THE MAGNESIAN LIMESTONE

![]()

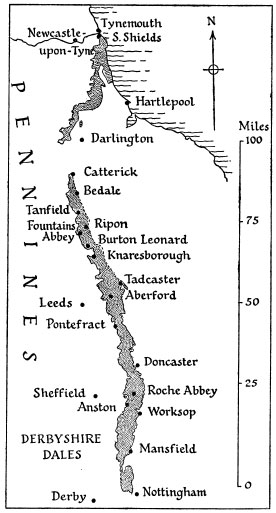

MAGNESIAN Limestone is exposed in a narrow outcrop on the east side of the Pennines. Its southern limit is near Nottingham. From here it extends northwards in a belt some five miles wide by way of Doncaster, Tadcaster, Knaresborough and Ripon. From Darlington it widens and curves eastwards to the Durham coast. The length of the outcrop is about 150 miles and the rocks vary considerably.

The most important geological subdivision consists normally of a thick-bedded yellow limestone containing a higher proportion of carbonate of magnesium than is usual in other limestones. It is to this that the Magnesian Limestone owes its name. When the proportion of that chemical is more than 20 per cent, the rock is known as dolomitic limestone. On the Durham coast as much as 44 per cent of magnesium carbonate may be present, but generally it is very much less.

Dolomitic limestones tend to be slightly heavier and harder than corresponding limestones without carbonate of magnesium. When tested in the usual way with cold hydrochloric acid effervescence is much less brisk than when the calcium carbonate is almost pure. With hot dilute acid they effervesce freely. No ecological comparison between dolomitic and other limestones has yet been made, but it is possible that the differences in chemical constitution may have an interesting influence on the vegetation. Some of the Carboniferous Limestones are also dolomitic.

The Magnesian Limestone is of Permian age. It is older than the Oolites and the Chalk, but more recent than the Carboniferous. It is a relatively soft rock, weathering easily to form rounded hills. Rugged cliffs like those of the Carboniferous Limestone are exceptional but occur in a few places. Because of its softness it gives rise to a good light dry soil suitable for cultivation. For this reason most of the Magnesian Limestone country has been under the plough for centuries and very little of the original vegetation is left. The botanist must search round old quarries for aboriginal turf with its treasures. For other plants the few natural scarps provide the best habitats.

FIG. 13

The Magnesian Limestone

The contrast between the lowland agricultural scenery of the Magnesian Limestone and the upland, or even mountainous, rough crags and uncultivated slopes of the Carboniferous Limestone is very great. The latter provides wild unspoiled country visited chiefly by shepherds and people in search of natural beauty. The former is relatively thickly populated. These differences are evident if a comparison is made between the Derbyshire Dales and the Magnesian Limestone between Mansfield and Worksop in the same latitude. There is an even greater contrast between the Carboniferous Limestone area of Craven in Yorkshire and the corresponding Magnesian Limestone to the east.

The contrast in wild flowers is equally great. It is due less to differences in the character of the limestones than to variation in altitude. Height above sea-level influences the habitat factors under which plants grow—particularly temperature, precipitation, light and wind. On the high Pennine limestones species of northern distribution extend southwards. The Magnesian Limestone running parallel is all lowland. It is only in Durham that it attains an altitude of 600 feet and most of it is less than half that height. Flowers like Hoary Whitlow-grass, Draba incana, which are characteristic of mountain districts, are not to be found.

It is on the soil over this rock that a number of calcicoles reach their farthest north on the east side of England. Traveller’s Joy, which is such a good and conspicuous indicator of calcareous ground, is thought to be native on Magnesian Limestone in south-west Yorkshire, but the reader is very unlikely to see it north of this except perhaps as an escape from gardens. Pasque Flower, Pulsatilla vulgaris, has been recorded as far north as Piercebridge on the Tees, but here, as in several Yorkshire stations farther south, it is now extinct. Nottingham Catchfly, Silene nutans, is still plentiful at Knaresborough but in England does not go beyond.

These are three particularly good examples, but the botanist travelling north along the Magnesian Limestone will be struck again and again with the ever-decreasing quantity of many of the common plants of the southern chalk. Such species as Stemless Thistle, Cirsium acaulon, and Black Mullein, Verbascum nigrum, just peter out. On the other hand, sufficient of the downland flowers extend north on this rock to make it extremely interesting to northern botanists. The flora of parts of the Permian Limestone in Yorkshire reminds me much more of the North Downs than any part of the Carboniferous.

One reason for this resemblance is the greater frequency of orchids. The Bee and the Fly Orchids, Ophrys apifera and insectifera, the Pyramidal, Anacamptis pyramidalis, and the Burnt Orchid, Orchis ustulata, so characteristic of our southern chalk, are still to be found on this formation as far north as County Durham. Spurge Laurel, Daphne laureola, is frequent in the woods. Purple Milk-vetch and Wild Liquorice, Astragalus danicus and A. glycyphyllos, which have been mentioned so often farther south, are widespread.

The southern aspect of the flora is emphasised by the prevalence of Tor-grass, Brachypodium pinnatum. In Derbyshire this is abundant on the Permian. In Yorkshire it is abundant locally on the same formation, and in fact Professor Sedgwick has pointed out how exactly it indicates the line of demarcation where it joins the lower sandstone. But it does not extend into Durham. The interesting fact is that this coarse downland grass is hardly known on the Derbyshire and Yorkshire Carboniferous Limestone, where its place is taken by the related Brachypodium sylvaticum. Similarly Upright Brome, Bromus erectus, is characteristic of the Chalk and the Permian.

There are two rare plants which are associated particularly with the Magnesian Limestone. One is the Thistle Broomrape, Orobanche reticulata (Plate XVII), which is found in Britain only on the Magnesian Limestone from just east of Leeds to Ripon. It is a handsome species some 12 to 20 inches in height, with pinky-grey to amber-yellow flower-spikes to be seen in July. In its first discovered station it was parasitic on the Woolly-headed Thistle, Cirsium eriophorum, but in the place where I have seen it several times in quantity the host-plant is Creeping Thistle, C. arvense. At this spot it grows on a rough common by a busy road, and when the common was ploughed up during the war it was just pure luck that a little corner where the Broomrape grew best was left undisturbed. In all its localities this very rare plant varies a great deal in quantity from year to year. Since it depends for survival on the chance of its seeds falling by a suitable host-plant, picking specimens can endanger its existence.

The second special plant of the Permian is a very inconspicuous little sedge, Carex ericetorum. Most of the other places where this occurs in Britain are in East Anglia, where it grows on chalk and on calcareous sand over chalk, and its occurrence farther north was quite unsuspected until 1943.1 In that year Mr. E. C. Wallace was serving with the R.A.F. at Harrogate and devoting his off-duty periods to botanizing. Early in May he discovered a small patch of aboriginal turf near some old quarries in the Burton Leonard district, and here the rare sedge was growing with a number of other chalk plants. This locality is 150 miles from the nearest place where it was previously known to grow. After it had been shown by this very unexpected discovery that it occurred on the Magnesian Limestone, other botanists started a search to try and fill in the gap in the distibution. A Sheffield naturalist, Mr. John Brown, soon found it at Markland Grips in Derbyshire and on Lindrick Common in the extreme south of Yorkshire. Since then Carex ericetorum has been found in more than one place on the Permian between Wallace’s and Brown’s stations. More recently it has been found on Carboniferous Limestone in Westmorland.

Space will only permit of notes on a few selected habitats on the Magnesian Limestone, and these will be given in sequence from south to north. In Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire the best places are in valleys where wall-like lines of rock have preserved the characteristic flora from destruction, as at Markland Grips, Cresswell Crags and Pleasley Park, and about quarries, as at Shireoaks. At the first-mentioned place Mountain Sedge, Carex montana, grows with C. ericetorum.

A short distance over the county boundary into Yorkshire the wooded crags of Anston have long been famous for their flora. A mile away the main road from Anston to Worksop runs across Lindrick Common on the limestone plateau, and here Stemless Thistle is abundant. Surrey botanists would regard this as one of the commonest of plants, but in the north it is a great rarity. When the Yorkshire Naturalists’ Union went to Lindrick in 1947 they recorded with delight that there was so much of this Thistle that they had to pick their way between its prickly leaves. This place is probably the farthest north that it is plentiful, though it is to be found off the Permian at Rievaulx.

The Magnesian Limestone passes very close to Doncaster on the west side of the town, and some eight miles farther north it forms a most beautiful valley through which runs the River Went. In one place there is a good deal of Spring Cinquefoil, Potentilla tabernaemontani, with other attractive limestone flowers, and I have sometimes turned off the Great North Road at Wentbridge to see these. The main road (A.1) from here runs right along the middle of the Permian to just beyond Wetherby, and some of the best localities can be reached by making only slight diversions.

It is interesting to read the views of a Yorkshire naturalist on the characteristic plants of the Magnesian Limestone about Aberford. The following is taken from the preliminary notice1 of an excursion to this district:

“In the hedgerows Dogwood1, Cornus sanguinea, and White Bryony, Bryonia dioica, with Black Horehound, Ballota nigra, and Tor-grass, Brachypodium pinnatum, may be taken to show quite clearly that we are on Magnesian Limestone, and in a less distinct way we might put Small Scabious, Scabiosa columbaria, Clustered Bellflower, Campanula glomerata, Hoary Plantain, Plantago media, Pyramidal Orchis, Anacamptis pyramidalis, Hedge Bedstraw, Galium mollugo, and Upright Brome, Bromus erectus.”

These, we note, are all common plants of the southern chalk!

Much the same list might be produced from other interesting localities in the same district—from quarries near Tadcaster, roadsides near Collingham, and from Linton Common.

The Permian cliffs above the River Wharfe at Boston Spa and Thorp Arch are wooded and produce chiefly woodland plants. Of the rarer species two of the most characteristic are Wild Liquorice and Purple Milk-vetch, Astragalus glycyphyllos and A. danicus. The former I have only seen near Linton Common on a hedgebank, but the latter has several localities. Fingered Sedge, Carex digitata, is near Boston Spa. There are at least two places in the district where Bane-berry, Actaea spicata, may be still found. This will be described in the next chapter in connection with the Yorkshire Carboniferous Limestone, where it is more plentiful, but its occurrence on the Permian at an altitude of only about 200 feet is interesting. At one place it is still growing at or very near the spot where Ray recorded it in 1670. In a few wet spots Bird’s-eye Primrose, Primula farinosa, is to be found, but this again is much more plentiful on the Carboniferous Limestone.

The town of Knaresborough, by the Nidd, with its Castle, is built on cliffs which are mainly Magnesian Limestone, though the acid Millstone Grit is also exposed. On the calcareous rocks there is an abundance of naturalised plants like Wallflower, Cheiranthus cheiri, Parsley, Petroselinum crispum, and Ivy-leaved Toadflax, Cymbalaria muralis, which are doubtless escapes from ancient gardens. Nottingham Catchfly is still here in its most northern English station, although it has from time to time been reported as extinct. Bloody Cranesbill is also on the cliff with Pellitory-of-the-wall, Parietaria diffusa, and Field Garlic, Allium oleraceum.

Four miles north at Burton Leonard I made a long list of plants from the aboriginal turf which would differ very little from a list made on similar ground at Box Hill in Surrey! Here, and in fact all the way to Fountains Abbey, I was surprised at the abundance of Greater Burnet-saxifrage, Pimpinella major.

The ruins of the Abbey are most beautifully sited in a lovely valley on the Permian limestone. The surrounding woods which are composed mainly of Ash and Wych Elm with a good deal of Yew and Sycamore, Acer pseudo-platanus, extend for over two miles through Mackershaw Wood by the River Skell. Most of the stone used for the construction of this richest of all Cistercian abbeys was obtained from quarries in the valley in which it was built, and the flowers which now grow on the ruins are therefore properly those of the Magnesian Limestone.

Fountains Abbey should be visited by everyone interested in lovely old buildings and their history. To a botanist there are added attractions. For four centuries the flowers have been struggling to establish themselves on the broken walls and, in spite of efforts to keep the place neat and tidy in recent years, they still add charm to the ruin. The most beautiful of all the blooms there are those of the Pink, Dianthus plumarius (Plate 43). The full popular name is “Common” Pink, the prefix being necessary to distinguish it from its allies, but really satisfactory localities for the plant are few and far between. The usual colour of the flower, as its name suggests, is pink, but at Fountains white blooms are not uncommon and there are also some of a much deeper red colour. How long it has been there we do not know for certain, but there is at least a possibility that the Pink has been at the Abbey since the days of the monks. This old-fashioned garden flower has long been a favourite. It is particularly interesting to see the way the plant has climbed the ruins—it certainly ascends to at least 100 feet above ground level and probably higher.

The Permian is a yellow limestone, and the colour of the Abbey walls makes a perfect setting for the flowers which grow on them. Wallflower, Cheiranthus cheiri, and Welsh Poppy, Meconopsis cambrica, are old garden plants which, like the Pink, have found a home here. Ivy-leaved Toadflax, Cymbalaria muralis, is an alien which is thoroughly established. Other flowers I noticed include Pellitory-of-the-wall, Hoary Plantain, Small Scabious, Hairy Rock Cress and Common Lady’s Mantle. Fingered Sedge, Carex digitata, grows in an open space in the woods a mile and a half away and Bird’s-nest Orchid, Neottia nidus-avis, is plentiful under Beeches.

I have never botanized seriously on the Magnesian Limestone north of Fountains Abbey, but it continues past Ripon, Tanfield and Catterick to the Tees at Manfield. In Durham it broadens out to form a triangle with the coast from Hartlepool to South Shields as its eastern edge. It includes Castle Eden Dene, where Lady’s Slipper Orchid, Cypripedium calceolus, was once plentiful. Unfortunately the only recent papers dealing with this area are scattered notes in periodicals and a new full county flora is very much needed. In spite of industrialisation there can be no doubt that interesting plants are still to be found on the Permian in Durham, but it is not a district which appeals to botanists on holiday.

This chapter has covered country from central England to the north. From Nottingham and Derbyshire the journey has led far past the main mass of the Yorkshire Carboniferous Limestone with which the early part of the next chapter is concerned. But this is the usual approach of visitors from southern or central England who travel by road. They follow the Great North Road to Doncaster and along the stretch of Magnesian Limestone described, through Aberford and Bramham, and then turn west along the valley of the Wharfe. It is with Upper Wharfedale that the next chapter is first concerned.