VII. The Battle of Loos

The First Day—September 25

General order of battle—Check of the Second Division — Advance of the Ninth and Seventh Divisions—Advance of the First Division—Fine progress of the Fifteenth Division—Capture of Loos—Work of the Forty-seventh London Division

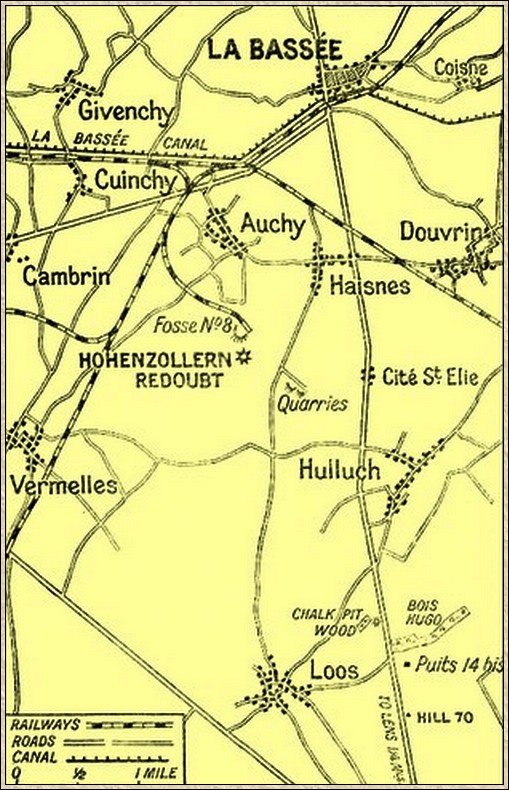

Whilst the Army had lain in apparent torpidity during the summer a torpidity which was only broken by the sharp engagements at Hooge and elsewhere great preparations for a considerable attack had been going forward. For several months the sappers and the gunners had been busy concentrating their energies for a serious effort which should, as it was hoped, give the infantry a fair chance of breaking the German line. Similar preparations were going on among the French, both in Foch’s Tenth Army to the immediate right of the British line, and also on a larger scale in the region of Champagne. Confining our attention to the British effort, we shall now examine the successive stages of the great action in front of Hulluch and Loos the greatest battle, both as to the numbers engaged and as to the losses incurred, which had ever up to that date been fought by our Army.

Loos District

The four days which preceded the great attack of September 25 were days of great activity. An incessant and severe bombardment was directed upon the German lines along the whole front, but especially in the sector to the immediate south of the La Bassée Canal, where the main thrust was to be made. To this severe fire the Germans made hardly any reply, though whether from settled policy or from a comparative lack of munitions is not clear. On each of the days a feint attack was made upon the German line so far as could be done without actually exposing the men. The troops for the assault were gradually brought into position, and the gas-cylinders, which were to be used for the first time, were sunk in the front parapets.

The assault in the main area was to extend from the La Bassée Canal in the north to the village of Grenay in the south, a front of about seven miles, and it was to be supported and supplemented by many subsidiary attacks along the whole line up to the Ypres salient, and northwards still to where the monitors upon the coast held the German coastguards to their sand-dunes. For the moment we will deal only with the fortunes of the main attack. This was to be delivered by two army corps, both belonging to Haig’s First Army, that tempered blade which has so often been the spear-head for the British thrust. The corps were the First (Hubert Gough’s) and the Fourth (Rawlinson’s). It will be remembered that a British army corps now consisted of three divisions, so that the storming line was composed of six divisions, or about seventy thousand infantry.

The line of the advance was bisected by a high road from Vermelles to Hulluch. This was made the boundary line between the two attacking corps. To the left, or north of this road, was the ground of the First Corps; to the right, or south, of the Fourth.

The qualities of the Regular and Territorial regiments had already been well attested. This was the first occasion, however, when, upon a large scale, use was made of those new forces which now formed so considerable a proportion of the whole. Let it be said at once that they bore the test magnificently, and that they proved themselves to be worthy of their comrades to the right and the left. It had always been expected that the new infantry would be good, for they had in most cases been under intense training for a year, but it was a surprise to many British soldiers, and a blow to the prophets in Berlin, to find that the scientific branches, the gunners and the sappers, had also reached a high level. “Our enemy may have hoped,” said Sir John French, “not perhaps without reason, that it would be impossible for us, starting with such small beginnings, to build up an efficient artillery to provide for the very large expansion of the Army. If he entertained such hopes he has now good reason to know that they have not been justified by the result. The efficiency of the artillery of the new armies has exceeded all expectations.” These were the guns which, in common with many others of every calibre, worked furiously in the early dawn of Saturday, September 25, to prepare for the impending advance. The high explosives were known to have largely broken down the German system of defences, but it was also known that there were areas where the damage had not been great and where the wire entanglements were still intact. No further delay could be admitted, however, if our advance was to be on the same day as that of the French. The infantry, chafing with impatience, were swarming in the fire trenches. At 5.40 A.M. the gas-cylinders were turned on. At 6:30 A.M. the guns ceased fire, and the ardent soldiers Regulars, New, and Territorials dashed forward upon their desperate venture.

The following rough diagram of the action will help the reader to understand the order in which the six divisions attacked, and in a very rough way the objectives in front of them. It is impossible to describe simultaneously the progress of so extended a line.

Battle of Loos

It will be best, therefore, to take the various divisions from the northern end, and to follow the fortunes of each until it reached some definite limit. Afterwards an attempt will be made to co-ordinate these results and show their effects upon each other.

The second regular division (Home), acting upon the extreme left of the main attack, had two brigades north of the La Bassée Canal and one to the south. The most northern was the 5th (Cochrane’s), and its operations really formed part of the subsidiary attacks, and will be treated under that head. South of it was the 6th (Daly’s), to the immediate north of the canal. The gas, drifting slowly up the line before a slight southern breeze, had contaminated the air in this quarter, and many of the men were suffering from the effects. None the less, at half-past six the advance was made in a most dashing manner, but the barbed wire defences were found to be only partially damaged and the trenches to be intact, so no progress could be made. The 2nd South Staffords and 1st King’s Liverpools on the left and right reached the German position, but in face of a murderous fire were unable to make good their hold, and were enduring heavy losses, shared in a lesser degree by the 1st Rifles and 1st Berks in support. Upon their right, south of the canal, was the 19th Brigade (Robertson). The two leading regiments, the 1st Middlesex and 2nd Argylls, sprang from the trenches and rushed across the intervening space, only to find themselves faced by unbroken and impassable wire. For some reason, probably the slope of the ground, the artillery had produced an imperfect effect upon the defences of the enemy in the whole sector attacked by the Second Division, and if there is one axiom more clearly established than another during this war, it is that no human heroism can carry troops through uncut wire. They will most surely be shot down faster than they can cut the strands. The two battalions lay all day, from morning till dusk, in front of this impenetrable obstacle, lashed and scourged by every sort of fire, and losing heavily. Two companies of the 2nd Welsh Fusiliers, who gallantly charged forward to support them, shared their tragic experience. It was only under the cover of dusk that the survivors were able to get back, having done nothing save all that men could do. Their difficult situation was rendered more desperate by the fact that the wind drifted the gas that filthy and treacherous ally over a portion of the line, and some of our soldiers were poisoned by the effects. The hold-up was the more unfortunate, as it left the Germans the power to outflank the whole advance, and many of the future difficulties arose from the fact that the enemy’s guns were still working from Auchy and other points on the left rear of the advancing troops. In justice to the Second Division, it must be remembered that they were faced by the notoriously strong position called “the railway triangle,” and also that it is on the flanking units The that the strain must especially fall, as was shown equally clearly upon the same day in the great French advance in Champagne.

The advance of the next division, the Ninth Scottish Division (Thesiger’s) of the new armies, was of a most energetic nature, and met with varying fortunes according to the obstacles in their path. The valour and perseverance of the men were equally high in each of its brigades. By an unfortunate chance, General Landon, the officer who had played so essential a part on the fateful October 31, 1914, and who had commanded the Ninth Division, was invalided home only two days before the battle. His place was taken by General Thesiger, who had little time in which to get acquainted with his staff and surroundings. The front to be assaulted was of a most formidable nature. This Hohenzollern Redoubt jutted forward from the main German line, and was an enclosure seamed with trenches, girdled with wire, and fringed with machine- guns. Behind and to the north of it lay the slag-heap Fosse 8. The one favourable point lay in the fact that the attacking infantry had only a hundred yards to cross, while in the other parts of the line the average distance was about a quarter of a mile.

The attack of the Ninth Division was carried out with two brigades, the 26th (Ritchie) and 28th (Dickens), with the 27th (Bruce) in close support.

Continuing the plan of taking each unit from the north, we will follow the tragic fortunes of the 28th Brigade on the left. This brigade seems to have been faced by the same unbroken obstacles which had held up their neighbours of the Second Division upon the left, and they found it equally impossible to get forward, though the attack was urged with all the constancy of which human nature is capable, as the casualty returns only too clearly show.

The most veteran troops could not have endured a more terrible ordeal or preserved a higher heart than these young soldiers in their first battle. The leading regiments were the 6th Scottish Borderers and the 11th Highland Light Infantry. Nineteen officers led the Borderers over the parapet. Within a few minutes the whole nineteen, including Colonel Maclean and Major Hosley, lay dead or wounded upon the ground. Valour could no further go. Of the rank and file of the Borderers some 500 out of 1000 were lying in the long grass which faced the German trenches. The Highland Light Infantry had suffered very little less. Ten officers and 300 men fell in the first rush before they were checked by the barbed wire of the enemy. Every accumulation of evil which can appal the stoutest heart was heaped upon this brigade not only the two leading battalions, but their comrades of the 9th Seaforths and 10th H.L.I, who supported them. The gas hung thickly about the trenches, and all of the troops, but especially the 10th H.L.I., suffered from it. Colonel Graham of this regiment was found later incoherent and half unconscious from poisoning, while Major Graham and four lieutenants were incapacitated in the same way. The chief cause of the slaughter, however, was the uncut wire, which held up the brigade while the German rifle and machine-gun fire shot them down in heaps. It was observed that in this part of the line the gas had so small an effect upon the enemy that their infantry could be seen with their heads and shoulders clustering thickly over their parapets as they fired down at the desperate men who tugged and raved in front of the wire entanglement. An additional horror was found in the shape of a covered trench, invisible until one fell into it, the bottom of which was studded with stakes and laced with wire. Many of the Scottish Borderers lost their lives in this murderous ditch. In addition to all this, the fact that the Second Division was held up exposed the 28th Brigade to fire on the flank. In spite of every impediment, some of the soldiers fought their way onwards and sprang down into the German trenches; notably Major Sparling of the Borderers and Lieutenant Sebold of the H.L.I, with a handful of men broke through all opposition. There was no support behind them, however, and after a time the few survivors were compelled to fall back to the trenches from which they had started, both the officers named having been killed. The repulse on the left of the Ninth Division was complete. The mangled remains of the 28th Brigade, flushed and furious but impotent, gathered together to hold their line against a possible counter-attack. Shortly after mid-day they made a second attempt at a forward movement, but 50 per cent of their number were down, all the battalions had lost many of their officers, and for the moment it was not possible to sustain the offensive.

A very different fate had befallen the 26th Brigade upon their right. The leading battalions of this brigade were the 5th Camerons on the left, gallantly led by Lochiel himself, the hereditary chieftain of the clan, and the 7th Seaforths on the right. These two battalions came away with a magnificent rush, closely followed by the 8th Gordons and the 8th Black Watch. It was a splendid example of that furor Scoticus which has shown again and again that it is not less formidable than the Teutonic wrath. The battalions were over the parapet, across the open, through the broken wire, and over the entrenchment like a line of Olympic hurdlers. Into the trenches they dashed, seized or killed the occupants, pressed rapidly onwards up the communications, and by seven o’clock had made their way as far as Fosse 8, a coal-mine with a long, low slagheap lying in the rear of the great work, but linked up to it in one system of defences. It was a splendid advance, depending for its success upon the extreme speed and decision of the movement. Many officers and men, including Lord Sempill, the gallant Colonel of the Black Watch, were left upon the ground, but the front of the brigade rolled ever forwards. Not content with this considerable success, one battalion, the 8th Gordons, with a handful of the Black Watch, preserved sufficient momentum to carry it on to the edge of the fortified village of Haisnes, in the rear of the German position. The reserve brigade, the 27th, consisting of the 11th and 12th Royal Scots, 10th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, and 6th Scots Fusiliers, swept onwards in support of this movement. This brigade had varying fortunes, part of it being held up by wire. It did not get so far forward as the brigade upon its left, but it reached and took Fosse Alley, to the immediate west of the Lens-Hulluch road. This position it held against bombing attacks upon each flank until the morning of Monday the 27th, as will be described later. The Highlanders upon their left, who had got nearly to Haisnes, dropped back when they found themselves unsupported, and joined the rest of their brigade in the neighbourhood of Fosse 8.

It should be mentioned that the field-guns of the 52nd Brigade E.F.A. pushed up in the immediate rear of the firing line of the Ninth Division, and gave effective support to the infantry. The fact that they could do this across the open tends to show that infantry supports could be pushed up without being confined unduly to the communication trenches. The spirited action of these guns was greatly appreciated by the infantry.

For the moment we will leave the Ninth Division, its left held up in line with the Second Division, its right flung forward through the Hohenzollern Redoubt and Fosse 8 until the spray from the wave had reached as far as Haisnes. Let us turn now to the veterans of the Seventh Division, the inheritors of the glories of Ypres, who filled the space between the right of the Ninth Division and the road from Vermelles to Hulluch which divided Gough’s First and Rawlinson’s Fourth Corps. This division was constituted as before, save that the 8th and 9th Devons of the New Army had taken the place of the two Guards battalions in the 20th Brigade. Upon receiving the word to advance, “Over the top and the best of luck!” the men swarmed on short ladders out of the fire trenches and advanced with cool, disciplined valour over the open ground. On reaching the German wire the leading brigades the 22nd on the left with the 2nd Warwicks and 1st South Staffords in the lead, the 20th on the right with the 2nd Gordons and 8th Devons in the place of honour lay down for a short breather, while each soldier obeyed instructions by judging for himself the point at which the broken, tangled mass of writhing strands could most easily be penetrated. Then once more the whistles blew, the men rushed forward, and, clearing the wire, they threw themselves into the front trench. The garrison of 200 men threw their arms down and their hands up with the usual piteous but insincere cry of “Kameraden!” Flooding over the line of trenches, the division pushed rapidly on without a check until they reached the Quarries, a well-marked post in front of the village of Hulluch. Here more prisoners and eight field-guns were taken by the 20th Brigade. From the Quarries to the village is roughly half a mile of uphill ground, devoid of cover. The impetus of the advance carried the men on until they were at the very edge of the village, where they were held up by the furious fire and by a line of barbed wire, which was bravely cut by Private Vickers of the 2nd Warwicks and other devoted men. Another smaller village, Cité St. Élie, to the north of Hulluch, was also reached, the 2nd Queen’s Surrey making good the western edge of it. At both these points the division had reached its limit, but still farther to the north its left-hand brigade was at the southern outskirts of Haisnes in touch with-the gallant men of the Ninth Division, who were to the west of that important village. These advanced lines could not be held without supports; the 21st Brigade had already been absorbed farther back, and the men of the Seventh Division fell back about 4 P.M. as far as the Quarries, where for a time they remained, having lost many officers and men, including Colonel Stansfeld of the 2nd Gordons, a gallant officer who was hit by a shell in the first advance, but asked only that he should be let lie where he could see his men. Colonel Heath of the Surreys was also killed after the return to the Quarries.

Such was the advance of the First Army Corps, ending in a bloody repulse upon the left of the line and a hardly less bloody success upon the right. Across the Vermelles-Hulluch high road, the Fourth Army Corps had been advancing on the same line, and its fortunes had been very similar to those of its neighbour. The First Division was operating on the left of the corps, with the Fifteenth Scottish Division (New) in the centre and the Forty-seventh Territorial (London) on the right. Thus the First Division was advancing upon Hulluch on the immediate right of the Seventh Division, so that its operations are the next to be considered.

The attack of this division was carried out by the 1st Brigade upon the left and by the 2nd upon the right, while the 3rd was in support. Two battalions, the 9th King’s Liverpool and the London Scottish, acted as a small independent unit apart from the brigades. The respective objectives for the two leading brigades were the Chalk Pit and Fosse 14 for the 2nd, while the 1st was to aim at Hulluch. These objectives were somewhat diverging, and the two Territorial battalions, forming what was called Green’s Force, were to fill up the gap so occasioned, and to prevent any German counter-attack coming through.

Both brigades soon found great difficulties in their path. In the case of each the wire was but imperfectly cut, and the German trenches were still strong.

We will first follow the fortunes of the 1st Brigade. Their rush was headed by two brave battalions of the New Army, the 8th Berkshires on the left and the 10th Gloucesters on the right. Both of these units did extraordinarily well, and after bearing down a succession of obstacles got as far as the edge of Hulluch, capturing three lines of trenches and several guns upon the way. The 1st Camerons pressed close at their heels, lending them the weight to carry them over each successive difficulty. The advance took some time and was very costly. The Berkshires alone in the course of the day lost 17 officers and 400 men, and were led by a young sub-lieutenant (Lawrence) at the close. The Gloucesters and Camerons suffered almost as heavily.

The experience of the 2nd Brigade to the immediate south was still more trying, and it was held up to an extent which had a serious bearing upon the fortunes of the day. The German trenches near Lone Tree, which faced the brigade, were found to be intact and strongly covered by wire. They were attacked by the 2nd Rifles and 1st North Lancashires, with the 2nd Sussex in immediate support, but no progress could be made. The 1st Northamptons threw themselves into the fight, but still the trench was held at a time when it was vital that the 2nd Brigade should be at its post in the general scheme of advance. The ground was taken, however, on each flank of the Lone Tree position, and Green’s Force, whose function had been to link up the diverging operations of the two brigades, was brought up for the attack. The two battalions advanced over six hundred yards by platoon rushes under heavy gusts of fire. As they reached a point within fifty yards of the German line, a few grey-clad, battle-stained infantrymen clambered slowly on to the parapet with outstretched hands. Upon the British ceasing their fire a party of 3 officers and 400 men were marched out of the trenches and gave themselves up. Their stout resistance is a lesson in the effect which a single obstinate detachment can exert in throwing a large scheme out of gear.

The 1st Brigade had now got through upon the left, and the 2nd was able to follow them, so that the whole force advanced as far as the Lens-Hulluch road, getting in touch with the 20th Brigade of the Seventh Division on the left. Here the resistance was strong and the fire heavy. The division had lost very heavily. Of the 9th King’s Liverpool only Colonel Ramsay, 4 subalterns, and 120 men were left, while many of the other battalions were almost as hard hit. It was now raining and the light was failing. The men dug themselves in near the old German trenches, the 3rd Brigade coming up and taking its position on the right flank, where late that night it connected up by means of its outer unit, the 2nd Welsh, with the Twenty-fourth Division, which had come up in support.

The temporary check to the advance of the First Division had exposed the left flank of its neighbour to the south, the Fifteenth (M’Cracken’s) Scottish Division of the New Army. The two divisions were to have met at Fosse 14, but the Fifteenth Division arrived there some hours before the others, for the reason already stated. In spite of this a very fine advance was made, which gained a considerable stretch of ground and pierced more deeply than any other into the German line. The 46th Brigade was on the left, consisting of the 7th Scots Borderers and 12th Highland Light Infantry in front, with the 8th Borderers and 10th Scottish Rifles behind them. It was upon the parapet in front of this brigade that Piper Laidlaw marched up and down before the attack under a heavy fire, warming the blood of the crouching men with the maddening scream of his war-pipes. Not until he was shot down did this gallant man cease to urge forward his comrades. The 46th Brigade dashed forward at the signal, and with a fine fury flooded over the German trenches, which they carried at a rush, storming onwards across the Lens road and up the long slope of Hill 70, taking Fosse 14 upon the way, and eventually reaching the summit of the incline. The 45th supporting Brigade came along after them, detaching, as they passed, 100 bombers of the 6th Camerons to help the First Division to get forward. These brave Highlanders held the advanced line for some hours under heavy fire from the Lens batteries.

The 44th Brigade upon the right of the 46th had made an advance which was equally fiery and successful. In this brigade the 9th Black Watch and 8th Seaforths were in the lead, with the 7th Camerons and 10th Gordons behind. This brigade dashed into the main street of Loos, where they met the Londoners of Barter’s Forty-seventh Division. They helped to consolidate this flank and to clear the houses of Loos, while some of them pushed forward towards Hill 70. When they reached the crest of the hill they found the remains of the 46th Brigade, consisting of remnants of the 12th H.L.I., 7th Scots Borderers, and 10th Scottish Rifles, upon their left. It is possible that they could have dug in and held their own, but the objective as given in the original orders had been the village of St. Augustine, and with heroic perseverance these brave men would be contented with nothing less than the full performance or death in the attempt. Alas! for many of them it was the latter. Gathering themselves together, they flung themselves forward over the crest. On the other side was a long, low slope with isolated houses at the bottom, the suburbs of the village of St. Laurent, which they mistook for St. Augustine. These crackled at every window with machine-gun fire. Of the devoted band who rushed forward none reached the houses. The few survivors fell back upon the crest, and then, falling back about one hundred and fifty yards, they dug in upon the slope on the west side of it. Their position was an extraordinarily dangerous one, for they had no protection upon the left flank, where lay a thick wood the Bois Hugo through which a German attack might come which would cut them off from the Army. Colonel Purvis, of the Highland Light Infantry, with quick foresight, built up a thin line of resistance upon this side from Fosse 14 in the south to the advanced left point, manning it with a few of his own men under Lieutenant M’Neil. A welcome reinforcement of the 6th Camerons and 7th Scots Fusiliers from the 45th Brigade were thrown in to strengthen this weak point. This was done about 1 P.M. It was only just in time, for in the afternoon the German infantry did begin to debouch from the wood, but finding organised resistance they dropped back, and their advance on this line was not renewed until the next morning, when it fell upon the Twenty-first Division. For a time the pressure was very great, but the men rallied splendidly round a tattered flag bearing the Cameron tartan, and, though it was impossible to get forward, they still, in a mixed and straggling line with hardly any officers, held firmly to their ground. Late in the evening the 13th Royal Scots and the 11th Argyll and Sutherlands came up to thicken the line.

Leaving the Fifteenth Division holding on desperately to that advanced position where, as Captain Beith has tersely said, a fringe of Jocks and Sandies lie to mark the farthest point of advance, we turn to the remaining division upon the right the Forty-seventh London, under General Barter. This division upheld splendidly upon this bloody day the secular reputation of the Cockney as a soldier. With a keen, quick brain, as well as a game heart, the Londoner, like the Parisian, has proved that the artificial life of a great city does not necessarily dull the primitive qualities which make the warrior. The cream of the London Territorial regiments had already been distributed among regular brigades, and had made themselves an individual name, but this was the first occasion upon which a whole division was engaged in a really serious operation.

The left of the division was formed by Thwaites’ 141st Brigade with the 18th London Irish in the front line and the 20th Blackheath Battalion in immediate support. To their right was Cuthbert’s 140th Brigade, which formed the extreme right of the whole attack, a position which caused them to think as much of their flank protection as of their frontal advance. This brigade had the 6th and 7th Londons in the van, with the 8th and 15th (Civil Service) in support. The 142nd Brigade (Willoughby) was in the second line.

The advance of the 141st Brigade was a splendid one. At the whistle the 18th London Irish, with a fighting yell, flooded over the parapet with their regimental football kicked in front of them, and were into the German trench like a thunderbolt. A few minutes later they were followed by the Blackheath men, who passed the captured trench, rushed on to the second, and finally won the third, which opened for them the road to Loos. Into the south end of Loos they streamed, while the 44th Brigade of the Fifteenth Division rushed the north end, turning out or capturing the 23rd Silesians, who held the post. The 19th St. Pancras Battalion followed up the attack, while the 17th (Poplar) were in reserve. Meanwhile, the 140th Brigade had done most useful work by making a lodgment on the Double Grassier, formidable twin slag-heaps which had become a German fort. The ground to the immediate south of Loos was rapidly seized and consolidated by the Londoners, several guns being captured in the chalk pits near the village. This operation was of permanent importance, as the successful British advance would inevitably form a salient projecting into the hostile lines, which would be vulnerable if there were not some good defensive position on the flank. The work of the Forty-seventh Division assured such a line in the south.

By mid-day, as has been shown, the British advance had spent its momentum, and had been brought to a standstill at all points. The German lines had been almost but not quite shattered. A map of the photographed trenches shows that beyond the point reached by the advanced troops there was only the last line which held them up. To the east of that was open country. But the German reserves were hurrying up from all quarters in their rear, from Roulers, from Thielt, from Courtrai and Menin and Douai. At the latter place was a division of Guards just brought across from the Russian front. These also were hurried into the fight. The extreme British line was too thin for defence, and was held by exhausted men. They were shelled and bombed and worn down by attack after attack until they were compelled to draw slowly back and re-form on interior lines. The grand salient which had been captured with such heroic dash and profuse loss of life was pared down here and contracted there. The portion to the south held by the Londoners was firmly consolidated, including the important village of Loos and its environs. An enormous mine crane, three hundred feet high, of latticed iron, which had formed an extraordinarily good observation point, was one of the gains in this direction. The Fifteenth Division had been driven back to the western side of Hill 70, and to the line of the Lens-Hulluch-La Bassée road. The Seventh and Ninth Divisions had fallen back from Haisnes, but they still held the western outskirts of Hulluch, the edge of St. Élie, the Quarries, and Fosse 8. It was at this end of the line that the situation was most dangerous, for the failure of the Second Division to get forward had left a weak flank upon the north, which was weaker because the heavily-gunned German position of Auchy lay to the north-west of it in a way that partially enfiladed it.

The struggle was particularly desperate round the slag-heaps which were known as Fosse 8. This position was held all day by the 5th Camerons, the 8th Black Watch, and the 7th Seaforths of the 26th Brigade, the remaining battalion of which, the 8th Gordons, were with the bulk of the 27th Brigade in the direction of Haisnes. These three battalions, under a murderous fire from the Auchy guns and from the persistent bombers, held on most tenaciously till nightfall. When the welcome darkness came, without bringing them the longed-for supports, the defenders had shrunk to 600 men, but their grip of the position was not relaxed, and they held it against all attacks during the night. About five next morning the 73rd Brigade of the Twenty-fourth Division a unit straight from home pushed up to their help under circumstances to be afterwards explained, and shared their great dangers and losses during the second day of the fighting.

The battalions of the Ninth Division which had got as far as the outskirts of Haisnes held on there until evening. By that time no reinforcements had reached them and they had lost very heavily. Both their flanks were turned, and at nightfall they were driven back in the direction of the Quarries, which was held by those men of the Seventh Division (mostly of the 22nd Brigade) who had also been compelled to fall back from Hulluch. During the night this position was wired by the 54th Company of Royal Engineers, but the Germans, by a sudden and furious attack, carried it, driving out the garrison and capturing some of them, among whom was General Bruce, the Brigadier of the 27th Brigade. After the capture of the Quarries, the flanks of the 27th Brigade were again turned, and it was compelled to return as far as the old German front line. The 20th Brigade had fallen back to the same point. These misfortunes all arose from the radically defective position of the northern British line, commanded as it was by German guns from its own left rear, and unprotected at the flank.

Whilst this set-back had occurred upon the left of the attack, the right had consolidated itself very firmly. The position of the Forty-seventh Division when darkness fell was that on their right the 140th Brigade had a strong grip of part of the Double Grassier. On their left the 19th Battalion (St. Pancras), which had lost its Colonel, Collison-Morley, and several senior officers, was holding South-east Loos in the rear of the right flank of the Fifteenth Division. The 20th was holding the Loos Chalk Pit, while the 17th and 18th were in the German second-line trenches.

There is reason to believe that the rapid dash of the stormers accomplished results more quickly than had been thought possible. The Twenty - first and Twenty-fourth Divisions were now brought up, as Sir John French clearly states in his dispatch, for a specific purpose: “To ensure the speedy and effective support of the First and Fourth Corps in the case of their success, the Twenty-first and Twenty-fourth Divisions passed the night of the 24th and 25th on the line of Beuvry Noeux-les-Mines.”

Leaving the front line holding hard to, or in some cases recoiling from, the advanced positions which they had won, we will turn back and follow the movements of these two divisions. It is well to remember that these divisions had not only never heard the whistle of a bullet, but they had never even been inside a trench, save on some English down-side. It is perhaps a pity that it could not be so arranged that troops so unseasoned in actual warfare should occupy some defensive line, while the older troops whom they relieved could have marched to battle. Apart, however, from this inexperience, which was no fault of their own or of their commanders, there is no doubt at all that the men were well-trained infantry and full of spirit. To bring them to the front without exciting attention, three separate night marches were undertaken, of no inordinate length, but tiring on account of the constant blockings of the road and the long waits which attended them. Finally they reached the point at which Sir John French reported them in his dispatch, but by ill-fortune their cookers came late, and they were compelled in many cases to move on again without a proper meal. After this point the cookers never overtook them, and the men were thrown back upon their iron rations. Providence is not a strong point of the British soldier, and it is probable that with more economy and foresight at the beginning these troops would have been less exhausted and hungry at the end. The want of food, however, was not the fault of the supply services.

The troops moved forward with no orders for an instant attack, but with the general idea that they were to wait as a handy reserve and go forward when called upon to do so. The 62nd Brigade of the Twenty-first Division was sent on first about eleven o’clock, but the other brigades were not really on the road till much later. The roads on which they moved those which lead through Vermelles to Hulluch or to Loos were blocked with traffic: guns advancing, ambulances returning, troops of all sorts coming and going, Maltese carts with small-arm ammunition hurrying forward to the fighting-line. The narrow channel was choked with the crowd. The country on either side was intersected with trenches and laced with barbed wire. It was pouring with intermittent showers. The soldiers, cold, wet, and hungry, made their way forward with many stoppages towards the firing, their general direction being to the centre of the British line.

“As we got over this plain,” writes an officer, “I looked back, and there was a most extraordinary sight; as far as you could see there were thousands and thousands of our men coming up. You could see them for miles and miles, and behind them a most colossal thundercloud extending over the whole sky, and the rain was pouring down. It was just getting dark, and the noise of our guns and the whole thing was simply extraordinary.”

Early on the march the leading brigade, the 73rd, was met by a staff officer of the First Army, who gave the order that it should detach itself, together with the 129th Field Company of Sappers, and hasten to the reinforcement of the Ninth Division at Fosse 8. They went, and the Twenty- fourth Division knew them no more. The other two brigades found themselves between 9 and 10 P.M. in the front German trenches. They had been able to deploy after leaving Vermelles, and the front line were now in touch with the 63rd Brigade of the Twenty-first Division upon the right, and with the 2nd Welsh Regiment, who represented the right of the 3rd Brigade of the First Division, upon their left. The final orders were that at eleven o’clock next day these three divisions First, Twenty-fourth, and Twenty-first were to make a united assault past Hulluch, which was assumed to be in our hands, and on to the main German line. This, then, was the position of the reserves on the night of September 25-26.

It was a nightmare night in the advanced line of the Army. The weather had been tempestuous and rainy all day, though the men had little time to think of such matters. But now they were not only tired and hungry, but soaked to the skin. An aggressive enemy pelted them with bombs from in front, and their prospects seemed as black as the starless sky above them. It is, however, at such a time that the British soldier, a confirmed grumbler in his hours of ease, shows to the best advantage. The men knew that much ground had been gained. They had seen prisoners by hundreds throwing up their hands, and had marked as they rushed past them the vicious necks of the half-buried captured cannon. It was victory for the Army, whatever might be their own discomfort. Their mood, therefore, was hilarious rather than doleful, and thousands of weary Mark Tapleys huddled under the dripping ledges of the parapets. “They went into battle with their tails right up, and though badly mauled have their tails up still.” So wrote the officer of a brigade which had lost more than half its effectives.