V. The Battle of the Somme

From July 2 to July 14, 1916

General situation—Capture of La Boiselle by Nineteenth Division—Splendid attack by 36th Brigade upon Ovillers —Siege and reduction of Ovillers—Operations at Contalmaison —Desperate fighting at the Quadrangle by Seventeenth Division — Capture of Mametz Wood by Thirty-eighth Welsh Division—Capture of Trones Wood by Eighteenth Division

The terrible fighting just described, during which the German line was broken at its southern end, was but the opening of a most desperate battle, which extended of the over many months. This, while it cost very heavy losses on both sides, exacted such a toll from the Germans in prisoners and lost material, as well as in casualties, that it is probable that their army would have been largely disorganised had not the wet weather of October come to hamper the operations. As it was, the letters of the soldiers and the intercepted messages of the Generals show an amount of demoralisation which proves the mighty pressure applied by the allied armies. It was a battle which was seldom general throughout the curve into which the attackers had encroached, but which confined itself to this or that limited objective —to the north, to the east, or to the south, the blow falling the more suddenly, since during the whole of this time the Allies preserved the command of the air to an extent which actually enabled them to push their guns forward across the open. Sometimes it was a fortified village which was carried. Sometimes it was the trenches between villages, so that the garrisons might feel in danger of being cut off. Sometimes—the worst obstacle of all—it was one of the patches of wood dotted over the country-side, which had to be cleared of the enemy’s stubborn infantry and machine-gunners. But whatever the task might be, it may be stated generally that it was always carried out, if not at the first, then at the second, third, or some subsequent attempt. It may also be said that never once during all that time did a yard of ground which had been taken by the Allies pass permanently back to the enemy. Before the winter had fallen more than forty villages had been carried and held by the attack—but not one by the counter-attack. The losses were heavy, sometimes very heavy, but so perfect now was the co-ordination between infantry and guns, and so masterful the allied artillery, that it is highly probable that at last the defence was losing as many as the attack. Those deep ravines which had enabled the Germans to escape the effects of the early bombardments no longer existed in the new lines, and the superficial ditches which now formed the successive lines of defence offered little protection from a fire directed by a most efficient air service. On the other hand, since the German air service had been beaten out of the sky, the sight of the German gunners was dim, and became entirely blind when by their successive advances the Allies had pushed them over the low ridges which formed their rearward positions. The map, however skilfully used, is a poor substitute for the observation officer and the aeroplane.

Standing on the edge of this welter, and gazing at this long haze info which vigorous divisions continually plunge, relieving exhausted units, only to stagger out in their turn, rent and torn, while yet others press to the front, one feels appalled at the difficulty of following such complex operations and of conveying them clearly and in their due order to the mind of the reader. Some fixed system must evidently be followed if the narrative is to remain intelligible and the relation of the various actions to each other to be made evident. Therefore the course of events will still, so far as possible, be traced from the north, and each incident be brought to some sort of natural pause before we pass onwards down the line. We can at once eliminate the whole northern portion of the British line from the Gommecourt salient down to Albert, since for that long stretch attack had changed definitely to defence, and we start our narrative from the south of the Albert-Bapaume road. From that point four villages immediately faced the old British line, and each was now a centre of fighting. From the north they were La Boiselle, Fricourt, Mametz, and Montauban. The latter had been held against a strong counter-attack on the early morning of July 2, and it was firmly in the possession of the Thirtieth Division. Mametz was held by the Seventh Division, who were pushing on to the north, driving a weak resistance before them. Fricourt had been deserted by the morning of July 2, and had been occupied by the Seventeenth Division, who also at once pushed on towards the woodlands behind. La Boiselle was closely assailed with part of the Thirty-fourth Division to the south of it, and the Twelfth and Nineteenth Divisions with other troops all round it. These four villages and the gaps between them represented the break in the German front line.

The second German main line ran through the Bazentins and Longueval, and it was reached and carried by the British Army upon July 14. The intervening fortnight between the battle of the front and of the second line was occupied in clearing the many obstacles, consisting for the most part of woods and subsidiary trenches which filled the space between the two lines, and also in attacking the two villages of Ovillers and Contalmaison, which hampered operations upon the left wing. It will help the reader very much to understand these apparently complex movements if he will realise that they divide themselves into three distinct groups of activity, counting from the north of the line. The first group is concerned with the capture of Ovillers, and in it the Twelfth, Nineteenth, Thirty-second, and Twenty-fifth Divisions are concerned. The second group is connected with the capture of the strong position which is bastioned by Contalmaison upon one side and Mametz Wood at the other, with the Quadrangle system of trenches between. In this very severe conflict the Twenty-third, Seventeenth, Seventh, and Thirty-eighth Divisions were engaged. Finally there is the group of operations by which the right wing was advanced through Bernafoy Wood and up to Trones Wood. In these, the Ninth, Thirtieth, and Eighteenth Divisions were chiefly concerned. We shall now take each of these in turn, beginning with the northern one, the taking of Ovillers, and carrying each narrative to a definite term. Before embarking upon this account it should be mentioned that the of the two northern corps of Rawlinson’s army—the Eighth and Tenth—were from now onwards detached as a separate Fifth Army under Sir Hubert Gough, one of the most rising commanders in the Service. The functions of this Army were to hold the line from La Boiselle to Serre, and to form a defensive flank and pivot for the Third, Fifteenth, and Thirteenth Corps to the south.

We shall first follow the further fortunes of the troops which operated in the north. Upon July 3 there was a short but severe action upon that part of the old British line immediately to the left of the gap which had been broken. In this action, which began at 6 A.M., the Thirty-second Division, already greatly weakened by its exertions two days before, together with the 75th Brigade, lent them by the Twenty-fifth Division, tried to widen the rent in the’ German line by tearing open that portion of it which had been so fatal to the Eighth Division. The attack failed, however, though most bravely delivered, and the difficulties proved once more to be unsurmountable. The attempt cost us heavy casualties, a considerable proportion of which fell upon the 75th Brigade, especially upon the 11th Cheshires, whose colonel was killed, and upon the 2nd South Lancashires, who ran into wire and were held up there. The 8th Borders reached their objective, but after one-and-a-half hours were forced to let go of it. The operation proved that whatever misfortunes had befallen the Germans to the south, they were still rooted as firmly as ever in their old positions. The same lesson was to be taught us on the same morning at an adjacent portion of the line.

This episode was at the immediate south of the unsuccessful attack just described. It has already been stated that the Twelfth, the English division which had seen so much hard fighting at Loos, had taken over part of the trenches of the Eighth Division, and so found themselves facing Ovillers. Their chances of a successful advance upon the village were increased by the fact that the Nineteenth Division, after hard fighting, had got into La Boiselle to the south, and so occupied a flank to their advance.

Some further definition is required as to the situation at La Boiselle, how it was brought about, and its extreme importance to the general plan of operations. When the left of the Thirty-fourth Division had failed to hold the village, while some mixed units of the right brigade had established themselves within the German lines as already narrated, it became very vital to help them by a renewed attempt upon the village itself. For this purpose the Nineteenth Division had moved forward, a unit which had not yet been seriously engaged. It was under the command of a fighting Irish dragoon, whose whimsical expedient for moving forwards the stragglers at St. Quentin has been recorded in a previous volume. On the evening of July 1, one battalion of this division, the 9th Cheshires, had got into the German front line trench near the village, but they were isolated there and hard put to it to hold their own during a long and desperate night. On the following afternoon, about 4 o’clock, two of their fellow-battalions of the 58th Brigade, the 9th Royal Welsh Fusiliers and the 6th Wilts, charged suddenly straight across the open at the village, while by a clever device the British barrage was turned elsewhere with the effect of misleading the German barrage which played upon the wrong area. By 9 P.M. on July 2 the south end of the village had been captured, but the resistance was still very fierce. Early next morning the whole of the division was drawn into this street fighting, and gradually the Germans were pushed back. There was one desperate counter-attack during which the British line was hard put to it to hold its own, and the house-to-house fighting continued throughout the whole day and night. Two British colonels, one of the 7th South Lancashires and the other of the 8th Gloucesters, particularly distinguished themselves in this close fighting. The latter, a dragoon like his commander, was a hard soldier who had left an eye in Somaliland and a hand at Ypres, but the sight of him in this day of battle, tearing out the safety-pin of bombs with his teeth and hurling them with his remaining hand, was one which gave heart to his men. Slowly the Germans were worn down, but the fighting was fierce and the British losses heavy, including three commanding officers, Wedgwood of the North Staffords, Royston Piggott of the 10th Worcesters, and Heath of the 10th Warwicks, the first two killed, the latter wounded. In the midst of the infantry fighting a single gun of the 19th Battery galloped with extraordinary gallantry right into the village and engaged the enemy point-blank with splendid effect. For this fine performance Captain Campbell and ten men of the gun’s crew received decorations. By the evening of the 6th the whole village was solidly consolidated by the Nineteenth Division, they had broken up a strong counter-attack from the direction of Pozières, and they had extended their conquest so as to include the redoubt called Heligoland. We must turn, however, to the attack which had in the meanwhile been prepared upon the line to the immediate north of La Boiselle by the Twelfth Division.

This attack was carried out at three in the morning of July 7 by the 35th and the 37th Brigades. The fighting line from the right consisted of the 5th Berks, 7th Suffolks, 6th Queen’s Surrey, and 6th West Kent, with the other battalions in close support. Unhappily, there was a group of machine-guns in some broken ground to the north of La Boiselle, which had not yet been reached by the Nineteenth Division, and the fire of these guns was so deadly that the battalions who got across were too weak to withstand a counter-attack of German bombers. They were compelled, after a hard struggle, to fall back to the British line. One curious benefit arose in an unexpected way from the operation, for part of the 9th Essex, losing its way in the dark, stumbled upon the rear of the German defenders of the northern edge of La Boiselle, by which happy chance they took 200 prisoners, helped the Nineteenth in their task, and participated in a victory instead of a check.

It was evident that before the assault was renewed some dispositions should be made to silence the guns which made the passage perilous. With this in view, another brigade, the 74th from the Twenty-fifth Division, was allotted to the commander of the Twelfth Division, by whom it was placed between his own position and that held by the Nineteenth at La Boiselle. It was arranged that these fresh troops should attack at eight o’clock in the morning of of the July 7, approaching Ovillers from the south, and overrunning the noxious machine-guns, while at 8:30 the 36th Brigade, hitherto in reserve, should advance upon Ovillers from the west. By this difference of half an hour in the attack it was hoped that the 74th would have got the guns before the 36th had started.

After an hour’s bombardment the signal was given and the 74th Brigade came away with a rush, headed by the 13th Cheshires and 9th North Lancashires, with the 2nd Irish Rifles and 11th Lancashire Fusiliers in support. The advance found the Germans both in front and on either flank of them, but in spite of a withering fire they pushed on for their mark. Nearly every officer of the 13th Cheshires from Colonel Finch down to Somerset, the junior subaltern, was hit. Half-way between La Boiselle and Ovillers the attack was brought to a halt, and the men found such cover as they could among the shell holes. Their supporting lines had come up, but beyond some bombing parties there was no further advance during the day. Fifty yards away the untaken machine-gun emplacements lay in front of them, while Ovillers itself was about 600 yards distant upon their left front.

In the meantime, after waiting half an hour, the 36th Brigade had advanced. The machine-guns were, however, still active on either flank of them, and on their immediate front lay the rubbish-heap which had once been a village, a mass of ruins now. But amid those ruins lay the Fusiliers of the Prussian Guard—reputed to be among the best soldiers in Europe, and every chink was an embrasure for rifle or machine-gun. The advance was one which may have been matched in the glorious annals of the British infantry, but can never have been excelled. The front line consisted of the 8th and 9th Royal Fusiliers, one upon each wing, the 7th Sussex in the centre, and the 11th Middlesex in support—south-country battalions all. They had lain waiting for the signal in trenches which were beaten to pieces by a terrific German shelling. There were considerable casualties before the first man sprang from fire-step to parapet. As they crossed No Man’s Land bullets beat upon them from every side. The advance was rendered more frightful by the heavy weather, which held down the fumes of the poison shells, so that the craters in which men took refuge were often found to be traps from which they never again emerged. Many of the wounded met their death in this terrible fashion. Still the thin lines went forward, for nothing would stop them save death or the voice of their company officers. They were up and over the first German line. A blast of fire staggered them for a moment, and then with a splendid rally they were into the second trench, and had seized the line of hedges and walls which skirt the western edge of the village. Five hundred men were left out of those who had sprung from the British trench; but the 500 still went forward. The two Fusilier battalions had hardly the strength of a company between them, and the leaders were all down—but every man was a leader that day. Their spirit was invincible. An officer has recorded how a desperately wounded man called out, “Are the trenches taken, sir?” On hearing that they were, he fell back and cried, “Thank God! for nothing else matters.” In the centre the Sussex men still numbered nearly 300, and their colonel aided and directed while they consolidated the ground. One hundred and fifty were hit as they did so, but the handful who were left defied every effort of shell, bomb, or bayonet to put them out. A lodgment had been made, and nothing now could save the village. By a wise provision, seeing that no supplies could reach them, every man had been loaded up with twenty bombs, and had been instructed to use every captured German bomb or cartridge before any of his own. As dusk fell, two companies of the supporting Middlesex battalion were sent up, under heavy fire, to thicken the line, which was further strengthened next day by two battalions from the 37th Brigade, while the 75th Brigade prolonged it to the south. In the morning of July 9 the Twelfth Division, sorely stricken but triumphant, was drawn from the line, leaving the northern half of the Ovillers front to the Thirty-second Division and the southern half to the Twenty-fifth, the scattered brigades of which were now reunited under one general.

That commander had found himself during these operations in a difficult position, as the 74th Brigade had been moved from him and allotted to the Twelfth Division, and the Seventy-fifth by the Thirty-second Division. None the less, he had carried on vigorously with his remaining Brigade—the 7th, and had enlarged and strengthened the British position in the Leipzig salient. During July 5 and 6 the 1st Wilts and the 3rd Worcesters had both broadened and extended their fronts by means of surprise attacks very well carried out. On the 7th they pushed forward, as part of the general scheme of extension upon that day, advancing with such dash and determination that they got ahead of the German barrage and secured a valuable trench.

When upon Sunday, July 9, the Thirty-second Division had entirely taken over from the Twelfth on the west of Ovillers, the 14th Brigade were in the post of honour on the edge of the village. The 2nd Manchesters on the left and the 15th Highland Light Infantry on the right, formed the advanced line with the 1st Dorsets in support, while the 19th Lancashire Fusiliers were chiefly occupied in the necessary and dangerous work of carrying forward munitions and supplies. Meanwhile, the pioneer battalion, the 17th Northumberland Fusiliers, worked hard to join up the old front trench with the new trenches round Ovillers. It should be mentioned, as an example of the spirit animating the British Army, that Colonel Pears of this battalion had been invalided home for cancer, that he managed to return to his men for this battle, and that shortly afterwards he died of the disease.

On July 10 at noon the 14th Brigade advanced upon Ovillers from the west, carrying on the task which had been so well begun by the 36th Brigade. The assailants could change their ranks, but this advantage was denied to the defenders, for a persistent day and night barrage cut them off from their companions in the north. None the less, there was no perceptible weakening of the defence, and the Prussian Guard lived up to their own high traditions. A number of them had already been captured in the trenches, mature soldiers of exceptional physique. Their fire was as murderous as ever, and the 2nd Manchesters on the north or left of the line suffered severely. The 15th Highlanders were more fortunate made good progress. The situation had been improved by an advance at 9 P.M. upon this date, July 10, by the 2nd Inniskilling Fusiliers from the Sixth Division, higher up the line, who made a lodgment north-west of Ovillers, which enabled a Russian sap to be opened up from the British front line. The Inniskillings lost 150 men out of two companies engaged, but they created a new and promising line of attack.

The British were now well into the village, both on the south and on the west, but the fighting was closer and more sanguinary than ever. Bombardments alternated with attacks, during which the British won the outlying ruins, and fought on from one stone heap to another, or down into the cellars below, where the desperate German Guardsmen fought to the last until overwhelmed with bombs from above, or stabbed by the bayonets of the furious stormers. The depleted 74th Brigade of the Twenty-fifth Division had been brought back to its work upon July 10, and on the 12th the 14th Brigade was relieved by the 96th of the same Thirty-second Division. On the night of July 12 fresh ground was gained by a surge forward of the 2nd South Lancashires of the 75th Brigade, and of the 19th Lancashire Fusiliers, these two battalions pushing the British line almost up to Ovillers Church. Again, on the night of the 13th the 3rd Worcesters and 8th Borders made advances, the latter capturing a strong point which blocked the way to further progress. On the 14th, however, the 10th Cheshires had a set-back, losing a number of men. Again, on the night of July 14 the 1st Dorsets cut still further into the limited area into which the German resistance had been compressed. On the night of the 15th the Thirty-second Division was drawn out, after a fortnight of incessant loss, and was replaced by the Forty-eighth Division of South Midland Territorials, the 143rd Brigade consisting entirely of Warwick battalions, being placed under the orders of the General of the Twenty-fifth Division. The village, a splintered rubbish-heap, with the church raising a stumpy wall, a few feet high, in the middle of it, was now very closely pressed upon all sides. The German cellars and dug-outs were still inhabited, however, and within them the Guardsmen were as dangerous as wolves at bay. On the night of July 15-16 a final attack was arranged. It was to be carried through by the 74th, 75th, and 143rd Brigades, and was timed for 1 A.M. For a moment it threatened disaster, as the 5th Warwicks got forward into such a position that they were cut off from supplies, but a strong effort was made by their comrades, who closed in all day until 6 P.M., when the remains of the garrison surrendered. Two German officers and 125 men were all who remained unhurt in this desperate business; and it is on record that one of the officers expended his last bomb by hurling it at his own men on seeing that they had surrendered. Eight machine guns were taken. It is said that the British soldiers saluted the haggard and grimy survivors as they were led out among the ruins. It was certainly a very fine defence. After the capture of the village, the northern and eastern outskirts were cleared by the men of the Forty-eighth Territorial Division, which was partly accomplished by a night attack of the 4th Gloucesters. From now onwards till July 29 this Division was engaged in very arduous work, pushing north and and east, and covering the flank of the Australians in their advance upon Pozières.

So much for the first group of operations in the intermediate German position. We shall now pass to the second, which is concerned with the strong fortified line formed by the Quadrangle system of trenches between Contalmaison upon our left and Mametz Wood upon our right.

It has been mentioned under the operations of the Twenty-first Division in the last chapter that the 51st Brigade passed through the deserted village of Fricourt upon the morning of July 2, taking about 100 prisoners.

On debouching at the eastern end they swung to the right, the 7th Lincolns attacking Fricourt Wood, and the 8th South Staffords, Fricourt Farm. The wood proved to be a tangle of smashed trees, which was hardly penetrable, and a heavy fire stopped the Lincolns. The colonel, however, surmounted the difficulty by detaching an officer and a party of men to outflank the wood, which had the effect of driving out the Germans. The South Staffords were also successful in storming the farm, but could not for the moment get farther. Several hundreds of prisoners from the 111th Regiment and three guns were captured during this advance, but the men were very exhausted at the end of it, having been three nights without rest. Early next day (July 3) the advance was resumed, the 51st Brigade still to the fore, working in co-operation with the 62nd Brigade of the Twenty-first Division upon their left. By hard fighting, the Staffords, Lincolns, and Sherwoods pushed their way into Railway Alley and Railway Copse, while the 7th Borders established themselves in Bottom Wood. The operations came to a climax when in the afternoon a battalion of the 186th Prussian Regiment, nearly 600 strong, was caught between the two Brigades in Crucifix Trench and had to surrender; altogether the 51st Brigade had done a very strenuous and successful spell of duty. The ground gained was consolidated by the 77th Field Company, Royal Engineers.

The 62nd Brigade of the Twenty-first Division, supported by the 63rd, had moved parallel to the 51st Brigade, the 1st Lincolns, 10th Yorkshires, and two battalions of Northumberland Fusiliers advancing upon Shelter Wood and carrying it by storm. It was a fine bit of woodland fighting, and the first intimation to the Germans that their fortified forests would no more stop British infantry than their village strongholds could do. The enemy, both here and in front of the Seventeenth Division, were of very different stuff from the veterans of Ovillers, and surrendered in groups as soon as their machine-guns had failed to stop the disciplined rush of their assailants. After this advance, the Twenty-first Division was drawn out of line for a rest, and the Seventeenth extending to the left was in touch with the regular 24th Brigade, forming the right of Babington’s Twenty-third Division, who were closing in upon Contalmaison. On the right the 17th were in touch with the 22nd Brigade of the Seventh Division, which was pushing up towards the dark and sinister clumps of woodland which barred their way. On the night of July 5 an advance was made, the Seventh Division upon Mametz Wood, and the Seventeenth upon the Quadrangle Trench, connecting the wood with Contalmaison. The attack upon the wood itself had no success, though the 1st Royal Welsh Fusiliers reached their objective, but the 52nd Brigade was entirely successful at Quadrangle Trench, where two battalions—the 9th Northumberland Fusiliers and 10th Lancashire Fusiliers—crept up within a hundred yards unobserved and then carried the whole position with a splendid rush. It was at once consolidated.

The Twenty-third Division had advanced upon the left and were close to Contalmaison. On the night of July 5 the Seventh Division was drawn out and the Thirty-eighth Welsh Division took over the line which faced Mametz Wood.

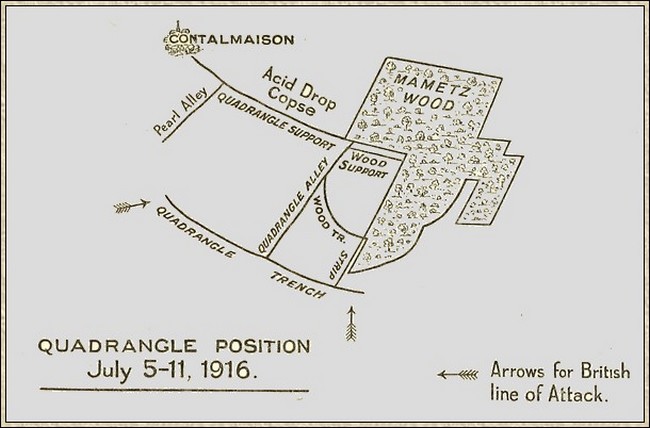

The Seventeenth Division, after its capture of the Quadrangle Trench, was faced by a second very dangerous and difficult line called the Quadrangle Support, the relative position of which is shown upon the diagram on the next page.

It is clear that if either Mametz Wood or Contalmaison were to fall, this trench would become untenable for the Germans, but until those two bastions, or at least one of them, was in our hands, there was such a smashing fire beating down upon an open advance of 600 yards, that no harder task could possibly be given to a Division. The trench was slightly over the brow of a slope, so that when the guns played upon it the garrison were able to sUp quickly away and take refuge in Mametz Wood, coming back again in time to meet an assault which they were well aware could only be delivered by troops which had passed through an ordeal of fire which must shake and weaken them.

Quadrangle Position, July 5-11, 1916

It seemed that the best chance to bring a striking force up to the trench was to make the attempt at night, so at 2 A.M. of July 7 the 9th Northumberland Fusiliers and 10th Lancashire Fusiliers, the same battalions which had already taken Quadrangle Trench, advanced through the darkness of an inclement night upon their objective. The enemy proved, however, to be in great force, and their trench was stuffed with men who were themselves contemplating an attack. A party of Lancashire Fusiliers got into Pearl Alley, which is on the left near Contalmaison, but the village stands on a slight eminence, and from it the trench and the approaches can be swept by fire. The British attack was driven back with loss, and was followed up by the 9th Grenadiers of the Prussian Guard, who were in turn driven back by the left of the British line, consisting of the 10th Lancashire Fusiliers and some of the 1st Worcesters. In the morning another attempt was made upon Quadrangle Support, this time by the 9th West Ridings and the 12th Manchesters. Small parties got up to Acid Drop Copse, close to Contalmaison, but they were too weak to hold on. At the end of this attack the 52nd Brigade, which had been so badly mauled, was drawn out and the 51st put back in its place.

This severe fighting at the Quadrangle was part of a wider action, which was to include an attack by the Twenty-third Division upon Contalmaison and an attack by the Thirty-eighth upon Mametz Wood. The Contalmaison attack won its way into the north-west side of the village at 11 o’clock on the morning of July 7, but by 12 o’clock it had been held and eventually repulsed. By 4:30 the 24th Brigade of the Twenty-third Division, which was on the immediate left of the Seventeenth Division, had been driven of the back to its trenches, the 1st Worcesters, 2nd East Lancashires, and 2nd Northamptons suffering heavily.

Whilst the Contalmaison attack had failed upon the left, that upon Mametz Wood had no better success upon the right. It was to have been carried out by the Thirty-eighth Welsh Division, but in its approach such opposition was encountered to the wood that the 16th Welsh (City of Cardiff) and 10th South Wales Borderers could not get forward. Meanwhile, the 50th Brigade from the Seventeenth Division had been told off to co-operate with this attack, and naturally found themselves with their right flank in the air, the 7th East Yorks suffering severely in consequence. None the less, some advance was made upon this side.

In the night of July 7 a third attack was made upon Quadrangle Support, with no better result than the others. On this occasion the 51st Brigade had relieved the 52nd, and it was the 10th Sherwood Foresters which endured the heavy losses, and persevered until they were within bomb-throw of their objective, losing Major Hall Brown, a gallant Ceylon planter, and many officers and men. At the same hour the 50th Brigade had again tried to gain ground in the direction of Mametz Wood, but had failed on account of uncut wire. The military difficulties of the situation during this day were greatly enhanced by the state of the ground, owing to most unseasonable heavy rain, which left four feet of mud in some of the trenches. Altogether, when one considers the want of success at Ovillers, the repulse at Contalmaison, the three checks in one day at the Quadrangle, and the delay of the attack on Mametz Wood, the events of July 7 showed that the task of the British, even inside a broken German line, was still a very heavy one. General Horne upon the line and Sir Douglas Haig behind it must both have felt the strain that night.

At six in the morning of July 8 the undefeatable Seventeenth Division was again hard at work encompassing the downfall of its old opponents in Quadrangle Support. Since it could not be approached above ground, it was planned that two brigades, the 51st and the 50th, should endeavour to bomb their way from each side up those trenches which were in their hands. It is wonderful that troops which had already endured so much, and whose nerve might well be shattered and their hearts broken by successive failures, should still be able to carry out a form of attack which of all others call for dash and reckless courage. It was done, none the less, and with some success, the bombers blasting their way up Pearl Alley on the left to the point where it joins on to the Quadrangle Support. The bombers of the 7th Lincolns did particularly well. “Every attempted attack by the Boche was met by them with the most extraordinary Berserker fury. They utterly cowed the enemy.” So wrote an experienced spectator. On the right the 50th Brigade made some progress also up Quadrangle Alley. Artillery fire, however, put a term to the advance in both instances, the guns of Contalmaison dominating the whole position. In the evening a fresh bombing attack was made by the same troops, whose exertions seem really to have reached the limit of human capacity. This time the 7th Borders actually reached Quadrangle Support, but were unable to get farther. The same evening some of the 50th Brigade bombed down Wood Trench towards Mametz Wood, so as to facilitate the coming attack by the Thirty-eighth Division. On July 9 both Brigades again tried to bomb their way into Quadrangle Support, and were again held up by the enemy’s fire. This was the sixth separate attempt upon the same objective by the same soldiers—an example surely of the wonderful material of which the New Armies were composed.

But their labours were not yet done. Though both brigades were worn to shadows, it was still a point of honour to hold to their work. At 11:20 that night a surprise attack was made across the open under the cover of night. The 8th South Staffords on the left—charging with a yell of “Staffords!”—reached the point where Pearl Alley joins the Quadrangle Support (see Diagram), and held on most desperately. The 50th Brigade on the right were checked and could give no assistance. The men upon the left strove hard to win their way down Quadrangle Support, but most of the officers were down, the losses were heavy, and the most that they could do was to hold on to the junction with Pearl Alley. The 50th were ready to go forward again to help them, and the Yorkshire men were already on the move; but day was slowly breaking and it was doubtful if the trench could be held under the guns of Contalmaison. The attack upon the right was therefore stopped, and the left held on as best it might, the South Staffords, having lost grievously, nearly all their officers, including the Adjutant, Coleridge, being on the ground.

We may now leave this heroic tragedy of the of the Quadrangle and turn our attention to what had been going on at Mametz Wood upon the right, which was really the key to the situation. It has already been stated that the wood had been attacked in vain by a brigade of the Seventh Division, and that the Thirty-eighth Welsh Division had found some difficulty in even approaching it. It was indeed a formidable obstacle upon the path of the army. An officer has described how he used to gaze from afar upon the immense bulk, the vast denseness and darkness of Mametz Wood, and wonder, knowing the manifold dangers which lurked beneath its shadows, whether it was indeed within human power to take it. Such was the first terrible task to which the Welshmen of the New Army were called. It was done, but one out of every three men who did it found the grave or the hospital before the survivors saw the light shine between the further tree-trunks.

As the Welshmen came into the line they had the Seventeenth Division upon their left, facing Quadrangle Support, and the Eighteenth upon their right at Caterpillar Wood. When at 4:15 on the morning of July 10 all was ready for the assault, the Third Division had relieved the Eighteenth on the right, but the Seventeenth was, as we have seen, still in its position, and was fighting on the western edge of the wood.

The attack of the Welshmen started from White Trench, which lies south-east of the wood and meanders along the brow of a sharp ridge. Since it was dug by the enemy it was of little use to the attack, for no rifle fire could be brought to bear from it upon the edge of the wood, while troops coming over the hill and down the slope were dreadfully exposed. Apart from the German riflemen and machine-gunners, who lay thick among the shell-blasted stumps of trees, there was such a tangle of thick undergrowth and fallen trunks lying at every conceivable angle that it would take a strong and active man to make his way through the wood with a fowling-piece for his equipment and a pheasant for his objective. No troops could have had a more desperate task—the more so as the German second line was only a few hundred yards from the north end of the wood, whence they could reinforce it at their pleasure.

The wood is divided by a central ride running north and south. All to the west of this was allotted to the 113th Brigade, a unit of Welsh Fusilier battalions commanded by a young brigadier who is more likely to win honour than decorations, since he started the War with both the V.C. and the D.S.O. The 114th Brigade, comprising four battalions of the Welsh Regiment, was to carry the eastern half of the wood, the attack being from the south. The front line of attack, counting from the right, consisted of the 13th Welsh (2nd Rhonddas), 14th Welsh (Swansea), with its left on the central ride, and 16th Royal Welsh Fusiliers in the van of the 113th Brigade. About 4:30 in the morning the barrage lifted from the shadowy edge of the wood, and the infantry pushed forward with all the Cymric fire which burns in that ancient race as fiercely as ever it has done, as every field of manly sport will show. It was a magnificent spectacle, for wave after wave of men could be seen advancing without hesitation and without a break over a distance which in some places was not less than 500 yards.

The Swansea men in the centre broke into the wood without a check, a lieutenant of that battalion charging down two machine-guns and capturing both at the cost of a wound to himself. The 13th on the right won their way also into the wood, but were held for a time, and were reinforced by the 15th (Carmarthens). Here for hours along the whole breadth of the wood the Welsh infantry strove desperately to crawl or burst through the tangle of tree-trunks in the face of the deadly and invisible machine-guns. Some of the 15th got forward through a gap, but found themselves isolated, and had great difficulty in joining up with their own battle line once more. Eventually, in the centre and right, the three battalions formed a line just south of the most southern cross ride from its junction with the main ride.

On the left, the 16th Welsh Fusiliers had lost heavily before reaching the trees, their colonel, Garden, falling at the head of his men. The circumstances of his death should be recorded. His Welsh Fusiliers, before entering action, sang a hymn in Welsh, upon which the colonel addressed them, saying, “Boys, make your peace with God! We are going to take that position, and some of us won’t come back. But we are going to take it.” Tying his handkerchief to his stick he added, “This will show you where I am.” He was hit as he waved them on with his impromptu flag; but he rose, advanced, was hit again, and fell dead.

Mametz Wood

Thickened by the support of the 15th Royal Welsh Fusiliers, the line rushed on, and occupied the end of the wood until they were abreast of their comrades on the right. Once among the trees, all cohesion was lost among the chaos of tangled branches and splintered trunks, every man getting on as best he he might, with officers rallying and leading forward small groups, who tripped and scrambled onwards against any knot of Germans whom they could see. On this edge of the wood some of the Fusiliers bombed their way along Strip Trench, which outlines the south-western edge, in an endeavour to join hands with the 50th Brigade on their left. At about 6:30 the south end of the wood had been cleared, and the Welshmen, flushed with success, were swarming out at the central ride. A number of prisoners, some hale, some wounded, had been taken. At 7 o’clock the 113th were in touch with the 114th on the right, and with the 50th on the left.

Further advance was made difficult by the fact that the fire from the untaken Wood Support Trench upon the left swept across the ride. The losses of the two Fusilier battalions had been so heavy that they were halted while their comrades of the 13th Royal Welsh Fusiliers, under Colonel Flower, who was killed by a shell, attacked Wood Support—eventually capturing the gun which had wrought such damage, and about 50 Germans. This small body had succeeded, as so often before and since, in holding up a Brigade and disorganising an advance. Until the machine-gun is checkmated by the bullet-proof advance, the defensive will maintain an overpowering and disproportionate advantage.

The 10th Welsh had now come up to reinforce the left of the 114th Brigade, losing their colonel, Rickets, as they advanced into the wood. The 19th Welsh Pioneer Battalion also came forward to consolidate what had been won. There was a considerable pause in the advance, during which two battalions — the 17th Welsh Fusiliers and the 10th South Wales Borderers from the Reserve Brigade, 115th—came up to thicken the line. At about four, the attack was renewed, until at least two-thirds of the wood had been gained. The South Wales Borderers worked up the eastern side, pushing the defenders into the open, where they were shot down by British machine-guns in Caterpillar Wood and Marlborough Wood. About 50 yards from the northern end the khaki line was at last held up and remained there, crouching in shell-holes or behind broken trunks. The main resistance came from a trench outside the wood, and it was eventually determined to bombard it, for which purpose the troops were withdrawn some hundreds of yards. Late in the evening there was another gallant attempt to get the edge of the wood, but the trench was as venomous as ever, and the main German second line behind it was sweeping the underwood with bullets, so the advance was halted for the night.

During the night the 115th Brigade had come to the front, and in the morning of July 11 had relieved the 113th and 114th Brigades. The relief in a thick wood, swept by bullets, and upon a dark night in the close presence of a formidable enemy, was a most difficult operation. The morning was spent in reconnaissance, and it was only at 3. 15 P.M. that the advance could be made upon the main German defence, a trench just outside the north end of the wood. About 4 o’clock the Brigade swept on, and after a sharp bayonet fight gained the trench towards the north-east, but the Germans still held the centre and swept with their fire the portion in our possession. The 11th South Wales Borderers (2nd Gwents) held on splendidly, in spite of their heavy losses. The situation was now such, with only 300 yards to go to reach the German second line, that it was deemed well to relieve the Thirty-eighth Division by the Twenty-first Division, who had been selected for the coming battle. This change was carried out by the morning of July 12.

The action of the Thirty-eighth Division in capturing Mametz Wood had been a very fine one, and the fruit of their victory was not only an important advance, but 398 prisoners, one field gun, three heavy guns, a howitzer and a number of smaller pieces. It was the largest wood in the Somme district, and the importance attached to it by the Germans may be gathered from the fact that men of five different German regiments, the 3rd Lehr, 16th Bavarians, 77th, 83rd, and 122nd, were identified among our opponents. Among many instances of individual valour should be mentioned that of a colonel of the Divisional Staff, who twice, revolver in hand, led the troops on where there was some temporary check or confusion. It is impossible to imagine anything more difficult and involved than some of this fighting, for apart from the abattis and other natural impediments of a tangled wood, the place was a perfect rabbit-warren of trenches, and had occasional land mines in it, which were exploded—some of them prematurely, so that it was the retreating Germans who received the full force of the blast. Burning petrol was also used continually in the defence, and frequently proved to be a two-edged weapon. Some of the garrison stood to their work with extraordinary courage, and nothing but the most devoted valour upon the part of their assailants could have driven them out. “Every man of them was killed where he stood,” said a Welsh Fusilier, in of the describing the resistance of one group. “They refused offers of quarter right to the last, and died with cheers for the Kaiser or words of defiance on their lips. They were brave men, and we were very sorry indeed to have to kill them, for we could not but admire them for their courage.” Such words give honour both to victors and vanquished. The German losses were undoubtedly very heavy—probably not less than those of the Welsh Division.

Though the Welsh Division had overrun Mametz Wood from south to north, there was still one angle in the north-west which had lain out of their course, and had not been taken by them. This part of the wood was occupied upon the evening of July 11 by the 62nd Brigade of the Twenty-first Division, which had already performed such notable services upon the Somme. Eight field-guns were discovered in this part of the wood and were captured by the Brigade.

The situation had now greatly improved for the Seventeenth Division in front of Quadrangle Support, for not only was Mametz Wood mostly in the hands of the Welsh, but the Twenty-third Division on the left, who after their temporary check at Contalmaison had fallen back upon the line Peake Alley —Birch Tree Wood—Shelter Wood, now came forward again and occupied Bailiff Wood upon the north of Contalmaison. Under these circumstances, the 50th Brigade upon the right again attempted to get forward in order to keep level with the Welsh in the wood. Connection had not yet been made at that point, however, and the 7th East Yorks, who were the leading battalion, suffered heavy losses before being compelled to abandon the attempt.

Victory, however, was at last coming to reward the living and vindicate the dead. At four in the afternoon of July 10, the Twenty-third Division advanced from Bailiff Wood for its second assault upon Contalmaison. This time everything went to perfection, and the much-enduring infantry were able to take possession of the village, while a counter-attack by the third Reserve Division of the Prussian Guards came under concentrated artillery fire, and was completely disorganised and destroyed. It was the wounded of the Guard from this attack who were seen at Potsdam, and described by Mr. Curtin, the American journalist, in one of the most brilliant articles of the War. Carried into furniture vans, they were conveyed to their hospitals with every secrecy, in order to conceal from the populace the results of the encounter between the famous Corps and those men of the New Army who for more than a year had been the favourite butt of the Witz-Blätter of Berlin. Old Father Time has a humour of his own, and his laugh is usually the last. Besides the Guard the 70th Jaeger and the 110th, 114th, and 119th Regiments were included in this defeat.

The two bastions having fallen, the problem of the Quadrangle Support became a very different one, and the 51st Brigade, joining up with the right of the Twenty-third Division in the evening, was able to get hold of the left end of it. Even now, however, the Germans fought hard to the right, and both the 7th East Yorks and the 6th Dorsets had to push strongly before they could win through. They were encouraged in their efforts when, in the waning light, they were able to see small bodies of the enemy retiring in the distance out of the fringe of the wood. By ten o’clock that night the long task had been accomplished, and the dead might sleep in peace, for Quadrangle Support was in the hands of the Seventeenth Division. They were relieved by the Twenty-first Division upon July 11.

At or about the same time as the relief of the Seventeenth Division, the Twenty-third upon their left were also relieved, their line being taken over by the First Division. Since the capture of Contalmaison and the heavy repulse of the German Guard Division the British had made further progress, so that both Pearl Wood and Contalmaison Villa to the north of the village were firmly in their hands. The instructions to the First Division were to endeavour to improve this advantage, and an advance was at once made which, occurring as it did upon the night of July 15, may be best described under the heading which treats of the breaking of the second German line.

Having dealt with the operations upon the left and those in the centre of the intermediate German position, we will now turn to those upon the right, which are concerned with the Eighteenth and the Thirtieth Divisions, supported by the Ninth. After the fall of Montauban, these Divisions advanced, the one upon Caterpillar Wood, and the other to Bernafoy Wood, both of which were occupied. For the occupation of Bernafoy Wood the 27th Brigade of the Ninth Division had been put at the disposal of the commander of the Thirtieth, and this force occupied the position without much loss, but were exposed afterwards to a most deadly shell-fire, which caused heavy losses to the two front battalions—the 6th King’s Own Scottish Borderers and the the 6th Scots Rifles. The wood was held, however, together with three guns, which were found within it. On July 5 the Thirtieth Division handed over that line to the Ninth. On that date they sustained the heavy loss of Colonels Trotter and Smith—both killed by distant shell-fire.

The rest of the Thirtieth Division only lasted for a very few days, and upon July 7 they were facing the enemy position from Malzhorn Farm upon the right to Trones Wood upon the left, and were about to be initiated in that terrible wood fighting which cost us so dear. There is no fighting in the world which is more awesome to the mind and more exhausting to the body than such combats as these amid the ghostly atmosphere of ruined woods, with Death lurking in the shadows on every hand, and the thresh of the shells beating without cessation by night and by day. Trones, Mametz, High Wood, Delville —never has the quiet, steadfast courage of the British soldier been put to a more searching test than in those haunts of gloom and horror. In the case of Trones Wood some account must be given of the peculiar tactical difficulties of the situation, and then we shall turn to the sombre but glorious narrative of the successive attacks.

The tactical problem was a remarkable one. The wood was connected up on the German side by good lines of trenches with Malzhorn Farm on the south, with Guillemont on the east, and with Waterlot Farm on the north—each of these points being from 400 to 700 yards away. It was also commanded by a large number of heavy guns. The result was that if the British stormers held the wood in strength, they were shelled out with heavy losses. If, on the other hand, the wood were lightly held, then the German infantry pouring in from the east and north could drive them out. The British, on the other hand, had no trenches leading up to the wood, though in other respects the Germans found the same difficulties in holding the place that they did. It was a terrible contest in tenacity between the infantry of the two nations, and if in the end the British won it must at least be admitted that there was no evidence of any demoralisation among the Germans on account of the destruction of their main line. They fought well, were well led, and were admirably supported by their guns.

The first attack upon Trones Wood was carried out from the south upon July 8 by the 21st Brigade. There was no suspicion then of the strength of the German position, and the attack was repulsed within a couple of hours, the 2nd Yorks being the chief sufferers.

There was more success upon the right of the line where the French were attacking Malzhorn Farm. A company of the 2nd Wilts made their way successfully to help our Allies, and gained a lodgment in the German trenches which connect Malzhorn Farm with the south end of Trones Wood. With the aid of some of the 19th Manchesters this position was extended, and two German counter attacks were crushed by rifle- fire. The position in this southern trench was permanently held, and it acted like a self-registering gauge for the combat in Trones Wood, for when the British held the wood the whole Southern Trench was British, while a German success in the wood always led to a contraction in the holding of the trench.

At one o’clock upon July 8 the 21st Brigade renewed their attempt, attacking with the 2nd Wiltshires in the lead from the side of Bernafoy Wood. The advance was a fine one, but Colonel Gillson was badly wounded, and his successor in command. Captain Mumford, was killed. About three o’clock the 18th and 19th Manchesters came up in support. German bombers were driving down from the north, and the fighting was very severe. In the evening some of the Liverpools came up to strengthen the line, and it was determined to draw out the weakened 21st, and replace it by the 90th Brigade. At the same time a party of the 2nd Scots Fusiliers of this Brigade took over Malzhorn Trench, and rushed the farmhouse itself, capturing 67 prisoners. The whole of the trench was afterwards cleared up with two machine-guns and 100 more prisoners. It was a fine bit of work, worthy of that splendid battalion.

Upon July 9 at 6.40 A.M. began the third attack upon Trones Wood led by the 17th Manchesters. They took over the footing already held, and by eight o’clock they had extended it along the eastern edge, practically clearing the wood of German infantry. There followed, however, a terrific bombardment, which caused such losses that the 17th and their comrades of the 18th were ordered to fall back once more, with the result that the Scots Fusiliers had to give up the northern end of their Malzhorn Trench. An enemy counter-attack at 4:30 P.M. had no success. A fresh British attack (the fourth) was at once organised, and carried out by the 16th Manchesters, who at 6.40 P.M. got into the south end of the wood once more, finding a scattered fringe of their comrades who had held on there. Some South African Highlanders from the Ninth Division came up to help them during the night. This fine battalion lost many men, including their colonel, Jones, while supporting the attack from Bernafoy Wood. In the morning the position was better, but a gap had been left between the Manchesters in the wood and the Scots in the trench, through which the enemy made their way. After much confused fighting and very heavy shelling, the evening of July 10 found the wood once more with the Germans.

In the early morning of July 11 the only remaining British Brigade, the 89th, took up the running. At 3:50 the 2nd Bedfords advanced to the attack. Aided by the 19th King’s Liverpools, the wood was once again carried and cleared of the enemy, but once again a terrific shell-fall weakened the troops to a point where they could not resist a strong attack. The Bedfords fought magnificently, and had lost 50 per cent of their effectives before being compelled to withdraw their line. The south-east corner of the wood was carried by the swarming enemy, but the south-west corner was still in the hands of our utterly weary and yet tenacious infantry. At 9:30 the same evening the 17th King’s Liverpools pushed the Germans back once more, and consolidated the ground won at the southern end. So the matter stood when the exhausted division was withdrawn for a short rest, while the Eighteenth Division took up their difficult task. The Lancashire men had left it unfinished, but their conduct had been heroic, and they had left their successors that one corner of consolidated ground which was needed as a jumping-off place for a successful attack.

It was the 55th Brigade of the Eighteenth Division which first came up to take over the fighting line. A great responsibility was placed upon the general officer commanding, for the general attack upon the German line had been fixed for July 14, and it was impossible to proceed with it until the British held securely the covering line upon the flank. Both Trones Wood and the Malzhorn Trench were therefore of much more than local importance, so that when Haig found himself at so late a date as July 12 without command of this position, it was a very serious matter which might have far-reaching consequences. The orders now were that within a day, at all costs, Trones Wood must be in British hands, and to the 55th, strengthened by two battalions of the 54th Brigade, was given the desperate task. The situation was rendered more difficult by the urgency of the call, which gave the leaders no time in which to get acquainted with the ground.

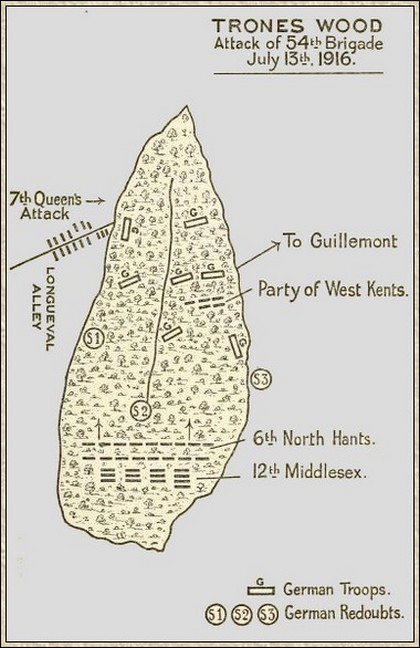

Trones Wood: Attack of 54th Brigade, July 13, 1916

The German defence had become a strong one. They had formed three strong points, marked S1, S2, and S3 in the Diagram, p. 141. These, together with several trenches, dotted here and there, broke up every attack, and when once order was broken it was almost impossible in the tangle and obscurity for the troops to preserve any cohesion or direction. Those troops which penetrated between the strong points found themselves with the enemy in their rear and were in a disorganised condition, which was only overcome by the individual bravery of the men, who refused to be appalled by the difficult situation in which they found themselves. The attack of the 55th Brigade was made from of the the sunken road immediately south of the wood, and it ran at once into so heavy a barrage that it lost heavily before it had reached even the edge of its objective. The 7th West Kents, who formed the attacking force, were not to be denied, however, and they pushed forward through a deepening gloom, for it was seven in the evening before the signal had been given. Whilst the Kents fought up from the south, the Queen’s Surreys attempted to wan a lodgment on the north-west where the Longueval Alley led up from Bernafoy Wood. They also suffered heavily from the barrage, and only a few brave men reached the top of the wood and held on there for some hours. The West Kents passed the line of strong points and then lost touch with each other, until they had resolved themselves into two or three separate groups holding together as best they could in the darkness with the enemy all round them, and with the communications cut behind them. The telephone wires had all been broken by the barrage, and the anxious commanders could only know that the attack had failed, that no word came back from the front, and that a British battalion had been swallowed up by the wood.

The orders were peremptory, however, that the position should be taken, and General Maxse, without hesitation, threw a second of his brigades into the dangerous venture. It was the 54th Brigade which moved to the attack. It was just past midnight when the soldiers went. forward. The actual assault was carried out from south to north, on the same line as the advance of the West Kents. The storming battalions were the 6th Northamptons and 12th Middlesex, the former to advance direct through the and the latter to clean up behind them and to form a defensive flank on the right.

The attack was a fine feat of arms. Though heavily hit by the barrage, the Northamptons, closely followed by two companies of the Middlesex, pushed their way into the wood and onwards. It was pitch dark, and the men were stumbling continually over the fallen trees and the numerous dead bodies which lay among the undergrowth. None the less, they kept touch, and plodded steadily onwards. The gallant Clark was shot, but another officer led the Northamptons against the central strong point, for it had been wisely determined to leave no enemy in the rear. Shortly after dawn on July 14 this point was carried, and the Northamptons were able to get forward. By 8 o’clock the wood was full of scattered groups of British infantry, but the situation was so confused that the colonel went forward and rallied them into a single line which formed across the wood. This line advanced until it came level with the strong point S 3, which was captured. A number of the enemy then streamed out of the eastern side of the wood, making for Guillemont. These men came under British machine-gun fire and lost heavily. The remaining strong point at S1 had been taken by a mixed group of Buffs and Middlesex about 9 A.M. These three strong points having been occupied, the whole wood was now swept clear and was permanently occupied, though still subjected to very heavy shell fire by the enemy. Thus, the right flank of the army was covered, and the important operations of July 14 were enabled to go forward without danger of the of molestation. Of the two gallant battalions who mainly achieved this important result, the losses of the Northamptons were about 300, and of the Middlesex about half that amount.

There was an epilogue which was as honourable to the troops concerned as the main attack had been. This concerns the fate of the men of West Kent, who, as will be remembered, had been cut off in the wood. The main body of these, under the regimental adjutant, together with a few men of the Queen’s, formed a small defensive position and held out in the hope of relief. They were about 200 all told, and their position seemed so hopeless that every excuse might have been found for surrender. They held out all night, however, and in the morning they were successfully relieved by the advance of the 54th Brigade. It is true that no severe attack was made upon them during the night, but their undaunted front may have had something to do with their immunity. Once, in the early dawn, a German officer actually came up to them under the impression that they were his own men—his last mistake upon earth. It is notable that the badges of six different German regiments were found in the wood, which seemed to indicate that it was held by picked men or volunteers from many units. “To the death!” was their password for the night, and to their honour be it said that they were mostly true to it. So also were the British stormers, of whom Sir Henry Rawlinson said: “The night attack on and final capture of Trones Wood were feats of arms which will rank high among the best achievements of the British Army.”

An account of this fortnight of desperate and almost continuous fighting is necessarily concerned chiefly with the deeds of the infantry, but it may fitly end with a word as to the grand work of the artillery, without whom in modern warfare all the valour and devotion of the foot-soldier are but a useless self-sacrifice. Nothing could exceed the endurance and the technical efficiency of the gunners. No finer tribute could be paid them than that published at the time from one of their own officers, which speaks with heart and with knowledge: “They worked their guns with great accuracy and effect without a moment’s cessation by day or by night for ten days, and I don’t believe any artillery have ever had a higher or a longer test or have done it more splendidly. And these gunners, when the order came that we must pull out and go with the infantry—do you think they were glad or willing? Devil a bit! They were sick as muck and only desired to stay on and continue killing Boches. And these men a year ago not even soldiers—much less gunners! Isn’t it magnificent—and is it not enough to make the commander of such men uplifted?” No cold and measured judgment of the historian can ever convey their greatness with the conviction produced by one who stood by them in the thick of the battle and rejoiced in the manhood of those whom he had himself trained and led.

The Second German Line, Bazentins, Delville Wood, etc.