XI. The Gaining of the Thiepval Ridge

Assault on Thiepval by Eighteenth Division—Heavy fighting—Cooperation of Eleventh Division—Fall of Thiepval —Fall of Schwaben Redoubt—Taking of Stuff Redoubt — Important gains on the Ridge

Having treated the successful advance made by Rawlinson’s Fourth Army upon September 15, it would be well before continuing the narrative of their further efforts to return to Gough’s Army upon the north, the right Canadian wing of which had captured Courcelette, but which was occupied in the main with the advance upon the Thiepval Ridge.

The actual capture of Thiepval was an operation of such importance that it must be treated in some detail. The village, or rather the position, was a thorn in the side of the British, as it lay with its veteran garrison of Würtembergers, girdled round and flanked by formidable systems of trenches upon the extreme left of their line. Just above Thiepval was a long slope ending in a marked ridge, which was topped by the Schwaben Redoubt. Both armies recognised the extreme importance of this position, since its capture would mean a fire-command over all the German positions to the north of the Ancre, while without it the British could never reap the full result of their success in breaking the line upon July 1. For this reason, instructions had been given to the picked German troops who held it to resist at all costs, even to the death. They had massed at least four hundred guns in order to beat down every assault. Yet the attempt must be made, and it was assigned to Jacob’s Second Corps, the actual Divisions engaged being the Eighteenth and the Eleventh, both of them units recruited in the South of England. The latter was distinguished as the first English Division of the New Armies, while the former had already gained great distinction in the early days of the Somme battle when they captured Trones Wood. They were supported in their difficult venture by a considerable concentration of artillery, which included the guns of the Twenty-fifth and Forty-ninth Divisions as well as their own. Jacob, their Corps leader, was an officer who had risen from the command of an Anglo Indian Brigade to that of a Corps within two years. The whole operation, like all others in this region, was under the direction of Sir Hubert Gough.

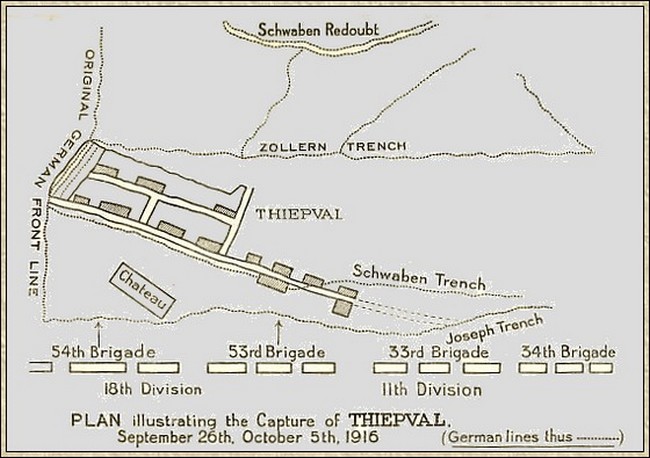

Plan illustrating the Capture of Thiepval, September 26, October 5, 1916

Every possible preparation was made for the assault, and all the requirements of prolonged warfare were used to minimise the losses and ensure the success of the storm-troops. Four tanks were brought up to co-operate, and one of them, as will be shown, was of vital use at a critical moment. Instructions were given to the advancing battalions to let their own shrapnel strike within a few yards of their toes as they advanced, huddling in a thick line behind the screen of falling bullets which beat down the machine-guns in front. With fine judgment in some cases the supports were taken out of the advanced trenches and concealed here or there so that the answering barrage of the enemy fell upon emptiness. So war-wise were the British, and so cool their dispositions, that certain of the enemy trenches were actually exempted from bombardment, so that they might form an intact nucleus of defence when the place was taken.

The Canadian Corps were to attack from Courcelette upon the right, but their advance was only indirectly concerned with Thiepval Village, being directed towards the ridge which runs north-west of Courcelette to the Schwaben Redoubt. Next to the Canadians on the left was the Eleventh Division, and on their left the Thirteenth, which had been strengthened by the addition of the 146th Brigade of the Forty-ninth Division. The latter brigade held the original British front line during the action so as to release the whole of the Eighteenth Division for the advance. The immediate objective of this division was Thiepval Village, to be followed by the Schwaben Redoubt. Those of the Eleventh Division on its right were Zollern and Stuff Redoubts.

The Eighteenth Division assaulted with two brigades, the 53rd on the right, the 54th on the left, each being confronted by a network of trenches backed by portions of the shattered village. The advance was from south to north, and at right angles to the original British trench line. The hour of fate was 12.35 in the afternoon of September 26.

The average breadth of No Man’s Land was 250 yards, which was crossed by these steady troops at a slow, plodding walk, the pace being regulated by the searching barrage, which lingered over every shell hole in front of them. Through the hard work of the sappers and Sussex pioneers, the assembly trenches had been pushed well out, otherwise the task would have been more formidable.

Following the fortunes of the 53rd Brigade upon the right, its movements were supposed to synchronise with those of the 33rd Brigade upon the left flank of the Eleventh Division. The right advanced battalion was the 8th Suffolk, with the 10th Essex upon the left, each of them in six waves. Close at their heels came the 8th Norfolk, whose task was to search dug-outs and generally to consolidate the ground won. The front line of stormers rolled over Joseph Trench, which was the German advanced position, but before they had reached it there was a strange eruption of half-dressed unarmed Germans yelling with terror and bolting through the barrage. Many of them dashed through the stolid Suffolks, who took no notice of them, but let them pass. Others lost their nerve like rabbits at a battle, and darted here and there between the lines until the shrapnel found them. It was an omen of victory that such clear signs of shaken moral should be evident so early in the day. There was sterner stuff behind, however, as our men were speedily to learn.

The advance went steadily forward, cleaning up the trenches as it went, and crossing Schwaben Trench, Zollern Trench, and Bulgar Trench, in each of which there was sharp resistance, only quelled by the immediate presence of our Lewis guns, or occasionally by the rush of a few determined men with bayonets. It was 2:30 before the advance was brought to a temporary stand by machine-gun fire from the right. After that hour a small party of Suffolks under Lieutenant Mason got forward some distance ahead, and made a strong point which they held till evening, this gallant young officer falling under the enemy’s fire.

The The success of the Suffolks upon the right was equalled by that of the Essex on the left, passing through the eastern portion of Thiepval without great loss, for the usual machine-gun fire seemed to have been stamped out by the British guns. The whole of this fine advance of the 53rd Brigade covered about 1000 yards in depth and accounted for a great number of the enemy in killed, wounded, and prisoners. The advance made and the cost paid both showed that our officers and soldiers were learning the lessons of modern warfare with that swift adaptability which Britain has shown in every phase of this terrific and prolonged test. This old, old nation’s blood has flowed into so many younger ones that her own vitality might well be exhausted; but she has, on the contrary, above all the combatants, given evidence of the supple elasticity of youth, moulding herself in an instant to every movement of the grim giant with whom she fought.

Great as had been the success of the 53rd Brigade, it was not possible for them to get on to the Schwaben Redoubt, their ultimate objective, because, as will be shown, matters were more difficult upon the left, and one corner of the village was still in German possession. They ended the day, therefore, with two battalions consolidating the Zollern Line, a third in support in the Schwaben Trench, and a fourth, the 6th Berks, bringing up munitions and food to their exhausted but victorious comrades. The front line was much mixed, but the men were in good heart, and a visit from their Brigadier in the early morning of the 27th did much to reassure them. To carry on the story of this brigade to the conclusion of the attack it may be added that the whole of the 27th was spent on consolidation and on a daring reconnaissance by a captain of the 53rd Trench Mortar Battery, who crawled forward alone, and made it clear by his report that a new concerted effort was necessary before the Brigade could advance.

We shall now return to 12.35 P.M. on September 26, and follow the 54th Brigade upon the left. The advance was carried out by the 12th Middlesex, with instructions to attack the village, and by the 11th Royal Fusiliers, whose task was to clear the maze of trenches and dug-outs upon the west of the village, while the 6th Northamptons were to be in close support. So difficult was the task, that a frontage of only 300 yards was allotted to the Brigade, so as to ensure weight of attack—the Fusiliers having a front line of one platoon.

The advance ran constantly into a network of trenches with nodal strong points which were held with resolution and could only be carried by fierce hand-to-hand fighting. Captain Thompson, Lieutenants Miall-Smith and Cornaby, and many of their Fusiliers in the leading company, were killed or wounded in this desperate business. So stern was the fight that the Fusiliers on the left got far behind their own barrage, and also behind their Middlesex comrades on the right, who swept up as far as the château before they were brought to a temporary halt. Here, at the very vital moment, one of the tanks, the only one still available, came gliding forward and put out of action the machine-guns of the château, breaking down in the effort, and remaining on the scene of its success. Across the whole front of the advance there were now a series of small conflicts at close quarters, so stubborn that the left wing of the Fusiliers was held stationary in constant combat for the rest of the day. Extraordinary initiative was shown by privates of both leading battalions when left without officers in this scattered fighting, and here, no doubt, we have a result depending upon the formed educated stuff which went to the making of such troops as these London units of the new armies. Private Edwards and Private Ryder each gained their V.C. at this stage of the action by single-handed advances which carried forward the line. Corporal Tovey lost his life in a similar gallant venture, bayoneting single-handed the crew of a machine-gun and silencing it. Fierce battles raged round garrisoned dug-outs, where no quarter was given or taken on either side. One considerable garrison refused to surrender and perished horribly in the flames of their wood-lined refuge. Those who fled from their refuges were cut down by Lewis guns, a lieutenant of the Fusiliers getting 50 in this manner. This officer also distinguished himself by his use of a captured map, which enabled him to lead his men to the central telephone installation, where 20 operators were seized by a corporal and two files of Fusiliers, who afterwards put the wires out of gear.

These great results had not been obtained without heavy losses. Colonel Carr of the Fusiliers, Major Hudson, and the Adjutant had all fallen. About three in the afternoon the village had all been cleared save the north-west corner, but the battalions were very mixed, the barrage deadly, the order of the attack out of gear, and the position still insecure. The 54th Brigade was well up with the 53rd upon the right, but upon the left it was held up as already described. The German egg bombs were falling in this area as thick as snowballs in a schoolboy battle, while the more formidable stick bombs were often to be seen, twenty at a time, in the air.

A great deal now depended upon the supports, as the front line was evidently spent and held. The immediate support was the 6th Northamptons. In moving forward it lost both Colonel Ripley and the Adjutant, and many officers fell, two companies being left entirely to the charge of the sergeants, who rose finely to their responsibilities. When by four o’clock the battalion had got up through the barrage, there were only two unwounded company officers left standing, both second lieutenants. It was one more demonstration of the fact that a modern barrage can create a zone through which it is practically impossible for unarmoured troops to move. The result was that the battalion was so weak by the time it got up, that it was less a support to others than a unit which was in need of support. The three depleted battalions simply held their line, therefore, until night, and under the cover of darkness they were all drawn off, and the remaining battalion, the 7th Bedfords, took their place. That this could be done at night in strange trenches within a few yards of the German line is a feat which soldiers will best appreciate. The result was that as day broke on the 27th the Germans were faced not by a fringe of exhausted men, but by a perfectly fresh battalion which was ready and eager for immediate attack.

The whole of Thiepval had been taken upon the 26th, save only the north-west corner, and it was upon this that two companies of the Bedfords were now directed, their objectives being defined for them by a captain who had fought over the ground the day before. Thanks to the gallant leadership of another captain and of Lieutenant Adlam (the latter gaining his Victoria Cross), the place was carried at small loss, and this last refuge of the Thiepval Germans was cleared out. It was a glorious achievement, for by it this very strong point, held against all attacks, French or British, for two years, passed permanently into our hands. The losses were not excessive for such a gain, amounting to about 1500 men. Those of the Germans were very much heavier, and included 600 prisoners drawn from four different regiments. Over 1000 dead were counted.

We will now hark back to 12.35 P.M., the hour of assault, and follow the fortunes of the Eleventh or first English Division of the New Armies which was advancing, upon the right of the Eighteenth Division. Within half an hour of the assault the 33rd Brigade and the 34th had crossed both the Joseph and the Schwaben Trenches, the 6th Borders, 9th Sherwood Foresters, 8th Northumberland Fusiliers, and 9th Lancashire Fusiliers forming the front line. Keeping some sort of touch with Maxse’s men on the left they pushed on until their right wing was held up by violent machine-gun fire from the Zollern Redoubt and from Mouquet Farm, the losses falling especially upon the 5th Dorsets. Between six and seven in the evening a mixed body of troops from the division, assisted by the machine-guns of two stranded tanks, attacked Mouquet and finally carried it.

The Eighteenth Division had still a very formidable task before it to be undertaken with the co-operation of the Eleventh upon its right. This was the capture of the formidable stronghold, made up of many trenches and called the Schwaben Redoubt. It was a thousand yards distant up a long broken slope. No time was lost in tackling this new labour, and at 1 P.M. on September 28 the troops moved forward once again, the same brigades being used, but the worn battalions being replaced by fresh units drawn from the 55th Brigade. The 53rd Brigade on the right had the undefeatable Suffolks and the 7th Queen’s Surreys in the van with Norfolks and Essex behind. The 54th upon a narrower front had the 7th Bedfords in front, with the 5th West Yorks from the Forty-ninth Division in immediate support, the Buffs and East Surrey being in Divisional Reserve. The Germans had got a captive balloon into the air, but their gunnery was not particularly improved thereby.

At the first rush the Suffolk and Queen’s on the right took Bulgar and Martin Trenches, while the Eleventh Division took Hessian. By 2:30 Market Trench had also fallen. The troops were now well up to Schwaben, and small groups of men pushed their way home in spite of a furious resistance. The Eleventh Division had won home on the right, and the Suffolks were in touch with them and with the Queen’s, so that the position before evening was thoroughly sound. Part of this enormous stronghold was still in German hands, however, and all our efforts could not give us complete control.

Upon the left the 7th Bedfords, leading the 54th Brigade, had made a very notable advance, crossing Market Trench and getting well up to the western face of the great Redoubt. The Reserves, however, lost direction amid the chaos of shell-holes and trenches, drifting away to the left. The Schwaben was occupied at several points, and the first-fruits of that commanding position were at once picked, for the light machine-guns were turned upon the German fugitives as they they rushed with bent backs down the sloping trenches which led to St. Pierre Divion. The West Yorkshires were well up, and for a time these two battalions and the Germans seem to have equally divided this portion of the trench between them. There was stark fighting everywhere with bomb and bayonet, neither side flinching, and both so mixed up that neither German nor British commanders could tell how the units lay. In such a case a General can only trust to his men, and a British General seldom trusts in vain.

As night fell in this confused scene where along the whole line the Eighteenth Division had reached its objective but had not cleared it, attempts were made to bring up new men, the Berkshires, a battalion of young drafts, relieving the Suffolks on the right. In the morning two local counter-attacks by the Germans succeeded in enlarging their area. At the same time the 55th Brigade took over the front, the four battalions being reunited under their own! Brigadier. It was clear that the German line was thickening, for it was a matter of desperate urgency to them to recover the Redoubt. They still held the northern end of the labyrinth. On September 30 the East Surreys, moving up behind a massive barrage, took it by storm, but were driven out again before they could get their roots down. The Germans, encouraged by their success, surged south again, but could make no headway. On October 1 the tide set northwards once more, and the Buffs gained some ground. From then till October 5, when the Eighteenth Division was relieved by the Thirty-ninth, there were incessant alarms and excursions, having the net result that at the latter date the whole Redoubt with the exception of one small section, afterwards taken by the Thirty-ninth, was in our hands. So ended for the moment the splendid service of the Eighteenth Division. Nearly 2000 officers and men had fallen in the Schwaben operations, apart from the 1500 paid for Thiepval. It is certain, however, that the Schwaben garrison had suffered as much, and they left 232 prisoners in the hands of the victors.

For the purpose of continuity of narrative, we have kept our attention fixed upon the Eighteenth Division, but the Eleventh Division, which we have left at Mouquet Farm some pages before, had been doing equally good work upon the right. In the afternoon of September 27 the 6th Borders, rushing suddenly from Zollern Trench, made a lodgment in Hessian Trench, to which they resolutely clung. On their left the 6th Yorks and 9th West Yorks had also advanced and gained permanent ground, winning their way into the southern edge of Stuff Redoubt. Here they had to face a desperate counter-attack, but Captain White, with a mixed party of the battalions named, held on against all odds, winning his V.C. by his extraordinary exertions. During the whole of September 29 the pressure at this point was extreme, but the divisional artillery showed itself to be extremely efficient, and covered the exhausted infantry with a most comforting barrage.

The 32nd Brigade was now brought up, and on September 30 the advance was resumed, the whole of this brigade and the 6th Lincolns and 7th South Staffords of the 33rd being strongly engaged. The results were admirable, as the whole of Hessian Trench and the south of Stuff Redoubt were occupied. That night the Eleventh Division was relieved by the Twenty-fifth, and it will now be told how the conquest of the Ridge was finally achieved. The Eleventh withdrew after having done splendid work and sustained losses of 144 officers and 3500 men. Their prisoners amounted to 30 officers and 1125 of all ranks, with a great number of machine-guns and trench mortars.

After the fall of Thiepval and the operations which immediately followed it the front British line in this quarter ran approximately east and west along the Thiepval-Courcelette ridge. As far as part of the front was concerned we had observation over the Valley of the Ancre, but in another part the Germans still held on to the Stuff Redoubt, and thence for a stretch they were still on the crest and had the observation. The Stuff Redoubt itself on the southern face had been occupied by the Eleventh, when the Schwaben Redoubt was taken by the Eighteenth Division, but the northern faces of both were still in the hands of the enemy. These had now to be taken in order to clear up the line. A further stronghold, called The Mounds, immediately to the north, came also within the operation.

The Twenty-fifth Division had, as stated, relieved the Eleventh, and this new task was handed over to it. Upon October 9 the first attack was made by the 10th Cheshires, and although their full objective was not reached, the result was satisfactory, a lodgment being made and 100 of the garrison captured, with slight casualties to the stormers, thanks to the good barrage and the workmanlike way in which they took advantage of it. A strong attempt on the part of the Germans to prevent consolidation and to throw out the intruders was quite unsuccessful.

Stuff Redoubt System, showing Hessian, Regina, and Stuff

The 8th North Lancs were now placed in the position of the Cheshires, while the Thirty-ninth Division upon the left joined in the pressure. Upon October 10 an attack was made by the 1 6th Sherwoods supported by the 17th Rifles of the 117th Brigade; but it had no success. On the 12th there was a renewed attack by units of the 118th Brigade, chiefly the 4th Black Watch. This succeeded in advancing the line for a short distance, and upon October 15 it repulsed two local counter-attacks. Upon the right the 8th North Lanes upon October 14 had a very successful advance, in which they carried with moderate loss the stretch of line opposite, as well as the position called The Mounds. Two machine-guns and 125 prisoners were taken.

The British now had observation along the whole ridge with a line of observation posts pushed out beyond the crest. There were formidable obstacles upon their right front, however, where the Regina Trench and a heavily fortified quadrilateral system lay in front of the troops already mentioned, and also of the Canadians on the Courcelette line. In order to get ready for the next advance there was some sidestepping of units, the hard- worked Eighteenth coming in on the right next the Canadians, the Twenty-fifth moving along, and the Thirty-ninth coming closer on the left. On October 8 the Canadians had a sharp action, in which the Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta, and Winnipeg Battalions showed their usual resolution, and took a couple of hundred prisoners, but were unable to gain much ground. A concerted movement of the whole line was now organised.

The great Stuff Trench, which was roughly a continuation of the Regina, was opposite the centre of the attack, and was distant some 300 yards from the British front. The barrage arrangements coordinated by the Second Corps (Jacob), to which these units now belonged, worked most admirably. The attack was made all along the line and was eminently successful. At 12.35 upon October 21 the general advance began, and at 4:30 the whole objective, including Stuff and Regina, was in the hands of the British and Canadians. It was a fine victory, with 20 machine-guns and 1000 prisoners of the 5th Ersatz and Twenty-eighth Bavarian Divisions as trophies. So rapid was the consolidation that before morning trenches were opened out between the captured line and the old British position. A curious incident in this most successful attack was that the 8th Border Regiment advanced at least a thousand yards beyond its objective, but was successful in getting back. By this brilliant little action the enemy was finally driven down upon a three-mile front north of Thiepval and Courcelette, until he had no foothold left save the marshes to the south of the Ancre, where he cowered in enfiladed trenches for that final clearing up which was only delayed by the weather. It should be added that on this same date, October 21, the left of the British line, formed by the Thirty-ninth Division, was attacked by storm-troops of the German Twenty-eighth Reserve Division, armed with Flammenwerfer and supported by 60 light batteries. The attack was formidable, and twice got into the British line, but was twice driven out again, leaving many prisoners and trophies behind. The Sussex and Hampshire troops of the 116th Brigade, aided by the 17th Rifles, stood Splendidly to their work, and ended by holding every inch of their ground, and adding a new German trench which was carried by the 14th Hants.

From this time onwards this northern section of the line was quiet save for small readjustments, until the great effort upon November 13, which brought the autumn campaign to a close with the considerable victory of Beaumont Hamel. From the point which the Second Corps had now reached it could command with its guns the Valley of the Ancre to the north of it, including some of those positions which had repulsed our attack upon July 1 and were still in German hands. So completely did we now outflank them from the south that it must have been evident to any student of the map that Haig was sure, sooner or later, to make a strong infantry advance over the ground which was so completely controlled by his artillery. It was the German appreciation of this fact which had caused their desperate efforts at successive lines of defence to hold us back from gaining complete command of the crest of the slope. It will be told in the final chapter of this volume how this command was utilised, and a bold step was taken towards rolling up the German positions from the south—a step which was so successful that it was in all probability the immediate cause of that general retirement of the whole German front which was the first great event in the campaign of 1917.