OTHER CHALKLANDS SOUTH OF THE THAMES

![]()

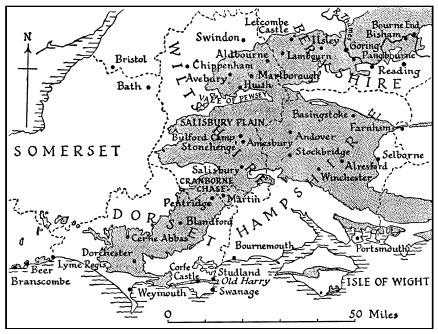

THE LARGEST stretch of real chalk downland in Britain is the central area which includes Salisbury Plain. It forms the left-hand bottom loop of the “£” symbol which represents chalk on the geological map, and extends continuously for a distance of as much as fifty-five miles from east to west. In addition to Salisbury Plain it includes a great part of Hampshire, the North Wiltshire and Berkshire Downs, and much of Dorset. There are outliers in Devon. Unfortunately the chalk flora is, on the whole, less interesting than that of the North and South Downs and Isle of Wight discussed in the last two chapters. From the botanist’s point of view, a great deal of the country is too uniform to be exciting.

The characteristic feature of this part of England is the use of the downs ever since prehistoric times as pasture for sheep. The modern flocks are almost trivial compared with those maintained in the past, whose influence has moulded the vegetation as we know it to-day. Sheep are very close-grazing animals, “living lawn-mowers” as H. J. Massingham has called them, and only a limited number of grasses and flowers are able to exist under their constant nibbling. Those that do are the species characteristic of short, dense turf of the kind which still covers countless acres of Wiltshire, Hampshire, Berkshire and Dorset downland. Long treeless miles of uniform flora are characteristic of such country with only occasional areas where the wild flowers are more varied.

NORTH HAMPSHIRE

The eastern part of Hampshire has many well-wooded areas. The flowers of Selborne Hanger are representative of many beechwoods in the district. In some woods and copses the Narrow-leaved Helleborine, Cephalanthera longifolia (Plate 22), is locally plentiful. Round Winchester there is more varied country. For example, on one hill there is an abundance of orchids, including the Spotted, Dactylorhiza maculata, Sweet-scented, Gymnadenia conopsea, Pyramidal, Anacamptis pyramidalis, Bee, Ophrys apifera, Marsh, Dactylorhiza praetermissa, Frog, Coeloglossum viride, Lesser Butterfly, Platanthera bifolia, and very locally the Man, Aceras anthropophorum. The Marsh Orchids which grow here are short, dumpy forms very different from those of wet marshes. North of Winchester, Field Eryngo, Eryngium campestre (Plate 16), is to be found. The main locality was ploughed up during the war but the species still persists nearby. In another place Cut-leaved Germander, Teucrium botrys, occurs in great quantity on spoil-heaps by the railway. Both these plants are under suspicion of having been introduced to these places by human activities. There is one chalky arable field where Pheasant’s Eye, Adonis annua, and the curious Round-leaved Hare’s-ear, Bupleurum rotundifolium, are always to be found when the condition of the crop permits. This district includes the most easterly station known to me for Yellow Star-of-Bethlehem, Gagea lutea, but although there are thousands of plants in the copse, only a very few of them produce flowers.

SALISBURY PLAIN

Towards the western side of Hampshire the country is less wooded. Immediately across the Wiltshire boundary is the great, open, undulating sheep-moulded Salisbury Plain. Except in the valleys, the scenery is varied only by occasional earthworks and a few clumps of planted trees. Apart from these, it is mostly continuous close pasture with a very uniform flora. Large areas have been taken over by the military, whose activities restrict, or even prohibit, public access, but generally serve to protect, rather than destroy, the wild flowers. Some of the best plants grow on War Office land. For example, Purple Milk-vetch, Astragalus danicus, and Cut-leaved Self-heal, Prunella laciniata, grow on downs where access is only possible at certain times. The activities of the Army have had an interesting influence on the plant-life of this region.

They have led to the introduction of alienspecies round the great camps, to the breaking up of downland turf by the tracks of the tanks, and sometimes to the increase of flowers, owing to the exclusion of the public and grazing animals. The construction of a new road at Bulford Camp in 1939 brought up the buried seeds of Pheasant’s Eye and the scarlet flowers appeared in thousands on the chalk rubble at the side. Now the ground has become grassed over and I believe they have disappeared.

The two botanical features of Salisbury Plain of greatest interest are the abundance of both Tall Broomrape, Orobanche elatior, and Dwarf Sedge, Carex humilis. The former is a parasite on Greater Knapweed, Centaurea scabiosa, and is found in greater plenty here than in any other part of Britain. In July and August the brown, dried spikes of the plant in fruit line many of the roads across the plain like two-feet high sentries. They are conspicuous enough from a fast-moving car, but the Dwarf Sedge is usually only seen after a hands-and-knees search. Actually the practised eye can pick it out from a little distance by the rather pale yellow hue of its wiry foliage, but this requires experience. It covers quite a lot of ground on the Plain and is found particularly on well-drained hilltops and earthworks. The flowers appear in March and April, and are followed by small fruiting spikes hidden amongst the leaves. I have seen these as late as August, but usually they have dropped by then.

One day in 1947 included the achievement of a botanical ambition which I had long cherished. With the help of my Wiltshire friend, Mr. J. D. Grose, I saw the Tuberous Thistle, Cirsium tuberosum, in the place where it was first found in Britain. The story is a remarkable one. It was in 1812 that A. B. Lambert, one of the first Vice-Presidents of the Linnean Society, made the discovery. A few years later he showed the plant to his friends, Sir J. E. Smith and the Dean of Carlisle (later Bishop Goodenough), but, unlike most rarities, the knowledge of its exact locality was not passed on to future generations of botanists. It seems that the Tuberous Thistle was collected here again in 1830, 1849, 1881 and 1888, but these finds were not generally known. In fact, the locality found by Professor Buckman in 1857, 25 miles to the north-east, remained the place where later botanists always went to see the plant. Many people must have searched in the hope of refinding Lambert’s spot, but they were misled by the idea that it was a woodland species. On the labels of his dried specimens Lambert had given the name of the locality as a wood, and later searchers had taken his statement literally. Mr. Grose knew Tuberous Thistle in various other places, and in his experience he found it a plant of open spaces. Like other searchers, he first looked in Lambert’s wood. Then, thinking the wood unsuitable, he carefully explored its borders. Finally he examined the adjacent chalk downs, and here, in 1942, his search was rewarded by refinding a fine colony of the Thistle. There is, of course, no absolute proof that this is the exact spot where Lambert saw it in 1812, but the probability is extremely strong. The downs here are very inaccessible and vast, with few landmarks, and I had no hesitation in following the original discoverer’s example and using the name of the nearest wood as the locality on my labels. Unfortunately part of this colony of Tuberous Thistle was ploughed up in 1949.

DORSET AND DEVON

Stretching south-west from Salisbury is a long broad tongue of chalk running right down past Blandford and Dorchester. The main road through these towns runs through the middle of some good country. Round the Bokerly Ditch, Martin Down and the Pentridge Hills, the country is open and undulating, and here there is quite a good chalk flora, which is at its best in May. I have noticed Dwarf Sedge, Carex humilis, in great abundance on earthworks in this district, and in one place I found Early Gentian, Gentianella anglica (Plate 19). West of the main road is wooded Cranborne Chase, which is known to have an interesting flora but has been little explored in recent years.

Around Dorchester the chalk is certainly not at its best from the botanical point of view. The archaeological interest of such well-known spots as Maiden Castle and the Cerne Giant is not reflected in the flora, and west of these places the chalk shown on the map is not rich in characteristic plants so far as Dorset is concerned. There are, however, some small but interesting outliers in Devon. The best of these is a strip of coast between Branscombe and Beer. Here the chalk forms fine sea-cliffs and an undercliff with a magnificent flora. There are the usual shrubs—Privet, Dogwood and Wayfaring Tree, over which scramble Traveller’s Joy and Madder, Rubia peregrina. Most of the common downland herbs are present. In addition there is Blue Gromwell, Lithospermum purpurocaeruleum, which in 1938 I saw here in full flower as early as 17 April. It is usually a limestone plant, and this is the only locality where I know it on chalk, though it was formerly to be found on this rock near Greenhithe in Kent. But perhaps the most exciting feature of Beer Head is the addition of maritime plants. Rock Sea-lavender, Limonium binervosum, and Rock Spurry, Spergularia rupicola, both with mauvish flowers, grow in chinks of the vertical chalk cliff. Samphire, Crithmum maritimum, and Portland Spurge, Euphorbia portlandica, are also here. In one place I have seen Hoary Stock, Matthiola incana, on the sea-cliff, but perhaps this is only an escape from gardens. As usual by the sea, the Slender-headed Thistle, Carduus tenuiflorus, is common. Other interesting plants of the district include Nottingham Catchfly, Silene nutans, which is less plentiful than on the Dover cliffs, and Gladdon, Iris foetidissima. A useful account of this chalk flora has been written by Mrs. Clare Harvey, who has drawn attention to the rapid transition on the top of the cliff from chalk to the quite acid soil of the clay which covers it inland. The narrow strip of downland turf, close-nibbled by rabbits, and including such plants as Common Rock-rose, Salad Burnet and Squinancywort, merges into the flora of the clay characterised by patches of Bracken and clumps of Gorse, Ulex europaeus. With the exception of a small area of metamorphosed chalk in Co. Antrim, which is so untypical that it will not be further considered in this book, and a tiny area in Morvern in the West Highlands, the Branscombe chalk is the most westerly in Britain. It is interesting to notice from Mrs. Harvey’s fuller lists how closely the characteristic species present agree with those of our most easterly chalk in Kent. The common plants are almost identical—it is the rarities which differ.

From Dorchester a strip of chalk extends eastwards, forming much of the country behind Lulworth Cove, the Purbeck Hills, and eventually ending at The Foreland by Old Harry Rocks, near Studland. Probably the best known spot on this fine ridge is the mound on which Corfe Castle stands. Around the ruins of the Castle are several plants which may well be relics of cultivation by inhabitants of long ago. Thus there is Borage, Borago officinalis, which is one of our oldest garden herbs. In addition to medicinal uses of the plant, the leaves were added to favourite drinks, and the flowers, which abound in honey, attract bees. In fact, Borage is still grown by bee-keepers, and the seeds were included in a mixture sold for their use which I purchased in 1947. Alexanders, Smyrnium olusatrum, is another plant which may persist here as a relic of ancient cultivation. It was used as a pot-herb. The Shining Cranesbill, Geranium lucidum, which grows on the ruins, is under no suspicion—it is undoubtedly native.

Other plants which have been found on the Purbeck chalk ridge include the Tall and Ivy Broomrapes, Orobanche elatoir and O. hederae, and Mountain St. John’s Wort, Hypericum montanum. On the downs near Old Harry there is Henbane, Hyoscyamus niger, and a puzzling series of Carrots which seem to be intermediates between the Wild Carrot, Daucus carota, and the Sea Carrot, D. gummifer. Yellowwort is far less common on the chalk here than it is on the Jurassic limestones south of Swanage only a few miles away. At Corfe the Fiddle Dock, Rumex pulcher, is exceedingly plentiful. It is easily recognised by the curious warty tubercles on each of the three segments (tepals) which envelop the fruits, by the manner in which the stiff branches spread out in all directions, and also by the fiddle-shaped outline of the leaves.

The wild flower for which this area of chalk is most famous is a very local Calamint, Calamintha baetica, which is not known from anywhere else on the mainland of Britain. It was first found by H. W. Pugsley in September, 1900, when he was impressed by the large size of the lilac-pink flowers; but although he collected further material in 1912, it was not until December, 1922, that he decided to publish it as an addition to the British flora. The plant is well known in Spain (as the name implies) and Portugal, Morocco and Algeria, but seems to skip the intervening French limestones to reappear in Dorset. Calamints are difficult plants to name and many people have difficulty in distinguishing C. baetica from Common Calamint, C. ascendens. When growing, the rare Purbeck species may be known by the more numerous stems, which at first grow along the ground and then ascend, thus forming a “knee,” by the very hairy leaves, and the larger flowers. But the Common Calamint grows near by and it must be admitted that the differences between the two plants are slender. As Pugsley has pointed out, it is interesting that C. baetica should grow on the same chalk ridge, now broken by the sea, as the large-flowered Greater Calamint, C. sylvatica, which is found only in the Isle of Wight.

NORTH WILTSHIRE

Having followed the Dorset chalk into the sea at Old Harry, we must now return to Wiltshire. The Marlborough Downs are immediately north of Salisbury Plain and almost cut off from it by the Vale of Pewsey, exposing Greensand and Gault. Some of the chalk in the immediate vicinity of Marlborough has superficial deposits which bear a calcifuge flora, and, as the mosses show, the Sarsen Stones or Grey Wethers on many of the downs are not calcareous. Probably the finest chalk flora here is that of the escarpment which runs along from Martinsell, Huish Hill, Knap Hill and Milk Hill to Rybury Camp. In one chalky cornfield not far from Marlborough I once saw a fine quantity of Purple Cow-wheat, Melampyrum arvense. This was discovered in 1942, after a gap of 47 years since it was last seen in the county. It also turned up in a clover field near Aldbourne, and it is thought that the seeds may have remained dormant in the soil until war-time ploughing disturbed them.

The main London-to-Bath road runs through a district west of Marlborough where the Tuberous Thistle has been found in a number of places. For most of these we are indebted to the industry of J. D. Grose. The feature of the district which impressed me most on an early visit was the great abundance of the handsome blue-flowered Meadow Cranesbill, Geranium pratense, on the dry roadsides. I first knew this plant as a boy in the water-meadows of the Thames Valley, and to see it in such plenty about the downs, away from rivers, came as a surprise. It compelled complete revision of my early ideas of its habitat requirements. Since then I have seen it elsewhere in equally dry chalky places, but I shall never forget my first visit to Avebury. The lesson is, of course, that only long experience can show to what extent a species is adaptable to different habitat conditions.

In this district the most interesting plants are often to be found on earthworks. Silbury Hill will be a familiar example to all motorists who have driven along the Bath road. A great conical artificial mound, 135 feet tall and nearly a third of a mile in circumference at the base, it has a good flora, including Round-headed Rampion, Phyteuma tenerum. This plant has been known from near here for nearly three centuries. Earthworks both in Wiltshire and elsewhere frequently have better flowers than the intervening downs. Freedom from interference by ploughing, and provision of well-drained slopes which so many chalk rarities favour, are probably the most important reasons.

BERKSHIRE

Much the same type of country stretches north-west to the Berkshire border and continues in that county. First the Lambourn Downs, then Letcombe Castle and the Ridgeway country leading to Ilsley Downs and to the Thames at Streatley. Along this range there are considerable areas where the chalk is covered by other deposits, and in places there are patches of Ling, Calluna vulgaris, on the downs. The general impression one receives of the chalk flora has been well described by Dr. G. C. Druce1 in the words, “softly swelling downs which are studded with Juniper bushes and redolent of Thyme, and brilliant with the orange flowers of Hippocrepis, the Horse-shoe Vetch, and the blue of the Chalk Milkwort.” He adds that “though the number of species composing the down-flora is not large, yet the individuals are in countless numbers and are of a very interesting character.”

This is true enough, but another feature of downland floras is exceptionally well shown here. In addition to the species which are abundant and widespread, there are others which, for no apparent reason, are restricted to very small areas. Thus the handsome flowers of the Pasque Flower, Pulsatilla vulgaris (Plate X), are only to be found very locally in scattered patches. Although there are miles and miles of seemingly suitable country, and although the plant has fruits well adapted for dispersal, and fertile seed is set freely, yet it fails to spread. One of the localities where I have seen it was discovered over a century ago by my great-great-grandfather, Job Lousley (1790–1855).

Another very local plant is the Large Autumn Gentian, Gentianella germanica (Plate 25). It is probably restricted in Berkshire to one earthwork, where it grows with Autumn Gentian, Gentianella amarella. The latter flowers a little earlier than the rarer species, and this is quite a useful character additional to those given in the books. It was from this locality that the hybrid between the two Gentians was first described. As an example of a more widespread plant, which is nevertheless restricted to small areas, Field Fleawort, Senecio integrifolius (Plate 30), may be instanced. This is found at intervals all along the range, but in each place it grows only for a few hundred yards.

From the steep slopes of Streatley Hill (which has long been a famous botanical hunting-ground) the chalk extends on the Berkshire side of the Thames to Reading. About Pangbourne especially there is a good deal of Pale Toadflax, Linaria repens, which shows a decided preference for the chalk. Near Sulham and Tilehurst good chalk plants have been found. Beyond Reading much of the chalk shown on the map is obscured, but there is a nice little bit of downland south of the Thames opposite Bourne End. Here, on Winter Hill, there is an especially fine display of a rather local and large-flowered Eyebright, Euphrasia pseudokerneri. This is only found on calcareous soils and has already been described in connection with Box Hill. Mention must also be made of the interesting flora of the beechwoods of Quarry Wood, Bisham. Just over a century ago the Military Orchid, Orchis militaris, was found here.

This chapter concludes the account of the chalk south of the Thames and seems an appropriate place to refer to the occurrence of calcicoles in the water-meadows. During the course of its long journey the river passes through a great deal of limestone and chalk country, and the streams which discharge into it contain calcareous matter in solution and even in suspension. As far down as the outer suburbs of London the amount of this is surprisingly great. Thus Dr. North states that Thames water near Ditton was found to contain 16.84 parts of calcium carbonate per 100,000, and he quotes the Royal Commission on Water Supply appointed in 1867 as reporting “that the average quantity of dissolved material carried down by the Thames past Kingston was 548,230 tons per annum, of which about two thirds was calcium carbonate; this represents the removal in solution of about 140 tons from every square mile of chalk exposed in the drainage area involved.” Higher up the river the proportion of calcium carbonate is probably just as high, in fact Druce states that some Thames-side meadows contain limestone fragments.

The apparent anomaly of chalk-down plants growing in Thames water-meadows is therefore explained by the basic nature of the silt left behind after flooding. In the higher reaches examples include Burnt Orchid, Orchis ustulata, and Clustered Bellflower, Campanula glomerata. Traveller’s Joy, Clematis vitalba, is plentiful in hedges by the river right down to Kew Bridge and even beyond.

It might be expected that the number of calcicoles would decrease as soon as the Thames left the chalk country, but this is not obviously the case. Many occur in the Windsor meadows, and from Staines, on the Middlesex side, Mr. D. H. Kent lists the following: Traveller’s Joy, Wild Mignonette, Spindle Tree, Common Buckthorn, Salad Burnet, Wayfaring Tree, Clustered Bellflower, Downy Oat, Helictotrichon pubescens, and Upright Brome, Bromus erectus. Some of these species are not strictly confined to calcareous soils but taken collectively they are very significant. Even as far down as Hampton Court he lists eight downland plants, including Small Scabious, Scabiosa columbaria, and Upright Brome. On the Surrey side of the river Dropwort, Filipendula vulgaris, is widespread. Nottingham Catchfly grows near Teddington. It is possible that some of these are relics of a time when the lime content of the soil was higher than it is at present.