Chapter 18

A Very British Coup

By now the British government feared that the Tokyo trial was collapsing. In a panic, the British secretly schemed to replace both the U.S. chief prosecutor and the Australian chief judge—a brazen assertion of state power over what was supposed to be an independent court.

The British associate prosecutor, Arthur Comyns Carr, warned direly that the prosecution was a shambles. He resentfully wrote to Sir Hartley Shawcross, Britain’s attorney general and its adroit prosecutor at Nuremberg, “It is amazing that the Americans, who started this as their show and merely invited us to help in a subordinate capacity, should be content to let it go to pieces now.”

Joseph Keenan, the American chief prosecutor, had suddenly bolted for Washington without telling anyone or leaving instructions, purportedly to consult with Harry Truman (“eyewash,” Comyns Carr thought). Several other U.S. prosecution lawyers had departed, leaving the prosecution relying heavily on its weary Commonwealth lawyers. Comyns Carr glumly reported that he would be left with only a few competent Canadian, Australian, and British staffers: “Of the non-Anglo-Saxons,” only a “young Dutchman” was of any use. Keenan, after staying off alcohol for months, had “been drinking heavily again for the last six weeks, with recent renewed semi-public exhibitions.” Comyns Carr volunteered himself as chief prosecutor instead, but refused to “act as an inebriate home attendant for Keenan.” The British associate prosecutor threw down the gauntlet: “I feel that the time has come when you will have to put your foot down with the Americans and say that unless they put the thing in order you will recall me.”[1]

Alarmed, Shawcross urged Ernest Bevin, Britain’s foreign secretary, to complain to the U.S. government about British “grave dissatisfaction” with Keenan in particular and the trial in general. Keenan “has become notorious not only for inefficiency but for almost constant insobriety.” Shawcross cautioned that “it would be most unfortunate if the trial broke down or if large numbers of the defendants were acquitted.”[2]

Britain’s Labour government resolved to oust Keenan and replace him with their own man. Bevin, a headstrong working-class unionist, was both an outspoken foe of the Soviet Union and a keen imperialist—a leader of the Labour Party’s postwar efforts to hold on to Britain’s colonies.[3] Asserting British power with all the swagger of a global empire, Bevin defied the United States, agreeing that the only solution was to put Comyns Carr in charge, either as chief prosecutor or as acting chief prosecutor while Keenan stayed away indefinitely.[4] Knowing who really ran the show, Bevin took the matter up with General Douglas MacArthur first, not bothering with the White House or State Department unless they got no satisfaction from him.[5]

MacArthur stopped the British cold. He was not about to replace the pliant Keenan for someone British. For an hour and a quarter, he chewed out the senior British diplomat sent on this disastrous errand. The supreme commander, as this wretched British official reported back to Bevin, was “highly incensed” and “violently hostile” to their mutinous proposal. Scorching Comyns Carr as an ambitious reprobate, MacArthur called it a “dastardly act to stab a man in the back and make accusations against him when he was not present to answer them.” He claimed that Keenan had not been drinking immoderately, and lauded him for the “monumental achievement” of getting prosecutors from eleven countries to function together. Quite falsely, MacArthur declared that he could not possibly be more pleased than he was with the functioning of the Tokyo trial. He denied that the prosecution was faltering, declaring its case to be “cast iron” and in many respects better than Nuremberg—a taunt sure to infuriate Shawcross.

“I entirely refuse to act as the British Government wishes me to in this case,” MacArthur growled. If there was to be a new chief prosecutor, he said, that would be an American; he had already given the British Commonwealth its due by making Sir William Webb the chief judge. Once the Allied governments had appointed their prosecutors, he said, he could not tamper with them. He pointed out that Harry Truman had taken a personal interest in Keenan’s appointment, and warned that there would be “unpleasant repercussions” if the British pushed this “unwelcome” matter. MacArthur put the British on notice: “I should like to warn you that if His Majesty’s Government take this to the United States Government they will find themselves up against President Truman himself.”

In a sop to the British, MacArthur pointed out that Keenan was in poor health, hospitalized in the United States, and was quite likely finished in Tokyo, unlikely to reappear. The British diplomat who had absorbed MacArthur’s wrath urged Bevin to slink away.[6]

After MacArthur bared his teeth, all British bravado vanished. Bevin and Shawcross tiptoed away; Comyns Carr did not resign.[7] A month later, the British got word that Keenan was coming back to Tokyo after all, which they accepted with bad grace. “It is obvious that Keenan is a political crony of Truman’s and that the latter would very much resent any suggestion that he should give his pal the sack,” wrote a British official sourly. The British resolved to stick it out to the end “to look after our interests.”[8]

Drafting

Bad as things were among the prosecutors, it was, if anything, worse between the judges. United only in resentment of Webb’s leadership, the judges were careening toward not just dissents but possibly several resignations. To groans, Webb told the other judges that in case they could not ultimately agree on one opinion, he was going to work on the court’s lead judgment, which was “my duty and privilege as President.”[9] He planned to write a comprehensive account of the development of international law about aggression, trimming his discussion of natural law but not abandoning it.[10]

The dispirited, feuding judges in Tokyo began writing drafts of parts of their judgment as early as February 1947, hoping to deliver a prompt verdict when the trial finally ended. It is common for judges in big, sprawling cases to start drafting their judgment while a trial is still under way. While this could reflect closed minds, it would be impractical to wait until the proceedings were over to start some sketching, and seasoned judges can roughly anticipate some of how a trial will unfold.[11] Unlike in a standard criminal trial, the judges arrived in Tokyo knowing plenty about the events of World War II. As Webb explained at one point, about a piece of defense evidence, “we cannot help knowing these things. We read them before we came to Japan.”[12]

To allow the judges to change their minds during the trial, Webb wanted to start with basic sections that would be required no matter what the verdicts were, such as an overview of the law and statements of the evidence in general. Because writing “a history involves conclusions,” Webb noted, he saw these draft studies as a prelude for the harder task of finding the individual accused guilty or innocent beyond reasonable doubt. Each of the judges would handle two of the twenty-five remaining defendants, except for Webb, who would handle seven, and Radhabinod Pal, who would take no part in any of this. Webb sometimes made the trial feel like a foregone conclusion: “It is hoped to have the statement against each accused prepared before the accused begin to give evidence.”[13]

Many of Webb’s assignments were roughly predictable: Mei Ruao would take China, Major General Ivan Zaryanov would handle Japan’s relations with the Axis, the influential New Zealander would handle the attacks on the United States and the British Empire, the French judge would cover French Indochina. For others, he was at first inclined to mix it up: the American judge would deal with Manchuria, the Filipino would cover Indonesia, and the Canadian would do the Soviet Union. Röling and Pal would be asked to deal with conventional war crimes, since those were the only offenses they were sure were actually criminal.[14]

The judges worked having heard out the Allied prosecution but not the other side. While the defense was still presenting its case on the invasion of China, Webb’s assistant had drawn up a summary of Japan’s militarization, its wars in Manchuria and the rest of China, and its Axis alliance.[15] Before the individual suspects got their chance to speak in their own defense, the U.S. judge drafted his preliminary findings of fact about Manchuria, and Webb circulated a study of the prosecution’s case on China.[16]

Röling, despite his disputes with the other judges, urged a united judgment. It was impossible for all the judges to fathom all the evidence, and he complained that the Nuremberg judgment had “no logical line” and seemed made up of disparate sections pasted together. Yet he was driven more by idealism:

This trial is of a special importance for the whole world, not only for the facts proven, or the kind of judgment delivered. It is more or less the touchstone for the possibility of organized international justice. We have, if possible, to prove by our activity that representatives of eleven nations can come together and really can cooperate. If it is true that the future of the world depends partly on the possibility of the creation of international courts, then it is of the utmost importance that we prove the possibility of international judicial cooperation. We would not prove that by producing unnecessarily more than one judgment.[17]

The Dutch judge was fascinated by his task, relishing the revelations from secret meetings, government telegrams, and speeches. Yet he found himself “looking more for understanding than for judgment.” Tasked with weighing the guilt of each accused, he instead saw “how individuals think to make history, and how they are in fact, by time and place chosen marionnets who fulfill a more or less necessary and predestined function.”[18] He worried that the work was corrupting his soul. He wrote to a friend: “Whoso handles pitch shall foul his fingers!”[19]

“A Squalid Farce in Japan”

The trio of British Commonwealth judges were disenchanted and despondent. By the spring of 1947, the unshowy judges from Canada and New Zealand had asked their governments to bring them home, while the British judge was seriously contemplating quitting.[20]

The British judge, who was from Scotland, vented his spleen in a blistering letter sent back home to a friend, Scotland’s top judge in Edinburgh. Although Lord Patrick kept an arm’s distance from the British government for the sake of appearances, he told his friend to circulate the letter as he saw fit, hinting with zero subtlety that “I only write it because I feel that people like the Lord Chancellor and the Attorney General should be prepared for the failure of the hopes which led to the appointment of this Tribunal. If you do not agree, put it in the fire.”

No way was this letter going into the fire. As intended, Patrick’s complaint was promptly sent on to the British lord chancellor and other senior officials in London, flaying Webb as “a quick-tempered turbulent bully…, resentful of the expression of any view differing from his own.” Patrick scoffed at France’s judge for suggesting that international law grew out of “le bon coeur,” and derided the Philippines’ judge as dependably vengeful but too stupid to understand how he was voting: “what his judgment will be like, or with what view he will concur no man can say.” The Soviet judge wanted “a lot of fulminations inserted about the dastardly attack by the fascist nations against the sacred rights of democracy.”

Patrick was especially appalled with the dissenters. He scorned Röling for arguing that aggression was not a crime while also voting that the court had jurisdiction: “In other words you keep poor devils on trial for their lives for eighteen months, although all the time you know you can never convict them.” Patrick reported with horror that Pal had circulated an opinion that was well over two hundred pages long, arguing that aggressive war was not a crime and that there was no individual criminal responsibility for acts of state. Suspecting that Pal meant to publish his dissent as a book, Patrick rebuked his own government for inflicting the Indian judge on the court: “He has made his position quite clear since first he was appointed, so why the Government of India ever nominated him, and why Great Britain insisted on India being represented on this Tribunal—America objecting—it is difficult to see.”[21] Patrick warned the senior British diplomat in Tokyo that Pal’s draft had some “thinly concealed backslaps at Great Britain.”[22]

Patrick anticipated catastrophe when the judges had to compose their final judgment. “Far from adding some weight to the Nurnberg judgment as a precedent in international law,” he wrote, the Tokyo judgment “will cast doubts on its soundness. It is a deplorable situation.” With considerable accuracy, he predicted what was to come:

We shall have a little core which will be on the same lines as Nurnberg. The President [Webb] will sustain the Indictment upon a special ground of contract, useless as a precedent for the future, the Frenchman will sustain it as being in accord with his “bon coeur.” Russia will sustain it because of Japan’s dastardly attack on democracy. The Phillipines [sic] will sustain it on I know not what grounds. And Holland and India will deliver a detailed attack on the grounds of the Nurnberg judgment.

The British judge lambasted his own government for not vetting the judges properly. “Britain should never go into such an International Court again without much more careful screening of the calibre of the members,” he wrote. “There are four members of this Tribunal whom no decent Lord Advocate would make Sheriff Substitute anywhere.” He was especially glum about Webb: “A man appointed because of the length of the entry he has had inserted in ‘Who’s Who’ can so antagonise the members of his court that the only purpose of the institution of the Tribunal is frustrated.”

He considered resigning, but feared that if he did so, at least two other judges—presumably the Canadian and New Zealander—would press their governments to let them quit too. “The trial would be quite discredited,” with a worrying impact on “world opinion and on the occupation of Japan.”[23]

The British government was appalled. “It would be very amusing were it not so tragic,” wrote a top British legal official. “It is indeed lamentable that these proceedings should undo much of the good of Nuremberg…. [T]he hopes with which we started this trial seem to have failed.” He wished that Patrick was running the tribunal instead of Webb.[24]

Soon after, Erima Harvey Northcroft, a Supreme Court judge in New Zealand, sent an equally dire warning to his chief justice, intending that he pass it along to the prime minister. “I am in despair,” Northcroft wrote. He excoriated Webb, who was “seldom wise or discreet in his utterances and much that he says and does can, and no doubt will[,] be used to create the impression that the trial has been an unjust one.”[25]

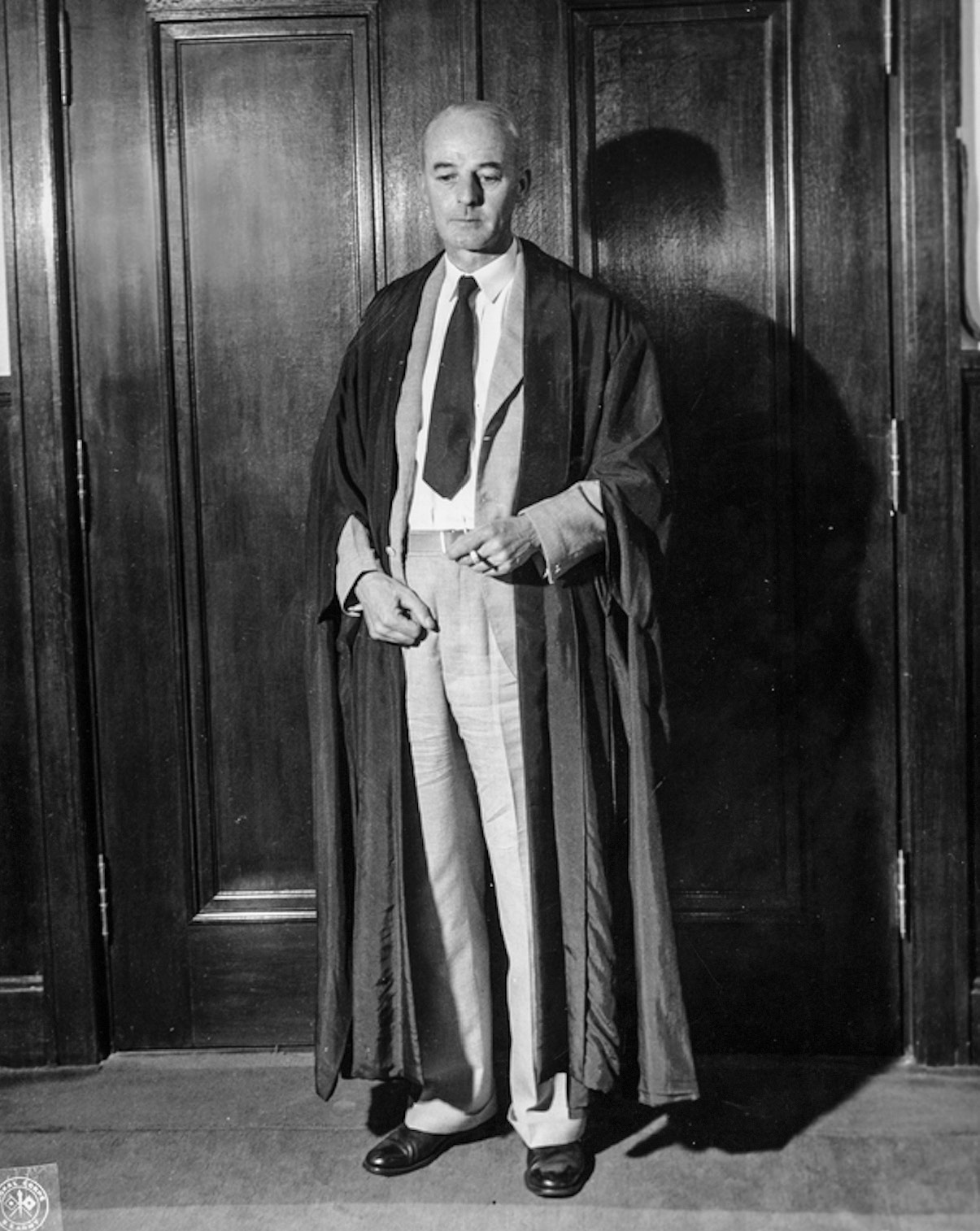

Lord Patrick, the British judge, in his chambers at the Tokyo trial, August 6, 1946

The Australian chief judge had split the judges between himself and everyone else. “Eleven so different Judges required a President of exceptional ability and disposition,” but Webb, “from the start, has preferred to ‘walk alone.’ He has behaved as a presiding Judge sitting with a jury, never as primus inter pares”—first among equals. Webb had been grossly offensive to him. While the other judges often ate together “as a judicial family” at the Imperial Hotel or at the Ichigaya courthouse, Webb had taken to snubbing the others, sometimes showily. Once he walked into the dining room at the former Army Ministry, saw the Canadian, New Zealand, and Soviet judges eating together, and rudely ignored them to sit down with a group of U.S. officials. It was impossible to talk business with him: “he regards any comment by anybody as criticism, to which he is acutely sensitive.”

Northcroft warned, “The Tribunal, if it is to make a useful contribution to international law, must be entirely or substantially of one mind. The chance to secure that, I fear, has gone.” Webb’s dismissal of his colleagues and his “determination to be the author of a monumental judgment has produced chaos.” He lamented that “everybody is working independently and I hate to think of the futility of persuading them to shed their pet theories and conclusions.” Pal had already written a draft dissent of no less than two hundred and fifty pages, while another judge—apparently Röling—was at work on another tree-killing dissent. “I fear the result of this long trial will be futile and valueless or worse,” Northcroft wrote morosely. “This Court will not speak with a clear voice upon any topic of law or fact. If a Court of this standing is seriously divided, and I feel sure it will be, then the modern advances in international law may suffer a serious setback…. Varying opinions from this Court including sharp dissent from Nuremberg must be disastrous.”

Finding his position “intolerable,” he begged his own government to let him resign and come home: “Discomfort and embarrassment I have accepted, and, of course, would continue to accept it if I thought I could advance the cause of international justice.” He urged finding some way to suspend the tribunal’s proceedings, in order to avoid a disastrous conclusion. Since he could not sway the court, “I feel entitled to ask for relief from the position in which I find myself.”[26]

Throwing discretion to the winds, Northcroft told a senior British official in Tokyo that he was so disgusted with the court that he had asked his government to withdraw him.[27] Informing a British general in Tokyo that Pal and Röling might well dissent, he warned that the result of the trial might negate the good done at Nuremberg. If possible without losing face, he wanted “to cancel it altogether.”[28]

The Empire Strikes Back

Patrick urged his government to act fast to save the Tokyo trial. He informed the top British diplomat in Tokyo that Webb’s “autocratic methods and rude and eccentric manner” had torn the judges apart, leaving a “fundamental disagreement between Webb and Dominions judges” about the final judgment.[29] In another letter to Whitehall by way of Edinburgh, Patrick indirectly urged the British government to force Webb out as chief judge of the court. The Canadian and New Zealand governments, he warned, were forced to consider pulling out of the Tokyo tribunal. Would Webb be ousted, or would the other three be? He asked bluntly: “Are we to be withdrawn?”

Patrick wrote that the Australian chief judge had “often been offensive to many of us,” recently rebuffing the stately Northcroft “in grossly offensive terms.” (Patrick unpersuasively feigned indifference to such “vulgar personal squabbles,” noting that Webb “is at times almost intolerable, but, as the Americans say, ‘I can take it.’ ”) If the British government let the judges muddle on, the final judgment and dissents would be mortifying.

What to do? If the British, Canadian, and New Zealand judges were allowed to stomp out of the Tokyo trial, that “would clear our countries of responsibility for the result of the Trial,” but would still leave the precedents set at Nuremberg in peril. Instead, Patrick clearly preferred that the British government “ask Australia to withdraw the President, who sets us all by the ears.” If Webb could be replaced by Northcroft as the chief judge, that antipodean shuffle would result in eight judges supporting the Nuremberg judgment. While Patrick obviously yearned to see Webb sent packing back to Queensland in disgrace, he politely told the British government that the question was above his pay grade: “The matter is one which concerns world politics and statesmanship.”[30]

Patrick’s note caused panic in the British government.[31] The shaken lord chancellor, a top British judicial official, vilified Webb for a “complete absence of any legal capacity” and mocked his natural law ruling (which the lord chancellor had not read) as “really a laughable document if it were not so serious.” He concluded that it would probably be necessary to ask Webb to retire. The lord chancellor, who had signed the London agreement that had created the Nuremberg tribunal, concluded, “It is a tragic thing that a trial which went so well at Nuremberg is degenerating into a squalid farce in Japan.”[32] He warned Shawcross, the attorney general, that “the tragic farce which is being played out in Japan” might “undo much of the good of Nuremberg.”[33]

The British quickly ruled out the New Zealand judge’s excitable suggestion of shutting down the trial.[34] Bevin notified the prime minister’s office that it would be “disastrous to abandon the trial now.” Doing so would “deal a shattering blow to European prestige,” and would “proclaim to the world that Japanese militarism had been justified since we had tried to convict it but failed.”[35]

Instead, the British secretly tried to whip the wayward Dutch judge into line. A senior British official alerted a Dutch counterpart that Röling was likely to dissent and challenge the Tokyo tribunal’s charter. The Dutch official checked with the commission of jurists who were supposed to control Röling, who themselves were somewhat dubious about the validity of the charter but claimed to have heard nothing about his dissent. “It is to be hoped that the Dutch judge will conform when the time comes,” the British official informed the Foreign Office.[36]

Shawcross gathered the lord chancellor, diplomats, and other mandarins at the House of Lords. After an anxious discussion, they decided to warn MacArthur about the impending dissents from the Indian and Dutch judges and the danger that the trial might break down altogether. They hoped, with MacArthur’s help, to send to Tokyo an eminent, elderly British jurist—who had chaired an important Allied war crimes commission preceding Nuremberg—to discreetly urge the judges not to impugn the court’s charter and to persuade Webb to change his tune. The lord chancellor suggested leaning on the Australian foreign minister to whip Webb into line.[37]

Patrick warned his government that this was a terrible plan. If that British jurist was sent to Tokyo, the other judges would deeply resent the attempt to interfere with their judgment and “Webb would blow off the handle.” Such a frontal assault would destroy any chance of making the other judges see the light; better that Patrick do his best to persuade his fellow judges to uphold the Nuremberg principles, while privately keeping in close touch with the British government. And if MacArthur were to pressure Webb, that would only further harden his views. Anyway, after convening the tribunal, MacArthur had no further authority over it and could not tamper with it.[38] After the court reached its verdict, MacArthur would have to review it; it would be improper, Patrick warned—rediscovering his concern for judicial independence—for the supreme commander to be informed of any disputes among the judges, or for him to do anything to influence its deliberations.[39]

The senior British diplomat in Tokyo was gingerly instructed to “avoid giving the impression that we are accusing an Australian judge to the Americans,” although that was precisely what the British were doing. He was ordered to warn MacArthur that the Tokyo judgment might thwart the Nuremberg judgment criminalizing aggressive war, and to explain that it was “absurd” that any of the judges should contemplate ruling that aggressive war was not a crime in international law.[40]

For the second time, MacArthur quickly put an end to a British plot. When the British diplomat approached MacArthur, he found that Webb’s careful cultivation of the supreme commander had paid off. To be sure, MacArthur was depressed by the prolix courtroom proceedings, aware of the prospect that the Tokyo court might defeat its own objectives, and indignant at the “American shysters” serving as defense lawyers, whom he thought were taking full advantage of the peculiar international character of the tribunal and dragging the trial out. Yet rather than repudiating Webb, MacArthur said that it was a pity that the Australian chief judge had not been given supreme power over the other judges and lamented that he was sometimes outvoted by them.

MacArthur, keen on punishment for Pearl Harbor, took little interest in the advancement of international law. He expected that most of the accused would be convicted but not necessarily according to the Nuremberg judgment. Yet he emphatically declared that the defendants responsible for attacking Pearl Harbor must surely be guilty, since they had started the war without prior declarations while negotiations between American and Japanese diplomats were still going on.[41]

With that salvo from MacArthur, the British government scurried away from its machinations against Webb, Pal, and Röling. As a British diplomat informed the lord chancellor, “in view of the delicacy of General MacArthur’s position vis-a-vis the Tribunal,” there was “no useful purpose” in pestering him.[42] The lord chancellor glumly agreed. All that the British government could do was hope that Patrick would prevail over the other judges.[43]

Bevin, who had ably served as labor minister in Winston Churchill’s wartime coalition government, worried that Nuremberg’s legacy was at stake. Patrick would have to remain to win over those judges who were “considering questioning in their judgments that Nuremberg doctrine that waging an aggressive war is a crime. This is a serious matter, not only because of its effects on the Tokyo trial itself, but because it would weaken the force of the Nuremberg judgment.” If Patrick was withdrawn, there might be “only a bare majority, if that, for the Nuremberg doctrine.”[44]

Under pressure, the British and Canadian judges backed away from their threats to quit. The Canadian judge decided that doing so would be unpatriotic. Patrick, who had been hospitalized and keenly wished to get out of Japan for his own health, realized that this would be impossible.[45] When Scotland’s top judge tried to bring him home to help the overburdened Scottish courts, Bevin snapped that this would be disastrous. It would then be impossible to hold back the Canadian and New Zealand judges as well, which could turn the trial into “a farce.” There was, Bevin declared, no question of withdrawing the British judge from Tokyo before the bitter end.[46] He instructed the Canadians that “they must stick it out.”[47] Patrick pledged himself to trying to lead Webb, Röling, and Pal back into line with the Nuremberg judgment.[48]

The Plague

Grim as the litany of war crimes before the judges was, the United States was secretly covering up what it knew about some of Japan’s most shocking atrocities.

Hidden away outside the frigid northeastern city of Harbin in occupied Manchuria, the Japanese army had since 1936 operated a top secret unit for human experiments with bacteriological warfare. In its hellish work, Unit 731 had killed some two thousand Chinese and Manchurian prisoners, as well as launching attacks on several Chinese cities. The operation had been run by General Ishii Shiro, a microbiologist who had been captured by the Americans and remained in their custody. According to U.S. intelligence, Unit 731 had produced some four hundred kilograms of dried anthrax—which, if aerosolized properly and carefully spewed by airplane over a big city, could have killed hundreds of thousands, and perhaps even millions, of people.[49]

Japan had used its secret biological weapon against Chinese targets. In 1940 and 1941, with approval from Japan’s army, Ishii’s team flew a small airplane low over the Chinese cities of Quzhou, Ningbo, Jinhua, and Changde, spraying plague-ridden fleas and grains. Soon plague broke out in all the cities except Jinhua. In 1942, Ishii’s teams used germ bombs and spray to support the conventional warfare of the Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign. Some 250,000 Chinese civilians died in that onslaught, although it is not clear how many of them perished from the weapons of plague, cholera, and anthrax. Japan also set up a secret facility in occupied Singapore to do biowarfare experiments on humans, as well as centers in China and Burma.[50]

Both General Headquarters and the office of the U.S. Army chief of staff—by this time, General Dwight Eisenhower—knew a great deal about Unit 731’s work.[51] Yet the Tokyo trial’s prosecutors quietly avoided the issue. Ishii would not face trial at Tokyo nor the U.S. military courts at Yokohama. Nor would the Allied prosecutors pursue germ warfare charges against three generals already on trial in Tokyo who had supported Ishii’s work: Umezu Yoshijiro, Araki Sadao, and Tojo Hideki himself, who had spent three years in Manchukuo and was familiar with the secret program.[52] To the contrary, the United States and the Soviet Union sought to learn more about the human experiments for their own military purposes.[53]

As the defense was getting under way in February 1947, the Soviet prosecutor at the Tokyo trial, Sergei Golunsky, asked the Americans for permission to interrogate Ishii and two Japanese colonels running the experiments. General Headquarters would not allow Ishii to be prosecuted, while some of its officials hoped that the Soviets would not get much out of him that the Americans had not already gleaned from their own interrogations. U.S. officials were skeptical that the Soviets would be interested in prosecuting Ishii’s unit for crimes committed against Chinese, and as MacArthur’s staffers noted with alarm, they had expressed an interest in the mass production of typhus and cholera bacteria, as well as typhus-bearing fleas.[54]

Wary of letting the Soviets learn about how to churn out typhus and cholera, the State and War Departments agreed only to a onetime interrogation strictly controlled by General Headquarters, grudgingly allowed as “an amiable gesture toward a friendly Government.” The Japanese colonels, the U.S. government ordered, would first be questioned by U.S. interrogators. If they said anything noteworthy, they would be ordered not to repeat it to the Soviets, nor to mention that the Americans had interrogated them first.[55] In April 1947, the War Department dispatched Norbert Fell, a biological weapons expert at Camp Detrick in secluded rural Maryland, the U.S. Army’s principal base for research on bioweapons—established in 1942 after reports of Japanese germ warfare in China.[56]

The U.S. government was eager to tap Ishii’s sinister knowledge. U.S. military intelligence and Major General Alden Waitt, a specialist in chemical warfare, took a keen interest in his interrogation. The War Department instructed Fell to ask Ishii about who had been involved in the program, how the laboratory had operated, what diseases and organisms had been studied, and whether the Japanese planned to use the agents by dropping bombs or spraying them from planes.[57] As a colonel at General Headquarters wrote in a top secret note, there was “great intelligence value” to the United States in learning more about “[h]uman experiments,” “[f]ield trials against Chinese,” and strategic and tactical uses of biological weapons, as well as the likely possibility that the Japanese general staff had known about and authorized the program. The Japanese had done battlefield trials against the Chinese army on at least three occasions. This General Headquarters colonel hoped that lower-level Japanese in Unit 731, who were somehow seen as not liable for war crimes, could provide “most of the valuable technical BW [biological warfare] information as to results of human experiments.”[58]

So far the captive officers of Unit 731 had talked out of a mixture of persuasion, fear of the Soviets, and hopes of ingratiating themselves with the Americans. Yet Ishii had admitted that he had superiors who had authorized his program and knew about it, as would be expected for a project of such size and sensitivity. Those higher-ranked Japanese officers, a colonel at General Headquarters noted, would want promises that they would not be prosecuted as war criminals before they would talk. (This colonel repeatedly wrote “war crimes” in quotation marks, downplaying the possibility of criminality or accountability.) Ishii tacitly confirmed that his unit had experimented on human beings, and offered to describe his program in detail if the United States would guarantee in writing immunity from charges of war crimes for himself, his superiors, and his subordinates. He added that he had extensive knowledge of biological weapons, including how to use them in the frigid climate of northern China—an unsubtle attempt to make himself useful for coming U.S. contests against the Soviet Union. Eager to learn more, General Headquarters wanted to assure the Japanese that their disclosures would be kept in intelligence channels, not to be used for evidence for war crimes trials.[59]

To find out if there was any evidence that might get in the way of immunity for Ishii and the others, the War Department urgently instructed the head of MacArthur’s legal section, Colonel Alva Carpenter, and Frank Tavenner, then the U.S. acting chief prosecutor at the Tokyo trial, to relay whatever material the U.S. government had against them. Were Ishii and his confederates among the remaining major Japanese war criminals awaiting an international trial, and were any other Allies planning to charge them?[60] Carpenter reassuringly replied to the War Department that his files on these Japanese biowarriors held nothing more than anonymous letters, unconfirmed allegations, hearsay affidavits, and rumors—not enough evidence to support charges of war crimes. Neither Ishii nor his associates were on the list of fifty or so major Japanese war criminals awaiting trial, and no other Allied countries had charged them so far. Still, several generals who had been Ishii’s superior officers were, including Tojo, who had been the Kwantung Army’s chief of staff in 1937 and 1938.

Tavenner warned that the Soviet Union would probably launch its own trials for Unit 731. During their conquest of Manchuria, the Soviets had captured two of Ishii’s subordinates, Major General Kawashima Kiyoshi and another officer, who were being held as presumed war crimes suspects. Kawashima’s affidavit to Soviet investigators, which the Tokyo prosecutors had on file, revealed that they had been secretly researching viruses for warfare and conducting experiments, on orders from the Japanese general staff. Another affidavit, from a Chinese doctor, accused Japanese planes of scattering infected wheat grains on four Chinese cities in 1940, causing outbreaks of bubonic plague. Still, Tavenner explained that the Allied prosecutors had ruled out adding these crimes to the charges against Ishii’s superiors on trial in Tokyo, due to insufficient evidence connecting Tojo and the others with Ishii’s secretive project.[61]

The War Department quickly pronounced itself satisfied that the evidence at General Headquarters would not warrant putting Ishii and his group on trial as war criminals, but wanted to know whether the prosecutors at the Tokyo trial thought that any evidence showed that Ishii’s operation had violated the rules of land warfare.[62] Of course, biological weapons violate the core principles of the laws of war: they cannot be aimed to avoid infecting civilians as well as soldiers, nor controlled to have a proportionate effect, and they are most likely to kill elderly people or children.[63] The Hague Convention IV on land warfare of 1907 forbade the use of poison and poisoned weapons, and in 1925, a League of Nations conference had created a Geneva Protocol prohibiting the use of chemical and biological weapons, which Japan had signed.[64] The fact that this top secret bioweapons facility was hidden away in remote Manchuria suggested that the Kwantung Army understood that its work was beyond the pale.

At the Tokyo tribunal, Tavenner and his prosecutors carefully reviewed the Unit 731 affidavits held by the Soviets. They concluded that Ishii’s biological weapons group “did violate rules of land warfare,” but wanted more corroboration and investigation before indicting him and his team for war crimes. Still, the Tokyo prosecutors knew in chilling detail about Japan’s biological warfare against Chinese cities. In October 1940, in an experiment by Unit 731, Japanese airplanes had scattered infected wheat grain over the port city of Ningbo; two days later, the city suffered an outbreak of bubonic plague that left ninety-seven people dead. There was strong circumstantial evidence, the prosecutors noted, of “bacteria warfare” in three other cities. At one, Japanese planes had scattered rice and wheat grains mixed with fleas; a month later, bubonic plague erupted. In November 1941, at Changde, in Hunan province, a Japanese plane had dropped wheat and rice grains, paper, cotton wadding, and mysterious particles; these caused several cases of what seemed to be bubonic plague. For use against the Chinese army in 1940, Ishii’s group had manufactured seventy kilograms of typhus, five kilograms of cholera, and five kilograms of plague-infected fleas. In 1942, Ishii had infected areas in central China with typhoid and bubonic plague bacilli, and in 1943 and 1944 he had overseen seven or eight experiments using anthrax and bubonic plague on Manchurians. By 1944, according to the prosecutors, Ishii’s team had accumulated tons of materials to cultivate these lethal bacilli in “preparation of mass production of bacteria.”

Such a vast, complex, and costly project would have almost certainly required approval from senior Japanese officials, not least for permission to bombard Chinese cities with biological weapons. Yet the U.S. prosecutors still claimed that they had not been able to prove links between the senior Japanese leaders on trial in Tokyo and the actions of the biowarfare group. Having decided to keep Unit 731 out of the Tokyo trial, the U.S. prosecutors’ review of the Soviets’ evidence made them worry that the Soviet prosecutor would try to cross-examine some of the witnesses and bring up some of this evidence.[65]

In the end, the Soviets chose to run their own show trial, which meant that they could keep the biowarriors in their custody while rebuking the United States. In December 1949, twelve Japanese officers would be swiftly convicted by a Soviet military tribunal in Khabarovsk, the largest Soviet city near Harbin.[66] In a Stalinist indictment raging against the “insane” anti-Soviet plotting of “imperialist Japan’s ruling clique,” these Japanese were accused of using “a criminal means of mass extermination of human beings.” One after another, all twelve Japanese defendants either said “I plead guilty” or “I fully plead guilty.” After just five days, the verdict treated the Soviet Union as the leading victim of Japan’s biowarfare program, commenting that the Tokyo trial had already established the centrality of anti-Soviet aggression in Japanese policy. On top of that, the Soviet prosecutors sought to implicate General Umezu Yoshijiro and Emperor Hirohito himself, claiming that the creation of bacteriological warfare units had been done on secret royal instructions.[67]

In contrast to the Khabarovsk drama, Unit 731 would remain invisible throughout the Tokyo trial. Although a Soviet colonel handled the prosecution’s cross-examination of the witnesses called on behalf of Umezu, he asked nothing about biological warfare.[68] Decades later, the failure to prosecute the Japanese involved in biowarfare is one of the gravest stains of the Tokyo trial. “Everything connected with it was kept from the tribunal,” Bert Röling, the Dutch judge, complained bitterly years later. The cover-up, he said, had “severely damaged” the authority of the Tokyo trial.[69] Ishii got his Japanese army pension and lived out his days in comfort.[70]