VII. The Battle of the Somme

July 14 to July 31

Gradual advance of First Division—Hard fighting of Thirty-third Division at High Wood—The South Africans in Delville Wood—The great German counter-attack—Splendid work of 26th Brigade—Capture of Delville Wood by 98th Brigade—Indecisive fighting on the Guillemont front

The central fact of the situation after the battle of Bazentin was that although the second German line had been broken, the gap made was little more than three miles wide, and must be greatly extended upon of the either flank before a general advance upon the third line could take place. This meant that the left wing must push out in the Pozières direction, and that the right wing must get Ginchy and Guillemont. For the time the central British position was not an advantageous one, as it formed a long salient bending from High Wood through Delville Wood to Guillemont, so placed that it was open to direct observation all along, and exposed to converging fire which could be directed with all the more accuracy as it was upon points so well known to the Germans, into which the guns, communications, and reserves were now crammed. Sir Douglas Haig’s great difficulties were increased by a long spell of wet and cloudy weather, which neutralised his advantages in the air. Everything was against the British General except the excellence of his artillery and the spirit of his troops.

The French upon the right, whose tally of guns and prisoners were up to date higher than those of the British, had an equally hard front to attack, including the four strong villages of Maurepas, Le Forest, Raucourt, and Fregicourt, with many woods and systems of trenches. Their whole work in the battle had been worthy of their military history, and could not be surpassed, either in the dispositions of General Foch or in the valour of his men. Neither their infantry nor ours had ever relinquished one square yard that they had wrenched from the tight grip of the invader.

In each area of the battle of July 14 some pressing task was left to be accomplished, and the fighting was very severe at certain points for some days later. We shall first turn to the north of the line, where new divisions had come into action. One of these already mentioned was the First Division. It was indeed pleasing and reassuring to observe how many of the new divisional generals were men whose names recalled good service as regimental officers. Many who now wore the crossed swords upon their shoulders had been battalion commanders in 1914. It is indeed well with an army when neither seniority nor interest but good hard service upon the field of battle puts officers in charge of the lives of men.

The First Division had taken the place of the Twenty-third after the fall of Contalmaison, and had pushed its way up until it was level with the line of their comrades on the right, whence in the manner described at the end of the last chapter they drove their line forward upon July 15. On the 20th they received a rebuff, however, the 1st Northants being held up by a very formidable German trench called Munster Alley. The ground already gained was consolidated, however, and the division lay with its left touching the Australians on the right of Gough’s army, and its right connected with the Thirty-third Division, whose doings at High Wood will presently be considered. For the purpose of continuity of narrative it will be best to continue with a short summary of the doings of the First Division upon the left wing of the advance, their general task being to hold that flank against German counter-attacks, and to push forward wherever possible. It was continuous hard work which, like so many of these operations, could gain little credit, since there was no fixed point but only a maze of trenches in front of them. The storming of a nameless ditch may well call for as high military virtue as the taking of a historic village, and yet it seems a slighter thing in the lines of a bulletin. Munster Alley and the great Switch Line faced the First Division, two most formidable obstacles. On July 23, in the early morning, the 2nd Brigade of the First Division attacked the Switch Line, in conjunction with the Australians, on the left, and the Nineteenth Division to the right. The attack was held up, Colonel Bircham of the 2nd Rifles and many officers and men being killed. Colonel Bircham was a particularly gallant officer, who exposed himself fearlessly upon every occasion, and it is on record that when remonstrated with by his adjutant for his reckless disregard of danger, he answered, “You know as well as I do where a colonel of the 60th ought to be.” Such lives are an example and such deaths an inspiration. Altogether the 2nd Rifles lost about 250 men in this night attack, and the other first line battalions—the 2nd Sussex, 10th Gloucesters, and 1st Cameron Highlanders—were all hard hit. The failure seems to have been partly due to misdirection in the dark.

Upon July 25 the 1st South Wales Borderers of the 3rd Brigade attacked Munster Alley, but were again unable to get forward on account of the machine-guns. Nothing daunted, the 2nd Welsh had another fling at Munster Alley next day, and actually took it, but had not weight enough to consolidate and to hold it. On the other hand, the British line was held inviolate, and a strong German attack upon July 25 towards Pozières was repulsed with loss.

The Twenty-third Division relieved the First and were in turn relieved by the Fifteenth in this sector, which faced the Switch Trench and Martinpuich. The Switch Line was exposed to a very heavy fire for several days, at the end of which it was attacked by this famous division, the same in number at least as that which had left nearly two-thirds of its rank and file upon the bloody slopes of Hill 70. On August 12 the advance was carried out with great dash: the 45th Brigade upon the left and the 46th upon the right. The attack was only partially successful, and the 46th Brigade was held up through the fact that the Germans had themselves been in the act of attack, so that the trenches were very strongly held. The operations continued, however, and the initial gains were enlarged, until upon August 20 the whole Switch Line fell and was permanently consolidated.

Leaving this left sector we must turn to the Thirty-third Division on its right, two battalions of which had got forward on July 15, as far as the line of the road connecting High Wood with Little Bazentin. The right flank of the Highland Light Infantry had been held up by fire from this wood, and in the evening the 91st Brigade of the Seventh Division had evacuated the southern edge of the wood in order to allow of bombardment. That was the position on the night of July 15.

The line of the road was held all night, and early next morning the advance was ordered upon the German Switch Trench in front. It was hoped that the wood had been cleared during the night, but in the morning the Highlanders found themselves still galled by the continual fire upon their right. It was clear that the attack could not go forward with such an impediment upon the flank—one more instance of a brigade being held up by a handful of concealed men. It was hoped that the enemy had been silenced, and the attack was made, but no sooner had it developed than a murderous fire burst from the wood, making it impossible for the Highlanders to get along farther than the road. The 1st Queen’s, however, being farther from the wood were able to get on to the Switch Trench, but found it heavily wired and stiff with men. Such a battalion does not take “No” easily, and their colonel, with a large proportion of their officers and men, was stretched in front of the fatal wire before it became evident that further perseverance would mean destruction. The 16th Rifles and half the 2nd Worcesters, the remaining battalions of the 100th Brigade, were brought up, but not further advance was possible until the wire could be cut by the guns. About four in the afternoon of July 16 the remains of the brigade were back in the road from which they had started. The attack had failed, partly from the enfilade fire of High Wood, partly from the impassable wire.

The 98th Brigade was on the left of the 100th, filling up the gap to Bazentin village. They had extended their right in order to help their sorely tried comrades, and they had themselves advanced upon the line of the Switch Trench—the 1st Middlesex leading, with the 4th Suffolk in support. The 2nd Argyll and Sutherlands with the 4th King’s Liverpool were in reserve. They got well forward, but ceased their advance when it was found that no progress could be made upon the right. Thus, for the time, the division was brought to a stand. That night the 19th Brigade relieved the 100th, which had been very hard hit in this action. After the change the 1st Scottish Rifles and the 20th Royal Fusiliers formed the front line of the 19th Brigade, the Rifles in touch with the 22nd Brigade of the 7th upon their right, while the Fusiliers were in touch with the 98th Brigade upon their left.

The general situation did not admit of an immediate attack, and the Germans took advantage of the pause to strengthen and slightly to advance their position. On July 17 the hard-worked Twenty-first Division upon the left was drawn out, and both the Thirty-third and Seventh had to extend their fronts. On the other hand, the First Division came in upon the left and occupied a portion of the Bazentin-le-Petit Wood. The position at that time was roughly that the Seventh Division covered the front from High Wood to Bazentin Grand, the Thirty-third Division from Bazentin Grand to Bazentin Petit, the First was from their left to Pozières.

Upon July 18 there was a very heavy German attack upon Delville Wood, which is treated elsewhere. This was accompanied by a severe barrage fire upon the Bazentins and upon Mametz Wood, which continued all day. That night the Nineteenth Division came into line, taking over Bazentin Petit, both village and wood. The Thirty-third Division moved to the right and took some pressure off the Seventh, which had done such long and arduous service. These incessant changes may seem wearisome to the reader, but without a careful record of them the operations would become chaos to any one who endeavoured to follow them in detail. It is to be emphasised that though divisions continually changed, the corps to which they temporarily belonged did not change, or only at long intervals, so that when you are within its area you can always rely upon it that in this particular case Horne of the Fifteenth Corps is the actual brain which has the immediate control of the battle.

As the pressure upon Congreve’s Thirteenth Corps on the right at Delville Wood and elsewhere was considerable, it was now deemed advisable to attack strongly by the Fifteenth Corps. The units for attack were the Thirty-third Division upon the left, and the depleted Seventh upon their right. There was to be no attack upon the left of the Thirty-third Division, but the 56th Brigade of the Nineteenth Division was handed over to the 33rd Division to strengthen the force. The objectives to be attacked were once again High Wood (Bois des Foureaux), Switch Trench, and the connecting trench between them. The Seventh Division attacked east of the wood on the line between it and Delville Wood.

The assault upon High Wood was assigned to the 19th Brigade. The 2nd Worcesters of the 98th Brigade were pushed out so as to cover the left flank of the assaulting column. At 2 A.M. of July 20 the two advance battalions of stormers, the 5th Scottish Rifles on the right, the 1st Scottish Rifles upon the left, were formed up in open ground outside the British wire. Preceded by scouts, they went silently forward through the gloom until they approached the south-western edge of the wood. A terrific bombardment was going on, and even those stout northern hearts might have quailed at the unknown dangers of that darksome wood, lit from moment to moment by the red glare of the shells. As the barrage lifted, the wave of infantry rushed forward, the 5th Scottish Rifles making for the eastern edge, while the 1st Regular Battalion pushed on in the endeavour to win through and secure the northern edge.

It was speedily found that the tenacious enemy had by no means loosened his grip of the wood. A portion of the Switch Trench runs through it, and this was strongly held, a line of spurting flames amid the shadow of the shattered trees. Machine-guns and wire were everywhere. None the less, the dour Scots stuck to their point, though the wood was littered with their dead. Both to east and to north they slowly pushed their way onwards to their objectives. It was a contest of iron wills, and every yard won was paid for in blood. By 9 o’clock the whole of the southern half of the wood had been cleared, the leading troops being helped by the 20th Fusiliers, who followed behind them, clearing up the lurking Germans. At that hour the northern end of the wood was still strongly held by the enemy, while the stormers had become much disorganised through loss of officers and through the utter confusion and disintegration which a night attack through a wood must necessarily entail.

The remaining battalion of the 19th Brigade, the 2nd Welsh Fusiliers, was, at this critical moment, thrown into the fight. A heavy barrage was falling, and considerable losses were met with before the wood was entered; but the Fusiliers went forward with splendid steadiness and dash, their colonel taking entire local command. In the early afternoon, having got abreast of the exhausted Scottish Rifles, who had been under the hottest fire for nearly twelve hours, the Welsh attacked the north end of the wood, their advance being preceded by a continuous fire from our Stokes mortars, that portable heavy artillery which has served us so well. The enemy was still unabashed, but the advance was irresistible, and by 7 P.M. the British were for a time in possession of the whole of the blood-sodden plantation. It was a splendid passage of arms, in which every devilry which an obstinate and ingenious defence could command was overcome by the inexorable British infantry. The grim pertinacity of the Scots who stood that long night of terror, and the dash of the Welsh who carried on the wave when it was at the ebb, were equally fine; and solid, too, was the work of the public school lads of the 20th Fusiliers, who gleaned behind the line. So terrific was the shell-fire of the disappointed Germans upon the north end of the wood, that it was impossible to hold it; but the southern part was consolidated by the 18th Middlesex Pioneer Battalion and by the 11th Company Royal Engineers.

Whilst the Thirty-third Division stormed High Wood, their neighbours upon the right, the Seventh Division, depleted by heavy losses but still full of spirit, had been given the arduous and important task of capturing the roads running south-west from High Wood to Longueval. The assaulting battalions, the 2nd Gordons on the left and the 8th Devons on the right, Aberdeen and Plymouth in one battle line, advanced and took their first objective through a heavy barrage. Advancing farther, they attempted to dig in, but they had got ahead of the attack upon the left, and all the machine-guns both of Switch Trench and of High Wood were available to take them in flank and rear. It was a deadly business—so deadly that out of the two leading platoons of Gordons only one wounded officer and five men ever got back. Finally, the whole line had to crawl back in small groups to the first objective, which was being consolidated. That evening, the Fifth Division took over the lines of the Seventh, who were at last drawn out for a rest. The relief was marked by one serious mishap, as Colonel Gordon, commanding a battalion of his clansmen, was killed by a German shell.

It has been stated that the 56th Brigade of the Nineteenth Division had been placed under the orders of the Thirty-third Division during these operations. Its role was to cover the left flank of the attack and to keep the Germans busy in the Switch Line position. With this object the 56th Brigade, with the 57th Brigade upon its left, advanced its front line upon the night of July 22, a movement in which the 7th South Lancashires upon The the right of the 56th Brigade were in close touch with the 2nd Worcesters upon the left of the 100th Brigade. Going forward in the darkness with German trenches in front of them and a raking fire from High Wood beating upon their flank the Lancashire men lost heavily and were unable to gain a footing in the enemy’s position. This brigade had already suffered heavily from shell-fire in its advance to the front trenches. Two deaths which occurred during this short episode may be cited as examples of the stuff which went to the building up of Britain’s new armies. Under the shell-fire fell brave old Lieutenant Webb, a subaltern in the field, a Master of Foxhounds at home, father of another dead subaltern, and 64 years old. In the night operation, gallantly leading his company, and showing his comrades in the dark how to keep direction by astronomy, fell Captain Gerard Garvin, student, poet, essayist, and soldier, just 20 years of age. A book might be written which would be a national inspiration dealing with the lives of those glorious youths who united all that is beautiful in the mind with all that is virile in the body, giving it unreservedly in their country’s cause. They are lives which are more reminiscent of Sydney, Spencer, and the finer of the Elizabethans than anything we could have hoped to evolve in these later days. Raymond Asquith, Rupert Brooke, Charles Lister, Gerard Garvin, Julian Grenfell, Donald Hankey, Francis Ledwidge, Neil Primrose, these are some at least of this finest flower of British culture and valour, men who sacrificed to the need of the present their inheritance as the natural leaders of the future.

Though the Nineteenth Division was able to make no progress upon the night of July 22, upon the next night one of their brigades, the 58th, reinforced by two other battalions, made a strong movement forward, capturing the strong point upon the edge of the wood which had wrought the mischief the night before, and also through the fine work of the 10th Warwicks and 7th King’s Own carrying the whole British line permanently forward upon the right, though they could make no headway upon the left. Some conception of the services of the Nineteenth Division may be gathered from the fact that during the month of July it had lost 6500 casualties.

The Thirty-third Division was given a well deserved rest after their fine exploit in High Wood. During seven days’ fighting it had lost heavily in officers and men. Of individual battalions the heaviest sufferers had been the two Scottish Rifle battalions, the 20th Royal Fusiliers, the 1st Queen’s Surrey, 9th Highland Light Infantry, and very specially the 16th King’s Royal Rifles.

Whilst this very severe fighting had been going on upon the left centre of the British advance, an even more arduous struggle had engaged our troops upon the right, where the Germans had a considerable advantage, since the whole of Delville Wood and Longueval formed the apex of a salient which jutted out into their position, and was open to a converging artillery fire from several directions. This terrible fight, which reduced the Ninth Scottish Division to about the strength of a brigade, and which caused heavy losses also to the Third Division, who struck in from the left flank in order to help their comrades, was carried on from the time when the Highland Brigade captured the greater part of the village of Longueval, as already described in the general attack upon July 14.

On the morning after the village was taken, the South African Brigade had been ordered to attack Delville Wood. This fine brigade, under a South African veteran, was composed of four battalions, the first representing the Cape Colony, the second Natal and the Orange River, the third the Transvaal, and the fourth the South African Scotsmen. If South Africa could only give battalions where others gave brigades or divisions, it is to be remembered that she had campaigns upon her own frontiers in which her manhood was deeply engaged. The European contingent was mostly British, but it contained an appreciable proportion of Boers, who fought with all the stubborn gallantry which we have good reason to associate with the name. Apart from the infantry, it should be mentioned that South Africa had sent six heavy batteries, a fine hospital, and many labour detachments and special services, including a signalling company which had the reputation of being the very best in the army, every man having been a civilian expert.

The South Africans advanced at dawn, and their broad line of skirmishers pushed its way rapidly through the wood, sweeping all opposition before it. By noon they occupied the whole tract with the exception of the north-west corner. This was the corner which abutted upon the houses north of Longueval, and the murderous machine-guns in these buildings held the Africans off. By night, the whole perimeter of the wood had been occupied, and the brigade was stretched round the edges of the trees and undergrowth. Already they were suffering heavily, not only from the Longueval guns upon their left, but from the heavy German artillery which had their range to a nicety and against which there was no defence. With patient valour they held their line, and endured the long horror of the shell-fall during the night.

Whilst the South Africans were occupying Delville Wood, the 27th Brigade had a task which was as arduous, and met in as heroic a mood, as that of their comrades on the day before. Their attack was upon the orchards and houses to the north and east of Longueval, which had been organised into formidable strong points and garrisoned by desperate men. These strong points were especially dangerous on account of the support which they could give to a counter-attack, and it was thus that they did us great mischief. The Scottish Borderers, Scots Fusiliers, and Royal Scots worked slowly forward during the day, at considerable cost to themselves. Every house was a fortress mutually supporting every other one, and each had to be taken by assault. “I saw one party of half-a-dozen Royal Scots rush headlong into a house with a yell, though there were Germans at every window. Three minutes later one of the six came out again, but no more shots ever came from that house.” Such episodes, with ever-varying results, made up that long day of desperate fighting, which was rendered more difficult by the heavy German bombardment. The enemy appeared to be resigned to the loss of the Bazentins, but all their energy and guns were concentrated upon the reconquest of Longueval and Delville Wood. Through the whole of the 16th the shelling was terribly severe, the missiles pitching from three separate directions into the projecting salient. Furious assaults and heavy shell-falls alternated for several days, while clouds of bombers faced each other in a deadly and never-ending pelting match. It was observed as typical of the methods of each nation that while the Germans all threw together with mechanical and effective precision, the British opened out and fought as each man judged best. This fighting in the wood was very desperate and swayed back and forwards.

“It was desperate hand-to-hand work. The enemy had no thought of giving in. Each man took advantage of the protection offered by the trees, and fought until he was knocked out. The wood seemed swarming with demons, who fought us tooth and nail.” The British and Africans were driven deeper into the wood. Then again they would win their way forwards until they could see the open country through the broken trunks of the lacerated trees. Then the fulness of their tide would be reached, no fresh wave would come to carry them forwards, and slowly the ebb drew them back once more into the village and the forest. In this mixed fighting the Transvaal battalion took 3 officers and 130 men prisoners, but their losses, and those of the other African units, were very heavy. The senior officer in the firing line behaved with great gallantry, rallying his ever-dwindling forces again and again. A joint attack on the evening of July 16 by the Cape men, the South African Scots, and the 11th Royal Scots upon the north-west of the wood and the north of the village was held up by wire and machine-guns, but the German counter-attacks had no better fate. During the whole of the 17th the situation remained unchanged, but the strain upon the men was very severe, and they were faced by fresh divisions coming up from Bapaume. The Brigadier himself made his way into the wood, and reported to the Divisional Commander the extremely critical state of affairs.

On the morning of July 18 the Third Division were able to give some very valuable help to the hard-pressed Ninth. At the break of day the 1st Gordons, supported by the 8th King’s Liverpools, both from the 76th Brigade, made a sudden and furious attack upon those German strong points to the north of the village which were an ever-present source of loss and of danger. “Now and again,” says a remarkable anonymous account of the incident, “during a lull in the roar of battle, you could hear a strong Northern voice call out: ‘On, Gor-r-r-dons, on!’ thrilling out the r’s as only Scotsmen can. The men seldom answered save by increasing their speed towards the goal. Occasionally some of them called out the battle-cry heard so often from the throats of the Gordons: ‘Scotland for ever!’… They were out of sight over the parapet for a long time, but we could hear at intervals that cry of ‘On, Gor-r-r-dons, on!’ varied with yells of ‘Scotland for ever!’ and the strains of the pipes. Then we saw Highlanders reappear over the parapet. With them were groups of German prisoners.”

The assault won a great deal of ground down the north-west edge of Delville Wood and in the north of the village; but there were heavy losses, and two of the strong points were still intact. All day the bombardment was continuous and deadly, until 4:30 in the afternoon, when a great German infantry attack came sweeping from the east, driving down through the wood and pushing before it with an irresistible momentum the scattered bodies of Scottish and African infantry, worn out by losses and fatigue. For a time it submerged both wood and village, and the foremost grey waves emerged even to the west of the village, where they were beaten down by the Lewis guns of the defenders. The southern edge of the wood was still held by the British, however, and here the gallant 26th Brigade threw itself desperately upon the victorious enemy, and stormed forward with all the impetuosity of their original attack. The Germans were first checked and then thrown back, and the south end of the wood remained in British hands. A finer or more successful local counter-attack has seldom been delivered, and it was by a brigade which had already endured losses which made it more fit for a rest-camp than for a battle line. After this second exploit the four splendid battalions were but remnants, the Black Watch having lost very heavily, while the Argylls, the Seaforths, and the Camerons were in no better case. Truly it can never be said that the grand records of the historic regular regiments have had anything but renewed lustre from the deeds of those civilian soldiers who, for a time, were privileged to bear their names.

Whilst this severe battle had been in progress, the losses of the South Africans in Delville Wood had been terrible, and they had fought with the energy of desperate men for every yard of ground. Stands were made in the successive rides of the wood by the colonel and his men. During the whole of the 19th these fine soldiers held on against heavy pressure.

The colonel was the only officer of his regiment to return. Even the Newfoundlanders had hardly a more bloody baptism of fire than the South Africans, or emerged from it with more glory.

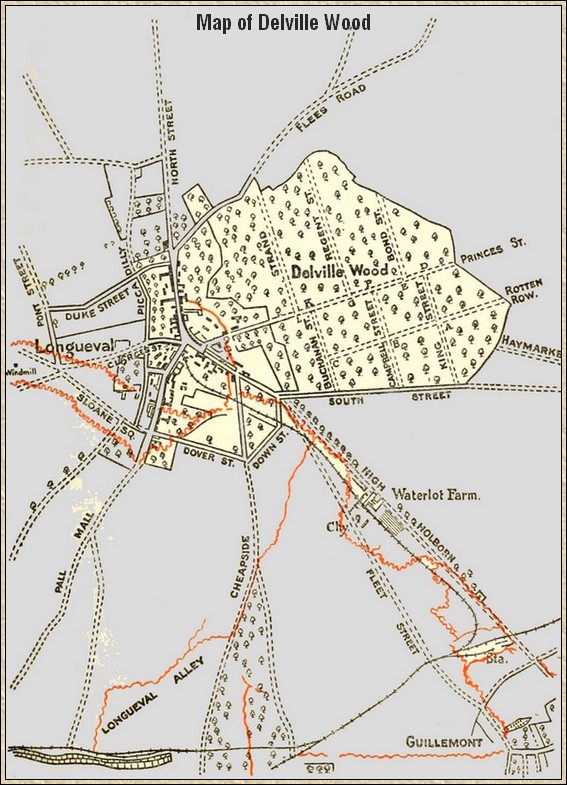

The situation now was that the south of the wood was held by the British, but the north, including the greater part of the village, was still held by the Germans. The worn-out Ninth Division, still full of spirit, but lacking sadly in numbers, was brought out of line upon July 19, and the Eighteenth English Division, fresh from its own great ordeal in Trones Wood, came forward to take its place. At seven in the morning of the 19th the 53rd Brigade attacked from the south, the situation being so pressing that there was no time for artillery preparation. The infantry went forward without it, and no higher ordeal could be demanded of them. It was evident that there was great danger of the strong German column breaking through to westward and so outflanking the whole British line. Only a British attack from north and from south could prevent its progress, so that the Third Division were called upon for the one, and the Eighteenth for the other. This wood of infamous memory is cut in two by one broad ride, named Princes Street, dividing it into two halves, north and south (vide p. 181). The southern half was now attacked by the 8th Norfolks, who worked their way steadily forward in a long fringe of bombers and riflemen. The Brigade-Major, Markes, and many officers and men fell in the advance. After a pause, with the help of their Lewis guns, the Norfolks pushed forward again, and by 2 o’clock had made their way up to Princes Street along most of the line, pushing the enemy down into the south-eastern corner. The remaining battalions of the brigade, the 10th Essex on the right and the 6th Berkshires on the left, tried to fight their way through the northern portion, while the 8th Suffolk attacked the village. Half of the of the village up to the cross-roads in the centre was taken by the Suffolk, but their comrades on the right were held up by the heavy machine-gun fire, and at 5 P.M. were compelled to dig themselves in. They maintained their new positions, under a terrific shell-fire, for three weary and tragic days, at the end of which they were relieved by the 4th Royal Fusiliers, a veteran battalion which had fired some of the first shots of the War.

These Fusiliers belonged to the Third Division which had, as already said, been attacking from the north side of the wood, while the Eighteenth were on the south side. On July 19 this attack had been developed by the 2nd Suffolk and the 10th Welsh Fusiliers, the two remaining battalions of the 76th Brigade. The advance was made at early dawn, and the Welsh Fusiliers were at once attacked by German infantry, whom they repulsed. The attack was unfortunate from the start, and half of the Suffolks who penetrated the village were never able to extricate themselves again. The Welsh Fusiliers carried on, but its wing was now in the air, and the machine-guns were very deadly. The advance was held up and had to be withdrawn. In this affair fell one of the most promising of the younger officers of the British army, a man who would have attained the very highest had he lived, Brigade-Major Congreve, of the 76th Brigade, whose father commanded the adjacent Thirteenth Corps. His death arose from one of his many acts of rash and yet purposeful valour, for he pushed forward alone to find out what had become of the missing Suffolks, and so met his end from some lurking sniper.

On July 20 matters had come to a temporary equilibrium in Delville Wood, where amid the litter of corpses which were strewn from end to end of that dreadful grove, lines of British and German infantry held each other in check, neither able to advance, because to do so was to come under the murderous fire of the other. The Third Division, worn as it was, was still hard at work, for to the south-west of Longueval a long line of hostile trenches connected up with Guillemont, the fortified farm of Waterlot in the middle of them. It was to these lines that these battle-weary men were now turned. An attack was pending upon Guillemont by the Thirtieth Division, and the object of the Third Division was to cut the trench line to the east of the village, and so help the attack. The advance was carried out with great spirit upon July 22 by the 2nd Royal Scots, and though they were unable to attain their full objective, they seized and consolidated a post midway between Waterlot Farm and the railway, driving back a German battalion which endeavoured to thrust them out. On July 23 Guillemont was attacked by the 21st Brigade of the Thirtieth Division. The right of the attack consisting of the 19th Manchesters got into the village, but few got out again; and the left made no progress, the 2nd Yorkshires losing direction to the east and sweeping in upon the ground already held by the 2nd Royal Scots and other battalions of the 8th Brigade. The resistance shown by Guillemont proved that the siege of that village would be a serious operation and that it was not to be carried by the coup-de-main of a tired division, however valiantly urged. The successive attempts to occupy it, culminating in complete success, will be recorded at a later stage.

On the same date, July 23, another attempt was made by mixed battalions of the Third Division upon Longueval. This was carried out with the co-operation of the 95th Brigade, Fifth Division, upon the left. The attack on the village itself from the south was held up, and the battalions engaged, including the 1st Northumberland Fusiliers, 12th West Yorkshires, and 13th King’s Liverpools, all endured considerable losses. Two battalions of the Thirty-fifth Division (Bantams), the 17th Royal Scots and 17th West Yorks, took part in this attack. There had been some movement all along the line during that day from High Wood in the north-east to Guillemont in the south-west; but nowhere was there any substantial progress. It was clear that the enemy was holding hard to his present line, and that very careful observation and renewed bombardment would be required before the infantry could be expected to move him. Thus, the advance of July 14, brilliant as it had been, had given less durable results than had been hoped, for no further ground had been gained in a week’s fighting, while Longueval, which had been ours, had for a time passed back to the enemy. No one, however, who had studied General Haig’s methods during the 1914 fighting at Ypres could, for a moment, believe that he would be balked of his aims, and the sequel was to show that he had lost none of the audacious tenacity which he had shown on those fateful days, nor had his well-tried instrument of war lost its power of fighting its way through a difficult position. The struggle at Longueval had been a desperate one, and the German return upon July 18 was undoubtedly the most severe reaction encountered by us during the whole of the Somme fighting; and yet after the fluctuations which have been described it finished with the position entirely in the hands of the British. On the days which followed the attack of July 23 the Thirteenth Brigade of the Fifth Division pushed its way gradually through the north end of the village, the 1st Norfolks bearing the brunt of the fighting. They were relieved on the 27th by the 95th Brigade, who took the final posts on the north and east of the houses, the 1st East Surreys holding the northern front. The 12th Gloucesters particularly distinguished themselves on this occasion, holding on to three outlying captured posts under a very heavy fire. The three isolated platoons maintained themselves with great constancy, and were all retrieved, though two out of three officers and the greater part of the men were casualties. This battalion lost 320 men in these operations, which were made more costly and difficult by the fact that Longueval was so exaggerated a salient that it might more properly be called a corner, the Germans directing their very accurate fire from the intact tower of Ginchy Church.

The Second Division had now been brought down to the Somme battle-front, and upon July 26 they took over from the Third Division in the area of Delville Wood. So complicated was the position at the point occupied, that one officer has described his company as being under fire from the north, south, east, and west, the latter being presumably due to the fact that the distant fire of the British heavies fell occasionally among the front line infantry. At seven in the morning of July 27 the 99th Brigade, now attached to the Second Division, was ordered to improve our position in the wood, and made a determined advance with the 1st Rifles upon the right, and the 23rd Fusiliers upon the left, the 1st Berkshires and 22nd Royal Fusiliers being in support. Moving forward behind a strong barrage, the two battalions were able with moderate loss to force their way up to the line of Princes Street, and to make good this advanced position. A trench full of dead or wounded Germans with two splintered machine-guns showed that the artillery had found its mark, and many more were shot down as they retired to their further trenches. The 1st Berkshires held a defensive flank upon the right, but German bombers swarmed in between them and the Rifles, developing a dangerous counter-attack, which was finally beaten off after a sharp fight, in which Captain Howell of the latter battalion was mortally wounded after organising a splendid defence, in which he was greatly helped by a sergeant. At 11 o’clock the left flank of the advance was also very heavily attacked at short range, and the two companies of the Rifles on that side were in sore straits until reinforced by bombers from the 23rd Fusiliers, and also by the whole of the 22nd Fusiliers. The German barrage fell thickly behind the British advance, and it was a difficult and costly matter to send forward the necessary supports, but before evening part of the 17th Fusiliers and of the 17th Middlesex from the 5th Brigade had pushed forward and relieved the exhausted front line. It was a most notable advance and a heroic subsequent defence, with some of the stiffest fighting that even Delville Wood had ever witnessed. The East Anglian Field Company Royal Engineers consolidated the line taken. The 1st Rifles, upon whom the greater part of the pressure had fallen, lost 14 officers, including their excellent adjutant, Captain Brocklehurst, and more than 300 men. The immediate conduct of the local operations depended upon the colonel of this battalion. The great result of the fight was that Delville Wood was now in British hands, from which it never again reverted. It is a name which will ever remain as a symbol of tragic glory in the records of the Ninth, the Third, the Eighteenth, and finally of the Second Divisions. Nowhere in all this desperate war did the British bulldog and the German wolf-hound meet in a more prolonged and fearful grapple. It should not be forgotten in our military annals that though the 99th Brigade actually captured the wood, their work would have been impossible had it not been for the fine advance of the 95th Brigade of the Fifth Division already recorded upon their Longueval flank.

Map of Delville Wood

We shall now turn our attention to what had been going on in the extreme right-hand part of the line, where in conjunction with the French three of our divisions, the 55th Lancashire Territorials, the 35th Bantams, and the hard-worked 30th, had been attacking with no great success the strong German line which lay in front of us after the capture of Trones Wood. The centre of this defence was the village of Guillemont, which, as already mentioned, had been unsuccessfully attacked by the 21st Brigade upon July 23. About this date the Thirty-sixth Bantam Division had a repulse at the Malzhorn Farm to the south of Guillemont, both the 104th and 105th Brigades being hard hit, and many of the brave little men being left in front of the German machine-guns.

A week later a much more elaborate attack was made upon it by the rest of the Thirtieth Division, strengthened by one brigade (the 106th) of the Thirty-fifth Division. This attack was carried out in cooperation with an advance of the Second Division upon Guillemont Station to the left of the village, and an advance of the French upon the right at Falfemont and Malzhorn.

The frontal advance upon Guillemont from the Trones Wood direction appears to have been about as difficult an operation as could be conceived in modern warfare. Everything helped the defence and nothing the attack. The approach was a glacis 700 yards in width, which was absolutely commanded by the guns in the village, and also by those placed obliquely to north and south. There was no cover of any kind. Prudence would no doubt have suggested that we should make good in the north at Longueval and thus outflank the whole German line of defence. It was essential, however, to fit our plans in with those of the French, and it was understood that those were such as to demand a very special, and if needs be, a self-immolating effort upon the right of the line.

The attack had been arranged for the morning of July 30, and it was carried out in spite of the fact that during the first few hours the fog was so dense that it was hard to see more than a few yards. This made the keeping of direction across so broad a space as 700 yards very difficult; while on the right, where the advance was for more than a mile and had to be coordinated with the troops of our Allies, it was so complex a matter that there was considerable danger at one time that the fight in this quarter would resolve itself into a duel between the right of the British Thirtieth and the left of the French Thirty-ninth Division.

The 89th Brigade advanced upon the right and the 90th upon the left, the latter being directed straight for the village. The two leading battalions, the 2nd Scots Fusiliers and the 18th Manchesters, reached it and established themselves firmly in its western suburbs; but the German barrage fell so thickly behind them that neither help nor munitions could reach them. Lieutenant Murray, who was sent back to report their critical situation, found Germans wandering about behind the line, and was compelled to shoot several in making his way through. He carried the news that the attack of the Second Division upon the station had apparently failed, that the machine-gun fire from the north was deadly, and that both battalions were in peril. The Scots had captured 50 and the Manchesters 100 prisoners, but they were penned in and unable to get on. Two companies of the 17th Manchesters made their way with heavy loss through the fatal barrage, but failed to alleviate the situation. It would appear that in the fog the Scots were entirely surrounded, and that they fought, as is their wont, while a cartridge lasted. Their last message was, that their ranks and munition supply were both thin, their front line broken, the shelling hard, and the situation critical. None of these men ever returned, and the only survivors of this battalion of splendid memories were the wounded in No Man’s Land and the Headquarter Staff. It was the second time that the 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers had fought to the last man in this war. Of the 18th Manchesters few returned, and two companies of the 16th Manchesters were not more fortunate. They got into the village on the extreme north, and found themselves in touch with the 17th Royal Fusiliers of the Second Division; but neither battalion could make good its position. It was one of the tragic episodes of the great Somme battle.

The 89th Brigade upon their right had troubles of their own, but they were less formidable than those of their comrades. As already described, they had the greatest difficulty in finding their true position amid the fog. Their action began successfully by a company of the 2nd Bedford s, together with a French company, rushing an isolated German trench and killing 70 men who occupied it. This was a small detached operation, for the front line of the advancing brigade was formed by the 19th Manchesters on the left, and by the 20th on the right, the latter in touch with the French 153rd of the line. The 19th reached the south-eastern corner of Guillemont, failed to get in touch with the Scots Fusiliers, and found both its flanks in the air. It had eventually to fall back, having lost Major Rolls, its commander, and many officers and men. The 20th Manchesters advanced upon the German Malzhorn Trenches and carried the front one, killing many of the occupants. In going forward from this point they lost 200 of their number while passing down a bullet-swept slope. Three out of four company commanders had fallen. Beyond the slope was a sunken road, and at this point a young lieutenant, Musker, found himself in command with mixed men from three battalions under his orders. Twelve runners sent back with messages were all shot, which will give some idea of the severity of the barrage. Musker showed good powers of leadership, and consolidated his position in the road, but was unfortunately killed, the command then devolving of the upon a sub-lieutenant. The Bedfords came up to reinforce, and some permanent advance was established in this quarter—all that was gained by this very sanguinary engagement, which cost about 3000 men. The Bantams lost heavily also in this action though they only played the humble role of carriers to the storming brigades.

The whole of the fighting chronicled in this chapter may be taken as an aftermath of the action of July 14, and as an endeavour upon our part to enlarge our gains and upon the part of the Germans to push us out from what we had won. The encroachment upon High Wood upon the left, the desperate defence and final clearing of Delville Wood in the centre, and the attempt to drive the Germans from Guillemont upon the right—an attempt which was brought later to a successful conclusion—are all part of one system of operations designed for the one end.

It should be remarked that during all this fighting upon the Somme continual demonstrations, amounting in some cases to small battles, occurred along the northern line to keep the Germans employed. The most serious of these occurred in the Eleventh Corps district near Fromelles, opposite the Aubers Ridge. Here the Second Australians upon the left, and the Sixty-first British Division upon the right, a unit of second-line Territorial battalions, largely from the West country, made a most gallant attack and carried the German line for a time, but were compelled, upon July 20, the day following the attack. to fall back once more, as the gun positions upon the Aubers Ridge commanded the newly-taken trenches. It was particularly hard upon the Australians, whose grip upon the German position was firm while the two brigades of the Sixty-first, though they behaved with great gallantry, had been less successful in the assault.