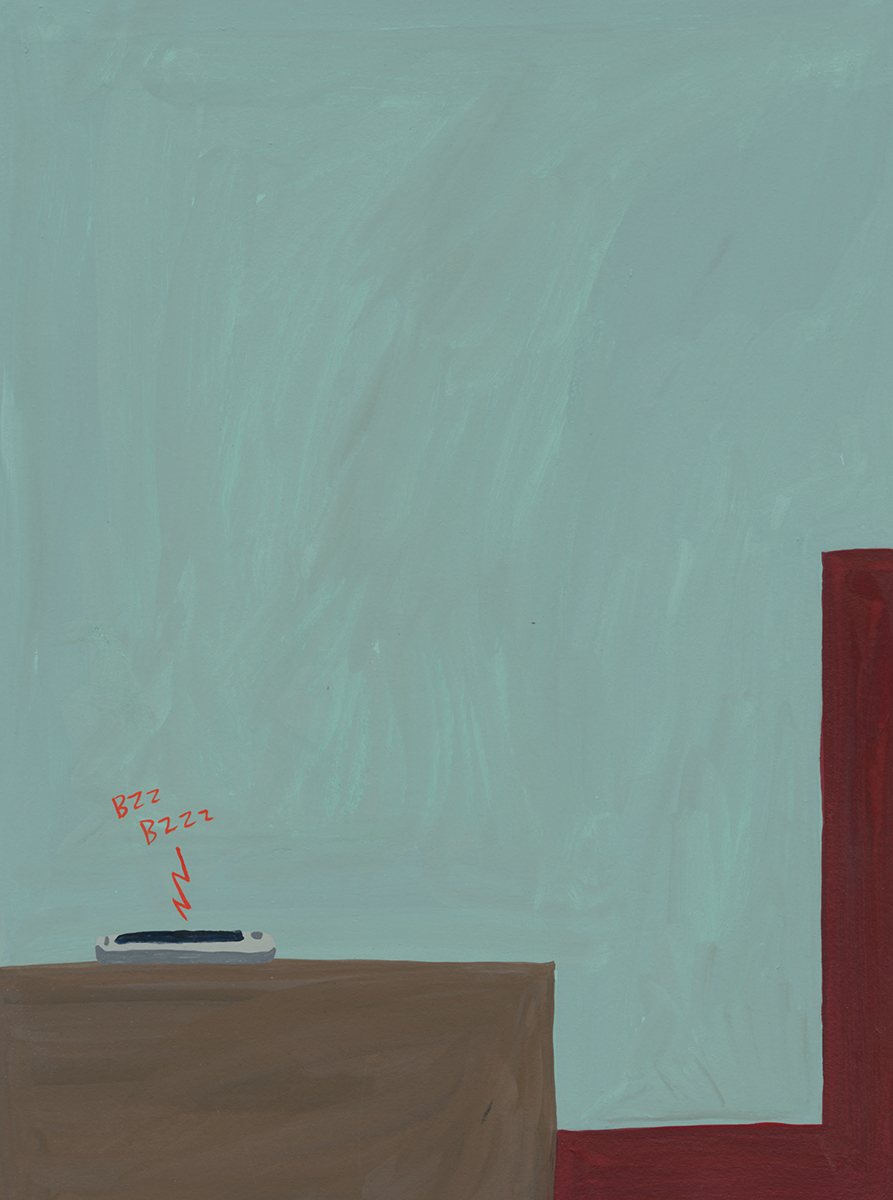

This could go on for days. Step away from the phone.