1908

The Tunguska Explosion

Leonid Kulik (1883–1942)

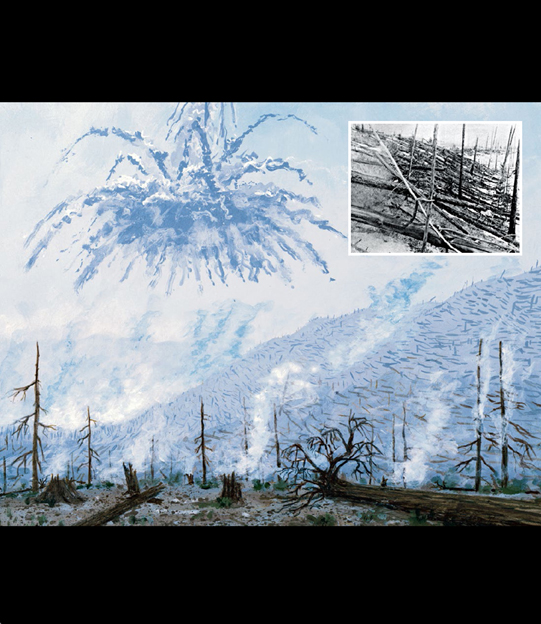

Many residents of remote central Siberia near the Tunguska River were startled awake on June 30, 1908, by a spectacular event. Around 7:15 a.m., the skies erupted in a blinding flash of light, followed by thunderous explosions. The ground shook with the force of a magnitude 5.0 earthquake. Farther away, a fierce hot wind and a rain of fire stripped and felled 80 million trees over more than 811 square miles (2,100 square kilometers)—an area half the size of Rhode Island. Seismic shocks from the event were recorded across Asia and Europe, and night skies around the world glowed with an eerie light for days afterward.

Scientists suspected that the region had experienced a meteoroid impact. The first scientific group to study the remote, uninhabited region where the event actually occurred didn’t arrive until 1927, however, when the Russian mineralogist Leonid Kulik searched in vain for the resulting impact crater. Apparently, the event was an airburst explosion, with surface damage caused by shock waves, heat, and fire—but with no associated crater formed like the one at Meteor Crater in Arizona.

Planetary scientists have debated the nature of the Tunguska impactor for more than a century. Was it an icy comet fragment that disintegrated catastrophically from atmospheric entry, or a small, rocky asteroid, perhaps a rubble-pile object that was too weak to survive all the way to the surface? Whatever its origin, the best hypothesis is that an object only about 33 feet (10 meters) across, traveling at around 6 miles (10 kilometers) per second, exploded around 6 miles (10 kilometers) above the surface with an energy of about 10 megatons of TNT—similar to that at Meteor Crater and more than 500 times the yield of a World War II atomic bomb.

A similar, though thankfully less energetic, fireball and airburst explosion occurred over the western Russian city of Chelyabinsk in 2013. Amazingly, no one was killed by the Tunguska or Chelyabinsk explosions (though many were injured by shattered glass in Chelyabinsk). Tunguska and Chelyabinsk are wake-up calls for understanding impact events, especially the catastrophic shock-wave effects that even small objects traveling at extreme speeds can have on our environment when they occasionally slam into our planet.

SEE ALSO Dinosaur-Killing Impact (c. 65 Million BCE), Arizona Impact (c. 50,000 BCE), The US Geological Survey (1879), Hunting for Meteorites (1906), Understanding Impact Craters (1960), Meteorites and Life (1970), Extinction Impact Hypothesis (1980)

Main image: Artist and planetary scientist William K. Hartmann’s impression of the Tunguska forest one minute after the airburst explosion. The painting was made at Mount St. Helens, where the 1980 blast from that volcano produced a Tunguska-like scene. Inset: 1927 photo from the Kulik expedition.