Chapter 12

The First Conquest

Delfin Jaranilla had been nearly sixty years old at Bataan. He was thin and unimposing, with a long white goatee. A colonel and the judge advocate general of the Philippine Army, he was inducted into the U.S. Army weeks after Pearl Harbor.[1] His Philippine Army unit was evacuated to the Bataan Peninsula for what he would bitterly remember as “my baptism by fire.”

Although a crack shot with a rifle, Jaranilla’s battlefront task was holding courts-martial for Filipino deserters, sentencing those convicted to go back to the front. When the defeated Filipinos and Americans finally surrendered in April 1942, he hoped for decent treatment as a senior officer.[2] Yet as he later remembered, “a bearded Jap” snatched away his shoes and other possessions, smashing him with a rifle. Before Jaranilla could regain his senses, the Japanese officer dragged him to join the Bataan march northward.

Barefoot, relying on a bamboo cane, the old man staggered along. “Those who fell on their knees were beaten and bayoneted by the merciless Japanese,” he recalled. By the second day, hundreds of Filipinos had died from disease or beatings. Prisoners who could not walk “were murdered in cold-blood.” Some who tried to escape were caught and beheaded. When Jaranilla tried to help a Filipino officer who had collapsed from exhaustion, he counted himself “lucky the Japs only kicked me.”

“I was limping and could scarcely bear the pain,” he remembered. He considered escaping but could barely walk. Hungry and enervated, he blacked out on the road. He survived because a Japanese officer let a Filipina nurse take him to a nearby hospital.

For months afterward, he was detained at a former Philippine Army camp, later transferred to Bilibid Prison in Manila, where hundreds of prisoners of war were crammed into a cell meant for twenty men. After eventually being released during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, Jaranilla was so anti-Japanese that in 1943, when the collaborationist president of the Philippines was shot and nearly killed, he was questioned by the Kempeitai, who suspected the expert marksman.[3] In the final battle for Manila, his house was destroyed. The memory of Bataan would linger for the rest of his days, although with one consolation: he married the nurse who saved him.[4]

This was the man sent by the Philippines as its judge at the Tokyo trial. Jaranilla was the last of eleven to be chosen, alongside Radhabinod Pal of India. His appointment came in the waning days of American colonial rule, just a month before the Philippines became an independent country. He was hastily selected by Manuel Roxas, the aristocratic president of the Philippines.[5] Roxas himself was lucky not be in front of an Allied tribunal, rather than sending a judge to one; during the Japanese occupation, he had been part of the collaborationist government, prompting some members of the Roosevelt administration to call for him to hang. But he was sanitized by General Douglas MacArthur, who declared him a “great patriot” who had secretly spied for the resistance.[6] Unlike Roxas, Jaranilla had refused senior jobs in the pro-Japanese government, claiming that after Bataan he was too sick to work.[7]

Jaranilla’s devotion to the United States ran deep. As a young boy in the city of Iloilo, he had learned English by chatting with American soldiers near his Catholic seminary, doing so well that the Philippine government sent him to high school in California. Then it was on to the University of Tennessee and law school at Georgetown in 1907.[8] Anti-Asian discrimination was ubiquitous in the United States; he once played a violin solo as a musical interlude during a Georgetown student debate about Japanese immigration where it was argued that the Japanese as a race were superior to the Chinese.[9] Returning to the Philippines, Jaranilla had worked his way up from court clerk to attorney general in 1925, serving under six American governors general.[10] In the final days of World War II, Jaranilla was appointed to the Supreme Court of the Philippines, before being sent to Tokyo.[11]

He shared wholeheartedly in the American view of the war.[12] He was an ardent admirer of MacArthur, reinforcing his view of himself as a Christian savior of the Philippines. Jaranilla wrote to MacArthur during the Tokyo trial, “With your long years of duty in the Philippines and with your brilliant victory over the enemy, you certainly have helped immeasurably the Filipino people in successfully attaining their coveted freedom.”[13] When his wife had medical troubles, he was effusively grateful to MacArthur for helping to get her into a U.S. Army military hospital in Manila.[14] Proud of the Tokyo court, he argued that it would add more to international law than Nuremberg because of the wider range of legal traditions among the judges.[15]

Having personally endured Japanese war crimes, Jaranilla became a voice for the Asians who had suffered under Japanese conquest—particularly imperative since there was no Korean judge at Tokyo. He was consistently tough on the accused.[16] When confronted with procedural questions, his instinct was to speed the trial along.[17] He seethed at judges such as Bert Röling who took a more evenhanded approach.[18]

Mei Ruao liked him, finding him gregarious despite his ordeal at Bataan, often hosting boozy dinner parties.[19] Yet neither Jaranilla’s friendliness nor his suffering earned him respect among the European judges. “The Filipino judge was totally Americanized,” Röling said later. “He belonged to the ruling class in the Philippines which collaborated with the Americans. There was nothing Asian in his attitude at all.”[20] The British judge, Lord Patrick, saw him as a vengeful idiot who had no business on the court. “The Phillipine [sic] judge, appointed at America’s insistence, since we insisted that India must be represented, just doesn’t understand,” he wrote. “It is not lack of English, it is lack of gray matter with him.” He jeered, “Only one thing is certain, that he will vote on some ground for conviction. ‘Remember Bataan[.]’ He was in the ‘Death march of Bataan.’ ”[21]

As soon as the defense lawyers found out that Jaranilla had survived the Bataan death march, they filed a motion to remove him because of his “personal bias.” (Somehow the defense counsel did not realize that Mei might also be biased from the bombing of Chongqing.) How could he possibly be an impartial judge of Japanese war crimes when he had experienced them firsthand?[22] Ducking a legitimate issue, the judges again declared that they had no authority to undo an appointment made by the supreme commander. On June 13, Jaranilla took his seat alongside the other Allied judges.[23]

Soon after, MacArthur invited Jaranilla to be his guest on the grandstand in Manila for a ceremony celebrating the independence of the Philippines on July 4. As Jaranilla wrote ebulliently to MacArthur, that resonant date would no longer only mark “the birth of the greatest American Republic in the world” but also the day that “the flag of the independent Republic of the Philippines was hoisted as a symbol of a true independent nation.”[24]

Manchuria

Early in the prosecution’s case, two gigantic screens were put up behind the Japanese defendants, displaying maps of Asia. In overlays added for every year since 1931, Japanese-controlled territory was marked in livid red. What started in 1931 with the invasion of Manchuria would by 1941 distend to include vast reaches of Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. Tojo Hideki and the other defendants grimly strained their necks to look behind them at their unfolding conquests.[25]

China, above all, was drowned in red. The prosecutors argued that the Axis drive for world domination had started in earnest with the Japanese seizure of Manchuria, China’s three huge modern northeastern provinces.[26] Manchuria made a grand prize: an industrializing land as big as Britain and France put together, with massive economic potential, bordering Russia, temptingly close to Japanese-colonized Korea. The prosecution accused Japan of browbeating an unstable, fractious China into proffering special rights in Manchuria, ruling directly over the territories held by Japan’s powerful colonial railroad company, the South Manchuria Railway. Next, Japanese extremists plotted a provocation in order to conquer the territory outright, hoping to use the prodigious resources of Manchuria and northern China to fortify the army and build up Japanese heavy industry in order to ward off the predatory United States.[27] The flashpoint was an explosion along a stretch of track of the South Manchuria Railway near the city of Mukden (Shenyang) on September 18, 1931, which the prosecution said had been staged by officers of Japan’s renegade Kwantung Army. This so-called Mukden incident became a pretext for Japanese troops to attack a nearby Chinese base, which was quickly followed by an invasion by more than forty thousand Japanese soldiers. Japan nimbly conquered Manchuria while losing as few as three thousand troops, as well as five thousand wounded and over two thousand with frostbite.[28] Despite the Tokyo trial’s narrative blaming only a small military clique, Japanese society had been widely swept with war fever. Instead of annexation, Japan in 1932 set up a puppet regime, styled as the independent state of Manchukuo (Manzhouguo), which inspired utopian dreams among Japanese imperialists. To lend Manchukuo legitimacy, Japan had installed as its nominal ruler Puyi, the last emperor of China’s Qing dynasty, toppled as a young boy in the revolution that created the Republic of China.[29]

The next “incident” came in July 1937: a skirmish at the Marco Polo Bridge, outside of Beijing, which Japan took as a cue to march troops into the Chinese mainland, seizing Shanghai and the Nationalist capital of Nanjing, soon occupying much of coastal China. Echoing the nineteenth-century Opium Wars with the British Empire, prosecutors accused Japan of using opium as a military weapon to undermine Chinese morale. From July 1937 to June 1941, according to an Imperial Japanese yearbook, over two million Chinese had been killed and almost four million Chinese troops had died, been wounded, or taken prisoner.[30]

A long queue of Japanese waiting to watch their former leaders on trial, 1946

Xiang Zhejun, the Chinese associate prosecutor, rose to his feet to debunk the Japanese official claim that these conflicts were merely a “Manchurian incident” and a “China incident,” murky confrontations with blame on both sides, not rising to the level of war. Japan had taken “warlike actions” in Manchuria, he said, killing thousands of Chinese soldiers and civilians. Japan had “started a war at Marco Polo Bridge…. Later, Japan sent her soldiers all over China killing millions and millions of soldiers as well as children, women, and helpless civilians…. If that were not war, what is a war?” Bolstering Keenan, he added that the Tokyo trial was “not making new laws,” but “simply embodies law and the principles already in existence.”[31]

Starting its case in 1928 with the militarization of Japanese society, the Tokyo trial did not consider previous imperial conquests of Korea or Taiwan in the Meiji era. “We do not have the right to evaluate the merit of the annexation of Korea,” wrote the French judge, Henri Bernard, noting that the judges repeatedly refused to rewind that far.[32] It was in Manchuria, on the prosecution’s account, that Japan committed itself to a ruinous drive for expansion, pursuing mirages of self-sufficiency and economic autarky through a widening series of conquests—next Southeast Asia, and finally in a desperate war against the French, British, and Dutch Empires and the United States.[33]

“They Wag Their Tails and Beg Our Sympathy”

As the Manchuria phase began in the Ichigaya courtroom, the Republic of China joined in the Allied reconstruction of a peaceful Japan. For China, this project had a terrifying urgency. As a Chinese diplomat in Tokyo warned, if “Japan returns to the old anti-democratic, anti-peace orbit, then it is our country that will bear the brunt.”[34]

China urged the United States, the Soviet Union, and Britain to disarm Japan completely. Wang Shijie, China’s foreign minister, told General George Marshall that only “the complete demilitarization of Japan” could eliminate the risk of renewed aggression.[35] Japan could not be allowed to rearm for at least three decades, until its people had embraced peace and democracy.[36] An influential Chinese general cautioned his government that Germany after World War I had been allowed to keep a small core of military forces, which it had expanded into an all-conquering army. Although not wanting to enslave or exploit the Japanese, “who are of the same race and culture as we are,” this general warned that “Japan swallows the humiliation of American occupation and flatters America only to preserve its national power for revenge in the next great war.”[37]

China’s goal was to transform Japan to make it democratic and unthreatening. In one report approved by Guo Taiqi, a top diplomat and former Chinese foreign minister, the Chinese authorities sought to uproot what they saw as cultural sources of Japanese aggression in State Shinto, stamping out police powers used to enslave the minds of the people, implementing sweeping land reform, and remaking a school curriculum that had promoted national superiority.[38] That Chinese general argued for encouraging the defeated Japanese “to realize their hope for personal freedom and respect for human rights,” because democracy would nurture peace.[39]

As the Manchuria phase was getting under way, a Chinese investigator working with the Allied prosecutors privately told his government, “The trial will expose the real face of Japan’s aggressive war and brutality, thereby educating the Japanese nation to purge aggressive thoughts.”[40] Yet Chinese officials fretted that the General Headquarters program had not eradicated the country’s militarism. The Foreign Ministry’s Asia political team wanted an extensive purge, while the Defense Ministry wanted to ban war movies and forbid Japanese from doing judo, kendo, or any Bushido-style sports.[41] Despite the purges, a Chinese official in Tokyo warned that “the aggressive spirit in Japanese politics and society is so prevalent and deep” that it would be hard to eradicate. Like many Chinese, this official wanted the Allied occupiers to get tougher: executing or dispossessing the most important militarists, sentencing the rest to prison or forced labor.[42]

China sought Japanese compensation for its wartime devastation, including pensions for the dead or injured. The total was an astonishing butcher’s bill of 1,045,972,697,570,744 yuan, which comes out to roughly $87 billion—an enormous sum at the time, when, for comparison, the United States was helping to prop up postwar Britain with a loan of $3.75 billion.[43] The staggering scale of the losses was tallied with eerie bureaucratic specificity: more than 800,000 rifles, 63,000 machine guns, 5.7 million mortar shells, 3.6 million cannon shells, 1.3 million antiaircraft shells, almost 20 million grenades, 1.7 billion bullets, 267 hospitals, and more than 200,000 horses and mules. The Chinese air force had lost 1,813 fighters, interceptors, bombers, and other airplanes. The most painful losses could never be repaid: almost 3.4 million dead in the army and more than 14,000 in the air force.[44]

Chiang Kai-shek’s government was cautious about abolishing the monarchy, even though Chinese officials believed that the emperor was deeply implicated in Japan’s aggressions.[45] “Hirohito is responsible for war crimes committed during the Japanese war of aggression” in myriad ways, a Chinese diplomat argued. Under the Meiji constitution, he argued, the monarch was the head of the empire and wielded supreme command over the army and navy. The emperor’s authority had been used to put Japan on a war footing and forge the Tripartite Pact with Nazi Germany and fascist Italy; he had authorized the invasion of Manchuria and the occupation of China; he had presided over the imperial conferences which deliberated about attacking the United States and the British Empire; he had issued imperial rescripts sanctioning Japan’s withdrawal from the League of Nations, blessing the Tripartite Pact, honoring soldiers killed in battle, and declaring war on the United States and the British Empire.[46]

Many Chinese officials wanted to scrap the monarchy immediately, before rightists could use the throne to lead Japan into new wars.[47] The Foreign Ministry’s Asia political staffers wanted to permanently abolish the imperial system; if that was not possible, the emperor should be demoted to a king and stripped of any privileges that could stand in the way of democracy.[48]

Yet despite that, China’s government held back. When Australia put Hirohito on its list of war criminals, China’s Foreign Ministry wanted to have the same policy as the United States, not expressing any strong opinions before finding out what MacArthur wanted.[49] In the end, China deferentially left the emperor off its list of war criminals.[50] Later, the Chinese government preferred to leave the fate of the emperor to the collective decision of the Allied powers. If the monarchy remained, the constitution should be democratized “to return the Emperor’s power to the Japanese people.”[51]

For all the talk of democracy, though, many Chinese officials worried about what direction a democratic Japan might take.[52] Chinese diplomats favored Japan’s social democrats—at that time organized as the Japan Socialist Party—whose principles were similar to those of China’s Nationalists, hoping to build them up and perhaps quietly take control of them.[53] But the other political parties, as a Chinese official in the Tokyo embassy wrote, were either violent leftists or rightists who had escaped punishment.[54] Chiang’s government particularly dreaded the prospect that the Japanese Communists might win power, creating a government sympathetic to Mao Zedong.[55]

A Chinese war crimes investigator warned the Foreign Ministry that prosecutions had left the Japanese unrepentant: “I am deeply aware that they not only failed to wake up but deepened their contempt for our country.”[56] A Chinese intelligence officer cautioned harshly that while the Japanese appeared submissive now, they were such a stubborn nation that they could rise again like the Germans: “We have to destroy Japan’s national culture through collective control.”[57] Using a common Chinese slur for the Japanese, he wrote, “The Wo”—the dwarfs—“are inherently ruthless and exceptionally tricky. After their defeat, they are like caged beasts. To survive, they wag their tails and beg our sympathy. To kill them is not benevolent on our side. It’s better to assimilate and influence them with our morality so as to protect China from future scourges.”[58]

Three Prime Ministers and One Ghost

While Chinese officials fretted, the Allied prosecutors called the first of a long list of spectacular witnesses that would mark the Tokyo trial. Rather than foreigners hostile to Japan, though, the prosecutors relied heavily on the testimonials of centrist Japanese statesmen. The scene in Ichigaya often looked less like an international trial than a purely Japanese one, pitting liberal leaders against their hard-line successors. Civilian politicians who had been terrified to defy the swaggering generals and colonels were now able to slag them off without fear.

In the Manchuria phase, the high-profile witnesses included three Japanese prime ministers who unveiled the innermost disputes within their government—an unprecedented inside glimpse that helped to discredit the bellicose nationalists for much of the Japanese public.[59]

The first ex-premier was Baron Shidehara Kijuro, who until about a month ago had been prime minister supervising the country’s demilitarization, and was now a minister in the government. He was renowned for his peaceful policies as foreign minister in the 1920s, at the end of the internationalist and liberalizing Taisho period, and for opposing the invasion of Manchuria. Handsome in a well-tailored suit, with a neat mustache and round spectacles, he stood out as a man of rank. At seventy-three years old, he walked slowly, but his mind was sharp. A Japanese newspaper reporter admired his adroit responses as befitting a senior statesman.[60] None of this earned him deference from Sir William Webb, who, when the former premier was asked to speak in his rather good English, snapped, “His English is impossible. Get him back into Japanese.”[61]

Shidehara glowered stonily at the defendants.[62] As foreign minister in 1931, his conciliatory “Shidehara diplomacy” had envisioned a peaceful Asia built on interdependence between coexisting sovereign countries.[63] For that he had been reviled by several of the defendants now on trial, including General Doihara Kenji. Shidehara had tried in vain to get the headstrong Kwantung Army to withdraw from its Manchurian gains in 1931, as well as objecting bitterly to its scheme to enthrone Puyi, the last Qing emperor, as the royal figurehead of a Japanese-controlled regime in Manchuria. Shidehara had argued firmly that this was folly: the creation of an obviously artificial Manchukuo would only alienate the League of Nations; Puyi himself was an undemocratic anachronism; the Han Chinese in Manchuria would not embrace a Manchu emperor; and his installation would make it impossible to reach a peaceful resolution with China.[64]

Shidehara painted a terrifying picture of an army beyond civilian control. As often happened during the trial, he gave his main account through an affidavit, a time-saving measure adopted by the court, before facing cross-examination. Strikingly, he testified that the Japanese cabinet could not directly command the army. After all, under the constitution the army answered to the emperor, and the military could for all practical purposes sink a government by disapproving of its choice of army or navy ministers; at best, the cabinet could pass along its opinions about military policy through the army minister. He explained bluntly, “The Cabinet was not in a position to discipline either the army in Manchuria or any army anywhere.” Soon before the invasion of Manchuria, he had tried to block “the military clique” from invading; when the cabinet had been unable to control the army, it had resigned.[65] Under a stern cross-examination that reminded a Japanese reporter of machine gun fire, he dropped another bombshell: Japan’s troops in its colonial possession of Korea had, without the knowledge of the cabinet or the authority of the emperor, reinforced the Japanese forces in Manchuria.[66]

The next prime minister to testify was Baron Wakatsuki Reijiro, the centrist prime minister under whom Shidehara had served as foreign minister early in the Manchuria crisis, now a gaunt, white-haired octogenarian with a fading memory.[67] His statement and testimony reinforced the picture of an ungovernable military. His army minister, General Minami Jiro—now one of the defendants—had ignored the reluctant cabinet as Japanese troops plowed into Chinese territory. Day after day, Minami had reassured the helpless Wakatsuki that the troops would go no farther, and day after day they had advanced anyway.

Still, the elderly Wakatsuki wilted under cross-examination, often unable to remember details, with Minami’s defense lawyer pressing him into conceding that his cabinet had accepted the Kwantung Army’s claims that it was acting in self-defense against Chinese provocations.[68] Ridiculing the indictment, an American defense lawyer asked the former prime minister, “Do you know of any plan or conspiracy…to plan and wage wars of aggression, to conquer China and the Pacific Ocean, and eventually the world?” Wakatsuki had to reply, “I have never heard of anything of the kind.”[69]

Tellingly, one former prime minister was not there to testify, his absence the starkest testament to the constant terror of coups and assassinations which had blighted the 1930s. Inukai Tsuyoshi, who had succeeded Wakatsuki as prime minister, had been gunned down by young military officers during the notorious coup attempt of May 1932. An advocate of cabinet government, he did not lack for bravery; he had refused to flee the prime minister’s office, and after being shot repeatedly, he had said that he wanted to keep talking to the young officers.[70] Now, in the Army Ministry courtroom, Inukai’s son, who had been his father’s private secretary and had urged him to flee the assassins on that terrible day, emotionally claimed that his father had tried to pull back Japanese troops from Manchuria, which helped to mark him as an enemy to the ultranationalists.[71]

Inukai’s son testified that his father had met with Hirohito himself seeking an imperial rescript ordering the army out of Manchuria but had been rebuffed. At this, Marquis Kido Koichi’s lawyer leapt into action in defense of the emperor. Asked if he meant that the emperor was responsible for the army’s failure to pull out of Manchuria, Inukai’s son, who would later become justice minister, retreated, assuring the court that “His Majesty was a strong advocate of peace and had a very strong desire for an amicable settlement of the Manchurian Incident.”

Webb, who kept Hirohito in his crosshairs throughout the trial, fumed. The next day, for the first time directly quizzing a witness, he pressed Inukai’s son: if the emperor was such a lover of peace, why had he refused to issue that imperial rescript bringing the army to heel? Inukai’s son uncomfortably explained that “it is the feeling of the Japanese to avoid bringing the name of our Emperor into this argument.” Backtracking, he said that he was now unsure whether his father had directly asked for such an imperial rescript, or simply made his request known through Kido or other channels. Hirohito, he said, had given Inukai an audience and had expressed his hope for an end to the crisis and a lasting peace with China. Webb disdainfully cut the witness off, saying that the court had heard enough.[72]

Left unsaid was that Hirohito, despite his private misgivings that the Manchurian invasion was leaving Japan isolated, had in fact issued an imperial rescript in support of the Kwantung Army’s adventurism. The emperor, who was officially in control of the ungovernable Kwantung Army, had on January 4, 1932—the fiftieth anniversary of the Meiji Emperor’s famous Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors putting the military under the eternal command of the emperor—praised the Kwantung Army for fighting bravely in “self-defense” against Chinese “bandits.”[73] In Kido’s diary around the same time, the marquis had noted that the emperor’s wish to rein in the Manchurian invasion had enraged the army, so much so that Kido and other civilian leaders had decided that Hirohito should not say anything more about Manchuria policy unless he absolutely had to.[74]

The third prime minister was Okada Keisuke, who had barely avoided assassination himself. A navy minister and then a member of the Supreme War Council during much of the Manchuria crisis, he had become prime minister in 1934. In the Army Ministry courtroom, Okada gave a statement that he had received numerous reports that the army was planning to stage an incident to give them a pretext to grab Manchuria. As navy minister, he had been briefed that the explosion along the South Manchuria Railway “was plotted and arranged by the clique in the Kwantung Army.” He recalled the shock of the civilian government when Japanese troops in Korea had “crossed the border and participated in this occupation without any Imperial sanction.” The Kwantung Army, he said, had been the real power in Manchuria, outside the control of the government.[75]

Vividly showing the dangers of standing up to the military, Okada gave a sworn statement about the major putsch attempt in February 1936, when a score of officers and over a thousand troops “terrorized Tokyo for three and a half days.” They had seized his official residence as prime minister, the Diet, police headquarters, and the Army Ministry—the very spot where the trial was occurring. The radicals had killed his finance minister and several other senior officials with machine guns. He had barely escaped. His brother-in-law, mistaken for him, had been shot dead. After the slaughter, he and his cabinet had resigned under the shadow of the army’s dominance of the country.[76]

Not all the Japanese witnesses were so effective. Hoping to expose the inner workings of Japan’s government, the prosecution made the rash decision to make use of Major General Tanaka Ryukichi, a former aide to Tojo. A portly, round-faced, hard-eyed man who testified wearing civilian suits, he was out to settle scores with Tojo and other old rivals.[77] Hirohito had complained privately about Tanaka’s bad reputation, saying that Tojo’s own image had been tarnished by employing such a person.[78] When asked by a defense lawyer about his nickname “the monster,” Tanaka gave a sinister laugh that was apparently meant to be jolly. Not only did Tanaka prove unreliable, he would later testify for the defense as well. For the Chinese, he was especially abhorrent as the commander of Japan’s North China Area Army, which under him in 1940 had developed plans for crushing areas of Chinese guerrilla resistance.[79] Yet the general was allowed to spend several days on the stand loudly testifying about Japanese army plots, tarring Tojo as well as other army defendants.[80]

While personal testimony was important, the prosecution scored some of its most palpable hits with internal Japanese documents. Throughout the trial, the prosecution’s leading piece of evidence was Kido’s diary: a massive record of the inside deliberations of the Japanese government and court, fifteen volumes in full, running to over five thousand pages.[81] It implicated not just its author but also many of the defendants, although it showed more backstabbing and intrigue than a smoothly functioning conspiracy. In September 1931, Kido had recorded that the army was so determined in its Manchurian land grab that it might not obey orders from the government.[82]

The prosecutors introduced damning telegrams from several Japanese consuls to Shidehara, revealing the split between Japanese moderates and the hotspurs on trial. The Japanese consul in Mukden had warned that the Kwantung Army was about to go on the offensive along the South Manchuria Railway. Other cables revealed Japanese military officials planning to create Manchukuo and install Puyi, the overthrown Qing emperor, with a formal declaration of independence meant to hoodwink the League of Nations. Doihara, nicknamed “Lawrence of Manchuria,” was shown hard at work persuading Puyi to be Japan’s instrument, while simultaneously figuring out how to pretend that Japan had nothing to do with the restored emperor. If any Chinese troops dared to challenge the puppet state, Doihara assured a nervous Puyi, who was terrified of assassins, the Kwantung Army would fight them off.[83]

In the cables, the accused convicted themselves with their own words. In one dispatch from January 1936, Hirota Koki, as foreign minister, outlined plans to encourage collaborator rule in north China under Japanese troops and the Kwantung Army. In August 1936, as prime minister in a government dominated by the military, Hirota’s cabinet issued an important bellicose directive that “the fundamental national policy to be established by the Empire is to secure the position of the Empire on the East Asia Continent by dint of diplomatic policy and national defense…as well as to advance and develop the Empire toward the South Seas.”[84]

Reminding the courtroom of how Japan’s invasion had scotched the idealistic interwar hopes of the League of Nations, the prosecutors introduced a major League report that had been adopted by the world body’s Assembly in 1933. (In his recent Imperial Palace monologues, Hirohito claimed that he had wanted to accept the report in its entirety but had feared opposing the cabinet, which wanted to reject it.)[85] The League had guardedly concluded that it “could not regard as self-defence” the military advances made by Japanese troops after the Mukden explosion. Despite Puyi’s bombastic claims that he had been propelled to the throne by the will of the Manchurian masses, it had been perfectly apparent that Japan wielded the real political power in Manchukuo.[86] The League commission had stingingly concluded, “It is…indisputable that, without any declaration of war, a large part of Chinese territory has been forcibly seized and occupied by Japanese troops and that, in consequence of this operation, it has been separated from and declared independent of the rest of China.”[87] In the end, only Japan had voted against the report at the League, with Matsuoka Yosuke storming out the door.[88]

The Marshall Mission

Of all the untutored Americans who could have benefited from the grand history lesson unfolding in the Ichigaya courtroom, Harry Truman took pride of place. His ill-preparedness particularly showed on Asia in general and China in particular. “I know very little about Chinese politics,” the president privately wrote in early 1946. “The one thing I am interested in is to see a strong China with a Democratic form of Government friendly to us. It is our only salvation for a peaceful Pacific policy.”[89] He remained uninformed about most of Asia, breezily falling back on ideology, myth, or bigoted stereotype, as he later admitted: “I thought India was pretty jammed with poor people and cows wandering around the streets, witch doctors and people sitting on hot coals and bathing in the Ganges and so on, but I did not realize that anyone thought it was important.”[90]

He was, at least, painfully aware of his inadequacies: “This head of mine should have been bigger and better proportioned. There ought to have been more brain and a larger bump of ego or something to give me an idea that there can be a No. 1 man in the world.” He remained glumly ill at ease with the job. “Well I’m here in the White House, the great white sepulcher of ambitions and reputations,” he confided in an unmailed letter to his wife. “I feel like a last year’s bird’s nest which is on its second year.”[91]

Truman began by supporting China’s Nationalist government, although skeptical of Chiang Kai-shek and wary of getting pulled into China’s internal quarrels. He thought that “Chiang’s gov’t fought side by side with us against our common enemy, that we have reason to believe that the so-called Commies in China not only did not help us but on occasion helped the Japs.”[92] He publicly pledged to help the Chinese nation achieve “the democratic objectives established for it by Dr. Sun Yat-sen.”[93]

Yet Truman soon grew alarmed by the brewing Chinese Civil War—so much that in late 1945 he sent no less than General George Marshall, who had been serving as U.S. Army chief of staff, to mediate between the Nationalists and Communists.[94] While professing faith in “a strong, united and democratic China,” Truman pressed for a cease-fire between Nationalists and Communists and then a national conference to resolve the country’s internal strife. He continued to recognize only the authority of Chiang’s Nationalist government, but pledged not to send American troops to take sides in China’s domestic struggle.[95] “We are all glad to welcome you back to trouble and strife,” MacArthur cabled Marshall with wry congratulations on the impossible job.[96] As Marshall spent thirteen frustrating months in China, Truman despaired about his high-profile envoy’s prospects. “Looks like Marshall will fail in China,” he wrote to his wife.[97]

It is too easy to assume, with the clarity of hindsight, that Communist victory was inevitable. While the Nationalist government was hobbled by its long war against Japan, it would only fall through a series of blunders. It alienated crucial local chiefs, business leaders, and intellectuals. It relied on brute force rather than winning over skeptics in the cities and in the far-flung reaches of the vast country. Infuriated by Communist provocations in Manchuria, Chiang lashed back in 1946 with a military offensive that would prove to be more than his rickety state could stand.[98]

On the bench in Tokyo, Mei Ruao was mortified that American mediation was necessary. “It’s inexcusable that our own affairs need foreign intervention,” he wrote as he heard of Marshall’s mission. “At the same time, what’s even scarier is our economic crisis.”[99] In the trial’s early months, he glumly watched Marshall’s mediation between the Nationalists and Communists.[100] He found it embarrassing and frightening to see the chaos in China, one of the war’s victors. His country’s unwinding made a miserable contrast with Japan, where MacArthur’s friendly policies had “let Japan take many economic advantages and gradually get on the path toward rejuvenation.”[101]

In a sign of the weakness of the Chinese state, the Manchurian case was presented not by the Chinese associate prosecutor but by Australian, American, and other prosecutors. The Chinese team seemed overmatched or irrelevant. Mei was preoccupied by China’s declining status. “What a bad showing,” he wrote in his diary.[102]

“Murder in Their Minds”

After the high drama of the opening days, the court settled into an uneasy routine. “To the foreigners in Tokyo,” wrote a top Indian diplomat, K. P. S. Menon, “the trial had all the lure of a glittering social event. Men and women flocked to it, oblivious of the fact that great issues affecting human lives and international law were at stake. The Japanese accused behaved with the stoic dignity of tragic characters.”[103]

Tojo followed the testimony keenly, his earphones almost always on, leaning forward as if to study an adversary.[104] When a defense lawyer complained about the conquerors passing judgment on the vanquished, Tojo suddenly raised his head.[105] While some of the generals retained their swagger, most defendants were ill at ease. As an Asahi Shimbun reporter noted, Kido Koichi’s “violent turbulence of inward emotion” was revealed in his reddening ears.[106] Two former foreign ministers were distinctly uncomfortable: Shigemitsu Mamoru seemingly detached, staring at the floor, and Togo Shigenori taking notes with a pencil.[107]

As courtroom officials whispered that the proceedings could take nine months, Webb tried to find ways to speed it up: taking affidavits, reprimanding the lawyers for technicalities, snarling at defense counsel for asking questions which he found too long, upbraiding the translators. He did so with an all-encompassing rudeness that offended the accused, the prosecutors, the judges, and everyone else. When Japanese defense lawyers addressed the court politely, he brusquely urged them to eliminate “every unnecessary word.”[108] He repeatedly exhorted the lawyers to get out the facts rather than dwell on fine evidentiary points, as would be done in a normal criminal trial.[109] At one point he cut off the testimony of a Japanese former cabinet minister: “That is enough; we have heard enough. We have heard some loquacious witnesses in this court, but none so loquacious as you.”[110] Once when the defense counsel complained about the use of affidavits instead of courtroom testimony, he snapped, “No sermons here. The laws of evidence do not apply; you ought to know that by this time.”[111] At another time, he shrugged off the gulfs among national legal systems: “There is no use in discussing the difference between the American system, the British system, the Dutch system, or the Russian system; we have no time for that here, nor would it lead us anywhere.”[112]

Webb swiftly alienated his fellow judges. He was the only judge with a microphone; the others sat in silent annoyance or gossiped to their seatmates. “Our President was a dictator,” recalled Röling.[113] Most significantly, the judges from Britain, Canada, and New Zealand united in frustration at Webb, a British bloc which would come to drive the court’s majority. As the New Zealand judge, Erima Harvey Northcroft, wrote confidentially to his prime minister, Webb “has an unfortunate manner of expression, generally querulous, invariably argumentative and frequently injudicious.” When the other judges scribbled notes to him, “he is often either, and sometimes both, hostile and unreceptive of our suggestions or incapable of understanding their purport or purpose.”[114]

The animosity toward Webb became so intense that the polite Canadian judge, E. Stuart McDougall, tried to soothe him with a gentle chat. Webb was privately fuming at the British and Dutch judges.[115] The British judge tried to defuse Webb’s entirely accurate impression that “the British Commonwealth Judges on the Tribunal are critical of and disappointed with your conduct of the proceedings of the Tribunal.” Teeth clenched, the British judge assured Webb of his esteem and confidence.[116]

Ensconced at the Imperial Hotel with their room and board paid, the judges lived in luxury unimaginable to ordinary Japanese inhabitants of Tokyo’s firebombed infrastructure.[117] Yet most of them wanted to go home. Mei, initially charmed by his colleagues, admitted in his diary that “it was quite boring to see the same judges day and night.”[118] Others were ill at ease in the public spotlight, with the British judge appalled by the photographers: “these people, if a chance to get a sensational picture should arise, would trample their own mother underfoot in their rush.”[119]

Wearing black judicial robes under glaring camera lights without air-conditioning, the judges wilted in the sweltering Tokyo summer heat. The Canadian justice, acclimatized to Montréal temperatures, was especially miserable.[120] Even Mei, who had endured the furnace heat of Chongqing, felt dizzy.[121] Webb adjourned the trial for a week in July because of the lack of air-conditioning, and considered decamping the court to a cooler city if too many people keeled over.[122] He wrote to General Headquarters, “Unless the members of the Tribunal, the prosecutors, or the accused are likely to collapse in any numbers, we must carry on.”[123] At the stifling Imperial Hotel, Röling privately wrote that he was “living as a mild nudist in my hotel rooms, just sufficiently covered to prevent hurting the feelings of the Japanese angels who bring me iced tea or ‘hotte cowee’ (as they call it).”[124]

More profoundly, most of the judges were uneasy living in Japan. Röling was alternatively fascinated and disgusted by Japan. What he appreciated best was the women, privately pining after Japanese girls with “skins as peaches” and “eyes laughing in a mysterious manner.” Like any prosaic tourist, he swooned for the cherry blossoms and—unlike the more politically obsessive Mei—was beguiled by the old conceit that they represented Japan’s youthful warriors, “fiercely living for just a moment, giving all for being beautiful, sacrificing yourself in the flower of your life, leaving behind nothing more than an admired memory.” Other than that, Röling found the country weird and unsettling. “I cannot understand this people,” he wrote to a friend. Japan was a land “where the men are bowing and smiling with murder in their minds, well hidden.”[125]

Furthermore, the judges understood how awkwardly their enterprise fit with the rest of the occupation. They were mostly foreign civilians in a scene dominated by U.S. soldiers. Among the military officers lodging at the Imperial Hotel, Röling admitted to “feeling as a civilian in this generals-hotel, between all those stars, a bit as a cloudy night.”[126] Mei wrote in his diary that other countries were frustrated with American dominance and MacArthur’s generous policy toward Japan.[127] Several of the judges would have shared the sentiments expressed by grouchy troops in the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF), headquartered at the Kure naval dockyards in southern Japan, who paid their disrespects to MacArthur with their version of the Lord’s Prayer:

the bcof prayer

Our General which art in Tokyo,

Douglas be thy name,

Thy kingdom be off limits to BCOF troops,

Thy will be done in BCOF,

As it is done in Tokyo,

Give us this day our daily directive,

And forgive us for trespassing in the American Occupation Zone,

As we forgive postal for jettisoning our mail;

And lead us not into insanity,

But deliver us from Kure,

For thine is the kingdom and thou art almighty,

For the period of the occupation,

Sallaam.[128]

The Last Emperor

After the parade of Japanese prime ministers came an even more spectacular witness: Puyi, the last emperor of China’s Qing dynasty, most recently the puppet emperor of Manchukuo.[129] His presence in the courtroom dazzled onlookers, even those repelled by his deeds. Newspapers across the world gobbled up coverage of the man they called Henry Puyi. (He had plucked the English appellation from a posh list of British royal names.) Röling privately marveled about “the situation in which one, every day, in the corridor meets the Emperor of China and says: ‘Hello, how are you this morning.’ I thought in former days that only in fairy tales do you meet the Emperor of China. And, still, I am not quite sure if that opinion was wrong.”[130]

Puyi’s fate had been a mystery since Soviet troops marched through Manchuria in the final days of World War II. Now the Soviets admitted that they had been holding him all along. The Soviets secretly meant to turn him over to China, but both the Chinese and Soviets quietly agreed that first he should serve his purpose as a witness at the Tokyo trial.[131] While he testified, the Soviets kept him locked up at their embassy there.[132]

Puyi looked gaunt as he emerged from a Soviet airplane at Atsugi airfield near Tokyo, escorted by Soviet secret police. At forty, the Son of Heaven looked decidedly common in round spectacles, a beret, and an ill-fitting suit, with an anxious expression on his face.[133] His old British tutor had once remembered the boy-emperor’s dual nature: a bright child who might have made a progressive constitutional monarch, but also a keen admirer of Benito Mussolini, albeit aware that he was not cut from the same hard stuff.[134]

Puyi was sunk in the downtrodden gloom of a man who had lost his throne no fewer than three times: first as a five-year-old boy when the Qing dynasty was overthrown in the revolutionary fervor that inaugurated the Republic of China, then restored by one warlord and ousted by another, and now dragged off by the Soviets. As a connoisseur of defeat, the Soviet varietal did not agree with him. He still considered himself a superior being and inwardly lurched between feeling insulted and terrified.[135]

For those Japanese who had believed that Puyi had been a legitimate ruler in Manchukuo, his comeuppance in Tokyo was an awkward precedent: an emperor hauled before a war crimes tribunal. True, he was not on trial—although he would later be charged as a war criminal in Communist China—but this royal humiliation could not sit well with Japanese monarchists. His links to the Japanese throne went deep. Puyi had been thrilled when the Kwantung Army had sent him to Tokyo for a royal visit with Hirohito in 1935, meant to provide some respectability for the hireling. The emperor of Japan had greeted the emperor of Manchukuo at the train station, attended a banquet for him, and inspected a military parade alongside him. The two monarchs had worn similar medal-festooned dress military uniforms, boots, and caps. Puyi had visited a shrine to the Meiji Emperor and a military hospital treating Japanese soldiers wounded in Manchuria. On his return to his hinterlands palace in Changchun, Puyi had issued an imperial rescript declaring, “We and His Majesty the Emperor of Japan are of one spirit.” Puyi had made a second trip to Tokyo in 1940, while he was adopting the Shinto worship of the sun goddess Amaterasu—the divine ancestor of Hirohito—as the official state religion of Manchukuo. This celestial merger had required a strained meeting with Hirohito, who had awkwardly said that he accepted the will of his Qing vassal in this matter.[136]

His Kwantung Army handlers had thrilled Puyi with visions of returning to the Forbidden City in Beijing in glory after the triumph of Japan’s invincible forces. Daydreaming of his lost empire, his first thought was that he would need to find some imperial dragon robes. Stuck instead in remote Changchun, Puyi had ascended his ersatz throne on the cold, drizzly morning of March 1, 1934, with as much royal chintz—crimson carpets, silk curtains, a high-backed chair, minions performing the ninefold bow—as could be mustered. Not long after, he was favored with a visit from Prince Chichibu, Hirohito’s brother, bearing the emperor’s congratulations and a lavish chrysanthemum medal. Yet his actual powers had been limited to having his household staffers flogged or beaten, in at least one case to death. For everything else, Puyi had taken his marching orders directly from the Kwantung Army, through a Japanese military attaché who wrote out his speeches in shaky Chinese, censored his mail, and told him where to go, whom to receive, what to tell his subjects, when to smile, and when to nod.[137]

As the war turned against Japan, Puyi was terrified: if his own troops did not kill him, the Soviets would. At farewell ceremonies to honor kamikazes sent off to die for their doomed empire, he was haunted by their ashen faces and the tears flowing down their youthful cheeks. He fled his grotty palace for the mountains. When told about Japan’s surrender, he fell on his knees thanking heaven that the Americans would spare Hirohito—until being told that the same deal did not apply to him. Frantically trying to reach Japan, loaded up with as much jewelry as he could grab, he got as far as Mukden airport before being caught by Soviet troops wielding submachine guns. He was packed off to a chilly hotel in Khabarovsk repurposed as a detention center, where he spent his depressed days hoarding his remaining jewels and listlessly memorizing books about Leninism. It was, he thought, still better than being turned over to the Chinese.[138]

The galleries were packed as the emperor entered the Ichigaya courtroom on a steamy August day. Familiar with gawking crowds, Puyi was unfazed by the hubbub as he was marched to the witness box by Soviet guards. Thin and clad in a poorly fitting dark suit, his collar sometimes askew, he was nervous at first but grew confident. Pensively stroking his chin with his forefinger, leaning back in the witness box, he testified with regal authority.

The Allied prosecutors meant to use their royal witness to expose Japan’s plan to conquer northeast China, with the Qing potentate confessing that he had been every inch the puppet that the newspapers said he was. By laying bare Japan’s mastery over Manchukuo, the Allied prosecutors hoped to expose the other purportedly autonomous states that later became part of the Japanese colonial playbook in such places as East Hebei and Inner Mongolia, as well as discrediting the pro-Japanese authority in China led by Wang Jingwei. The prosecutors meant to brand all of them—as well as collaborationist governments in the Philippines, Burma, and elsewhere—as tools of Japanese aggression.[139]

Puyi was privately unrepentant as he was dragged back and forth between the Soviet embassy and the Ichigaya courtroom.[140] “I did not think that I bore any responsibility, I did not wonder what kind of ideology it was that caused my crimes, and I had never heard of the necessity of thought reform,” he wrote years later, when he had restyled himself as a model citizen of Communist China, the final persona of his shape-shifting life.

His real peril now came from vengeful Soviets and Chinese, not a relatively docile panel of foreign judges. “I denounced Japanese war crimes with the greatest vehemence,” he later wrote. “But I never spoke of my own crimes, for fear that I would be condemned myself.” He later professed shame at his testimony, avoiding self-incrimination in order to protect himself from Chinese punishment.[141]

Joseph Keenan did the questioning of Puyi. Although the well-educated royal, his English rusty from disuse, had to speak through a clumsy Chinese translator, he still easily outmaneuvered the U.S. chief prosecutor. While the Japanese defendants glared daggers at him and the Chinese associate prosecutor repeatedly tried to shut him up, the Qing potentate nimbly presented himself as a helpless figurehead forced to serve the Japanese army or die.[142]

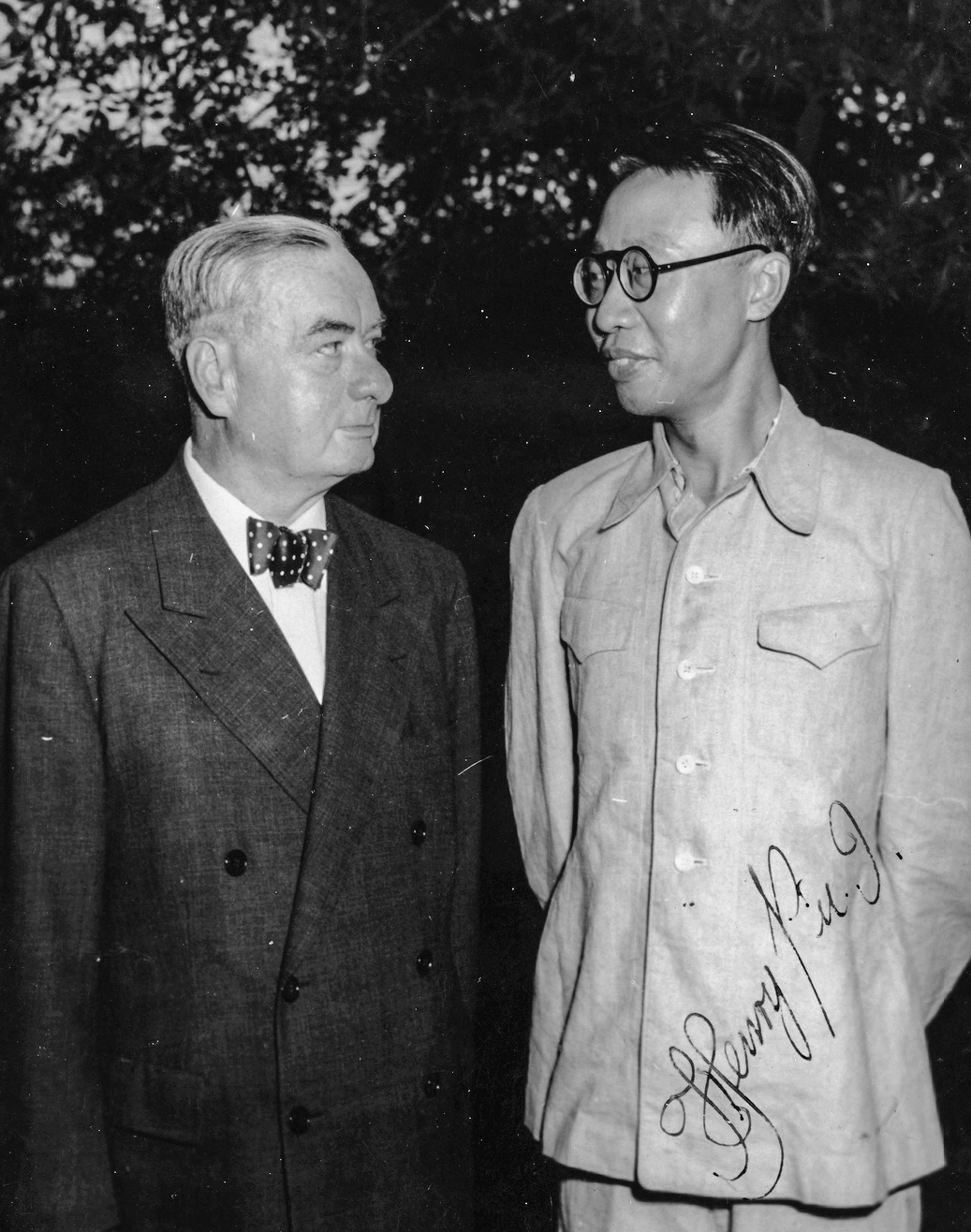

A wary Joseph Keenan, the U.S. chief prosecutor, and a smiling Puyi, the former Qing emperor of China, Tokyo, August 1946

Puyi testified that he had only agreed to head a Manchurian regime when told that the Kwantung Army might kill him if he did not comply, although he would later admit that he had been working with Japan long before.[143] “On paper, in order to cheat people the world over, they”—the Japanese—“make Manchukuo look as if it is an independent state,” he said. “But in actuality Manchukuo was being administered by the Kwantung Army.” Manchuria had really been a Japanese colony, with himself effectively a prisoner in his palace: “In actuality, the Emperor has no rights and power whatsoever.”[144]

As demonstrated by Puyi’s deference to his Soviet captors, he now served new masters. When Keenan asked if he had seen evidence of Soviet designs on Manchuria, the Soviet prisoner gave the only reply possible: “The Soviet Nation had no aggressive plan against Manchuria.”[145] This was too much for Röling, who was hostile to the Soviets throughout the trial. He correctly surmised that the Soviets had promised to turn the ex-emperor over to China for trial as a war criminal.[146]

In his most preposterous turn, the longtime Japanese instrument claimed to have been with the resistance all along. His young wife had comforted him by planning their revenge on the Japanese, he said, his voice raised with emotion, but they had poisoned her. (He would later write that he had no proof of that allegation and was playing up his grief to win sympathy.)[147] He testified that he had been biding his time in the hopes that the Chinese and Manchurians could one day strike back against the Japanese. “This was my ideal,” he said, “and so I entered into the mouth of the tiger.”

Webb interjected that fear of death did not excuse treason. “All this morning we have been listening to excuses by this man as to why he collaborated with the Japanese,” the Australian chief judge snapped. “I think we have heard enough.” Keenan, trying to protect his royal witness, irritably replied that he had not been aware than anyone other than the Japanese defendants were on trial. Webb barked back that Keenan would hear more if he wore his headphones.[148]

Puyi was not dissuaded. “In the Japanese plan they want to first enslave Manchuria and then China proper, and then East Asia, and then the whole world,” he asserted without evidence, to groans of protest from defense lawyers. Accusing Japan of a kind of religious aggression, he said, “Deep in my heart I opposed absolutely the invasion of the Japanese Shintoism”—a claim that called attention to how the promotion of State Shinto became a part of Japanese colonization in Taiwan, Korea, Singapore, Thailand, China, and elsewhere.[149] He made a spectacular but unreliable claim that Hirohito, making Shinto the official religion of Manchukuo, had given him a sacred sword and mirror, two of the three articles of the imperial regalia which had been bestowed by the sun goddess Amaterasu to her divine line. Puyi claimed to have wept: “that was the worst humiliation that I have ever faced.”[150]

One of the sharpest defense lawyers, Major Ben Bruce Blakeney, had previously written a withering profile of Puyi for Life magazine which slagged him as “only a puppet, a prisoner in his empire, a pathetic, self-effacing nonentity of an emperor, with an empire that is a fake.”[151] Given the unique opportunity to question his subject in the flesh, he conducted a relentless cross-examination meant to show that Puyi had eagerly seized the Japanese offer to restore him to gilded power. “Your first concern again, then, was to save your own life, was it?” he asked scornfully. The ex-emperor pounded the stand and waved his hands as he defended himself or evaded questions; offended by Blakeney’s impertinence, he retorted, “This is ridiculous.” He parried so well that the lawyers suspected that his English was better than he affected.

Blakeney pointed out that Puyi had long resented the Republic of China, which had swept him from his throne, and suggested that he had been eager to cooperate with Japan’s Kwantung Army to get it back. Puyi denied any such ambitions. The American defense lawyer bluntly explained that the Qing emperor was now a Soviet prisoner held under armed guard and was wanted for criminal prosecution in China. Since Puyi had already testified under oath that he had distorted the truth when menaced by the Japanese, Blakeney inquired, why would he not do the same for the Soviets and Chinese? Asked if the Soviets had said what they would do to him if he did not testify, again Puyi testily said, “This is ridiculous.” He was there, he lied, by his own free will.[152]

After Puyi completed ten days of testimony, Keenan wrote privately to him in custody at the Soviet embassy to thank him for enduring a “very severe ordeal” as a witness.[153] The Chinese associate prosecutor reported to his government with satisfaction that Puyi had provided “cogent statements” about Japan’s puppet government in Manchuria, as well as about its military, political, economic, and religious aggression there.[154]

Puyi was not the only famous Japanese collaborator who might have testified at the Tokyo trial. Subhas Chandra Bose and Wang Jingwei were both dead, but several leading figures of Japan’s pan-Asianist ambitions were under Allied lock and key. Ba Maw, an anti-British politician who had ruled a nominally independent Burma under Japanese domination, had been captured by the British and wound up in Sugamo Prison. Since his detention rankled with Burmese nationalists, the State Department, privately embarrassed, offloaded him back to Britain. The British did not want the headache of putting him on the witness stand in Tokyo, and instead pardoned him and flew him back to Burma.[155] The Philippine prosecutors had wanted to call José Laurel, the president of the Philippines under Japanese occupation, and Jorge Vargas, another prominent collaborationist. But after Puyi’s impressive courtroom showing, other Allied prosecutors feared that they might exonerate themselves if given their day in court.[156] So Puyi alone wound up as the face of pan-Asianist collaboration.

He was packed off onto a special Soviet flight to Vladivostok, where the Soviets were supposed to send him to Mukden to face the avenging authorities of the Republic of China.[157] In the end, though, he was brought back to captivity in the Soviet Union, where he was waited upon by members of his family; since they dared not call him “Your Majesty,” they instead discreetly called him “Above.” After China’s 1949 revolution brought Mao Zedong to power, the Soviets decided the time was right to turn Puyi over to a new Communist China.

In July 1950, he and other Manchurian collaborators were sent by train to China. Puyi was petrified. He dared not even hope for a painless death. His last years are chronicled in a memoir he wrote to please his final master in the Chinese Communist Party. He recounts being treated well, if gruffly, by the soldiers of the People’s Liberation Army, as he was transported to a reeducation prison camp for a thousand Japanese and Manchurian war criminals at Fushun, in northeastern China. He was alarmed by the drab prison with its high, dark brick walls, watchtowers, and barbed wire.[158]

As an official Chinese state account of Fushun prison brags, as the prisoners “acquired highly internationalization-oriented peaceful transformation in this humanitarian Chinese prison, they began to introspect in the depth of the minds on their own war crimes, examine the ugliness of their souls.”[159] Puyi’s memoir of his reeducation is less enthusiastic but ultimately follows the Chinese Communist Party script. He was won over by good medical care and tasty pork buns; he steeped himself in books with titles like Our New Democracy; he learned to make his own bed, brush his own teeth, tie his own shoes. He slowly realized that other people were laughing at him.

After two months in Fushun, he was moved to a wretched jail cell in a former Manchukuo prison in Harbin. He passed several nervous years there, indoctrinated that the benevolent Communist Party believed that even war criminals could remold themselves into new men. He wrote, “One fact stood out clearly in my mind: the Communist Party used reason to win people over.” Later he was sent back to Fushun to carry coal and study historical materialism. He was thrilled when, in 1959—in the depths of the terror-famine known as the Great Leap Forward—Mao himself allowed a special pardon for war criminals and enemies of the revolution. After ten years of reeducation, he stood with the Chinese people, their faces shining with joy in Maoist truth. At last, he wrote, his motherland had made him a man.[160]