VI. The Battle of the Aisne

The hazardous crossing of the Aisne—Wonderful work of the sappers—The fight for the sugar factory—General advance of the Army—The 4th (Guards) Brigade’s difficult task — Cavalry as a mobile reserve—The Sixth Division—Hardships of the Army—German breach of faith—Tâtez toujours —The general position—Attack upon the West Yorks — Counter-attack by Congreve’s 18th Brigade—Rheims Cathedral — Spies—The siege and fall of Antwerp

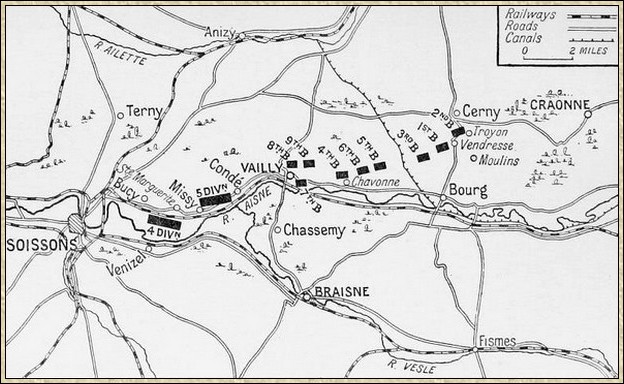

The stretch of river which confronted the British Army when they set about the hazardous crossing of Aisne was about fifteen miles in length. It lay as nearly as possible east and west, so that the advance was from south to north. As the British faced the hazardous river the First Army Corps was on the right of their line, together with half the cavalry. In the centre was the Second Corps, on the left the Third Corps, which was still without one of its divisions (the Sixth), but retained, on the other hand, the 19th Brigade, which did not belong to it. Each of these British corps covered a front of, roughly, five miles. Across the broad and swift river a considerable German army with a powerful artillery was waiting to dispute the passage. On the right of the British were the French Fifth and Seventh Armies, and on their left, forming the extremity of the Allied line, was the French Sixth Army, acting in such close co-operation with the British Third Corps in the Soissons region that their guns were often turned upon the same point. This Sixth French Army, with the British Army, may be looked upon as the left wing of the huge Allied line which stretched away with many a curve and bend to the Swiss frontier. During all this hurried retreat from the Marne, it is to be remembered that the Eastern German armies had hardly moved at all. It was their four armies of the right which had swung back like a closing door, the Crown Prince’s Fifth Army being the hinge upon which it turned. Now the door had ceased to swing, and one solid barrier presented itself to the Allies. It is probable that the German preponderance of numbers was, for the moment, much lessened or even had ceased to exist, for the losses in battle, the detachments for Russia, and the operations in Belgium had all combined to deplete the German ranks.

The Belgian Army had retired into Antwerp before the fall of Brussels, but they were by no means a force to be disregarded, being fired by that sense of intolerable wrong which is the most formidable stimulant to a virile nation. From the shelter of the Antwerp entrenchments they continually buzzed out against the German lines of communication, and although they were usually beaten back, and were finally pent in, they still added to the great debt of gratitude which the Allies already owed them by holding up a considerable body, two army corps at least, of good troops. On the other hand, the fortress of Maubeuge, on the northern French frontier, which had been invested within a few days of the battle of Mons, had now fallen before the heavy German guns, with the result that at least a corps of troops under Von Zwehl and these same masterful guns were now released for service on the Aisne.

The more one considers the operation of the crossing of the Aisne with the battle which followed it, the more one is impressed by the extraordinary difficulty of the task, the swift debonair way in which it was tackled, and the pushful audacity of the various commanders in gaining a foothold upon the farther side. Consider that upon the 12th the Army was faced by a deep, broad, unfordable river with only one practicable bridge in the fifteen miles opposite them. They had a formidable enemy armed with powerful artillery standing on the defensive upon a line of uplands commanding every crossing and approach, whilst the valley was so broad that ordinary guns upon the corresponding uplands could have no effect, and good positions lower down were hard to find. There was the problem. And yet upon the 14th the bulk of the Army was across and had established itself in positions from which it could never afterwards be driven. All arms must have worked well to bring about such a result, but what can be said of the Royal Engineers, who built under heavy fire in that brief space nine bridges, some of them capable of taking heavy traffic, while they restored five of the bridges which the enemy had destroyed! September 13, 1914, should be recorded in their annals as a marvellous example of personal self-sacrifice and technical proficiency.

Sir John French, acting with great swiftness and decision, did not lose an hour after he had established himself in force upon the northern bank of the river in pushing his men ahead and finding out what was in front of him. The weather was still very wet, and heavy mists drew a veil over the German dispositions, but the advance went forward. The British right wing, consisting of the First Division of the Aisne. First Corps, had established itself most securely, as was natural, since it was the one corps which had formed an unbroken bridge in front of it. The First Division had pushed forward as far as Moulins and Vendresse, which lie about two miles north of the river. Now, in the early hours of the 14th, the whole of the Second Division got over. The immediate narrative, therefore, is concerned with the doings of the two divisions of the First Corps, upon which fell the first and chief strain of the very important and dangerous advance upon that date.

British Advance at the Aisne

On the top of the line of chalk hills which faced the British was an ancient and famous highway, the Chemin-des-Dames, which, like all ancient highways, had been carried along the crest of the ridge. This was in the German possession, and it became the objective of the British attack. The 2nd Infantry Brigade (Bulfin’s) led the way, working upwards in the early morning from Moulins and Vendresse through the hamlet of Troyon towards the great road. This brigade, consisting of the 2nd Sussex, 1st Northamptons, 1st North Lancashire, and 2nd Rifles, drawn mostly from solid shire regiments, was second to none in the Army. Just north of Troyon was a considerable deserted sugar factory, which formed a feature in the landscape. It lay within a few hundred yards of the Chemin-des-Dames, while another winding road, cut in the side of the hill, lay an equal distance to the south of it, and was crossed by the British in their advance. This road, which was somewhat sunken in the chalk, and thus offered some cover to a crouching man, played an important part in the operations.

Lieutenant Balfour and a picket of the 2nd Rifles, having crept up and reconnoitred the factory, returned with the information that it was held by the Germans, and that twelve guns were in position three hundred yards to the east of it. General Bulfin then—it was about 3:30 in the morning of a wet, misty day—sent the 2nd Rifles, the 2nd Sussex Regiment, and the 1st NorthamptonS forward, with the factory and an adjoining whitewashed farmhouse as their objective. The 1st North Lancashires remained in reserve at Vendresse. The attacking force was under the immediate command of Colonel Serocold of the Rifles. The three advanced regiments drove in the pickets of the Germans, and after a severe fight turned the enemy out of his front trench, A Company of the Sussex capturing several hundred prisoners. A number of men, however, including Colonel Montresor and Major Cookson, were shot while rounding up these Germans and sending them to the rear. The advanced line had suffered severely, so the North Lancashires were called up and launched at the sugar factory, which they carried with a magnificent bayonet attack in spite of a fierce German resistance. Their losses were very heavy, including Major Lloyd, their commander, but their victory was a glorious one. The two batteries of the enemy were now commanded by machine-guns, brought up to the factory by Lieutenant Dashwood of the Sussex. The enemy made a brave attempt to get these guns away, but the teams and men were shot down, and it was a German Colenso. The British, however, unlike the Boers, were unable to get away the prizes of their victory. The factory was abandoned as it was exposed to heavy fire, and the four regiments formed a firing-line, taking such cover as they could find, but a German shell fire developed which was so deadly that they were unable to get forward.

A small party of Rifles, under Cathcart and Foljambe, clung hard to the captured guns, sending repeated messages: “For God’s sake bring horses and fetch away these pieces!” No horses were, however, available, and eventually both the guns and the buildings were regained by the Germans, the former being disabled before they were abandoned by their captors, and the factory being smashed by the shells. Major Green and a company of the Sussex, with some of the Coldstream under Major Grant, had got as far forward as the Chemin-des-Dames, but fell back steadily when their flank was finally exposed. Two companies of the 1st Coldstream, under Colonel Ponsonby, had also pushed on to the road, and now came back. Nothing could exceed the desperate gallantry of officers and men. Major Jelf, severely wounded, cheered on his riflemen until evening. Major Warre of the same regiment and Major Phillips rallied the hard-pressed line again and again. Lieutenant Spread, of the Lancashires, worked his machine-gun until it was smashed, and then, wounded as he was, brought up a second gun and continued the fight. Major Burrows rallied the Lancashires when their leader, Major Lloyd, was hit. Brigade-Major Watson, of the Queen’s, was everywhere in the thick of the firing. No men could have been better led, nor could any leaders have better men. A large number of wounded, both British and Germans, lay under the shelter of some haystacks between the lines, and crawled slowly round them for shelter, as the fire came from one side or the other—a fitting subject surely for a Verestschagin!

Meanwhile, it is necessary to follow what had been going on at the immediate left of Bulfin’s Brigade. Maxse’s 1st Brigade had moved up in the face of a considerable fire until it came to be nearly as far north as the factory, but to the west of it. The 1st Coldstream had been sent across to help the dismounted cavalry to cover Bulfin’s right, since the main German strength seemed to be in that quarter. The 1st Scots Guards was held in reserve, but the other regiments of the 1st Brigade, the 1st Black Watch and the 1st Camerons, a battalion which had taken the place of the brave but unfortunate Munsters, lined up on the left of the factory and found themselves swept by the same devastating fire which had checked the advance. This fire came from the fringe of the woods and from a line of trenches lying north-east of the factory on the edge of the Chemin-des-dames. Up to this time the British had no artillery support on account of the mist, but now Geddes’ 25th Brigade R.F.A., comprising the 113th, 114th, and 115th Batteries, was brought to its assistance. It could do little good in such a dim light, and one battery, the 115th, under Major Johnstone, which pushed up within eight hundred yards of the enemy’s position, was itself nearly destroyed. The 116th R.F.A., under Captain Oliver, also did great work, working its way up till it was almost in the infantry line, and at one time in advance of it. The whole infantry line, including a mixture of units, men of the Rifles, Sussex, and North Lancashires, with a sprinkling of Guardsmen and Black Watch from the 1st Brigade, came slowly down the hill — “sweating blood to hold their own,” as one of them described it—until they reached the sunken road which has been already mentioned. There General Bulfin had stationed himself with the reserve, and the line steadied itself, re-formed, and, with the support of the guns, made head once more against the advancing Germans, who were unable to make any progress against the fire which was poured into them. With such spades and picks as could be got, a line of shallow trenches was thrown up, and these were held against all attacks for the rest of the day.1

It was the haphazard line of these hurriedly dug shelters which determined the position retained in the weeks to come. As this was the apex of the British advance and all the corps upon the left were in turn brought to a standstill and driven to make trenches, the whole line of the First Corps formed a long diagonal slash across the hillside, with its right close to the Chemin-des-dames and its left upon the river in the neighbourhood of Chavonne. The result was that now and always the trenches of the 2nd Brigade were in an extremely exposed position, for they were open not only to the direct fire of the Germans, which was not very severe, but to an enfilading fire from more distant guns upon each flank. Their immediate neighbours upon the right were the 1st Queen’s Surrey, acting as flank-guard, and a Moroccan corps from the Fifth French chapter Army, which had not reached so advanced a position, but was in echelon upon their right rear.

It has already been shown how the 1st Brigade was divided up, the 1st Coldstream being on the right of the 2nd Brigade. The rest of the 1st Brigade had carried out an advance parallel to that described, and many of the Black Watch, who were the right-hand regiment, got mixed with Bulfin’s men when they were driven back to what proved to be the permanent British line. This advance of the 1st Brigade intercepted a strong force of the enemy which was creeping round the left flank of the 2nd Brigade. The counter-stroke brought the flank attack to a standstill. The leading regiments of the 1st Brigade suffered very severely, however, especially the Cameron Highlanders, whose gallantry carried them far to the front. This regiment lost Lieutenant-Colonel MacLachlan, 2 majors, Maitland and Nicholson, 3 captains, 11 lieutenants, and about 300 rank and file in the action. Some of these fell into the hands of the enemy, but the great majority were killed or wounded. The 1st Scots Guards upon the left of the brigade had also heavy casualties, while the Black Watch lost their Colonel, Grant Duff, their Adjutant, Rowan Hamilton, and many men. When the line on their right fell back, they conformed to the movement until they received support from two companies of the 1st Gloucesters from the 3rd Brigade upon their left rear.

The 4th (Guards) Brigade, forming the left of the Second Division, was across the river in battle array by ten o’clock in the morning and moving northwards towards the village of Ostel. Its task was a Supremely difficult one. Dense woods faced it, fringed with the hostile riflemen, while a heavy shell-fire tore through the extended ranks. It Aisne. is safe to say that such an advance could not have been carried out in the heavy-handed German fashion without annihilating losses. As it was, the casualties were heavy, but not sufficient to prevent a continuance of the attack, which at one o’clock carried the farm and trenches which were its objective. The steep slopes and the thick woods made artillery support impossible, though one section of a battery did contrive to keep up with the infantry. The 3rd Coldstream being held up in their advance on the Soupir front, the 1st Irish were moved up on their right flank, but the line could do little more than hold its own. Captain Berners, Lord Guernsey, Lord Arthur Hay, and others were killed at this point. The German infantry advanced several times to counter-attack, but were swept back by the fire of the Guards.

At one period it was found that the general German advance, which had followed the holding of the British attack, was threatening to flow in between the two divisions of the First Army Corps. The 3rd Brigade (Landon’s) was therefore deployed rapidly from the point about a mile south of Vernesse where it had been stationed. Two regiments of the brigade, the 2nd Welsh and the 1st South Wales Borderers, were flung against the heavy German column advancing down the Beaulne ridge and threatening to cut Haig’s corps in two. The Welshmen, worthy successors of their ancestors who left such a name on the battlefields of France, succeeded in heading it off and driving it back so that they were able to extend and get in touch with the right of the Second Division. This consisted of the 5th Brigade (Haking’s) with the 6th (Davies’) upon its left. Both of these brigades had to bear the brunt of continual German counter-attacks, involving considerable losses, both from shell and rifle fire. In spite of this they won their way for a mile or more up the slopes, where they were brought to a standstill and dug themselves into temporary shelter, continuing the irregular diagonal line of trenches which had been started by the brigades upon the right.

It is impossible not to admire the way in which the German general in command observed and attempted to profit by any gap in the British line. It has already been shown how he tried to push his column between the two divisions of the First Corps and was only stopped by the deployment of the 3rd Brigade. Later, an even fairer chance presented itself, and he was quick to take advantage of it. The advance of the Guards Brigade to the Ostel ridge had caused a considerable gap between them and the nearest unit of the Second Corps, and also between the First Corps and the river. A German attack came swarming down upon the weak spot. From Troyon to Ostel, over five miles of ground, Haig’s corps was engaged to the last man and pinned down in their positions. It was not possible to fill the gap. Not to fill it might have meant disaster—disaster under heavy shell-fire with an unfordable river in the rear. Here was a supreme example of the grand work that was done when our cavalry were made efficient as dismounted riflemen. Their mobility brought them quickly to the danger spot. Their training turned them in an instant from horsemen to infantry. The 15th Hussars, the Irish Horse, the whole of Briggs’ 1st Cavalry Brigade, and finally the whole of De Lisle’s 2nd Cavalry Brigade, were thrown into the gap. The German advance was stayed and the danger passed. From now onwards the echelon formed by the units of the First Corps ended with these cavalry brigades near Chavonne to the immediate north of the river.

The Third Division of the Second Corps, being on the immediate left of the operations which have been already described, moved forward upon Aizy, which is on about the same level as Ostel, the objective of the Guards. The 8th (Doran’s) Brigade moved north by a tributary stream which runs down to the Aisne, while the 9th (Shaw’s) tried to advance in line with it on the plateau to the right. Both brigades found it impossible to get any farther, and established themselves in entrenchments about a mile north of Vailly, so as to cover the important bridge at that place, where the 7th Brigade was in reserve. The three Fusilier regiments of the 9th Brigade all lost heavily, and the Lincolns had at one time to recross the river, but recovered their position.

The attack made by the Fifth Division near Missy was held up by a very strong German position among the woods on the Chivres heights which was fronted by wire entanglements. The regiments chiefly engaged were the Norfolks and Bedfords of the 15th Brigade, with the Cornwalls and East Surreys of the 14th Brigade, the remains of the Cheshires being in close support. They crossed the wire and made good progress at first, but were eventually brought to a stand by heavy fire at close range from a trench upon their right front. It was already dusk, so the troops ended by maintaining the position at Missy and Ste. Marguerite, where there were bridges to be guarded.

The Fourth Division of Pulteney’s Third Corps had no better success, and was only able to maintain its ground. It may be remarked, as an example of valiant individual effort, that this division was largely indebted for its ammunition supply to the efforts of Captain Johnston of the Sappers, who, upon a crazy raft of his own construction, aided by Lieutenant Flint, spent twelve hours under fire ferrying over the precious boxes. The familiar tale of stalemate was to be told of the Sixth French Army in the Soissons section of the river. Along the whole Allied line the position was the same, the greatest success and probably the hardest fighting having fallen to the lot of the Eighteenth French Corps, which had taken, lost, and finally retaken Craonne, thus establishing itself upon the lip of that formidable plateau which had been the objective of all the attacks.

In the Vailly region the 5th Cavalry Brigade found itself in a difficult position, for it had crossed the stream as a mounted unit in expectation of a pursuit, and now found itself under heavy fire in the village of Vailly with no possibility of getting forward. The only alternative was to recross the river by the single narrow bridge, which was done at a later date under very heavy fire, the troopers leading their horses over in single file. This difficult operation was superintended by Captain Wright of the Engineers, the same brave officer who had endeavoured to blow up the bridge at Mons. Unhappily, he was mortally wounded on this occasion. On the afternoon of the 14th—it being found that the British artillery was shelling our own advanced trenches—Staff-Captain Harter of the 9th Brigade galloped across the bridge and informed the gunners as to the true position.

Towards evening, in spite of the fact that there were no reserves and that all the troops had endured heavy losses and great fatigue, a general advance was ordered in the hope of gaining the high ground of the Chemin-des-Dames before night. It was nearly sunset when the orders were given, and the troops responded gallantly to the call, though many of them had been in action since daybreak. The fire, however, was very heavy, and no great progress could be made. The First Division gained some ground, but was brought to a standstill. The only brigade which made good headway was Haking’s 5th, which reached the crest of the hill in the neighbourhood of Tilleul-de-Courtecon. General Haking sent out scouts, and finding German outposts upon both his flanks, he withdrew under cover of darkness.

Thus ended the sharp and indecisive action of September 14, the Germans holding their ground, but being in turn unable to drive back the Allies, who maintained their position and opposed an impassable obstacle to the renewed advance upon Paris. The battle was marked by the common features of advance, arrest, and entrenchment, which occurred not only in the British front, but in that of the French armies upon either flank. When the action ceased, the 1st Northamptons and the 1st Queen’s, sent to guard the pressure point at the extreme right of the line, had actually reached the Chemin-des-Dames, the British objective, and had dug themselves in upon the edge of it. From this very advanced spot the British line extended diagonally across the hillside for many miles until it reached the river. Several hundred prisoners and some guns were taken in the course of the fighting. When one considers the predominant position of the Germans, and that their artillery was able to give them constant assistance, whereas that of the British and French was only brought up with the utmost difficulty, we can only marvel that the infantry were able to win and to hold the ground.

The next day, September 15, was spent for the most part in making good the position gained and deepening the trenches to get some protection from the ever-growing artillery fire, which was the more intense as the great siege guns from Maubeuge were upon this day, for the first time, brought into action. At first the terrific explosions of these shells, the largest by far which had ever been brought into an actual line of battle, were exceedingly alarming, but after a time it became realised that, however omnipotent they might be against iron or concrete, they were comparatively harmless in soft soil, where their enormous excavations were soon used as convenient ready-made rifle-pits by the soldiers. This heavy fire led to a deepening of the trenches, which necessitated a general levy of picks and shovels from the country round, for a large portion of such equipment had been lost in the first week of the campaign.

Only two active movements were made in the course of the day, one being that Hamilton’s Third Division advanced once more towards Aizy and established itself a mile or more to the north in a better tactical position. The 7th Brigade suffered considerable casualties in this change, including Colonel Hasted, of the 1st Wilts. The other was that Ferguson’s Fifth Division fell back from Chivres, where it was exposed to a cross fire, and made its lines along the river bank, whence the Germans were never able to drive it, although they were only four Aisne. hundred yards away in a position which was high above it. For the rest, it was a day of navvy’s toil, though the men worked alternately with rifle and with pick, for there were continual German advances which withered away before the volleys which greeted them. By the 16th the position was fairly secure, and on the same day a welcome reinforcement arrived in the shape of the Sixth Division, forming the missing half of Pulteney’s Third Corps.

Its composition is here appended:

| DIVISION VI.—GENERAL KEIR |

16th Infantry Brigade—General Ing. Williams. 1st East Kent. 1st Leicester. 1st Shropshire Light Infantry. 2nd York and Lancaster. 11th Infantry Brigade—General Walter Doran. 1st Royal Fusiliers. 1st N. Stafford. 2nd Leinsters. 3rd Rifle Brigade. 18th Infantry Brigade—General Congreve, V.C. 1st W. York. 1st E. York. 2nd Notts and Derby (Sherwood Foresters). 2nd Durham Light Infantry. Artillery. 2nd Brig. 21, 42, 63. 12th Brig. 43, 86, 87. 24th Brig. 110, 11], 112. 38th Brig. 24, 34, 72. R.G.A. 24. |

This division was kept in reserve upon the south side of the river. The French Commander-in-Chief had intimated that he intended to throw in reinforcements upon the left of the Sixth French Army, and so, as he hoped, to turn the German right. It was determined, therefore, that there should be no attempt at a British advance, but that the Allies should be content with holding the enemy to his positions. The two armies lay facing each other, therefore, at an average distance of about five hundred yards. The pressure was still most severe upon the 2nd Brigade on the extreme right. Bulfin’s orders were to hold on at all costs, as he was the pivot of the whole line. He and his men responded nobly to the responsibility, although both they and their neighbours of Maxse’s 1st Brigade had sustained a loss of over 1000 men each upon the 14th—25 per cent of their number. The shell-fire was incessant and from several converging directions. German infantry attacks were constant by night and by day, and the undrained trenches were deep in water. The men lay without overcoats and drenched to the skin, for the rain was incessant. Yet the sixth day found them on the exact ground upon which they had thrown their weary bodies after their attack. Nations desire from time to time to be reassured as to their own virility. Neither in endurance nor in courage have the British departed from the traditions of their ancestors. The unending strain of the trenches reached the limits of human resistance. But the line was always held.

On September 16 occurred an incident which may be taken as typical of the difference in the spirit with which the British and the Germans make war. Close to the lines of the Guards a barn which contained fifty wounded Germans was ignited by the enemy’s shells. Under a terrific fire a rescue party rushed forward and got the unfortunate men to a place of safety.

Several of the British lost their lives in this exploit, including Dr. Huggan, the Scottish International footballer. The Germans mock at our respect for sport, and yet this is the type of man that sport breeds, and it is the want of them in their own ranks which will stand for ever between us.

September 17 was a day of incessant attacks upon the right of the line, continually repulsed and yet continually renewed. One can well sympathise with the feelings of the German commanders who, looking down from their heights, saw the British line in a most dangerous strategical position, overmatched by their artillery, with a deep river in their rear, and yet were unable to take advantage of it because of their failure to carry the one shallow line of extemporised trenches. Naturally, they came again and again, by night and by day, with admirable perseverance and daring to the attack, but were always forced to admit that nothing can be done against the magazine rifle in hands which know how to use it. They tried here and they tried there, these constant sudden outpourings of cheering, hurrying, grey-clad men. They were natural tactics, but expensive ones, for every new attack left a fresh fringe of stricken men in front of the British lines.

One incident upon the 17th stands out amid the somewhat monotonous record of trench attacks. On the extreme right of the British line a company of the 1st Northamptons occupied a most exposed position on the edge of the Chemin-des-Dames. The men in a German trench which was some hundreds of yards in front hoisted a white flag and then advanced upon the British lines. It is well to be charitable in all these white flag incidents, since it is always possible on either side that unauthorised men may hoist it and the officer in command very properly refuse to recognise it; but in this case the deception appears to have been a deliberate one. These are the facts. On seeing the flag, Captain Savage, of B Company Northamptons, got out of the trench and with Lieutenant Dimmer, of the Rifles, advanced to the Germans. He threw down his sword and revolver to show that he was unarmed. He found a difficulty in getting a direct answer from the Germans, so he saluted their officer, who returned his salute, and turned back to walk to his own trench. Dimmer, looking back, saw the Germans level their rifles, so he threw himself down, crying out, “For God’s sake get down.” Captain Savage stood erect and was riddled with bullets. Many of the Northamptons, including Lieutenant Gordon, were shot down by the same volley. The Germans then attempted an advance, which was stopped by the machine-guns of the 1st Queen’s. Such deplorable actions must always destroy all the amenities of civilised warfare. On the afternoon of the same day, September 17, a more serious attack was made upon the right flank of the advanced British position, the enemy reoccupying a line of trenches from which they had previously been driven. It was a dismal day of wind, rain, and mist, but the latter was not wholly an evil, as it enabled that hard-worked regiment, the 1st Northamptons, under their Colonel, Osborne Smith, to move swiftly forward and, with the help of the 1st Queen’s, carry the place at the bayonet point. Half the Germans in the trench were put out of action, thirty-eight taken, and the rest fled. Pushing on after their success, they found the ridge beyond held by a considerable force of German infantry. The 2nd Rifles had come into the fight, and a dismounted squadron of the composite cavalry regiment put in some good work upon the flank. The action was continued briskly until dark, when both sides retained their ground with the exception of the captured line of trenches, which remained with the British. Seven officers and about 200 men were killed or wounded in this little affair.

The 18th found the enemy still acting upon the Napoleonic advice of Tâtez toujours. All day they were feeling for that weak place which could never be found. The constant attempts were carried on into the night with the same monotonous record of advance leading to repulse. At one time it was the line of the 1st Queen’s—and no line in the Army would be less likely to give results. Then it was the left flank of the First Division, and then the front of the Second. Now and again there were swift counters from the British, in one of which an enemy’s trench was taken by the 1st Gloucesters with the two machine-guns therein. But there was no inducement for any general British advance. “We have nothing to lose by staying here,” said a General, “whereas every day is of importance to the Germans, so the longer we can detain them here the better.” So it seemed from the point of view of the Allies. There is a German point of view also, however, which is worthy of consideration. They were aware, and others were not, that great reserves of men were left in the Fatherland, even as there were in France and in Britain, but that, unlike France and Britain, they actually had the arms and equipment for them, so that a second host could rapidly be called into the field. If these legions were in Belgium, they could ensure the fall of Antwerp, overrun the country, and seize the seaboard. All this could be effected while the Allies were held at the Aisne. Later, with these vast reinforcements, the Aisne. German armies might burst the barrier which held them and make a second descent upon Paris, which was still only fifty miles away. So the Germans may have argued, and the history of the future was to show that there were some grounds for such a calculation. It was in truth a second war in which once again the Germans had the men and material ready, while the Allies had not.

This date, September 18, may be taken as the conclusion of the actual Battle of the Aisne, since from that time the operations defined themselves definitely as a mutual siege and gigantic artillery duel. The casualties of the British at the Aisne amounted, up to that date, to 10,000 officers and men, the great majority of which were suffered by Haig’s First Army Corps. The action had lasted from the 13th, and its outstanding features, so far as our forces were concerned, may be said to have been the remarkable feat of crossing the river and the fine leadership of General Haig in the dangerous position in which he found himself. It has been suggested that the single unbroken bridge by which he crossed may have been a trap purposely laid by the Germans, whose plans miscarried owing to the simultaneous forcing of the river at many other points. As it was, the position of the First Corps was a very difficult one, and a reverse might have become an absolute disaster. It was impossible for General French to avoid this risk, for since the weather precluded all air reconnaissance, it was only by pushing his Army across that he could be sure of the enemy’s dispositions. The net result was one more demonstration upon both sides that the defensive force has so great an advantage under modern conditions that if there be moderate equality of numbers, and if the flanks of each be guarded, a condition of stalemate will invariably ensue, until the campaign is decided by economic causes or by military movements in some other part of the field of operations.

There is ample evidence that for the time the German Army, though able with no great effort to hold the extraordinarily strong position which had been prepared for it, was actually in very bad condition. Large new drafts had been brought out, which had not yet been assimilated by the army. The resistance of Maubeuge had blocked one of their supply railroads, and for some time the commissariat had partially broken down. Above all, they were mentally depressed by meeting such resistance where they had been led to expect an easy victory, by their forced retreat when almost within sight of Paris, and by their losses, which had been enormous. In spite of their own great superiority in heavy guns, the French light field-pieces had controlled the battlefields. There is ample evidence in the letters which have been intercepted, apart from the statements and appearance of the prisoners, to show the want and depression which prevailed. This period, however, may be said to mark the nadir of the German fortunes in this year. The fall of Maubeuge improved their supplies of every sort, their reserves and Landwehr got broken in by the war of the trenches, and the eventual fall of Antwerp and invasion of Western Belgium gave them that moral stimulus which they badly needed.

Some wit amongst the officers has described the war as “months of boredom broken by moments of agony.” It is the duty of the chronicler to record, even if he attempts to alleviate, the former, for the most monotonous procession of events form integral parts of the great whole. The perusal of a great number of diaries and experiences leaves a vague and disconnected recollection behind it of personal escapes, of the terror of high explosives, of the excellence of the rear services of the Army, of futile shellings —with an occasional tragic mishap, where some group of men far from the front were suddenly, by some freak of fate, blown to destruction, — of the discomforts of wet trenches, and the joys of an occasional relief in the villages at the rear. Here and there, however, in the monotony of what had now become a mutual siege, there stand out some episodes or developments of a more vital character, which will be recorded in their sequence.

It may be conjectured that, up to the period of the definite entrenchment of the two armies, the losses of the enemy were not greater than our own. It is in the attack that losses are incurred, and the attack had, for the most part, been with us. The heavier guns of the Germans had also been a factor in their favour. From the 18th onwards, however, the weekly losses of the enemy must have been very much greater than ours, since continually, night and day, they made onslaughts, which attained some partial and temporary success upon the 20th, but which on every other occasion were blown back by the rifle-fire with which they were met. So mechanical and halfhearted did they at last become that they gave the impression that those who made them had no hope of success, and that they were only done at the bidding of some imperious or imperial voice from the distance. In these attacks, though any one of them may have only furnished a few hundred casualties, the total spread over several weeks must have equalled that of a very great battle, and amounted, since no progress was ever made, to a considerable defeat.

Thus on September 19 there was a succession of attacks, made with considerable vivacity and proportional loss. About 4 P.M. one developed in front of the 4th and 6th Brigades of the First Corps, but was speedily stopped. An hour later another one burst forth upon the 7th and 9th Brigades of the Second Corps, with the same result. The artillery fire was very severe all day and the broad valley was arched from dawn to dusk by the flying shell. The weather was still detestable, and a good many were reported ill from the effects of constant wet and cold. The 20th was the date of two separate attacks, one of which involved some hard fighting and considerable loss. The first, at eight in the morning, was upon Shaw’s 9th Brigade and was driven off without great difficulty. The second was the more serious and demands some fuller detail.

On the arrival of the Sixth Division upon the 18th, Sir John French had determined to hold them in reserve and to use them to relieve, in turn, each of the brigades which had been so hard-worked during the previous week. Of these, there was none which needed and deserved a rest more than Bulfin’s 2nd Brigade, which, after their attack upon the Chemin-des-Dames upon the 14th, had made and held the trenches which formed both the extreme right and the advanced point of the British line. For nearly a week these men of iron had lain where the battle had left them. With the object of relieving them, the 18th Brigade (Congreve’s) of the Sixth Division was ordered to take their places. The transfer was successfully effected at night, but the newcomers, who had only arrived two days before from England, found themselves engaged at once in a very serious action. It may have been coincidence, or it may have been that with their remarkable system of espionage the Germans learned that new troops had taken the place of those whose mettle they had tested so often; but however this may be, they made a vigorous advance upon the afternoon of September 20, coming on so rapidly and in such numbers that they drove out the occupants both of the front British trenches—which were manned by three companies of the 1st West Yorkshires—and the adjoining French trench upon the right, which was held by the Turcos. The West Yorkshires were overwhelmed and enfiladed with machine-guns, a number were shot down, and others were taken prisoners.

Fortunately, the rest of the brigade were in immediate support, and orders were given by General Congreve to advance and to regain the ground that had been lost. The rush up the hill was carried out by the 2nd Notts and Derby Regiment (Sherwood Foresters) in the centre, with the remainder of the West Yorks upon their right, and the 2nd Durham Light Infantry upon their left. They were supported by the 1st East Yorks and by the 2nd Sussex, who had just been called out of the line for a rest. The 4th Irish Dragoon Guards at a gallop at at first, and then dismounting with rifle and bayonet, were in the forefront of the fray. The advance was over half a mile of ground, most of which was clear of any sort of cover, but it was magnificently carried out and irresistible in its impetus. All the regiments lost heavily, but all reached their goal. Officers were hit again and again, but staggered on with their men. Captain Popham, of the Sherwood Foresters, is said to have carried six wounds with him up the slope. Fifteen officers and 250 men were shot down, but the lost trench was carried at the point of the bayonet and the whole position re-established. The total casualties were 1364, more than half of which fell upon the West Yorkshires, while the majority of the others were Sherwood Foresters, East Yorkshires, and Durhams. Major Robb, of the latter regiment, was among those who fell. The Germans did not hold the trenches for an hour, and yet the engagement may be counted as a success for them, since our losses were certainly heavier than theirs. There was no gain, however, in ground. The action was more than a mere local attack, and the British line was in danger of being broken had it not been for the determined counterattack of the 18th Brigade and of the Irish dragoons. To the north of this main attack there was another subsidiary movement on the Beaulne ridge, in which the 5th and 6th Brigades were sharply engaged. The 1st King’s, the 2nd H.L.I., and the 2nd Worcesters all sustained some losses.

About this period both the British and the French armies began to strengthen themselves with those heavy guns in which they had been so completely overweighted by their enemy. On the 20th the French in the neighbourhood of our lines received twelve long-range cannon, firing a 35 lb. shell a distance of twelve kilometres. Three days later the opened fire with four new batteries of six-inch howitzers. From this time onwards there was no such great disparity in the heavy artillery, and the wounded from the monster shells of the enemy had at least the slight solace that their fate was not unavenged. The expenditure of shells, however, was still at the rate of ten German to one of the Allies. If the war was not won it was no fault of Krupp and the men of Essen. In two weeks the British lost nearly 3000 men from shell-fire.

It was at this time, September 20, that the Germans Rheims put a climax upon the long series of outrages and vandalisms of which their troops had been guilty by the bombardment of Rheims Cathedral, the Westminster Abbey of France. The act seems to have sprung from deliberate malice, for though it was asserted afterwards that the tower had been used as an artillery observation point, this is in the highest degree improbable, since the summit of the ridge upon the French side is available for such a purpose. The cathedral was occupied at the time by a number of German wounded, who were the sufferers by the barbarity of their fellow-countrymen. The incident will always remain as a permanent record of the value of that Kultur over which we have heard such frantic boasts. The records of the French, Belgian, and British Commissions upon the German atrocities, reinforced by the recollection of the burned University of Louvain and the shattered Cathedral of Rheims, will leave a stain upon the German armies which can never be erased. Their conduct is the more remarkable, since the invasion of 1870 was conducted with a stem but rigid discipline, which won the acknowledgment of the world. In spite of all the material progress and the superficial show of refinement, little more than a generation seems to have separated civilisation from primitive barbarity, which attained such a pitch that no arrangement could be made by which the wounded between the lines could be brought in. Such was the code of a nominally Christian nation in the year 1914.

Up to now the heavier end of the fighting had been borne by Haig’s First Corps, but from the 20th onwards the Second and Third sustained the impact. The action just described, in which the West Yorkshires suffered so severely, was fought mainly by the 18th Brigade of Pulteney’s Third Corps. On the 21st it was the turn of the Second Corps. During the night the 1st Wiltshire battalion of McCracken’s 7th Brigade was attacked, and making a strong counter-attack in the morning they cleared a wood with the bayonet, and advanced the British line at that point. A subsequent attack upon the same brigade was repulsed. How heavy the losses had been in the wear and tear of six days’ continual trench work is shown by the fact that when on this date the 9th Brigade (Shaw’s) was taken back for a rest it had lost 30 officers and 860 men since crossing the Aisne.

The German heavy guns upon the 21st set fire to the village of Missy, but failed to dislodge the 1st East Surreys who held it. This battalion, in common with the rest of Ferguson’s Division, were dominated night and day by a plunging fire from above. It is worth recording that in spite of the strain, the hardship, and the wet trenches, the percentage of serious sickness among the troops was lower than the normal rate of a garrison town. A few cases of enteric appeared about this time, of which six were in one company of the Coldstream Guards. It is instructive to note that in each case the man belonged to the uninoculated minority.

A plague of spies infested the British and French lines at this period, and their elaborate telephone installations, leading from haystacks or from cellars, showed the foresight of the enemy. Some of these were German officers, who bravely took their Lives in their hands from the patriotic motive of helping their country. Others, alas, were residents who had sold their souls for German gold. One such—a farmer—was found with a telephone within his house and no less a sum than a thousand pounds in specie. Many a battery concealed in a hollow, and many a convoy in a hidden road, were amazed by the accuracy of a fire which was really directed, not from the distant guns, but from some wayside hiding place. Fifteen of these men were shot and the trouble abated.

The attacks upon the British trenches, which had died down for several days, were renewed with considerable vigour upon September 26. The first, directed against the 1st Queen’s, was carried out by a force of about 1000 men, who advanced in close order, and, coming under machine-gun fire, were rapidly broken up. The second was made by a German battalion debouching from the woods in front of the 1st South Wales Borderers. This attack penetrated the line at one point, the left company of the regiment suffering severely, with all its officers down. The reserve company, with the help of the 2nd Welsh Regiment, retook the trenches after a hot fight, which ended by the wood being cleared. The Germans lost heavily in this struggle, 80 of them being picked up on the very edge of the trench. The Borderers also had numerous casualties, which totalled up to 7 officers and 182 men, half of whom were actually killed.

The Army was now in a very strong position, for the trenches were so well constructed that unless a shell by some miracle went right in, no harm would result. The weather had become fine once more, and the flying service relieved the anxieties of the commanders as to a massed attack. The heavy artillery of the Allies was also improving from day to day, especially the heavy British howitzers, aided by aeroplane observers with a wireless installation. On the other hand, the guns were frequently hit by the enemy’s fire. The 22nd R.F.A. lost a gun, the 50th three guns, and other batteries had similar losses. Concealment had not yet been reduced to a science.

At this period the enemy seems to have realised that his attacks, whether against the British line or against the French armies which flanked it, and had fought throughout with equal tenacity, were a mere waste of life. The assaults died away or became mere demonstrations. Early in October the total losses of the Army upon the Aisne had been 561 officers and 12,980 men, a proportion which speaks well for the coolness and accuracy of the enemy’s sharp-shooters, while it exhibits our own forgetfulness of the lessons of the African War, where we learned that the officer should be clad and armed so like the men as to be indistinguishable even at short ranges. Of this large total the Second Corps lost 136 officers and 3095 men, and the First Corps 348 officers and 6073 men, the remaining 77 officers and 3812 men being from the Third Corps and the cavalry.

It was at this period that a great change came over both the object and the locality of the operations. This change depended upon two events which had occurred far to the north, and reacted upon the great armies locked in the long grapple of the Aisne. The first of these controlling circumstances was that, by the movement of the old troops and the addition of new ones, each army had sought to turn the flank of the other in the north, until the whole centre of gravity of the war was transferred to that region. A new French army under General Castelnau, whose fine defence of Nancy had put him in the front of French leaders, had appeared on the extreme left wing of the Allies, only to be countered by fresh bodies of Germans, until the ever-extending line lengthened out to the manufacturing districts of Lens and Lille, where amid pit-shafts and slag-heaps the cavalry of the French and the Germans tried desperately to get round each other’s flank. The other factor was the fall of Antwerp, which had released very large bodies of Germans, who were flooding over Western Belgium, and, with the help of great new levies from Germany, carrying the war to the sand-dunes of the coast. The operations which brought about this great change open up a new chapter in the history of the war. The actual events which culminated in the fall of Antwerp may be very briefly handled, since, important as they were, they were not primarily part of the British task, and hence hardly come within the scope of this narrative.

The Belgians, after the evacuation of Brussels in August, had withdrawn their army into the widespread fortress of Antwerp, from which they made frequent sallies upon the Germans who were garrisoning their country. Great activity was shown and several small successes were gained, which had the useful effect of detaining two corps which might have been employed upon the Aisne. Eventually, towards the end of September, the Germans turned their attention seriously to the reduction of the city, with a well founded confidence that no modern forts could resist the impact of their enormous artillery. They drove the garrison within the lines, and early in October opened a bombardment upon the outer forts with such results that it was evidently only a matter of days before they would fall and the fine old city be faced with the alternative of surrender or destruction. The Spanish fury of Parma’s pikemen would be a small thing compared to the furor Teutonicus working its evil deliberate will upon town-hall or cathedral, with the aid of fire-disc, petrol-spray, or other products of culture. The main problem before the Allies, if the town could not be saved, was to ensure that the Belgian army should be extricated and that nothing of military value which could be destroyed should be left to the invaders. No troops were available for a rescue, for the French and British old formations were already engaged, while the new ones were not yet ready for action. In these circumstances, a resolution was come to by the British leaders which was bold to the verge of rashness and so chivalrous as to be almost quixotic. It was determined to send out at the shortest notice a naval division, one brigade of which consisted of marines, troops who are second to none in the country’s service, while the other two brigades were young amateur sailor volunteers, most of whom had only chapter been under arms for a few weeks. It was an extraordinary experiment, as testing how far the average sport-loving, healthy-minded young Briton needs only his equipment to turn him into a soldier who, in spite of all rawness and inefficiency, can still affect the course of a campaign. This strange force, one-third veterans and two-thirds practically civilians, was hurried across to do what it could for the failing town, and to demonstrate to Belgium how real was the sympathy which prompted us to send all that we had. A reinforcement of a very different quality was dispatched a few days later in the shape of the Seventh Division of the Regular Army, with the Third Division of Cavalry. These fine troops were too late, however, to save the city, and soon found themselves in a position where it needed all their hardihood to save themselves.

The Marine Brigade of the Naval Division under General Paris was dispatched from England in the early morning and reached Antwerp during the night of October 3. They were about 2000 in number. Early next morning they were out in the trenches, relieving some weary Belgians. The Germans were already within the outer enceinte and drawing close to the inner. For forty-eight hours they held the line in the face of heavy shelling. The cover was good and the losses were not heavy. At the end of that time the Belgian troops, who had been a good deal worn by their heroic exertions, were unable to sustain the German pressure, and evacuated the trenches on the flank of the British line. The brigade then fell back to a reserve position in front of the town.

On the night of the 5th the two other brigades of the division, numbering some 5000 amateur sailors, arrived in Antwerp, and the whole force assembled on the new line of defence. Mr. Winston Churchill showed his gallantry as a man, and his indiscretion as a high official, whose life was of great value to his country by accompanying the force from England. The bombardment was now very heavy, and the town was on fire in several places. The equipment of the British left much to be desired, and their trenches were as indifferent as their training. None the less they played the man and lived up to the traditions of that great service upon whose threshold they stood. For three days these men, who a few weeks before had been anything from schoolmasters to tram-conductors, held their perilous post. They were very raw, but they possessed a great asset in their officers, who were usually men of long service. But neither the lads of the naval brigades nor the war-worn and much-enduring Belgians could stop the mouths of those inexorable guns. On the 8th it was clear that the forts could no longer be held. The British task had been to maintain the trenches which connected the forts with each other, but if the forts went it was clear that the trenches must be outflanked and untenable. The situation, therefore, was hopeless, and all that remained was to save the garrison and leave as little as possible for the victors. Some thirty or forty German merchant ships in the harbour were sunk and the great petrol tanks were set on fire. By the light of the flames the Belgian and British forces made their way successfully out of the town, and the good service rendered later by our Allies upon the Yser and elsewhere is the best justification of the policy which made us strain every nerve in order to do everything which could have a moral or material effect upon them in their darkest hour. Had the British been able to get away unscathed, the whole operation might have been reviewed with equanimity if not with satisfaction, but, unhappily, a grave misfortune, arising rather from bad luck than from the opposition of the enemy, came upon the retreating brigades, so that very many of our young sailors after their one week of crowded life came to the end of their active service for the war.

On leaving Antwerp it had been necessary to strike to the north in order to avoid a large detachment of the enemy who were said to be upon the line of the retreat. The boundary between Holland and Belgium is at this point very intricate, with no clear line of demarcation, and a long column of British somnambulists, staggering along in the dark after so many days in which they had for the most part never enjoyed two consecutive hours of sleep, wandered over the fatal line and found themselves in firm but kindly Dutch custody for the rest of the war. Some fell into the hands of the enemy, but the great majority were interned. These men belonged chiefly to three battalions of the 1st Brigade. The 2nd Brigade, with one battalion of the 1st, and the greater part of the Marines, made their way to the trains at St. Gilles-Waes, and were able to reach Ostend in safety. The remaining battalion of Marines, with a number of stragglers of the other brigades, were cut off at Morbede by the Germans, and about half of them were taken, while the rest fought their way through in the darkness and joined their comrades. The total losses of the British in the whole misadventure from first to last were about 2500 men —a high price, and yet not too high when weighed against the results of their presence at Antwerp. On October 10 the Germans under General Von Beseler occupied the city. Mr. Powell, who was present, testifies that 60,000 marched into the town, and that they were all troops of the active army.

It has already been described how the northern ends of the two contending armies were endeavouring to outflank each other, and there seemed every possibility that this process would be carried out until each arrived at the coast. Early in October Sir John French represented to General Joffre that it would be well that the British Army should be withdrawn from the Aisne and take its position to the left of the French forces, a move which would shorten its line of communications very materially, and at the same time give it the task of defending the Channel coast. General Joffre agreed to the proposition, and the necessary steps were at once taken to put it into force. The Belgians had in the meanwhile made their way behind the line of the Yser, where a formidable position had been prepared. There, with hardly a day of rest, they were ready to renew the struggle with the ferocious ravagers of their country. The Belgian Government had been moved to France, and their splendid King, who will live in history as the most heroic and chivalrous figure of the war, continued by his brave words and noble example to animate the spirits of his countrymen.

From this time Germany was in temporary occupation of all Belgium, save only the one little corner, the defence of which will be recorded for ever. Little did she profit by her crime or by the excuses and forged documents by which she attempted to justify her action. She entered the land in dishonour and dishonoured will quit it. William, Germany, and Belgium are an association of words which will raise in the minds of posterity all that Parma, Spain, and the Lowlands have meant to us—an episode of oppression, cruelty, and rapacity, which fresh generations may atone for but can never efface.

1. Until an accurate German military history of the war shall appear, it is difficult to compute the exact rival forces in any engagement, but in this attack of the 2nd Brigade, where six British regiments may be said to have been involved, there are some data. A German officer, describing the same engagement, says that, apart from the original German force, the reinforcements amounted to fourteen battalions, from the Guards’ Jaeger, the 4th Jaeger Battalion, 65th, 13th Reserve, and 13th and 16th Landwehr Regiments.