‘We still need to assimilate the experience of modern war … neither here, nor today will the outcome of the war be decided. The crisis is yet far off.’1

MARSHAL SHAPOSHNIKOV, DECEMBER 1941

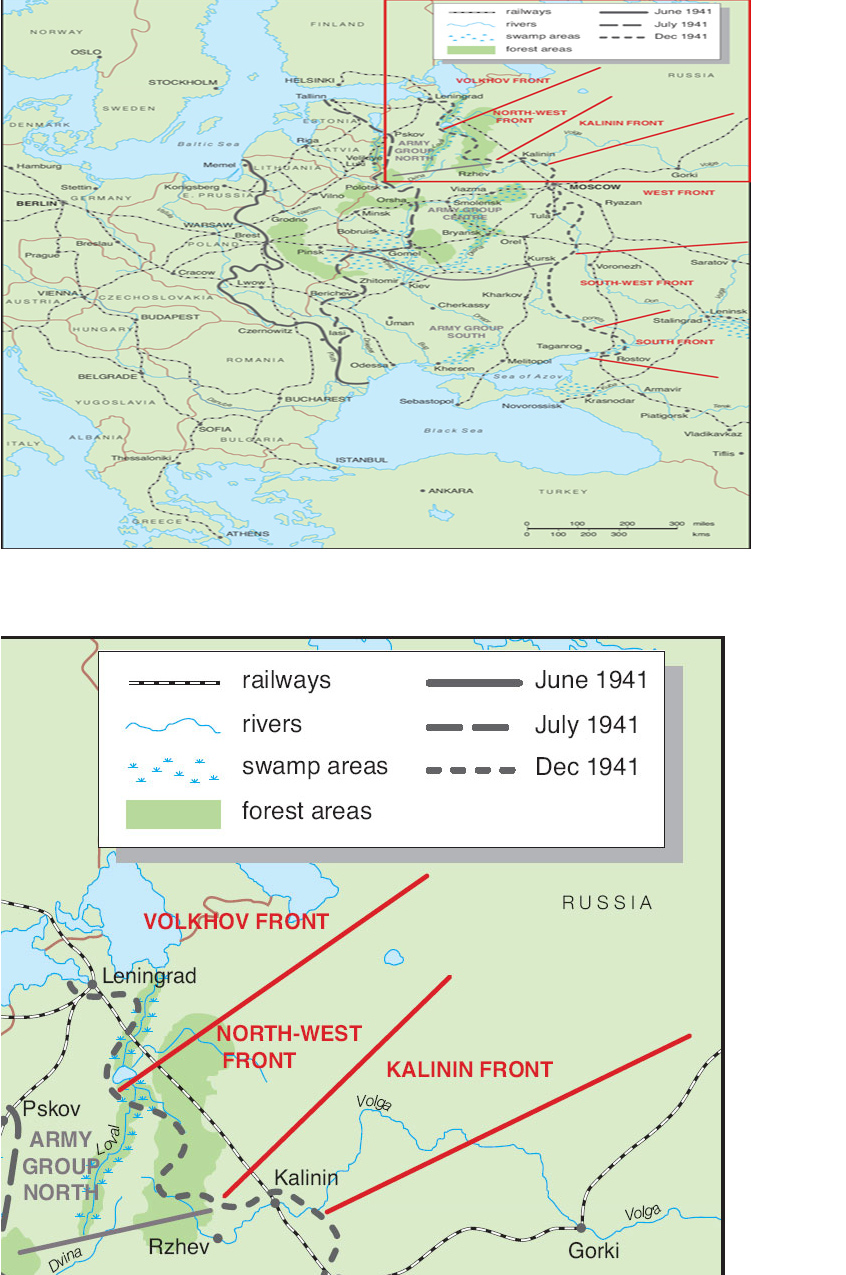

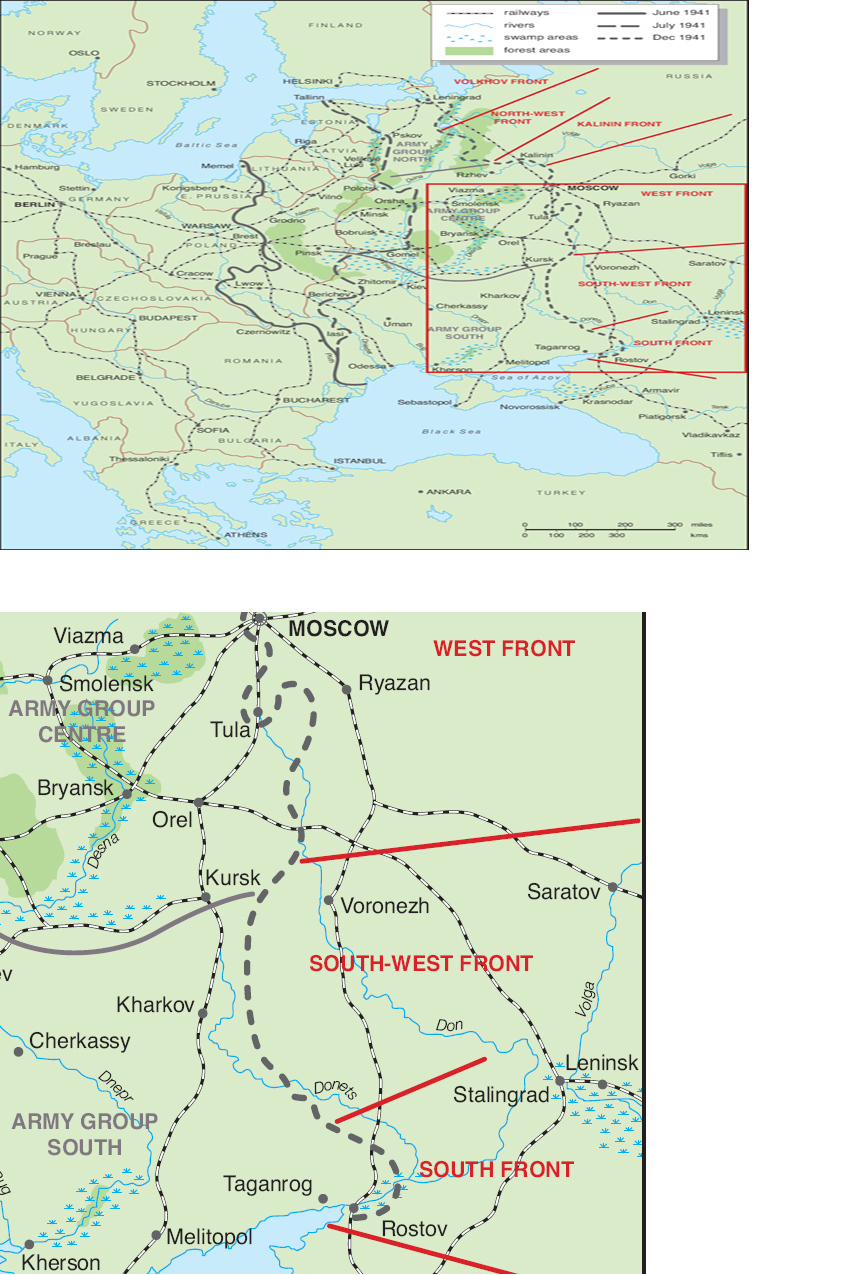

The dramatic reversal of fortunes at the gates of Moscow encouraged Stalin to make the same premature assumption of victory that Hitler and his generals had been led to by the great battles of encirclement in the summer of 1941. No matter that Zhukov had husbanded the newly mobilized and only half-trained reserves to make the Moscow counter-attack possible; that he had been supported by the majority of the Red Air Force; and that the Germans had been at the extreme end of their tenuous supply lines. Stalin ordered immediate offensives all along the line from Leningrad to the Crimea.

The attempt to break the siege of Leningrad relied on the Volkhov Front, named for the river that flows north from Lake Ilmen into Lake Ladoga. In command was another youthful survivor of the purges, 43-year-old Kirill Meretskov, a veteran of the 1st Cavalry Army from the Civil War who had served in Spain alongside Pavlov. As commander of the Leningrad Military District in 1939 he had presided over the less-than-successful assaults on the Mannerheim Line at the end of that year. In January 1941 he was sacked for a dismal performance in a wargame and replaced by Zhukov. Worse was to follow: in the wake of Pavlov’s arrest, he too was seized and tortured into confessing he was part of Pavlov’s conspiracy. For reasons lost in the torturers’ archives, he was still alive in September 1941 and was released without explanation and restored to his rank.

The Volkhov Front was created in December 1941. On 7 January it launched its offensive and was reinforced with the 26th Army from Stavka reserve a week later. The 26th ploughed ahead and was re-named the 2nd Shock Army, one of four ‘breakthrough’ forces intended to have extra artillery to batter their way through the German defences. In the event, the 2nd Shock made such progress that it found itself in a deep salient. The Russian attacks stalled in the dense forests and the fighting reverted to positional warfare. Attacks and counter-attacks saw bunkers and trench lines change hands repeatedly, but changes to the front line only showed up on tactical maps of the smallest scale. The tables were turned in March 1942 when the German Army Group North counter-attacked at the base of the salient and encircled 2nd Shock Army. After the commander of the army fell ill, Meretskov sent his new deputy, Andrei Vlasov, to take charge of the pocket.

Vlasov, who had had some experience of breaking out of German encirclements the previous summer, was once again the victim of confused and disastrous command arrangements. He managed to establish a tenuous line of communication to the rear, but his position was untenable. Stavka disbanded the Volkhov Front, which had little to show for an estimated 95,000 casualties. Meretskov’s heart must have been in his mouth when this, his first operation since his release from jail, went so terribly wrong, yet the army group was re-formed in June and he was put back in charge. But from April to June this left the Leningrad Front trying to run nine armies, three independent corps and two battle groups; Vlasov received neither reinforcements nor permission to withdraw. When the rasputitsa finished at the end of May, the Germans closed the ring again. The modern Russian official history blames the commander of the Leningrad Front, Colonel-General Mikhail Khozin, who failed to act on Stavka instructions issued in the middle of May to withdraw 2nd Shock. Khozin was demoted to command the 33rd Army, but later climbed back to army group command; he lived until 1979. Vlasov’s men fought on until the end of June when they capitulated. Very few survived the war.

The German blockade of Leningrad continued. There was little thought of storming the city, merely bombing and shelling it and allowing the sub-zero temperatures and lack of food to do the rest. Hitler had publicly stated his intention to level the place. Although the famous railway across the ice brought in some supplies across the frozen Lake Ladoga, hunger turned into starvation in the winter of 1941–42, and more than half a million people perished. The bodies could not be buried and the city’s sanitary system broke down. Only the intense cold prevented an epidemic. The local NKVD were predictably busy, enforcing ‘the discipline of the revolver’: the secret police executed about 5,000 people in the first year of the siege. The stubborn, determined resistance of Leningrad is little known in the west, and Stalin, who pointedly never visited the city afterwards, took care it was not even commemorated in the USSR.

The siege would eventually last for 900 days, but Stalin’s response to this epic defence was to purge the Leningrad party after the war, possibly assassinating the former Party boss Andrei Zhdanov in 1948 and removing senior figures associated with him and the city. Two thousand functionaries and Party officials were sacked and around 200 executed. Lieutenant-General Alexei Kuznetzov, Chief Commissar of the Leningrad Front, was arrested in 1949 on false charges of treason and executed in 1950. (Khruschev posthumously rehabilitated him and many other victims of this purge in 1954.) The brilliant technocrat Nikolai Voznesensky, Deputy Premier and organizer of Russian industry, was another prominent victim of the ‘Leningrad Affair’, murdered in the back of a van in 1950.

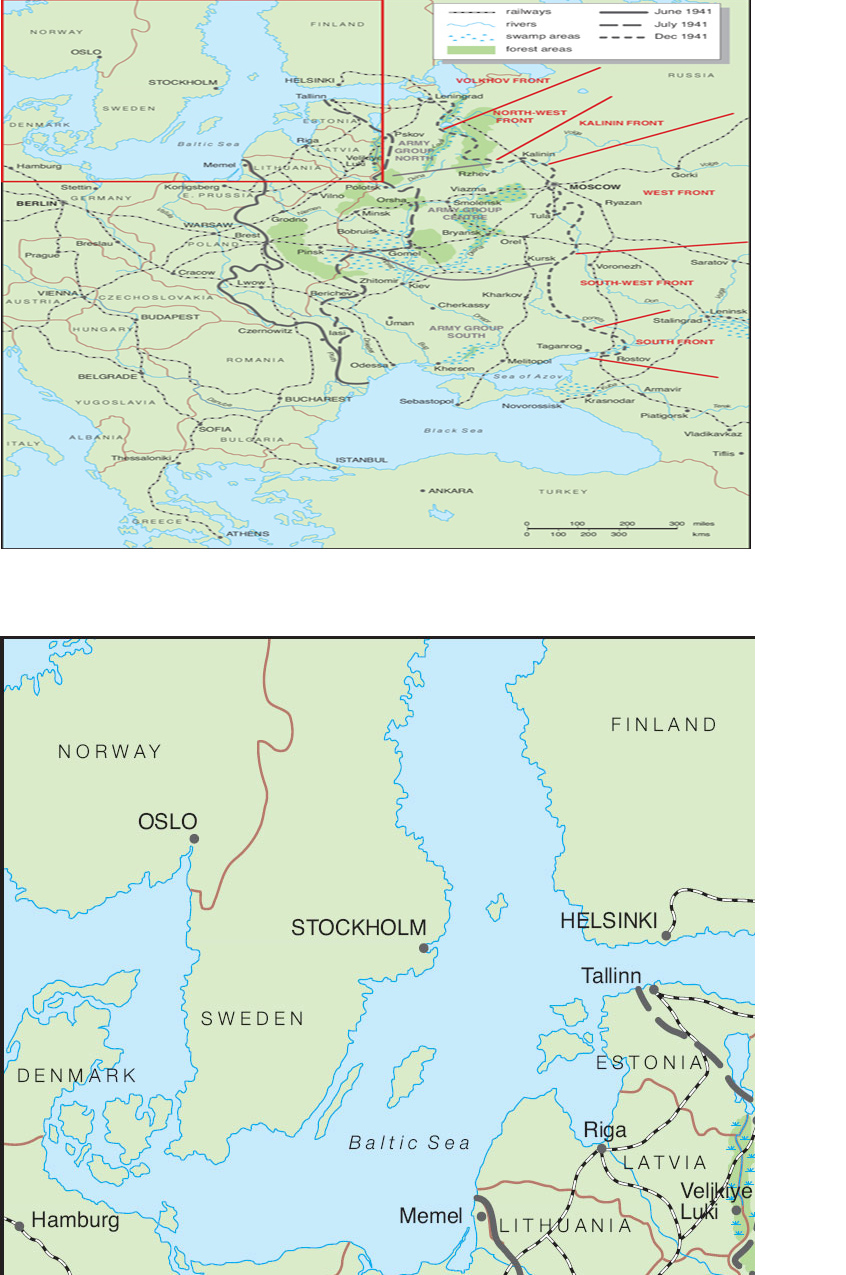

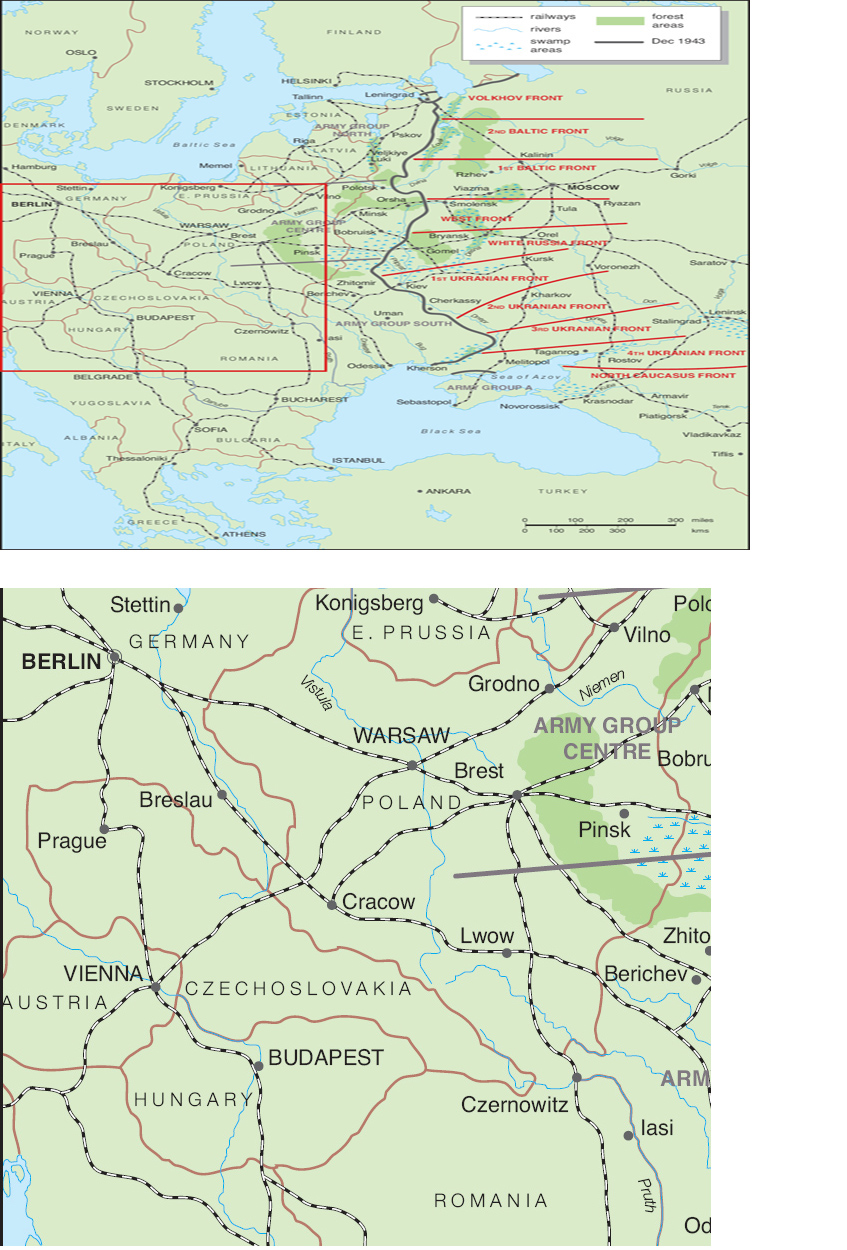

In the Moscow area, the temperature sank to -25ºC in January. The Kalinin and Western Fronts were ordered to destroy Army Group Centre, and came desperately close to doing so. The Germans reeled back, and before a coherent front line could be re-established, Russian cavalry units had penetrated far behind the lines, where they would remain a threat to German communications until the spring. Two Soviet armies, the 29th and 33rd, were cut off by German counter-attacks, forming pockets that were slowly reduced as better weather enabled German armour and aircraft to operate again.

In the harsh weather conditions, neither side managed to mount effective air attacks. The Luftwaffe had failed to seriously interrupt the evacuation of Soviet industries out of reach of German attack: the army’s demand for close air support was unceasing and left no opportunity for strategic air missions. German aircraft did mount a few missions against Moscow, beginning with a major raid on the night of 21 July, when 127 bombers delivered 104 tons of bombs on the Soviet capital. The Russian response was a token bomber raid made on Berlin by 18 Ilyushin Il-4s of the Baltic Red Banner Fleet’s torpedo/mine air wing on 6 August. The German raids on Moscow prompted more bombing by the Soviet long-range air force in September, but the advance of the Ostheer quickly put most Russian airfields beyond range of Berlin. A couple of night raids on a similar scale by the Luftwaffe hit a number of famous landmarks, and the Japanese embassy. The German bombers had even launched some daylight raids in the autumn, once they had fighter airfields within range, but the demands for tactical air support soon reduced attacks on Moscow to nuisance strikes by a few dozen aircraft at night. The other vital strategic target, the Soviet rail network, had been left alone too for the same reason.

The Red Air Force was conspicuous by its absence when the Germans fell back from their most advanced positions near Moscow. In December 1941 and January 1942, the Germans had very few metalled roads along which they could retreat. These highways, which the engineers worked like demons to keep clear of snow, were crowded with men and vehicles. The Luftwaffe was only able to mount a token effort to protect them with fighters. Yet they were hardly ever attacked from the air.

The Red Army’s advances trapped similar numbers of German troops behind the lines. Three important ‘pockets’ survived, largely by aerial resupply. At Demyansk, six German divisions under General von Seydlitz held out until relieved in late March. Von Seydlitz was later to play a key role at the battle of Stalingrad, where he was captured, and became a leader of anti-Nazi German prisoners in Russia, calling on their former comrades to overthrow Hitler. He was a veteran of Germany’s previous war in the east, and had been involved in an earlier battle of encirclement at Brczeziny, near Lodz, in 1914. He led a breakout from Demyansk, an epic 30-day battle of endurance that ended just as the spring thaw imposed a halt on operations. The Luftwaffe’s success in sustaining these trapped forces would later be seized upon by Hitler and Göring in November 1942, when the 6th Army was surrounded at Stalingrad; both chose to ignore that Von Seydlitz’s force was far smaller. They also overlooked the sorry state of Von Seydlitz’s survivors. The High Command saw divisions rejoining, albeit without their heavy weapons. They could be replaced, but the mental and physical consequences of living and fighting in this frozen wilderness without nourishment, sanitation or medical facilities were harder to overcome.

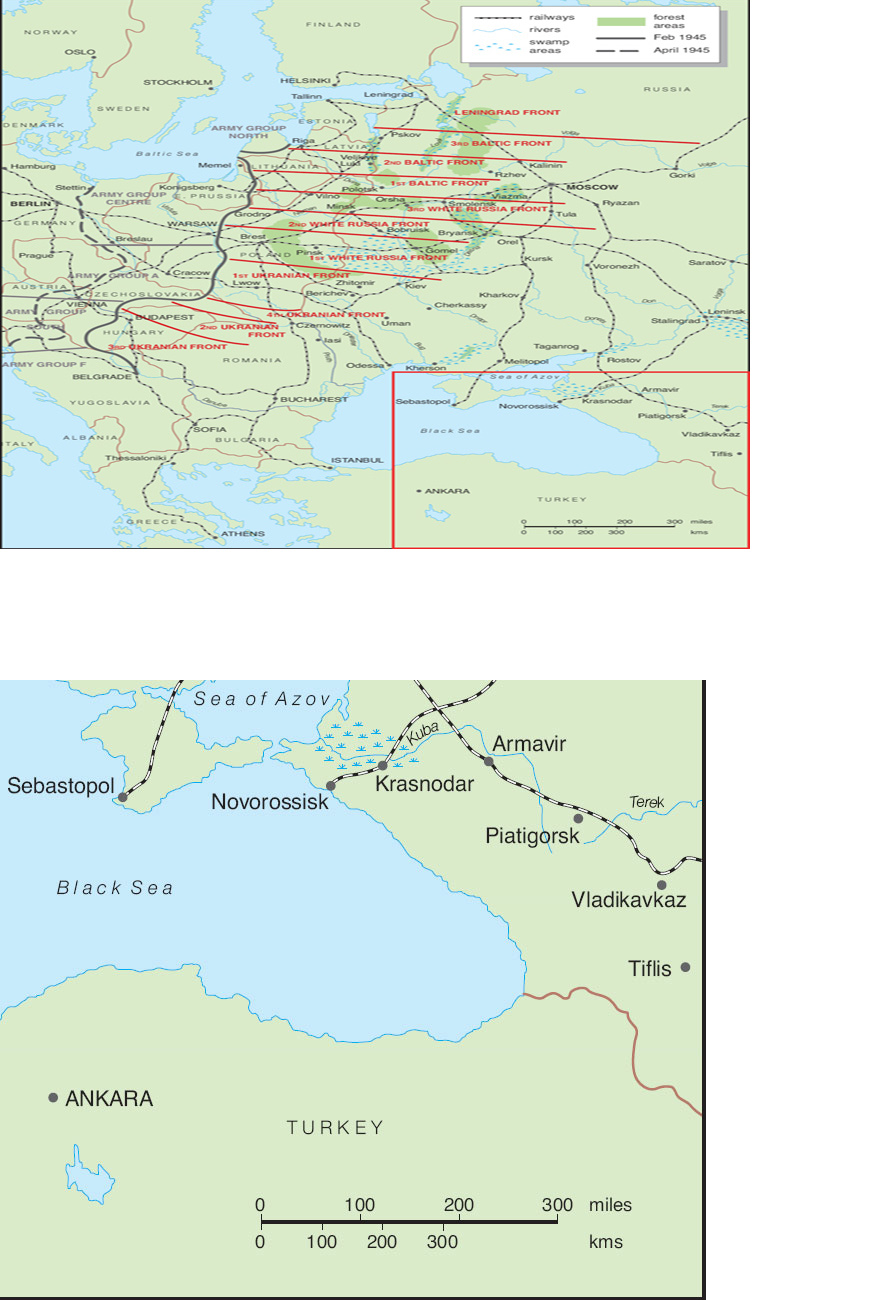

Meanwhile, in the Ukraine, an offensive south of Kharkov pushed a 70-mile salient into German lines and established a bridgehead on the west bank of the Donets. An amphibious assault re-established a Russian presence on the Kertsch peninsula, held by a single German division, the 46th, while the rest of Von Manstein’s 11th Army fought its way into Sebastopol. The 46th Division made repeated requests to withdraw from the peninsula, which Von Manstein turned down, sending his only reserve, two brigades of Romanian mountain troops. The Soviets recaptured the port of Feodosia in a night-time amphibious operation, threatening to cut off the 46th Division. The commander of 30th Corps, Lieutenant-General Hans Graf von Sponeck, gave the order to retreat, despite explicit instructions to stand firm. The line was stabilized at Parpach and Feodosia, the latter eventually re-taken by a counter-attack from 15 to 18 January. At the insistence of the fervent Nazi Field Marshal Walter von Reichenau, commander of Army Group South, Sponeck faced a court martial and was sentenced to death. The regiments of the 46th Division were stripped of their awards and battle honours – the only time this happened to an army formation during the war. Some accounts claim the divisional commander, Lieutenant-General Kurt Himer, was retired in disgrace, but he was still with the 46th Division three months later when he died of wounds on 26 March.2

The spring thaw found the German Army holding its positions some 180 miles west of Moscow, the sort of distance the Panzer spearheads had covered in less than a week in the summer of 1941. Small wonder then that Stalin concentrated his forces on the Moscow Front, in expectation of a renewed drive on the Soviet capital. On a map, the German threat looked very obvious: a salient centred on Rzhev pointed at Moscow like an arrowhead. Behind it lay the trapped Russian 33rd Army. To the north, Russian forces had driven the Germans back to Veljkiye Luki, the front line dipping south to within 60 miles of Smolensk. To the south, the Russian drive on Bryansk had been stopped well short of the city: Kursk, Belgorod and Kharkov all remained in German hands.

Casualties had been unprecedented. From the invasion to the end of November the Ostheer had suffered 743,000 casualties, of whom 200,000 were dead. By comparison, German losses in the invasions of Belgium, Holland and France were 44,000 dead and 156,000 wounded. The fighting outside Moscow from December to January cost another 55,000 dead and 100,000 wounded. Panzer divisions were lucky to have 20 operational tanks by early 1942: three-quarters of the approximately 1,000 tanks assembled for Operation Typhoon were lost by 4 December. The Luftwaffe had lost 758 bombers, 568 fighters and 767 other aircraft destroyed; 473 bombers, 413 fighters and 475 other aircraft were damaged.

Soviet losses were astronomical. Every mechanized corps and 177 rifle divisions had been written off. About 1,000 vehicles remained from the pre-war tank fleet of some 22,000. The defence of Moscow and the counter-attack that followed had cost nearly a million casualties. More than three million Red Army soldiers were taken prisoner in the headlong German advance of 1941.3 By February 1942, only about a quarter of a million remained alive.

Many Red Army units caught behind the German lines in the initial invasion did not surrender. Instead, they melted into the forests and swamps, to re-emerge when the German forces had passed eastwards. As early as July 1941, German commanders were reporting attacks well behind the lines, launched by cut-off units of the Red Army and local volunteers. The Partisan War had begun.

Despite its previous association with guerrilla warfare, the Soviet regime discovered a severe shortage of experienced guerrilla commanders in 1941. Stalin had executed most of the Bolshevik ‘Old Guard’ and there had been no preparations for resistance activity in the late 1930s. All pre-war Soviet war plans assumed a conventional war in which the Red Army would take the offensive. Stalin’s future successor, Nikita Khruschev (then Party boss in the Ukraine), issued the first call to arms in June 1941, with Stalin taking up the theme of guerrilla struggle in his radio address to the nation in July.

As the German advance swept deeper into the USSR, so NKVD and Party officials attempted to organize guerrilla units in its wake. Initial attempts were not successful. In the open country of the Ukraine there was nowhere for the partisans to hide, and the local population was welcoming the German tanks with flowers. Resistance efforts foundered in the Crimea too, where the disaffected Tartar population helped the Germans hunt down the guerrillas. (This would neither be forgotten nor forgiven.) The NKVD continued its mass arrests in the Baltic Republics, but the Red Terror proved as counter-productive as later German policies. Local people anticipated the arrival of the Germans and began attacking Soviet installations.

By early 1942 the Partisan movement had yet to make a serious impact on the war. Although a central command system had been created in Moscow to coordinate the campaign behind the lines, there were probably no more than 30,000 guerrillas in the field.4 However, a nucleus had been created. The remnants of Red Army units, in some areas reinforced by forces cut off after the failed counter-offensives in the spring of 1942, combined with Party activists and locals who had discovered the nature of Hitler’s ‘New Order’ for themselves. The blind savagery with which the German Army treated the conquered peoples of the USSR soon alienated many potential sympathizers, and news spread of the prisoner-of-war camps, where more than two million soldiers had met their deaths during the winter.

Behind the Russian lines men and women were struggling to survive too. In sub-zero temperatures, sometimes in near-total darkness, they unloaded machine tools from rail cars and reassembled whole factories in remote areas. The success with which Soviet industry was evacuated east in 1941 was justly celebrated by the USSR as a triumph as significant as any victory on the battlefield. Indeed, it was the foundation of all subsequent victories. Iron, steel and engineering plants were shipped to the Urals, Siberia or Kazakhstan in some 1.5 million wagon-loads. A total of 16 million people went with them, labouring with grim determination to get the machines turning again. The Yak fighter factory in Moscow was dismantled and shipped to Siberia, where production resumed after just six days on site. In three months production exceeded the quotas achieved in Moscow.

The Herculean efforts of the Soviet industrial workforce enabled the Red Army to re-equip in time for the 1942 campaigns. Many German memoirs stress the overwhelming numerical and material superiority of Soviet forces, but in 1942 it was Germany that enjoyed every industrial advantage, with the factories of most of Europe at her disposal. German steel production, for example, was four times that of the USSR.5 Nevertheless, even in the second half of 1941, in the middle of the relocation programme, the USSR built more tanks than German factories delivered in the whole year. Soviet industry delivered 4,500 tanks, 3,000 aircraft and 14,000 artillery pieces to the Red Army between January and May 1942. During that whole year, Soviet production figures would reach 24,000 tanks and self-propelled guns, 127,000 guns and mortars and 25,000 aircraft. Comparable German figures were 9,000 tanks, 12,000 guns and mortars and 15,000 aircraft. Note the yawning disparity in artillery manufacture. The growing gulf in Soviet and German industrial production would not begin to transform the situation at the front until late 1942. Meanwhile, as the floods caused by the spring thaw began to subside, both sides prepared to take the offensive – and in the same area.

The Soviet blow fell first. Emboldened by the Red Army’s winter victories, Stalin ordered immediate offensive action to follow the spring thaw. However, Marshal Boris Shaposhnikov, Chief of the Red Army General Staff, and the Chief of the Operations Department, General Alexander Vasilevsky, both counselled caution. They argued that the winter offensives had only succeeded because the Germans were poorly equipped to fight in what had been, even by Russian standards, a very harsh winter. Come the spring, there was no reason the enemy could not repeat the lightening advances of summer 1941. These more thoughtful Red Army leaders recognized their forces still had no answer to German tactical skill and professionalism, nor the formidable striking power of the Luftwaffe. The German front line lay within 200 miles of Moscow, which the Panzers had proved they could cover in a week. Shaposhnikov and Vasilevsky wanted to dig in, to fight the enemy from carefully prepared positions and not try to take on the veteran Panzer divisions in mobile warfare. It was to be another year before this more cautious strategy would be tried to defeat a German summer offensive.

Zhukov characteristically wanted to attack the Germans head-on, on the Moscow Front, believing that by getting his blow in early he could inflict major damage before the Germans had fully re-equipped. Stalin liked the idea, but not the choice of direction. He favoured the southern sector, where Marshal Timoshenko had made two successful assaults on the German lines south of Kharkov. In January, the Soviet 6th, 57th and 9th Armies had attacked the German lines around Iszum along the northern Donets River. Ski troops and three cavalry corps exploited 50 miles further, seizing the rail junctions of Barvenkovl and Lozovaya before German reserves arrived to re-establish the front. The resulting salient lay between two strategic objectives, the city of Kharkov to the north and the Donbas industrial region to the south. It was an obvious springboard for a future offensive. On 7 March Timoshenko’s South-Western Front attacked again, north-east of Kharkov, and established a second, smaller bridgehead across the northern Donets. Kharkov was now menaced from north and south, and Timoshenko was eager to attempt a larger offensive, although efforts to deepen the north-eastern bridgehead at Stayri Saltov continued for several weeks without making significant progress. April brought the spring thaw: the roads dissolved into swamps and Timoshenko departed for Moscow to plead his case.

Two false assumptions underpinned Stalin’s strategy for the spring. Firstly, the Red Army leadership unanimously expected the German summer offensive to head straight for Moscow. Secondly, his generals grievously underestimated the Wehrmacht’s powers of recovery and thus the strength of the German forces overall, and in the southern sector in particular. Stalin gave his blessing to Timoshenko at a meeting in the Kremlin at the end of March, but did not give the fire-eating cavalryman all the forces he requested as they would be needed to repel the anticipated German drive on the capital.

The classified post-war Soviet General Staff study of the Kharkov theatre of operations in May 1942 laments the ‘treacherous’ delay by the Anglo-American forces in the summer of that year. It claims that this was a cynical betrayal by the western Allies that enabled the Germans to re-deploy their forces, thus regaining the initiative they had lost during the winter. Future premier Nikita Khruschev was the South-Western Front’s Commissar at the time, and shares responsibility with Timoshenko for what happened when the Red Army launched its first major strike against a German Army no longer enfeebled by the grip of winter. So when the official history was published under his aegis, they blamed Stalin, who was safely dead at last.

The sector of the German lines selected for the Red Army’s breakthrough was held by the 6th Army, commanded by one of Hitler’s favourite generals, Friedrich Paulus. As a staff officer, Paulus had played a key role in planning the 1941 invasion, and only Rommel would be promoted at the same meteoric rate, from lieutenant-general to field marshal in a year. The 6th Army was the largest of the German armies on the Russian front, and the Red Army’s numerical advantage for this battle was but a fraction of the odds it would enjoy by the end of the war. Even in the sectors selected for the main thrusts, the Russians had a 3:1 advantage in armour and infantry, and only 2:1 in artillery. Red Army doctrine called for a deception plan to be part of any offensive operation, yet in spring 1942, neither senior officers nor junior ranks had learned the sort of skills that would later wrong-foot their opponents. Soviet preparations involved a considerable amount of lateral movement, and the arrival of additional forces along the front did not go unnoticed by the Germans. The thaw worked in favour of the Germans, hindering Russian troop movements and channelling them along the few hard-surface roads.

The offensive began on 12 May from both salients. On the northern one, the 21st, 28th and 38th Armies found the going unexpectedly tough. German strongpoints were plentiful and well camouflaged; many escaped the preliminary bombardment and all held on tenaciously even when surrounded. The Russians were being broken on just the sort of chequerboard defences that cost the British such heavy loss of life at Passchendaele in 1917. Some units pressed on, while others became pinned down between German positions. Coordination between tanks and infantry remained poor. Most of the 19 tank brigades employed in the offensive were directly subordinate to rifle divisions, but they tended to fight quite separate battles, taking turns to attack rather than working in harmony. Although the Russian tank regiments included both KV-1 heavy tanks and T-34s, without infantry or artillery support they were knocked out in large quantities.

After two days’ fighting, the northern bridgehead had been deepened to more than 12 miles at its greatest extent, but losses had been heavy. Counter-attacks by the German 3rd and 23rd Panzer Divisions brought the advance to a sudden halt, and the bulk of the Russian armour was re-deployed to fend them off. Better progress was made in the south, where the Soviet 6th, 57th and 9th Armies struck west towards Krasnograd and Pavlograd. By nightfall on 12 May they had broken through along a 25-mile frontage and advanced up to 10 miles in places. This brought them to the Germans’ secondary defensive positions along the Orel River. Steady progress continued for the next 48 hours, with one Hungarian and several German infantry divisions overrun; some Soviet units advanced 25 miles west of their start line. It all appeared to be going so well.

It could have gone even better had the South-Western Front’s armoured reserve been able to take advantage of the German disarray. But the 21st Tank Corps was stuck 25 miles behind the Russian 6th Army; the 23rd Tank Corps was 12 miles behind; and the two reserve rifle divisions were between 12 and 25 miles in the rear. Timoshenko’s operational plan assumed that the known German reserves would take five or six days to reach the front line, but the Germans were faster off the mark. The absence of the Soviet second echelon forces, combined with the aggressive reaction of the German reserves, ground down Timoshenko’s leading units, and the Russian advance faltered.

Heavy fighting continued north-east of Kharkov from 14 to 16 May, but without any significant advances. Meanwhile, the Barvenkovo salient continued to deepen as Timoshenko’s armoured reserve pressed westwards. By nightfall on 16 May a Soviet cavalry corps was in action on the outskirts of Krasnograd. Timoshenko signalled his progress to Moscow, blissfully unaware that every mile west his soldiers travelled, the deeper they were sticking their collective heads into a noose. At dawn on 17 May Panzergruppe Kleist assaulted the south-eastern side of the salient, driving hard for Barvenkovo and with every intention of cutting in behind Timoshenko’s main forces. The 3rd Motorized Corps was a cosmopolitan band comprising the Romanian 20th Division, German 1st (Bavarian) Gebirgsjäger Division, 100th Jäger Division (from Vienna), 60th Motorized and 14th Panzer Division (based at Dresden) with 170 tanks. It attacked on a 40-mile front with its main effort concentrated on a 13-mile sector. The 44th Corps – four infantry divisions and 16th (Westphalian) Panzer – struck the point at which the Russian front line curved from north–south to east–west, the very corner of the salient. It says much for the sheer size of this theatre of war that even in a full-scale counter-offensive, the average frontage occupied by the 11 divisions Von Kleist committed to the operation was more than 6 miles.

The Russian 9th Army was the first victim of Panzergruppe Kleist; outnumbered nearly 2:1 in infantry and 6:1 in tanks, it was simply flattened. Its front line was penetrated by 8.00am, and at noon the 14th and 16th Panzer Divisions were up to 12 miles inside the salient. The 257th (‘Bear’) Division reached the Donets, a welcome sight in 30°C heat. Vehicles and men alike were covered in dust from the fine black earth. On 18 May the Germans overran the headquarters of the Russian 57th Army, which was commanded by General Kuzma Podlas. The 49-year-old former deputy commander of the Kiev Military District had been arrested in 1938 and condemned to a five-year jail term. Podlas was one of the fortunate few to be released in 1940 and restored to command. He tried to fight his way out, but was killed in action. Barvenkovo fell that afternoon. Engineers of the 101st Jäger Division lifted some 1,750 mines in one day as they battered through the Soviet defensive lines south of Iszum.

The village of Ternovaya, held by elements of the German 429th Infantry Regiment (294th Division), had been surrounded in the initial Soviet attack on 12 May. Resupplied by air – Soviet reconnaissance reports claimed by paratroops – the garrison held on until 17 May, when it was relieved by elements of 3rd Panzer Division. A counter-attack the next day left it surrounded again as the Russian 38th Army resumed its attack to draw off German reserves. Timoshenko had ordered his exhausted troops north-east of Kharkov to continue attacking in order to prevent the Germans dispatching the 3rd and 23rd Panzer Divisions to the south. Nevertheless, the Germans did switch both tank formations to the south on 21 May. Timoshenko requested reinforcements from the Stavka, which granted him two rifle divisions and more armour, but these fresh formations were several days’ journey from the battlefront. Even so, he seems to have misjudged the pace of the German breakthrough and was still ordering the Russian 6th Army units opposite Krasnograd, in the very nose of the salient, to continue attacking. His report to the Stavka on 19 May, countersigned by Khruschev, gave the impression, of course, that all was under control and that offensive efforts towards Kharkov were still under way.

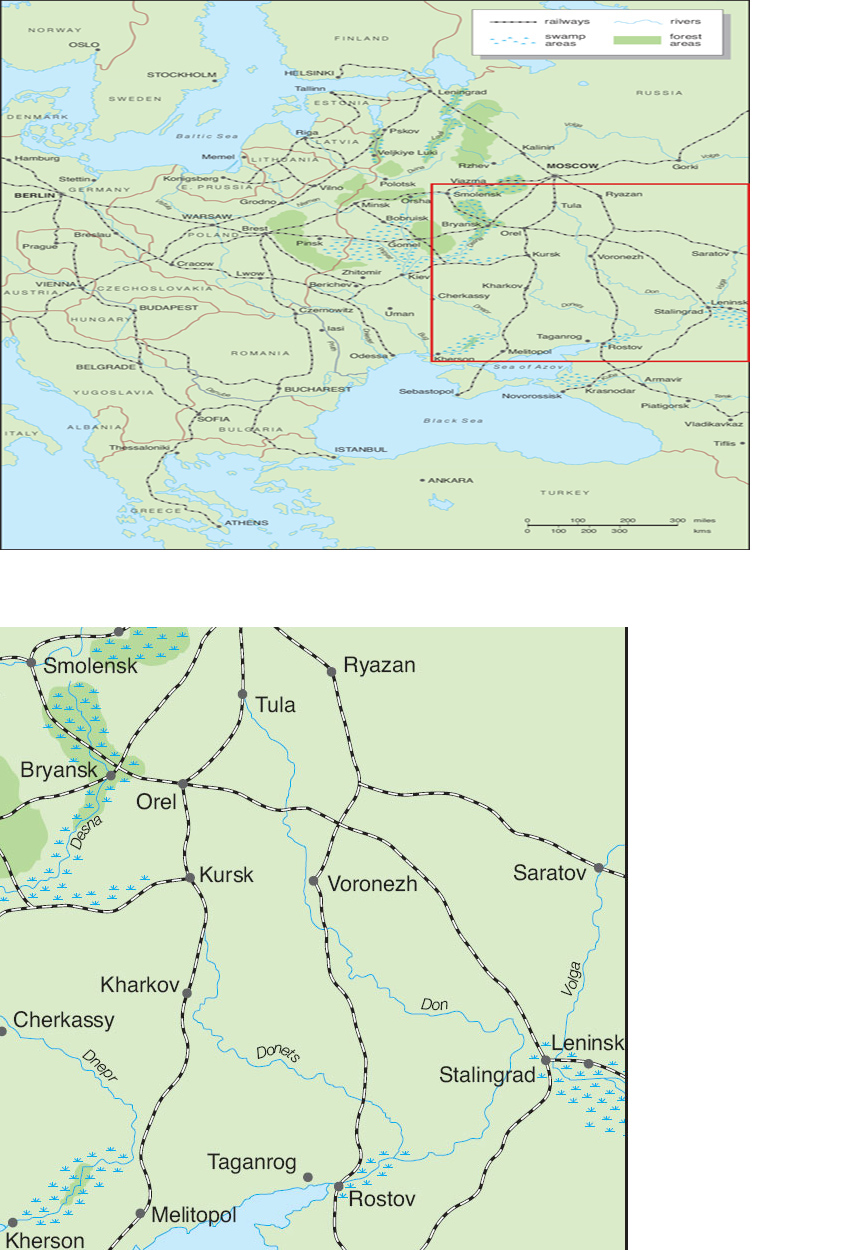

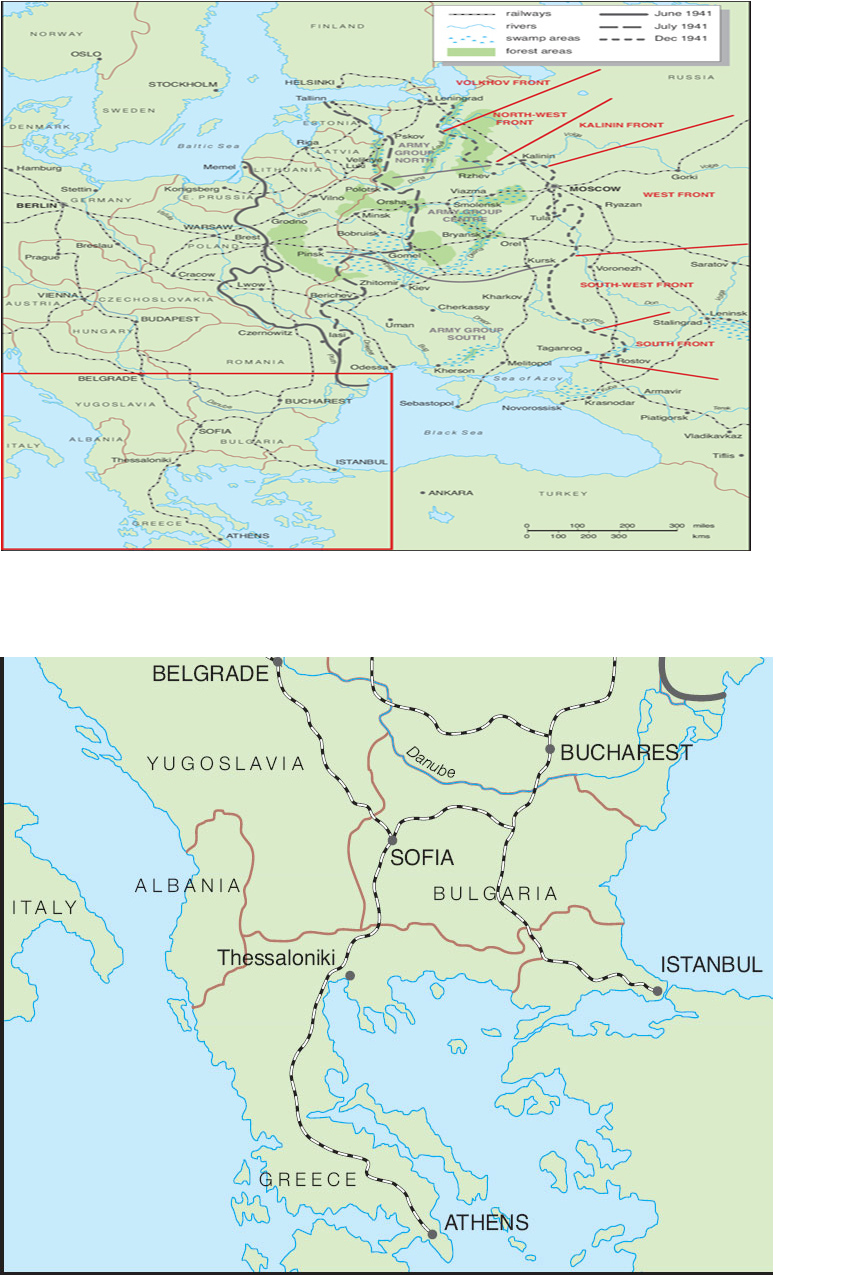

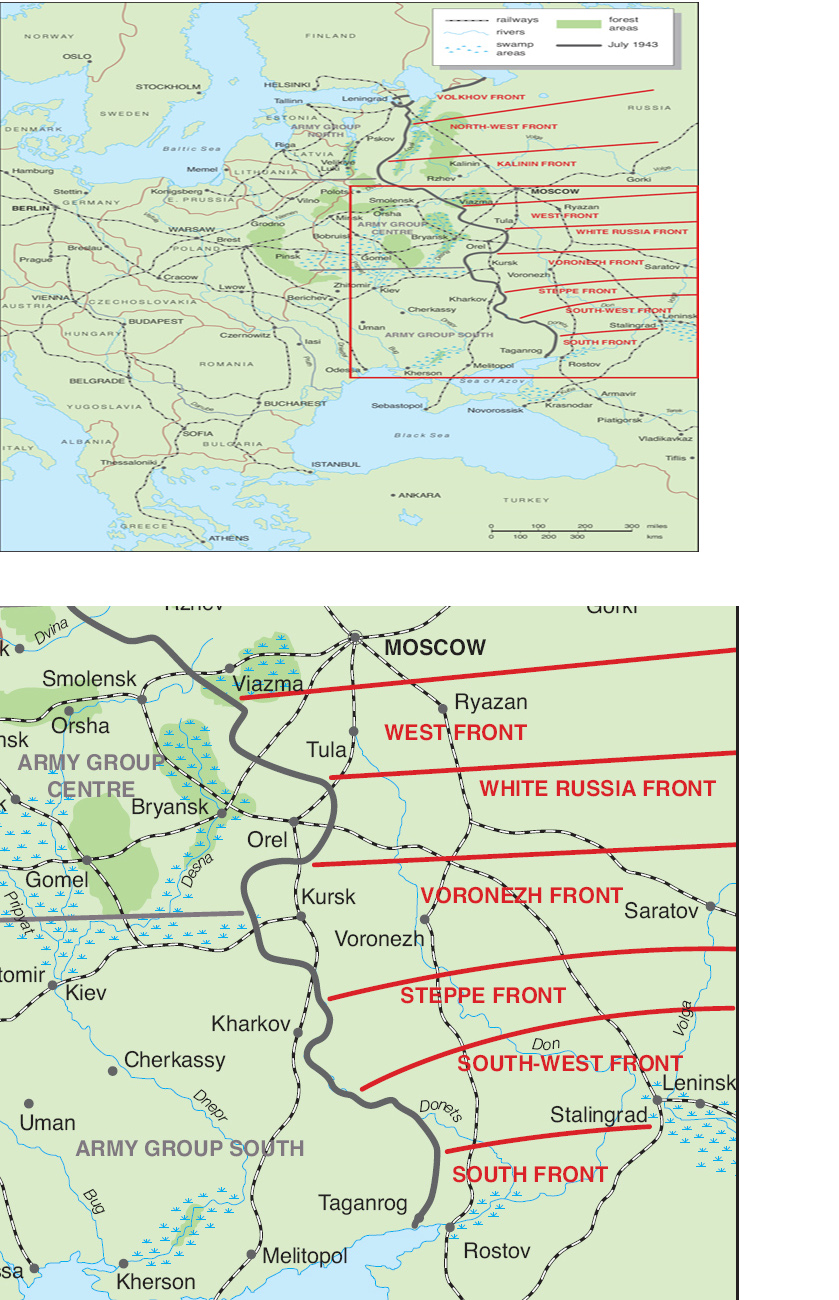

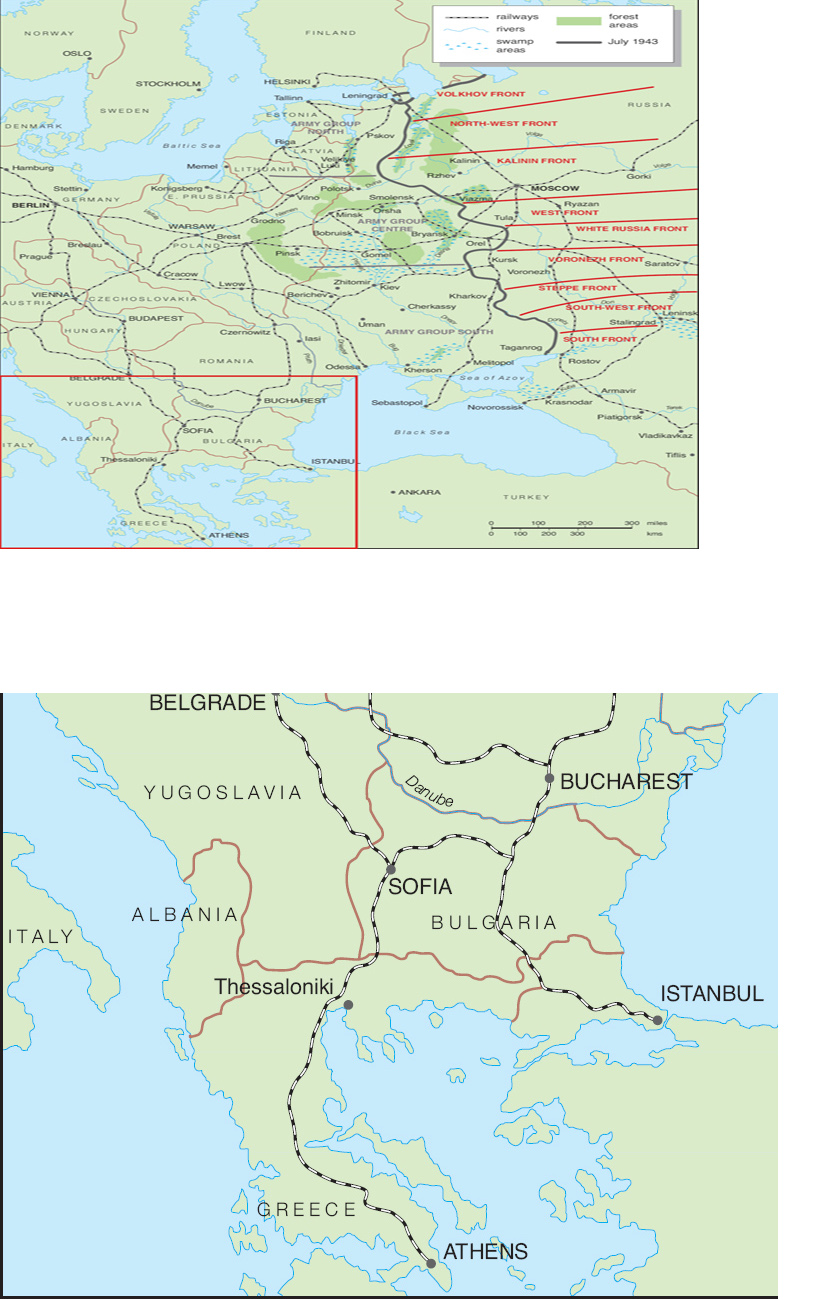

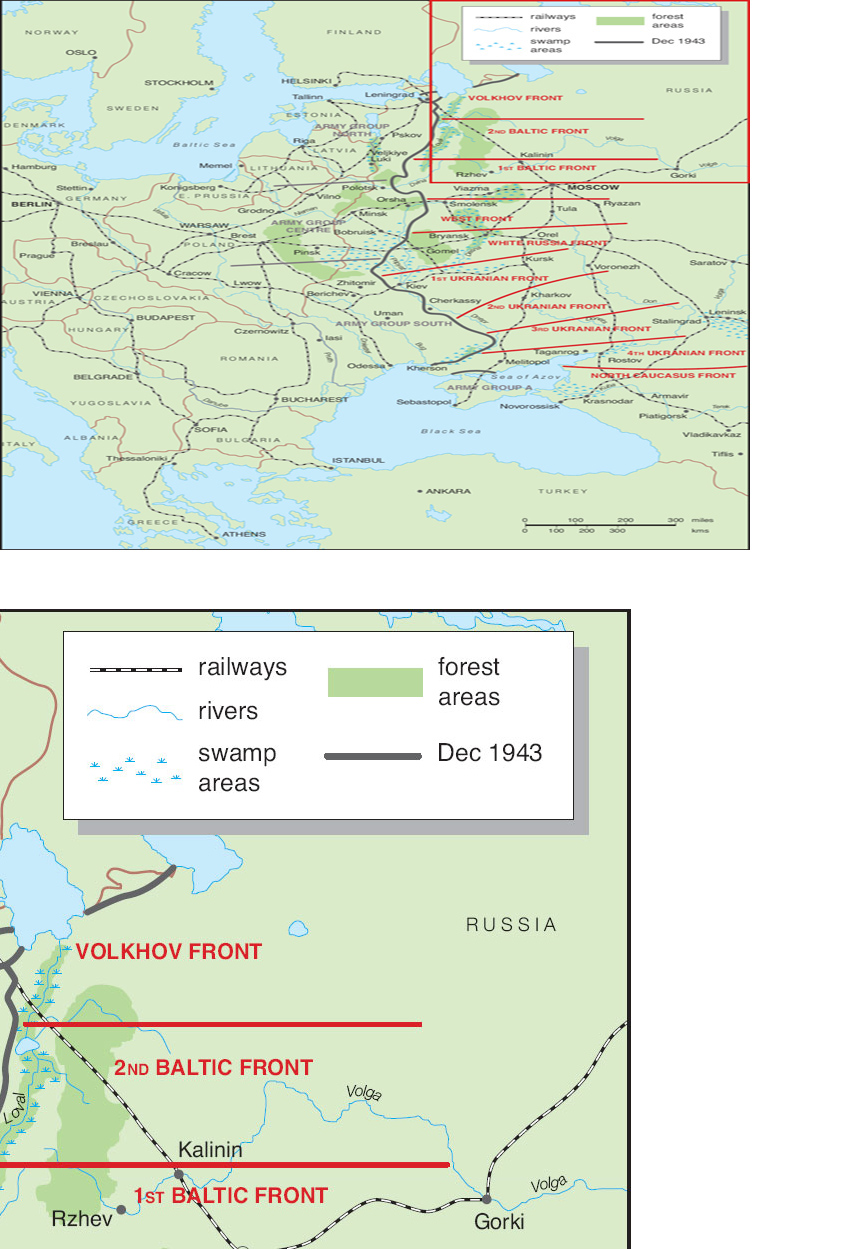

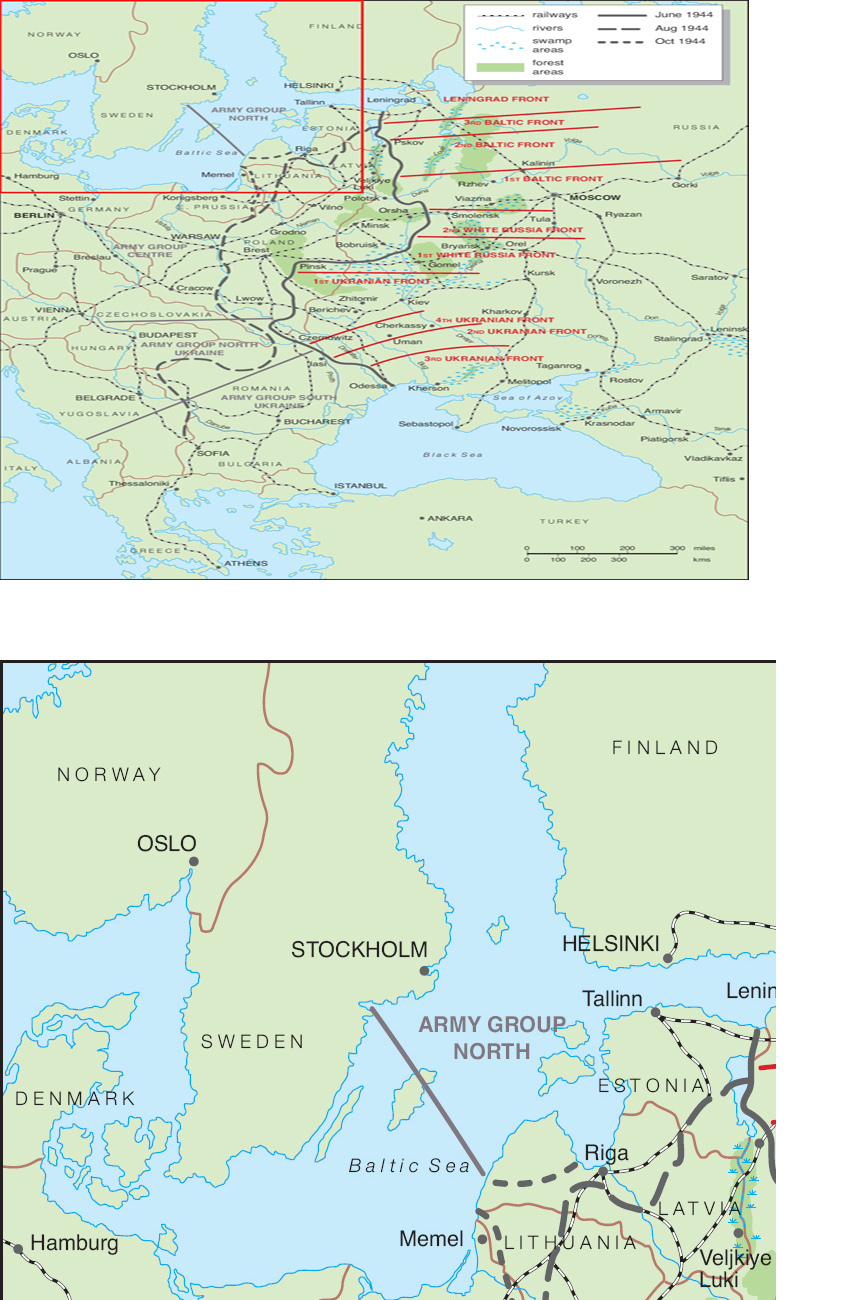

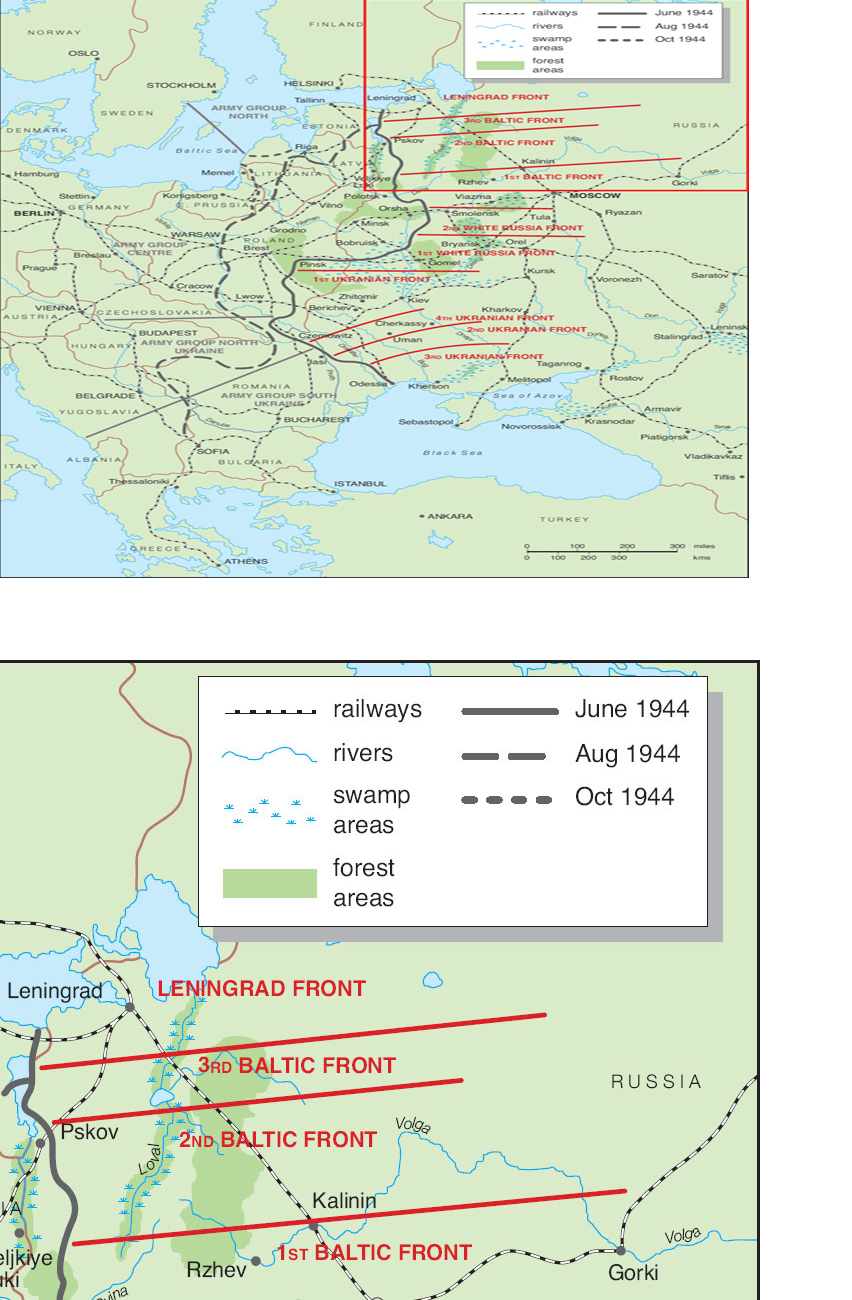

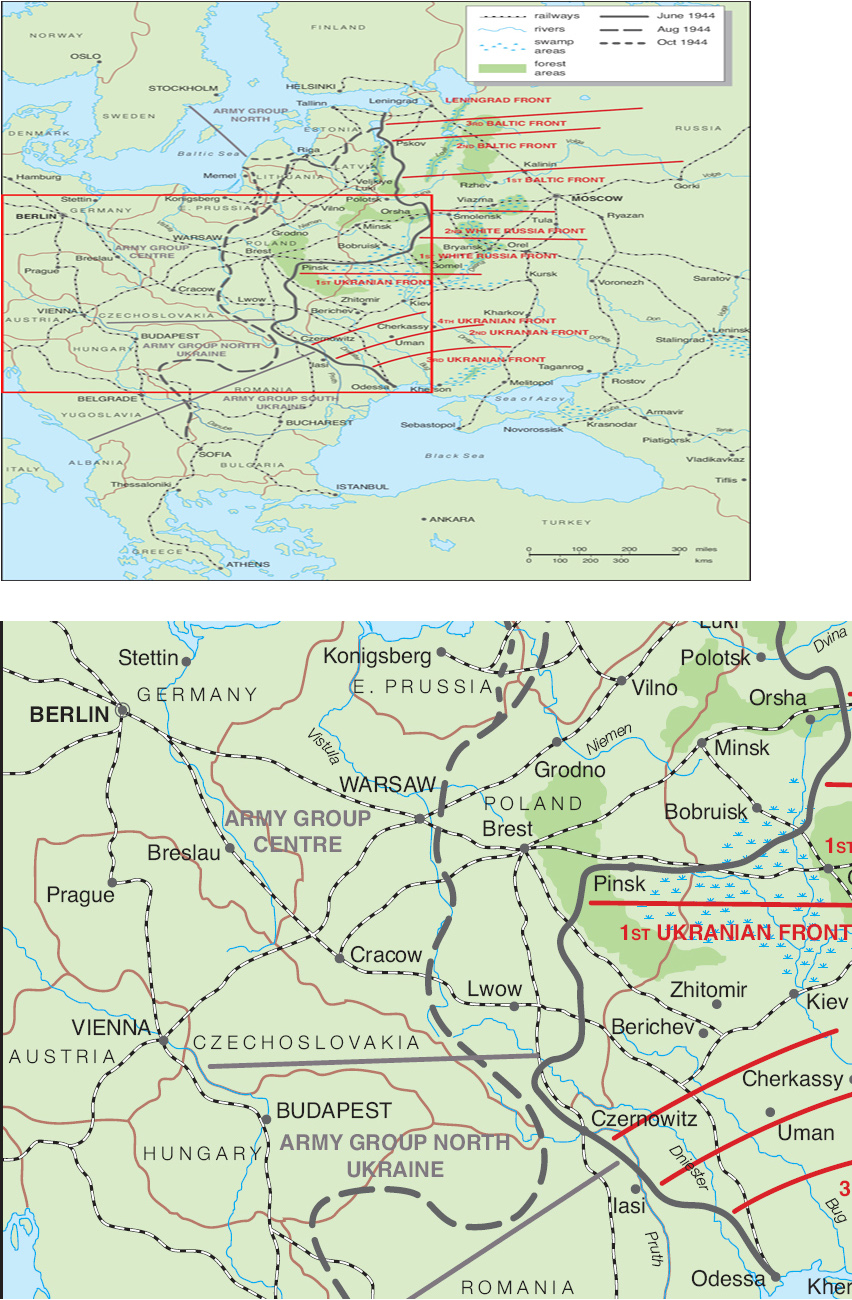

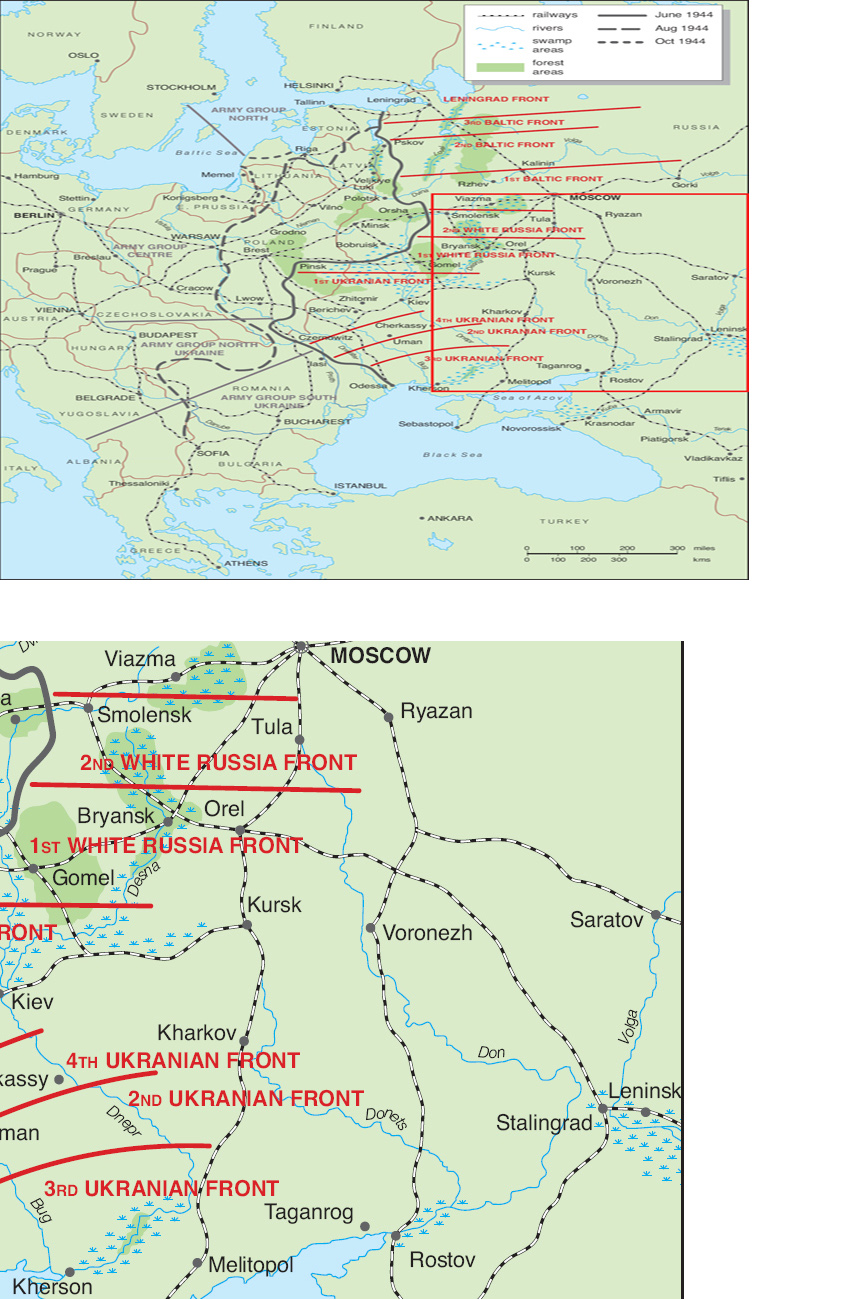

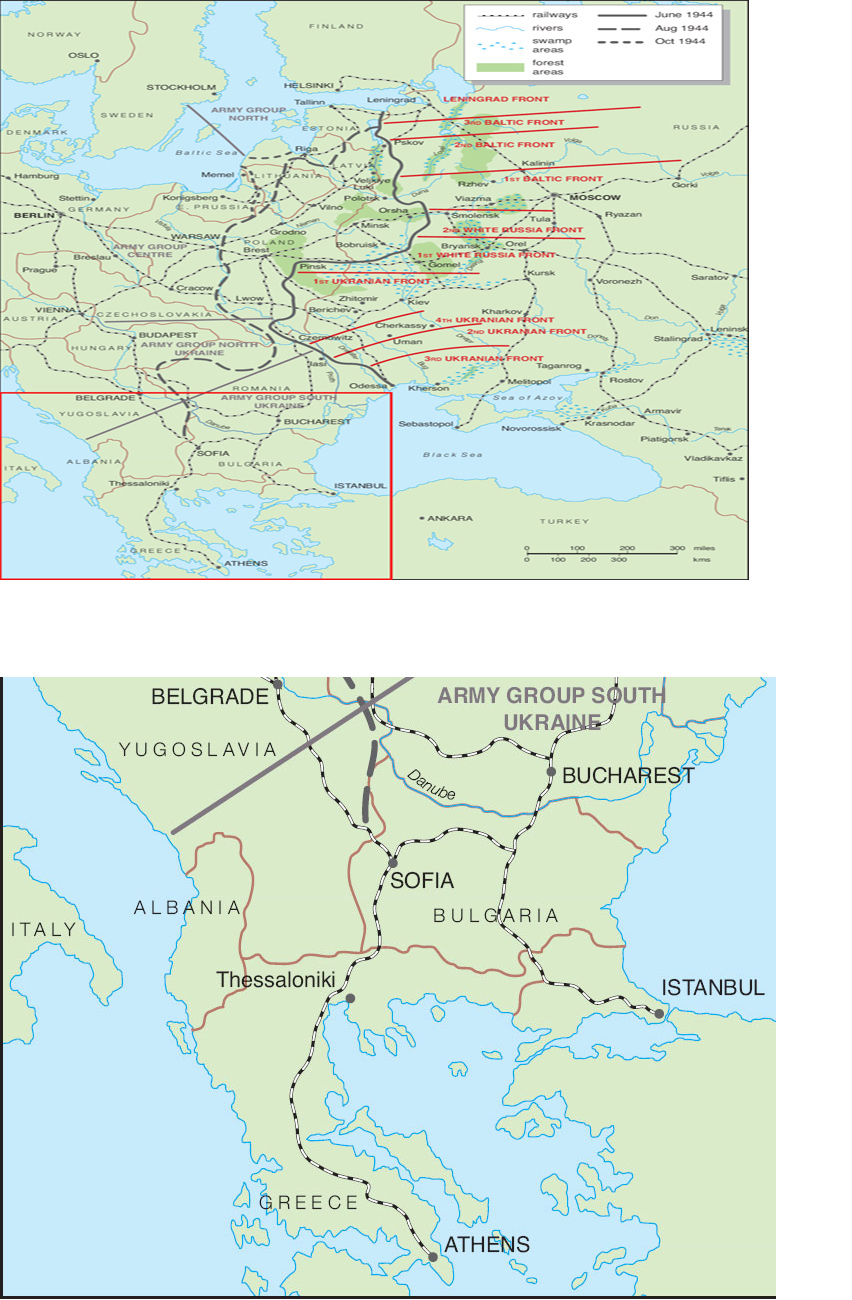

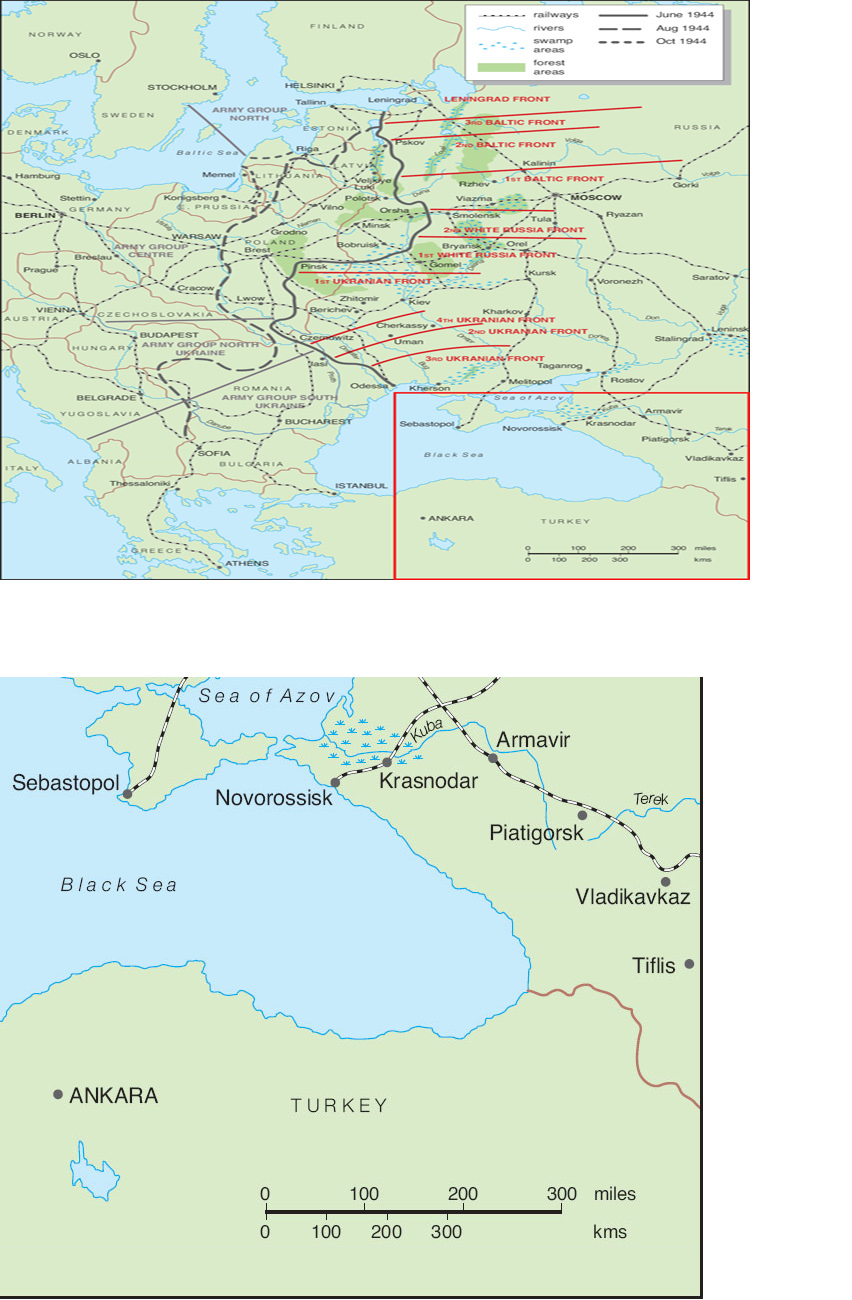

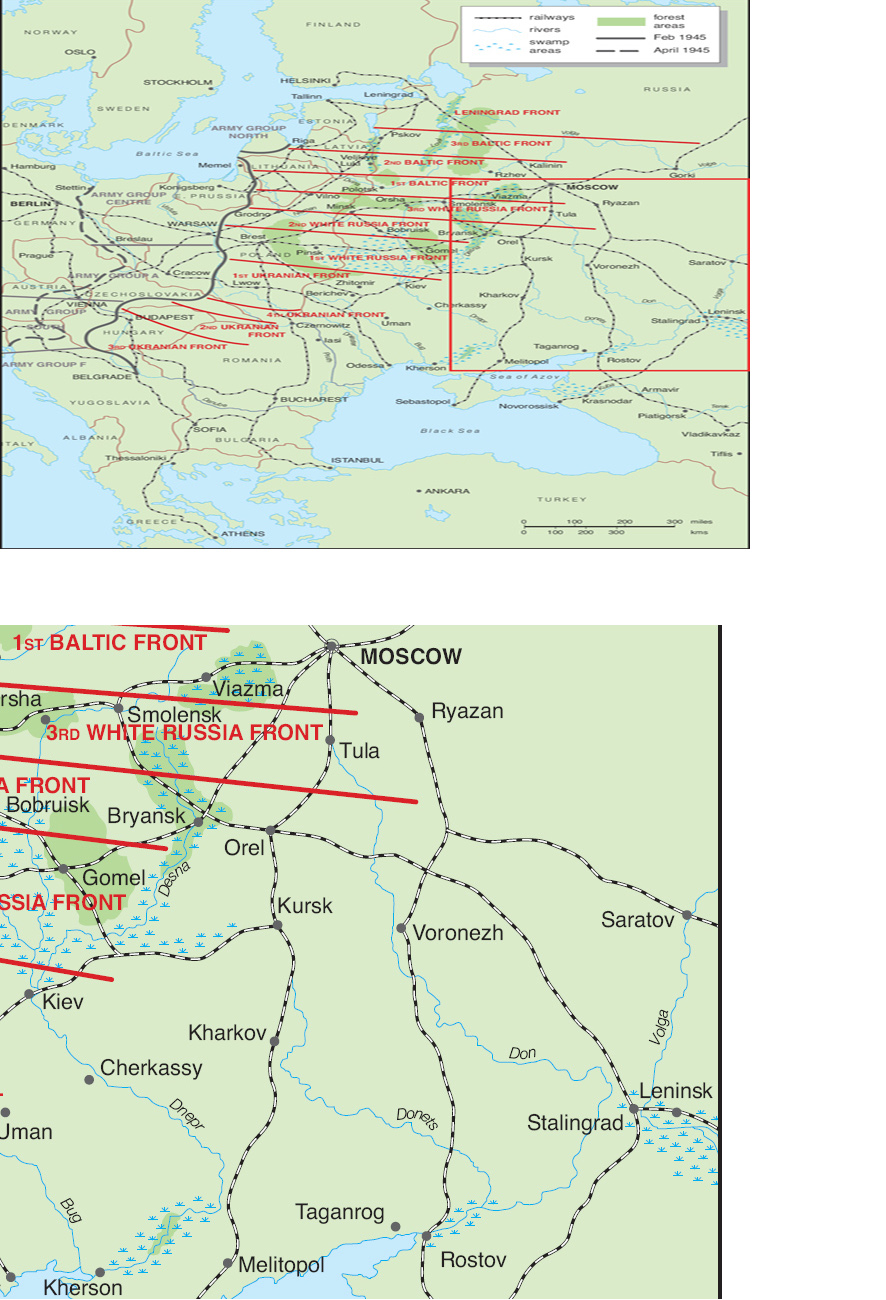

Hitler’s war against the Soviet Union led to the largest armies ever maintained fighting the greatest land battles yet seen. The front line would ultimately stretch for over 1,500 miles and at any one time there were close to ten million soldiers under arms. Note how the vast Pripyat marsh sits square in the path of an invader from the west. Partisan activity from 1942–44 would be concentrated in the swamps and forests shown here. Note also the pivotal importance of Moscow as the hub of the Soviet rail network.

The initial pace of the German advance exceeded their wildest expectations. By August it even seemed possible that Russia might be beaten in eight weeks, as Hitler had predicted. The Baltic States and Belorussia fell quickly, the Ukraine next, and over a million Soviet troops were taken prisoner. Yet by the time the German advance ground to a halt outside Moscow, the German Army had suffered 750,000 casualties.

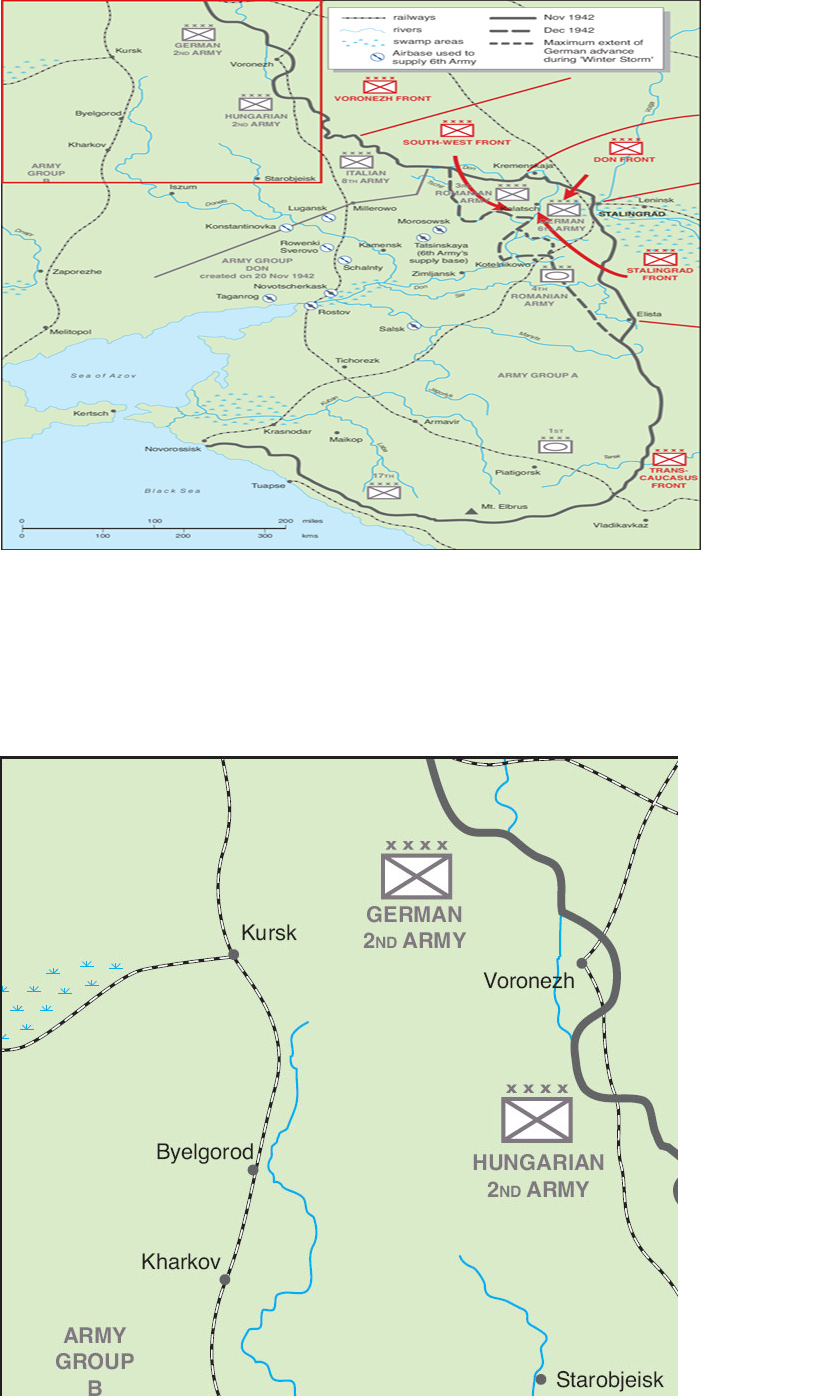

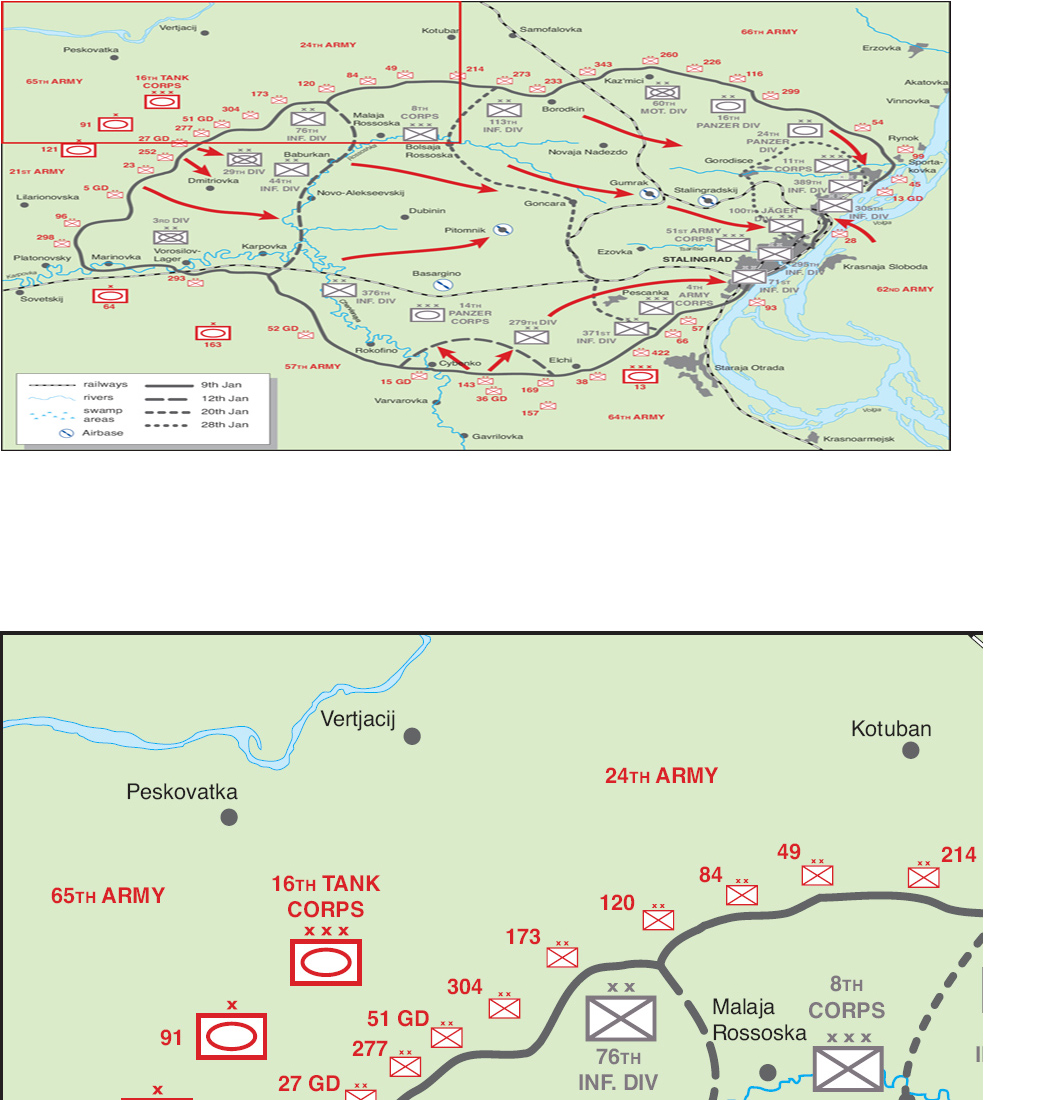

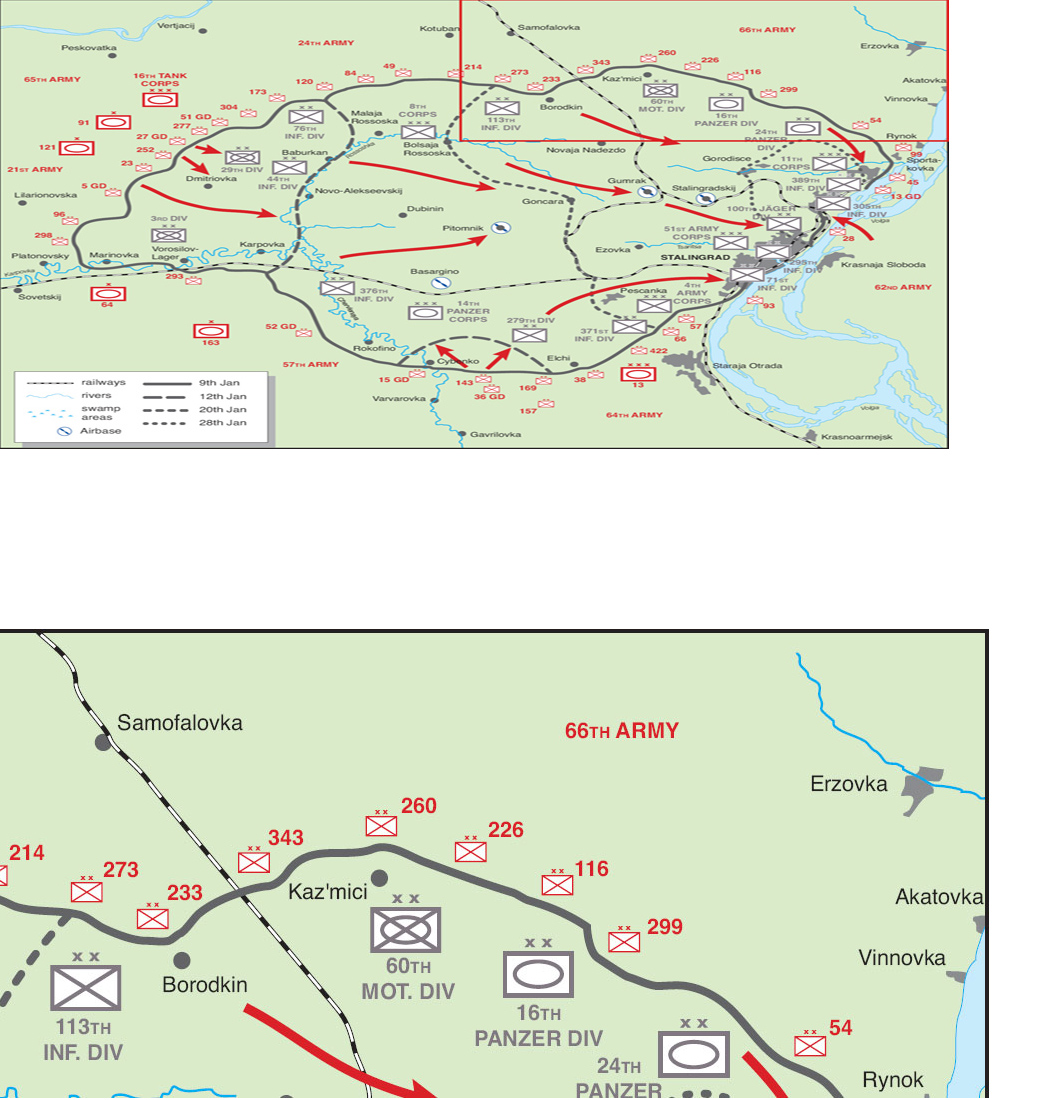

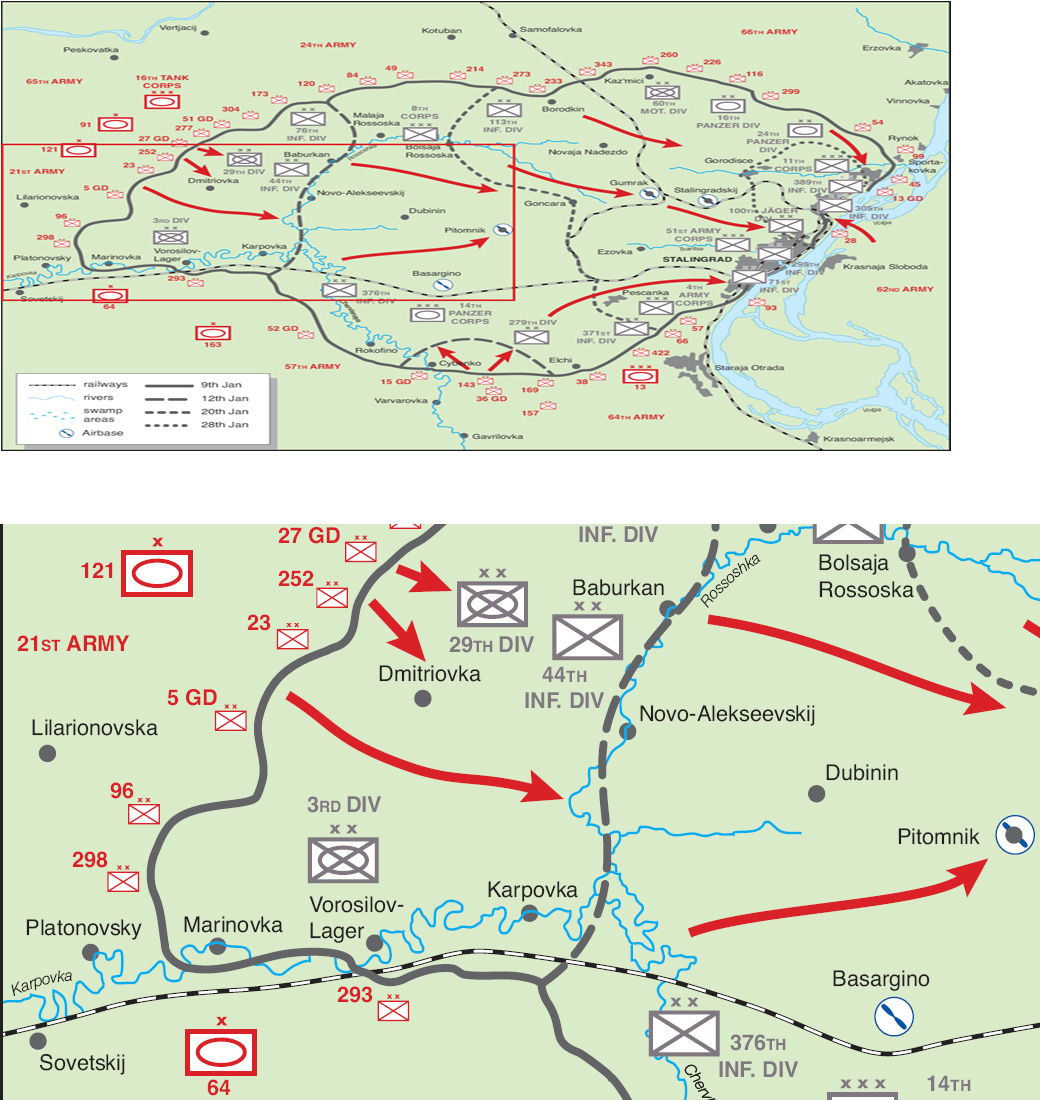

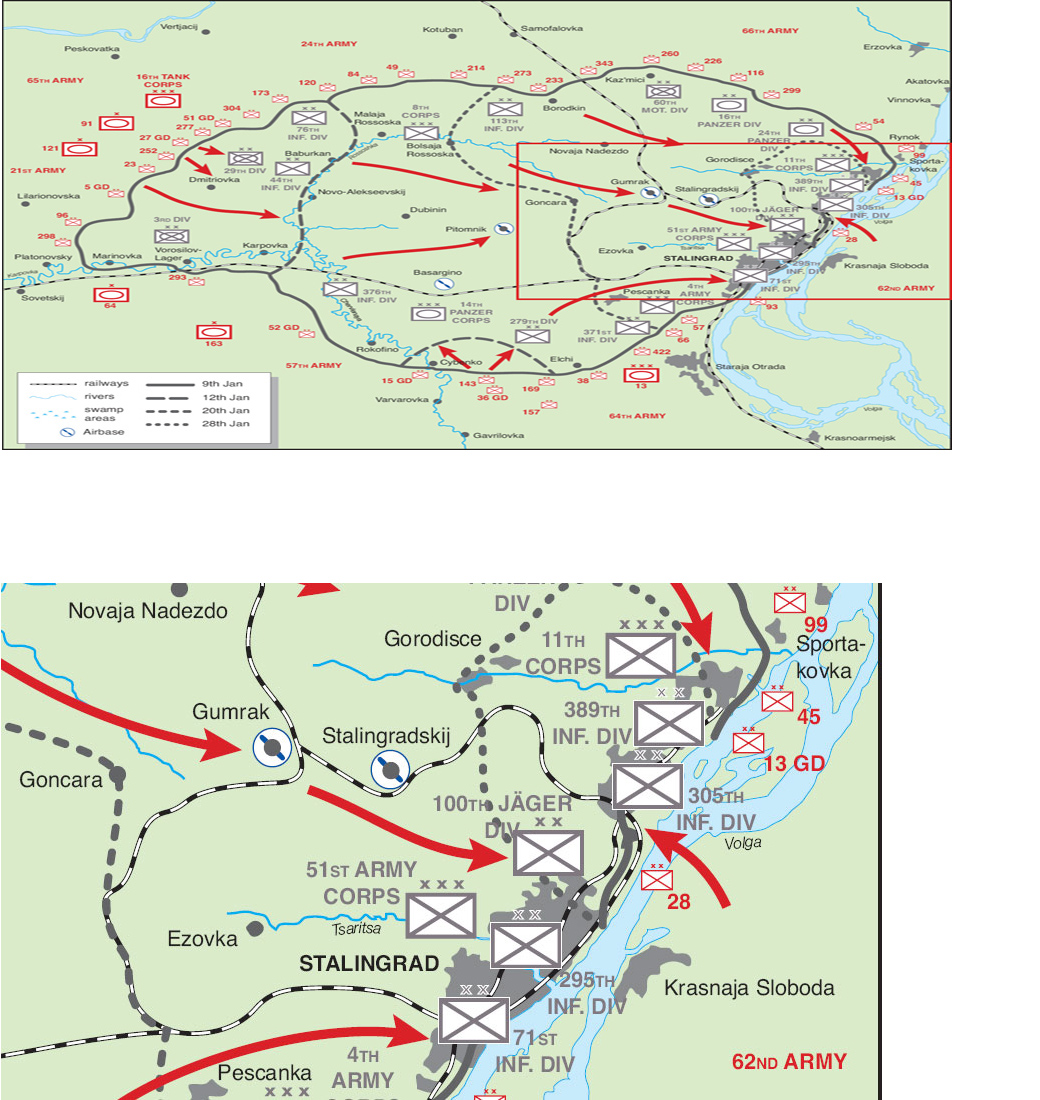

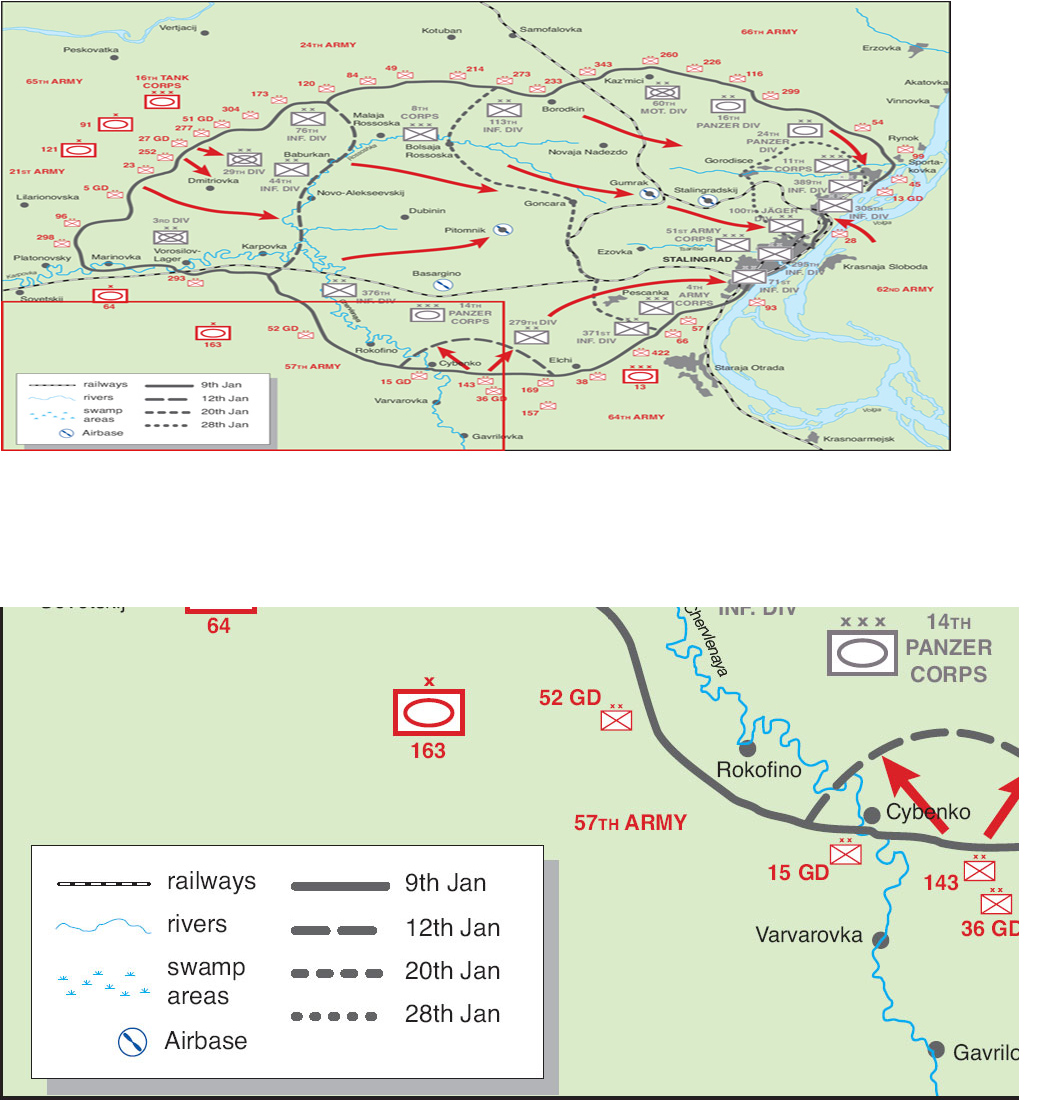

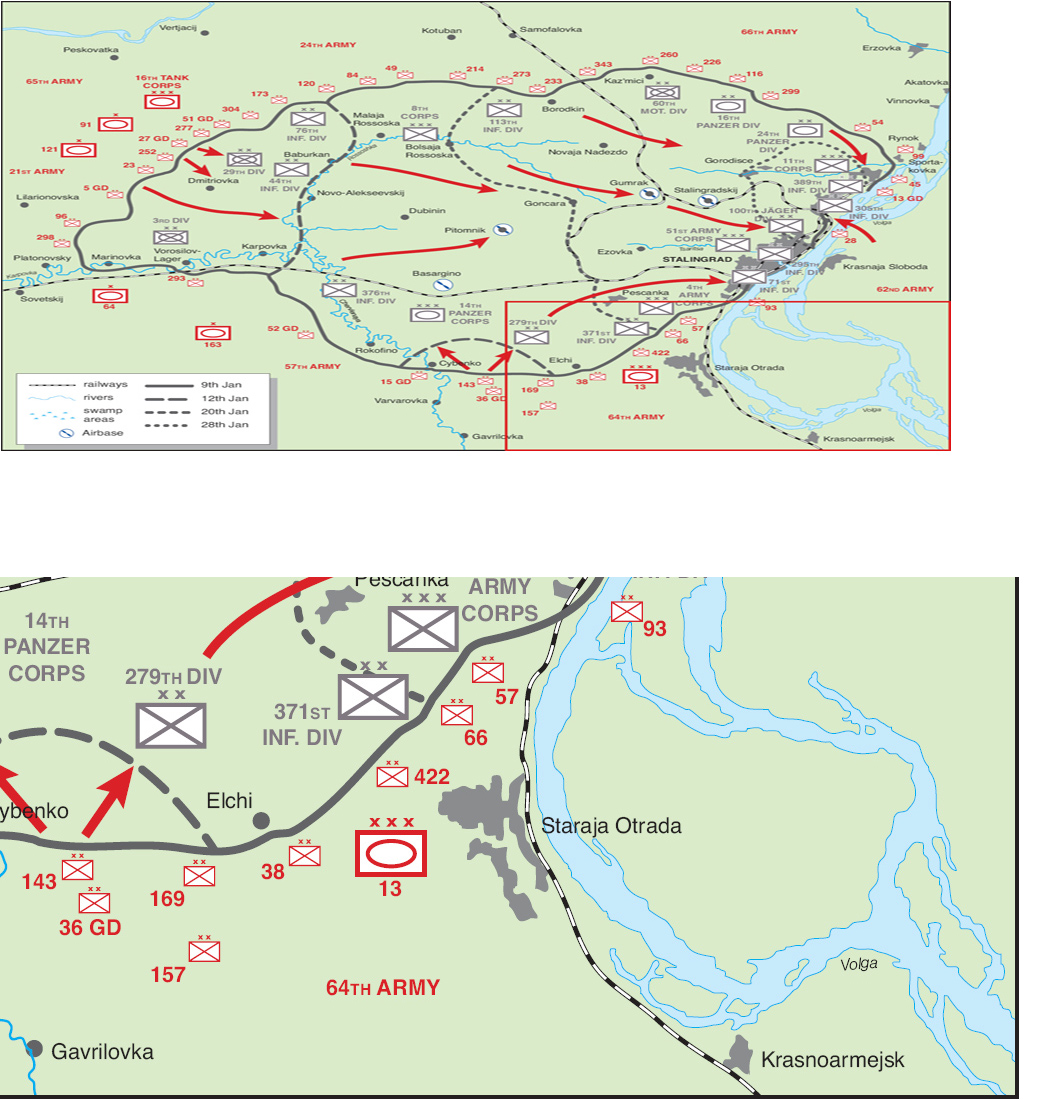

With German Panzer divisions scattered from the Moscow front to the Caucasus, the 6th Army was obliged to assault Stalingrad frontally, rather than envelop it in the traditional manner. By late 1942 the battle for the city had absorbed almost all the German units in the sector, the long flanks guarded by less well-equipped and less committed allied armies. The Soviet plan had worked.

Called a ‘fortress’ by the German High Command, the defences of Stalingrad consisted of a line of dug-outs across the bleak steppe. The Soviets found the defenders able to conduct sharp counterattacks as late as January, but the starvation diet and lack of ammunition led to a rapid collapse once the surrender offer was rejected.

Both sides attacked in 1943. The Soviets followed up their victory at Stalingrad by pressing as far west as Kharkov, but the city was retaken during Von Manstein’s celebrated counter-attack in February. The German generals then planned to attack the salient around Kursk, but the operation was delayed until July. Marshal Zhukov banked on stopping the German assault, then launching offensives of his own both north and south.

The battle of Kursk did not destroy the German armoured forces as is often alleged. Losses were far heavier during the long retreat across the Ukraine in the autumn, with large numbers of vehicles abandoned in the mud. The Soviet advance reached as far as Zhitomir before Von Manstein’s counter-attacks drove them back again, but the recapture of Kiev proved impossible.

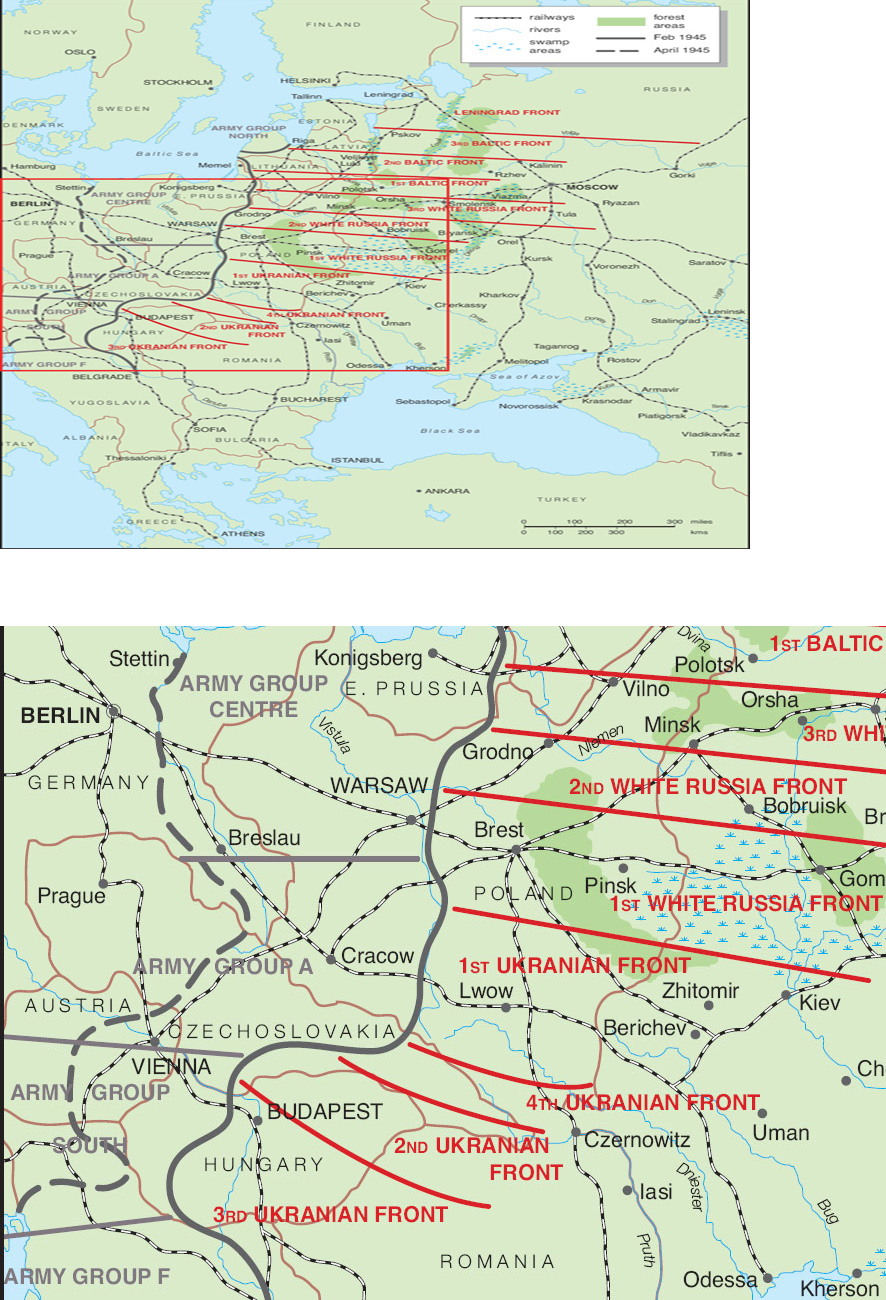

Soviet forces swept across the Western Ukraine, encountering resistance not just from the Germans, but from Ukrainian guerrillas, who in fact killed Marshal Vatutin. By the summer, the German Army Group Centre occupied a wide salient north of the Pripyat marshes. Soviet deception measures fooled the Germans into expecting another assault in the south, and the stage was set for the greatest German defeat of the war.

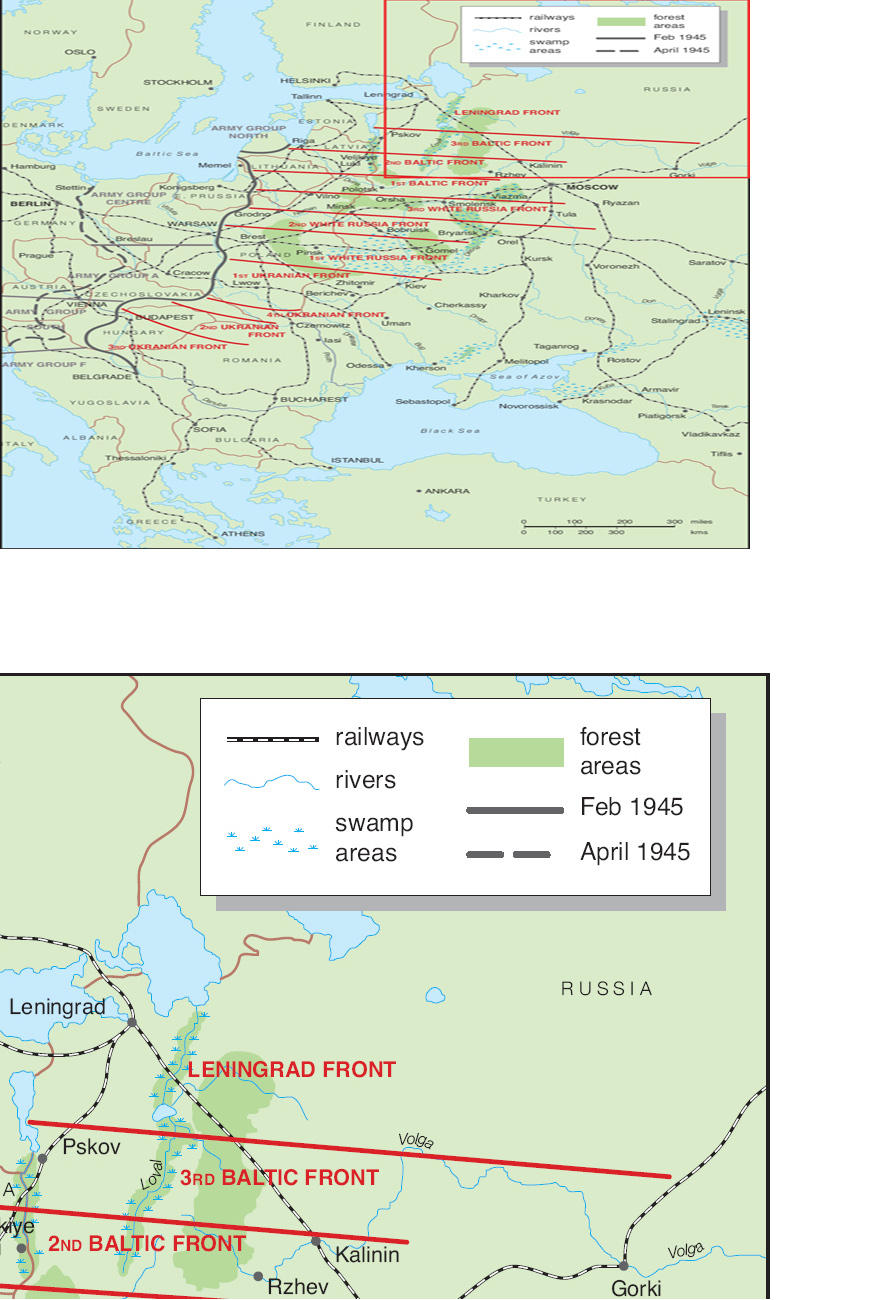

By the beginning of 1945 the Soviet Army was poised to conquer Germany. Hitler withdrew to a hastily prepared bunker in Berlin, still preaching victory. His generals began to ignore his orders, trying to hold back the Soviets at the cost of allowing the western Allies to overrun western Germany. By April the game was up and many German units broke contact with the Soviets to flee westwards in the hope of surrendering to the British or Americans.

On the morning of 18 May, 16th Panzer Division, divided into three Kampfgruppen, entered the suburbs of Iszum and cut the east–west highway that crossed the Donets at Donetsky. By 20 May the encirclement was all but complete; just a narrow neck of ground a few miles wide connected the three Russian armies with the rest of the South-Western Front. On 22 May, 14th Panzer Division beat off a series of Russian armoured counter-attacks to reach Bayrak on the Northern Donets; on the far bank lay the outposts of the 44th (‘Hoch-und-Deutschmeister’) Division.

Some 750,000 Red Army soldiers had taken part in the Kharkov offensive. By the end of May the battle had ended with the loss of one man in three. The encirclement and destruction of the 6th, 57th and 9th Armies struck 22 rifle and seven cavalry divisions from the Soviet order of battle, along with 14 tank and motorized brigades. Only scattered handfuls of men broke through the German cordon. David Glantz assesses Red Army losses at 170,000 killed, missing or captured, plus 106,000 wounded. Hardware losses were steep too: 650 tanks and 1,600 guns. Timoshenko was summoned to Moscow and he had good grounds for fearing for his life; in 1941 he had taken over from generals executed for defeats on a smaller scale. He was relieved of his command, but, as an old comrade from the Bolshevik 1st Cavalry Division, he retained his place in the Stavka and was sent to command the North-Western Front in July.

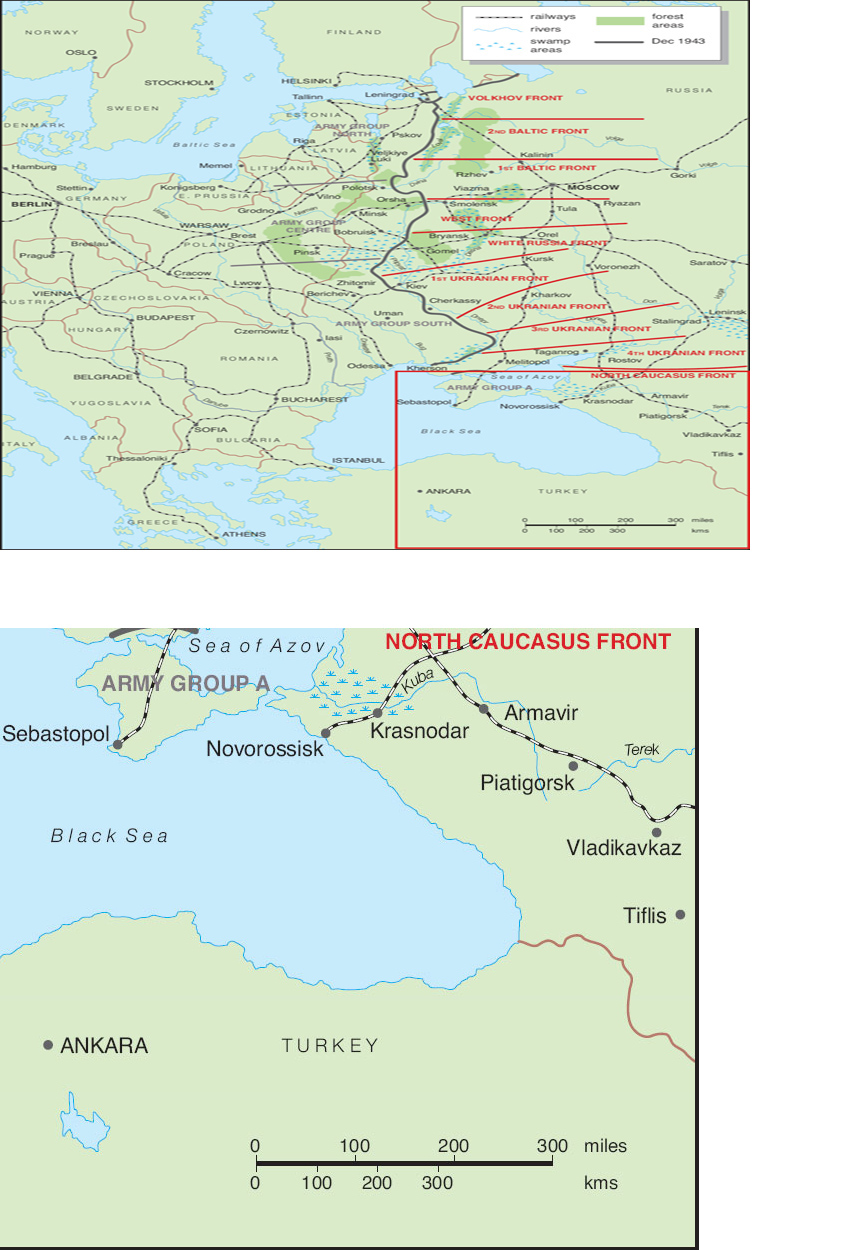

Just as the Kharkov offensive turned into a major disaster, so the Red Army lost its foothold on the Kertsch peninsula, and with it the only prospect of relieving Sebastopol. The traditional villain of the piece is Lazar Mekhlis, the Jewish Commissar assigned as Stavka representative to the Crimean Front. The head of the Main Political Administration of the Red Army and one of Stalin’s chief henchmen, Mekhlis had played a leading role in the purge of the army, and the survivors never forgave him. He was an abrasive bully whose working relationship with Lieutenant-General Dimitri Kozlov, commander of the Crimean Front, was bad from the start. Mekhlis sacked Kozlov’s highly competent chief of staff Fyodor Tolbukhin (a future Marshal of the USSR) and refused to permit any thought of defensive operations. He conducted an acrimonious correspondence with Kozlov and complained about him to Moscow. Having built a road across the frozen straits during the winter, the Russians had deployed three armies, the 44th, 47th and 51st – 260,000 men in 21 divisions – on the Kertsch peninsula by May 1942. They were supported by 350 tanks. However, attacks in March and April made little headway against Von Manstein’s 11th Army. Focused exclusively on his offensive, Mekhlis forbade any digging in, never thinking that his opponent might take the offensive himself.

Von Manstein’s army had had no armour when he broke into the Crimea in 1941. But Von Manstein’s infantry division had advanced almost as fast as the Panzers during the invasion of France in 1940, and his lightning strike towards Leningrad in 1941 had set new records for speed of manoeuvre. With additional Romanian units to screen Sebastopol, he transferred the bulk of his army east to clear the Kertsch peninsula again. It was not much of a bulk, just five German infantry divisions and 22nd Panzer Division. The 7th Romanian Corps (8th, 10th and 19th Infantry Divisions plus 10th Cavalry Division) made up the numbers, but their offensive value was ‘limited’, as Von Manstein diplomatically put it. The front line ran across the narrow neck of the peninsula centred on Parpach, 15 miles north-east of Feodosia. From an initial frontage of 15 miles, the peninsula widened to about 25 miles where the Soviets’ rearmost positions lay.

Air power tipped the odds. The whole of Baron von Richthofen’s Fliegerkorps 8 flew in support of Operation Trappenjagd (‘Bustard Hunt’) in which Von Manstein feinted in the north, where the Soviets had massed the bulk of their forces, then launched the 28th Light, 132nd and 50th Infantry and 22nd Panzer Division in a hook along the south coast. One battalion was landed by assault boats in the rear of the Soviet lines at Parpach on 8 May. Heavy but fake radio traffic in the north, followed by artillery barrages, helped induce Mekhlis to retain his reserves in the north. The infantry broke through, but it was not possible to exploit in depth with the armour until the following day. The Panzers beat off a Russian tank attack, but their continued advance was hampered by heavy rain, which also kept the Luftwaffe away from the battlefield. The weather cleared on the 11th, without the Russians showing any sign of reacting to the penetration of their front, and 22nd Panzer swung north to cut off about eight Russian divisions in their front line. Organized resistance collapsed and a scuttle to the rear began. Von Manstein’s pursuit was relentless and Kertsch fell on 16 May. The Stukas had a field day. The roads were jammed with abandoned or knocked-out vehicles: aerial photographs taken by the Germans are reminiscent of the ‘road of death’ on the highway outside Kuwait in 1991. Von Manstein drove past endless columns of prisoners to meet Richthofen on a hill overlooking the straits. The beach was equally crammed with Soviet tanks and transport. Russian torpedo boats tried to rescue their men from the shore, but German field batteries and repeated air attacks drove them off. Drum fire from Von Manstein’s corps artillery pulverized the last pockets of resistance and it was all over by 18 May.

Although some die-hards held out in caves for a few more weeks, the three Russian armies had ceased to exist. Five German infantry divisions and one of tanks, plus a pair of Romanian divisions, had annihilated more than 21 Russian divisions in a head-to-head fight. Von Manstein’s 11th Army recorded the capture of 170,000 prisoners-of-war, 1,133 artillery pieces and 258 tanks. Mekhlis was sacked, and also lost his job as Deputy People’s Commissar of Defence; Zhukov’s criticism was biting, but Mekhlis was Stalin’s creature and did not share the fate of his many victims. He remained a Commissar at front level throughout the war despite further clashes with senior army commanders and at least three formal censures for incompetence. Kozlov was posted to command a reserve army, but worked his way back to deputy front commander by the end of the year.

With the Kertsch bridgehead eliminated, the naval base of Sebastopol was isolated and doomed. The landward approaches were defended by giant concrete and steel fortifications, forts ‘Stalin’, ‘Molotov’, ‘Siberia’ and ‘Maxim Gorky’. Their heavy guns duelled with German artillery until a combination of gargantuan siege guns and constant air attack silenced them. The German siege train included the 60cm mortar ‘Karl’ and the 80cm calibre railway gun ‘Gustav’. The latter, the biggest gun ever built, was originally intended to breach the Czech Sudetenland and French Maginot Line defences. Its 7-ton armour-piercing shells destroyed a Soviet ammunition bunker under Severnaya Bay, passing through the water and 100 feet of rock before detonating inside the magazine. Its high explosive rounds weighed more than 10 tons and were used to pulverize one fort after another. Even then, it took teams of combat engineers with flame-throwers and grenades to storm the strongpoints, which were connected by underground tunnels. It was horribly reminiscent of the battle of Verdun in 1916, although Von Manstein took care to maximize the use of engineers, artillery and air power rather than squander his infantry.

The Luftwaffe flew some 23,000 sorties to deliver 20,529 tons of bombs on Sebastopol in three weeks. (By comparison, the Luftwaffe dropped 21,860 tons of bombs on the whole of the UK during the 1940–41 ‘Blitz’.) German artillery fired 562,944 rounds. The assault began on 7 June and by the end of the month it was clear that the end was near. Destroyers could enter the port by night, but the remorseless German advance brought their guns in line with the harbour. Submarines continued to deliver ammunition and take off a lucky few of the wounded, but the bulk of the garrison fought and died in the ruined forts, bunkers and rubble of their city. The last centres of resistance were overwhelmed in early July and 90,000 men went into captivity. Von Manstein was promoted to field marshal by a delighted Führer. His opponent, General Ivan Petrov, was reckoned to have done a good job holding on as long as he did, and was evacuated; he was made a Hero of the Soviet Union in 1945. Of the approximately 30,000 civilians left in Sebastopol, two-thirds were deported or executed.

The Crimean campaign cost the Red Army grievously. Modern estimates suggest that the Russians lost about 150,000 men in Sebastopol and another 240,000 in the Kertsch peninsula disaster. The decision to hold the fortress to the last and to attempt its relief in the winter of 1941–42 made sense if it tied down substantial German forces, but Von Manstein was given a rather minimal force for such an undertaking. If his divisions could have been more usefully employed elsewhere, then the same argument applies even more strongly for the Red Army. The reckless expenditure of manpower in the Crimea left them with little in reserve in the summer of 1942.

As the guns fell silent at Sebastopol, Hitler moved his headquarters to Vinnitsa in the Ukraine to oversee a new and enormously ambitious offensive. Although some of his senior commanders, most notably the navy commander-in-chief Admiral Raeder, argued that Germany should remain on the defensive in Russia while attacking in the Mediterranean, Hitler’s attention was focused almost exclusively on the east. That he would continue to concentrate on the Russian front, and site his headquarters in East Prussia until the end of 1944, demonstrates its overriding importance to him. It also exposes the limits of his horizons. In what was now a global war involving four continents, Hitler remained obsessed with the Eastern Front and would attempt to micromanage the campaign there, while critical events in other theatres passed him by.

Stalin’s hopelessly premature offensives cost the Red Army approximately 1.4 million casualties between January and June 1942. German losses were around 190,000, or less than one-seventh of the Soviet total. Stalin and his generals had very little to show for this enormous squandering of life. Great stretches of the front line remained pretty well where it had been established in December 1941. Even where the Ostheer had been compelled to pull back, at Rostov in the far south and opposite Moscow, it had only given up a maximum of 150 miles. The conventional view is that the winter campaign left the German Army clinging to its lines, but sensing it had bitten off more than it could chew; that the failure to capture Moscow – and win the war at a stroke – made ultimate defeat inevitable. This is open to challenge. The Red Army, so badly smashed in 1941, was in a desperate plight at the beginning of 1942 and lacked the competence at every level to take on the Germans in major operations. Its regiments were filled with half-trained conscripts, commanded by junior officers who were largely making it up as they went along, and all were terrified of making a mistake that could result in their arrest. The Red Army’s failure in these circumstances was to be expected. The surprise is the sheer scale of the disparity between Russian and German casualties in the first half of 1942. In this grisly battle of attrition, Germany was actually winning.

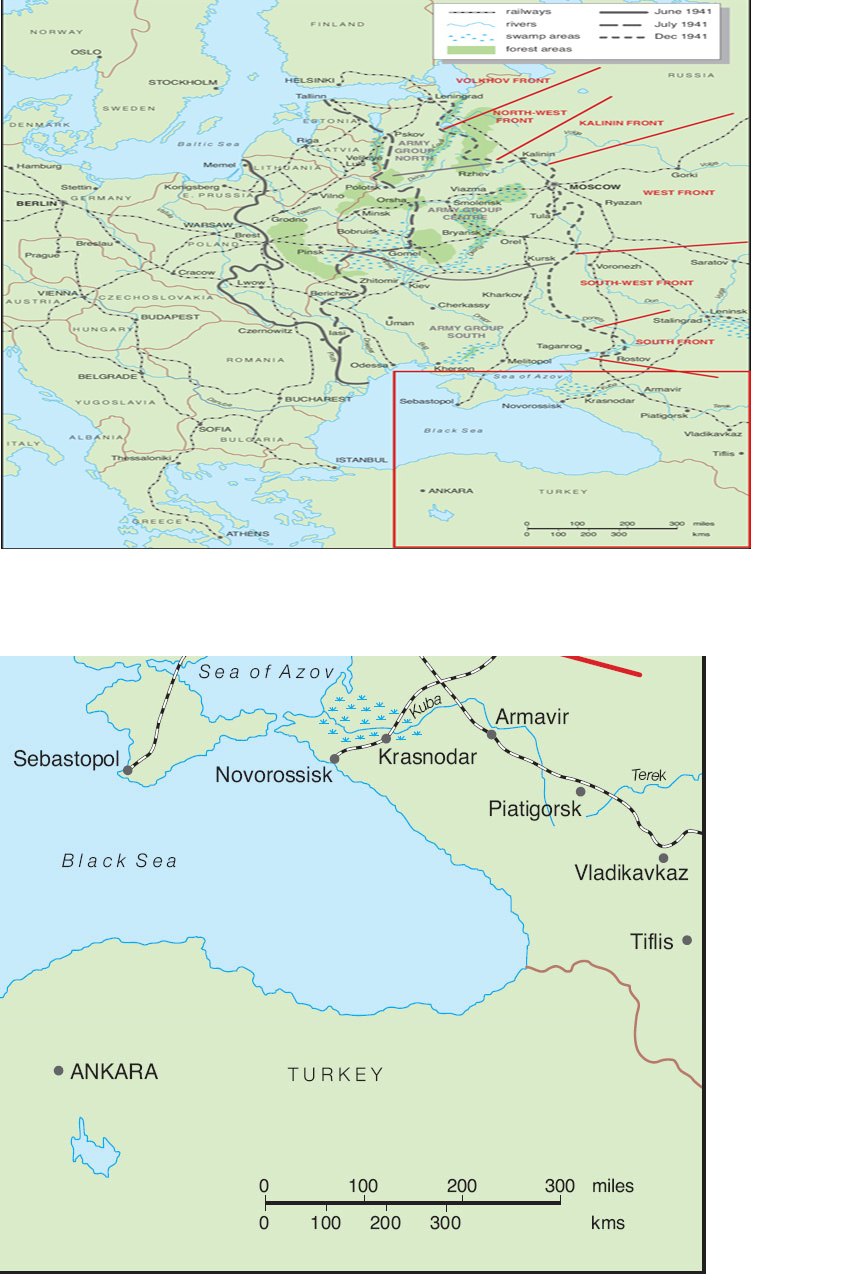

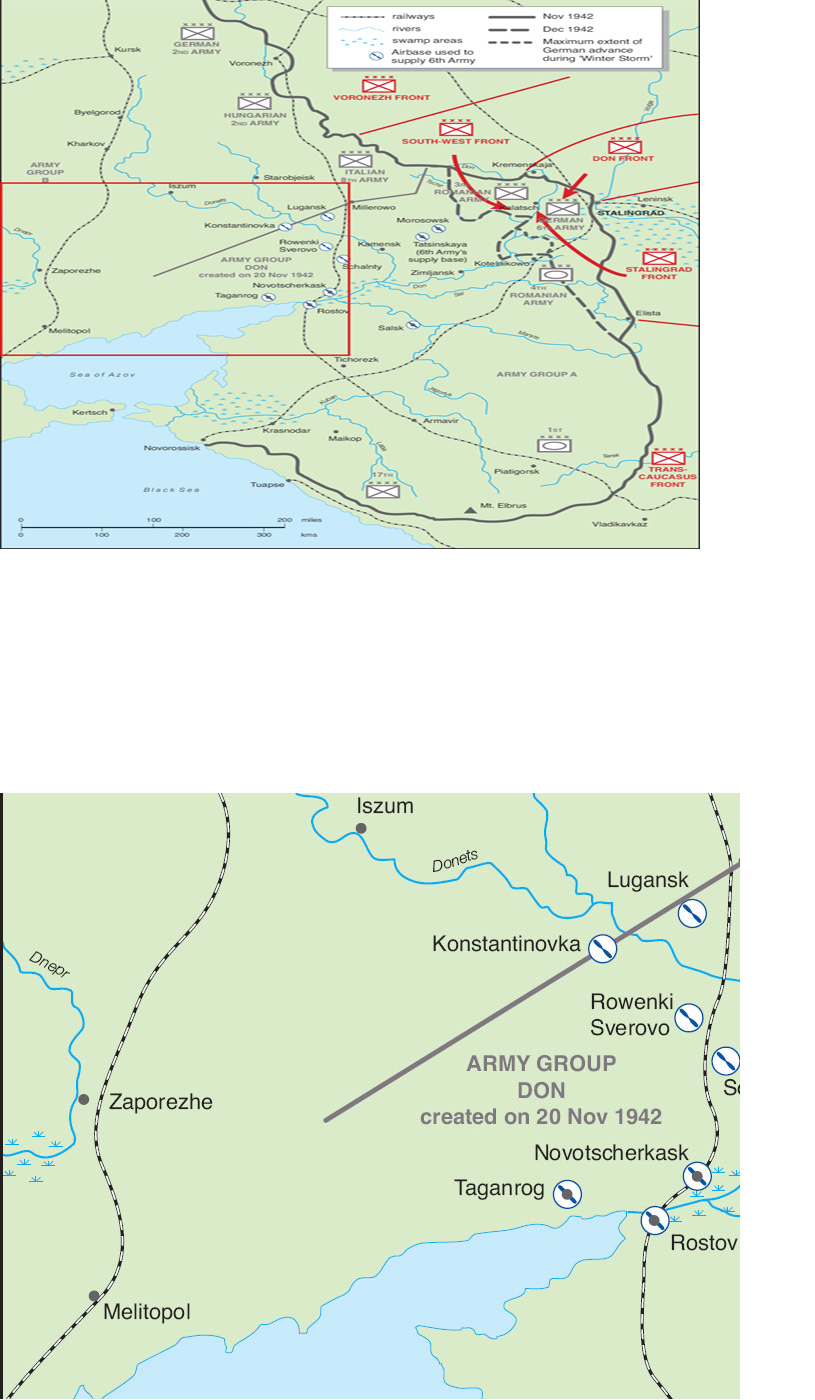

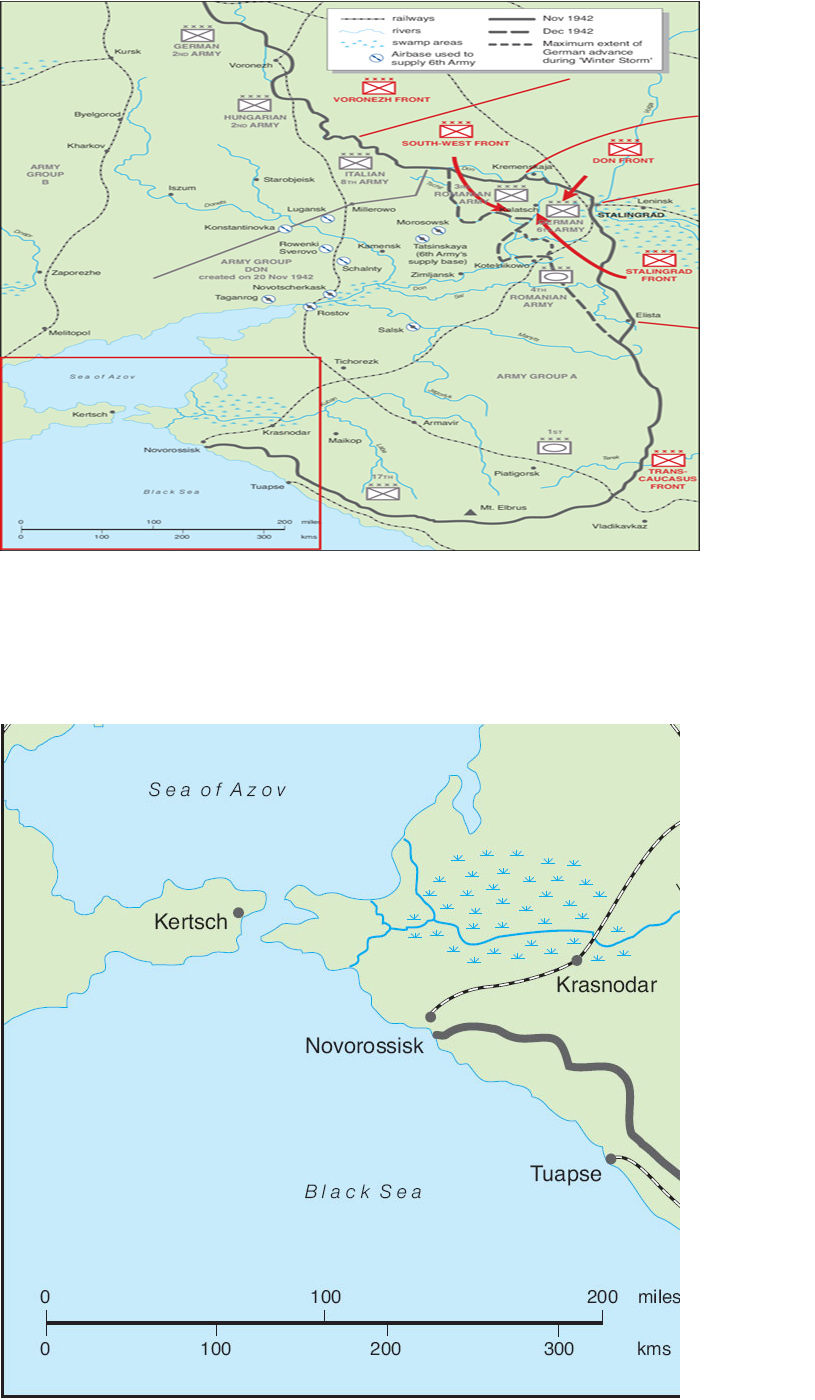

Hitler’s target in 1942 was the Soviet oil industry. By seizing the oil fields of the Caucasus he intended to solve the oil shortage that bedevilled the German war machine, and deprive the USSR of its main source of fuel. The German Army would strike past the junction of the Don and Donets, seizing Rostov on one flank and Stalingrad on the other. The Volga was a vital waterway for the USSR, and the occupation of Stalingrad would block another logistic artery.

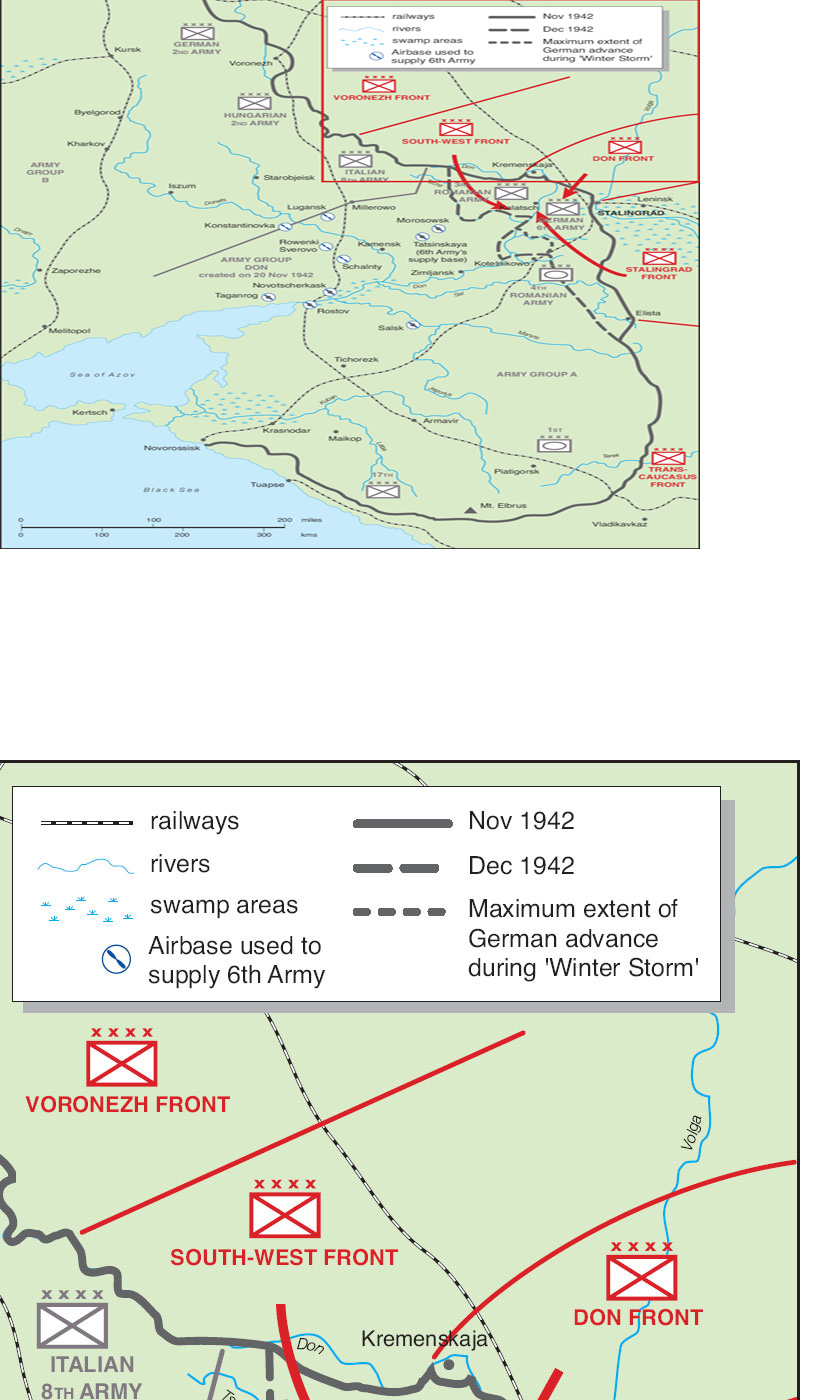

The shores of the Caspian sea lay 400 miles south-east of the front line. But to undertake this dramatic advance, the German Army had less than half the forces available in 1941. A total of 68 divisions, including eight Panzer and seven motorized divisions, would take part in the offensive. Army Group Centre retained the balance of German armour, but its divisions were at very reduced strength. The SS motorized divisions ‘Leibstandarte’, ‘Das Reich’ and ‘Totenkopf’ were withdrawn to France during 1942 to refit as Panzer divisions, reappearing to dramatic effect in February 1943. The absence of an armoured reserve in late 1942 would prove critical. Across the whole front, 3.25 million German soldiers faced a Red Army calculated by German intelligence at five million strong. In fact, its strength was closer to six million.6 While the Soviet mobilization had conjured up 488 divisions in 1941 and would create another 134 during 1942, the German Army had no reserve other than its garrisons in western Europe. To bulk out the numbers, Hitler pressured his allies into contributing nearly three-quarters of a million personnel.

Germany’s allied forces varied in motivation, training and equipment, but all were notably inferior to regular German soldiers. Such reliance on second-rate troops, who could not be replaced, reveals just how Hitler had raised the stakes. This was an ‘all or nothing’ strategy. The Romanians had already contributed heavily, suffering some 98,000 casualties in the battle for Odessa in 1941. This expended the best of their peacetime-trained formations and a terribly high proportion of their officers. For the 1942 campaign they deployed no fewer than 24 divisions, a maximum effort they could not repeat. The Italian expeditionary force of three divisions sent to Russia in 1941 had suffered badly in the winter, lacking cold weather clothing and equipment. Nevertheless, Mussolini expanded it to become the Italian 8th Army: ten divisions with a total strength of 229,000 men and 1,100 guns in April 1942. An infantry corps and an Alpine corps (with its supply column of 20,000 mules) were added during the summer, the latter earmarked for the Caucasus Mountains. Hungary was pressured too, and its divisions reinforced its rather token contribution to Hitler’s war of conquest to make a full army of ten divisions (2nd Army). Even Slovakia dispatched fresh troops – its motorized division would end the year very far from home, on the Kalmyk steppe with Panzergruppe Kleist. This was the first and only year of the war in which Germany’s allies made a significant numerical contribution to the Russian front. By January 1943 most of these men would be dead or in Soviet prison camps.

The Luftwaffe concentrated almost its entire strength on the Eastern Front for the summer campaign. Against a Soviet air arm that was reduced to 5,000 aircraft and unable to seriously interrupt German aerial missions, the Luftwaffe had a total of more than 4,000 aircraft of which about 3,000 were deployed to Russia. In June 1942 the Luftwaffe had the following aircraft on the Russian front: 1,237 bombers, 369 dive-bombers, 278 Me-110 twin-engine fighters, 1,253 Me-109 fighters, 486 recce aircraft, 529 transports and 112 sea planes.

The original German plan called for Army Group South to be divided into two army groups (A and B) after Hitler sacked Von Bock for the second time on 15 July. (He had been restored to command in early 1942.) Army Group B, commanded by the 62-year-old former cavalryman General Maximilian von Weichs, was to advance into the bend of the Don River, then drive on Stalingrad as one half of the traditional pincer movement. Army Group A, led by Field Marshal Wilhelm List, comprising 1st Panzer Army, 17th German and 3rd Romanian Armies, would form the other pincer. List was ordered to take Rostov before linking up with Army Group B in another battle of encirclement on the approaches to Stalingrad. With the Red Army driven back to the Volga, hopefully with heavy losses, Army Group A would then swing south and east to occupy the Caucasus oil fields. Dividing Army Group South into two was all very well if they could coordinate their actions but, as usual with the Nazi command structure, so much had to be referred back to Hitler. There was little liaison between the different German army groups, and the division of Army Group South into two was a recipe for confusion. Had Von Bock remained in charge of a united Army Group South, the subsequent disaster would probably not have been on quite such a drastic scale.7

July saw such rapid German advances that the Soviet official history tried to explain this as a deliberate strategy to draw the Germans on to defeat. The fact that future premier Khruschev was Chief Commissar of the South-Western Front, and that the commander of the Southern Front was later his Minister of Defence, may not be unconnected with this. However, like many other ‘feigned retreats’ in history, this was nothing of the sort. The South-Western Front (Timoshenko) and Southern Front (Malinovsky) had 1.3 million men in 68 divisions and six tank corps. They also had a copy of the German plan for Fall Blau (Operation Blue), recovered from a crashed German aircraft on 20 June. Nevertheless, they retained large forces in the Don bend on the line of the Rivers Tschir and Tsimla as the German spearheads, delayed by petrol shortages, approached.

Paulus’s 6th Army succeeded in trapping the Russian 62nd Army and 1st Tank Army in a double envelopment, crossing the Don behind the Soviet forces. Timoshenko’s and Malinovsky’s Fronts both collapsed with catastrophic losses, possibly more than 350,000 or twice as many as thrown away in the Kharkov débâcle earlier in the year. More than 2,000 tanks were lost too. There would have been many more prisoners if the Germans had not run out of petrol; they had only ten Panzer or motorized divisions operating across a frontage of 400 miles.

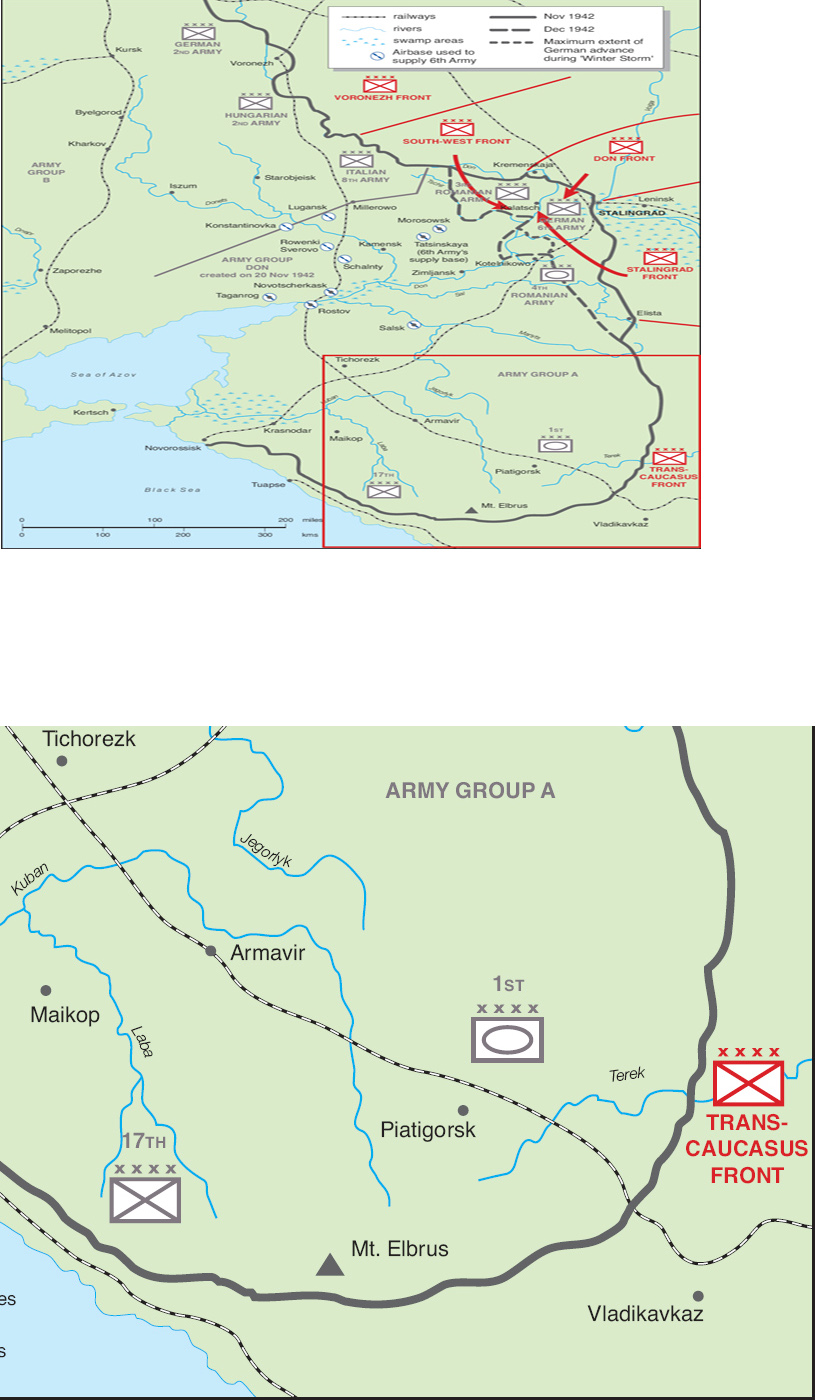

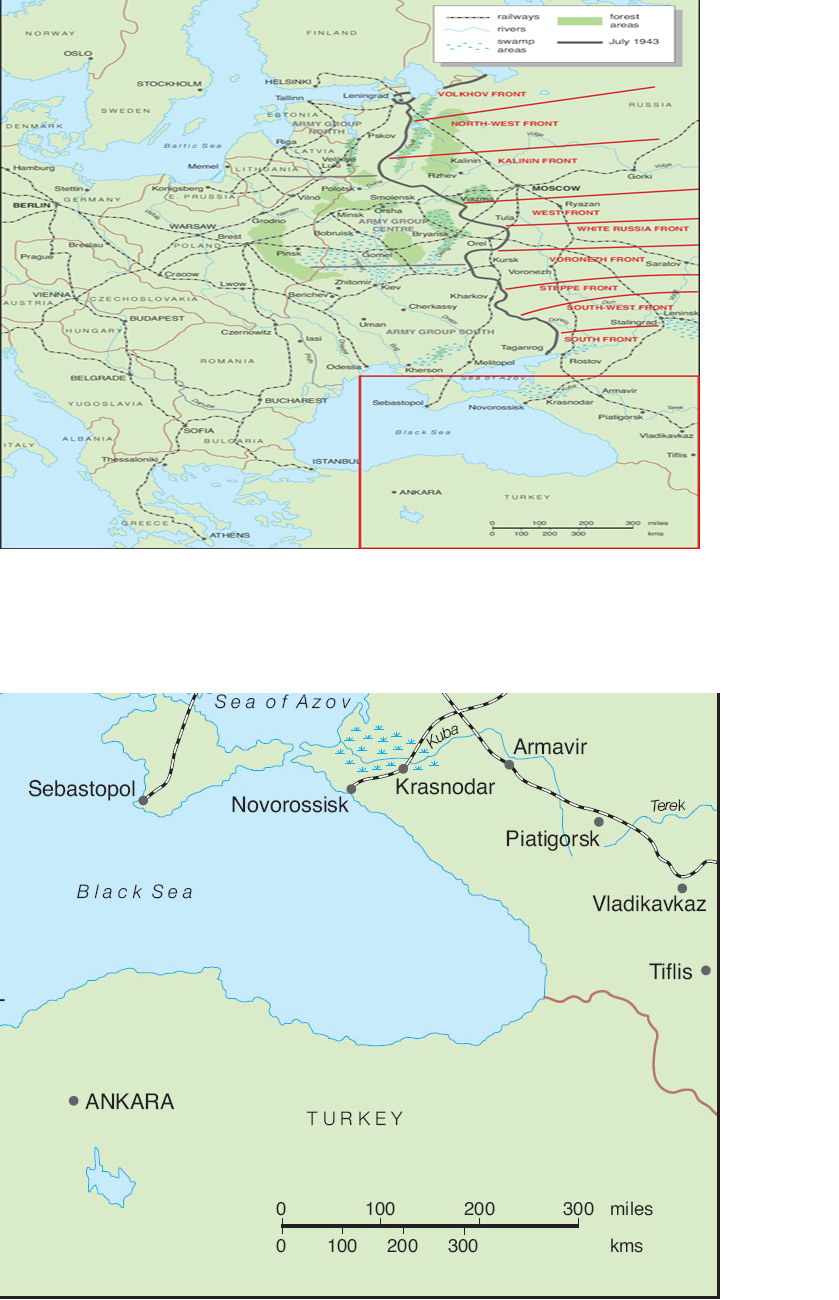

One minor Russian success went unnoticed in the shadow of this catastrophe, but was to have great importance in November. Russian troops managed to cling to a small bridgehead on the west bank of the Don, south of Kremensk. Meanwhile, on the Central Front where Stalin had expected the blow to fall, Zhukov launched an offensive north of Orel, inflicting heavy casualties on 2nd Panzer Army. The impatient Führer ordered Army Group A to take Rostov and advance along the eastern coast of the Black Sea while Army Group B was to detach 1st and 4th Panzer Armies. While this armoured force struck at Maikop, Grozny and Baku, the rest of Army Group B continued towards the Volga. The speed of the Russian collapse in the south arguably helped the Red Army in the long run since it encouraged Hitler in his belief that he could capture both Stalingrad and the Caucasus at the same time. Tougher resistance might possibly have allowed saner counsels to prevail and led to the Germans settling for more achievable objectives.

The 4th Panzer Army was soon returned to Army Group B, supporting the German 6th Army, which reached the outer suburbs of Stalingrad on 23 August. The honour of breaking into the city fell to the 79th Panzergrenadier Regiment, which captured the northerly suburb of Spartanovka just before midnight. Hitler’s army had reached the Volga.

Had 4th Panzer remained with 6th Army in July, it might well have been able to seize the city then, but by the beginning of September it was clear the Russians were determined to hold Stalingrad. Unlike the previous summer, in July 1942 the German Army no longer had enough armoured forces to bypass the city on either side and cut it off. It was going to have to make a frontal attack.

At the same time, Russian resistance in the Caucasus slowed the advance of Army Group A. Hitler sent General Jodl to investigate Field Marshal List’s lack of progress, only to have his own instructions quoted back at him. The stifling heat of the Ukranian summer did not make for cool tempers. In an incandescent rage, Hitler sacked List and announced that he would command the Army Group personally. List, 62, who had commanded the German 12th Army in France and the Balkans, was pensioned off and did not serve again. (List was one of several German officers sentenced to long jail terms at Nuremberg who found that their early release on health grounds gave them a new lease of life; he died in 1971.) Hitler was so furious with the rest of his generals that he refused to take his meals with them at Vinnitsa. As for the hapless Jodl, he was to be replaced by that rising star in the Nazi firmament – the hitherto undefeated commander of the 6th Army, General Friedrich Paulus, whose men were fighting their way into Stalingrad.8