When I was at the market one day, I was happy to see a fresh whole red snapper, cheap because it was still uncleaned and unscaled. And there was some good local fennel, and some rose pink garlic. I had tomatoes at home. The sourdough bread had just been delivered to the store; it was still warm; I got some of that.

This is what we had for dinner:

Red snapper bouillabaisse w/large amounts of garlic and fennel.

Rouille.

Sourdough bread.

Goat cheese.

Red wine.

(We had it for lunch the next day, too, but this time over garlic rubbed sourdough toast.)

To make the soup (really more of a stew, it’s so thick):

Chop an onion finely, stew it in olive oil to cover the bottom of a pot.

Add a chopped chile pepper if you like heat.

A diced carrot.

A sliced fennel bulb.

As much garlic, chopped, as you like.

Some chopped parsley.

While this is going on, scale and clean the whole fish. Put the head and bones and trimmings into another pot, cover with water, throw in the carrot and onion ends, some whole garlic cloves (don’t need to peel them), bay leaf, fennel fronds . . . really, whatever you’ve got that will add flavor to the broth.

When the onion etc. is nice and stewed (don’t brown), add some wine (I had some red leftover, so added that), simmer till alcohol cooks off, add plenty of diced tomato (or canned tomato). Add some saffron if you have it—it makes a difference. Bring to brisk boil; boil about 2 minutes, then cook at a brisk simmer till nice and thick and tasty. Add salt. Strain fish broth—which should taste of all the things in it by now—into the veggie pot, and cook the whole thing until it tastes really good to you. About twenty minutes to a half hour should do it. Boil it down if the broth is too thin. Taste for salt again.

Make a rouille. That’s just garlic mayonnaise with saffron and red pepper added. I soak a dried pepper till it’s soft enough to mash with the other stuff, and use that.

Right before you serve dinner, put out some bread and cheese—goat cheese is great. Put soup plates into oven to warm. Chop some fennel fronds to use to garnish the soup. Warn companion that it’s time to light the candles and pour a couple of glasses of wine. Then add the filleted fish, cut into chunks, to the soup.

Don’t go away from the stove. The fish should take about two minutes to cook.

Serve the fennel strewn soup in the warmed plates; add rouille at pleasure; if only two of you and no children to impress with manners, scrape the last of the rouille out of the mortar you made it in with the last bits of the bouillabaisse soaked and goat cheese spread bread.

We get good salmon here, which is lucky, given our landlocked status. Somehow we’re on the salmon distribution trail that runs down from Alaska to the markets in California south of us, and since the fish is frozen on the boats just about as quickly as it’s caught, it’s the freshest we can hope for. Which is not bad at all.

Every year when the Growers’ Market starts up in the spring, we have some nice woman selling frozen salmon under one of the awnings. And I pretty much buy a couple of filets every week that I can. Growers’ Market day is errand day for me generally, and I don’t feel much like fussing over a meal when I get home. (Although as I write this, it occurs to me that I don’t much feel like fussing over a meal generally. I pretty much like a straightforward preparation during the cooking phase followed by sighs of contentment during the eating phase. Fussing doesn’t enter into it.) So Tuesday dinner during salmon season is generally: a.) salmon, b.) black rice/quinoa/or whole wheat couscous with butter and soy sauce added at will at the table, c.) appropriate vegetable and, d.) salad. Simple, easy, good to eat, good for you. Not particularly inexpensive, but a pretty good deal if you buy the fish from the nice lady selling it out of the cooler on the back of her truck at the Growers’ Market.

One of my favorite ways to cook the filets is à l’unilateral, topping them after with wasabi butter. Translated, this means the fish is cooked on the skin side only, till it’s nice and crispy and brown, and the salmon itself is tenderly underdone.

There are a lot of good recipes for this, but I tend to follow the counsel of Patricia Wells here. She recommends painting the skin side with some olive oil to keep it from sticking, then heating on medium heat a nonstick, preferably ceramic, pan.

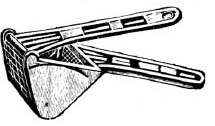

Add a tablespoon or so of butter to the pan, let it foam and subside, put the salmon in skin side down, and cook about 6 minutes or so, till the skin is nice and crispy and etc. (I use one of those screen thingies on top of the salmon to keep the grease from sputtering all over the stove.)

Then clap a lid on it and let it steam for a minute or two, but NO LONGER, till it looks done to your liking. (This timing is for thawed salmon, though if the fish manages to make it home still frozen, I just use it that way and allow a couple of extra minutes. This makes a very rare salmon, which I happen to think is salmon at its best, but if you like your fish well done, just leave it on the fire longer. Try it my way first, though.)

Sprinkle with flaked or coarse salt. Serve with wasabi butter melting on top.

For the wasabi butter: dead simple. If you have a mortar and pestle, do like I do. Grind some whole peppercorns and salt, then add as much butter as you want, as much wasabi as you want, and a little bit of soy sauce. Mash together till well mixed. If you don’t have a mortar and pestle, just mash everything, except the peppercorns, together with a fork in a bowl, and then add freshly ground pepper from the peppermill.

We had this the other night with room temperature asparagus dressed with a soy/ginger/garlic/scallion sauce left over from a tofu dinner the night before. Steamed black rice, which is particularly nice with salmon. Lemon wedges. And after, a salad tossed with a lemon/thyme dressing with a touch of blue cheese smushed in. I don’t know why, but blue cheese—just a little, anyway—always seems to go with soy sauce . . . and it’s really nice after the wasabi.

As for why we have the salad after . . . sometimes we have it before, sometimes after. The real deciding factor is whether the main course needs attending to by the cook right up until it demands to be eaten. Since we have that salmon just about the minute it gets off the stove and under the melting wasabi butter, I generally have the salad on the table waiting to be tossed and served out after. (Dressing at the bottom of the bowl, crossed serving implements on top, salad leaves piled on them over the dressing . . . so the salad doesn’t get all wilted and depressed while we’re eating everything else.)

Also, if we’ve just had something that will taste good with the salad scooping what’s left, it’s nice to serve it on the same plates. I like that with the salmon. What’s left of the wasabi butter, and the soy sauce from the asparagus, just mingles with the salad in a harmonious kind of way.

I was hardcore about getting over the stomach flu.

My first trip back to the market—shopping for my first real meal (i.e. one that didn’t consist mainly of brown rice porridge)—and I found myself mooning over a bunch of live mussels. Also craving whole wheat bread, of the kind made into a whole, unsliced, rough and ready loaf. Go figure. But I really wanted those mussels, and so they went into the cart along with the bread, and some mesclun leaves for salad. I was also craving blue cheese in my salad dressing. Don’t ask me why, unless it’s that I permanently crave blue cheese, which is a distinct possibility.

The great thing about mussels is that they are, a.) relatively inexpensive, b.) light on the stomach, c.) incredibly fast and easy to cook. I like all these things.

So this is what I did with them, a little more than a pound unshelled, enough for us two for dinner, though you might want to have them as an appetizer if you’re feeling really hungry.

First I gave them a rinse and gently lowered them into a bowl of salted cold water. You can let them sit like this for a day in the refrigerator, if you have to. You can add flour if you want them to have a little something to nosh on while they wait.

Then I warmed some olive oil and butter (just a tablespoon or so) in a big heavy casserole. I minced a little onion, a garlic clove, and a few sprigs of parsley and warmed them up in the oil until the onion was golden. I added about four chopped Roma tomatoes, a small glass of white wine, a bay leaf, a sprig of fresh thyme, a little saffron . . . and, discovering some Pernod in the back of my cupboard, a slosh of that. I cooked all of this pretty briskly for about fifteen minutes till it was nice and sauce-like, then tasted for salt and added a little.

Then I drained the mussels and put them in the pot with the sauce, still over a good medium flame. Clapped the cover on them.

While they cooked—these were good tiny ones, and only took around five minutes—I sliced some of the bread, put it and the butter on the table, and poured myself a timid glass of white wine. Checked the mussels. They were all opened up and smelling tomatoey and of the sea in an appetizing way. I was pleased at the appetizing part. I was beginning to feel like myself again.

Served the mussels in bowls; we mopped the sauce up with the bread, and then had a salad with blue cheese and lemon juice dressing in the bowls to mop up what the bread didn’t get.

The wine felt lovely, to my delicate stomach’s surprise. And my only regret was that I hadn’t thought to add a slice of orange peel to the sauce—it would have been a nice flavor with the saffron and the Pernod and the thyme. And once I’m worrying about that kind of thing, well, I know I’ve left the stomach flu way behind.

There were more mussels at the market a few days later, looking bigger and hairier than the ones I bought before, but still appetizing, and by far the best deal and the freshest in the fish section. Also, Ken had just delivered my favorite sourdough bread to the store, so that it was still warm and quite irresistible. Also, I had exactly an hour from when I was due to get home to when I was due to go out again, so I needed something really quick and easy for dinner.

I thought about it all the way home, how to cook them this time, and I contemplated several different ways: with beer? with olive oil and garlic? with pesto from the freezer? But then the car did a slight, treacherous skid on the snowy road, and I remembered (I always need that first reminder every year) that it was winter and I had better slow down. So I thought about the easiest possible way I could cook them, and the most satisfying for a snowy winter’s night.

This is what I did with them (for two people):

Put a little more than a pound of mussels in a bowl of salty water. This batch had beards on them (sometimes the fishmonger trims them off before packaging them; not this time, though), but I never take the beards off till right before cooking, since it kills the shellfish pretty fast. So I let them sit while I heated a little butter (about a tablespoon and a half) in the big enameled cast iron pot. I stewed a minced large shallot in the butter, and added a tablespoon of curry powder, too. Then I diced a Roma tomato and threw that in with a large glass of white wine. I let that cook down, salted it, added a little cream—just a slurp from the carton—and while that was heating, pulled the beards off the mussels. Then I put them in the pan in the midst of the bubbling sauce, clapped the lid on, and sliced some bread. Also toasted some pecans and crumbled some blue cheese into a bowl on top of them, with a couple of handfuls of mesclun lettuce. Set the table, put out the butter, poured myself a glass of wine, and the mussels were ready, all in about five minutes.

I sprinkled parsley on top of the mussels and spooned them into a couple of bowls. We ate them with the bread to mop up the sauce, and when we were finished, I tossed the greens and pecans and blue cheese first with a little olive oil and salt and pepper, and then with a tiny bit of sherry vinegar. We mopped up what was left in the bowls with the salad. And it was a very nice dinner indeed.

Mussels are great to eat around the holidays. They save you money, they save you time, they save you calories you can spend on Christmas chocolates instead, and they have a sort of festive atmosphere about them that’s quite nice for the season.

And I even had time, before I went out, to salt some cod I’d bought for a Christmas Eve brandade de morue. That would take a little longer to cook, and it’s a little more expensive, too, but satisfying in its own way. Very satisfying.

They grow these fabulous oysters on the Oregon coast, and we order them, of course, whenever we’re lucky enough to be in a restaurant serving them up. I used to deeply regret that I couldn’t get my hands on the same oysters myself.

But then one day, just out of the blue, my local Co-op started selling the very same oysters, shucked and nestled in their own juices. No hesitation when I saw them—I pounced. And had them that night, scalloped.

This is how:

For half a pint of oysters, which will feed two, make about a cup and a half of breadcrumbs. Sauté these in a couple of tablespoons of butter till golden. Mix breadcrumbs with minced parsley, minced garlic, minced scallions. (If you have a Cuisinart, first whirl the bread crumbs—crustless—then, while they’re frying, whirl the parsley, garlic, and scallions.) Mix the parsley mixture with the cooled crumbs. Salt and pepper. Butter a shallow casserole dish—not very big, just enough to hold two layers of crumbs and one of oysters. Then layer half the crumbs, the oysters, sprinkle oysters with salt and pepper, layer the rest of the crumbs. Dribble cream on top, about two tablespoons. If you don’t have cream, melt some more butter and dribble that. Bake in a 350° oven for about 25 minutes, till it looks golden and heavenly and smells of oysters. Serve with a salad made with a mustard vinaigrette in which you’ve marinated a sliced stalk of celery. White wine.

Heaven. And I didn’t even have to leave the house.

For years now, the only canned tuna I’ve bought is one that caught my eye, one day, on the grocery shelf.

Its label was a plain white strip of paper with simple black lettering that said: “Fishing vessel Pisces Albacore. Product of USA. Contents: Albacore. Sea Salt.” And on the back: “You are holding North Pacific Albacore Tuna, hook and line caught by the fishing vessel Pisces, then hand packed by a quality Oregon micro-cannery. Our albacore is filleted and canned with no additives except 15 grams of sea salt. This product is humanely harvested with no accidental capture of other species. Dolphins play at the bow while we fish!”

A hand drawn picture of a blue tuna holding a red heart was on the side.

It was, and is, at $4, an expensive can of tuna (although less now than when I first started buying it—now it seems a very reasonable price for almost half a pound of toxin free omega-3 fish). I started buying it because I was worried about mercury levels in most canned fish, and vaguely remembered that wild caught tuna from Pacific Northwest waters showed negligible levels of the stuff. Also, that sentence about the dolphins, with its final exclamation mark. Something about the whole label spoke to me of real people with a real job, working a small business their way.

Anyway, I bought it.

Once we’d tasted it, we never went back. There was no comparison between what came out of that can and Chicken of the Sea. Big meaty pieces of filet, with a hearty, honest taste to them. Everything I made with that tuna—and once I’d tasted it, I treated it with the respect it deserved—tasted like a party. Tuna and lentil salad with pita bread. Tuna sandwiches made with sourdough bread and aioli. Just the tuna by itself tossed with olive oil and lemon juice, on top of a bed of greens. It was all great. And it was all more than worth the money. From time to time, I wondered about that label, and about the people behind it. I wondered where they fished and how they fished, and, more importantly, why. Most of the time, though, I just enjoyed their tuna. I paid attention to it. It insisted, by its very integrity and taste that I pay attention to it. Which is what I want from my ingredients whenever I set out to make a meal.

Then, one day, I was shopping at my local Co-op, and passed a minor hubbub going on at the counter where they usually showcase products and give out samples. As I passed by, thinking about something else (goat cheese, as I recall, and whether Ken had arrived yet with the day’s shipment of just baked bread), my eye was caught by a pyramid of the cans of what I by now thought of as My Tuna.

“Ah!” I said, skidding to a halt, “My Tuna! I’ve been buying that for years!”

Then I noticed her behind the cans. She was a little worried looking, and a little worn, but she had those sparkling eyes you read so much about. They sparkled now, and darted and shone. “That’s MY tuna you’ve been buying,” she said proudly. “And I’m so glad to meet you. I always wonder about our customers on the other end.”

After assuring her enthusiastically that I had often wondered about her as well, and heartily praising her tuna, I finally got to ask: “Who made that label?”

“I did!” she said, and she laughed again. “I drew the fish! I was so proud of that fish! I’m glad you liked it!’

Then, as often happens, we settled down to talking. And she told me her story.

“When I was in school out on the coast, I started doing temp work going out on the fishing boats in the summer. Well, you know how it is. I fell in love with one of the guys, and we got married, and then we had our own boat. And we worked and worked and worked—you have no idea how hard we worked—but we just couldn’t make it pay. Too much competition from the big boys. It was just too hard. So I finished my nursing degree, and we moved inland close to here. I liked it there, had a nice job, and he went into construction. Everything was fine, I thought.

“Then, I don’t know what happened, whether it was a mid-life crisis, or what, but one day my husband just woke up and said, ‘I’m sorry. I have to go back to fishing. That’s what I have to do.’ I thought to myself, well, this is just a phase he has to go through. He’ll get over it. So I kept the house here and my job, and watched him move back to the coast and buy another boat. I’d commute out to keep him company—you know that drive’s beautiful, but it’s a long one. And after a couple of years, it dawned on me. This wasn’t a mid-life crisis. And it wasn’t going to go away.

“But I probably still would have stayed here, except that a friend of ours, a guy that fished from Alaska on down, who really knew what he was doing, went out one day alone in his boat and disappeared. They found parts of his boat floating later, but no one ever knew what had happened, whether there’d been some kind of explosion or what. And I said to my husband, ‘Well, that’s it. You’re never going out on a boat alone again. I’m coming with you, and whatever happens to you will happen to me, too.’ So I sold up the inland house and moved out and we went back to fishing.”

Fortunately, this time the timing was right: shoppers were more aware of how hard the larger fleets were on the environment, on dolphins especially, and how the tuna packed by big business was frequently of inferior quality. This time, while it was still hard, they found they could make the fishing pay. But of course, if you’ve got a small business, you can’t just fish. You’ve got to go out and sell your fish. And that’s what she was doing today.

She gave me one of their pamphlets, with a picture of her standing, grinning widely, dressed in oilskin, holding up an enormous tuna. And I noticed there was no website, no email address, just phone numbers. I didn’t ask her about that. I could just imagine, along with everything else they had to do, how impossible it would be to have a web presence as well. And somehow I found that a very comforting thought. The people who caught my tuna were too busy in the real world to worry much about the virtual.

We parted with warm expressions of esteem—and me with another couple of cans of tuna in my shopping cart. And I thought about her again the other night, during a heat wave, when I made a tuna niçoise pasta salad so good that my husband and I both sat there with our glasses of rosé just staring at it between bites. Not for long, though, since it was gone fast.

This was how, for two people for dinner, with a little left over that got doctored for a great lunch the next day:

In a colander in the sink, I put four diced Roma tomatoes, a half a sliced yellow onion, a chopped scallion, and a julienned jalapeno pepper. Tossed these with a tablespoon of coarse salt, covered with a plate and weighted it down to push out any bitter juices. I let those sit for a half an hour or so while . . .

In a big salad bowl, I put four halved anchovy fillets, a few chopped capers, about twelve pitted and torn Kalamata olives, a half a bunch of parsley minced, two quartered hard boiled eggs, and a can of Pisces tuna, broken into chunks. I squeezed a little lemon over this and tossed.

I put a pot on to cook a quarter pound of ziti pasta.

And made the salad dressing:

In a mortar, five cloves of garlic, the rest of the can of anchovies, some pepper, a little salt, the oil from the can of anchovies. I mashed all of this to a puree, then added red wine vinegar to taste.

Rinsed the salted vegetables in the colander and let them dry out a little while I cooked the pasta. Then added the vegetables to the salad bowl, drained the pasta in the colander, refreshed and cooled it with cold water. Shook the extra water off, then added it to the salad bowl with the rest of the ingredients, and the salad dressing.

Tossed very gently so as not to mash the eggs too much.

Served on a bed of spring greens, with lemon wedges on the side.

(The next day, for the bit that was left, I added two grated carrots, another chopped scallion, some more minced parsley, some lemon juice and olive oil, and tossed the whole with a good amount of lettuce. We had that on top of whole wheat tortillas, topped with a little Greek yogurt, and a very good lunch it was, too.)

There’s really something different about cooking and eating food made by people you’ve met in circumstances you can understand. It makes you feel more closely knit into the social fabric, and it makes you feel less alone. And of course, by paying a little more, you’re helping to reweave that social fabric, not just standing by helplessly watching it unravel. Not to mention how much better everything tastes when you sit down to dinner with your loved ones.

To order Pisces Tuna, contact Sally and Daryl Bogardus, PO Box 812, Coos Bay, Oregon, 97420, USA. Phone numbers: (001) 541-266-7336, or the cell phone (001) 541-821-7117. (They have smoked albacore and various gift packs. I’ve tried the albacore myself. It’s really good with lentils, or mixed in a potato salad.) [For an update on Sally, Daryl, and Pisces Tuna, go to p. 224 ]

We had an anniversary coming up, and usually this means either a quiet trip to the beach with the dogs, or dinner at our favorite local restaurant. But this time, we both felt more like staying home. Too little cash, too little time, he’d been traveling too much to want to get in a car again . . . and I just went four hours away and four hours back with our young dog to rescue another dog from an animal shelter where she was unable to find a home. We wanted to stay with the dogs, too—the new dog was so tentatively thrilled to be here, safe and sound and among friends, who could bear to lock her up in a car while we ate inside?

So I wanted to make something festive for dinner, but not something that would involve a lot of fuss. Something that would let me settle down in front of the fire with my loved ones while it cooked. Normally, this would mean my version of paella. But I didn’t really have the time or the money to race around looking for the best seafood and sausage to put into it. That left an arroz, my version of a Spanish rice dish, made with whatever bits and pieces I could find. Bits and pieces in Spanish is “pedacitos.” So Arroz con Pedacitos. With aioli, to really dress it up and make it particularly nice.

The guys at my local Co-op fish counter know when they see me coming that I’m going to scour the shelves for whatever they’ve got of fish scraps, packaged and sold cheap. I buy them when I see them, and toss ‘em in the freezer against just such a need as this one. So I had a couple of packages of halibut frames, with a good amount of fish still clinging to the nicely gelatinous bones—$1.99 a pound. And I had a yogurt container full of fish stock in the freezer, made the last time I put together an arroz.

Fish stock—any kind of stock—is easy if you don’t worry yourself too much about it. Just throw what non oily fish scraps and bones, along with shrimp shells (when you eat shrimp, don’t throw out the shells left on the plate, decant them into a plastic bag and freeze them for making stock later), in a saucepan along with a cleaned carrot (or peelings), a stick of celery (or peelings—if you have them), a bit of onion or top of a leek, an unpeeled garlic clove or two, a bay leaf, some peppercorns, and sprigs of parsley and/or thyme.

Don’t worry if you don’t have some of this, or if you have other things instead that might make it taste nice—fennel fronds, say, or chard ribs, or a little bit of lemon peel. Just imagine what the combination would taste like and add, then cover with water. Bring to a boil. Simmer for about a half an hour, then take out the fish skeletons and shred what fish there is on the bones into a bowl. Set aside. Put the bones back in the stock and simmer some more, until the liquid tastes nice. At this point, you can freeze it, or keep it simmering to add to the arroz.

Of course if you have it in the freezer already—and luckily, this time, I did—the dish is a breeze. I just heated up the stock, added the fish skeletons, cooked till the fish on them shredded, took them out, saving the fish—and that was my nicely deepened stock. While that was cooking, I made the aioli. If you make it in the food processor or the blender—one whole fresh egg whipped with some salt, one cup of olive oil added SLOWLY, then mixed with at least five pureed garlic cloves and a little lemon juice—it takes hardly any time at all. And it’s so delicious, it makes us scrape the plate with our fingers to get the last bit up. We can do this when it’s just the two of us, which is one reason why eating at home is so delightful. That, and that we can eat in our bathrobes if we feel like it.

Now the arroz. For two, with leftovers for next day’s lunch:

Get a wide pot or skillet out, one with a good fitting lid. Pour in a little olive oil—Spanish is nicest for this. Heat gently, and sauté a chopped onion until it’s soft. Add a few chopped cloves of garlic (or just one, if you’re not as crazy about garlic as we are) and a minced hot pepper. Cook for awhile on the lowest heat till everything’s soft but not browned, almost melting together. Salt. Then add a teaspoon and a half of pimenton de vera—Spanish smoked paprika. Stir so it doesn’t scorch. Add a diced tomato or two, and continue cooking on a low heat until the whole thing is like savory jam.

While this is going on, soak a couple of pinches of saffron in a little bit of wine. (I also use this time to make a salad dressing for our first course, and to set the table.)

Now. Add 1½ cups short grain BROWN RICE. Really. Please try it. It tastes divine, really meaty and much more interesting than that upper class white stuff you’ve been using. Yes, I know it takes longer, but so what? That’s just more time to sit with your loved one and a glass of wine, isn’t it? And this is a festival after all.

Stir the rice until it crackles. Now add 4 cups of simmering fish stock. Maybe a little more salt at this point—taste. Bring back to a boil, add the wine and saffron, clap the lid on, turn the heat onto the lowest setting, and set the timer for an hour. (You’ll have to check from time to time till you get used to the heat of your own burners. If it’s boiling too quickly, even on the lowest heat, use a flame tamer. That’s what I do, but my burners burn hot. On the other hand, if the rice isn’t tender in an hour, and there’s still liquid, take the lid off, turn the heat up a bit, and watch it till it’s near done, then clap the lid back on, turn the heat down, and let it go another five minutes.)

Use the hour to pour yourself and loved one a glass of something, and sit down with a few olives to nibble on. I had a bottle of inexpensive Spanish Rosé Cava all ready to go, and go it did.

We had a glass or two of that, and a pre-prandial wander ‘round the meadow in the dusk with the dogs, and when the timer went off, I had a look at how the rice was doing. When it was nearly done, I added the reserved fish bits, and some frozen peas straight from the package for color . . . maybe a drained jar of artichoke hearts I had sitting in the cupboard . . . then I let it cook another few minutes until it smelled wonderful. We sat down to a salad while I let the arroz rest a little off the heat. Then out it came, spooned in a beautiful bronzed pool onto white plates with a dollop of aioli and lemon wedges on the side. More aioli on the table. And more Cava of course.

That’s my idea of a fiesta. Really. (Oh, and for dessert, slices of quince paste, if you can find it, alternating with slices of Monterey Jack cheese. Eat a bit of both in one bite. It sounds weird, but it’s completely creamy and delicious, and the whole is more than the parts . . . which, come to think of it, was what we were celebrating on our anniversary, too.)

We used to have paella for Christmas. I liked the thought that octopus was a traditional holiday ingredient in our house. And I have spent many years perfecting a paella made with brown rice. We’d have it with a blue cheese and walnut dressed salad beforehand, and lots of red wine. Delicious.

Until a few years ago, when I realized it was silly to buy fresh seafood on Christmas Eve and keep it overnight just for some kind of formal celebration. I mean, when you have fresh seafood, you should eat it. That’s one of the few rules I live by, or should, anyway. So we shifted, and now have our paella the night before.

This left me with a dilemma. How to make another quasi-vegetarian celebratory meal on the day itself. So we’ve had stuffed Portobello mushrooms. We’ve had oyster stew (really good that). We’ve had a lavish cheese platter.

This year, during a bout of pre-Christmas insomnia, which I spent, as usual, poring over my cookbook collection, I suddenly thought: “Brandade. Brandade. Definitely Brandade.”

Brandade being mashed potatoes if mashed potatoes had gone first to sea and then to heaven . . . being mashed potatoes and mashed salt cod mashed with cream and olive oil and lots and lots of garlic. (I try to eat it whenever I’m in Paris. I’ve discovered a couple of nice little restaurants that way, by noticing it marked on a blackboard as the special of the day—salt cod on the menu being, as I think, a sign of serious culinary intent.)

But where to get the salt cod? We don’t live, let me tell you, near a salt cod kind of a town. No Portuguese or Italian delis for miles. But then I had one of those moments where you suddenly realize you’ve been roaming the world for the Pearl of Great Price, and all the time it was sitting on your desk, forgotten, used as a paperweight. We get a lot of Alaskan cod here this time of year, and I always ignore it. Not anymore. Salting cod, it turns out, is easy. Why I never did it before I’m sure I can’t think.

So this is what I did:

A few days before Christmas (salt cod keeps for ten days, if you keep salting it), I bought a little more than a pound of cod. I got a glass pan big enough to lay it out flat in, and sprinkled about a quarter cup of coarse salt on the bottom, laid the cod on top, and sprinkled another quarter cup of salt on top. Covered it with plastic wrap, popped it in the fridge. Every twelve hours, I just poured off whatever liquid accumulated and sprinkled a little more salt on.

Twenty-four hours before I wanted to cook it, I rinsed the cod and laid it in fresh water, which I changed two or three times. That was it—salt cod. So then I was ready for my brandade.

I checked every recipe I had in the house—you’d be surprised how many brandade recipes it turns out you probably have lurking about—and noticed that every one said their way was the only one. But every way was a different one. Now what that says to me is that the dish is pretty much indestructible, so I was pretty confident that I could set about doing it my way, unharmed.

Let me say that brandade, made with less oil and cream than your general recipe recommends, baked till it browns on top or until you feel like eating it, whichever comes first, turns out to be an absolutely celestial, celebratory, irresistible dish of the kind that you can convince yourself your imaginary French great aunt used to make.

So this is how:

Put one pound desalted salt cod cut in big pieces into a large pot, big enough to hold it all in one layer. If you have them about, put carrot and celery trimmings, a bay leaf, a garlic clove, and a sprig of thyme in with the cod. (Don’t fuss if you don’t. I happened to be making crudités to go with our first course, so just threw the peelings in as I went. It would have been even better if I’d simmered the water with the peelings first, then let it cool, THEN added the cod. But it was just fine the way it was.) Bring slowly to a low simmer, just to where bubbles start to show a boil. Turn off the heat. Clap on a lid and let it sit for fifteen minutes.

Meanwhile, peel a large potato, quarter it, cover it with water and simmer for fifteen minutes or until tender when pierced by a fork. Peel some garlic cloves. Two if you are a moderate garlic eater, or, if you’re like us, six. I highly recommend six.

Also, have a third of a cup of olive oil sitting on the stove in a Pyrex cup. And about three tablespoons of cream in another one. The point of this is to warm them, taking the chill off, so they’ll mix better later. Most recipes say to warm them in separate pans, but I find it’s easier just to put them near warm places. You don’t want them hot, just tepid.

When the cod is done, scoop it out and lay it on a plate till it’s cool enough to handle, and you can feel it to get out any little bones that might still be lurking. Get them all out.

Now put the garlic cloves and some pepper into a Cuisinart or blender. Get them nice and pureed. Add the salt cod and the drained cooked potato. Blend to as smooth or chunky as you like, or, if you’re using a food processor, pulse to mash. Add the oil and cream in a stream while you pulse.

The brandade should look like mashed potatoes.

Taste. Heavenly, eh?

Now you have some choices. You can serve as is with crudités as a dip. You can decant into a warm bowl, surround with garlic rubbed toasts, and serve as a first course. Or, you can do what I did . . . which I am now sure is the very best thing to do.

Decant the brandade into a nice heatproof bowl. When you’re ready, drizzle some more cream on top and put it into a 350° oven for about twenty minutes or so. If you like, you can stick it under the broiler for a minute to get it good and browned.

For some reason, putting it into the oven made my brandade puff up like a cloud. We had our first course by the fire, with champagne, while it cooked, and then came to table to have the brandade itself with a salad, some garlic rubbed toast, and more champagne.

This was about as festive a dinner as it gets. And now, our traditional Christmas foods are not just boring old octopus and squid. Not anymore.