NEW YORK STATE CAPITOL BUILDING IN ALBANY

Chapter 2

First Chances to Serve

Settling down to married life in New York City, Roosevelt began his law studies. He also found a new love: politics. Entering politics, though, was not easy.

Like his father and most wealthy men of the era, Roosevelt was a Republican. He joined the local Republican association, which helped elect party members to government offices. Roosevelt’s friends were surprised by this decision. They believed that politics was a career for common men, because politics was a dirty business. Political leaders, sometimes called bosses, could be rough and unpleasant. Roosevelt, however, wanted to be a political leader. He thought wealthy, well-educated men had a duty to enter government and try to make it better for everyone. He was determined to succeed in what he called the “rough and tumble” of New York City politics.

The leaders of the local association liked Roosevelt and helped him win his first political race. In the fall of 1881, he was elected to the New York State Assembly. At twenty-three, Roosevelt was the youngest lawmaker in the house. Alice supported his political career, and Theodore thought having such a charming and pretty wife would help him win political friends.

NEW YORK STATE CAPITOL BUILDING IN ALBANY

When he arrived in Albany, the capital of New York State, Roosevelt felt like the new kid in school. He didn’t know anyone else and he wasn’t sure what to do. But he quickly learned. Other lawmakers got used to hearing his high-pitched voice fill the state Capitol building. He spoke with a distinct accent, turning the word speaker into “spee-kar.” Roosevelt later became famous for often saying he was “dee-lighted” about something. And when he was particularly excited, he described the things he liked as being “bully,” meaning “excellent!”

Roosevelt became known as a reformer—someone who wanted to change government and society to help as many people as possible. He supported a law that would improve working conditions for people who made cigars. And Roosevelt believed he had to fight “crookedness” whether it was “great or small.”

While serving in the State Assembly, Roosevelt lived only part-time in Albany. On the weekends he headed back to New York City to be with Alice in the new home they had just purchased.

In 1883, the couple learned they were going to have a baby. Roosevelt decided to rent out his new home and have Alice move in with his mother. There, Mittie and Anna could take of her. He began making plans to build a new house in Oyster Bay, near his family’s summer home.

ANNA MITTIE ALICE

That fall he ran for the Assembly again and won. In January 1884, Roosevelt returned to the capital. In New York City, Alice was close to having her baby. On February 13, while in Albany, Roosevelt learned he was the father of a baby girl. But the joy of that news soon soured. Alice was not doing well, and his mother, Mittie, had also become very sick. Roosevelt caught a train home. He found the two most important women in his life were dying. Both his wife and his mother passed away early on the morning of February 14—Valentine’s Day.

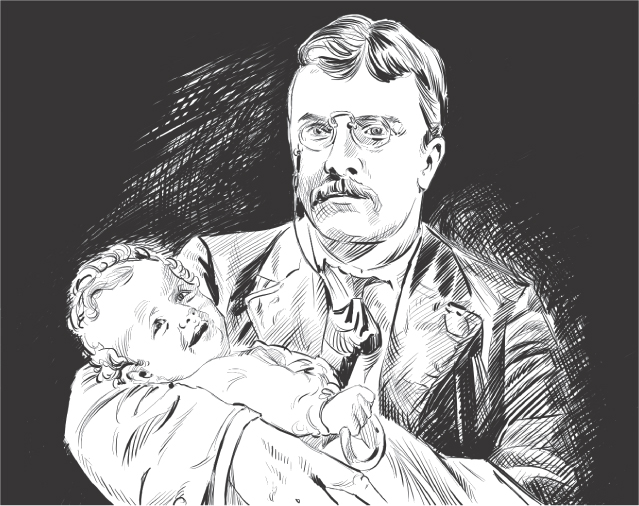

The double loss stunned Roosevelt. In his diary that day, he wrote, “The light has gone out of my life.” His newborn daughter was named Alice Lee, like her mother. Roosevelt never talked to young Alice about her mother, and he called his daughter by the nickname Baby Lee.

Theodore Roosevelt almost never spoke or wrote about Alice after her death. When he wrote the story of his life in 1913, he didn’t mention her once. He had spent years trying to forget his lost love.